Abstract

Literature emphasizes that gamification significantly enhances students’ engagement in learning and their motivation level. Studies have also examined the benefits of gamification in learning across different levels of education. However, the focus on academics’ pedagogical understanding, knowledge, and skills and how they utilize these in planning and carrying out their gamified lessons particularly in the context of higher education, are not well researched. A mixed-methods study was conducted at a Malaysian public university with the aim of uncovering the practices, purposes, and challenges of integrating gamification via technology from the academics’ perspective. Findings show the academics’ practices of gamification could be further enhanced and their pedagogical considerations revolve around five main themes: (i) motivating students’ learning; (ii) facilitating thinking skills and solving problems; (ii) engaging students’ learning; (iv) facilitating interactions and (v) achieving specific teaching and learning goals. Based on the findings, the researchers proposed two models that would be able to facilitate and enhance academics’ pedagogical knowledge and skills in integrating gamification for students’ learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The widely accepted notion of 21st century education emphasizes learning that augments student-centeredness, creativity, communication, collaboration, critical thinking, and cultural awareness. These emphases, although could be achieved without technology, tend to spark educators’ interest in utilizing various technological tools in teaching and learning. As information and communication technologies (ICTs) become more ubiquitous and affordable, educators often adopt and adapt to create meaningful learning experiences (Huang et al., 2019; Meier, 2021; Nasution, 2021; Tan et al., 2022). However, academics soon realize that technological intervention alone is insufficient. As pointed by many researchers and educationists, achieving the goals of 21st century education requires educators to master a myriad of pedagogies that engage learners (Wang, 2022) and impel them to conceptualize and solve problems. These should be achieved by a “concurrent shift in the role and attitudes of the instructor” (Wismath, 2013, p. 88). This means that educators need to rethink their current pedagogical philosophies to encompass a gamut of teaching and learning practices. Thus, there is an apparent need for educators to equip themselves with innovative pedagogies in designing lessons that offer opportunities for learners to acquire 21st Century Learning Skills (21CL), while integrating appropriate technologies (Vikas & Mathur, 2022).

One notable innovative pedagogy that has received widespread attention in recent years is gamification. It is regarded as one of the pedagogical approaches that may contribute significantly to the development of students’ 21CL (Zainuddin, 2018) and promote active learning (Murillo-Zamorano et al., 2021). Gamification integrates game elements such as points, badges and rewards in a learning environment (Seaborn & Fels, 2015; Swacha, 2021). These elements are used to increase learner motivation and engagement, as research in gamification has predominantly demonstrated a significant linkage between increased motivation, effort and time spent on a task and learning performance among students (Chans & Portuguez-Castro, 2021; Dichev & Dicheva, 2017). The positive results from gamification research have triggered the influx of various tools and applications that are developed to assist educators in designing gamified lessons (Kasurinen & Knutas, 2018).

With more gamification tools available, there is a sudden surge in using the tools by educators (from K-12 to higher education). This is because educators pay much more attention to direct adoption of gamification tools (due to the novelty and current trends) instead of pedagogical aspects that should/would contribute to a more purposeful and meaningful learning. Findings from existing studies in gamification have pointed out the necessity for educators to align the approach with not only intended learning outcomes but also theories that inform successful design of gamified lessons (Domínguez et al., 2013; Gupta & Goyal, 2022). Although significant framework, method and approaches have been created and experimented in recent years, there are still insufficient studies that consider academics as an integral part of the gamification process, particularly in higher education (Moore-Russo et al., 2018). Furthermore, Nacke and Deterding (2017) suggested that research on gamification should move from the fundamental issues of ‘why?’ and ‘what?’ to more complex questions of ‘how?’, ‘when?’ and ‘how and when not?’. This call coincides with the fact that, in terms of teaching, not much is known about academics’ actual practices and intended reasons for using gamification and hence, our motivation for undertaking the current study. Recent SLR studies also show that findings on gamification results are inconsistent and thus, more understanding is needed to further advance our knowledge in the use of gamification for learning (Oliveira et al., 2022). With new and fresh perspectives gained from further research, academics would be able to equip themselves with a more concrete, clear, and structured approach to their practice of gamification in teaching and learning (Lai & Bower, 2020).

Realizing the gap in the existing gamification research that fail to bridge practices and purposes, we argue that understanding academics’ pedagogical practices actually indicates their pedagogical understanding, knowledge and skills that they utilize in planning and carrying out their lessons in achieving the intended learning outcomes (Torrisi-Steele & Drew, 2013). At this juncture, it is important to note that gamification does not necessarily mean the inherent use of technology, but many studies of gamification involve technologies (Boyle et al., 2016) due to the increasing number of technologies made available to create gamified lessons (Kasurinen & Knutas, 2018). From the academics’ perspectives, the literature also highlights the challenges faced as they grapple with the effective integration of gamification using technology. These challenges include relating, connecting, and transforming pedagogical goals to game mechanics (Guenaga et al., 2013) and “understanding of how to gamify an activity depending on the specifics of the educational context” (Dichev & Dicheva, 2017, p. 25). Based on these concerns, we aim to examine academics’ planning, implementation, and assessment of gamification (with technology) in their courses, from the lenses of pedagogical knowledge, skills, practices, considerations or reasonings, and the challenges faced. The research questions that guide this research are:

-

1.

What are the academics’ practices of gamification in their courses?

-

2.

Why do academics integrate gamification in their courses?

-

3.

What are the challenges faced by academics in integrating gamification in their courses?

2 Related studies and research gap

In the area of gamification and learning, an exponential number of review analysis is published from 2010 to 2021 (for example, Faiella & Ricciardi, 2015; Gorbanev et al., 2018; Junior et al., 2019; Majuri et al., 2018; Nacke & Deterding, 2017; Perryer et al., 2016; Shahid et al., 2019; Subhash & Cudney, 2018; Swacha, 2021; Zainuddin et al., 2020). These reviews are the attestations of how extensively and immensely the research in the field of gamification and learning has grown and expanded, especially in the 21st century where learners access to an assortment of digital devices. This compels academics to constantly update their knowledge and pedagogical skills (Santos-Villalba, et al., 2020) in ensuring effective and successful use of gamification pedagogy. Unfortunately, there is a lack of focus on this facet of the gamification pedagogy, as consistently implied by many researchers (Nacke & Deterding, 2017; Sánchez-Mena & Martí-Parreño, 2017). In terms of higher education, Figg and Jaipal-Jamani (2018), who examined characteristics of games, motivational elements of gameplay and, application of gamification for teacher education, emphasize the need for academics to further develop knowledge about “incorporating gamification as an instructional strategy” (p. 1215) that would engage digital learners and accommodate their digital learning preferences.

The current study attempts to address, in a meaningful way, the current lack of knowledge and understanding of academics’ pedagogical practices in terms of gamification. It aims to provide guidance on how to plan, design, implement and assess courses integrating gamification as an instructional strategy. In this respect, unfortunately, there is limited research. For example, Sánchez-Mena and Martí-Parreño (2017) found that academics inherently display four drivers and are faced with four main barriers when they adopt gamification for their courses. The drivers include the capacities and abilities of gamification to i) attract students’ attention, ii) motivate students, iii) facilitate interactive learning and, iv) facilitate students’ learning, while the four barriers are: i) lack of resources, time and facilities, ii) students’ lack of interest, iii) short-term impact, and iv) uncontrolled learning in the classroom. However, the study by Sánchez-Mena and Martí-Parreño (2017) relies on a single source of data (i.e., online structured interview), which is a substantial limitation that might lead to incomplete findings.

