Abstract

This study aimed at determining the effect of flipped classroom approach on mathematics achievement and interest of students. Given this, a quasi-experimental design was used, specifically non-equivalent pretest-posttest control group design. The study’s population comprised six hundred and seventy-three seniors in class one (SS 1) from Igbo-Etiti Local Government Area in Enugu State. The study’s participants were a sample of 86 learners selected from two schools purposively. Each school had two SS 1 classes, divided into experimental and control groups via balloting. Data were gathered through the instrumentality of the Mathematics Achievement Test (MAT) and Mathematics Interest Inventory (MII), which have reliability scores of 0.88 and 0.79, respectively. Prior to and following a six-week course of treatment, each group completed a pretest and posttest. SPSS, a statistical tool for social sciences, was applied to analyse the acquired data. The mean and standard deviation were utilised to report the study’s questions, and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was utilised to evaluate the hypotheses at a 0.05 significance level. Results established that learners taught mathematics utilising flipped classroom approach had higher mathematics achievement and interest scores than their peers taught using the conventional approach. Results also revealed that the achievement and interest scores of male and female learners who received mathematics instruction using flipped classroom approach were the same. Considering the findings, recommendations were given, among others, that mathematics teachers should use the flipped classroom approach to assist learners in boosting their achievement and interest in mathematics, especially in geometry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Mathematics is one of the fundamental subjects that must be taken by all students up through the tertiary levels of education, according to the National Policy on Education (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2013). Mathematics is given a lot of weight in the school curriculum from primary to secondary levels, reflecting the importance of the subject to modern society. The fact that students continually perform poorly in mathematics in internal and external exams, despite the subject’s relative importance, is particularly disheartening (Maruta et al., 2022).

Mathematics researchers over the years have identified factors responsible for learners’ poor performance in mathematics, some of which include; the poor foundation of students in mathematics, overcrowded mathematics classes and worn-out mathematics resources, anxiety towards mathematics, poor instructional strategies, lack of resources for teaching and learning mathematics, students and teachers unfavourable attitudes towards mathematics, students’ laziness and disregard for mathematical discipline, teacher’s abrasiveness when teaching mathematics, poor instructional approaches (Mogege & Egara, 2022; Nzeadibe et al., 2019; Okeke et al., 2023), and lack of learners’ retention and interest in mathematics (Egara et al., 2021; Nzeadibe et al., 2020; Osakwe et al., 2023).

One necessity for students to comprehend mathematics and want to learn it is interest. The level of activity one takes is influenced by their level of interest. (Khayati & Payan, 2014). Interest is also a combination of cognitive and affective processes based on positive emotion, personal values and possessing owned knowledge that aligns with the subject interest (Osman & Hamzah, 2020). Interest is an internal factor closely related to a man’s desire for performance, and as such, it can influence students’ achievement (Osman & Hamzah, 2020). Students interested in doing things can pursue such aims rigorously and diligently. Interest plays an important role in teaching and learning, which might lead to increased achievement if one is interested in learning a particular subject (Okeke et al., 2023). Students do not acquire an interest in mathematics through rote memorisation but through appropriate teaching methods (Nzeadibe et al., 2020).

However, implementing appropriate mathematics teaching approaches by teachers would boost the learners’ eagerness to learn (Inweregbuh et al., 2020); as a result, mathematics researchers have been seeking ways to increase students’ achievement and interest in mathematical concepts (Osakwe et al., 2023). The use of the flipped classroom for learning is one method for teaching mathematics that is recommended (Clark, 2015; Didem & Özdemir, 2018; Karadag & Keskin, 2017; Khadjieva & Khadjikhanova, 2019; Nja et al., 2022; Torres-Martín et al., 2022).

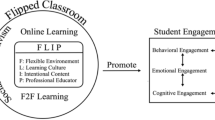

In a flipped classroom, direct instruction is transferred from the setting of group instruction (the classroom) to the setting for individual instruction. The resulting group space is transformed into a lively, interactive learning environment where the teacher helps students apply ideas and actively engage with the course material (Flipped Learning Network) (Omar et al., 2016). The flipped classroom teaching style has materialised due to the technological advancements made possible in the twenty-first century. The flipped classroom approach is reported to have been developed and popularised by Colorado science instructors Jonathan Bergmann and Aaron Sams (Omar et al., 2016). According to Bergmann and Sams (2012), the flipped classroom paradigm includes using Internet technology to convey lectures outside the classroom to optimise the time the lecturer spends interacting with and engaging learners rather than lecturing. Recent learning research suggests that technology can play a major role in reorganising schools and modifying classroom settings to foster deeper, more goal-oriented learning. Computers and the software they utilise, films, and projectors are a few commonly used technology in schools (Gakbish et al., 2021).

The flipped classroom concept changes how instruction is prepared rather than what is taught. Flipped classroom style does not take the instructor’s position; rather, it enables the instructor to work more closely and personally with the learners, using a world different from the one with limited knowledge before the 1990s. According to Bergmann and Sams (2015), “We see flipped learning as a pedagogical solution with an underlying technological component.“ In the words of Bishop and Verleger (2013), “the flipped classroom framework enables the use of various student-centred learning theories and methodologies, including active learning, problem-based learning, peer-assisted and collaborative learning, cooperative learning, and learning styles.”

1.1 Implementing flipped classroom approach

Shorman (2015) states that the flipped classroom method focuses on flipping or inverting the teaching and learning processes. In a traditional education setting, students acquire new knowledge in the classroom. The student then returns home and completes their homework. On the other hand, implementing the flipped classroom method allows students to study new content ahead of time at home by using various digital tools and instructional websites produced and shared by teachers. For example, teachers may create and distribute a 5-to-10-minute video. They can also use multimedia, social media websites, educational games, YouTube for Educational purposes, TED Talk, Khan Academy, iTunes University, or other educational websites to encourage flipped classroom approach (Elian & Hamaidi, 2021). According to Asiksoy and Ozdamli (2016), the flipped classroom approach is student-centred. Students could learn new information at home using smartphones or computer devices. These technological tools allow students to watch instructional videos numerous times to grasp the new knowledge fully.

