Abstract

Graduates require employability competences, such as flexibility and team working skills, to gain and maintain employment. Online learning platforms (OLPs) can provide students with resources for reflection, which is a key competence for employability. However, little is known about the design of OLPs meant to provide reflective practices that foster students’ employability competences. This research study aims to identify design principles of OLPs providing reflective practices that foster the development of employability competences. Five design principles were derived from thematic analysis following two focus group interviews with students and educational experts in this qualitative study: 1) Embed the OLP in curricular and institutional activities that foster competence development; 2) Facilitate the analysis of students’ current state regarding employability competences; 3) Provide recommendations and a repository with learning activities that help students to formulate goals and plan activities; 4) Facilitate the undertaking and recording of learning activities, supported by a blend of three forms of interaction (instructor-student; student–student or student-content); and 5) Foster reflection in and on action via opportunities for applying newly learned knowledge in different settings and reviewing activities via reflective journaling and knowledge sharing. This study is the first to conceptualise design principles for an OLP that is organised to provide reflective practices for the development of employability competences. The design principles were based on students’ and teachers’ experiences and are grounded in theory. They can inform future research as well as practitioners developing OLPs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Higher education institutions (HEIs) are putting increasing focus on the development of employability competences, alongside specific academic knowledge and skills, in order to prepare graduates for the labour market (Aarts & Künn, 2019; Bridgstock & Jackson, 2019). Since reflection is considered as a key competence for the development of employability (Clarke, 2018; Moon, 2004), higher education is increasingly embedding reflective practices that elicit reflection and, in turn, the development of students’ employability competences (Van Beveren et al., 2018).

The past decades have shown increasing use of technology within higher education to support activities associated with the acquisition of knowledge and the development of skills, including reflection (Iqbal et al., 2022; Kori et al., 2014; Lin et al., 1999). Online learning platforms (OLPs) can be beneficial for eliciting students’ reflection, because they include tools such as chats, blogs and online discussion forums that have been acclaimed as supporting reflective learning activities (Burhan-Horasanlı & Ortaçtepe, 2016; Kori et al., 2014). OLPs offer the opportunity to apply pedagogical approaches that allow the embedment of employability development into the curriculum (Harvey, 2005).

However, to the best of our knowledge, little to no attention has been paid to the design of OLPs meant to support reflective practices, incorporating potentially both curricular and extra-curricular learning activities, and fostering students’ employability competences. Since OLPs and their methods of design can differ widely, defining design principles and having insight into how they contribute to the effectiveness of an OLP is relevant (Mupinga et al., 2006). Van den Akker et al. (2006) defined design principles as heuristic guidelines to help others select and apply the most appropriate substantive and procedural knowledge for specific tasks in their own settings.

To be able to identify design principles for online learning platforms organised to provide reflective practices for developing employability competences, we first position ourselves with regard to the underlying theoretical concepts: employability, reflective practice, online learning platforms and the learner together with the broader context.

1.1 Employability

The concept of employability has been studied in different strands of the literature, mainly related to either human resource development or higher education (Scoupe et al., 2023). A competence-based approach to employability dominates in the context of higher education. It entails the identification and development of competences, including knowledge, skills and attitudes and attributes that foster students’ ability to obtain and maintain employment (Abelha et al., 2020; Bridgstock, 2009; Bridgstock & Jackson, 2019). Scoupe et al. (2023) described a multidimensional competence-based approach to employability. One of these dimensions is related to self-management or meta-cognitive competences that encompass the capacity for reflection and evaluation (Scoupe et al., 2023). The ongoing process of reflection and evaluation is addressed in the literature as key for employability (Bridgstock, 2009; Pool & Sewell, 2007). Other employability competences described by Scoupe et al. (2023) include expertise-based competences, including knowledge, skills and attitudes needed to perform in a particular field of expertise; social competences, such as networking skills and the capacity to collaborate with others; emotional regulation, that is, the ability to perceive, access and control emotions when facing new situations or challenges; efficacy beliefs that are related to the extent of a positive self-esteem; lifelong learning and flexibility, which includes the need to continue learning and to (pro-)actively as well as passively adapt to changing situations and environments; and lastly, a healthy work-life balance, the ability to balance personal and professional goals.

1.2 Reflective practice

Reflective practices are a vital element enhancing students’ learning by reflection on their experiences (Mann et al., 2007; Rogers, 2001). Based on literature about reflection (Boud et al., 1985; Moon, 2004; Rogers, 2001) and reflective practices (Atkins & Murphy, 1995; Boyd & Fales, 1983; Schön, 1983), a reflective practice that fosters employability competences can be defined as a recursive process of internally examining and exploring a sense of inner discomfort regarding employability competences, followed by a cascade of learning activities (Heymann et al., 2022). Five phases of reflective activities fit into this practice. First, students need to become aware by developing a sense of inner discomfort regarding employability competences, caused by an experience (e.g., a presentation, an internship, a peer story). The awareness of inner feelings leads to an analysis of the current state, which consists of identifying existing knowledge, collecting additional information and challenging assumptions. Typical learning activities that support this stage are self-reflection, self-assessments and feedback from peers, coaches or professionals. Next, students draft and plan a solution in terms of goal setting and personal development planning regarding the development of their employability competences. The fourth stage – take action – entails experimentation in the form of undertaking activities that yield experiences that enable re-evaluation of the original problem. These learning activities derive not only from curricular courses, but also from co-curricular and extracurricular activities. Students collect and maintain evidence of achievement of the activities undertaken and the outcomes as defined in their personal goals, noted in a portfolio. Finally, student reflect on their experience via reflection-in action – examining experiences as they happen – and reflection-on-action which involves reviewing, describing, analysing and evaluating past practices. This re-evaluation enables students to develop a new perspective on the initial situation of inner discomfort regarding their employability competences.

