Abstract

Background

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a devastating immune-mediated disease on the rise in Hispanics living in the USA. Prior observational studies comparing IBD characteristics between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites (NHW) have yielded mixed results.

Aims

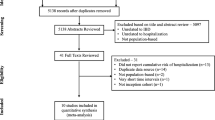

We performed a meta-analysis of observational studies examining IBD phenotype in Hispanics compared to NHW.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of US-based studies comparing IBD subtype (Ulcerative Colitis: UC or Crohn’s disease: CD) and phenotype (disease location and behavior) between Hispanics and NHW. We evaluated differences in age at IBD diagnosis, the presence of family history and smoking history. A random effects model was chosen “a priori.” Categorical and continuous variables were analyzed using odds ratio (OR) or standard mean difference (SMD), respectively.

Results

Seven studies were included with 687 Hispanics and 1586 NHW. UC was more common in Hispanics compared to NHW (OR 2.07, CI 1.13–3.79, p = 0.02). Location of disease was similar between Hispanics and NHW except for the presence of upper gastrointestinal CD, which was less common in Hispanics (OR 0.58, CI 0.32–1.06, p = 0.07). Hispanics were less likely to smoke (OR 0.48, CI 0.26–0.89, p = 0.02) or have a family history of IBD (OR 0.35, CI 0.22–0.55, p < 0.001). CD behavior classified by Montreal classification and age at IBD diagnosis were similar between Hispanics and NHW.

Conclusion

UC was more common among US Hispanics compared to NHW. Age at IBD diagnosis is similar for both Hispanics and NHW. For CD, disease behavior is similar, but Hispanics show a trend for less upper gastrointestinal involvement. A family history of IBD and smoking history were less common in Hispanics.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Understanding and preventing the global increase of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(313–321):e312.

Ng SC, Bernstein CN, Vatn MH, et al. Geographical variability and environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2013;62:630–649.

Dahlhamer JM, Zammitti EP, Ward BW, et al. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease among adults aged >/=18 years—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1166–1169.

Bosques-Padilla FJ, Sandoval-Garcia ER, Martinez-Vazquez MA, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of ulcerative colitis in north-eastern Mexico. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2011;76:34–38.

Farrukh A, Mayberry JF. Inflammatory bowel disease in Hispanic communities: a concerted South American approach could identify the aetiology of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Arq Gastroenterol. 2014;51:271–275.

Mendoza Ladd A, Jia Y, Yu C, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of a predominantly hispanic population with inflammatory bowel disease on the US-Mexico border. South Med J.. 2016;109:792–797.

Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, et al. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011458.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012.

Basu D, Lopez I, Kulkarni A, et al. Impact of race and ethnicity on inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2254–2261.

Damas OM, Jahann DA, Reznik R, et al. Phenotypic manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease differ between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites: results of a large cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:231–239.

Hou J, El-Serag H, Sellin J, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease characteristics and treatment in Hispanics and Caucasians. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1476–1481.

Mannino C, Malin J, Conn AR, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in inflammatory bowel disease phenotypes at a tertiary care academic medical center. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:S389.

Nguyen GC, Torres EA, Regueiro M, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease characteristics among African Americans, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic Whites: characterization of a large North American cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1012–1023.

Sewell JL, Inadomi JM, Yee HF Jr. Race and inflammatory bowel disease in an urban healthcare system. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3479–3487.

Betteridge JD, Armbruster SP, Maydonovitch C, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease prevalence by age, gender, race, and geographic location in the U.S. military health care population. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1421–1427.

Nguyen GC, Chong CA, Chong RY. National estimates of the burden of inflammatory bowel disease among racial and ethnic groups in the United States. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:288–295.

Kim HJ, Hann HJ, Hong SN, et al. Incidence and natural course of inflammatory bowel disease in Korea, 2006–2012: a nationwide population-based study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:623–630.

Ng SC, Tang W, Ching JY, et al. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-pacific Crohn’s and colitis epidemiology study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(158–165):e152.

Wei SC, Lin MH, Tung CC, et al. A nationwide population-based study of the inflammatory bowel diseases between 1998 and 2008 in Taiwan. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:166.

Juliao F, Marquez J, Aristizabal N, et al. Clinical efficacy of infliximab in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis in a latin american referral population. Digestion. 2013;88:222–228.

Paredes Mendez J, Moreno Otoya, Mestanza Rivas Plata AL, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease in a tertiary referral hospital in Lima-Peru. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2016;36:209–218.

Simian D, Fluxa D, Flores L, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease: a descriptive study of 716 local Chilean patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:5267–5275.

Yamamoto-Furusho JK. Clinical epidemiology of ulcerative colitis in Mexico: a single hospital-based study in a 20-year period (1987–2006). J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:221–224.

Torres EA, Cruz A, Monagas M, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in Hispanics: The University of Puerto Rico IBD registry. Int J Inflamm. 2012;2012:574079.

Baños FJ, Ruiz Vélez MH, Flórez Arango JF. Phenotypes and natural history of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) in a referral population in Medellín, Colombia. Revista Colombiana de Gastroenterología. 2010;25:240–251.

Damas OM, Avalos DJ, Palacio AM, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease is presenting sooner after immigration in more recent US immigrants from Cuba. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:303–309.

Shivashankar R, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, et al. Incidence and prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota from 1970 through 2010. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:857–863.

Parente JM, Coy CS, Campelo V, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in an underdeveloped region of Northeastern Brazil. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1197–1206.

Garcia-Subirats I, Vargas I, Mogollon-Perez AS, et al. Inequities in access to health care in different health systems: a study in municipalities of central Colombia and north-eastern Brazil. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13:10.

Bureau UC. Americans Are Visiting the doctor less frequently, Census Bureau Reports. 2012. Available at: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/health_care_insurance/cb12-185.html Accessed 25.10.17.

Vazquez ML, Vargas I, Garcia-Subirats I, et al. Doctors’ experience of coordination across care levels and associated factors. A cross-sectional study in public healthcare networks of six Latin American countries. Soc Sci Med. 2017;182:10–19.

Morgan BW, Leifheit KM, Romero KM, et al. Low cigarette smoking prevalence in peri-urban Peru: results from a population-based study of tobacco use by self-report and urine cotinine. Tob Induc Dis. 2017;15:32.

Weygandt PL, Vidal-Cardenas E, Gilman RH, et al. Epidemiology of tobacco use and dependence in adults in a poor peri-urban community in Lima, Peru. BMC Pulm Med. 2012;12:9.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PloS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Avalos, D.J., Mendoza-Ladd, A., Zuckerman, M.J. et al. Hispanic Americans and Non-Hispanic White Americans Have a Similar Inflammatory Bowel Disease Phenotype: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Dig Dis Sci 63, 1558–1571 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-018-5022-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-018-5022-7