Other elements that may determine and affect academics’ teaching using gamification include, attitude towards gamification (Gupta & Goyal, 2022; Martí-Parreño et al., 2016), knowledge on designing courses that incorporate gamification (Figg & Jaipal-Jamani, 2018), knowledge on designing and developing innovative instructions (Zainuddin et al., 2020), creativity in developing attractive and engaging contents (Muntean, 2011) and level of technology available (Zainuddin et al., 2020).

Nonetheless, of late, this specific area of research seems to gain momentum. For instance, Howard (2022) examines the socio-material imbrications of gamification practices of academics and modulates the identities of the academics in terms of gamification usage for teaching and learning. Howard (2022) identifies two types of academics who are creative and positive about gamification – ‘creative, collaborative content developer’ and ‘motivational performer’ – and two types of academics who are reluctant and negative when it comes to implementing gamification pedagogy – ‘school teacher’ and ‘disconnected educator’. Howard (2022) postulates that these four identities are indications that academics still have normative practices and unclear understandings of gamification pedagogy, which may create indecision and ambiguity in terms of teaching and learning. In a nutshell, the above previous studies indicate there is a research gap concerning the use of the gamification pedagogy in HE, especially academics’ practices and pedagogical reasoning, which is examined in the current study.

3 Conceptual framework for gamification in higher education

This study aims to shed light in terms of the academics’ practices and reasons for the use of gamification, guided by the “Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge” (TPCK) framework suggested by Mishra and Koehler (2006). TPCK is structured as an overarching lens to identify and understand academics’ gamification, as it can “transform the conceptualization and the practice of teacher education, teacher training, and teachers’ professional development” (p. 1020). This firmly complements the aim of the study to reify a research-based gamification guidance for academics.

TPCK, which consists of a tripartite of inter-related complex interplay of overlapping components (Fig. 1), postulates that the integration of gamification (with technology) “requires a thoughtful interweaving of all three key sources of knowledge: technology, pedagogy, and content” (Mishra & Koehler, 2006, p. 1029). Hence, the research focused on the fundamental principle that quality teaching requires “a nuanced understanding of the complex relationships between technology, content, and pedagogy, and using this understanding to develop appropriate, context-specific strategies and representations” (Mishra & Koehler, 2006, p. 1029). Thus, the items developed for the research instruments are partly based on this nuanced understanding proposed by Mishra and Koehler (2006). Also, this approach would give us a clear depiction of the academics’ practices of gamification, as well as critical insights into their pedagogical practices that are based on the intricately intertwined construction of their technological knowledge and content knowledge. It will also, in the words of Mishra and Koehler (2006), through scholarship and research, provide insights and deep understandings into “the nature and development of teacher knowledge” (p. 1045) of gamification. This would be considered as the academics’ pedagogical knowledge of gamification, which would inform us the pertinent “deep knowledge about the processes and practices or methods of teaching and learning and how it encompasses, among other things, overall educational purposes, values, and aims” (Mishra & Koehler, 2006, p. 1026) of gamification in HE. It is important that academics have deep pedagogical knowledge of gamification as it would facilitate their understanding of how “students construct knowledge, acquire skills, and develop habits of mind and positive dispositions toward learning” through gamification (Mishra & Koehler, 2006, p. 1027). Therefore, academics’ pedagogical knowledge of gamification requires them to have an “understanding of cognitive, social, and developmental theories of learning and how they apply to students in their classroom” (Mishra & Koehler, 2006, p. 1027).

Pedagogical technological content knowledge. The three circles, content, pedagogy, and technology, overlap to lead to four more kinds of interrelated knowledge. (Mishra & Koehler, 2006, p. 1025)

In the similar vein to the TPCK framework, Churchill (2006) emphasized the importance of teachers and instructors developing their ‘private theories’ related to teaching using technology i.e. how academics “make decisions and take actions” (p. 559) in the planning, implementing and assessing gamification that is based, guided and developed by their own reflections on their: (i) personal and meaningful observations in classrooms; (ii) engagement and interactions with, and of students and, (iii) instructional decision making and its effectiveness. By doing so, academics would be able to reason and make better decisions regarding the means of implementing gamification. The ability to make such critical decisions based on academics’ reasoning and pedagogical knowledge is the very core of their understanding that would lead to the appropriate and desired changes “in teaching and learning towards student-centered practices” (Churchill, 2006, p. 575), and in this case, gamification. Molenaar and van Schaik (2017) place intense emphasis on the importance of the abilities and practices of teachers in making pedagogical decisions when using educational technology that would surely impact the learning environment and teaching experiences. Thus, the TPCK framework and the development of private theories (as well as other related frameworks and theories) are parts of many efforts to enhance and enrich teaching in HE and to effectively support students’ learning via gamification. In line with this, many researchers, experts, and educators believe and imply that knowing, identifying, and understanding categories or criteria of effective teaching may scaffold effective teaching. It would then promote better construction of learning in future in the context of HE.

In understanding academics’ practices of gamification, Devlin and Samarawickrema’s (2010) criteria of teaching in HE, which consists of five criteria, are used in the development of the research instruments: Criterion 1 – ‘Approaches to teaching that influence, motivate and inspire students to learn’; Criterion 2 – ‘Development of curricula and resources that reflect a command of the field’; Criterion 3 – ‘Approaches to assessment and feedback that foster independent learning’; Criterion 4 – ‘Respect and support for the development of students as individuals’ and; Criterion 5 – ‘Scholarly activities that have influenced and enhanced learning and teaching”. These five criteria, functioning in tandem with each other, facilitate and establish the standard and quality of teaching and learning in HE. In doing so, the criteria ought to incorporate the “skills and practices of effective teachers and the how teaching should be practised within multiple, overlapping contexts” (Devlin & Samarawickrema, 2010, p. 122). However, these criteria should be constantly monitored, reviewed, and renewed as challenges and changes in HE is continuous and unpredictable, especially in terms of economies, political systems, and social structures (Enders, 2004), marketization of HE (Zhang & O'Halloran, 2013) and global disasters and pandemics, like COVID-19 (Crawford et al., 2020), among others.

The interplay between TPACK, personal theory of academics and criteria of teaching in HE, as explained above, forms the conceptual framework that is used as the base to navigate the current study. TPACK frames academics’ practices of gamification, personal theories to outline and identify academics’ pedagogical reasoning for gamification. While the five criteria of teaching in HE are used as the standard and context for academics in using gamification for teaching and learning.

4 Methods

An explanatory-sequential mixed-methods design was employed in this study (Creswell & Clark, 2000), whereby the quantitative data (obtained using a questionnaire) provided a general picture of the research problem. Qualitative data (open-ended items and interviews) were used to clarify, refine, extend and explain the general picture. Both quantitative and qualitative data are the primary focus of this study.

4.1 Context, participants and sampling technique

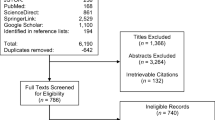

This study was carried out with academics in University A, which is one of the leading research universities in Malaysia. The university offers academic programs (both undergraduate and postgraduates) in the fields of social sciences and sciences. Convenience sampling was employed in this study to select the participants based on accessibility and proximity (Creswell 2007). A questionnaire was developed using Google Forms and its URL link was shared with all academic staff (n = 2126) of the university via the university’s official internal email circulation with an accompanying message (see Supplementary Information Appendix A). This message was constructed in such a manner that only academics who were using gamification in their teaching and learning process would need to respond. Nevertheless, we were aware that there could be academics who would still respond to the survey despite their non-inclusion of gamification in their teaching and learning. Hence, we included two items – ‘heard of the term “gamification” and ‘used gamification for my courses’, particularly if they respond to the items with ‘Never’. As a result, a total of 97 academics answered the questionnaire.