Furthermore, the students can fast-forward the instructional videos to review previously studied sections and enable them to take notes. The flipped classroom approach considers students’ unique variations, increases productivity, eliminates boredom, and increases passion and learning satisfaction (Asiksoy & Ozdamli, 2016). After examining learning materials, students return to the actual setting of the classroom to put what they have learnt at home into practice. The teacher begins by assessing students’ understanding and revising what they have learned at home; then, they present the activities and group problem-based tasks to be completed in the classroom rather than focusing on classroom time in passively paying attention to the teacher’s elaboration (Elian & Hamaidi, 2021).

The current study implemented the flipped classroom approach in the following ways: (1) The teacher notified the students of the scope and objectives of what they were to experience before, during and after class activities. (2) The students were made to familiarize themselves with the new material before class. The students accessed the online blog created by the researchers that contained created videos, flashcards, and other learning resources on the mathematics contents. (3) The students were motivated by activities embedded in the online blog that enabled them to prepare before class. For instance, students were motivated to do pre-class work by responding to open-ended questions about the accessed materials and attempting to solve some given problems. (4) The students had the opportunity to deepen their understanding of the math contents studied via in-class activities facilitated by the math teachers. To ensure the teachers actively engaged students, they were divided into smaller groups to collaborate, where they discussed their experiences and understanding of the materials learned, and the teacher provided and made necessary clarifications where necessary. (5) The students were given the task to practice and watch 5-minute video lectures on math contents, read online materials provided, finish quizzes related to the information obtained from the video lectures, and complete their tasks. (6) Students were evaluated and assessed after completing the mathematics topic.

1.2 Benefits, Challenges and difficulties of flipped classroom approach

The flipped classroom approach to teaching and learning has a lot of potential benefits, many of which are lauded, as well as some less-publicised potential drawbacks.

1.2.1 Benefits

Potential benefits include the following: Learners can watch videos at their own pace or go over the content more than once (Roehling et al., 2017); lessons can be divided into smaller sections, and learners can view them whenever it is most practical and advantageous (Forsey et al., 2013; Jensen, 2011); in the classroom, active learning, a powerful teaching strategy, can be used (Freeman et al., 2014); students that are struggling can be helped by teachers, who can also establish stronger relationships with them (Roehling et al., 2017); flipped classroom improved student learning outcomes and achievement, increased teacher-student and student-student interactions during sessions, promotion of a student-centric learning environment, and consideration of different styles of learning (Vuong et al., 2018); flipped classroom allows students to learn whenever, wherever, and at their own pace, personalise their educational experience, advance their engagement in learning, enhance their capacity for reflection and general competencies, improve their level of self-discipline and self-regulation abilities, increase their learning independence, and so on (He et al., 2016; Yang, 2017).

1.2.2 Challenges and difficulties

Despite the benefits of flipped classroom approach, there exist some potential drawbacks. Compared to a conventional classroom lecture, students may perceive the recorded lectures to be less engaging and experience more interruptions when watching the vodcast (Jensen, 2011). Milman (2012) stated that students may not watch the entire lesson video or have trouble understanding the content, leaving them unprepared for instructional tasks during class sessions or struggling to keep up with other students. Furthermore, Milman claimed that the environment in which students watch videos might not be optimal for acquiring new ideas. Learners are supposed to be responsible for their educational progress; however, the fact that the virtual version of the flipped class has many distractions could result in inadequate concentration. Learners are frequently distracted by other web pages, social media sites, and their surroundings, rendering them unable to completely concentrate on watching video classes. Students prefer that an instructor be present during the lesson so they can ask questions (Chandra & Fisher, 2009). According to Chen (2016) and Simpson and Richards (2015), one significant challenge is the students’ opposition to a completely different teaching style. Due to their familiarity with traditional teaching formats, students found it difficult to shift to an innovative teaching approach that included new routines, obligations, and demands. Some students struggle more than others to plan, organise, and complete their outside-of-classwork study (Srilatha, 2018); there may be a decline in reading assignment compliance when students view recorded lectures (McLaughlin et al., 2014). The greater amount of outside-of-class time for preparation may have a detrimental effect on the satisfaction of learners’ level, according to Missildine et al. (2013). Pre-class activities may take up too much of the students’ free time. The same results from Strayer (2009) suggest that the flipped classroom places a considerably higher demand on learners due to their new roles. They might experience more pressure to do the pre-class assignments, making the in-class exercises difficult. As a result, the flipped classroom would consequently prove completely ineffective.

Furthermore, it could be difficult for students without as much access to resources, such as money or technology, to download or watch the vodcasts (O’Bannon et al., 2011). Lastly, because the flipped classroom approach greatly depends on independent study and the use of technology, Missildine et al. (2013) identified some challenges with operation linked to infrastructure, classroom accessibility, and constrained high-speed Internet connection. However, while some learners might not be privy to the Internet at home, others might not have computers or other portable gadgets to view video lectures or digital materials.

