Abstract

Background

Proton pump inhibitors are commonly used to treat gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) and nonerosive GERD (NERD) in adolescents and adults. Despite the efficacy of available medications, many patients have persisting symptoms, indicating a need for more effective agents.

Aims

To assess the safety and efficacy of dexlansoprazole dual delayed-release capsules in adolescents for treatment of symptomatic NERD.

Methods

A phase 2, open-label, multicenter study was conducted in adolescents aged 12–17 years. After a 21-day screening period, adolescents with endoscopically confirmed NERD received a daily dose of 30-mg dexlansoprazole for 4 weeks. The primary endpoint was treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) experienced by ≥5% of patients. The secondary endpoint was the percentage of days with neither daytime nor nighttime heartburn. Heartburn symptoms and severity were recorded daily in patient electronic diaries and independently assessed by the investigator, along with patient-reported quality of life, at the beginning and end of the study.

Results

Diarrhea and headache were the only TEAEs reported by ≥5% of patients. Dexlansoprazole-treated patients (N = 104) reported a median 47.3% of days with neither daytime nor nighttime heartburn. Symptoms such as epigastric pain, acid regurgitation, and heartburn improved in severity for 73–80% of patients. Pediatric Gastroesophageal Symptom and Quality of Life Questionnaire-Adolescents-Short Form symptom and impact subscale scores (scaled 1–5) each decreased by an average of 0.7 units at week 4.

Conclusions

Use of 30-mg dexlansoprazole in adolescent NERD was generally well tolerated and had beneficial effects on improving heartburn symptoms and quality of life.

Trial Registration

This study has the ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01642602.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a disorder involving troublesome symptoms associated with persistent reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus [1]. Symptoms include heartburn, cough, epigastric pain, vomiting, and regurgitation. These symptoms affect 18–28% of North American adults, according to a recent systematic review of 4 studies that collectively surveyed over 9000 patients [2,3,4,5,6]. GERD is proposed to have 5 distinct presentations—nonerosive GERD (NERD), erosive esophagitis (EE), functional heartburn, hypersensitive esophagus, and Barrett’s esophagus. Despite the similarity of symptoms among the GERD phenotypes, they are clinically distinct rather than continuous [7]. NERD and EE are common GERD phenotypes, with occurrence rates of up to 83% in some European populations for NERD [11, 12] and global region-dependent EE rates ranging from 3 to 18% for EE [13]. EE is characterized by esophageal mucosal breaks detected by endoscopy, while lack of damage to the esophageal mucosa in the presence of GERD symptoms suggests a NERD diagnosis [8,9,10].

The prevalence of GERD symptoms has risen from 11.6% in 1995–1997 to 17.1% in 2006–2009 [14], and awareness of GERD has concomitantly increased in pediatric and adolescent populations [15, 16]. Two large studies in pediatric patients have reported that 18% experience weekly heartburn and 20% experience GERD symptoms [4, 9, 17]. In addition, an analysis of 1.2 million insurance claims found that incidence rate of GERD in patients aged 12–17 years increased by 34% from 2000 to 2005 [18]. GERD may also have a relation to other diseases affecting adolescents, although further investigation is required [1, 19, 20]. Asthma was positively correlated with GERD symptoms in adolescents (13–16 years), and the correlation was greater in individuals with more recent asthma attacks [17]. Comorbid complicated GERD can occur with other conditions such as neurological impairment, hiatal hernia, and bronchopulmonary dysplasia [21]. An increased risk of GERD is also linked with childhood obesity [22]. Persistence of adolescent symptoms of GERD may be related to the presence of GERD in adults [23,24,25].

