Abstract

Collaborative activities are a method used in higher education to develop the higher-order skills that students need to succeed in today’s workforce. However, instructors have continued to make the integration of online collaborative activities a low priority. The purpose of this study was to explore the influence of personal attitude on instructor intent to integrate collaborative activities. The principal results determined that participant behavioral beliefs determining personal attitude had a negative influence on instructor intent. The primary areas of influence were lack of real value, the increased difficulty with managing the activity, instructor challenges, and online student expectations. Major conclusions include providing instructors with expertise in instructional design and the tools needed to assess group performance, integrating a method for peer assessment, and implementing student contracts may have a positive impact on personal attitude. Future research should explore whether these strategies alter the intent to integrate online collaborative activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Workforce preparation requires students to come prepared with the ability to communicate, problem-solve, and work as part of a team (National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2019). However, a majority of managers believe college graduates need to be better prepared in these essential skills (National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2019). The ability to work as part of a team is critical in high-risk, high workload fields such as healthcare (Dinh et al., 2021; Flin & O’Connor, 2017; Hekmat et al., 2015; Kossaify et al., 2017; Poulin & Straut, 2016).

Collaborative activities are a method used in higher education for workforce preparation because they require students to think critically, communicate, and work as part of a team (Collins, 2014; Ellis & Hafner, 2008; Vlachopoulos et al., 2020). However, existing studies have documented that most undergraduate instructors do not integrate collaborative activities in online undergraduate courses as a regular educational practice (Al-Hunaiyyan et al., 2020; Eagan et al., 2014; Kilgour & Northcote, 2018; McNeill et al., 2012; Pandya et al., 2021; Rienties et al., 2013; Santos et al., 2019). The topic of this study was the influence of personal attitude on instructor intent to integrate collaborative activities in online undergraduate courses preparing students for a career in healthcare. The following is a literature review on the need to transfer higher-order skills to the workforce, collaborative activities in higher education, the slow integration of online collaborative activities, and designing collaborative activities for online learning.

2 Literature review

2.1 The need to transfer skills to the workforce

The National Association of Colleges and Employers Job Outlook 2020 survey determined that over 86% of employers seek candidates with a college degree who can provide evidence of their ability to think critically, problem-solve and work as part of a team (National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2019). These competencies are easier to develop before entering the workforce when students are still in college, focused on learning, and more open to developing new skills (American Management Association, 2012). However, most employers believe there is a gap between the skills they deem essential in the workforce and the proficiency of college graduates to demonstrate these skills. For example, although 99.0% of employers consider problem-solving and critical thinking essential skills, they also believe only 60.4% of college graduates are highly proficient in these same competencies (National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2019).

The development of higher-order skills is especially important in work environments such as healthcare that are considered high-risk because poor skills in critical thinking, communication, and teamwork cause 65% to 80% of preventable errors (Dinh et al., 2021; Flin & O’Connor, 2017; Hekmat et al., 2015; Kossaify et al., 2017). An effective strategy for reducing preventable errors is to train students with higher-order skills (Hughes et al., 2016; Weaver et al., 2014). Salas et al. (2018) identified two studies that examined the effectiveness of team training to reduce preventable errors and improve the safety of patient care. The first was a literature review of 26 studies conducted between 2000 and 2012 (Weaver et al., 2014). Ten of the studies reviewed documented team training resulted in statistically significant improvements in clinical processes and patient safety. The second was a meta-analysis of 129 studies identified in 10 different databases from the start date of the database through April 2015 (Hughes et al., 2016). According to Salas et al. (2018), the findings from the meta-analysis performed by Hughes et al. demonstrated a 29% improvement in learning, a 23% increase in skill transfer, an 18% reduction in medical errors, and a 14% improvement in patient outcomes because of team training. This research contextualizes the need to transfer higher-order skills to the field of healthcare.

2.2 Collaborative activities in higher education

Collaborative activities are an instructional practice used in higher education to promote deeper learning and develop higher-order skills (Collins, 2014; Ellis & Hafner, 2008; Vlachopoulos et al., 2020). The National Research Council (2012) described deeper learning as “the ability to transfer new knowledge to another situation” (p. 5). Higher-order skills include teamwork and collaboration skills such as leadership, conflict management, negotiation, and communication (National Research Council, 2012). According to Johnson et al. (2007), collaborative activities should expect students to demonstrate “positive interdependence, individual accountability, meaningful interaction, appropriate use of social skills, and group processing” (p. 23). Several studies have explored the effectiveness of collaborative learning in higher education.

Johnson et al. (2007) analyzed the results of 168 studies conducted between 1924 and 1997 to assess the impact of collaborative activities on the achievement of learning outcomes in higher education. The results determined that students who achieve overall scores in the 53rd percentile working on an individual basis would score in the 70th percentile working collaboratively as part of a group (Johnson et al., 2007). A second meta-analysis of 39 studies conducted from 1980 through 1999 also confirmed that small-group learning with undergraduate students had significant positive effects on academic achievement (Springer et al., 1999).

Kilgo et al. (2015) analyzed the impact of different instructional practices on the achievement of learning outcomes in undergraduate students. The results demonstrated that collaborative learning and participation in undergraduate research were the only two instructional practices to significantly affect the achievement of learning outcomes (Kilgo et al., 2015). Another study conducted by Marbach-Ad et al. (2016) examined the impact of small group activities (i.e., three to four students) compared to traditional lecture format on the achievement of learning outcomes in an undergraduate course. Statistical analysis of the examination scores resulted in a significantly higher level of achievement for students enrolled in the small group activity format after controlling for major, gender, underrepresented minority status, and cumulative grade point average (Marbach-Ad et al., 2016).

2.3 Slow integration of online collaborative activities

Several studies have explored the integration of collaborative activities in online higher education. McNeill et al. (2012) compared the intended use of virtual conferencing software for online collaboration in higher education with the actual use of the technology. Results demonstrated that 90% of participants targeted intended learning outcomes for online collaborative activities at the Bloom revised taxonomy mid-level of applying (McNeill et al., 2012). However, survey responses regarding the actual use of technology demonstrated a low utilization (< 10%) of virtual conferencing software for assessment of mid to higher-order learning outcomes (McNeill et al., 2012). Most participants (73%) used virtual conferencing software for discussion forums that primarily assessed lower-level outcomes such as recall and understanding (McNeill et al., 2012).

Rienties et al. (2013) examined instructor perceptions regarding the design and integration of technology-enhanced teaching strategies such as online collaborative activities. One of the items on the survey instrument assessed how often instructors used information communication technology (ICT) to facilitate online collaborative activities. Analysis of the data revealed that 54% of instructors did not use ICT as a regular online teaching strategy (Rienties et al., 2013). A report published by Eagan et al. (2014) summarized the results of a survey of undergraduate instructors in higher education. The results determined that nearly all the respondents (99%) ranked developing critical thinking skills as a “very important” or “essential” learning outcome (Eagan et al., 2014, p. 5). However, fewer than half of undergraduate instructors (45%) incorporated collaborative activities as a regular teaching practice in online courses (Eagan et al., 2014).