1.3 Online learning platforms

Online learning platforms can be effective in fostering employability competences by providing meaningful learning experiences. An online learning platform (OLP) can be defined as an environment where learning takes place moderated by technology (Oliwa, 2021). An OLP might encompass an integrated set of online tools, services and resources that support a student’s central learning experience by unifying educational theory and practice, technology and content (Hill, 2012). OLPs offer students a flexible and personalised approach to their learning process, facilitate collaboration and communication in synchronous and asynchronous modes, and create a bridge between curricular and extracurricular activities (Harvey, 2005; Kumar Basak et al., 2018; Reese, 2015). OLPs can support reflective practices via online tools such as self- and peer-assessments, reflective exercises, chats, blogs, online discussion forums, learning journals and e-portfolios (Kori et al., 2014; Lin et al., 1999; Moon, 2004).

Hollenbeck et al. (2011) identified five pedagogical design principles for OLPs. First, student-to-student interaction refers to tools, such as online discussion forums, blogs, e-mail or chats that facilitate communication between students about concepts being addressed. Second, it is important for students to have easy access to their instructor. This instructor-to-student interaction should include reciprocal communication that also supports the learner’s instruction, interventions and communications on the platform (Park & Lim, 2019). The third pedagogical principle concerns the accuracy and validity of an OLP’s content. Quality content is the extent to which the information on a website is perceived as valid and dependable (Hollenbeck et al., 2011). Fourth, the relation between the accuracy and completeness with which students achieve certain goals and the resources expended to achieve those goals is defined as goal efficiency. If functions of an OLP work properly and are easy to use, task completion time and errors are expected to be reduced, which, in turn, increases user satisfaction (Hollenbeck et al., 2011). The fifth principle, appeal, has to do with presentation, attractiveness, display consistency, categorisation of the information in a user-friendly format, customisation and flexibility. These aspects facilitate understanding and navigating through the contents of the OLP.

1.4 The learner and the broader context

To achieve the technological and pedagogical benefits associated with OLPs, it is important to gain insight into the beliefs, attitudes and behaviour that impact students’ intentions to use an OLP. Determinants of such intentions have been studied and described in two prominent theoretical models: the technology acceptance model and the decomposed theory of planned behaviour (Ahmed & Ward, 2016). Both models are grounded in the beliefs-intention-behaviour structure, wherein behavioural intention captures the influential factors that affect student’s behaviour, that is, the actual use of an OLP (Ahmed & Ward, 2016).

Motivation is considered a key determinant of learning. Motivation involves the internal processes that affect the direction and level of behaviour (Lee et al., 2005). Direction involves the selection, initiation, operationalisation and termination of the type of behaviour. Direction gives behaviour a specific purpose. The level of behaviour reflects the intensity, the strength and persistence of the behaviour concerned (Alsawaier, 2018; Buckley & Doyle, 2016; Lee et al., 2005).

Two types of behavioural drivers are distinguished in the literature: intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. According to Ryan and Deci (2000), intrinsic motivation in an educational context refers to engagement of students in learning activities for their own sake, triggered by the desire to perform a learning activity in order to know, to accomplish or to experience stimulation (Buckley & Doyle, 2016). In the case of extrinsic motivation, the stimulus to learn is always external to the learner, for example, reward or recognition or the dictates of other people (Lee et al., 2005). Individual characteristics of the learner, such as motivation, constantly interact with the broader environment in which students are studying (Virtanen & Tynjälä, 2019). For example, the influence of peers, teachers, and the culture of the school is not to be neglected (Lim & Kim, 2003).

1.5 Research question

This research study aims to identify design principles of online learning platforms that provide reflective practices fostering the development of employability competences. The research question is: What are design principles for online learning platforms meant to support reflective practices that foster the development of employability competences?

2 Methods

A qualitative exploratory-descriptive design using focus groups was adopted to elicit information about the design principles for an OLP that fosters employability competences via reflective practices. The use of focus groups enables gathering large amounts of information regarding attitudes, beliefs and experiences from different perspectives in a short period, through natural communication and stimulated group interaction (Dawson et al., 1993; Krueger & Casey, 2002). Although focus groups can be biased by social pressure to conform to the group norms, the group discussions and interactions and sharing opinions from different perspectives are recognized as better than individual interviews for exploring a complex issue in depth (Dawson et al., 1993; Krueger & Casey, 2002).

2.1 Context and sampling strategy

The focus groups were conducted at a Dutch university. Since the focus of this research study was to identify design principles for an online learning platform that fosters students’ employability competences, one focus group was conducted with a group of graduate students (n = 5), while another focus group included educational experts (n = 5).

The students were recruited from various study programs (i.e., Organizational Learning, Learning and Development, Marketing and Economics, and Psychology) via an invitational email, sent by the university’s Career Services department. The focus group with students focused on both their experiences with online learning platforms, and their preferences regarding reflective practices for the development of their employability competences.

The second focus group consisted of three teachers, two of them also assigned as coaches, and two staff members who were involved in educational innovation projects on student employability. The educational experts came from various disciplines (i.e., Education, Science and Engineering, Economics and Business). Regarding the educational experts, the interview covered questions about their expertise concerning online learning platforms as ways to provide reflective practices and how students can effectively develop employability competences.

During both focus groups, one particular online learning platform implemented at the university was referred to during the interviews, by way of example. The platform consisted of a learning management system, an online self-assessment questionnaire about employability and a portal with resources, including various online resources (e.g., personality tests, vacancies, reading materials), activities (lectures and workshops) and online career modules.

Both students and educational experts participated in the focus groups on a voluntary basis, with anonymous analysis and reporting. Before the interview started, a brief introduction was given to the participants about the procedure, the research topic, and permission was obtained for recording the interview.

2.2 Data collection methods and instruments

Prior to the interviews, a semi-structured guideline was composed, based on the theoretical frameworks as described above. The interview guideline consisted of main questions and sub-questions per theme, allowing the interviewer to examine different experiences, insights, and opinions.

The two focus groups took approximately 1 h each and were conducted via Zoom. The focus group with the students happened in English, while the interview with the educational experts was conducted in Dutch. In this paper, quotations of the educational experts have been translated. The focus groups were audio-recorded, which allowed the interviewer to maintain focus on the group rather than taking notes (Krueger & Casey, 2002).