Typically, management of GERD has included lifestyle changes (for example, diet, weight loss, or sleeping position), over-the-counter antacids, histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs), and more recently, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). While H2RAs block the histamine receptors that modulate gastric acid secretion overall, PPIs block acid production directly in the parietal cells of the stomach [1]. PPIs are considered superior to H2RAs for healing of EE and relief of GERD symptoms and have become the pharmacological mainstay for treatment of adult and adolescent GERD [1, 15]. Commercially available FDA-approved PPIs, such as esomeprazole, pantoprazole, lansoprazole, and rabeprazole, have demonstrated efficacy in treating GERD; however, there is still a need for additional treatment options in adolescents [26,27,28,29,30]. For example, in a study of 8-week lansoprazole in adolescent patients with NERD, 38% of patients still had partial or unresolved symptoms [31].

Dexlansoprazole, an enantiomer of lansoprazole, was approved for healing of EE at a 60-mg dose and at a 30-mg dose for treatment of symptomatic NERD and maintenance of healed EE and relief of heartburn for up to 6 months in adults and pediatric patients 12–17 years old [32]. The pharmacokinetic profile of 30- and 60-mg dexlansoprazole capsules QD in adolescents has been established and is similar to that of adults [32, 33]. Here, we present the safety and efficacy of dexlansoprazole for heartburn relief in adolescents with NERD.

Methods

Study Design

This was an international phase 2, open-label, multicenter, 4-week study to assess the safety and efficacy of 30-mg dexlansoprazole QD for relief of heartburn in adolescents with symptomatic NERD (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01642602) [34]. The study, conducted from June 22, 2012 to January 14, 2014, screened adolescents across 71 sites in North America, Latin America, and Europe and was conducted according to the principles described in the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonization Harmonized Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice [35, 36]. Patient assent and parent/guardian consent were obtained prior to study procedures.

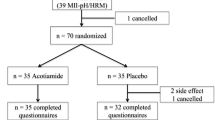

A schematic of the study design is outlined in Fig. 1. The study comprised a screening period of up to 21 days before study start, followed by a 4-week treatment phase, and a post-treatment telephone follow up 5–10 days after the last dose of study drug. Dexlansoprazole was self-administered (under parental/guardian oversight, if necessary) as a 30-mg capsule QD regardless of food intake from day 1.

Study design. The study was composed of three periods: The screening period, during which a patient had to display heartburn symptoms for 3 days out of any 7 consecutive days; a 4-week treatment period; and a follow-up period of 5–10 days. Diary entries and treatment compliance were reviewed at enrolment, week 2, and week 4 or final visit, as well as on any unscheduled visits. A final phone call was conducted to record any new adverse events during the follow-up period. eDiary electronic diary, NERD nonerosive gastro-esophageal reflux disease, QD once daily

Evaluations during the screening period included medical and social history, physical examination, endoscopy, esophageal and gastric biopsies, and concomitant medication assessment. Patients recorded their symptoms in electronic diaries (eDiaries) and these included the presence and degree of heartburn symptom pain every morning upon waking and every evening at bedtime during the screening and treatment periods (Supplementary Table S1). Rescue medications (magnesium or aluminum-based antacids) were available for the entire screening and treatment period, and their use was recorded in the eDiary. Medication and eDiary compliance and adverse events (AEs) were assessed at scheduled clinic visits on day −1 and week 4/final visit, by a phone call at week 2, and on any unscheduled visits (Fig. 1). Quality of life was assessed from the patient at baseline and at week 4/final visit using the Pediatric Gastro-esophageal Symptom and Quality of Life Questionnaire-Adolescent-Short Form (PGSQ-A-SF) [37].

Patients

Patients aged 12–17 years of either sex were eligible for the study if they had a medical history of GERD symptoms for at least 3 months before screening, documented in their eDiaries the presence of heartburn (a burning feeling in the mid-epigastric area and/or chest area) for at least 3 of any 7 consecutive days during the study period (consistent with the Montreal definition and classification of GERD for adults) [38, 39], and a lack of esophageal damage confirmed by endoscopy before day −1. All sexually active participants agreed to use contraception during the study and for 30 days after the last dose of study medication.

