Abstract

Introduction

The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) among US Hispanics is rising. Adoption of an American diet and/or US acculturation may help explain this rise.

Aims

To measure changes in diet occurring with immigration to the USA in IBD patients and controls, and to compare US acculturation between Hispanics with versus without IBD. Last, we examine the current diet of Hispanics with IBD compared to the diet of Hispanic controls.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of Hispanic immigrants with and without IBD. Participants were recruited from a university-based GI clinic. All participants completed an abbreviated version of the Stephenson Multi-Group Acculturation Scale and a 24-h diet recall (the ASA-24). Diet quality was calculated using the Healthy Eating Index (HEI-2010).

Results

We included 58 participants: 29 controls and 29 IBD patients. Most participants were Cuban or Colombian. Most participants, particularly those with IBD, reported changing their diet after immigration (72% of IBD and 57% of controls). IBD participants and controls scored similarly on US and Hispanic acculturation measures. IBD patients and controls scored equally poorly on the HEI-2010, although they differed on specific measures of poor intake. IBD patients reported a higher intake of refined grains and lower consumption of fruits, whereas controls reported higher intake of empty calories (derived from fat and alcohol).

Conclusion

The majority of Hispanics change their diet upon immigration to the USA and eat poorly irrespective of the presence of IBD. Future studies should examine gene–diet interactions to better understand underlying causes of IBD in Hispanics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic immune-mediated disease that affects approximately 1 million people in the USA and is on the rise globally [1, 2]. Studies examining the incidence of IBD indicate that immigrants arriving to countries where IBD has a high prevalence adopt a similar prevalence as that of the native population [3, 4]. This “immigrant effect” is observed primarily in immigrants moving to Westernized countries [3]. Similarly, the incidence of IBD is rising among Hispanics migrating to the USA compared to those remaining in Latin America [5]. In our previous study, we observed that, within one US-born generation, Hispanics resembled the IBD phenotype of White Americans [5]. These rapid shifts observed in IBD prevalence and presentation among immigrant groups coming to the USA support the strong role of the environment in IBD [5,6,7]. Therefore, the study of lifestyle changes that occur with acculturation among Hispanic immigrants represents a natural experiment to identify novel contributors to the rising prevalence of IBD.

Epidemiologic studies suggest that diet plays a role in the development of IBD. Diets high in animal protein, particularly red meats, and low in fruits and vegetables are characteristic of a “Western” diet and are associated with IBD in large prospective datasets [8, 9]. We hypothesize that dietary acculturation to a Western diet pattern is likely a major contributor to the development of IBD among Hispanic immigrants. Acculturation to US cultural norms, including dietary acculturation, is a major determinant of certain chronic diseases among Hispanic immigrants. Several studies, including the Hispanic HANES, the NHANES III, and the Study of Latinos/Hispanic Community Health Study, indicate that hypertension, metabolic disease, obesity, and cardiovascular disease are associated with higher levels of acculturation to US culture among Hispanics [8, 9]. However, the acculturation instruments used in many epidemiological datasets are based on a unidimensional framework where Hispanic and US cultural endorsement are cast as opposing ends of a single dimension [10]. Validated measures of acculturation are more likely to assess Hispanic and US cultural influences separately, an approach that is more consistent with state-of-the-art acculturation models [11]. A study examining acculturation in Hispanics with IBD, using construct-valid measures of acculturation, could help us understand the social determinants and contributors to the rise of IBD in this large and growing demographic group.

In the present study, we sought to determine the extent to which (a) Hispanics change their diet after US immigration compared to Hispanics without IBD; (b) acculturation, including dietary acculturation, differs between Hispanics with versus without IBD; and (c) diet quality, a method of nutritional assessment that evaluates dietary adherence to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, differs between Hispanics with versus without IBD [12]. Our study is the first to evaluate dietary adjustment occurring in Hispanics with IBD and the first to examine acculturation-related variables among Hispanic IBD patients and controls.

