Abstract

Background

Limited information is available about patterns of healthcare utilization for prevalent gastrointestinal conditions and their link to symptom burden.

Aim

To identify patterns of healthcare utilization among outpatients with highly prevalent gastrointestinal conditions and define the link between healthcare utilization, symptom burden, and disease group.

Methods

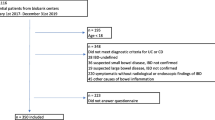

We randomly selected patients from the gastroenterology outpatient clinic at Princess Alexandra Hospital who had chronic gastrointestinal conditions such as constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C, n = 101), diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D, n = 101), mixed IBS (n = 103), inflammatory bowel disease with acute flare (n = 113), IBD in remission (n = 103), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (n = 102). All had presented at least 12 months before and had a 12-month follow-up after the index consultation. Healthcare utilization data were obtained from state-wide electronic medical records over a 24-month period. Intensity of gastrointestinal symptoms was measured using the validated Structured Assessment of Gastrointestinal Symptoms (SAGIS) Scale. Latent class analyses (LCA) based on healthcare utilization were used to identify distinct patterns of healthcare utilization among these patients.

Results

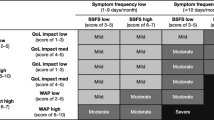

LCA revealed four distinct healthcare utilization patterns across all diagnostic groups: Group A: Emergency department utilizers, Group B: Outpatient focused care utilizers, Group C: Inpatient care utilizers and Group D: Inpatient care and emergency department utilizers. LCA groups with high emergency utilization were characterized by high gastrointestinal symptom burden at index consultation regardless of condition (Mean (standard deviation)) SAGIS score Group A: 24.63 (± 14.11), Group B: 19.18 (± 15.77), Group C: 22.48 (± 17.42), and Group D: 17.59 (± 13.74, p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Distinct healthcare utilization patterns across highly prevalent gastrointestinal conditions exist. Symptom severity rather than diagnosis, likely reflecting unmet clinical need, defines healthcare utilization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The increasing prevalence of chronic gastrointestinal (GI) conditions, including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) [1], inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [2], and functional GI disorders including irritable bowel disorders [3], puts pressure on healthcare systems. In relation to the burden that such conditions present, most studies capture the prevalence, determine total healthcare expenditure and quantify the impact of specific conditions on quality of life to assess the overall burden on society [4]. Healthcare needs are highly variable even among distinct disease groups such as IBD, GERD, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS); most—but not all—patients with GERD or IBS can be effectively managed in the primary care setting [5]. However, healthcare costs are frequently driven upward by small numbers of patients with intense utilization of services who are not effectively managed in the primary care setting and are ultimately referred to specialists or receive an excessive number of services. It is assumed that these patients are typically the most complex patient populations [6]. The identification and characterization of distinct patient cohorts with high healthcare utilization can help to identify those with a high, currently unmet need, to develop targeted measures to address their healthcare needs more effectively. Recent data suggest that patients with IBS with frequent use of specialized GI-specific diagnostic tests and procedures are characterized by the presence of specific risk factors including depression, anxiety, somatization, and female sex [7]. However, very little is known about other highly prevalent GI conditions and the overall somatization of healthcare services when these patients are referred to specialists for management.

While most patients with chronic GI conditions are managed as outpatients, some require inpatient treatment; severe disease manifestations may even trigger unscheduled presentations to emergency departments. A significant proportion of emergency department presentations in the United States is attributable to GI disease, with more than 15.7 million visits reported in 2014 [8]. It is currently unknown whether specific patient cohorts with distinct patterns of healthcare utilization exist, and whether healthcare utilization patterns are linked to specific conditions. Furthermore, we know very little about the role of GI symptom severity in patients with chronic GI conditions and subsequent healthcare utilization. It can be hypothesized that patients with severe GI symptoms have an increased utilization of healthcare services and that specific conditions such as IBS are associated with increased numbers of hospital admissions.

We aimed to determine and compare healthcare utilization of patients with defined, highly prevalent GI conditions (IBS, IBD, and GERD) and define the links between healthcare utilization, symptom burden, and disease group.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study, approved by the Metro South Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number HREC/18/QPAH/363).