More recently, a study by Kilgour and Northcote (2018) explored instructor perceptions of the ideal learning environment in online higher education. The results demonstrated that instructors rank the use of collaborative activities for student interaction as very low on their list of preferences for the ideal online learning environment (Kilgour & Northcote, 2018). A literature review of 10 articles by Santos et al. (2019) confirmed there is a conflict between instructor beliefs regarding collaborative learning and the actual use of this teaching strategy in higher education. A study by Al-Hunaiyyan et al. (2020) explored the use of tools embedded within the learning management system in a sample of 58 higher education instructors. The results determined a high utilization of administrative tools (i.e., announcements, files, assignments) to deliver content, and a low utilization of interactive tools that promote collaboration. A study by Pandya et al. (2021) explored the transition to online higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic in a sample of 116 instructors across 22 countries. Although the transition to online learning resulted in no significant differences in lesson content and the level of technical support, there was a significant decline in the application of teaching methods such as collaborative learning.

These studies demonstrate that even though collaborative activities positively impact the development of higher-order skills and there is a need to transfer those skills to the workforce, online collaborative activities are a low priority for instructors in higher education. Designing activities to achieve outcomes in the online environment requires a significant level of preplanning and a good understanding of instructional design principles (Rovai, 2004).

2.4 Designing collaborative activities for online learning

Designing online collaborative activities is more challenging for instructors than is designing similar activities for the face-to-face classroom (Albrahim, 2020; Kebritchi et al., 2017; Kurucay & Inan, 2017). There are several reasons for the increased level of difficulty. First, the instructor’s role in the online classroom has been defined as “content facilitator, metacognition facilitator, process facilitator, advisor/counselor, assessor, technologist, and resource provider” (Denis et al., 2004, p. 4). These multiple roles increase the complexity of teaching an online course. Second, the integration of collaborative activities in the online classroom requires virtual conferencing software because of the geographic distance among students (Robinson et al., 2017; Wingo et al., 2017). The ongoing development of new tools for online collaboration makes adapting to the use of virtual conferencing software a challenge for instructors (Chang & Hannafin, 2015). Third, the intentional design of collaborative activities for online learning requires instructors to know instructional design principles (van Rooij & Zirkle, 2016). According to Borokhovski et al. (2016), collaborative activities intentionally designed for online learning had a more significant effect on the achievement of learning outcomes. The four major areas of focus regarding the intentional design of online collaborative activities include the types of activities that engage online students, optimal strategies for group formation, the impact of instructor presence, and methods for virtual communication (Robinson et al., 2017).

According to Chapman and Van Auken (2001), there is a significant correlation between students’ attitudes toward collaborative activities and the strategies used by instructors to engage students. Two strategies recommended by Chang and Brickman (2018) to engage online students are the use of peer assessment and the use of student contracts. Peer assessment tools provide students a formal mechanism to assess individual group member performance and inform the instructor of problems with member accountability, such as social loafing or free-riding (Chang & Brickman, 2018). Student contracts provide the group with a tool to agree on expectations regarding participation and performance before the project begins (Chang & Brickman, 2018).

Design strategies related to group formation include group size, assigning groups, and member roles (Cherney et al., 2018). According to Shaw (2013), students organized in small groups of two to six students participate at a significantly higher level and experience significantly higher scores on exams than large groups. A qualitative study performed by Scager et al. (2016) also determined that collaborative activities are more effective when groups are limited to between three and four members. Groups can be assigned using random, learner-driven, and instructor-driven methods (Cherney et al., 2018; Sadeghi & Kardan, 2015). A case study conducted by Sadeghi and Kardan (2015) determined that students had a higher level of performance and expressed a higher level of satisfaction with collaborative activities when they chose the group members (i.e., learner-driven), rather than in random or instructor-driven methods (Sadeghi & Kardan, 2015). According to Vercellone-Smith et al. (2012), however, this approach can be difficult to implement in online courses, and there is still a debate regarding the most effective strategy for assigning groups in online collaborative activities. Assigning group member roles before initiating the collaborative activity provides structure to the group and also improves group member accountability (Wise et al., 2012). Assigned roles might include leader, researcher, writer, editor, facilitator, supporter, or presenter (Wade et al., 2016).

Oyarzun et al. (2018) determined a significantly positive relationship between a high instructor rating for student knowledge transfer and a high student rating for instructor presence (Oyarzun et al., 2018). Also, the only strategy common among the instructors with the highest rating for instructor presence was the integration of online collaborative activities with milestone assignments (Oyarzun et al., 2018). Milestone assignments improve the quality of collaborative activities by providing students with active instructor monitoring, intervention when needed, and formative feedback (Brindley et al., 2009; Smith, 2018).

Lastly, online collaborative activities require instructors to design a method for virtual communication (Robinson et al., 2017). Asynchronous forms of virtual communication provide flexibility because they do not require real-time participation (LaBeouf et al., 2016; Rezaei, 2017). Examples of asynchronous communication tools include wikis, blogs, email, social media, and threaded discussion forums (Lim, 2017). Synchronous forms of virtual communication occur in real-time (Lim, 2017). Examples of synchronous communication tools include virtual chat rooms, video conferencing software, interactive whiteboards, and instant messaging (Lim, 2017). Although asynchronous communication provides flexibility for students, a study conducted by Khalil and Ebner (2017) determined that the development of higher-order skills was significantly better when the group used a video tool for synchronous communication (Khalil & Ebner, 2017).

2.5 Need for research

According to Zawacki-Richter et al. (2009), research conducted between 2000 and 2008 on the topic of online collaboration was dominated by issues associated with web-based communication technology and instructional design principles. Several studies since 2009 have continued to explore instructor intent to use web-based communication technology in online courses (Sadaf et al., 2012, 2016; Teo & Lee, 2010). Recent studies have also provided important information regarding the intentional design of online collaborative activities (Chang & Brickman, 2018; Cherney et al., 2018; Oyarzun et al., 2018). This existing body of research begins to address the slow integration of online collaborative activities by providing valuable insights into the issues associated with developing these technical competencies.

According to the theory of planned behavior, however, there may be factors other than technical competence influencing behavioral intent (Ajzen, 1991). There is limited research exploring all of the factors that may be influencing instructor intent to integrate online collaborative activities in higher education (De Hei et al., 2015; Donche & Van Petegem, 2011; Ünal, 2020). One of these factors is personal attitude (Ajzen, 1991). This study sought to investigate the influence of personal attitude on instructor intent to integrate collaborative activities in online undergraduate courses. The research question was: What is the influence of personal attitude on instructor intent to integrate collaborative activities in online undergraduate courses preparing students in the field of healthcare at select universities in the state of Florida?