Methods

Study Design and Population

This study was conducted at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. We conducted a cross-sectional study on Hispanic immigrants. Healthy controls and IBD patients were recruited from the university’s GI clinic. IBD patients were followed at a tertiary referral center or at a public hospital safety net GI clinic. Healthy controls were also recruited from the GI clinic and were either clinic staff or relatives of patients who did not live in the same household and who met the study inclusion criteria.

IBD patients were included if they were adults (≥ 18 years of age), self-reported as Hispanic, were born in Latin America, and developed IBD symptoms after arriving in the US. All IBD patients were followed at GI clinics in South Florida, and their IBD was confirmed using endoscopic, histologic, and radiologic examinations. In addition, we included only patients who reported no changes in their diet or GI symptoms in the week prior to assessment. Healthy controls were included in the study if they were adults (≥ 18 years of age), self-reported as Hispanic, were born in Latin America, and reported not having any GI diseases or symptoms at the time of assessment.

Participant demographics, including gender, year of immigration, age at immigration, duration of residence in the USA, education level, and marital status were assessed as part of our survey instrument. Information regarding IBD type (Crohn’s versus ulcerative colitis), current medications, luminal disease location using Montreal Classification (proctitis, pancolitis, etc.), as well as history of abdominal surgeries was obtained at the time of dietary and acculturation data collection in IBD patients. This information was obtained from the electronic medical record at the time of the clinic visit. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Miami.

Measurement of Acculturation

An abbreviated 10-item version of the Stephenson Multi-Group Acculturation Scale (SMAS) was used to assess acculturation. Cronbach’s alphas for scores on the abbreviated SMAS were .77 for Hispanic behaviors and .81 for US behaviors. The SMAS was used because it includes separate subscales for Hispanic and US cultural practices—which is consistent with recommendations from leaders in the field of acculturation science [10]. The SMAS was administered by our research coordinators in each participant’s preferred language (English or Spanish). The abbreviated SMAS consists of five items assessing Hispanic behaviors and five items assessing US behaviors. Participants answered each item using a scale ranging from 0 (mostly disagree) to 4 (mostly agree).

We used scale midpoint splits to classify participants into acculturation categories [11]. As per Berry, participants were grouped as bicultural if they scored above a mean response of 2 on both the Hispanic and US scales, primarily Hispanic if they scored higher in the Hispanic domain only (Hispanic mean score ≥ 2, US mean score < 2), and primarily American if they scored higher in the American domain only (US mean score ≥ 2, Hispanic mean score < 2) [10]. Participants scoring below 2 on both the US and Hispanic scales would be classified as marginalized, though this category tends to be extremely small or nonexistent in most immigrant samples [10, 11].

In addition, participants were asked whether they had changed their diet since immigration. This section included the following question: “has your diet changed since immigration to the US and not as a result of illness including gastrointestinal symptoms”; all IBD patients included developed IBD after immigration to the USA.

Dietary Assessment

Dietary intake data were collected and analyzed using the Automated Self-Administered 24-h (ASA-24) Dietary Assessment Tool, version 2014, developed by the National Cancer Institute [13]. This dietary recall is validated in English and Spanish and is designed to allow participants to complete the questionnaires on their own. A bilingual research coordinator provided participants with laptops and provided instructions for completing the ASA-24. A research coordinator was available on site to answer participants’ questions or concerns. Most participants completed all of the questionnaires, including the dietary recall, in one sitting. Patients who did not complete the dietary recall on the day of their clinic visit were asked to provide a date and time to complete the questionnaire by telephone. Four patients were called for follow-up, whereas the remainder completed all measures in a single sitting.

This dietary assessment uses a modified version of the USDA’s Automated Multiple-Pass Method [14]. A total of 67 nutrients and 37 food groups are included in the analysis reports of the ASA-24 recall. Participants provide data on nutrients such as protein, fat, carbohydrates, vitamins, minerals, and fatty acids and on individual food items such as beans and peas, cheese, and pork. Dietary components measured included total daily energy intake (in kilocalories), macronutrients, and micronutrients. Macro- and micronutrients were adjusted for total energy intake.