Participants

All outpatients seen at the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the Princess Alexandra Hospital who were able to read and understand the Structured Assessment of Gastrointestinal Symptoms Scale (SAGIS) completed this GI assessment tool as part of routine clinical care. The Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the Princess Alexandra Hospital is a large, public funded tertiary/quaternary service provider in Brisbane, Australia with a catchment of a population of approximately 2 million. All patients were entitled to receive clinical services free of charge provided that they are referred by a primary care physician or specialist from outside the state-funded public hospital system. In addition, patients can be referred for specialist outpatient services for ongoing care after presentation for emergency services at one of the state funded hospital-based emergency departments. Standardized criteria were applied to categorize the urgency of the referral. For routine referrals, primary care physicians were required to have initiated (and documented in the referral letter) prior to the referral appropriate treatments (e.g., life-style management or dietary interventions, or treatment with proton pump inhibitors), but symptoms had not appropriately responded or there were other concerns. Eighty five percent of all ‘new' patients were seen within 30 to 90 days after receiving the referral. We randomly selected patients from those who had an index consultation between November 2016 and June 2018 (and had subsequently completed SAGIS forms) utilizing the Microsoft Excel® RAND function, and those who had presented and completed SAGIS at least 12 months earlier and had > 12 months of follow-up after the index consultation. We selected at least 100 patients, each with the following main clinical diagnoses: IBD in remission (for patients with Crohn’s disease defined by a Crohn’s Disease Activity Index score < 150 or patients with ulcerative colitis defined by a partial Mayo score < 1) and active IBD defined by the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index and Mayo scores. Additionally, we included patients with IBS meeting the Rome III criteria (constipation-predominant IBS [IBS-C], diarrhea-predominant IBS [IBS-D], mixed IBS [constipation and diarrhea symptoms; IBS-M]), as well as those with GERD based on the Montreal classification [9] with response to PPI therapy or a pathologic reflux on 24 pH study.

Measures

Healthcare Utilization

We used the statewide integrated electronic medical record system to retrieve information on hospital admissions, length of hospital stay, gastroenterology and other medical and allied specialists outpatient department (e.g., hepatology, dermatology, rheumatology, nephrology, orthopedics, dietetics) consultations, diagnostic procedures (magnetic resonance imaging, computerized tomography, ultrasound), therapeutic day procedures (e.g., colonoscopy, upper GI endoscopy but not screening/surveillance), and emergency department presentations. Presentations were captured for a period of 24 months, including a period of 12 months before and 12 months after the index consultation. Furthermore, the average length of hospital stay in patients with at least one hospitalization was determined. We did not simply capture inpatient care linked/caused by the GI diagnosis (e.g., GERD) but captured all health services utilized by the respective patients.

Symptom Intensity

The intensity and impact of 22 GI symptoms was measured using the SAGIS, a validated instrument [10] and clinical tool. Responses were given on a 5-point Likert scale (0 to 4, with a maximum total score of 88) from “no problem,” “mild problem,” (can be ignored when you do not think about it), “moderate problem” (cannot be ignored, but does not influence daily activities), “severe problem” (influencing concentration on daily activities), to “very severe problem” (markedly influences daily activities and/or requires rest). The SAGIS also includes questions on the presence of selected non-GI symptoms including headache, chronic fatigue, back pain, sleep disturbances, depression and anxiety. Patients also identified their first- and second-most important health problems. The information captured with SAGIS provides clinicians guidance in relation to the symptom burden and captures over time symptom responses to therapy. For the purpose of this study GI symptom burden was classified according to SAGIS scores of mild (0–15), moderate (16–30), severe (31–45), and very severe (≥ 46). SAGIS is completed by > 95% of all patients presenting to the department.

Data were available on an initial sample of 35,000 consecutive patients presenting to the Department of Gastroenterology between November 2016 and June 2018. Key symptom parameters of the selected subgroups, including severity of symptoms, age, and sex, were reviewed and compared with the initial sample to confirm that the random selection was comparable to and representative of the initial sample of consecutive patients. This information was independently reviewed by author Ayesha Shah to ensure the selected sample data were representative of the healthcare pathways by the larger cohort of patients with these disorders presenting to the gastroenterology outpatient department at Princess Alexandra Hospital.