Patients were excluded from the study if they had any of the following: coexisting esophageal disease confirmed by endoscopy, including eosinophilic esophagitis and Barrett’s disease; other gastrointestinal conditions, such as Zollinger–Ellison syndrome, gastric or duodenal ulcers, or celiac disease; PPI use within 7 days of screening; a need to take or anticipated need to take an excluded concomitant medication (for example, H2RAs, corticosteroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, anticholinergics, or prokinetics) during the study evaluation period; hypersensitivity or allergies to any PPI, dexlansoprazole, or any component of dexlansoprazole; inpatient surgery scheduled to occur during the study.

Patients could discontinue the study after voluntary withdrawal or because of an AE, protocol deviation, or lack of follow-up. These patients were not replaced.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was to determine the treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) experienced by ≥5% of patients. TEAEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA; version 16.1 International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations, Geneva, Switzerland) [40]. Intensity of the AEs was defined as “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe.” “Mild” referred to an event that was transient and easily tolerated. AEs were considered “moderate” if they caused discomfort and interruption of the usual activities. “Severe” AEs were defined as those causing considerable interference with the patient’s usual activities.

The secondary endpoint was the percentage of days without daytime and nighttime heartburn during the treatment period, as assessed by eDiary (Supplementary Table S1). Additional endpoints included:

-

Mean degree to which daytime and nighttime heartburn was painful (recorded in the eDiary using the following scales: 0 = report of no heartburn; 1 = did not hurt very much; 2 = hurt some; and 3 = hurt a lot).

-

Percentage of days without daytime heartburn over the treatment period.

-

Percentage of days without nighttime heartburn over the treatment period.

-

Investigator assessment of NERD symptom severity (defined in Supplementary Table S2).

-

Change from baseline to week 4 in PGSQ-A-SF symptom and impact subscale scores.

-

Percentage of days without rescue medication use during the treatment period.

Analytical Plan and Statistics

For the safety analysis, all data from patients who received at least 1 dose of study drug were evaluated. For the efficacy analysis, data from patients who received at least 1 dose of study drug and had post-baseline data were evaluated. Summary statistics (means, medians, and standard deviations) were calculated for variables such as age, bodyweight, body mass index (BMI), and disease characteristics (heartburn assessments, patient-reported quality of life scores, rescue medication use). Categorical variables such as concurrent medical conditions and TEAEs were summarized by the number and percentage of the patients in each category. No formal statistical testing was conducted. No formal sample size calculation was performed as this was an open-label safety study.

The percentage of days without daytime or nighttime heartburn was presented for patients with results during the 4-week treatment period up to the last dosing day or until day 35 (whichever occurred earlier). If data from the last dose date was missing, then 35 days was imputed as the length of the treatment period. If both daytime and nighttime heartburn results were missing from the eDiaries, that date was excluded from the percentage of days without daytime or nighttime heartburn. For the PGSQ-A-SF symptom and impact subscale scores, if more than 50% of the item scores were missing, then the subscale score was set to missing for that day. Internal consistency of PGSQ-A-SF symptom and impact subscale scores was assessed by calculating Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

Results

Patients

A total of 104 patients were enrolled and 102 patients completed the study (Fig. 2). The mean compliance rate for dexlansoprazole was 96.6% (standard deviation = 12.7%), with 43.3% of patients taking the medication for 22–28 days and 54.8% taking it for 29 days or more.

Patient disposition. A total of 161 patients were screened for the study, and 57 were not enrolled; the primary reason for screening failure was not meeting the entrance criteria. aNon-compliance with study visits (3), met exclusion criteria (2), eDiary non-compliance (1), subject had irritable bowel syndrome (1), Vicodin use (1). QD once daily

Patient demographics are presented in Table 1. A majority of patients were white (91.3%) and female (70.2%). The population mean BMI was 23 ± 4.4 kg/m2. At baseline, 14% of the population was positive for Helicobacter pylori infection. The most common non-gastrointestinal-related medical conditions were seasonal allergy (13.5%), drug hypersensitivity (11.5%), asthma (9.6%), and headache (9.6%) (Supplementary Table S3).