3 Method

3.1 Research sites and participants

This qualitative study was conducted using a multiple case approach. A multiple case approach yields different perspectives through the replication of the same procedures for data collection with more than one site (Yin, 2017). The case study approach typically includes a relatively small sample of participants purposefully selected because of their understanding of the central phenomenon (Rahman, 2016). The state of Florida was chosen for site selection based on the breadth of online undergraduate course delivery as the State University System of Florida ranked second in the nation in terms of online student enrollment (State University System of Florida, 2019). The two universities identified for case selection had a percentage of online undergraduate students above the system-wide percentage of 72%, and both universities offered online courses in healthcare (State University System of Florida, 2019). The targeted population of instructors at the two universities chosen for site selection needed to have at least one year of online teaching experience and responsibility for developing course activities. The targeted population was further narrowed to instructors not integrating online collaborative activities to explore the motivational factors limiting this educational practice. Participants from the targeted population were purposefully recruited based on these criteria using an electronic screening survey.

Approval to proceed was obtained from the university institutional review board before the initiation of the study to protect the rights of the study participants. The application to the institutional review board included letters of authorization from both sites. The final sample of 10 participants included four participants from Site 1 and six participants from Site 2. According to Stake (2006), a sample size of four to 10 cases from each site in multiple case studies is needed for common themes to emerge from the qualitative data. The sample of participants included instructors in higher education with a wide range of both teaching experience and online course enrollment. All four participants at Site 1 taught online courses in the health management program. Two of the six participants at Site 2 taught online nursing courses, and four of the six at Site 2 participants taught online courses in the public health program. Seven participants (70%) were male, and three (30%) were female. The average online course enrollment for all participants was 109 students, with a range of 35 to 400 students. The average online teaching experience for all participants was 7.2 years, with a range of 1.5 to ten years.

3.2 Instruments and procedure

One-on-one interviews and a focus group interview were used to collect the data. All interviews were conducted virtually. Virtual conferencing software ensured the capability for two-way audio and video teleconferencing, as well as a digital recording. A semi-structured one-on-one interview protocol incorporated open-ended questions that explored instructors’ attitudes through the elicitation of beliefs regarding the usefulness and the difficulty associated with integrating online collaborative activities (Ajzen, 1991; Sadaf et al., 2012). Probing and follow-up questions provided a method for collecting more complex responses that would add breadth and depth to the qualitative data (Ritchie et al., 2013). The purpose of the focus group interview was to corroborate and expand on the major themes that emerged during the one-on-one interviews with a group perspective (Berg & Lune, 2012). Field testing provided a method to test and revise both the one-on-one interview protocol and focus group interview protocol for construct validity (Yin, 2017).

The one-on-one interviews (N=10) occurred after receiving each participant’s signed informed consent statement and recorded media addendum electronically through a secure web-based document management service. Data saturation was reached upon completion of the one-on-one interviews. At this point, all participants received an invitation to participate in the focus group. Participation was voluntary, and five of the 10 participants agreed to join the focus group interview. According to Krueger (2014), focus groups should include five to eight participants to be small enough to encourage dialogue among members and large enough to generate diverse insights. The leading questions developed for the focus group interview explored participants’ beliefs regarding the difficulties associated with managing online collaborative activities, the definition of a meaningful experience for students, and the steps instructors can take to improve the experience for students.

The elicitation of salient beliefs regarding “perceived usefulness” and “perceived ease of use” determine an instructors’ attitude toward the use of technology to foster online collaboration (Sadaf et al., 2012, p. 48). The definition of perceived usefulness is the perceived value for enhancing student learning and improving student engagement (Sadaf et al., 2012). The following leading interview question elicited behavioral beliefs regarding perceived usefulness: “Do you believe online collaborative activities are useful and achieve valued outcomes? Why or why not?” The definition of perceived ease of use is the perceived level of difficulty associated with integrating collaborative activities in online courses (Sadaf et al., 2016). The following leading interview question elicited behavioral beliefs regarding perceived ease of use: “Can you describe for me your beliefs regarding how easy or difficult an online collaborative activity is for instructors to set-up and manage?”

3.3 Data analysis

The interview data were transcribed into electronic files and analyzed using qualitative content analysis (Creswell & Poth, 2017). The coding process involved describing an associated text segment with notes placed in the margins of the electronic files. The organization of notes into categories of information generated an initial list of approximately 25 codes. Codes were then combined into higher-level categories to generate a list of three to six descriptive headings. Themes were interconnected and organized into layers wherever possible to include additional insights and identify inconsistent or discrepant data (Creswell & Poth, 2017).

A peer-review process known as an intercoder agreement was used to ensure the findings are credible (Silverman, 2013). Two professional peers experienced in qualitative research methods but who were not involved in the study were recruited to participate in this process. The review included a subsample of three cases (25%) representative of the study sample. Discussion continued until reaching an agreement of over 85% through consistency on the assignment of codes to text segments, the aggregation of codes into higher-order categories, and the identification of common themes.

4 Results

4.1 Perceived usefulness

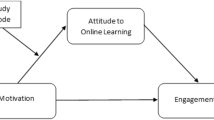

A predominant number of participants answered the interview question on perceived usefulness by including beliefs regarding both intended value and real value in the online classroom. For the purposes of this study, the definition of intended value is the outcomes instructors expect to achieve, and the definition of real value is the actual outcomes achieved from the integration of online collaborative activities. Intended value was coded in responses regarding perceived usefulness when participants used terms such as “ideally”, “should”, “capable of”, “can”, or “may be able” to describe their beliefs regarding the achievement of outcomes. Real value was coded in responses when participants used terms such as “in reality” or “actually” when describing their beliefs regarding perceived usefulness. Real value was also coded in responses when participants expressed a belief regarding actual outcomes that contradicted or further clarified their belief regarding intended outcomes. Probing questions revealed several strategies the participants believed should be used to enhance the value of online collaborative activities. As a result, the three themes that emerged from an analysis of the data related to perceived usefulness were intended value, real value, and enhancing value (Fig. 1).

All 10 participants (100%) believed there is an intended value from the use of online collaborative activities. Six participants (60%) believed that collaborative activities are used in the classroom to achieve higher-order learning outcomes. For example, one instructor reported, “Yes, online collaborative activities are very capable of achieving higher-order outcomes.” A second instructor believed that online collaborative activities “can facilitate the development of problem-solving and critical thinking” skills, which “sets students up for success in the workforce.”