An email was sent to all the 97 academics whereby the researchers enquired if they would be interested in being interviewed to further understand their practices, reasons, and challenges. More than half of samples agreed but we only selected 25 academics, who reflected the diverse fields of university, the gender proportions (9 females and 16 males) and age range (35 – 50 years) (Fig. 2). Prior to the interview, the academics were briefed on the confidentiality of the interviews and that they were not, in any way, assessed or evaluated on their teaching and learning activities. Each interview lasted between 30 to 45 min. A total of 97 academics participated in this study with the composition of 39 males (40.2%) and 58 females (59.8%), and an average age of 44.4 years (a range of 29 to 62 years). The samples’ average teaching experience is 12.49 years, with a range of 1 to 43 years. Most of the academics are experienced with at least 10 years of teaching experience (n = 59, 60.8%) while the remaining (n = 38, 39.2%) have lesser.

4.2 Instrument and data analysis

The questionnaire contained two parts – a 5-level Likert scale survey and two open-ended items. The in-depth interview had six main items. Both instruments were validated by two researchers in the field of educational technology—one from the same university as the researchers and the other from a different local public university. They agreed that all the items in the respective constructs of the questionnaire are valid and reflect the notion of ‘practices’, ‘benefits’, and ‘challenges’ that were measured in the questionnaire. They also agreed that the items are easily understood as they are direct and simple (in terms of meaning of the terms/ words/ phrases/ sentences), and do not include double barrel items. The questionnaire in this study consisted of four sections. Section A solicited demographic information of the academics i.e., gender, age, teaching experience and faculty/department. Section B comprised 15 items in a construct (or an aspect that were measured) on academics’ practices of gamification (in terms of frequency). It used a 5-level Likert scales of ‘Never’ to ‘Always’, had a very high reliability (0.939).

Section C addressed the second research question i.e. ‘Why do academics integrate gamification in their courses?’ This construct had 18 items that used a 5-level Likert scale of ‘Not important’ to ‘Very Important’, with a very high reliability (0.978). Section D contained two open-ended items that queried academics’ practices, experiences and challenges faced in implementing gamification in teaching and learning, especially in terms of technology, pedagogy, and content. All the items in the three main constructs i.e., Sections B, C and D were developed by the researchers based on elements of five criteria of practices of effective teaching in HE proposed by Devlin and Samarawickrema (2010) and elements/constructs by Mishra and Koehler (2006). These criteria and elements were integrated into the development of items of the questionnaire and aligned to the various aspects of gamification and tenets of teaching and enhancing the academics’ knowledge and skills of gamification. As for the development of interview items, elements/constructs of TPCK and the three research questions were used as guidelines. Table 1 exemplifies how the items in the questionnaire and interviews were derived and developed.

For example, Row 1 of Table 1, which is ‘Practices (SECTION B)’, shows how the 14 items in Section B of the questionnaire (See Supplementary Information Appendix B), were derived from both the literature (Devlin & Samarawickrema, 2010) and theory (The TPACK model by Mishra & Koehler, 2006). For this particular construct (i.e., Practices), Criterion 5 from (Devlin & Samarawickrema, 2010) and the element of ‘Content Knowledge’ from (TPACK model) were integrated, referred to, and utilized in developing all the 14 items in Section B of the questionnaire [Column 2, Row 1]. To illustrate the process, the two elements of Criterion 5 i.e. (i) ‘Participating in and contributing to professional activities related to learning and teaching’, and (ii) ‘Conducting and publishing research related to teaching’, and the element of ‘Content Knowledge’ i.e., ‘teachers’ knowledge of the subject’ were integrated. From this amalgamation, we derived items that reflected the academics’: (i) knowledge and practices of professional activities related to gamification as a pedagogy for teaching and learning in HE (Items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6), and (ii) practices of research and publication related to gamification as a pedagogy for teaching and learning in HE (Items 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14). Items 1 – 14 are listed in Column 3, Row 1. The above principle and process were applied to the development of items for the other sections (Sections C and D) in the questionnaire.

For the analysis of the demographic data, frequency and percentages were used; whereas for the description of items in the constructs, frequencies, percentages, mean scores and standard deviations were employed to describe the academics pedagogical understandings, practices and reasoning. As for the open-ended item and interview items, the academics’ views were categorized into emerging themes and analyzed using situation and activity coding strategies (Bogdan et al., 1992). The situation codes were assigned to units of data that described how the academics defined and perceived gamification for teaching and learning for specific situations. The activity codes were assigned to units of data that described the academics regularly occurring behavior, especially in reasoning and practicing gamification for teaching and learning (Bogdan et al., 1992). Table 2, using actual data from the interview, depicts how the situation codes and activity codes were used to derive one of the themes. This procedure was used to develop other related themes that would support the quantitative data.

The qualitative data from the open-ended items (Section D) and interview items were used to support and give meaning to the quantitative data analysis. To ensure systematic analysis and presentation of academic’s excerpts, each academic was coded L1, L2, L3…L97, respectively and their comments, views and opinions were expressed as the excerpts were stated by the academics and identified by their respective codes. For example, ‘L4i’ would refer to data obtained from the fourth academic in the study via the in-depth interview, while ‘L16oe’ would refer to data obtained from the sixteenth academic via the open-ended items. The complex and rich nature of the qualitative data means that some excerpts may imply and include more than one theme, and, at times, the themes may be tangled and intertwined with one another in an excerpt. Hence, two researchers (specifically Author 1 and Author 2 of this study) were engaged in an independent and separate analysis of data in identifying the emerging themes. Miles and Huberman’s inter-rater reliability was conducted to assess the level of agreement and consistency of the themes. An agreement of 80% was reached, while the remaining 20% of the differing opinions were resolved by selecting the themes that directly reflected and supported the items in the two constructs.

5 Findings

The following section presents the findings and discussion according to the key constructs of the study, which are also aligned to the research questions.

5.1 Academics’ practices of gamification

The academics in this study teach various subjects, ranging from pure sciences to social sciences, in various departments/schools, centers of excellence and service providers at the university (see Table 3). This kind of distribution implies that the findings of this study could be relevant and generalized to academics from different areas of specialization. For the construct of academics’ practices of gamification using technology, the responses from the respondents were first tabulated according to frequency and percentage as shown in Table 4. Generally, it can be noted that most of the responses fall under the categories of “never” and “seldom”.

Table 5 summarizes the findings according to mean and standard deviation (SD) scores for clearer comparison.

Based on these findings, it can be summarized that academics in this study are still inexperienced and new to the concept of gamification and its related practices. Similarly, the scholarly activities and research narratives related to gamification are far from encouraging. For example, only 16 (16.6%) academics have published at least one article so far (Mean = 3.00, SD = 1.03) and only 19 (19.5%) academics have presented at least one paper on gamification at conferences (Mean = 2.89, SD = 0.937). Other scholarly activities such as reading, discussing, and attending training related to gamification are not encouraging as well, with all these items scoring mean scores that are less than 2.50. However, in terms of teaching, more than half of the academics in this study (n = 54, 56.2%,) have utilized gamification at least once in an academic year in their courses (Mean = 3.04, SD = 0.990).

While we have emphasized in the initial email that the survey is only intended for those who have used gamification for teaching and learning, we still received responses from 42 academics who have not used it at all. Also, 10 academics have not even heard of the term ‘gamification’ prior to this study (See Table 4). Though the two items functioned as a sieve to identify practicing and non-practicing academics in terms of gamification use, we included these data in this paper. The main reason is that some of those respondents volunteered for the interview and contributed meaningful insights into the challenges of integrating gamification in teaching and learning. It also indicates their curiosity about gamification and willingness to offer their views on it.