Statistical Analysis

The SAGIS database was linked with the Princess Alexandra Hospital integrated electronic medical record system. Descriptive statistics for quantitative variables are reported by mean and standard deviation (SD); categorical variables were described as the sample size (N) and percentage in the category. While skewed distributions are sometimes described in terms of percentiles, for some measures in this study the distribution includes sufficient zero counts that the median is insensitive to small-to-moderate changes in distributions. Hence, mean/SD are used in this report. Disease groups were compared using analysis of variance for all quantitative resource utilization. Formal statistical inference employed the nonparametric bootstrap using 2000 bootstrap samples due to non-normal distribution of outcome measures. Post-hoc comparisons of groups were performed with Bonferroni correction. Correlations were performed on the 12-month pre-index SAGIS intensity scores and healthcare utilization indices (hospital admissions, length of hospital stay, gastroenterology and other medical and allied specialists outpatient department consultations, diagnostic procedures, therapeutic day procedures, and emergency department presentations) using Spearman rank correlations. Descriptive statistics were used to report by groups on number and types of other specialist outpatient encounters and procedures. A sample of n = 96 per study group yields statistical power 0.9 at the 0.05 (2-tailed) level of statistical significance for a maximum difference between disease groups corresponding to a Cohen’s d of 0.5. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 24.0. As multiple hypothesis tests have been conducted, all at the 0.05 level, we regard these findings as needing replication.

Naturally occurring clusters of patients were sought using latent profile models, with profiles formed from measures of healthcare resource utilization over a 24-month period. Removal of multivariate outliers were done prior to undertaking the classification analysis to avoid allowing a small number of multivariate outliers to disproportionately influence the cluster solution. All measures were standardized to a mean 0, SD 1 scale to avoid any measure having undue influence due to its measurement. The number of latent clusters was sought from solutions between two and six clusters, inclusive. The solution selection criteria were pre-set as minimum/minimal change in Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and by inspection of whether moving from a simpler to a more complex solution represented a substantial restructuring of clusters or a small number of individuals moving clusters. Both the change in BIC and the change in cluster membership were revaluated after each new cluster solution was created, starting with a 2-cluster solution and ending with a 6-cluster solution. Based on the BIC change statistics and change in cluster membership, the four-cluster solution was adopted. Clusters were then compared with respect to individual measures of healthcare resource utilization and factors within the group that are potential drivers of the behaviors, including age, sex, SAGIS intensity scores, and diagnostic groups. Latent profile models were fitted as structural equation models in the Stata software (v17).

Results

Baseline Demographics

Overall, the non-identified data from 623 patients were included in this study. Mean age was 49.4 years (SD 16.2 years) and 62% were female. Patient characteristics per diagnostic group are shown in Table 1. The mean age of patients in each diagnostic group was in the forties or fifties, with more females, except for inactive IBD where there were slightly fewer females than males.

Healthcare Resource Utilization Over 24 Months

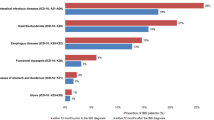

Healthcare resource utilization over a 24-month period for the IBS and IBD subgroups, as well as for patients with GERD, is presented in Table 2. Number of hospital admissions was similar across all patient groups. In terms of number of days in hospital and number of procedures, IBS-D was not different to IBD and GERD, but patients with IBS-C (p < 0.05) and IBS-M (p < 0.05) had significantly fewer hospital stay days than those with active IBD (Table 2). Patients with active and inactive IBD had a similar number of hospital days and therapeutic procedures (Table 2). In terms of gastroenterology outpatient department visits, all IBS subgroups were not different from inactive IBD and GERD but had significantly fewer visits than active IBD (Table 2). Utilization of other specialist outpatient consultations was significantly higher in IBS-D compared with both active and inactive IBD (Table 2). Analyzing the number of emergency department presentations did not reveal statistically significant differences between IBS and even active IBD (Table 2).