Six participants (60%) believed that online collaborative activities should mimic the real world challenges of healthcare teams and virtual collaboration. Most instructors were very focused on workforce preparation during the one-on-one interview. One instructor used a specific example to make her point:

The online class gives us an additional ability [because] students are not always connected, which is what we see in healthcare. We are giving them an opportunity to utilize technologies and to experience that group dynamic like they would using web conferencing software in the workforce. [Online collaborative activities] help to mimic situations in the real world and gives [students] an opportunity to touch the technology before they are in a real job.

A second instructor similarly stated, “I think [online collaborative activities] prepare [students] for the increased use of technology in the workforce before they graduate.”

Five instructors (50%) believed that online collaborative activities could reduce the grading burden for instructors. For example, one instructor stated:

I would only have to grade 20 projects instead of 80 projects. So there is some self-preservation. Right before or after midterms, you are grading a quarter of the projects because you had [students] do a group project instead of an individual project.

Three participants (30%) believed that the intended value of online collaborative activities would depend on the course objectives. The focus group interview provided supplemental information to reinforce the theme of intended value. The group perspective from the focus group interview was that online collaborative assignments should reflect real world practice by requiring virtual meetings and a formal presentation. However, most participants qualified their responses regarding intended value with beliefs regarding the real value of collaborative activities in the online classroom.

Most of the instructors (70%) who believed online collaborative activities have an intended value also believed they lack real value in the online classroom. One instructor reported, “There are obviously some elements of divide and conquer for doing background work. But ultimately, what you want [students] to do is discuss their findings with each other. That is what true collaboration is all about, in my opinion.” Another instructor believed “the [real] value comes down to can they work on a team” and whether or not the students “know how to handle conflict resolution when it occurs.” He believed achieving real value is “all about group dynamics, which requires synchronous collaboration.” However, most online students “want to do [online assignments] on their own time because they are scattered geographically.” A third instructor stated, “The reason students are in online learning is not to do things synchronously.” He was, therefore, “not sure” there is real value to online collaborative activities. In addition to the themes of intended value and real value, most participants included recommendations to enhance the value of online collaborative activities in the discussion regarding perceived usefulness.

Enhancing value was coded in responses on the topic of perceived usefulness when participants made recommendations for educational practice to enhance the value of online collaborative activities. Nine participants (90%) believed that intentional project design enhances the perceived usefulness of online collaborative activities. One instructor summarized this belief by stating, “Instructors should make sure the class is built to encourage and provide some sort of support for actually reaching the [intended] outcomes. Then, there is really no excuse for the students not to participate.” Participants recommended two strategies for the intentional design of collaborative online activities already discussed under the theme of real value: designing projects that require a collaborative rather than a divide-and-conquer approach and requiring human interaction through synchronous collaboration. Other recommendations included clarifying group member responsibilities, showcasing student work, and using a grading system that encourages student creativity. Three participants (30%) recommended using random group assignments to enhance the perceived usefulness of online collaborative activities. For example, on instructor believed that random group assignments should be used in online courses because random groups “can be generated fairly and automatically by the learning management system.” A second instructor recommended using random group assignments because it is “much harder” for instructors to assign groups in the online environment. He believed it is harder for instructors to assign groups because “we do not know [the students] as well” as in a face-to-face course. Lastly, one participant believed that online collaborative activities become more effective as instructors gain experience through trial and error.

4.2 Perceived ease of use

All participants answered the interview question on perceived ease of use by clarifying beliefs for both the set-up and management of collaborative activities in the online classroom. Set-up versus management was coded in responses when participants included the terms “set-up” or “manage” to describe their perceptions regarding the level of difficulty associated with integrating online collaborative activities. In response to probing questions, participants provided additional information regarding the challenges experienced by instructors and the unique expectations of online students. Instructor challenges were coded in responses on the topic of perceived ease of use when participants identified issues associated with planning, coordinating, or implementing the collaborative activity. Online student expectations were coded in responses on the topic of perceived ease of use when participants described student assumptions regarding the online learning environment. Online student expectations were also coded in responses when participants recommended strategies to improve the impact of those student assumptions on the instructor’s perceived level of difficulty. The three themes that emerged from data analysis related to perceived ease of use were set-up versus management, instructor challenges, and online student expectations (Fig. 2).

All 10 participants (100%) believed that collaborative activities are simple for instructors to set-up in online courses. For example, one instructor reported, “I think setting up an assignment, with the right pre-work, is pretty easy. I am pretty deliberate in how I set-up my assignments.” Another instructor similarly stated, “If [an online collaborative assignment] is preplanned well, it’s not a difficult experience in terms of just setting up the assignment. But [setting it up] takes a lot of forethought, a lot of preplanning, and a lot of research.” However, most of the participants (80%) also believed that collaborative activities in online courses are difficult for instructors to manage. One instructor made the following comments regarding the management of group dynamics:

I believe it is very difficult to manage online groups. You have to manage multiple people you can’t see on a regular basis to judge how they’re doing and how they’re participating. Typically, we only find out that things are going wrong after the fact.

A second instructor similarly stated:

Managing these activities is difficult. I have students all over the world. Right now, I have a student in Spain, a student in Japan, a student in Hawaii, so the time zones make it nearly impossible for them to do group work.

However, two instructors had contradictory beliefs regarding the management of online collaborative activities. One instructor reported, “Online collaborative activities are not difficult to manage because all faculty are properly trained.” A second instructor also stated, “Online students are adult learners, so there should be no need to manage the activity if it is set-up efficiently. Students need to learn to manage a team on their own.” These contradictory beliefs identify exceptions to the previous data regarding the theme of set-up versus management.

Participants identified three major logistical issues related to the theme of instructor challenges (Fig. 2). In order of importance based on the number of participant responses, the issues are instructor workload, managing student complaints, and assessment of group performance. Six participants (60%) identified instructor workload as a challenge because of large class sizes and heavy course loads. For example, one instructor reported the following:

If you don’t keep the group size a manageable number, [a collaborative activity] is hard to do. For a group presentation, you probably don’t want more than five [students]. In a class of 150 [students], that’s 30 groups you’re going to have to manage.

Another instructor believed that instructors put “so much time into grading assignments that to add something like this could be overwhelming.” However, two instructors had contradictory beliefs regarding the impact of class size on instructor workload. For example, one instructor responded, “I’m not sure that [collaborative activities] would be more difficult online since you’re removing the time component and limitations of [a face-to-face] classroom. So, I’m not sure that the number of students would make a huge difference.” Five participants (50%) identified student complaints as excessive and time-consuming for instructors to manage. One instructor believed that most students are “not well equipped” to handle these situations, “or they wait to talk with the instructor about problems until they submit the assignment.” Regarding the challenges associated with managing synchronous presentations, a second instructor shared the following belief:

I believe that setting up synchronous online collaborative activities is more difficult than setting up asynchronous activities. I think synchronous activities are more valuable than asynchronous activities. But in the online format, because students are [participating] at different times, they have different life requirements. [A synchronous component] adds to the level of difficulty.