1.3 Theoretical framework

The study’s theoretical framework is based on Lev Vygotsky’s social constructivist theory, first proposed in 1968. Social constructivism holds that students actively construct knowledge and meaning from their experiences. Constructivism is predicated on the notion that by critically thinking about our experiences, we may increase our understanding of the world. Each person creates standards and mental models to make sense of their experiences. Thus, adapting our mental models to incorporate new knowledge is the essence of learning. Because students construct meaning based on existing information, this idea is connected to the flipped classroom style. Students directly participate in the learning process. During the process, they establish an appropriate learning atmosphere where learners can advance their knowledge rather than giving them direct information. In a flipped classroom, self-regulated learning is the only factor influencing learning outside class. Active learning techniques are used in the classroom to execute high-level cognitive exercises that involve student interaction (Saglam & Arslan, 2018). Therefore, Vygotsky’s theory played a vital role in this study as it enhanced learning and promoted social interaction/activities among learners, in which the mathematics teachers were not always in front of the class for direct instruction. The students efficiently learned socialising via the flipped classroom learning experience, and they learned the mathematics concept through established activities and games that stimulated their zone of proximal development (ZDP), which enhanced their achievement and interest in mathematics.

1.4 Reviewed related studies

Research into the effectiveness of flipped classroom strategies in various academic fields and how it affects students’ achievement and interest on a global and local scale have been conducted in various circumstances. For example, Uy (2022) assessed the effectiveness of using flipped classroom learning approach in enhancing undergraduate students’ mathematics achievement in the Philippines. According to Uy’s findings, the experimental group’s learners who used the flipped classroom method outshined their equals in the control group regarding performance. Another study by Harmini et al. (2022) looked at the impact of flipped classroom-based learning on learners’ calculus achievement in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Their findings demonstrated that students in the experimental group taking calculus using a flipped classroom approach achieved better than their counterparts in the control group. Elian and Hamaidi (2021) examined how the flipped classroom technique affected fourth-grade science achievement among Jordanian learners. Their findings showed that students taught using the flipped classroom style outperformed their counterparts in the control group that utilised the conventional approach.

Another investigation by Wei et al. (2020) that determined the effectiveness of flipped classroom method in improving mathematics achievement of middle school learners in China revealed that learners in the control group that received mathematics lessons using the flipped classroom approach outperformed their peers that received math lessons with the traditional method. Mubarok et al. (2019) investigated the effectiveness of flipped classroom approach on Indonesian undergraduate learners’ achievement in EFL writing across cognitive styles. Their findings revealed that learners in the experimental group who used the flipped classroom model outperformed the control group who used the conventional approach. Another study by Khadjieva and Khadjikhanova (2019) examined how the flipped classroom strategy affected pre-foundation learners at Westminster University in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. They discovered that learners in the experimental group who received Math and English instruction using the flipped classroom strategy outclassed their peers in the control group who received the same instruction using traditional methods. Karadag and Keskin (2017) researched the effects of flipped Learning style on grade 8 learners’ academic achievement in mathematics lessons in Turkey, and they found that students that received mathematics lessons using flipped learning strategy attained superior scores than their peers in the control group.

A study conducted by Efiuvwere and Fomsi (2019) to ascertain the effect of flipped classroom strategy on learners’ interest in mathematics in Rivers State, Nigeria, revealed that the flipped classroom strategy improved learners’ mathematics interest that belonged to the experimental group more than learners in the control group but was not statistically significant. Omile et al. (2021) investigated how flipped classroom technology affected students’ academic performance and interest in English. Their result revealed that learners who received instruction utilising the flipped classroom technology had significantly better performance and increased interest in the English concept than their peers in the control group that received the lesson using the conventional method. The above-reviewed related studies indicate that flipped classroom is a viable approach that enhances students’ achievement and interest in mathematical concepts. But there is little empirical evidence on how well the flipped classroom approach improves learners’ achievement and interest in mathematics and how gender plays a role. Therefore, in filling the gap, there is a need to determine the effect of flipped classroom approach on secondary school learners’ mathematics achievement and interest in Igbo-Etiti LGA of Enugu State, Nigeria, especially in male and female learners.

Gender is a social construct that categorises and divides organisms based on sexual requirements and traditionally prescribed duties (Authors, 2023). These roles could offer insight into people’s methods for solving mathematical issues. One important thing to find out in this study is if gender difference exists among secondary school students’ achievement and interest when flipped classroom approach is utilised. The study by Kutigi et al. (2022) that examined gender differences in using flipped classroom instructional models to improve students’ proficiency in oral-English material found that both male and female learners achieved equally well when the model was applied. Ikwuka and Okoye (2022) looked into how gender and flipped classroom models differed in their influence on CEP students’ academic performance in Basic methodology. Their research demonstrates that when flipped classroom approach was used, learners’ gender did not significantly affect their achievement. Chebotib et al. (2022) investigated the impact of the flipped classroom learning strategy on learners’ biology achievement in Kenya. They discovered that female students achieved much more when the strategy was employed than their male counterparts. The study by Makinde and Yusuf (2017) that examined the effect of flipped classroom learning on students’ achievement in mathematics revealed that male and female students attained similar achievement levels in mathematics when flipped classroom approach was utilised. Enekwechi and Okeke (2017) looked at how gender affects the impact of flipped classroom method on students’ interest, engagement, and achievement in chemistry. Their findings demonstrate that the flipped classroom method equally boosted the interests of male and female learners. A study by Gambari et al. (2016) that looked at how the flipped classroom strategy increased learners’ understanding of the mammalian skeletal system in Minna, Niger State, discovered that both genders profited equally from the flipped classroom approach.

From the reviewed related studies on gender difference, what is known is that flipped classroom approach is gender friendly irrespective of discipline. Another report shows that female students are more responsive to flipped classroom approach than males that received biology instruction (Chebotib et al., 2022). However, what is not known is if flipped classroom approach would benefit both male and female learners’ achievement and interest in mathematics equally or differently in Igbo-Etiti LGA. Therefore, this research aims to determine the effect of flipped classroom approach on secondary school learners’ mathematics achievement and interest in Igbo-Etiti LGA of Enugu State, Nigeria.