Diet Quality Assessment

Dietary quality was derived using a validated score, the Healthy Eating Index [15]. Diet quality served as our primary index of nutritional assessment because it allows for categorization of diets according to the extent to which they conform to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans [12]. A HEI-2010 score for each participant was calculated using DHQ II Diet*Calc output using the SAS program. The HEI includes twelve components: total fruit, whole fruit, total vegetables, greens and beans, whole grains, dairy, total protein foods, seafood and plant proteins, fatty acids, refined grains, sodium, and empty calories. The index is used to assess adherence to dietary guidelines released in 2010 [16]. The food group standards are based on the recommendations from MyPyramid [17] and are expressed as a percent of kilojoules (kJ) or per 4184 kJ (or 1000 calories). The HEI is a continuous measure, with 100 being the highest possible composite score for the 12 components and reflecting the best dietary quality (Table 4) [15]. We classified the HEI scores into tertiles, such that a score greater than 80 implicates a “good” eating pattern, a score between 51 and 80 “needs improvement,” and a score of less than 51 represents a “poor” diet. A high score in each individual question indicates greater adherence to dietary recommendations (Table 4).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). SAS version 9.3 was used to calculate Healthy Eating Index scores. We used Chi-square and independent-samples t-tests to compare demographic variables between IBD participants and controls. Independent-samples t-tests were used to compare acculturation scores between IBD participants and controls. Categorical acculturation variables (bicultural, Hispanic, American, and marginalized) were analyzed using Chi-square tests.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of Hispanic IBD Patients and Controls

Several demographic factors were compared between IBD patients and controls. Demographic variables, including age at time of interview, gender, marital status, country of birth, and age at immigration, were not significantly different between IBD patients and controls (Table 1). IBD patients had lived in the USA for an average of 25.5 years (SD 13.5), and healthy controls had lived in the USA for an average of 31.7 years (SD 18.3). Significantly more controls than IBD patients had at least a college education (93.1 vs. 62.1%, χ2 (1, N = 58) = 8.03, p < .01). On average, both IBD patients and controls were overweight, BMI M = 27.2, SD 4.6 and M = 25.7, SD 4.8, respectively, t(55) = .15, d = .30, p = .26).

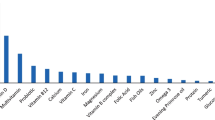

IBD patients and controls had immigrated from nine different Latin American countries (see Fig. 1). Nearly half (41.4%) of IBD patients were born in Cuba, followed by Colombia (13.8%), and Puerto Rico (13.8%). A similar distribution of countries of origin was observed among controls (57.1% Cubans and 28.6% Colombians).

IBD Phenotype in IBD Participants

Within the IBD group, 12 patients had Crohn’s disease and 17 patients had ulcerative colitis. The majority of patients with Crohn’s disease had ileocolonic disease (66.7%) followed by ileal disease (33.3%). About half of ulcerative colitis patients had pancolitis (52.9%); see Table 2. No prior surgeries were recorded in either UC or CD patients. A similar number of patients with UC and CD were on biologics (anti-TNFs or anti-integrins) (see Table 2). No patients were on oral prednisone (Table 2). All IBD patients had mild disease activity (17 UC patients with mean average Mayo endoscopic score of 1.38 and 12 Crohn’s disease patients with average SES-CD score of 5) with all patients having available endoscopy for grading of inflammation.

Changes in Diet Occurring After Immigration

Most patients and controls reported changing their diet after immigration (Table 3). However, a greater proportion of IBD patients (72.4%) reported changing their diet following immigration compared to controls (57.1%), but this proportional difference did not achieve statistical significance (χ2 (1, N = 57) = 1.46, p = .23). IBD patients who reported changing their diet after immigration indicated that they did not have active GI symptoms at the time of immigration.