A third instructor also reported, “I feel that [synchronous collaboration] is typically not set-up in the online courses I am working with because of the challenge of organizing students to come together and make sure that they are doing equal amounts of work.” Two participants (20%) believed that the assessment of group performance creates an additional challenge for instructors. One instructor summarized this challenge by stating, “It seems like you [spend] more effort on assessment than on actual learning if that makes sense.” He responded, “Grading is very difficult. How am I to discriminate who did what in terms of contribution? I find that to be true in the in-class sessions as well, but the online collaborative experience is very different in that context.” Another instructor reported, “The types of group work that we’re asking them to do are typically higher-order level assignments. Having to manage that in terms of a grading process would be difficult.”

Participants identified three areas of significance related to the theme of online student expectations (Fig. 2). The first was that online students expect an independent, convenient, and consistent learning environment. The second was that instructors should realign online student expectations to meet the objectives of collaborative activities by incorporating peer assessment and student participation contracts. The third area of significance was that instructors should clarify the expectations of online collaborative activities with grading rubrics and milestone assignments.

Seven participants (70%) believed that online students expect an independent, convenient, and consistent learning environment. For example, one instructor responded, “Students don’t want to be engaged when they are in an online environment.” He believed that students would say, “I can do [assignments] when I want to, I can do [assignments] at one [o’clock] in the morning. I don’t have to be present with others.” A second instructor suggested that some online students are “just in transaction mode, and it’s not going to matter what you do because they’re just doing the transactions.”

Six participants (60%) recommended incorporating peer assessment tools or student contracts as strategies to realign online student expectations with the objectives of collaborative activities. One instructor reported, “Students are required to give feedback to their group members. They grade each other at the end of [the collaborative activity], which impacts their grade, so they know if they did not pull their weight.” This same instructor also recommends having the students “create a project charter, which is a contract with each other to set specific dates that they want to meet and times they are available.” Six participants (60%) recommended using either grading rubrics or milestone assignments to clarify the expectations of the collaborative activity. One instructor uses a similar approach for independent online projects: “I tend to break things into pieces. Then, at the end, we put the pieces together. Personally, the less confused [students] are, the easier the assignment is for me to manage.”

4.3 Influence on instructor intent

The two themes that emerged regarding perceived usefulness that influenced instructor intent were intended value and real value. All 10 participants believed that there is an intended value for the use of online collaborative activities. Participants believed that instructors expect online collaborative activities to achieve higher-order outcomes, mimic real world challenges, or reduce the grading burden for instructors. However, a key finding regarding perceived usefulness was that most participants (70%) expressed some level of uncertainty regarding the real value of online collaborative activities (Table 1). The perception that online collaborative activities are not useful because they lack real value negatively influenced instructor intent. A theme that emerged regarding perceived ease of use that influenced instructor intent was set-up versus management. All 10 participants believed online collaborative activities are not difficult to set-up. However, a key finding was that a predominant number of participants (80%) perceived online collaborative activities as difficult for instructors to manage (Table 1). Participants specifically described the management of collaborative activities as more difficult to manage online than in the face-to-face classroom due to instructor challenges and student expectations. The perception that online collaborative activities are difficult to manage also had a negative influence on instructor intent.

5 Discussion

5.1 Intended value

All instructors believed that there is an intended value for the use of online collaborative activities. A majority of instructors also believed the intended value is to develop higher-order skills or mimic the real world challenges of virtual collaboration. Training undergraduate students to work collaboratively has a significant effect on the development of higher-order outcomes and is, therefore, an effective strategy for reducing the incidence of preventable errors in healthcare (Gokhale, 1995; Kilgo et al., 2015; Salas et al., 2018). However, to achieve these intended outcomes, instructors also believed that collaborative activities should require the application of new skills and mimic a real world scenario. Research conducted by Robinson et al. (2017) and Stephens and Roberts (2017) supports this finding. There have been similar results in research conducted in the context of healthcare. Studies have documented statistically significant improvements in both clinical processes and patient outcomes as a result of team training that simulates a real world scenario (Weaver et al., 2014). These results have been attributed to the integration of online collaborative activities in healthcare courses because these kinds of activities simulate teamwork across complex health systems, requiring the development of higher-order skills in leadership and conflict management (Mast & Gambescia, 2015).

Several participants believed collaborative activities are integrated into online courses to increase convenience and reduce the grading burden for instructors. One significant advantage to the reduced number of projects that require grading is that it provides instructors with more time to provide constructive feedback (Rezaei, 2017). Lastly, some instructors believed the intended value of online collaborative activities would depend on the course objectives. However, the development of course objectives requires alignment between the purpose of the activity, course design, pedagogical approach, and student learning outcomes (Chang & Hannafin, 2015). Misalignment results in low levels of student engagement, which hinders the achievement of higher-order outcomes (Chang & Hannafin, 2015). Many instructors in higher education lack knowledge in this area and are not well-trained on how to align the use of technology in an online course (Koehler et al., 2013).

5.2 Real value

Although all instructors believed there was an intended value to the use of collaborative activities, 70% of the instructors believed they lack real value in the online classroom. This finding is supported by research documenting instructors who believed that the potential outcome of collaborative activities is the development of higher-order skills did not believe online collaborative activities achieve this same outcome (LaBeouf et al., 2016). According to De Hei et al. (2015), there is a significant correlation between positive instructor beliefs regarding the achievement of learning outcomes in collaborative activities and the use of collaborative activities in the classroom.

Instructors believed real value is achieved through intentional design that leads to meaningful interaction between online students. This belief is supported by Scager et al. (2016), who claimed collaborative activities should require meaningful collaboration among group members. Instructors stated intentional design should require human interaction through synchronous communication. According to Khalil and Ebner (2017), the development of higher-order skills is significantly better when the activity requires meaningful interaction through synchronous communication. Instructors also believed these activities should be intentionally designed to require a collaborative rather than a divide-and-conquer approach. Divide and conquer activities require students to divide the tasks equally among the members rather than engaging in meaningful interaction through collaboration (Lock & Johnson, 2015). Although group members completing an activity with a divide-and-conquer approach will have a deep understanding of their contribution, they will lack participation and a deep understanding of the overall project (Lock & Johnson, 2015).