1.5 Research questions

The following research questions guided the study.

-

1.

What are the mean achievement scores of students who received mathematics instruction using flipped classroom approach and their peers in the control group?

-

2.

What are the mean achievement scores of male and female students who received flipped classroom approaches?

-

3.

What are the mean interest scores of students who received mathematics instruction using flipped classroom approach and their peers in the control group?

-

4.

What are the mean interest scores of male and female students who received flipped classroom approach?

1.6 Hypotheses

The following hypotheses guided the study.

-

1.

Difference exists between the mean achievement scores of students who received mathematics instruction using flipped classroom approach and their peers in the control group.

-

2.

Difference exists between the mean achievement scores of male and female students who received mathematics instruction using flipped classroom approach.

-

3.

Difference exists between the mean interest scores of students who received mathematics instruction using flipped classroom approach and their peers in the control group.

-

4.

Difference exists between the mean interest scores of male and female students who received mathematics instruction using flipped classroom approach.

2 Method

This quasi-experimental research study design used a non-equivalent control group for the pretest and posttests. The design was employed rather than randomly allocating students to groups because it is impractical to do so in quasi-experimental research (Fraenkel et al., 2023; Nworgu, 2015; Rogers & Révész, 2019). The quasi-experimental design has recently been used in similar studies (Egara et al., 2022; Oguguo et al., 2021). The research was conducted with a population of 673 SS1 students from 15 public secondary schools in Enugu State’s Igbo-Etiti Local Government Area (Post Primary School Management Board, 2022). A sample of 86 pupils (39 males and 47 females) was selected from two schools purposively. The reason for purposively selecting the two schools is that they are the only schools with Information and communication technology (ICT) facilities and electricity. The selected schools had two streams of SS 1 classes, divided into experimental and control groups via balloting. The study’s instruments were the Mathematics Achievement Test (MAT) and Mathematics Interest Inventory (MII). The researchers created 20 multiple-choice items on the MAT, which served as the major instrument for the study. The MAT items were created using a test blueprint to ensure adequate coverage of the study’s subject and maintain a consistent distribution across the various cognitive domain levels. The MII, however, was adapted from Snow’s (2011) math interest inventory. The MII consists of 20 items and uses a 4-point Likert-type scale with the following options: strongly agree (4), agree (3), disagree (2), and strongly disagree (1). The researchers developed two lesson plans/notes for the experimental and control groups. Three research experts, two of whom are experts in Mathematics Education and the other of whom is an expert in Measurement and Evaluation, validated the MAT, MII and lesson plans/notes. Both the MAT and MII were trial tested. The reliability coefficient for the MAT was determined to be 0.88 utilising the Kuder-Richardson formula 20. However, the internal consistency of the MII was calculated utilising Cronbach’s Alpha, and the reliability coefficient was found to be 0.79.

Before the commencement of the research, approval was granted by the Post Primary Management Board, Nsukka Zonal office, Enugu State, on September 6, 2022, with reference No. REC/PPSMB/22/0460. The investigation was also permitted by the heads of the two chosen schools. The regular math teachers at the selected schools worked as the study’s research assistants. The researchers provided them with a week of training on how to apply and teach the mathematics concept (Geometry: Circle Theorems) using the flipped classroom approach. Lesson plans/notes were provided to the math teachers in both groups as a resource. The lesson plan/note for the experimental group was created following the flipped classroom approach that included activities with video resources and materials. The lesson plan/note for the control group was created utilising the conventional approach. Before starting the treatment, the SS 1 students took a pretest. The treatment ran for four weeks. The fifth week saw the administration of the posttest (see Fig. 1). The posttest items are the same as the pretest items; however, they were rearranged to give them a new look and avoid memory effects. The posttest results were noted and utilised to present information on learners’ mathematics achievement and interest by gender and treatment group. The SPSS software version 28 was used to analyse the collected data. The mean (\(\stackrel{-}{\text{X}}\)) and standard deviation (SD) were used to answer the study’s research questions, and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was utilised to test the hypotheses at a significance level of 0.05. The reason for the choice of ANCOVA was to establish equality of baseline pre-test data before the commencement of the treatment. ANCOVA helped to establish the covariates between the pre-test and post-test.

3 Result

The results are given per the questions and hypotheses guiding the study.

RQ 1

What are the mean achievement scores of students who received mathematics instruction using flipped classroom approach and their peers in the control group?

Table 1 presents the mean achievement score of learners assigned to both groups. The learners in the experimental group obtained an average pretest score of 60.8 (SD = 7.7) and a mean posttest rating of 86.1 (SD = 9.9), indicating a mean difference of 25.3. In contrast, those in the control group scored an average of 62.0 (SD = 7.6) on the pretest and had a mean achievement score of 64.7 (SD = 8.9), showing a mean difference of only 2.7. As a result, learners in the experimental group showed greater mean achievement scores than their counterparts in the control group.

HO1

Difference exists between the mean achievement scores of students who received mathematics instruction using flipped classroom approach and their peers in the control group.

Table 2 reveals the ANCOVA of the variation in achievement scores between the experimental group’s students taught utilising flipped classroom approach and their peers in the control group who utilise the conventional approach. The outcome showed that treatment groups had a significant main effect, F(1, 81) = 114.031, p = .000. The null hypothesis that the achievement scores of learners who received math instruction through flipped classroom approach and those in the control group did differ was not rejected because the p-value (0.000) is less than the threshold of significance set at p < .05. Therefore, we concluded that difference exists between the mean achievement scores of students who received mathematics instruction using flipped classroom approach and their peers in the control group, favouring learners in the experimental group. The result further divulged that the effect size (partial eta squared) was 0.585, which implies that a 58.5% variation in students’ achievement scores was attributed to the flipped classroom approach alone.