Qualitative data from the interviews indicate that the academics learned the term ‘gamification’ in professional development courses organized by the university (L20i, L26i, L31i) as well as from their peer networks (L20i, L26i). Social media and academic events such as conferences are also sources of knowledge of gamification for academics. For example, L31i mentioned ‘TUTOR’, a popular social media in the United States and Europe, whereas L25i says, “I heard it when I went for a competition on innovation and education in 2017. It was a simple gamification for Math students in high school”.

Most of the academics are aware of the term gamification in this study, but 43.8% (n = 42) have not utilized it in their teaching as they are concerned with time factor especially when “more preparation is needed in terms of execution and reward” (L4oe) and insufficient time “to finish one lecture” (L24oe). L9oe emphasizes that too much time and effort is taken to “teach a simple concept” and the fact that “other methods may achieve the same objectives with less time and effort”. Furthermore, according to some academics, the gamification pedagogy may not be suited to certain subjects and contents, as well as the level of education/degree they are teaching:

Some physics concepts in some of the games that I have seen are wrong (L9oe)

Maybe difficult to teach clinical related topics when the student need to be taught and tested on certain skills such as physical examination, identification of drugs related problems and other medicines related information that need to be individualized (L3i)

Not relevant to Chemistry. My course is related to drawing structures. For example, molecule structures. It is suitable for high school, rather than adults (L32i)

5.2 Academics' pedagogical considerations/ reasoning for gamification

The findings on the reasons or purposes for integrating gamification in their teaching and learning are shown in Table 6.

From the tabulated frequencies and percentages, it can be noted that the academics are aware of the importance of integrating gamification in their teaching and learning using technology. Table 7 further summarises the findings according to overall mean scores and SD values.

The academics in this study use gamification in their teaching mainly to motivate their students’ learning (Mean = 3.85; SD = 1.064) where 70.1% (n = 68) of the academics deem gamification as an important pedagogy and only 4.1% (n = 4) saying gamification is not important to motivate students. The other four items that the academics feel are important reasons for them to integrate gamification into their teaching are encouraging students’ critical thinking (Mean = 3.77; SD = 1.075), encouraging students’ creativity (Mean = 3.74; SD = 1.121), ensuring students interact with the content (Mean = 3.73; SD = 1.046) and engaging students in solving problems (Mean = 3.71; SD = 1.070).

Qualitative data from the open-ended-items and interviews support the quantitative data. The qualitative data provide a detailed account of pedagogical considerations behind the integration of gamification into their teaching under the following five themes: i) Motivating students’ learning; (ii) Facilitating thinking skills and solving problem; (iii) Engaging students’ learning; (iv) Facilitating interactions and (v) Achieving specific teaching and learning goals.

5.2.1 Motivating students’ learning

Academics in this study believe that gamification shows capacity to motivate, develop, and optimize students’ learning. It plays a part as a remedy when there is a decline in motivation (L11i, L16i, L26i). According to L20oe, lessons that utilize gamification involve the use of “interesting teaching aids” that motivate the student to attend classes. On the contrary, this is not the case when “lecture slides are used” (L15oe). Once motivated “it is easier for students to understand hard concepts” (P5oe), which “improves their understanding on certain topics” (L3oe). The academics believe that gamification would fuel and sustain their students’ motivation level in the learning process by evoking their “interest in learning” and retaining that interest by delivering “the appropriate content to them” (L6oe). This is usually the case when gamification is used as “a tool for motivation” for the “weaker group” and as a platform of “content delivery” for the “smart group” (L71i).

5.2.2 Facilitating thinking skills and solving problems

Most of the academics also utilize gamification as a platform to facilitate students’ creative and critical thinking skills, and to nurture their problem-solving skills (for example, L3oe, L34oe, L39oe, L50oe). L45i sees gamification as a “brainstorming” device that, according to L2i, is an important element “in cultivating critical thinking and problem-solving skills”. In such situations, students become “very participative” when they are solving the problems and completing the tasks collaboratively. This is because “the students will try to help their peers while completing the tasks” (L25oe) “with a shared mental model of achieving the outcomes but with still enough rooms for diversity in opinions/ideas” (L7oe).

5.2.3 Engaging students’ learning

This theme is derived based on the academics’ various approaches and perspectives of engaging students in meaningful learning using gamification. The academics emphasize on the fun and interactive learning that gamification propagates—“active learning”(L1oe) that allows “knowledge absorption” (L11oe) and “helps reinforce students’ learning and eliminates boredom” (L27oe) by giving them “the opportunity to see the real-world applications” (L11oe). These keep the students focused (L29oe). They are also empowered and entrenched in deep learning (L9oe), which results in the academics achieving the “objectives of the lesson” as “students are able to remember the content taught” (L12oe). All the above are transpired collaboratively through networking (L9oe) and as a community of practice, whereby the students are “Gen Z” (L31oe), active gamers (L11i, L69oe) and are very much “tech-savvy” (L16i). According to L31i, “students are very much engaged in learning” if “it is (integrated with) technology game-based” on the students’ smartphones.

The above excerpts explain the quantitative data and encapsulate the overall means scores of items that reflect students’ engagement such as, ‘engaging students in completing tasks’, ‘engage in solving problems’ and ‘engaging in completing projects’.

5.2.4 Facilitating interactions

From the quantitative data, three types of interactions are highlighted by the academics for reasons of planning gamification—peer interaction, student–teacher interaction, and student-content interaction. These were also described by the academics in the qualitative data. L24i says the gamification is used to enhance class interaction between “lecturer and students” (L18oe), whereby the “students will learn faster” and “will show more interest in class” and that “engaging with them will be easier” as their teacher. As for L2oe, these interactions are “most important”. The “interaction between groups of students” are crucially important because the students would heighten “their enthusiasm to complete a task and increase understanding”. L26oe points out the interaction between the students and the content to be learned using gamification gives “students a different perspective on how certain content/skills are to be acquired and allow students to engage in a meaningful task”. L4oe concurs, “Gamification is vital to motivate students to interact with the course instructors. Gamification can be used to explain tough concepts in a more engaging and interesting way”.

5.2.5 Achieving specific teaching and learning goals

Many academics in this study agree that gamification may effectively achieve specific teaching and learning goals. It is used as an ice-breaking session (L13i, L14oe), as a set induction (L45i), as a teaching aid (L840e), or as a brainstorming session (L45i). L4i describes gamification as a tool to be used at the “beginning stage” with the aim to “trigger some concepts” because once the concepts are unraveled, “the students would be able to comprehend the lesson easily”. It may also be valuable for learning at later stages of lessons, specifically for “retention” of knowledge, ideas, and concepts (L38oe), reinforcement of learning (L35oe, L61i) and assessment (L12oe). It could be used to test students’ “knowledge before starting a lesson” and after a lesson (L18i, L30i) and also to assess students’ understanding (L71oe, L85oe) and “students' comprehension on course content” (L19oe). These excerpts further explicate this aspect of the theme,

It will be used after lecture. Reinforcement. Also for reinforcement and assessment. Gamification cannot be used for the whole course I am teaching English, it cannot be the main focus (L16i)

For recapping a lesson, I test students on what they have learned. I will ask students to create their own Kahoot. They have to create their question and answers. Students can learn from each other (L31i)

During the last five minutes of class, students reflect on the lesson and write down what they’ve learned (L20i)

Another critical reasoning of gamification is the diversification of teaching and learning methods (L16oe, L38oe, L28i) in which,

… students can learn via holistic approaches and not just depend on one or two methods; This approach allow student to explore some areas of my subject that hard to be explained using words or pictures, exp, physiological changes in our body, the ecosystem of deep ocean etc. (L16oe).