Safety

Most of the TEAEs reported were mild (79.7%) or moderate (18.8%) (Table 2), and the most common AEs reported were diarrhea (6.7%) and headache (6.7%). Every other AE, including upper abdominal pain, vomiting, bronchitis, nasopharyngitis, influenza, and increased appetite, occurred in 3.8% or less of patients. There were no serious AEs or deaths reported (Table 2).

One patient suffered a severe TEAE (abdominal pain) unrelated to study drug. Two patients discontinued the study because of a TEAE (Fig. 2; Table 2). One was a 16-year-old female patient who experienced refractory NERD on day 15, which continued intermittently for 19 days and was not considered to be study drug related. The other patient who withdrew from the study was a 17-year-old male patient who experienced dizziness that was ongoing from day 10 to study end and was considered to be related to the study drug. Other drug-related AEs included abnormal dreams, dry mouth, and abdominal pain. In total, 5% of patients had TEAEs that were considered to be related to the study drug.

Efficacy

Patient Assessment of Heartburn

Before the study, patients experienced heartburn most of the time, with a median of 6.0 days (mean 5.1) in the 7 days before the start of treatment and a median degree of pain of 1.08 (mean 1.19) on a scale from 0 (no pain) to 3 (hurts a lot) (Table 3). Heartburn was more frequent and more severe during the day than at night, and rescue medication was used for a median of 1 day (Table 3).

During the 4-week treatment period, the occurrence of heartburn was reduced; patients did not experience any heartburn for a median 47.3% (mean 47.1%) of days, and the median degree of pain was 0.49 (mean 0.68). During treatment, improvements were seen in daytime heartburn pain (1.29 during the 7-day baseline period and 0.64 during the 4-week treatment period) as well as nighttime heartburn pain (0.71 during the 7-day baseline period and 0.30 during the 4-week treatment period). During treatment, patients experienced a median of 59.3% heartburn-free days (mean 55.2%) and a median of 80.5% of heartburn-free nights (mean 69.1%); the median and mean percentage of days without rescue medication use during treatment was 83.9 and 70.4%, respectively (Table 4).

Investigator Assessment of GERD Symptoms

According to investigator assessment, heartburn was the most prevalent GERD symptom in this study, with 91.6% of patients having heartburn to some degree at baseline (Table 3). At week 4, 80.4% of these patients had their heartburn improved in severity by at least 1 category from baseline as assessed by the investigator (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table S2). Similar percentages of patients with acid regurgitation (78.1%), dysphagia (76.9%), epigastric pain (76.0%), and belching (72.6%) had their symptoms improved over the course of treatment (Fig. 3).

Patient-Reported Quality of Life

Median baseline PGSQ-A-SF symptom and impact subscale scores were 2.4 and 2.8 (mean 2.5 and 2.6), respectively (Table 3). Both scores decreased by an average of 0.7 units each at week 4, indicating an overall decrease in symptoms and an improvement in quality of life (Fig. 4a, b). Scores for all 7 of the individual items comprising the symptom subscale decreased from baseline, with the largest mean decrease observed in epigastric pain and the smallest mean decrease noted with a vomit taste in mouth (Fig. 4a). Similarly, scores for all 4 of the individual items comprising the impact subscale decreased from baseline, with the largest mean decrease noted in the food restrictions category and smallest mean decrease noted in both liquid restriction and irritability subcategories (Fig. 4b). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the symptom and impact subscales were 0.81 and 0.82, respectively, indicating a high internal consistency (>0.70) for these scores [41, 42].