5.3 Set-up versus management

Instructors specifically described collaborative activities as more difficult to manage online than in the face-to-face classroom. There are several reasons for this phenomenon. First, collaborative activities are considered more difficult when instructors are unable to assess individual student participation and, therefore, unable to objectively assess the development of higher-order skills (Le et al., 2018). Second, this independent, autonomous environment requires the instructor to change their role as a traditional lecturer to the more complex role of a learning facilitator (Cairns & Castelli, 2017; Denis et al., 2004). Third, online instructors and students must adapt to using technology tools to facilitate high-quality interaction. Adapting to technology is a challenge because of the continual development of new tools to support online collaboration (Chang & Hannafin, 2015). Lastly, many instructors in higher education are discipline experts with no formal training in pedagogical strategies, and many instructors in higher education did not experience collaborative or student-centered instruction during the completion of their degree programs (Riebe et al., 2016).

5.4 Instructor challenges

Instructors believed managing student complaints contributes to the increased level of difficulty. Collaborative activities require instructors to spend a significant amount of time managing student complaints regarding schedule conflicts, lack of group member participation, unproductive assignments, or an unfair assessment of the project (LaBeouf et al., 2016; Zygouris-Coe, 2012). According to Zygouris-Coe (2012), instructors typically avoid integrating online collaborative activities because of the time commitment involved in managing student complaints.

Instructors also believed the process of assessing collaborative activities is more difficult in the online environment. The assessment of collaborative activities should include an assessment of both the group project and individual group members’ contributions (Webb, 1994). Assessment of individual group members’ contributions encourages accountability and provides feedback on the member’s ability to communicate, collaborate, solve problems, make decisions, and resolve conflict (Webb, 1994). However, instructors experience more difficulty tracking individual participation in online collaborative activities, which require students to participate using web-based communication tools (An et al., 2008; LaBeouf et al., 2016; Robinson et al., 2017; Wingo et al., 2017).

5.5 Student expectations

Most participants believed that online students expect an independent, convenient, and consistent work environment. However, these expectations do not align with the expectations of a collaborative activity, as described by Johnson et al. (2007). According to LaBeouf et al. (2016), most students perceive collaborative work as not useful in the online environment, and most students enroll in online courses because of the increased flexibility over face-to-face courses. Online students prefer to work independently, primarily because of the challenges of working around work schedules, life priorities, and different time zones (Hampton & El-Mallakh, 2017).

Group member accountability is an important variable influencing students’ attitudes and the efficacy of collaborative activities (Chang & Brickman, 2018). There is a significant correlation between students’ attitudes toward group work and the strategies used by instructors to foster collaboration among members (Chapman & Van Auken, 2001). Two strategies recommended by instructors to foster collaboration among members include peer assessment and student contracts. Peer assessment tools provide students a mechanism to inform the instructor of problems with social loafing or free-riding, and student contracts provide the group a tool to agree on expectations regarding participation and performance (Chang & Brickman, 2018).

Lastly, instructors believed students contribute at a higher level when the activity includes a grading rubric and is broken down into milestone assignments (Brindley et al., 2009). Grading rubrics explain the learning objectives, clarify the expectations for participation, and help group members visualize the assignment (Chowdhury, 2019). Milestone assignments increase opportunities for engagement among the instructor and students and provide more opportunities for the students to receive formative feedback (Smith, 2018).

6 Limitations and further research

The small, purposefully selected sample of instructor participants limits the findings to only the cases sampled (Rahman, 2016). Data collected during the one-on-one interviews came from the participants’ perspective, and the interviewer’s presence may have biased the responses. However, member checking during the focus group interview and negative case analysis ensured that the findings were trustworthy.

Future research could explore whether the implementation of intentional design strategies can change behavioral beliefs regarding the achievement of intended outcomes and alter instructor intent to integrate online collaborative activities. Future research might also examine the impact of reducing instructor workload on the ability to manage online collaborative activities. Lastly, the finding in the current study that group members should be randomly assigned is inconsistent with existing research that suggests students have a higher performance level and express a higher level of satisfaction when they chose their group members (Sadeghi & Kardan, 2015). Future research should continue to explore the most effective strategy for group assignments in online courses.

7 Conclusions

Several conclusions emanate from a critical reflection of the findings in relation to the existing literature. First, instructors understand the intended purpose of collaborative activities but question their usefulness in online courses. Instructors were uncertain whether the intended outcomes are achieved in online courses, especially when they lack intentional design. Providing instructors with expertise in collaborative instructional design strategies may help achieve the intended learning outcomes and change this belief. Second, instructor challenges and online student expectations make collaborative activities more difficult for instructors to manage online than in the face-to-face classroom. Addressing issues related to instructor workload and providing instructors with the expertise and tools needed to assess group performance, integrating a method for peer assessment, and implementing student contracts may change this belief. Third, instructors agree on several issues related to the integration of online collaborative activities. Although this study included male and female participants from two different sites, three different programs, and varying levels of online teaching experience, there was a high level of consistency in participant responses.

The behavior that is the focus of this study is the integration of online collaborative activities in undergraduate healthcare courses. The findings determined that participant behavioral beliefs determining personal attitude had a negative influence on instructor intent. Identification of these negative influences may lead to strategies that change instructor beliefs and improve the utilization of collaborative activities in the online classroom (Madden et al., 1992). The findings also address the current gap in research exploring the low utilization of collaborative activities in the online learning environment.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Al-Hunaiyyan, A., Al-Sharhan, S., & AlHajri, R. (2020). Prospects and challenges of learning management systems in higher education. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 11(12). https://doi.org/10.14569/ijacsa.2020.0111209

Albrahim, F. A. (2020). Online teaching skills and competencies. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 19(1), 9–20. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1239983.pdf.

American Management Association. (2012). Executive summary: AMA 2012 critical skills survey. http://www.amanet.org/uploaded/2012-Critical-Skills-Survey.pdf

An, H., Kim, S., & Kim, B. (2008). Teacher perspectives on online collaborative learning: Factors perceived as facilitating and impeding successful online group work. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 8(1), 65–83. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/24290/.

Berg, B. L., & Lune, H. (2012). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. Pearson.

Borokhovski, E., Bernard, R. M., Tamim, R. M., Schmid, R. F., & Sokolovskaya, A. (2016). Technology-supported student interaction in post-secondary education: A meta-analysis of designed versus contextual treatments. Computers & Education, 96, 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.11.004

Brindley, J., Blaschke, L. M., & Walti, C. (2009). Creating effective collaborative learning groups in an online environment. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 10(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v10i3.675

Cairns, S., & Castelli, P. A. (2017). Team assignments: Planning a collaborative online learning environment. Business Education Innovation Journal, 9(1), 18–24. http://www.beijournal.com/images/2V9N1_final-2.pdf.

Chang, Y., & Brickman, P. (2018). When group work doesn’t work: Insights from students. CBE Life Sciences Education, 17(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-09-0199

Chang, Y., & Hannafin, M. J. (2015). The uses (and misuses) of collaborative distance education technologies. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 16(2), 77–92. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1143842.