Symptom Severity as Measured by SAGIS

Figure 1 shows the mean SAGIS scores 12 months before and 12 months after the index consultation. In the year before the index consultation, IBS subgroups reported a significantly higher total GI symptom burden compared with active and inactive IBD (Fig. 1); however, total GI symptom burden in IBS-D and IBS-M was not significantly different to GERD. In the year after the index consultation, IBS subgroups reported a significantly higher total GI symptom burden compared with inactive IBD, although IBS-D and IBS-M were not significantly different to active IBD and GERD (Fig. 1). Patients with IBS-C reported a significantly higher total GI symptom burden compared with both active and inactive IBD and GERD (Fig. 1).

SAGIS GI symptom burden among patient groups in the year before and the year after the index consultation. Note: Margins sharing a letter in the group label are not statistically significantly different (p > 0.05). GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; GI, gastrointestinal; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IBS-C, constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-D, diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-M, mixed irritable bowel syndrome; SAGIS, Structured Assessment of Gastrointestinal Symptoms Scale

Naturally occurring clusters of patients were sought using latent profile models, with profiles formed from measures of healthcare resource utilization over a 24-month period.

Latent Class Analysis Subgroups Based on Healthcare Utilization

Table 3 shows the findings of naturally occurring clusters of patients using latent profile models, with profiles formed from measures of healthcare resource utilization over a 24-month period. Latent class analysis based on healthcare utilization yielded four latent class groups (Table 4) that included 423 out of 623 patient data sets. Group A had a higher (i.e., more than twice the average) number of unscheduled emergency department presentations and a high GI symptom burden, Group B was the largest group and was characterized by frequent (i.e., more than twice the average) “standard” outpatient department consultations, Group C included patients with increased inpatient care and Group D were patients with increased inpatient care and increased emergency department presentations. In Group A, patients with IBS were overrepresented (57.1%, n = 40) versus organic disease (42.9%, n = 30) (Table 4). In Group B, functional and organic diseases were balanced (IBS 46.9%, n = 128 vs IBD and GERD 53.1%, n = 145; Table 4). Group C were predominantly patients with organic disease (IBD and GERD 59.6%, n = 28 vs IBS 40.4%, n = 19; Table 4). Group D were patients with organic GI disease (IBD and GERD 86.4%, n = 19 vs IBS 13.6%, n = 3; Table 4).

Association Between GI Symptom Intensity and Healthcare Resource Utilization

Across individual disease cohorts, pre-index consultation SAGIS intensity scores were statistically significantly correlated with number of emergency presentations (r = 0.34, p < 0.001), hospital admissions (r = 0.18, p < 0.001), other specialist outpatient department visits (r = 0.17, p < 0.001), and number of diagnostic tests (r = 0.14, p = 0.0004).

Discussion

This study aimed to characterize and compare healthcare utilization and identify specific patterns of utilization of in- and outpatient services or emergency services among patients with highly prevalent conditions such as IBD (with or without acute flare), IBS (and its subtypes), and GERD. Overall, all of the main diagnostic groups had very similar emergency department utilization, while the number of specialist gastroenterology outpatient consultations was significantly higher in patients with active IBD as compared to all other groups. Exploring distinct patterns of health care utilization, latent class analysis revealed four distinct patterns of healthcare utilization across the heterogenous gastroenterological disease groups: Group A were patients with a high (i.e., more than twice the average) rate of emergency department presentations, Group B were patients using mainly elective outpatient services, Group C were patients with a high rate of hospitalizations without utilization of emergency services and Group D comprised patients with a high rate of inpatient and emergency services. While Groups A and B included patients with all conditions, patients with IBD were overrepresented in Groups C and D. Consistently high symptom severity, as measured by the standardized symptom questionnaire SAGIS and not specific diagnoses (e.g., IBS, IBD, GERD), was associated with high utilization of emergency services.