RQ 2

What are the mean achievement scores of male and female students who received flipped classroom approaches?

Table 3 presents the mean achievement scores of male and female learners in the experimental group who received mathematics instructions using the flipped classroom approach. The mean pretest ratings for the male learners were 63.2 (SD = 5.8), and the mean posttest rating was 84.9 (SD = 9.8), with a mean difference of 21.7. The mean pretest ratings for female students were 58.8 (SD = 8.6), and the mean posttest rating was 87.2 (SD = 10.1), with a mean difference of 28.4. Thus, it was observed that the mean achievement scores of female learners were higher than those of males.

HO2

Difference exists between the mean achievement scores of male and female students who received mathematics instruction using flipped classroom approach.

The data analysis in Table 2 was utilised to test Hypothesis 2. The ANCOVA of the difference between the achievement scores of male and female learners in the experimental group who received mathematics instruction utilising the flipped classroom style is also displayed in the table. The result showed no significant effect for Gender F(1, 81) = 0.105, p = .747. However, given that p-value (0.747) is greater than the significance level set at p > .05, the null hypothesis of significant difference is rejected. Therefore, we concluded no differences exist between the mean achievement scores of male and female learners who received mathematics instruction utilising flipped classroom approach.

RQ 3

What are the mean interest scores of students who received mathematics instruction using flipped classroom approach and their peers in the control group?

The average interest scores of the experimental and control groups of learners are shown in Table 4 above. Learners in the experimental group had a mean pretest score of 58.7 (SD = 6.4) and a mean posttest score of 68.4 (SD = 6.0), with the mean difference computed as 9.7. However, learners in the control group had a mean pretest score of 57.8 (SD = 6.9) and a posttest mean score of 57.6 (SD = 7.4), with a mean difference of 0.2. As a result, learners in the experimental group had greater mean interest scores than their counterparts in the control group.

HO3

Difference exists between the mean interest scores of students who received mathematics instruction using flipped classroom approach and their peers in the control group.

The ANCOVA of the disparity in interest scores between the experimental group’s students who received teaching using flipped classroom approach and their counterparts in the control group who received conventional instruction is displayed in Table 5. The outcome showed that treatment groups had a significant main effect, F(1, 81) = 58.523, p = .000. The null hypothesis that the interest scores of learners who received math lessons through flipped classroom approach and those in the control group differed was not rejected because the p-value (0.000) is less than the threshold of significance set at p < .05. Therefore, we concluded that difference exists between the mean interest scores of students who received mathematics instruction using flipped classroom approach and their peers in the control group, favouring learners in the experimental group. The result further divulged that the effect size (partial eta squared) was 0.419, which implies that a 41.9% variation in students’ interest scores was attributed to the flipped classroom approach alone.

RQ 4

What are the mean interest scores of male and female students who received flipped classroom approaches?

Table 6 presents the experimental group’s mean interest scores for both genders of students who received mathematics instructions using the flipped classroom approach. The mean pretest scores for the male learners were 57.5 (SD = 6.5), and the mean posttest score was 68.9 (SD = 4.8), with a mean difference of 11.4. The mean pretest scores for female students were 59.8 (SD = 6.3), and the mean posttest score was 68.0 (SD = 7.0), with a mean difference of 8.2. As a result, it was shown that male students’ mean interest scores were higher than those of female learners.

HO4

Difference exists between the mean interest scores of male and female students who received mathematics instruction using flipped classroom approach.

The data analysis in Table 5 was utilised to evaluate Hypothesis 4. The ANCOVA of the difference in male and female learners’ experimental group interest scores who received mathematics instruction utilising the flipped classroom approach is also displayed in the table. The result showed no significant effect for Gender F(1, 81) = 0.302, p = .584. However, given that p-value (0.584) is greater than the significance level set at p > .05, the null hypothesis of significant difference is rejected. Therefore, we concluded that no differences exist between the mean interest scores of male and female learners who received mathematics instruction utilising flipped classroom approach.

4 Discussion

The findings revealed that students that received mathematics instruction utilising flipped classroom approach achieved the mathematics concept better than those who received the same concept using the conventional method. The test of hypothesis one further established that learners in the experimental group that received mathematics lessons using flipped classroom approach achieved better than their peers in the control group that was taught the same concept utilising the conventional approach. Thus, the flipped classroom approach successfully enhanced students’ achievement in mathematics, particularly geometry. This discernible variation may have resulted from the students’ direct participation in learning and interpersonal interaction with video resources and materials utilised in the flipped learning environment. Another reason for students’ high performance could be that they appreciated learning at their own pace and the creation of engaging lessons (practical) by the math teachers. The finding agrees with the results of Uy (2022), that declared that learners in the experimental group that received math lessons through flipped classroom method attained significantly better scores than their peers in the control group. The finding also corroborates the results of Harmini et al. (2022), who disclosed that learners in the experimental group who learnt calculus using flipped classroom approach attained higher than their counterparts in the control group. The finding of this study equally supports the result of Wei et al. (2020), which revealed that students in the control group that received mathematics lessons using the flipped classroom approach outperformed their peers that received math lessons with the traditional method significantly.