Chapman, K. J., & Van Auken, S. (2001). Creating positive group project experiences: An examination of the role of the instructor on students’ perceptions of group projects. Journal of Marketing Education, 23(2), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475301232005

Cherney, M. R., Fetherston, M., & Johnsen, L. J. (2018). Online course student collaboration literature: A review and critique. Small Group Research, 49(1), 98–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496417721627

Chowdhury, F. (2019). Application of rubrics in the classroom: A vital tool for improvement in assessment, feedback and learning. International Education Studies, 12(1), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v12n1p61

Collins, R. (2014). Skills for the 21st century: Teaching higher-order thinking. Curriculum & Leadership Journal, 12. http://www.curriculum.edu.au/leader/teaching_higher_order_thinking,37431.html?issueI

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

De Hei, M. S., Strijbos, J. W., Sjoer, E., & Admiraal, W. (2015). Collaborative learning in higher education: Lecturers’ practices and beliefs. Research Papers in Education, 30(2), 232–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2014.908407

Denis, B., Watland, P., Pirotte, S., & Verday, N. (2004, April 5–7). Roles and competencies of the e-tutor [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the Networked Learning Conference, Lancaster, UK. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/252986108

Dinh, J. V., Schweissing, E. J., Venkatesh, A., Traylor, A. M., Kilcullen, M. P., Perez, J. A., & Salas, E. (2021). The study of teamwork processes within the dynamic domains of healthcare: A systematic and saxonomic review. Frontiers in Communication, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.617928

Donche, V., & Van Petegem, P. (2011). Teacher educators’ conceptions of learning to teach and related teaching strategies. Research Papers in Education, 26(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2011.561979

Eagan, K., Stolzenberg, E. B., Lozano, J. B., Aragon, M. C., Suchard, M. R., & Hurtado, S. (2014). Undergraduate teaching faculty: The 2013–2014 HERI faculty survey. Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA. https://www.heri.ucla.edu/monographs/HERI-FAC2014-monograph.pdf

Ellis, T., & Hafner, W. (2008). Building a framework to support project-based collaborative learning experiences in an asynchronous learning network. Interdisciplinary Journal of Knowledge and Learning Objects, 4(1), 167–190. https://doi.org/10.28945/373

Flin, R., & O’Connor, P. (2017). Safety at the sharp end: A guide to non-technical skills. CRC Press.

Gokhale, A. A. (1995). Collaborative learning enhances critical thinking. Journal of Technology Education, 7(1), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.21061/jte.v7i1.a.2

Hampton, D. C., & El-Mallakh, P. (2017). Opinions of online nursing students related to working in groups. Journal of Nursing Education, 56(10), 611–616. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20170918-06

Hekmat, S. N., Dehnavieh, R., Rahimisadegh, R., Kohpeima, V., & Jahromi, J. K. (2015). Team attitude evaluation: An evaluation in hospital committees. Materia Socio-Medica, 27(6), 429–433. https://doi.org/10.5455/msm.2015.27.429-433

Hughes, A. M., Gregory, M. E., Joseph, D. L., Sonesh, S. C., Marlow, S. L., & Lacerenza, C. N. (2016). Saving lives: A meta-analysis of team training in healthcare. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(9), 1266–1304. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000120

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. (2007). The state of cooperative learning in postsecondary and professional settings. Educational Psychology Review, 19(1), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9038-8

Kebritchi, M., Lipschuetz, A., & Santiague, L. (2017). Issues and challenges for teaching successful online courses in higher education: A literature review. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 46(1), 4–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239516661713

Khalil, H., & Ebner, M. (2017). Using electronic communication tools in online group activities to develop collaborative learning skills. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 5(4), 529–536. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2017.050401

Kilgo, C. A., Sheets, J. K., & Pascarella, E. T. (2015). The link between high-impact practices and student learning: Some longitudinal evidence. Higher Education, 69(4), 509–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9788-z

Kilgour, P., & Northcote, M. (2018, June 25–29). Online learning in higher education: Comparing teacher and learner perspectives [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of EdMedia: World Conference on Educational Media and Technology, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/184450/

Koehler, M. J., Mishra, P., & Cain, W. (2013). What is technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK)? Journal of Education, 193(3), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205741319300303

Kossaify, A., Hleihel, W., & Lahoud, J. C. (2017). Team-based efforts to improve quality of care, the fundamental role of ethics, and the responsibility of health managers: Monitoring and management strategies to enhance teamwork. Public Health, 153, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.08.007

Krueger, R. A. (2014). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. Sage Publications.

Kurucay, M., & Inan, F. A. (2017). Examining the effects of learner-learner interactions on satisfaction and learning in an online undergraduate course. Computers & Education, 115, 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.06.010

LaBeouf, J. P., Griffith, J. C., & Roberts, D. L. (2016). Faculty and student issues with group work: What is problematic with college group assignments and why? Journal of Education and Human Development, 5(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.15640/jehd.v5n1a2

Le, H., Janssen, J., & Wubbels, T. (2018). Collaborative learning practices: Teacher and student perceived obstacles to effective student collaboration. Cambridge Journal of Education, 48(1), 103–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764x.2016.1259389

Lim, F. P. (2017). An analysis of synchronous and asynchronous communication tools in e-learning. Advanced Science and Technology Letters, 143(46), 230–234. https://doi.org/10.14257/astl.2017.143.46

Lock, J., & Johnson, C. (2015). Triangulating assessment of online collaborative learning. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 16(4), 61–70. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1143800.

Madden, T. J., Ellen, P. S., & Ajzen, I. (1992). A comparison of the theory of planned behavior and the theory of reasoned action. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167292181001

Marbach-Ad, G., Rietschel, C. H., Saluja, N., Carleton, K. L., & Haag, E. S. (2016). The use of group activities in introductory biology supports learning gains and uniquely benefits high-achieving students. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 17(3), 360–369. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v17i3.1071

Mast, L. J., & Gambescia, S. F. (2015). Assessing online education and accreditation for healthcare management programs. Journal of Health Administration Education, 32(4), 427–467. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1763641084?pq-origsite=gscholar.