Using gamification is a way of varying teaching methods by the academics, as the students “learn in a more effective way than just memorizing” (L62oe). All these ‘varied’ methods of gamification are carried out with the intention of ensuring the teaching and learning sessions would be interesting (L3oe, L14oe, L22oe, L25i) and not boring (L31oe, L35oe, L5i) in an environment that is less stressed (L78oe) and relaxed (L14oe, L27i).

5.3 Challenges in integrating gamification

In integrating gamification, the academics in this study faced the following challenges and difficulties. First is the time factor, which many academics have expressed that integration of gamification requires a lot of time for preparation (for example, L4oe, L23oe, L26oe, L30i). The teachers need to be “clear of what needs to be done” (L30i) and how it will be implemented (L4oe), especially in teaching certain concepts.

As indicated earlier in the findings of academics’ practices of gamification, another huge ‘challenge’ mentioned by the academics is the suitability of gamification in HE.

In my area [pharmacy] the need to know problems related to medication. How can I put it as a game. It is only suitable to acquire knowledge but not for higher order thinking. maybe will use it for introduction (L31i)

Not relevant to Chemistry. My course is related to drawing structures. For example, molecule structures. It is suitable for high school, rather than adults (L32i)

It never works for practicum and projects for numerical questions, derivation of equation (L41i).

Usability and accessibility of technology are also stated by some of the academics, (L9oe, L14oe, L15oe, L51i). L14oe explicates,

The use of technology…not all students have access to device and have their own data package. Need to depend on limited facility on campus low Wi-Fi in campus and lecture halls without Wi-Fi access at all due to the location. generation gaps where some academics are usually reluctant to venture technology based teaching and learning activities.

6 Discussion

6.1 Academics’ practices of gamification

Though many of the academics in the study are aware of the gamification concept and have used it for teaching, they are not able to extend and enrich their knowledge and skills of gamification through other related scholarly activities. These knowledge and skills are important in the delivery of effective teaching. Such activities would contribute to the academics’ “cutting edge of their discipline” and “awareness of the international perspectives in their field” (Marsh, 2007 as cited in Devlin & Samarawickrema, 2010, p. 118). If equipped with these, academics should be able to plan teaching in HE (using gamification) that motivates and engages students in a more meaningful and impactful learning. This will lead to significant quality changes for the specific contexts of teaching (Devlin & Samarawickrema, 2010).

The reasons given by academics for not integrating gamification (from the qualitative data), to us, sound more like excuses that reflect and demonstrate their lack of understanding and synergic application of TPCK. The main aim of gamification is not so much on the subject matter, but rather to create real-world environments, which supports learning and problem solving (Kim et al., 2018). The aim is to alter or change learners’ behaviors and attitudes, culminating in students’ positive learning outcomes (Dreimane, 2019). Based on their practices of gamification, academics in this study appear to be lacking related competencies.

Apart from TPCK, Nousiainen et al. (2018) discover that collaborative and creative competencies are also needed by academics in planning, organizing, implementing, and assessing effective gamification for learning. Collaboration is important because it nurtures novel approaches and facilitates innovative teaching. Ultimately, it engages “teachers in practicing new teaching methods and a common vision” that encourages fresh approaches to gamification (Nousiainen et al., 2018, p. 94). Such collaborative practices may well result in academics developing renewed connections between existing ideas or concepts, and facilitating them to generate new knowledge, ideas and, concepts (Dillon et al., 2013) related to gamification. Quantitative data from this study, however, show a scarcity of collaborative practices among the academics in the implementation of gamification.

The academics’ responses in the interviews also imply their lack of creativity in planning and conceptualizing gamification for teaching and learning. Creativity is crucial in gamification as academics would be able to “express a playful stance of exploring, improvising and innovating”, be motivated to learn and be more inquisitive, especially in planning and conducting gamification (Nousiainen et al., 2018, p. 94). We believe aspects of collaboration and creativity are interlaced and intertwined with each other in promulgating an innovative gamified pedagogy, just as suggested by the TPCK framework.

Based on the findings pertinent to the academics’ practices, we can conclude that in this study, most of them, (i) only have basic knowledge and skills of gamification pedagogy, (ii) lack creativity in implementing gamification for teaching and learning and, (iii) do not integrate collaborative practices when implementing gamification pedagogy.

6.2 Academics' pedagogical considerations/ reasoning for gamification

An overall analysis of data from Tables 5 and 6 indicate that at least 80% of the academics in this study state that all the 18 items are ‘moderately important’ pedagogical considerations or reasons they have cogitated in planning and implementing gamification into their teaching. The qualitative data indicate five main pedagogical considerations behind the integration of gamification into their teaching:

-

i)

Motivating students’ learning

The item ‘motivate students’ learning’ is the highest mean score and well-supported and clarified by the academics in the interview. The academics’ pedagogical reasoning in introducing gamification into their teaching is obvious – to motivate and stimulate students’ interests for learning and facilitate their comprehension. Hassan et al. (2019) explain that such gamification strategy i.e., selecting elements and activities according to students’ learning dimensions could significantly increase their motivation level as it fulfils the students’ “psychological desires of self-determination and competition” (p. 2). And when students’ motivation levels are heightened, in a gamification environment, students “can spontaneously and willingly achieve learning goals” (Hung et al., 2019, p. 1032).

-

ii)

Facilitating thinking skills and solving problem

Both quantitative and qualitative data illustrate that academics utilize gamification as a platform to facilitate students’ creative and critical thinking skills and to nurture their problem-solving skills. Such outcomes are plausible due to technological affordances and academics’ practices that “work in concert to provide layers of effective learning experiences” (Abrams & Walsh, 2014, p. 57). According to Abrams and Walsh (2014), these effective learning transpire when students’ own knowledge, the complexity and collaborative nature of the given tasks, in amalgamation with the feedback provided by academics, drive and guide students in attaining problem-solving and critical thinking skills.

Abrams and Walsh’s (2014) study testifies to gamification and its relevance and application of the TPCK model. The outcome of their study calls for a learning environment that engages students and academics “to explore technologies in relationship to subject matter in authentic contexts” (Mishra & Koehler, 2006, p. 1045). Gamification could be an authentic context of learning, whereby students are the focus of teaching, are actively engaged and are cognitively stimulated (Tan et al., 2022). The academics grasp this power of gamification and utilize this knowledge to stimulate the minds of their learners and energize their thinking skills. They also use it as one of the key pillars of pedagogical reasoning in planning and integrating gamification into their teaching and learning.

-

iii)

Engaging students’ learning

The kinds of student engagement and community building mentioned by the respondents are enhanced when interactivity and collaboration are used as the guiding principles in supporting the students’ learning (Klemke et al., 2018). This is because, from the perspective of TPCK, the gamification pedagogy engaged the students in the activities that “compelled” them to “seriously study technology, education, the interface between the two, and the social dynamics of working with others” (Mishra & Koehler, 2006, p. 1038). This is a form of varying learning tasks that can engage students for meaningful learning experiences that academics should plan and implement. This is, without a doubt, one of the key criteria for effective teaching and learning in an evolving HE settings (Devlin & Samarawickrema, 2010).

According to Reeve and Tseng (2011), previous research on gamification has rarely discussed student engagement, especially the ones that are based on four types of learning engagement—emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and agentic engagement. Considering this, the present research contributes to engagement theory through the implementation of gamified learning and formative assessment. In this study, the academics emphasize the importance of ensuring students’ engagement in learning via gamification as a way of internalizing, reinforcing, and applying knowledge that has been learned. Therefore, ‘engaging students’ in gamification pedagogy – whether it is in terms of learners’ emotions, behaviours, cognitions or agentic – is the academics’ key consideration to ensure the attainment of the stipulated learning objectives and outcomes.