Furthermore, the study showed that male learners achieved the mathematics concept better than their female counterparts when the flipped classroom approach was utilised. However, further analysis showed by testing hypothesis two that no significant differences exist between the achievement scores of male and female learners who received mathematics lessons utilising the flipped classroom approach. The outcome of the no significant differences could be that both genders showed the same enthusiasm, motivation, and engagement in learning the mathematics concept using the flipped classroom approach. It could also be that both male and female learners built the same level of deeper understanding through active learning towards the mathematics concept. The finding supports the result of Makinde and Yusuf (2017), who examined the effect of flipped classroom strategy on learners’ mathematics achievement, and their result revealed that male and female learners attained similar achievement levels in mathematics when flipped classroom approach was utilised. The finding also relates to the finding of Kutigi et al. (2022) that showed that both male and female learners achieved equally when flipped classroom model was utilised for Oral-English content. The finding equally relates to the result of Ikwuka and Okoye (2022), who reported that students’ achievement was not significantly influenced by their gender when flipped classroom approach was utilised for Basic methodology.

Likewise, the findings revealed that students who received mathematics instruction using flipped classroom approach had their interest increased in the mathematics concept compared to their counterparts who received the same concept using the conventional method. Accordingly, a further test of hypothesis three established that learners in the experimental group held increased interest levels in the mathematics concept than their peers in the control group. Thus, it concluded that the flipped classroom approach successfully enhanced learners’ interest in the mathematics concept taught. The increased interest could have been caused by the students’ interpersonal interaction with video resources and materials in the flipped classroom environment. Another possible reason could be that learners found their time more interesting in the classroom. Another reason could be that students were more emotionally invested and engaged in the mathematics concept taught. The finding relates to the result of Omile et al. (2021), who revealed that students who received instruction utilising the flipped classroom method had a significantly increased interest in English concepts compared to their peers in the control group that received the English instruction utilising the conventional strategy. However, the finding disagrees with the result of Efiuvwere and Fomsi (2019), who, in their study, revealed that flipped classroom strategy did not substantially enhance students’ interest in mathematics. However, they reported that learners in the experimental group had increased math interest more than their peers in the control group, but it was not statistically significant. The rationale for the difference could be that the learners and teachers lacked functioning facilities and were not used to using technology for academic purposes.

Moreover, the study’s findings indicated that male learners exhibited more interest in mathematics than females when the flipped classroom approach was utilised. Consequently, further analysis by testing hypothesis four divulged no significant difference between the interest scores of male and female learners who received mathematics instruction utilising the flipped classroom strategy. The outcome of the no significant difference could be that both male and female learners showed the same degrees of interest and engagement in learning the mathematics concept. The finding relates to the result of Enekwechi and Okeke (2017), who showed that both male and female learners’ interests were equally enhanced by flipped classroom approach.

5 Conclusions

The flipped classroom approach significantly enhanced learners’ achievement and interest in the mathematics concept taught. This was seen in the mean achievement and interest scores of students in the experimental group, which were higher than their counterparts in the control group. Again, the achievement and interest scores of male and female learners who received mathematics instruction using flipped classroom approach were the same. This means that learners of both sexes that utilised the flipped classroom approach benefited equally from the treatment. This research contributes significantly to mathematics education because it is the first to explore the flipped classroom approach’s effect on learners’ achievement and interest in mathematics, particularly geometry, in the Igbo-Etiti LGA. The study also explains to mathematics education specialists how the flipped classroom approach can help learners enhance their achievement and interest levels in mathematics, particularly geometry.

5.1 Limitation

The results of this study might not apply to students at other secondary school levels because it only included SS 1 students. This is because the SS 1 students in this study might not have the same traits as their peers in other secondary school levels, particularly in different Education Zones in the State. Therefore, future research should include other secondary school levels. Furthermore, only quantitative data was utilised to assess how utilising flipped classroom approach affected learners’ achievement and interest in geometry concepts. Future research should make use of qualitative data, incorporating scheduled interviews.

5.2 Recommendation

The recommendations below are suggested based on the study’s findings:

-

(i)

Math teachers should use the flipped classroom approach to teach geometry theorems and proofs to boost learners’ achievement and interest in mathematics.

-

(ii)

The government and relevant education bodies should organise seminars and workshops for mathematics teachers on using flipped classroom approach in teaching and learning mathematical concepts.

-

(iii)

School principals should ensure the availability of ICT resources and materials that would enable the smooth usage of the flipped classroom approach to boost learners’ mathematics achievement and interest.

Data Availability

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Asiksoy, G., & Ozdamli, F. (2016). Flipped classroom adapted to the ARCS model of motivation and Applied to a physics course. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics Science & Technology Education, 12(6), 1589–1603.

Bergmann, J., & Sams, A. (2012). Flip your classroom: Reach every student in every class every day. International Society for Technology in Education.

Bergmann, J., & Sams, A. (2015). Flipped learning for math instruction. International Society for Technology in Education. VA.

Bishop, J., & Verleger, M. (2013). The flipped classroom: A survey of the research. In ASEE National Conference Proceedings.

Chandra, V., & Fisher, D. L. (2009). Students’ perceptions of a blended web-based learning environment. Learning Environments Research, 12(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-008-9051-6.

Chebotib, N., Too, J., & Ongeti, K. (2022). Effects of the flipped learning approach on students’ academic achievement in secondary schools in Kenya. Journal of Research & Method in Education, 12(6), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.9790/7388-1206030110.

Chen, L. L. (2016). Impacts of flipped classroom in high school health education. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 44(4), https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239515626371. 411 – 420.

Clark, K. (2015). The Effects of the flipped model of instruction on Student Engagement and Performance in the secondary Mathematics Classroom. The Journal of Educators Online, 12(1), 91–115. https://doi.org/10.9743/jeo.2015.1.5.

Didem, A. S., & Özdemir, S. (2018). The Effect of a flipped Classroom Model on Academic Achievement, Self-Directed Learning Readiness, Motivation and Retention *. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Technology, 6(1), 76–91. www.mojet.net.