McNeill, M., Gosper, M., & Xu, J. (2012). Assessment choices to target higher order learning outcomes: The power of academic empowerment. Research in Learning Technology, 20(3), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v20i0.17595

National Association of Colleges and Employers. (2019). Job outlook 2020. National Association of Colleges and Employers. http://www.naceweb.org

National Research Council. (2012). Education for life and work: Developing transferable knowledge and skills in the 21st century. The National Academies Press. https://www.nap.edu/resource/13398/dbasse_070895.pdf

Oyarzun, B., Barreto, D., & Conklin, S. (2018). Instructor social presence effects on learner social presence, achievement, and satisfaction. TechTrends, 62(6), 625–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-018-0299-0

Pandya, B., Patterson, L., & Cho, B. (2021). Pedagogical transitions experienced by higher education faculty members–“Pre-Covid to Covid”. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JARHE-01-2021-0028/full/html

Poulin, R., & Straut, T. T. (2016). WCET distance education enrollment report 2016: Utilizing U.S. Department of Education data. Babson Survey Research Group. https://wcet.wiche.edu/sites/default/files/WCETDistanceEducationEnrollmentReport2016.pdf

Rahman, M. S. (2016). The advantages and disadvantages of using qualitative and quantitative approaches and methods in language “testing and assessment” research: A literature review. Journal of Education and Learning, 6(1), 102–112. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v6n1p102

Rezaei, A. (2017). Features of successful group work in online and physical courses. Journal of Effective Teaching, 17(3), 5–22. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1175769.pdf.

Riebe, L., Girardi, A., & Whitsed, C. (2016). A systematic literature review of teamwork pedagogy in higher education. Small Group Research, 476(6), 619–664. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496416665221

Rienties, B., Brouwer, N., & Lygo-Baker, S. (2013). The effects of online professional development on higher education teachers’ beliefs and intentions towards learning facilitation and technology. Teaching and Teacher Education, 29, 122–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.09.002

Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C. M., & Ormston, R. (2013). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Sage Publications.

Robinson, H. A., Kilgore, W., & Warren, S. J. (2017). Care, communication, learner support: Designing meaningful online collaborative learning. Online Learning, 21–51(4), 29.

Rovai, A. P. (2004). A constructivist approach to online college learning. The Internet and Higher Education, 7(2), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2003.10.002

Sadaf, A., Newby, T. J., & Ertmer, P. A. (2012). Exploring preservice teachers’ beliefs about using web 2.0 technologies in K-12 classroom. Computers & Education, 59(3), 937–945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.04.001

Sadaf, A., Newby, T. J., & Ertmer, P. A. (2016). An investigation of the factors that influence preservice teachers’ intentions and integration of web 2.0 tools. Educational Technology Research and Development, 64(1), 37–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-015-9410-9

Sadeghi, H., & Kardan, A. A. (2015). A novel justice-based linear model for optimal learner group formation in computer-supported collaborative learning environments. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 436–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.020

Salas, E., Zajac, S., & Marlow, S. L. (2018). Transforming health care one team at a time: Ten observations and the trail ahead. Group & Organization Management, 43(3), 357–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601118756554

Santos, J., Figueiredo, A. S., & Vieira, M. (2019). Innovative pedagogical practices in higher education: An integrative literature review. Nurse Education Today, 72, 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.10.003

Scager, K., Boonstra, J., Peeters, T., Vulperhorst, J., & Wiegant, F. (2016). Collaborative learning in higher education: Evoking positive interdependence. CBE Life Sciences Education, 15(4), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-07-0219

Shaw, R. S. (2013). The relationships among group size, participation, and performance of programming language learning supported with online forums. Computers & Education, 62(1), 196–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.11.001

Silverman, D. (2013). Doing qualitative research: A practical handbook. Sage Publications.

Smith, A. R. (2018). Managing the team project process: Helpful hints and tools to ease the workload without sacrificing learning objectives. e-Journal of Business Education and Scholarship of Teaching, 12(1), 73–87. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1183301.pdf.

Springer, L., Stanne, M. E., & Donovan, S. S. (1999). Effects of small-group learning on undergraduates in science, mathematics, engineering, and technology: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 69(1), 21–51. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543069001021

Stake, R. E. (2006). Multiple case study analysis. Guilford Press.

State University System of Florida. (2019). Online education annual report 2018. https://www.flbog.edu/wp-content/uploads/FINAL-2018-Annual-Report.pdf

Stephens, G. E., & Roberts, K. L. (2017). Facilitating collaboration in online groups. Journal of Educators Online, 14(1), 1–16. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1133614.pdf.

Teo, T., & Lee, C. B. (2010). Explaining the intention to use technology among student teachers: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Campus-Wide Information System, 27(2), 60–67.

Ünal, E. (2020). Exploring the Effect of Collaborative Learning on Teacher Candidates’ Intentions to Use Web 2.0 Technologies. International Journal of Contemporary Educational Research, 7(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.33200/ijcer.736876

van Rooij, S. W., & Zirkle, K. (2016). Balancing pedagogy, student readiness and accessibility: A case study in collaborative online course development. The Internet and Higher Education, 28, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.08.001

Vercellone-Smith, P., Jablokow, K., & Friedel, C. (2012). Characterizing communication networks in a web-based classroom: Cognitive styles and linguistic behavior of self-organizing groups in online discussions. Computers & Education, 59(2), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.01.006

Vlachopoulos, P., Jan, S. K., & Buckton, R. (2020). A case for team-based learning as an effective collaborative learning methodology in higher education. College Teaching, 69(2), 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2020.1816889

Wade, C. E., Cameron, B. A., Morgan, K., & Williams, K. (2016). Key components of online group projects: Faculty perceptions. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 17(1), 33–56. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1142966.

Weaver, S. J., Dy, S. M., & Rosen, M. A. (2014). Team-training in healthcare: A narrative synthesis of the literature. BMJ Quality & Safety, 23(5), 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001848

Webb, N. M. (1994). Group collaboration in assessment: Competing objectives, processes, and outcomes. CRESST/University of California. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737017002239

Wingo, N. P., Ivankova, N. V., & Moss, J. A. (2017). Faculty perceptions about teaching online: Exploring the literature using the technology acceptance model as an organizing framework. Online Learning, 21(1), 15–35. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v21i1.761

Wise, A. F., Saghafian, M., & Padmanabhan, P. (2012). Towards more precise design guidance: Specifying and testing the functions of assigned student roles in online discussions. Educational Technology Research and Development, 60(1), 55–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-011-9212-7

Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: design and methods (6th ed.). Sage Publications.

Zawacki-Richter, O., Baecker, E. M., & Vogt, S. (2009). Review of distance education research (2000 to 2008): Analysis of research areas, methods, and authorship patterns. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 10(6), 21–50. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v10i6.741

Zygouris-Coe, V. (2012, July 5–7). Collaborative learning in an online teacher education course: Lessons learned [Paper presentation]. Readings in Technology in Education: Proceedings of the 12th ICICTE, Rhodes, Greece. http://www.icicte.org/Proceedings2012/Papers/08-4-Zygouris-Coe.pdf

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Karen L. Valaitis: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing original draft; Holly Ellis: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing; Nancy B. Hastings: Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing; Byron Havard: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Declaration of interest

None

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Valaitis, K.L., Ellis, H., Hastings, N.B. et al. The influence of personal attitude on instructor intent to integrate online collaborative activities. Educ Inf Technol 27, 5277–5299 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10814-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10814-7