-

iv)

Facilitating interactions

Similar to academics in this study who emphasized the importance of facilitating interactions, Devlin and Samarawickrema (2010) advocate the need for academics to continuously learn and apply new skills in order to “familiarize themselves with new ways of interacting and communicating with students” (p. 119). And when academics design gamification for teaching and learning, they demonstrate the skills learned. This process reflects the “tremendous growth in their sensitivity to the complex interactions among content, pedagogy, and technology, thus developing their TPCK” (Mishra & Koehler, 2006, p. 1046). In addition to TPCK, the interaction between students and the contents emerges as a critical element of interaction in gamified pedagogy, whereby students are engaged via the exploration of content. This allows them “to engage in the learning process through reinforcements and practice” (Shroff et al., 2020, p. 107).

To summarize, the academics in this study identify and are aware of three types of interaction – peer interaction (student–student), student–teacher interaction and student-content interaction – that are important pedagogical considerations in implementing gamification pedagogy in HE. These interactions are necessary for the effective instructions and delivery (by academics), as well as understanding, grasping, and learning of concepts, ideas, and knowledge (by students).

-

xxii)

Achieving specific teaching and learning goals

Both quantitative and qualitative data stress the importance of achieving teaching and learning goals using gamification. This is also underscored in the framework of TPCK that necessitate teachers to “engage with the affordances and constraints of particular technologies to creatively repurpose these technologies to meet specific pedagogical goals of specific content areas” (Mishra & Koehler, 2006, p. 1032). Academics should embrace and practice this approach to teaching since learners in the digital age are fluent, flexible, and intense technology users, who expect their learning needs are met according to the environment they are engaged in (Shroff et al., 2020). The application of gamified pedagogy, hence, is two pronged. First is experimenting and innovating with new teaching ideas and approaches (Martí-Parreño et al., 2016) with the aim of achieving specific teaching goals. Second, simultaneously facilitating students’ abilities to attain and demonstrate certain learning opportunities and goals and to utilize solutions that allow for learning in a technologically supported environment (Shroff et al., 2020). These are reflected and emphasized by the academics in the interviews. The academics view gamification as one of the many approaches or methodologies to creatively teach students in HE, whilst achieving the intended learning outcomes using technology.

6.3 Challenges in integrating gamification

The challenges shared by the respondents are surmountable. In fact, we believe that with proper comprehension of gamification and its pedagogy, and TPCK and related skills, academics would not regard them as challenges but rather as elements or criteria to be considered when planning and preparing gamification. For instance, the time factor and the suitability of gamification. The amount of time taken in planning and preparing gamification is not a waste of time, but a necessary measure so that the implementation is effectively managed and fruitful (King-Sears & Evmenova, 2007). It is also a strong determiner in influencing academics’ uses of technology for teaching and learning (Darling-Hammond, 1997).

As for suitability of integrating gamification, academics should be examining and developing the understanding of the real purposes of using gamification (using technology). Once such understanding is reified, they can ensure it supplements the predetermined learning outcomes and use it for specific aims of learning (King-Sears & Evmenova, 2007). These, in amalgamation, could burgeon into academics’ own private theories of gamification that may be used for designing, planning and, implementing an innovative gamification pedagogy and assessing it accordingly (Churchill, 2006). Therefore, in addressing the suitability of gamification, academics should be asking ‘How’ and ‘Why’ the need to integrate, and not so much if one should or should not integrate i.e. ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ questions. The ‘challenges’ faced are in fact pedagogical considerations that the academics have ruminated to ensure effective teaching and learning using the gamification pedagogy. They may not be actual problems that they need to resolve and surmount (though they may appear so to the academics).

7 Limitations of the study

Indeed, this study has offered a different yet pertinent perspective of academics in HE when adopting gamification for teaching and learning purposes with the assistance of teaching. It is however, not without acknowledged limitations. As convenience sampling was used in this study, the findings from this relatively small sample size do not represent the population of HE academics in Malaysia let alone in other parts of the world. Hence, we are not able to make generalization of academics’ practices and pedagogical reasoning to other learning environments. Nevertheless, this does not mean the findings cannot be used to understand problems and challenges related to the use of gamification in teaching and learning in HE and to develop strategies to surmount those problems and challenges.

Also, the study was intended to gauge the initial framing of gamification adoption among academics without going deeper by including other correlational variables. These limitations, nevertheless, could pave the way for future studies to consider, particularly by including a broader range of HE institutions in Malaysia and other Southeast Asian countries.

8 Implications of the study

Based on the findings of the study, one of the implications is that academics should understand and accept that teaching in HE is not solely about teaching and learning. It is also about the scholarship of teaching and learning, in which academics formulate research questions and pursue scientific and systematic inquiries in collaboration with peers and students. The aims of these measures are to improve their teaching practice, enrich students’ learning, and share the findings with the public. Institutions of HE should seriously deliberate on a myriad of strategies on the authentic acculturation of academics’ practices of scholarship of teaching and learning at the university level. It should be extended further to the national and international stages once the assimilation to this culture is strengthened. Whether it is gamified pedagogy, or any other emerging pedagogies, academics should be trained and readied to engage in professional development activities and programs. This initiative would engage and energize them, connect and develop special interest groups, foster collaboration, advocate scholarship of teaching and learning, and integrate individuals’ interests and HE institutions’ practices and policies (Simmons & Taylor, 2019).

The question is, how should HE undertake such a process? This could be done based on the data of this study that are framed within Churchill’s (2006) work on teachers’ development of private theories and Devlin and Samarawickrema’s (2010) work on effective teaching and learning. Administrators, and training departments in HE should consider the five-phase ‘Model of Developing Private Pedagogical Theory for Gamification’ (Fig. 3).

Using the model, the academics are well equipped with knowledge and understanding of TPCK and effective teaching. They are then guided on determining the aims of integrating gamification in their respective courses. This facilitation needs to be aided by a fluid strategy where involvement of both academics and students in every phase of teaching and learning and assessment using gamification is emphasized in terms of collaboration and creativity. The final cycle in the model is the ‘share and reflect’ phase where the academics are encouraged to practice scholarly activities (such as the ones listed in the questionnaire of this study) related to their planning and experiences of implementing gamification and reflect on these practices. Churchill (2006) postulates that these processes would engage the academics to “identify the theories that mediate their own design” and thus, would be able to make better decisions related to the changes they intend to make (p. 575). This model could also be adapted for implementing other pedagogies, by appropriating and presenting the relevant theories in the first phase of preparation.

As for the individual academics, the concept of pedagogical reasoning or consideration, as far as gamification is concerned, should be understood not from a narrow angle but from an open, wide, and complex one. Though five seemingly separate themes have emerged from this study, they are connected to each other, depicting a multi-directional relationship between the themes (see Fig. 4). For instance, an academic may plan a gamification lesson with the sole aim of ‘facilitating interaction’ but it could lead to motivating the students in the process and facilitating the students’ thinking and solving problems skills, which then could motivate them even further as they are being led into different zones and experiences of meaningful learning. The model allows the academics to be aware that it is both essential and fundamental to plan and navigate gamified teaching and learning as a very intricate and multiplex process that has the potential to achieve multiple learning outcomes, depending how it is planned, objectified, and implemented. Ultimately, academics should realize that gamification is more than just playing while learning.