In most countries, healthcare expenditure for IBS is high. In any given year, almost half of patients diagnosed with IBS will incur some direct medical and gastroenterology healthcare costs, with annual international estimates per patient of US$742–7547 in the United States, £90–316 in the United Kingdom, €567–862 in France, and €791 in Germany [11]. While various studies have assessed and compared healthcare costs for IBS [11], IBD [12], and GERD [13], there are limited data on the pattern and relative intensity of healthcare utilization among patients seen by specialists. Nevertheless, considerable numbers of patients are referred by their primary care physicians for treatment by specialists. Thus, it is evident that even within defined disease groups of patients with IBS for example, there are considerable differences in healthcare needs. It is also known that healthcare costs are frequently driven by a small number of patients within one disease group who require intense utilization of services. These patients are typically the most complex patient populations [6]. Indeed, not everyone with IBS symptoms seeks healthcare services, and consultation rates are highly variable. In the Australian public healthcare system, access to services is not constrained by service fees payable by patients. If patients seen by primary care physicians require input or specialized services by Gastroenterologists, they are referred to a public hospital and patients receive services free of charge within the public hospital system; thus, our study provides data that are not confounded by the funding constraints patients face. We found that during a 2-year period, patients with IBS-D were hospitalized on average for 6 days, and this was not different to patients with chronic organic conditions such as IBD and GERD. Similarly, patients with IBS were not different to patients with active IBD and GERD in terms of presentations to emergency departments, and symptom severity was closely associated with emergency presentation across all disease cohorts (r = 0.34, p < 0.001).

On the other hand, latent class analysis revealed that most patients (65%) required mainly elective outpatient services. However, the second-largest group (17%) consisted of patients with a high rate of emergency presentations (without subsequent hospital admissions). While we expected to see patients with active IBD represent a considerable portion of patients in Group A, we also saw a similar proportion of patients with IBS in the same group. Presentations to emergency departments are frequently seen as a marker of an unmet clinical need [14]. This suggests that a considerable unmet clinical need exists in subgroups of patients with IBS, IBD, and GERD, and that these patients are characterized by high GI symptom scores.

Given that IBS is not life threatening, the high utilization of emergency services by these patients highlights the failure of current treatment approaches to effectively manage symptoms. Indeed, response rates to established pharmacologic therapies rarely exceed placebo responses by more than 10% or 15% [15, 16] There is also good evidence that lifestyle and dietary interventions are beneficial in some patients [17], and that probiotics and prebiotics can improve symptoms [18]. Thus, appropriate management of GI symptoms for these patients is most likely required to avoid unscheduled emergency department visits and overall healthcare resource utilization. Furthermore, allocation of healthcare services, the development of prioritization criteria for access to services, and the development of novel services or treatment should take symptom severity or the impact of symptoms on quality of life into account. This may provide an opportunity to target severely affected patients with IBS for example, with specifically developed multiprofessional interventions [19] or new therapies [20] to improve patient outcomes and prevent unscheduled emergency presentations.

Although the well-established Rome criteria, now the gold standard for diagnosing IBS, provides a positive, symptom-based diagnosis alone, meaning costly diagnostic investigations and procedures are not required [20], many studies have found that patients with IBS have high utilization of gastroenterology and non-gastroenterology consultations, emergency presentations and diagnostic investigations [11, 21,22,23,24,25,26]. Indeed, a recent study from Europe reported that the largest direct cost driver for patients with IBS-C was emergency department presentations or even admissions [24]. While the patients in our study virtually all met the Rome criteria, our findings support accumulating evidence that diagnostic testing and procedures to rule out organic or structural abnormalities are widely used in spite of the Rome criteria, particularly in patients with severe manifestations. In regards to IBD we recognize that histologic data are ideal to define full remission of IBD, however in the routine clinical setting, histologic data are not available for all patients and reliance on histology would have resulted in a selection bias. In addition, from a clinical, regulatory or research perspective there is no single unified generally accepted definition for remission. Thus, the approach to use CDAI and Mayo scores reflects routine clinical practice.

New-onset and severe symptoms frequently drive healthcare seeking. Treatments usually target well-defined disease mechanisms (e.g., gastric acid in patients with GERD) to improve symptoms and are very effective in many patient groups. In contrast, in patients with so-called IBS, there is no obvious “underlying” cause of symptoms that can be identified in the routine clinical setting, and there are no treatments available that effectively improve symptoms and subsequently minimize healthcare utilization [27]. Many patients presenting with IBS have severe or very severe symptoms that substantially impair their quality of life [28], and these patients are known to have worse health-related quality of life than patients with other organic conditions such as GERD, diabetes mellitus, and end-stage kidney disease [29]. Even in primary care patients with a confirmed diagnosis of IBS, GI symptoms can interfere with performance at work [30], resulting in significant use of healthcare resources [31]. Clinical guidelines for highly prevalent GI disorders [32,33,34,35] highlight a rational, evidence-based use of healthcare resources covering a spectrum of mild to very severe manifestations with and without extraintestinal disease manifestations. Interestingly, our data show that the pattern of healthcare utilization is very similar in distinct, highly prevalent GI conditions, including various IBS types, and the common denominator for healthcare utilization, and utilization of emergency services in particular, is the severity of GI symptoms.