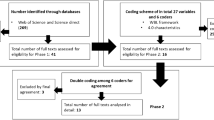

2.3 Data processing, thematic analysis and reliability

The interviews were fully transcribed, followed by upload into Atlas.ti for thematic content and co-occurrence analysis. Thematic analysis was used to identify, analyse, and report patterns within the qualitative data. Exploration of the data included measuring the prevalence of single items or themes within or across the focus groups (Braun & Clarke, 2006). In addition, the number of instances of two codes co-occurring in the data was also determined. The more co-occurrences exist in the data, the more likely it is that a relationship exists between two concepts or themes (Friese, 2019).

The coding was done on the meaningful segments of both interviews, both deductively, starting with key concepts from literature, and inductively, by adding new themes derived from segments that could not be coded with the existing set of codes. The researcher compared new codes with the literature and either assigned the codes to existing themes or defined a new theme. Each meaningful segment could get one or more codes assigned. According to Morgan (2022) deductive thematic analysis is mostly aimed at gathering evidence related to the themes, which are often predetermined, whereas inductive analysis is focussed on identifying patterns in the data that often represent the opinions as raised by the participants of the focus groups.

This circular process of coding evolved into a codebook with deductive codes from the literature and inductive codes based on the data. The inductive codes were linked with existing themes or considered as belonging to new themes.

To determine the consistency in classifying items into mutually exclusive categories, interrater reliability was established, using Cohen’s kappa (O’Connor & Joffe, 2020). An independent coder identified codes for randomly selected meaningful segments making up 15% of the data. Differences were discussed until consensus was reached and revisions, where needed, were made. This process resulted in adequate inter-coder reliability as shown by a Cohen’s kappa of 0.723, indicating acceptable, substantial agreement between the coders (Sun, 2011).

Lastly, ATLAS.ti was used to generate reports by calculating the prevalence of and co-occurrences between the codes (Friese, 2019).

3 Results

In this section, we first present the coding scheme derived from the focus group interviews. Next, we describe the general findings regarding design principles for an OLP providing reflective practices based on the prevalence of themes (i.e., employability, reflective practice, online learning platform, and the learner and the broader context), followed by the interpretation based on co-occurrences. As previously stated, co-occurrences represent possible relations between codes or concepts. As the research question is about identifying the design principles for an OLP providing reflective practice, co-occurrences between identified themes related to the OLP (i.e., employability, features of the OLP, the learner and the context) and the phases of reflective practice (i.e., become aware, analyse current state, draft and plan a solution, take action, reflect in/on action) were investigated.

3.1 Coding scheme

The deductive and inductive codes for the focus group interviews are depicted in Table 1, including the frequencies of occurrence of each code during the two focus groups. The deductive codes represent evidence for the themes we predetermined from the literature, whereas the inductive codes represent patterns in data that were derived from the opinions of the focus group participants.

3.2 Key findings per theme

Based on the code frequencies shown in Table 1, we can derive the following key findings per theme.

3.2.1 Employability

Interviewees in both focus groups provided examples of employability competencies such as adaptability, oral and written communication, presenting, collaboration, critical strategic planning, leadership skills and networking. For students, it was important to gain more insights and feel more confident:

I would be interested in more something like a training on specific skills. Like public speaking or critical strategic planning. These kinds of things, so that I can really get in depth and then I feel like I would also be more confident communicating it at an interview. Like, I can do this because I have been trained in this. (2:54 Student A)

I directly think about presenting, public speaking and networking. I think those are three really important capabilities within a lot of jobs. (2:88 Student B)

3.2.2 Reflective practice

For students, the ‘Become aware’ phase often started with feelings of fear or uncertainty regarding a situation or their future:

A lot of people fear something or are uncertain about a situation and I think helping us with that, like that helps with changing but it also helps in more global ways with us in our personal life and work life. (2:92 Student B)

Educational experts envisioned that, by linking intended learning outcomes in curricula with employability competences, students can monitor their progress regarding the development of employability competences, which will make them more aware of their employability.

Both students and educational experts recommended an online self-assessment as a starting point for analysing students’ strengths and weaknesses. According to the students, the OLP should include an easy to search and filter overview of activities that are related both to results of the self-assessment and to other relevant activities offered within the university or linked to external resources. Such a repository filled with activities supports students in defining goals and planning activities, which aligns with the ‘Draft and plan solution’ phase. The educational experts underlined the need to define goals with a longer-term perspective in mind that overarches multiple courses or modules within a study programme.

It should actually be something they can carry with them across several subjects or at least be able to continue to focus. So it definitely has to have that kind of longitudinal approach as well. (3:152 Educational expert D)

When asked about the kinds of ‘Take action’ activities that should be available via the OLP, students suggested e-modules, online workshops, links to vacancy boards and company pages, podcasts and a functionality for registration for on-site workshops.

According to the students, reflection-in-action involves practicing knowledge and skills in different settings, whereas reflection-on-action entails asking for feedback and integrating new insights into existing knowledge. In contrast to the students, the educational experts believed that reflection-in-action involves the exchange of experiences between students.

3.2.3 Online learning platform

Regarding the features of an OLP, both students and educational experts discussed three forms of interaction: student-to-student, instructor-to-student and student-to-content interaction. The last, student-to-content interaction, was mentioned most often and has been identified as an inductive theme. Examples of content mentioned by the interviewees were podcasts, videos, self-assessments, games, links to external resources and online tutorials and articles. Students preferred to read theoretical knowledge regarding the development of employability competences. This theoretical information could be presented either as in-depth material that is linked with a curricular course or as preparatory material followed by learning activities to bring theory into practice. One student said the following about this form of blended learning:

I had the experience that we had a workshop on team building. Before that workshop, we were supposed to read some parts from the OLP on conflict resolution. And I found that a very good balance because then we got the knowledge online, but I think for especially for developing social skills, you really need to actually interact with people. (2:57 Student A)

The educational experts also discussed instructor-to-student interaction, such as moderating chats and discussion forums or posting announcements. Regarding student-to-student interaction, educational experts mentioned sharing experiences or interacting with students from other study programmes as examples of this type of interaction.

Three additional features of the OLP were mentioned by the interviewees. First was goal efficiency, meaning that the OLP should foster the development of employability competences in such a way that it allows students to gain a more in-depth understanding without putting too much effort or time to find the right and relevant activities or making them feel overwhelmed. Quality of content, which students considered to refer to content that is linked to external resources, was expected to contribute to a higher level of perceived usefulness of the OLP. Third, students also considered the appeal and interface of the OLP to be important. Presenting information in a user-friendly format was expected to help students understand and navigate through the content on the OLP.