These proposed models are conceptualized based on the synthesized findings gathered from this study. Although not definitive, these models could potentially assist academics in taking the initial steps in examining their practices and purposes in integrating gamification. Future studies could also experiment with them and investigate thoroughly the outcomes. Also, more studies on academics’ pedagogical reasoning in different contexts may enlighten us with different comprehension of academics’ practices in using gamification and the influence of sociological (including cultural), technological and philosophical factors.

9 Conclusion

The study attempts to understand academics’ practices, pedagogical understandings or reasonings of gamification, which is an area with little evidence, as indicated by literature. The research gap of pedagogical gamification in HE is addressed by the five key findings described in Fig. 4. Nevertheless, more studies in different contexts and using different methods are needed to have a thorough and deep understanding of academics’ pedagogical reasoning of gamification in HE.

The study also identified the challenges faced by academics in planning and integrating gamification into their teaching and learning. Quantitative and qualitative findings indicate that while most academics in this study know and understand gamification’s potential benefits in terms of students’ learning and development, there are areas of concerns that need to be reviewed. For instance, academics in this study do not seem to understand that gamification is not a method to substitute them as the teacher or replace other forms of teaching and learning activities but rather a method to facilitate, enhance and enrich teaching and learning (Brophy, 2015; Namoco, 2021).

Some of the academics do not seem to grasp that gamification is certainly not a one-size-fits-all pedagogy as different students and groups of students and different subjects and topics require different gamification activities and tasks and different ways of approaching and implementing the gamification pedagogy for different purposes. This is the kind of cognizance and interpretation of the gamified pedagogy that academics should initiate, develop, and eventually master and practice. Such academics would embrace Strmečki et al.’s (2015) logical postulation that not all students need motivation and like to play games or compete with others, and therefore, the students’ “learning habits” must be deliberated when a gamified pedagogy is planned (p. 1109).

In terms of practice, the academics were not very eager with regards to their scholarly activities, such as collaborating, researching, presenting findings and publishing on gamification. These scholarly activities are necessary and needed by the academics for generating new, fresh, innovative and creative ideas, constructing new pedagogical knowledge and developing competencies required for gamification (Nousiainen et al., 2018). Devlin and Samarawickrema (2010) also underscore the magnitude of university teaching and how it should mirror scholarly and academic rigor that embody “extensive professional skills and high levels of disciplinary and other contextual expertise” (p. 111). Academics with such characters would be able to teach effectively using gamified pedagogy that contributes to quality learning.

As a concluding remark, we would like to interpolate and relate Shulman’s (1987) argument of teacher education’s goal to what we believe, based on the findings of this study, how the integration of gamification should be regarded and embraced by academics in HE:

...it is not to indoctrinate or train teachers to behave in prescribed ways, but to educate teachers to reason soundly about their teaching as well as to perform skillfully. Sound reasoning requires both a process of thinking about what they are doing and an adequate base of facts, principles and experiences from which to reason. Teachers must learn to use their knowledge base to provide the grounds for choices and action… Good teaching is not only effective behaviorally, but must also reset on a foundation of adequately grounded premises. (p. 13)

This study, we hope, would straighten some of the misconceptions of integrating gamification in HE, as well as cajoling academics in engaging in scholarship activities as a way of improving teaching and learning using gamification with sound reasoning. Identifying existing private theories and further developing new ones based on practices and established theories, and supported and enriched by scholarly pursuits, is a form of “a foundation of adequately grounded premises” (Shulman, 1987, p. 13).

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available as the authors do not wish to share the data as this may breach participant confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abrams, S. S., & Walsh, S. (2014). Gamified vocabulary. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 58(1), 49–58.

Bogdan, R., & Biklen, S. (1992). Qualitative research for education. Allyn & Bacon.

Boyle, E. A., Hainey, T., Connolly, T. M., Gray, G., Earp, J., Ott, M., ... & Pereira, J. (2016). An update to the systematic literature review of empirical evidence of the impacts and outcomes of computer games and serious games. Computers & Education, 94, 178–192.

Brophy, K. P. (2015). Gamification and mobile teaching and learning. In Y. Zhang (Ed.), Handbook of mobile teaching and learning (pp. 91–105). Springer.

Chans, G. M., & Portuguez-Castro, M. (2021). Gamification as a strategy to increase motivation and engagement in higher education chemistry students. Computers, 10(10), 132.

Churchill, D. (2006). Teachers’ private theories and their design of technology-based learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 37(4), 559–576.

Crawford, J., Butler-Henderson, K., Rudolph, J., & Glowatz, M. (2020). COVID-19: 20 Countries’ higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. Journal of Applied Teaching and Learning (JALT), 3(1), 9–28.

Creswell, J., & Clark, V. (2000). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 2nd edn. Sage Publications, London, UK

Darling-Hammond, L. (1997). Doing what matters most: Investing in quality teaching. National Commission on Teaching & America’s Future.

Devlin, M., & Samarawickrema, G. (2010). The criteria of effective teaching in a changing higher education context. Higher Education Research & Development, 29(2), 111–124.

Dichev, C., & Dicheva, D. (2017). Gamifying education: What is known, what is believed and what remains uncertain: A critical review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14(9), 1–36.

Dillon, P., Wang, R. L., Vesisenaho, M., Valtonen, T., & Havu-Nuutinen, S. (2013). Using technology to open up learning and teaching through improvisation: Case studies with micro-blogs and short message service communications. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 10, 13–22.

Domínguez, A., Saenz-de-Navarrete, J., De-Marcos, L., Fernández-Sanz, L., Pagés, C., & Martínez-Herráiz, J. J. (2013). Gamifying learning experiences: Practical implications and outcomes. Computers & Education, 63, 380–392.

Dreimane, S. (2019). Gamification for education: Review of current publications. In L. Daniela (Ed.), Didactics of smart pedagogy (pp. 453–464). Springer.

Enders, J. (2004). Higher education, internationalisation, and the nation-state: Recent developments and challenges to governance theory. Higher Education, 47(3), 361–382.

Faiella, F., & Ricciardi, M. (2015). Gamification and learning: A review of issues and research. Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society, 11(3), 14–21.

Figg, C., & Jaipal-Jamani, K. (2018). Developing teacher knowledge about gamification as an instructional strategy. In M. Khosrow-Pour (Ed.) Teacher training and professional development: Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications. (pp. 1215–1243). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-5631-2.

Gorbanev, I., Agudelo-Londoño, S., González, R. A., Cortes, A., Pomares, A., Delgadillo, V., ... & Muñoz, Ó. (2018). A systematic review of serious games in medical education: quality of evidence and pedagogical strategy. Medical Education Online, 23(1), 1438718.

Guenaga, M., Arranz, S., Florido, I. R., Aguilar, E., Guinea, A. O., Rayón, A., ... Menchaca, I. (2013). Serious games for the development of employment oriented competences. IEEE Journal of Latin-American Learning Technologies, 8(4), 176–183

Gupta, P., & Goyal, P. (2022). Is game-based pedagogy just a fad? A self-determination theory approach to gamification in higher education. International Journal of Educational Management., 36(3), 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-04-2021-0126

Hassan, M. A., Habiba, U., Majeed, F., & Shoaib, M. (2019). Adaptive gamification in e-learning based on students’ learning styles. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1588745

Howard, N. J. (2022). Lecturer professional identities in gamification: A socio-material perspective. Learning, Media and Technology, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2022.2086569

Huang, R., Spector, J. M., & Yang, J. (2019). Educational technology a primer for the 21st century. Springer.

Hung, C. Y., Sun, J. C., & Liu, J. Y. (2019). Effects of flipped classrooms integrated with MOOCs and game-based learning on the learning motivation and outcomes of students from different backgrounds. Interactive Learning Environments, 27(8), 1028–1046.