Patient-reported quality of life. a The PGSQ-A-SF symptom subscale measured the number of days over the past 7 days that patients experienced each individual symptom, where 1 = 0 days; 2 = 1 or 2 days; 3 = 3 or 4 days; 4 = 5 or 6 days; and 5 = every day (7 days). Mean symptom subscale score is the mean of the seven individual symptom item scores. b The PGSQ-A-SF impact subscale measures the impact of symptoms on school, family, and social activities in the past 7 days, where 1 = never; 2 = almost never; 3 = sometimes; 4 = almost always; and 5 = always. Mean impact subscale score is the mean of the four individual impact item scores. PGSQ-A-SF Pediatric Gastro-esophageal Symptom and Quality of Life Questionnaire-Adolescent-Short Form, SD standard deviation

Discussion

PPIs are well-established therapies for both adolescent and adult NERD, in particular, heartburn relief, and are considered more effective than H2RAs [1, 43, 44]. Modified release dexlansoprazole capsules were designed to expand existing PPI treatment options for adolescents by employing a modified release formulation with two different types of granules that have a pH-dependent release profile: the first granule type is released within 1–2 h of administration and is followed by release of the second granule type within 4–5 h [45]. This allows prolonged drug exposure and an extended duration of acid suppression with once daily dosing [45, 46]. In addition, dexlansoprazole does not have food restrictions, whereas other commercially available FDA-approved PPIs are taken 30 min before the first meal of the day.

Dexlansoprazole 30 mg QD was well tolerated in adolescent patients with NERD, consistent with reported studies in adults [47]. Almost all patients completed the 4-week study with only two patients discontinuing treatment because of a TEAE. The majority of TEAEs were classified as mild, with the most frequently reported being diarrhea and headache (6.7% each), similar to adult NERD study [47].

The efficacy measures collected here further demonstrate that dexlansoprazole treatment can benefit adolescent NERD patients in managing daytime and nighttime heartburn. During the 4-week treatment period, the median degree of heartburn pain was 0.64 during the day and 0.30 at night. On a scale of 0–3, these values suggest that with treatment, at least 50% of patients had either no heartburn or heartburn that was not very painful. Patient-reported PGSQ-A-SF scores similarly suggest that dexlansoprazole can improve the quality of life of adolescents with NERD. Dexlansoprazole reduced the frequency of additional reflux-related symptoms including throat irritation, dyspepsia, nausea, and epigastric pain experienced by adolescent patients, as well as reduced the subjective impact of these symptoms on the patient’s eating habits, fatigue, and mood.

This study was limited in that it was an open-label study of small sample size, precluding extrapolation to a broader adolescent NERD population. However, these results are consistent with those from earlier studies showing the benefit of dexlansoprazole for the treatment of NERD in adults. This study reported median percentages of 59.3% for those without daytime heartburn and 80.5% for those without nighttime heartburn. These results are similar to those of a previous study of 947 adult NERD patients treated with dexlansoprazole 30 mg QD, which reported median percentages of 24-h heartburn-free days of 54.9% and heartburn-free nights of 80.8% [47].

Overall, GERD symptoms are observed with similar occurrence rates, ranging from 25 to 40%, in adolescents and adults [15, 24, 48]. Recent reports have indicated that the prevalence of GERD in adolescents is increasing, and the persistence of symptoms suggested a need for additional treatment options in this patient population [15, 18]. Considering the high occurrence in both populations, focus should be given in treating adolescents, as the disease has been reported to persist into adulthood [24, 25]. However, disease progression is less defined and still open to interpretation, pending more research [11, 49].

In conclusion, this study shows that dexlansoprazole is safe and effective for the treatment of adolescent NERD, in particular, relief of heartburn symptoms. Though the sample size is limited, there is a clear similarity with the efficacy and safety results as previously reported in adult population.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

-

Table S1. Electronic diary. Contains questions and response choices.

-

Table S2. Definitions and severities of GERD symptoms as assessed by the investigator.

-

Table S3. Concurrent medical conditions at baseline.

References

Vandenplas Y, Rudolph CD, Di Lorenzo C, et al. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: joint recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:498–547.

El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, Dent J. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2014;63:871–880.

Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Schleck CD, Melton LJ III. Dyspepsia and dyspepsia subgroups: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1259–1268.

Locke GR III, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ III. Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448–1456.

Locke GR III, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ III. Risk factors associated with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Med. 1999;106:642–649.

El-Serag HB, Petersen NJ, Carter J, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux among different racial groups in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1692–1699.

Nwokediuko SC. Current trends in the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a review. ISRN Gastroenterol. 2012;2012:391631.

Sugimoto M, Nishino M, Kodaira C, et al. Characteristics of non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease refractory to proton pump inhibitor therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1858–1865.

Guimaraes EV, Guerra PV, Penna FJ. Management of gastroesophageal reflux disease and erosive esophagitis in pediatric patients: focus on delayed-release esomeprazole. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2010;6:531–537.

Gupta SK, Hassall E, Chiu YL, Amer F, Heyman MB. Presenting symptoms of nonerosive and erosive esophagitis in pediatric patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:858–863. doi:10.1007/s10620-006-9095-3.

Hershcovici T, Fass R. Nonerosive reflux disease (NERD)—an update. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;16:8–21.

Jones R. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in general practice. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1995;211:35–38.

Seo GS, Jeon BJ, Chung JS, et al. The prevalence of erosive esophagitis is not significantly increased in a healthy Korean population—could it be explained? A multi-center prospective study. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19:70–77.

Ness-Jensen E, Lindam A, Lagergren J, Hveem K. Changes in prevalence, incidence and spontaneous loss of gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: a prospective population-based cohort study, the HUNT study. Gut. 2012;61:1390–1397.

Gold BD, Freston JW. Gastroesophageal reflux in children: pathogenesis, prevalence, diagnosis, and role of proton pump inhibitors in treatment. Paediatr Drugs. 2002;4:673–685.

Nelson SP, Chen EH, Syniar GM, Christoffel KK. Prevalence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux during childhood: a pediatric practice-based survey. Pediatric Practice Research Group. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:150–154.

Chen JH, Wang HY, Lin HH, Wang CC, Wang LY. Prevalence and determinants of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in adolescents. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:269–275.

Nelson SP, Kothari S, Wu EQ, Beaulieu N, McHale JM, Dabbous OH. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux disease and acid-related conditions: trends in incidence of diagnosis and acid suppression therapy. J Med Econ. 2009;12:348–355.

Siegel PD, Katz J. Respiratory complications of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Prim Care. 1996;23:433–441.

Gunasekaran TS, Dahlberg M. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in adolescents: is there a difference in different racial and ethnic groups? Dis Esophagus. 2011;24:18–24.

Jung AD. Gastroesophageal reflux in infants and children. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1853–1860.

Koebnick C, Getahun D, Smith N, Porter AH, Der-Sarkissian JK, Jacobsen SJ. Extreme childhood obesity is associated with increased risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease in a large population-based study. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6:e257–e263.

Waring JP, Feiler MJ, Hunter JG, Smith CD, Gold BD. Childhood gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in adult patients. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35:334–338.

Gremse DA. GERD in the pediatric patient: management considerations. MedGenMed. 2004;6:13.

El-Serag HB, Gilger M, Carter J, Genta RM, Rabeneck L. Childhood GERD is a risk factor for GERD in adolescents and young adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:806–812.

van der Pol RJ, Smits MJ, van Wijk MP, Omari TI, Tabbers MM, Benninga MA. Efficacy of proton-pump inhibitors in children with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2011;127:925–935.

Tsou VM, Baker R, Book L, et al. Multicenter, randomized, double-blind study comparing 20 and 40 mg of pantoprazole for symptom relief in adolescents (12 to 16 years of age) with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2006;45:741–749.

Gold BD, Gunasekaran T, Tolia V, et al. Safety and symptom improvement with esomeprazole in adolescents with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:520–529.

Haddad I, Kierkus J, Tron E, et al. Efficacy and safety of rabeprazole in children (1–11 years) with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57:798–807.