Diet Quality in IBD Cases and Controls

HEI indexes the participant’s diet in terms of adherence to Federal dietary guidance. The total mean HEI score was similar between IBD patients and controls and was within the “needs improvement” range (M = 53.8, SD 13.9 and M = 56.5, SD 10.5, respectively, t(55) = − .81, p = .42, d = .22. No patients in our study received a total HEI score greater than 80, which is considered an optimal diet. When examining individual HEI food items, we found that IBD patients reported lower intake across all items, particularly total fruit, whole fruit, and total dairy, compared to controls. It is important to note that high HEI scores for sodium, refined grain, and empty calories indicate lower consumption of these food items and therefore adherence to recommended intake. In these food groups, there was a trend for IBD patients to report higher than recommended intake of sodium reflected in lower mean scores (M = 2.0 SD 2.6 in IBD and M = 3.5, SD 3.1 in controls, t(55) = − 1.9, p = .06, d = .52). Similarly, a higher intake of refined grains, and therefore lower mean scores, was observed in IBD patients (M = 5.5, SD 3.8 in IBD and M = 7.6, SD 3.3, t(55) = − 2.2, p = .03, d = .59) compared to controls. However, IBD patients scored more favorably in recommended consumption of empty calories, i.e., they consumed less of these food items (alcohol, solid fats, and added sugars), (M = 17.5, SD 3.9 in IBD compared to M = 13.2, SD 5.2 in controls, t(55) = 3.56, p < .01, d = .93). Both IBD cases and controls reported lower than recommended consumption of total vegetables, legumes, whole grains, and sea plant protein (Table 4).

Acculturation in IBD Patients Compared to Controls

Global Acculturation

When categorizing our patients into bicultural, American, Hispanic, or marginalized, the majority of our patients were classified as bicultural: 17 (58.6%) of IBD participants compared to 21 (72.4%) of controls, χ2 (3, N = 58) = 3.31, p = .35 (Table 3). Individual items examining social and language components for US and Hispanic acculturation did not differ between IBD participants and controls (Table 3). IBD participants and controls scored similarly on Hispanic cultural behaviors (M = 3.39, SD 0.7 in IBD participants versus M = 3.26, SD 0.7 in controls; t(56) = − .65, p = .52, d = .17); we also observed patterns for US cultural behaviors (M = 2.15, SD 0.9 in IBD participants and M = 2.5, SD 1.1 in controls, t(56) = − 1.2, p = .21, d = .33).

IBD patients scored higher on the SMAS dietary American acculturation items, but this difference was not statistically significant (Table 3). The dietary items referred to knowing how to prepare American foods (M = 2.86 SD 1.48 in IBD participants versus M = 2.76, SD 1.50 in controls, t(56) = − .53, p = .59, d = .067) and eating American foods (M = 2.69, SD 1.17 in IBD versus M = 2.76, SD 1.35 in controls, t(56) = − .21, p = .84, d =.05). Similarly, controls scored higher than IBD patients on the dietary Hispanic item, but this difference was not statistically significant (M = 3.48 SD .87 in controls compared to M = 3.31 SD 1.17 in IBD patients, t(56) = − .64, p = .53, d = .16).

Discussion

This is the first study to examine acculturation and diet among Hispanic immigrant patients living with IBD in the USA. It is essential to identify influential dietary and cultural practices that could explain the rising incidence of IBD in US immigrant and minority groups. We found no differences in US acculturation, including dietary acculturation, between Hispanics with and without IBD. In fact, both IBD and control participants were mostly bicultural, likely as a result of extended US residence (mean years in the USA was 28.6). In this study, we found that most Hispanics changed their diet following US immigration, with IBD patients most likely to report changes (72% vs. 57%). Additionally, we found similar poor eating behaviors, as measured using the Healthy Eating Index, in both IBD patients and controls. Given our findings, we conclude that dietary changes and adoption of US behaviors, on their own, do not explain the rise in IBD among Hispanic immigrants.