3.2.4 Learner and context

Students mentioned several contextual factors that affect their attitude towards the use of the OLP: (1) communication and information about the existence of the OLP, (2) the OLP’s connection with curricular courses, other platforms (such as vacancy listings) and external resources, (3) follow-up provided by the OLP after undertaking activities, (4) influence from peers and instructors and (5) user-friendly categorised and searchable information.

Regarding motivation to use the OLP as a way to engage in reflective practice, students realised that they must work on their competences for themselves. However, they were also searching for motivational factors that would make them use the OLP. The use of certificates or credits and gamification were mentioned as examples of such stimuli. The educational experts mentioned the role of a coach or mentor as a motivational factor, but they also discussed the balance between supporting versus pampering students:

I think that you can organize that personal contact in a way that emphasizes the student's own responsibility and wherein a student also feels the consequences if he or she did not. I think that is also an important function of the university that you sometimes don't do things or fail and that you then learn to deal with it. You shouldn't take that away as a coach. (3:126 Educational expert C)

Two inductive topics emerged in particular from the experts’ focus group. The educational experts argued that integration of the OLP for employability with coaching or mentoring trajectories is indispensable to make students aware of their employability. They also advocated that embedding an employability competence framework in curricula is needed to ensure awareness and reflection amongst students when using an OLP for employability competence development.

Embedding employability competences in the curriculum should of course be programmatic, right? That there is a plan behind it: from where do we start? How do we build up the retention of competences? Where do different aspects of competences come from? Where do they get a place? Are there additional activities? We have company visits in our master program where you can immediately take a look at: What do our alumni do? And how does that work? That you get a concrete picture. Those are small things, yes, but they do help to paint a clear picture of where I am going as a student. (3:141 Educational expert C)

Finally, educational experts also recommended paying attention to teacher professional development when implementing an OLP that fosters the development of employability competences. This was the last inductive code, we derived from the focus groups.

When it comes to organizing your education, you may have to look much more at professional tasks as well … so you will also have to do a lot for the teaching staff to include them in the change. Yes, it is essential to also renew didactic training about employability for teachers. (3:115 Educational expert E)

3.3 Themes in co-occurrence with reflective practice

Since our aim is to identify the design principles for an OLP providing reflective practice, we present the findings from the co-occurrences tables per phase of reflective practice, as outlined in the sections below. Table 2 shows the co-occurrences of the themes employability, the features of an OLP, the learner and contextual factors with the phases of reflective practice for the students’ focus group interview, and Table 3 for the interview with the educational experts.

The students mentioned the ‘Take action’ phase of the reflective practice most often in combination with the other themes, while the educational experts discussed the first phase, ‘Become aware’, most often in combination with other themes. In both focus groups, student-to-content interaction was most frequently mentioned with respect to all phases of reflective practice.

3.3.1 Become aware

The first phase, ‘Become aware’, was mainly mentioned in combination with employability competences (students) and embedding the concept of employability in curricula (experts). Educational experts argued that the development of competences within curricula should be made more explicit to students in order to raise their awareness about their employability. As one of the experts explained:

There are 2 things that I would recommend. Firstly, that it is much clearer to students in their curriculum which intended learning outcomes are linked to employability so that they are more aware of this. And the second is that students can accomplish learning activities, such as assessments and participation. If these learning activities are aligned to these learning outcomes, they can also be linked to employability competencies so you will be able to see some kind of progression throughout the study programme. (3:171 Educational expert B)

In addition, instructor-to-student interaction, such as having a chat with a coach or mentor, can be used as an instrument to motivate students’ thinking about their employability, thus raising their awareness as well. Finally, student-to-content interaction might also induce awareness about employability. One educational expert provided the following example:

At the start of the academic year, we ask students to search for two or three vacancies on the online vacancy board. When they analyse these vacancies, they will discover that employers ask for all kinds of competences next to academic knowledge. Reading these vacancies fosters students’ awareness about their employability. (3:163 Educational expert D)

3.3.2 Analyse current state

Students mentioned ‘Analysing the current state’ mainly in combination with features of the OLP that are related to goal efficiency and student-to-content interaction. Students considered the OLP attractive to use if results of an online self-assessment could be linked with not-too-obvious suggestions for improvement of competences.

I actually thought it was a smart idea like when you get the results [following the self-assessment] and you think, “Oh, that's kind of obvious,” but you can click through on them and then it's gets more complicated. Like now you know this, you can approve or improve this and this. I think for me, that would make it more interesting. (2:86 Student B)

The educational experts linked this phase of reflective practice with learners’ motivation and contextual factors. Linking the results of the self-assessment with an overview of in-depth activities was deemed to be crucial as a follow-up to get students motivated to reflect on their current state and move forward in their development. Both students and educational experts argued that discussing the results of the self-assessment with a coach, mentor or career advisor can facilitate analysis of one’s current state.

3.3.3 Draft and plan a solution

For the next phase, ‘Draft and plan a solution’, interviewees combined this with mentions of features of the OLP such as quality of content, goal efficiency and different types of interaction.

According to the students, the OLP should foster the development of employability competences in a way that allows them to gain more in-depth understanding without putting in too much effort or time finding the right and relevant activities or making them feel overwhelmed. Information organized in a user-friendly format helps students understand and navigate through the content on the OLP. Students also preferred to get new directions for other related activities once they have finished activities that they are currently working on or completed in the past. The following conversation captures these views:

... if I would like to develop e.g. my networking skills then I would like to see something in the front of me like that “do this to develop your networking” and then if I did that, then the OLP says like “OK now you have your network in place, do this or this to make use of it.” (2:98 Student B)

In addition, students also mentioned motivational aspects together with this phase. Students mentioned that their attitude towards using the OLP in this stage of reflective practice would depend strongly on the ease of finding relevant activities that fit with their goals and with their current course-related learning activities.