Eisai. Aciphex (rabeprazole) delayed release tablets. Full prescribing information. In: Eisai Pharmaceuticals I, ed., Tokyo; 2009.

Lee JH, Kim MJ, Lee JS, Choe YH. The effects of three alternative treatment strategies after 8 weeks of proton pump inhibitor therapy for GERD in children. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:9–13.

Takeda. Dexilant (dexlansoprazole) delayed release capsules. Full prescribing information. In: Takeda Pharmaceuticals America I, ed., Deerfield, IL; 2016.

Kukulka M, Wu J, Perez MC. Pharmacokinetics and safety of dexlansoprazole MR in adolescents with symptomatic GERD. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:41–47.

Takeda. Safety and efficacy of dexlansoprazole delayed-release capsules in treating symptomatic non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease in adolescents. ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet] 2014. https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01642602. Accessed July 27, 2016.

World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191–2194.

International conference on harmonisation of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use. ICH harmonized tripartite guideline: guideline for good clinical practice. J Postgrad Med. 2001;47:45–50.

Kleinman L, Nelson S, Kothari-Talwar S, et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of 2 age-stratified versions of the Pediatric GERD Symptom and Quality of Life Questionnaire. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:514–522.

Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R, Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–1920. (quiz 1943).

Sherman PM, Hassall E, Fagundes-Neto U, et al. A global, evidence-based consensus on the definition of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the pediatric population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1278–1295. (quiz 1296).

Brown EG, Wood L, Wood S. The medical dictionary for regulatory activities (MedDRA). Drug Saf. 1999;20:109–117.

Pace F, Scarlata P, Casini V, Sarzi-Puttini P, Porro GB. Validation of the reflux disease questionnaire for an Italian population of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:187–190.

Bland JM, Altman DG. Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ. 1997;314:572.

van Pinxteren B, Sigterman KE, Bonis P, Lau J, Numans ME. Short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD002095.

Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308–328. (quiz 329).

Vakily M, Zhang W, Wu J, Atkinson SN, Mulford D. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a known active PPI with a novel dual delayed release technology, dexlansoprazole MR: a combined analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:627–638.

Kukulka M, Eisenberg C, Nudurupati S. Comparator pH study to evaluate the single-dose pharmacodynamics of dual delayed-release dexlansoprazole 60 mg and delayed-release esomeprazole 40 mg. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2011;4:213–220.

Fass R, Chey WD, Zakko SF, et al. Clinical trial: the effects of the proton pump inhibitor dexlansoprazole MR on daytime and nighttime heartburn in patients with non-erosive reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:1261–1272.

Ford AC, Moayyedi P. Treatment of chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. BMJ. 2009;339:b2481.

Quigley EM. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-spectrum or continuum? QJM. 1997;90:75–78.

Funding

This trial was sponsored by Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Medical writing assistance was supported by Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A., Inc. and was provided by Neil Patel, PharmD, and Bomina Yu, PhD, CMPP, of inVentiv Medical Communications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in preparation of the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Betsy Pilmer was an employee of Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceuticals America, Inc. Barbara Hunt and Maria Claudia Perez are employees of Takeda Development Center Americas, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceuticals America, Inc. Benjamin D. Gold was a consultant for Takeda Pharmaceuticals of North America. Jaroslaw Kierkuś and David Gremse have no relevant disclosures.

Ethical approval

This research involved human participants and was conducted according to the principles described in the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonization Harmonized Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. Patient assent and parent/guardian consent were obtained prior to commencement of study procedures. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Boards and Independent Ethics Committees.

Additional information

Guarantor of the article: Benjamin D. Gold.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gold, B.D., Pilmer, B., Kierkuś, J. et al. Dexlansoprazole for Heartburn Relief in Adolescents with Symptomatic, Nonerosive Gastro-esophageal Reflux Disease. Dig Dis Sci 62, 3059–3068 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-017-4743-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-017-4743-3