More than half of all participants, including both IBD patients and controls, reported changing their diet after immigration and not as a result of new diseases or financial constraints. A greater percentage of the IBD patients changed their diet and stated that they did so prior to developing any illness, although this difference did not reach statistical significance. This finding supports the notion that Western dietary acculturation on its own may not fully explain the rise of IBD among Hispanics. We have recently examined the genetic underpinnings of IBD in Hispanics and found that their genetic load is similar to non-Hispanic whites, suggesting that differences in incidence of IBD also do not rest in genetics alone [18]. Future studies need to investigate the interaction of diet with IBD genetic predisposition, as well as with microbiome interactions, that could better close in on the pathologic underpinnings of IBD in Hispanics.

Most Hispanics in our study, including IBD and controls, were classified as bicultural. The two groups reported similar levels of liking and knowing how to prepare American foods. We also observed similar levels in Hispanic dietary preferences and in other US and Hispanic cultural behaviors across groups, including language and social components. Therefore, these findings indicate that Hispanic immigrants with IBD and their non IBD counterparts share similar cultural dietary preferences that suggest a blend of Hispanic and American practices. Although we did not find that US and Hispanic dietary preferences differed between IBD and controls in Hispanics, we did find that, in general, Hispanic immigrants adopt American practices, which have been associated with development of various diseases in prior studies [18,19,20]. For instance, in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), Mexicans were more likely to adhere to dietary guidelines if they were born in Mexico than in the USA [19]. Recent reviews also indicate that Hispanic immigrants arrive in the USA practicing healthier behaviors than White Americans—but as they adopt American behaviors, they experience a high burden of poor health outcomes such as type 2 diabetes [19, 20]. Evidence is also mounting that second-generation Hispanics’ diets are less healthy compared to those of foreign-born Hispanics—such that second-generation Hispanics live approximately 2.9 years less than Hispanic immigrants [21].

In our study, we found that both IBD and controls scored within the “needs improvement” range in their overall HEI diet assessment and are not in adherence to recommended dietary guidelines. Interestingly, both groups scored below recommended standards but for differing reasons. IBD patients had lower than recommended intake across several food groups, including vegetable and fruit intake, perhaps as a result of GI symptoms brought on with food items high in fiber. In turn, IBD patients replaced high-fiber foods with foods high in salt and refined grains. Control participants ate less than optimally because of lower adherence to recommended intake of vegetables, sea, and plant protein, as well as greater consumption of “empty calories,” which included greater intake of alcohol and of foods with added sugars and solid fats. The dietary patterns among controls may be explained by greater adherence to an “American diet” characterized by higher intake of fats and added sugars, coupled with low intake of fruits and vegetables. The patterns among control participants are likely a result of symptom-based elimination diets. In a prior survey study, 71% of IBD patients believe their diet affects their symptoms [22], and as high as 90% of Crohn’s disease patients utilize elimination diets to minimize their symptoms [23]. Unfortunately, dietary modification based solely on symptom control can lead to avoiding nutritionally important foods and increased risk for nutritional deficiencies [24]. Our results highlight the importance of emphasizing healthy dietary practices among IBD patients, which can in turn also influence the course of ongoing disease progression [25].

The present findings should be interpreted in light of some important limitations. Although we conducted a cross-sectional study evaluating current dietary intake, our sample size was small. However, our study is a first-pass examination, and our findings suggest some clinically significant differences in diet quality. Our IBD patients and controls were similar in terms of proportions of countries represented, age at immigration, and gender—all factors that can influence diet and acculturation. Therefore, differences observed between IBD patients and controls were not likely a result of differences in these variables. Additionally, nutritional intake may be influenced by disease activity in our IBD patients. IBD patients may choose to avoid “trigger” foods that can worsen their symptoms and so this may alter their daily consumption [24]. To minimize the chances that diet intake was influenced by current disease activity, we chose IBD patients without a prior surgical history, and who reported minimal active GI symptoms or a change in diet in the last week.