…if they could, this [connecting your goals to what you are already studying] would be great. Cause then you can really link what you are studying to which competencies you would like to further develop. (2:138 Student E)

3.3.4 Take action

In the interview with students, the ‘Take action’ reflective phase was mentioned in combination with six other codes. First, students linked it with the development of employability competencies, such as adaptability, oral communication, critical strategic planning or networking to undertaking activities within the OLP. Second, students argued that experiential activities with a blended instructional design, such as reading theoretical background information on the OLP or listening to podcasts, and conducting practical exercises during workshops on-site, would fit well in an OLP. Third, students specifically mentioned student-to-content interactions that are relevant for undertaking activities. In particular, they mentioned links to external resources such as vacancy listings or external trainings offered via LinkedIn. Fourth, perceived usefulness and social influence were frequently mentioned as factors that would affect the use of the OLP when talking about undertaking activities via the OLP:

If I would hear from friends what they saw on the OLP and they are using it, I would be also more interested to use it this. So, I think that social influence from your friends is an option that might work. (2:139 Student B)

Fifth, practicing skills together, sharing experiences or interacting with students from other study programmes were brought up as forms of student-to-student interaction in combination with ‘Take action’. Lastly, regarding motivation, students mentioned certificates or other forms of evidence that they have undertaken specific activities, which they can add to any kind of portfolio or to their LinkedIn profiles. Gamification was also mentioned by two students as a motivational tool.

Educational experts mostly mentioned forms of interaction within the OLP in combination with the ‘Take action’ phase. Regarding instructor-to-student interaction, educational experts mentioned having a chat with a teacher or coach, moderating a discussion board or posting announcements. Regarding student-to-student interaction, educational experts mentioned practicing skills together, sharing experiences or interacting with students from other study programmes. The educational experts also discussed the use of an e-portfolio as a form of student-to-content interaction.

3.3.5 Reflect in and on action

The last phase of reflective practice, ‘Reflect in/on action’, was mostly mentioned in combination with features of the OLP and learner factors. For students, the OLP could help them to apply newly learned knowledge or skills in different settings. In addition, they mentioned giving and receiving feedback as a mean to reflect on action. A coach or mentor could serve as someone who keeps the student accountable regarding their competence development.

One of the educational experts suggested that the OLP should facilitate ongoing interaction between students as a follow-up to activities such as workshops. This could support the collaborative learning that fosters reflection in and on action.

Educational experts also argued that the OLP could nudge students to reflect on their actions:

That with the help of the input from the OLP students are supported in thinking about how their competence has actually developed during the course: ‘Have I become stronger at this. Do I feel something is missing? That you are a bit nudged by the OLP asking for feedback in your environment. (3:555 Educational expert D)

4 Discussion

Considering the key role of reflection in the development of employability competences and the increasing use of technology that supports learning activities, we aimed to identify how online learning platforms can be used to provide reflective practices that foster the development of employability skills of students in higher education. In the introduction, we framed reflective practice as a recurrent process that consists of five phases involving undertaking learning activities that foster the development of employability competences. In the next section, we formulate for each reflective practice phase the design principles for an OLP that are derived from the thematic analysis of the focus group interviews.

4.1 Design principles for an OLP providing reflective practice

4.1.1 Become aware

Students and educational experts both argued that an OLP cannot trigger awareness regarding the need for developing employability competences by itself. Such an OLP should be connected with curricular learning activities, with additional external content, such as vacancy listings or company pages, and preferably with coaching or mentoring trajectories organised by the school. This inductively derived observation is in line with several other studies that have advocated embedding employability in the curriculum, for example, by identifying programme objectives as employability skills, offering career development activities at the central level, and the implementation of coaching trajectories (Abelha et al., 2020; Bridgstock & Jackson, 2019; Harvey, 2005; Krouwel et al., 2019).

Therefore, we formulate the following design principle to support the first reflective practice phase ‘Become aware’:

Design principle 1

The use of an OLP organised to provide reflective practices should be triggered by curricular and institutional learning activities that foster the development of employability competences, including coaching or mentoring trajectories.

4.1.2 Analyse current state

Self-assessment fosters reflection on one’s own learning process, and helps students to evaluate their current strengths and weaknesses (Boud et al., 1985; Samuels & Betts, 2007). Self-assessment also encourages students to engage in further information-seeking activities related to goal setting (Griffiths et al., 2018).

In both focus groups, the use of online self-assessment was mentioned as an instrument to initiate self-reflection, which in turn, leads to better understanding of students’ levels of competence, as was also proposed by Martínez-Villagrasa et al. (2020). For the reflective practice phase ‘Analyse current state’, we propose the following design principle:

Design principle 2

An OLP organised to provide reflective practices facilitates online self-assessments and supports activities for gathering feedback from peers or staff to help students analyse their strengths and weaknesses in regard to their employability competences. The results of these self-assessment activities should be presented in a way that enables students to reflect on their current state.

4.1.3 Draft and plan a solution

Results of online assessments and feedback gathering should be accompanied with recommendations that help students to formulate goals in response. Goal setting is a learning activity that helps students to define realistic and measurable goals and select activities that support these goals (Jackson, 2015). Typical online learning activities that fit with this phase are blogs, wikis, media resources, and journals (Dabbagh & Kitsantas, 2012), supported by a repository that offers a comprehensive overview of all types of curricular and extra-curricular activities that foster the development of employability competences (Kleinberger et al., 2001). Information should be organised in a user-friendly format that is easily searchable and filterable, allowing students to find and select activities in an efficient manner (Hollenbeck et al., 2011). From the focus group interviews, we derived the third design principle:

Design principle 3

An OLP organised to provide reflective practices gives recommendations derived from the self-assessments and feedback gathering. In addition, the OLP includes an easily searchable and filterable repository with learning activities that help students to formulate goals and plan activities.

4.1.4 Take action

Taking action requires experimentation in the form of undertaking activities that yield experiences to use in re-evaluation of the original problem (Dewey, 1933; Schön, 1983). Interviewees in both groups (students and educational experts) suggested that the OLP should offer the following activities regarding ‘Take action’: e-modules, online workshops, links to vacancy listings and company pages, podcasts, discussion boards and a functionality for registration for on-site workshops.