This study represents a novel approach to assesses patient needs and categorize patient cohorts based upon their health care utilization instead of diagnosis. This has several strengths, including the evaluation of a range of healthcare indices in the outpatient setting, the ability to match healthcare utilization data directly to symptom data using a validated instrument and electronic medical records, and the ability to study random samples of patients with selected highly prevalent GI conditions from a population of more than 2 million people living within the catchment of our health care organization who have free access to specialized healthcare services and who were seen as outpatients and subsequently recruited simply based on their residency in the hospital catchment area. All of these patients were initially managed and referred by a primary care physician. While a previous study found that 80% of population-based subjects with symptoms consistent with Rome I criteria of IBS sought medical care [36], it is unknown how many patients with IBS or GERD require a consultation with a specialist. In contrast, all patients with IBD requiring treatment with biologics will be referred to a specialist in order to receive subsidized (free of charge) treatment with biologics. While it is reasonable to assume that patients seen by a specialist are patients less responsive to therapy or more severe symptoms, it is unknown what proportion of patients with IBS, GERD, or IBD require to be referred to a specialist. In this context it is important to note that with the exception of biologics (which require a prescription by a specialist) all medications (e.g., prokinetics, proton pump inhibitors psychotropic medications) are available either as prescriptions (via primary care physician or the specialists) or over the counter (prokinetics, low dose proton pump inhibitors).

Thus, another strength is that our study population is representative of patients who fail to be successfully managed in the primary care setting. As a limitation it is likely that these patients have more severe disease manifestations than population based subjects and likely represent patients typically seen by gastroenterologists. In addition, only data from a single center was obtained, potentially limiting the extrapolation of the study results. It is also possible that symptom severity levels seen in GERD may reflect the older age of this group as they may have had symptoms for a longer duration. However, it is well established that the incidence of GERD increases with age, rising dramatically after 40 years of age. As another limitation, this is a retrospective, longitudinal cohort study and we did not capture primary care or alternative therapy utilization. Additionally, we did not adjust for other variables such as comorbidities, prior healthcare utilization, disease duration, and private health insurance status in an ANCOVA (analysis of covariance) model, which theoretically could have affected the outcome. This was because this information was not uniformly available for all patients. On the other hand, patients were randomly selected, and all had the same eligibility criteria for participation in this study. While the study design classifies patients with IBS based on the clinical presentation at the index consultation, the allocation of patients was not changed over time, even if symptom changes manifested over time. However, it is well recognized that the IBS-C and IBS-D phenotypes remain relatively stable over time, with shifts between IBS-C and IBS-D being rare [37]. We also did not explore overlap between IBS and GERD for example as only primary diagnosis were included. A future study could explore this further. Additionally, while the use of latent class analysis is novel in this study, it is descriptive and not predictive at an individual level. Nevertheless, it allows for categorization of patient cohorts that is not driven by any biases the investigator may have had.

The timing of the SAGIS administration (e.g., 12 months before and 12 months after the index consultation) did not necessarily correspond to each healthcare utilization visit. Moreover, specific causes of healthcare utilization (i.e., whether they were GI related or not) were not analyzed, including disease history and medical comorbidities.

In conclusion, among a random sample of patients with IBS, IBD, and GERD referred by primary care physicians for treatment by specialists, latent class analysis reveals distinct healthcare utilization patterns. A significant proportion of patients fall into the category of frequent emergency department consulters. These predominantly include patients with IBD and IBS, and approximately 10% of the patients with IBS-C were in the frequent emergency department consulter group. These patients were characterized by a high symptom burden, suggesting that poorly controlled symptoms are an important driver for excess healthcare utilization and emergency presentations. This may offer an opportunity to specifically target patients with severe disease manifestations (as reflected by the severity of GI symptoms) to reduce overall health care utilization and relieve the burden of disease and improve patient outcomes.