Efiuvwere, R. A., & Fomsi, E. F. (2019). Flipping the mathematics classroom to enhance senior secondary students’ interest. International Journal of Mathematics Trends and Technology, 65(2), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.14445/22315373/ijmtt-v65i2p516.

Egara, F. O., Eseadi, C., & Nzeadibe, A. C. (2021). Effect of computer simulation on secondary school students’ interest in algebra. Education and Information Technologies, 27, 5457–5469.

Elian, S. A., & Hamaidi, D. A. (2021). The effect of using flipped learning strategy on the academic achievement of eighth-grade students in Jordan. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 12(8), 534–541. https://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2021.0120862.

Enekwechi, E. E., & Okeke, S. O. C. (2017). Effects of flipped classroom instruction on secondary school students’ interest, participation and academic achievement in chemistry [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Nnamdi Azikiwe University. https://phd-dissertations.unizik.edu.ng/repos/81192823200_144523225296.pdf.

Federal Republic of Nigeria. (2013). National Policy on Education (6th Edition.). NERDC.

Forsey, M., Low, M., & Glance, D. (2013). Flipping the sociology classroom: Towards a practice of online pedagogy. Journal of Sociology, 49(4), 471–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783313504059.

Fraenkel, J. R., Wallen, N. E., & Hyun, H. H. (2023). How to design and evaluate research in education (11th ed.). McGraw Hill.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(23), 8410–8415. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1319030111.

Gakbish, J. G., Godfrey, G. G., & Yilleng, A. M. (2021). Effect of geogebra software on senior secondary students’ academic achievement in algebra in Pankshin LGA of Plateau State. The Journal of the Mathematical Association of Nigeria, 46(1), 170–177.

Gambari, A. I., Bello, R. M., Agboola, A. K., & Adeoye, I. O. (2016). Impact of flipped classroom instructional model on students’ achievement and retention of mammalian skeletal system in Minna, Niger State, Nigeria. International Journal of Applied Biological Research, 12(1), 579–587. http://jurtek.akprind.ac.id/bib/rancang-bangun-website-penyedia-layanan-weblog.

Harmini, T., Sudibyo, N. A., & Suprihatiningsih, S. (2022). The Effect of the flipped Classroom Learning Model on Students’ Learning Outcome in Multivariable Calculus Course. AlphaMath: Journal of Mathematics Education, 8(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.30595/alphamath.v8i1.10854.

He, W., Holton, A., Farkas, G., & Warschauer, M. (2016). The effects of flipped instruction on out-of-class study time, exam performance, and student perceptions. Learning and Instruction, 45, 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.07.001.

Ikwuka, O. I., & Okoye, C. C. (2022). Differential effects of flipped classroom and gender on nigerian federal universities CEP students’ academic achievement in basic methodology. African Journal of Educational Management Teaching and Entrepreneurship Studies, 2, 106–118.

Inweregbuh, O. C. Ugwuanyi, C. C., Nzeadibe, A. C., Egara, F. O., & Emeji, I. E. (2020). Teachers’ practices of creativity in mathematics classroom in basic education. International Journal of Research Publications, 55(1). https://doi.org/10.47119/ijrp100551620201254

Jensen, S. A. (2011). In-class versus online video lectures: Similar learning outcomes, but a preference for in-class. Teaching of Psychology, 38(4), 298–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628311421336.

Karadag, R., & Keskin, S. S. (2017). The effects of flipped learning approach on the academic achievement and attitudes of the students. New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences, 4(6), 158–168. https://doi.org/10.18844/prosoc.v4i6.2926.

Khadjieva, I., & Khadjikhanova, S. (2019). Flipped classroom strategy effects on students’ achievements and motivation: Evidence from CPFS level 2 students at Wiut. European Journal of Research and Reflection in Educational Sciences, 7(12), 120–130. www.idpublications.org.

Khayati, S., & Payan, A. (2014). Effective factors increasing the students’ interest in Mathematics in the Opinion of Mathematic Teachers of Zahedan. International Journal of Educational and Pedagogical Sciences, 8(9), 3077–3085.

Kutigi, U., Gambari, I., Tukur, K., Yusuf, T., Daramola, O., & Abanikannda, O. (2022). Gender differentials in the Use of flipped Classroom Instructional Models in enhancing achievement and Retention in oral-english contents of senior secondary School in Minna, Niger State, Nigeria. International Journal of Advanced Humanities Research, 2(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.21608/ijahr.2022.256372.

Makinde, S., & Yusuf, M. O. (2017). The flipped classroom: Its effects on students’ performance and retention in secondary school mathematics classroom. International Journal of Innovative Technology Integration in Education, 1(1), 117–126. https://ijitie.aitie.org.ng/index.php/ijitie/article/view/43.

Maruta, S. I., Bolaji, C., Musa, M., & Ibrahim, M. O. (2022). Effects of Polya and Bransford-stein models on students’ performance in trigonometry, among senior secondary school students in Kano State, Nigeria. The Journal of the Mathematical Association of Nigeria, 47(2), 7–14.

McLaughlin, J. E., Roth, M. T., Glatt, D. M., Gharkholonarehe, N., Davidson, C. A., Griffin, L. M., Esserman, D. A., & Mumper, R. J. (2014). The flipped classroom: A course redesign to foster learning and engagement in a health professions school. Academic Medicine, 89(2), 236–243. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000086.

Milman, N. B. (2012). The flipped classroom strategy: What is it, and how can it best be used? Distance Learning, 9(3), 85–87.

Missildine, K., Fountain, R., Summers, L., & Gosselin, K. (2013). Flipping the classroom to improve student performance and satisfaction. Journal of Nursing Education, 52(10), 597–599. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20130919-03.