Students expressed their preference regarding the use of blended learning activities for the development of their competences. Blended learning can be framed as the integration of face-to-face learning experiences with online learning experiences, with the goal of stimulating and supporting learning (Garrison & Kanuka, 2004). Both students and educational experts discussed some key challenges for blended learning activities, as also described by Boelens et al. (2017): flexibility (time, place, path and pace of learning); facilitation of students’ learning process (finding the right balance of self-regulation versus support), fostering a motivating learning climate (e.g., influence of a coach or mentor, certificates or gamification), and interaction between instructor and students (e.g., chats, moderating discussion boards or posting announcements).

These key challenges also touch upon another crucial aspect of the educational process: the role of interaction. Whereas Hollenbeck et al. (2011) described instructor-student and student–student interaction, we encountered a third form of interaction, interaction between student and content, in the thematic analysis of the focus group interviews. In the context of the OLP in our study, these three types of interaction have different functions. Both students and educational experts mentioned practicing skills together, sharing experiences or interacting with students from other study programmes as examples of student-to-student interaction, which is thought to foster the capacity to participate effectively in teams and to demonstrate communication skills (Anderson, 2003). The key element in instructor-to-student interaction is support. Such interaction is essential to stimulate critical reflection (Anderson & Garrison, 1998) and it benefits motivation and feedback (Anderson, 2003). According to the students, a coach or mentor could serve as someone who keeps the student accountable regarding their competence development by providing feedback. This was in line with the view of the educational experts, who stated that interaction with a coach or mentor is essential throughout the different stages of reflective practice. Similarly, student-to-content interaction, for example, as offered within assessments, quizzes, simulations or games, can not only help students to apply theoretical knowledge and practice skills, but can also include feedback that informs students about their progress (Kasch et al., 2021).

Design principle 4

In order to gain new experiences, an OLP organised to provide reflective practices facilitates the undertaking and recording of a broad variety of learning activities that are related to both curricular courses and extra-curricular opportunities. These opportunities are supported by a blend of three forms of interaction (instructor-student, student-student, and student-content), in both online and offline settings.

4.1.5 Reflect in and on action

By applying newly learned knowledge or skills in different settings, students reflect in action, whereas reflection on action involves reviewing and evaluating past practices (Schön, 1983). This process results into new insights and perspectives regarding the initial situation of inner discomfort with respect to employability (Mezirow, 1981). Reflective journaling by means of e-mail, blogs, e-portfolios or participation in peer discussion forums can be supportive to reflection (Lai & Land, 2009). Knowledge sharing in the form of reviewing of activities by students through the sharing of experiences promotes collaboration and reflection (Charband & Jafari Navimipour, 2016; Dabbagh & Kitsantas, 2012). These studies support the view that the OLP should facilitate ongoing interaction between students after activities such as workshops.

Design principle 5

To foster reflection in and on action, an OLP organised to provide reflective practices facilitates opportunities for applying newly learned knowledge or skills in different settings and reviewing activities via reflective journaling and knowledge sharing.

4.2 Implications for practitioners

The findings inform practitioners by providing a kind of checklist that can be used when designing and implementing such OLPs.

4.2.1 Teacher professional development

In this study, we derived inductively from the experts’ opinions that embedding the development of employability competences into the curriculum and using an OLP that provides reflective practices also requires awareness among teachers about their own teaching skills. This observation implies that embedding employability skills and competences in the curriculum requires teachers to rethink their approach to the curriculum and its courses (Fallows, 2000). Good learning and employability intentions need to be supported by learning, teaching and assessment approaches that are consistent with curricular intentions (Abelha et al., 2020; Yorke & Knight, 2006).

4.2.2 Students’ action-oriented view vs. educational experts’ valuing of awareness and analysis of the current state

The results of this study suggested that students appeared to be more action-oriented with regard to reflective practice, whereas the educational experts paid more attention to awareness and analysing the current state. This orientation seems to fit with the role of the stakeholders concerned. Providing students with opportunities to gain experiences and to evaluate and to reflect on learning activities in the past is key for developing employability competences (Moon, 2004; Pool & Sewell, 2007). The teacher’s role can be related to seminal work by Dewey (1933), who stated that appropriate guidance consists of the teacher’s ability to provoke the mind of the learner by asking questions. In the context of technology for learning, Molin (2017) summarized three teacher roles: 1) the expert guide who helps students make connections with the learning goals, 2) the facilitator of pedagogical approaches fostering reflection and feedback and 3) the connector who helps students to understand the relevance of acquired knowledge beyond the classroom.

This observation does not necessarily mean that students are not aware. However, in the end, actions count more for students. A lesson might be for the coach to be aware to check on the ‘why’ (and less on the ‘what’), even if the ‘what’ is there, to be sure that actions are motivated.

4.3 Limitations and suggestions for further research

The design principles described in this study are grounded in both theory and the experiences of students and staff, and provide a framework for future research studying OLPs, their features and outcomes. The outcome of our thematic analysis was in line with and did gather evidence supporting the themes we defined a priori from the literature (Morgan, 2022). Moreover, two themes, “Online learning platform” and “Learner & Context”, were enriched inductively with the opinions from our participants. Future research may help to elaborate, confirm or reject them.

The current study was limited to a relatively small sample that covered two perspectives, a student and an educational expert perspective. According to (Krueger, 2014), a focus group consisting of four to six participants is easier to recruit and is more comfortable for participants, but offers less experiences compared to focus groups with more participants. Hennink and Kaiser (2022) argue that the number of focus groups is more relevant for reaching saturation in qualitative research than the number of participants per group. As this study focuses on a competence-based approach to employability, we did not include perspectives from other fields of expertise, such as employers of alumni or a more technically oriented view. Future research should expand the number of focus groups for students and educational experts and include focus groups for other perspectives as well, as they might result in additional insights regarding the design of an OLP that fosters employability competences.

In our study, the interviewees were recruited within one university, located in a western-European country that provides mainly campus-based education. During the interviews, participants had one particular platform in mind. Although using a particular example of an OLP has the benefit of bringing up more concrete thoughts during the focus group sessions, it also raises the question to what extent the design principles will apply to other higher education settings, such as fully remote, online universities, or hybrid forms of learning activities, and to other geographical areas with different cultural backgrounds. We suggest that future research aim at replication of the findings for different educational and cultural settings.