References

Richter JE, Rubenstein JH. Presentation and epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 2018;154:267–276.

Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Understanding and preventing the global increase of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2017;152:313–21.e2.

Sperber AD, Bangdiwala SI, Drossman DA et al. Worldwide prevalence and burden of functional gastrointestinal disorders, results of Rome Foundation global study. Gastroenterology 2021;160:99-114.e3.

Burisch J, Jess T, Martinato M et al. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:322–337.

Gikas A, Triantafillidis JK. The role of primary care physicians in early diagnosis and treatment of chronic gastrointestinal diseases. Int J Gen Med 2014;7:159–173.

Wammes JJG, Tanke M, Jonkers W et al. Characteristics and healthcare utilisation patterns of high-cost beneficiaries in the Netherlands: a cross-sectional claims database study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017775.

Lacy B, Ayyagari R, Guerin A et al. Factors associated with more frequent diagnostic tests and procedures in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2019;12:1–17.

Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC et al. Burden and cost of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic diseases in the United States: update 2018. Gastroenterology 2019;156:254–72.e11.

Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006 Aug;101(8):1900–20

Koloski NA, Jones M, Hammer J et al. The validity of a new Structured Assessment of Gastrointestinal Symptoms Scale (SAGIS) for evaluating symptoms in the clinical setting. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62:1913–1922.

Canavan C, West J, Card T. Review article: the economic impact of the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:1023–1034.

Park KT, Ehrlich OG, Allen JI et al. The cost of inflammatory bowel disease: an initiative from the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2020;26:1–10.

Gawron AJ, French DD, Pandolfino JE et al. Economic evaluations of gastroesophageal reflux disease medical management. Pharmacoeconomics 2014;32:745–758.

McKenzie H, Hayes L, White K et al. Chemotherapy outpatients’ unplanned presentations to hospital: a retrospective study. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:963–969.

Qin D, Yue L, Xue B, et al. Pharmacological treatments for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e15920.

Black CJ, Burr NE, Quigley EMM et al. Efficacy of secretagogues in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2018;155:1753–1763.

McKenzie YA, Bowyer RK, Leach H et al. British Dietetic Association systematic review and evidence-based practice guidelines for the dietary management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults (2016 update). J Hum Nutr Diet 2016;29:549–575.

Ford AC, Harris LA, Lacy BE et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics and antibiotics in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;48:1044–1060.

Bray N, Koloski NA, Jones MP et al. A multidisciplinary integrated treatment approach is superior to standard care for functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs): a case-control study [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2019;156:273.

Camilleri M. Management options for irritable bowel syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc 2018;93:1858–1872.

Longstreth GF, Yao JF. Irritable bowel syndrome and surgery: a multivariable analysis. Gastroenterology 2004;126:1665–1673.

Levy RL, Von Korff M, Whitehead WE et al. Costs of care for irritable bowel syndrome patients in a health maintenance organization. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:3122–3129.

Flik CE, Laan W, Smout AJPM et al. Comparison of medical costs generated by IBS patients in primary and secondary care in the Netherlands. BMC Gastroenterol 2015;15:168.

Tack J, Stanghellini V, Mearin F et al. Economic burden of moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome with constipation in six European countries. BMC Gastroenterol 2019;19:69.

Gudleski GD, Satchidanand N, Dunlap LJ et al. Predictors of medical and mental health care use in patients with irritable bowel syndrome in the United States. Behav Res Ther 2017;88:65–75.

Van den Houte K, Carbone F, Pannemans J et al. Prevalence and impact of self-reported irritable bowel symptoms in the general population. United European Gastroenterol J 2019;7:307–315.

Moayyedi P, Simrén M, Bercik P. Evidence-based and mechanistic insights into exclusion diets for IBS. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;17:406–413.

Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Boyce PM. The impact of functional gastrointestinal disorders on quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:67–71.

Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne A et al. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology 2000;119:654–660.

Faresjö Å, Walter S, Norlin AK et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms - an illness burden that affects daily work in patients with IBS. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2019;17:113.