Junior, E., Reis, A. C. B., Mariano, A. M., Barros, L. B., de Almeida Moysés, D., & da Silva, C. M. A. (2019). Systematic literature review of gamification and game-based learning in the context of problem and project based learning approaches. In 11th International Symposium on Project Approaches in Engineering Education (PAEE) 16th Active Learning in Engineering Education Workshop (ALE). Hammamet, Tunisia.

Kasurinen, J., & Knutas, A. (2018). Publication trends in gamification: A systematic mapping study. Computer Science Review, 27, 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosrev.2017.10.003

Kim, S., Song, K., Lockee, B., & Burton, J. (2018). What is gamification in learning and education? In S. Kim, K. Song, B. Lockee, & J. Burke (Eds.), Gamification in learning and education (pp. 25–38). Springer.

King-Sears, M., & Evmenova, A. (2007). Premises, principles, and processes for integrating technology into instruction. Teaching Exceptional Children, 40(1), 6–14.

Klemke, R., Eradze, M., & Antonaci, A. (2018). The flipped MOOC: Using gamification and learning analytics in MOOC design—a conceptual approach. Education Sciences, 8(1), 1–13.

Lai, J. W., & Bower, M. (2020). Evaluation of technology use in education: Findings from a critical analysis of systematic literature reviews. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 36(3), 241–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12412

Majuri, J., Koivisto, J., & Hamari, J. (2018). Gamification of education and learning: A review of empirical literature. In Proceedings of the 2nd International GamiFIN Conference, GamiFIN 2018. CEUR-WS.

Marsh, H. W. (2007). Students’ evaluations of university teaching: Dimensionality, reliability, validity, potential bias and usefulness. In R. P. Perry & J. C. Smart (Eds.), Scholarship of teaching and learning in higher education: An evidence-based perspective (pp. 319–383). Springer.

Martí-Parreño, J., Seguí-Mas, D., & Seguí-Mas, E. (2016). Teachers’ attitude towards and actual use of gamification. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 228, 682–688.

Meier, E. B. (2021). Designing and using digital platforms for 21st century learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(1), 217–220.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for integrating technology in teachers’ knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054.

Molenaar, I., & van Schaik, A. (2017). A methodology to investigate classroom usage of educational technologies on tablets. In S. Aufenanger & J. Bastian (Eds.), Tablets in Schule und Unterricht. Forschungsergebnisse zum Einsatz digitaler Medien (pp. 87–1116). Springer.

Moore-Russo, D., Wiss, A., & Grabowski, J. (2018). Integration of gamification into course design: A noble endeavor with potential pitfalls. College Teaching, 66(1), 3–5.

Muntean, C. I. (2011). Raising engagement in e-learning through gamification. In Proc. 6th international conference on virtual learning ICVL (Vol. 1, pp. 323–329).

Murillo-Zamorano, L. R., López Sánchez, J. Á., Godoy-Caballero, A. L., & Bueno Muñoz, C. (2021). Gamification and active learning in higher education: Is it possible to match digital society, academia and students’ interests? International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(1), 1–27.

Nacke, L., & Deterding, S. (2017). The maturing of gamification research. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 450–454.

Namoco, S. (2021). Determinants in the use of Web 2.0 tools in teaching among the Philippine public university educators: A PLS-SEM analysis of UTAUT. Asia Pacific Journal of Educators and Education, 36(2), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.21315/apjee2021.36.2.5

Nasution, A. K. P. (2021). Education technology research trends in Indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pacific Journal of Educators and Education, 36(2), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.21315/apjee2021.36.2.4

Nousiainen, T., Kangas, M., Rikala, J., & Vesisenaho, M. (2018). Teacher competencies in gamebased pedagogy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 74, 85–97.

Oliveira, W., Hamari, J., Shi, L., Toda, A., Rodrigues, L., Palomino, P., & Isotani, S. (2022). Tailored gamification in education: A literature review and future agenda. Education and Information Technologies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11122-4

Perryer, C., Celestine, N. A., Scott-Ladd, B., & Leighton, C. (2016). Enhancing workplace motivation through gamification: Transferrable lessons from pedagogy. The International Journal of Management Education, 14(3), 327–335.

Reeve, J., & Tseng, C. M. (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(4), 257–267.

Sánchez-Mena, A., & Martí-Parreño, J. (2017). Drivers and barriers to adopting gamification: Teachers’ perspectives. Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 15(5), 434–443.

Santos-Villalba, M., Leiva Olivencia, J., Navas-Parejo, M., & Benítez-Márquez, M. (2020). Higher education students’ assessments towards gamification and sustainability: A case study. Sustainability, 12(20), 8513. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208513

Seaborn, K., & Fels, D. I. (2015). Gamification in theory and action: A survey. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 74, 14–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2014.09.006

Shahid, M., Wajid, A., Haq, K. U., Saleem, I., & Shujja, A. H. (2019). A review of gamification for learning programming fundamental. In 2019 International Conference on Innovative Computing (ICIC) (pp. 1–8). IEEE.

Shroff, R., Keyes, C., & Wee, L. H. (2020). Gamified pedagogy: Examining how a phonetics app coupled with effective pedagogy can support learning. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 17(1), 104–116.

Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–22.

Simmons, N., & Taylor, K. (2019). Leadership for the scholarship of teaching and learning: Understanding bridges and gaps in practice. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 10(1), 1–18.

Strmečki, D., Bernik, A., & Radošević, D. (2015). Gamification in e-learning: Introducing gamified design elements into e-learning systems. Journal of Computer Science, 11(12), 1108–1117.

Subhash, S., & Cudney, A. (2018). Gamified learning in higher education: A systematic review of the literature. Computers in Human Behavior, 87, 192–206.

Swacha, J. (2021). State of research on gamification in education: A bibliometric survey. Education Sciences, 11(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11020069

Tan, L., Balakrishnan, N., & Varma, N. (2022). Teaching ST concepts during a pandemic: Modes for engaging learners. Asia Pacific Journal of Educators and Education, 37(1), 157–179. https://doi.org/10.21315/apjee2022.37.1.8

Torrisi-Steele, G., & Drew, S. (2013). The literature landscape of blended learning in higher education: The need for better understanding of academic blended practice. International Journal for Academic Development, 18(4), 371–383.

Vikas, S., & Mathur, A. (2022). An empirical study of student perception towards pedagogy, teaching style and effectiveness of online classes. Education and Information Technologies, 27(1), 589–610. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10793-9

Wang, A. Y. (2022). Understanding levels of technology integration: A TPACK scale for EFL teachers to promote 21st-century learning. Education and Information Technologies, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11033-4

Wismath, S. L. (2013). Shifting the teacher-learner paradigm: Teaching for the 21st century. College Teaching, 61(3), 88–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2012.752338

Zainuddin, Z. (2018). Students’ learning performance and perceived motivation in gamified flipped-class instruction. Computers & Education, 126, 75–88.

Zainuddin, Z., Chu, S. K. W., Shujahat, M., & Perera, C. J. (2020). The impact of gamification on learning and instruction: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Educational Research Review, 30, 100326.

Zhang, Y., & O’Halloran, K. L. (2013). Toward a global knowledge enterprise: University websites as portals to the ongoing marketization of higher education. Critical Discourse Studies, 10(4), 468–485.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Short Term Grant from Universiti Sains Malaysia (304/PJJAUH/6315231)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kabilan, M.K., Annamalai, N. & Chuah, KM. Practices, purposes and challenges in integrating gamification using technology: A mixed-methods study on university academics. Educ Inf Technol 28, 14249–14281 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11723-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11723-7