As we propagate three forms of interaction according to our fourth design principle, we suggest that future research addresses trustworthiness as a relevant factor for establishing a safe and reliable learning environment for students (Anwar, 2021). Trustworthiness can be evaluated based on factors such as the credibility and reliability of both users of the OLP (Alkhamees et al., 2021) as well as the information provided on the OLP (Hollenbeck et al., 2011), and to what degree the OLP (i.e. the concerning university) conforms to the latest security and privacy standards (e.g. the EU General Data Protection Regulation).

In the present study, focus group interviews revolved around the expected and perceived value of an OLP that fosters the development of employability competences. We did not quantify the actual use and value of such an OLP. Therefore, we suggest that future research includes a more quantitatively based approach, measuring the actual use and usability of OLPs. Quantitative data could be gathered via measuring the actual usage of the OLP, and via the use of existing validated questionnaires on reflective practice (Priddis & Rogers, 2018), reflection levels (Kember et al., 2000) and the usability or perceived value of an OLP (Ahmed & Ward, 2016), or via new, yet-to-be validated questionnaires.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aarts, B., & Künn, A. (2019). Employability: the employers’ perspective: Using a stated-preferences experiment to gain insights into employers’ preferences for specific competencies. ROA, ROA Reports No. 006. https://doi.org/10.26481/umarep.2019006

Abelha, M., Fernandes, S., Mesquita, D., Seabra, F., & Ferreira-Oliveira, A. T. (2020). Graduate employability and competence development in higher education — A systematic literature review using PRISMA. Sustainability, 12(15), 5900.

Ahmed, E., & Ward, R. (2016). A comparison of competing technology acceptance models to explore personal, academic and professional portfolio acceptance behaviour. Journal of Computers in Education, 3(2), 169–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-016-0058-1

Alkhamees, M., Alsaleem, S., Al-Qurishi, M., Al-Rubaian, M., & Hussain, A. (2021). User trustworthiness in online social networks: A systematic review. Applied Soft Computing, 103, 107159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2021.107159

Alsawaier, R. S. (2018). The effect of gamification on motivation and engagement. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 35(1), 56–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-02-2017-0009

Anderson, T. (2003). Modes of interaction in distance education: Recent developments and research questions. In M. G. Moore & W. G. Anderson (Eds.), Handbook of distance education (pp. 129–144). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Anderson, T., & Garrison, D. R. (1998). Learning in a networked world: New roles and responsibilties. In C. Gibson (Ed.), Distance learners in higher education: Institutional responses for quality outcomes (pp. 97–112). Atwood.

Anwar, M. (2021). Supporting privacy, trust, and personalization in online learning. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 31(4), 769–783. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-020-00216-0

Atkins, S., & Murphy, K. (1995). Reflective practice. Nursing Standard, 9(45), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.9.45.31.s34

Boelens, R., De Wever, B., & Voet, M. (2017). Four key challenges to the design of blended learning: A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review, 22, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.06.001

Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (1985). Reflection, turning experience into learning. Routledge.

Boyd, E. M., & Fales, A. W. (1983). Reflective learning: Key to learning from experience. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 23(2), 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167883232011

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Bridgstock, R. (2009). The graduate attributes we’ve overlooked: Enhancing graduate employability through career management skills. Higher Education Research & Development, 28(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360802444347

Bridgstock, R., & Jackson, D. (2019). Strategic institutional approaches to graduate employability: Navigating meanings, measurements and what really matters. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 41(5), 468–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2019.1646378

Buckley, P., & Doyle, E. (2016). Gamification and student motivation. Interactive Learning Environments, 24(6), 1162–1175. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2014.964263

Burhan-Horasanlı, E., & Ortaçtepe, D. (2016). Reflective practice-oriented online discussions: A study on EFL teachers’ reflection-on, in and for-action. Teaching and Teacher Education, 59, 372–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.07.002

Charband, Y., & JafariNavimipour, N. (2016). Online knowledge sharing mechanisms: A systematic review of the state of the art literature and recommendations for future research. Information Systems Frontiers, 18(6), 1131–1151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-016-9628-z

Clarke, M. (2018). Rethinking graduate employability: The role of capital, individual attributes and context. Studies in Higher Education, 43(11), 1923–1937. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1294152

Dabbagh, N., & Kitsantas, A. (2012). Personal Learning Environments, social media, and self-regulated learning: A natural formula for connecting formal and informal learning. The Internet and Higher Education, 15(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.06.002

Dawson, S., Manderson, L., & Tallo, V. L. (1993). A manual for the use of focus groups. International Nutrition Foundation for Developing Countries.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think. Heath.

Fallows, S. (2000). Building employability skills into the higher education curriculum: A university‐wide initiative. Education + Training, 42(2), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910010331620

Friese, S. (2019). Qualitative data analysis with ATLAS.ti. Sage.

Garrison, D. R., & Kanuka, H. (2004). Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 7(2), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2004.02.001

Griffiths, D. A., Inman, M., Rojas, H., & Williams, K. (2018). Transitioning student identity and sense of place: Future possibilities for assessment and development of student employability skills. Studies in Higher Education, 43(5), 891–913. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1439719

Harvey, L. (2005). Embedding and integrating employability. New Directions for Institutional Research, 2005(128), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/ir.160

Hennink, M., & Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

Heymann, P., Bastiaens, E., Jansen, A., van Rosmalen, P., & Beausaert, S. (2022). A conceptual model of students' reflective practice for the development of employability competences, supported by an online learning platform. Education + Training, 64(3), 380–397. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-05-2021-0161

Hill, P. (2012, May 4). What is a learning platform? Retrieved 20 April 2021 from http://mfeldstein.com/what-is-a-learning-platform/

Hollenbeck, C. R., Mason, C. H., & Song, J. H. (2011). Enhancing student learning in marketing courses: An exploration of fundamental principles for website platforms. Journal of Marketing Education, 33(2), 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475311410850

Iqbal, M., Fredheim, L. J., Olstad, H. A., Abbas, A., & Petersen, S. A. (2022). Graduate employability skills development through reflection and self-assessment using a mobile app. In International Conference e-Society and Mobile Learning Proceedings. IADIS Press.