Mosimege, M. D. & Egara, F. O. (2022). perception and perspective of teachers towards the usage of ethno-mathematics approach in mathematics teaching and learning. Multicultural Education, 8(3), 288–298.

Mubarok, A. F., Cahyono, B. Y., & Astuti, U. P. (2019). Effect of flipped Classroom Model on Indonesian EFL Students’ writing achievement across cognitive Styles. Dinamika Ilmu, 19(1), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.21093/di.v19i1.1479.

Nja, C. O., Orim, R. E., Neji, H. A., Ukwetang, J. O., Uwe, U. E., & Ideba, M. A. (2022). Students’ attitude and academic achievement in a flipped classroom. Heliyon, 8(1), e08792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08792.

Nworgu, B. G. (2015). Educational measurement and evaluation: Theory and practice. University Trust Publishers.

Nzeadibe, A. C., Egara, F. O., Inweregbuh, C. O., & Osakwe, I. J. (2020). Effect of problem-solving and collaborative strategy on secondary school students’ retention in geometry. African Journal of Science, Technology and Mathematics Education, 5(1), 9–20.

Nzeadibe, A. C., Egara, F. O., Inweregbuh, O. C., & Osakwe, I. J. (2019). Effect of two meta-cognitive strategies on students’ achievement in mathematics. Journal of CUDIMAC, 7(1),43–57.

O’Bannon, B. W., Lubke, J. K., Beard, J. L., & Britt, V. G. (2011). Using podcasts to replace lecture: Effects on student achievement. Computers and Education, 57(3), 1885–1892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.04.001.

Okeke, A. M., Egara, F. O., Orga, A. C., & Nzeadibe, A. C. (2023). Effect of symbolic form model on students ’ interest in logic content of the mathematics curriculum. Pedagogical Research, 8(2), em0159. https://doi.org/10.29333/pr/13077

Omar, A., Miah, M., & Ellis, K. (2016). Flipping a class: Impact on performance and retention. International Journal of Networks and Systems, 5(1), 10–15. http://www.warse.org/IJNS/static/pdf/file/ijns02512016.pdf.

Omile, J. C., Uloh-bethels, A. C., Ugwuanyi, E. I., Obiezu, M. N., Osigwe, N. A., & Ezeife, O. N. (2021). Effects of flipped classroom technology on students’ interest and achievement in english language reading comprehension. International Journal of Mechanical and Production Engineering Research and Development, 11(4), 157–164. https://issuu.com/tjprc/docs/2-67-1624683393-13ijmperdaug202113.

Osakwe, I. J., Egara, F. O., Inweregbuh, O. C., Nzeadibe, A. C., & Emefo, C. N. (2023). Interaction pattern approach: An approach for enhancing students’ retention in geometric construction. International Electronic Journal of Mathematics Education, 18(1), em0720. https://doi.org/10.29333/iejme/12596

Osman, N., & Hamzah, M. I. (2020). Impact of implementing blended learning on students’ interest and motivation. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(4), 1483–1490. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.080442.

Post, P. M. B. (2022). School enrolment statistics in Nsukka Education Zone. Nsukka Zonal Office.

Roehling, P. V., Luna, R., Richie, L. M., F. J., & Shaughnessy, J. J. (2017). The benefits, drawbacks, and challenges of using the flipped classroom in an introduction to psychology course. Teaching of Psychology, 44(3), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628317711282.

Rogers, J., & Révész, A. (2019). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs. Physical Review B, 111, 133–143.

Saglam, D., & Arslan, A. (2018). The Effect of flipped Classroom on the academic achievement and attitude of higher education students. World Journal of Education, 8(4), 170. https://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v8n4p170.

Shorman, A. (2015). Blended learning as flipped learning. Amman.

Simpson, V., & Richards, E. (2015). Flipping the classroom to teach population health: Increasing the relevance. Nurse Education in Practice, 15(3), 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2014.12.001.

Srilatha, R. (2018). Flipped classrooms: Advantages and disadvantages. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research in Arts and Humanities, 3(1), 307–309.

Strayer, J. (2009). Inverting the classroom: A study of the learning environment when an intelligent tutoring system is used to help students learn. VDM.

Torres-Martín, C., Acal, C., El-Homrani, M., & Mingorance-Estrada, Á. C. (2022). Implementation of the flipped classroom and its longitudinal impact on improving academic performance. Educational Technology Research and Development, 70(3), 909–929. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-022-10095-y.

Uy, J. S. (2022). Flipped classroom and students’ academic achievement in mathematics. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 12(10), 424–429. https://doi.org/10.29322/ijsrp.12.10.2022.p13057.

Vuong, N. H. A., Tan, C. K., & Lee, K. W. (2018). Students’ perceived Challenges of attending a flipped EFL Classroom in Viet Nam. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 8(11), 1504. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0811.16.

Wei, X., Cheng, I. L., Chen, N. S., Yang, X., Liu, Y., Dong, Y., Zhai, X., & Kinshuk (2020). Effect of the flipped classroom on the mathematics performance of middle school students. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(3), 1461–1484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09752-x.

Yang, C. C. R. (2017). An investigation of the use of the flipped classroom pedagogy in secondary english language classrooms. Journal of Information Technology Education: Innovations in Practice, 16, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.28945/3635.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those that contributed positively towards the success of this study, most especially the participants for their precious time. We also would like to appreciate the authors whose works were cited for the study.

Funding

Not applicable.

Open access funding provided by University of the Free State.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author 1 conceived the study and carried out data analysis. Author 2 prepared the introduction, presented the results and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

No competing interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Egara, F.O., Mosimege, M. Effect of flipped classroom learning approach on mathematics achievement and interest among secondary school students. Educ Inf Technol 29, 8131–8150 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-12145-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-12145-1