Our results underscore the importance of cultural behaviors and highlights how behaviors and cultural beliefs can change as a result of immigration and duration in the US. Findings also indicate that most Hispanics change their diet upon arrival to the USA and that their diet is poor regardless of disease status. Further studies are needed to validate these findings and to identify the role that diet plays when in the presence of other risk factors, including IBD genetic predisposition. We hope that the present work inspires additional research examining links between acculturation and diet among individuals with various health conditions.

References

Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1424–1429.

Kamm MA. Rapid changes in epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet. 2018;390:2741–2742.

Benchimol EI, Mack DR, Guttmann A, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in immigrants to Canada and their children: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:553–563.

Hou JK, El-Serag H, Thirumurthi S. Distribution and manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease in Asians, Hispanics, and African Americans: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2100–2109.

Damas OM, Avalos DJ, Palacio AM, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease is presenting sooner after immigration in more recent US immigrants from Cuba. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:303–309.

Avalos DJ, Mendoza-Ladd A, Zuckerman MJ, et al. Hispanic Americans and Non-Hispanic White Americans have a similar inflammatory bowel disease phenotype: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-018-5022-7.

Damas OM, Jahann DA, Reznik R, et al. Phenotypic manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease differ between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites: results of a large cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:231–239.

Effoe VS, Chen H, Moran A, et al. Acculturation is associated with left ventricular mass in a multiethnic sample: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015;15:161.

Vaeth PA, Willett DL. Level of acculturation and hypertension among Dallas County Hispanics: findings from the Dallas Heart Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15:373–380.

Berry JW. Theories and models of acculturation. In: Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, eds. Oxford Handbook of Acculturation and Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2017:15–28.

Coatsworth JD, Maldonado-Molina M, Pantin H, et al. A person-centered and ecological investigation of acculturation strategies in Hispanic immigrant youth. J Community Psychol. 2005;33:157–174.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 2015. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/. Accessed December 20, 2017.

Institute NC. Automated self-administered 24-hour (ASA24®) dietary assessment tool; 2009. https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/asa24/2014. Accessed June 17, 2017.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. AMPM - USDA Automated Multiple-Pass Method; 2016. https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/ampm-usda-automated-multiple-pass-method/. Accessed August 16, 2017.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. Healthy Eating Index (HEI); 2010. https://www.cnpp.usda.gov/healthyeatingindex. Accessed December 20, 2017.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture 2010 Dietary Guidelines; 2010. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2010/. Accessed December 20, 2017.

USDA. Food Guide Pyramid. 1992. https://www.cnpp.usda.gov/fgp. Accessed December 20, 2017.

Damas OM, Gomez L, Quintero MA, et al. Genetic characterization and influence on inflammatory bowel disease expression in a diverse Hispanic South Florida Cohort. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2017;8:e87.

Perez-Escamilla R. Acculturation, nutrition, and health disparities in Latinos. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:1163S–1167S.

Pérez-Escamilla R. Health care access among Latinos: implications for social and health care reforms. J Hispanic High Educ. 2010;9:43–60.

Tavernise S. The Health Toll of Immigration. The New York Times; 2013.

Holt DQ, Strauss BJ, Moore GT. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease and their treating clinicians have different views regarding diet. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2017;30:66–72.

Owczarek D, Rodacki T, Domagala-Rodacka R, et al. Diet and nutritional factors in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:895–905.

Casanova MJ, Chaparro M, Molina B, et al. Prevalence of malnutrition and nutritional characteristics of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:1430–1439.

Suskind DL, Cohen SA, Brittnacher MJ, et al. Clinical and fecal microbial changes with diet therapy in active inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;52:155–163.

Funding

The study was funded by Broad grant, Arison Foundation, NIH Grant R01-DK104844.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at the University of Miami.

Informed consent

Informed consent was attained from each participant in this study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Damas, O.M., Estes, D., Avalos, D. et al. Hispanics Coming to the US Adopt US Cultural Behaviors and Eat Less Healthy: Implications for Development of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig Dis Sci 63, 3058–3066 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-018-5185-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-018-5185-2