Jackson, D. (2015). Employability skill development in work-integrated learning: Barriers and best practice. Studies in Higher Education, 40(2), 350–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.842221

Kasch, J., Van Rosmalen, P., & Kalz, M. (2021). Educational scalability in MOOCs: Analysing instructional designs to find best practices. Computers & Education, 161, 104054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104054

Kember, D., Leung, D. Y. P., Jones, A., Loke, A. Y., McKay, J., Sinclair, K., . . . Yeung, E. (2000). Development of a questionnaire to measure the level of reflective thinking. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 25(4), 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/713611442

Kleinberger, T., Schrepfer, L., Holzinger, A., & Müller, P. (2001). A multimedia repository for online educational content In: EdMedia+ Innovate Learning (pp. 975–980). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE), Norfolk, VA. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/8710

Kori, K., Pedaste, M., Leijen, Ä., & Mäeots, M. (2014). Supporting reflection in technology-enhanced learning. Educational Research Review, 11, 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.11.003

Krouwel, S. J. C., van Luijn, A., & Zweekhorst Marjolein, B. (2019). Developing a processual employability model to provide education for career self-management. Education + Training, 62(2), 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-10-2018-0227

Krueger, R. A. (2014). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (Fifth Edition ed.). Sage Publications.

Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2002). Designing and conducting focus group interviews. In Social Analysis - Selected Tools and Techniques (vol. 18, pp. 4–23). St Paul, Minnesota, USA

Kumar Basak, S., Wotto, M., & Bélanger, P. (2018). E-learning, M-learning and D-learning: Conceptual definition and comparative analysis. E-Learning and Digital Media, 15(4), 191–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753018785180

Lai, T.-L., & Land, S. M. (2009). Supporting reflection in online learning environments. In M. Orey, V. J. McClendon, & R. M. Branch (Eds.), Educational media and technology yearbook (pp. 141–154). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-09675-9_9

Lee, M. K. O., Cheung, C. M. K., & Chen, Z. (2005). Acceptance of Internet-based learning medium: The role of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. Information & Management, 42(8), 1095–1104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2003.10.007

Lim, D. H., & Kim, H. (2003). Motivation and learner characteristics affecting online learning and learning application. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 31(4), 423–439.

Lin, X., Hmelo, C., Kinzer, C. K., & Secules, T. J. (1999). Designing technology to support reflection. Educational Technology Research and Development, 47(3), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02299633

Mann, K., Gordon, J., & MacLeod, A. (2007). Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: A systematic review. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 14(4), 595–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2

Martínez-Villagrasa, B., Esparza, D., Llacer, T., & Cortiñas, S. (2020, September 10–11). Methodology for the analysis and self-reflection of design students about their competences. Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education (E&PDE 2020). VIA University.

Mezirow, J. (1981). A critical theory of adult learning and education. Adult Education, 32(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/074171368103200101

Molin, G. (2017). The role of the teacher in game-based learning: A review and outlook. In M. Ma & A. Oikonomou (Eds.), Serious games and edutainment applications : Volume II (pp. 649–674). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51645-5_28

Moon, J. A. (2004). Reflection and employability. Learning and Teaching Support Network.

Morgan, H. (2022). Understanding thematic analysis and the debates involving its use. The Qualitative Report, 27(10), 2079–2090.

Mupinga, D. M., Nora, R. T., & Yaw, D. C. (2006). The learning styles, expectations, and needs of online students. College Teaching, 54(1), 185–189. https://doi.org/10.3200/CTCH.54.1.185-189

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220

Oliwa, R. (2021). The process of designing the functionalities of an online learning platform: A case study. Teaching English with Technology, 21(3), 101–120.

Park, T., & Lim, C. (2019). Design principles for improving emotional affordances in an online learning environment. Asia Pacific Education Review, 20(1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-018-9560-7

Pool, L. D., & Sewell, P. (2007). The key to employability: Developing a practical model of graduate employability. Education + Training, 49(4), 277–289. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910710754435

Priddis, L., & Rogers, S. L. (2018). Development of the reflective practice questionnaire: Preliminary findings. Reflective Practice, 19(1), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2017.1379384

Reese, S. A. (2015). Online learning environments in higher education: Connectivism vs. dissociation. Education and Information Technologies, 20(3), 579–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-013-9303-7

Rogers, R. R. (2001). Reflection in higher education: A concept analysis. Innovative Higher Education, 26(1), 37–57.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Samuels, M., & Betts, J. (2007). Crossing the threshold from description to deconstruction and reconstruction: Using self-assessment to deepen reflection. Reflective Practice, 8(2), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940701289410

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Ashgate Publishing Limited. citeulike-article-id:8503000.

Scoupe, R., Römgens, I., & Beausaert, S. (2023). The development and validation of the student's employability competences questionnaire (SECQ). Education + Training, 65(1), 88–105. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-12-2020-0379

Sun, S. (2011). Meta-analysis of Cohen’s kappa. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology, 11(3), 145–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10742-011-0077-3

Van Beveren, L., Roets, G., Buysse, A., & Rutten, K. (2018). We all reflect, but why? A systematic review of the purposes of reflection in higher education in social and behavioral sciences. Educational Research Review, 24, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.01.002

Van den Akker, J., Gravemeijer, K., McKenney, S., & Nieveen, N. (2006). Educational design research. Routledge.

Virtanen, A., & Tynjälä, P. (2019). Factors explaining the learning of generic skills: A study of university students’ experiences. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(7), 880–894. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1515195

Yorke, M., & Knight, P. (2006). Embedding employability into the curriculum (vol. 3). York, Higher Education Academy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the students and educational experts who participated in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics and consent

Participants were informed about the purpose of the study when they received the invitational email. Participation in the focus groups was voluntary, with anonymous reporting. Participants gave their consent for recording the sessions before the recordings were started.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heymann, P., Hukema, M., van Rosmalen, P. et al. Towards design principles for an online learning platform providing reflective practices for developing employability competences. Educ Inf Technol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12530-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12530-4