Paré P, Gray J, Lam S et al. Health-related quality of life, work productivity, and health care resource utilization of subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: Baseline results from logic (longitudinal outcomes study of gastrointestinal symptoms in Canada), a naturalistic study. Clin Ther 2006;28:1726–1735.

Layer P, Andresen V, Pehl C, et al. [Irritable bowel syndrome: German consensus guidelines on definition, pathophysiology and management]. Z Gastroenterol 2011;49:237–93.

Fock KM, Talley N, Goh KL et al. Asia-Pacific consensus on the management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: an update focusing on refractory reflux disease and Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 2016;65:1402–1415.

Modlin IM, Hunt RH, Malfertheiner P et al. Diagnosis and management of non-erosive reflux disease – the Vevey NERD Consensus Group. Digestion 2009;80:74–88.

Pieper C, Haag S, Gesenhues S et al. Guideline adherence and patient satisfaction in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disorders – an evaluation study. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:17.

Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Boyce PM. Epidemiology and health care seeking in the functional GI disorders: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol Suppl 2002;97(9):2290–2299.

Chira A, Filip M, Dumitraşcu DL. Patterns of alternation in irritable bowel syndrome. Clujul Med 2016;89:220–223.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support with data review and data extraction by Teressa Hansen, RN and Kate Virgo RN, as well as the support in study conceptualization, methodology and data validation by Amanda Halliday. Editorial services were provided by Stephanie J. Rippon, MBio, and Rebecca Fletcher, BA (Hons), of Complete HealthVizion, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA and funded by Allergan plc (prior to acquisition by AbbVie Inc.).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This study was sponsored by Allergan plc, Dublin, Ireland (prior to acquisition by AbbVie Inc.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: IK, GH. Data curation: NK, MPJ, GH. Formal analysis: NK, AS, MPJ, GH. Funding acquisition: IK, GH. Investigation: NK, AS, IK, RBJ, GH. Methodology: NK, AS, IK, RBJ, NJT, MPJ, GH. Project administration: NK, IK. Resources: GH. Software: NK. Supervision: NK, IK, GH. Validation: NK, AS, IK, RBJ, MPJ, GH. Writing—original draft: NK, IK, GH. Writing—review and editing: NK, AS, IK, RBJ, NJT, MPJ, GH.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

Natasha Koloski, Ayesha Shah, Ronen Ben Jacob, and Michael P. Jones disclose no conflicts. Iain Kaan is a former employee of AbbVie. Nicholas J Talley's disclosures include Intrinsic Medicine (2022) (human milk oligosaccharide), Alimentry (2023) (gastric mapping), Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (fiber and laxation) (2024), outside the submitted work. In addition, Dr. Talley has a patent Nepean Dyspepsia Index (NDI) 1998, a patent Licensing Questionnaires Talley Bowel Disease Questionnaire licensed to Mayo/Talley, “Diagnostic marker for functional gastrointestinal disorders” Australian Provisional Patent Application 2021901692, “Methods and compositions for treating age-related neurodegenerative disease associated with dysbiosis” US Patent Application No. 63/537,725. Financial support: Dr. Talley is supported by funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) to the Centre for Research Excellence in Digestive Health and he holds an NHMRC Investigator grant and a research grant from Defence. Gerald Holtmann received unrestricted educational support from the Falk Foundation. Research support was provided via the Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane by GI Therapies Pty Ltd, Takeda Development Center Asia, Pty Ltd, Eli Lilly Australia Pty Ltd, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, MedImmune Ltd, Celgene Pty Ltd, Celgene International II Sarl, Gilead Sciences Pty Ltd, Quintiles Pty Ltd, Vital Food Processors Ltd, Datapharm Australia Pty Ltd Commonwealth Laboratories, Pty Ltd, Prometheus Laboratories, FALK GmbH & Co KG, Nestle Pty Ltd, Mylan, and Allergan (prior to acquisition by AbbVie Inc.). Dr. Holtmann is also a patent holder for a biopsy device to take aseptic biopsies (US 20150320407 A1).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

An invited commentary on this article is available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-024-08298-9.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koloski, N., Shah, A., Kaan, I. et al. Healthcare Utilization Patterns: Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Inflammatory Bowel Disease, and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Dig Dis Sci 69, 1626–1635 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-024-08297-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-024-08297-w