Abstract

Transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) youth are the focus of media attention, policy and practice changes, and multidisciplinary research. Due to their disproportionate risk of self-harm, depression, and suicidality, family support of TGNC youth is a key focus. Despite growing community awareness, TGNC children, and their families, continue to navigate a complex myriad of challenges, including at an individual, family, community, and societal level. Parents are likely influenced by their child’s TGNC identity however little is known about how this parenting experience is perceived and navigated, with most research exploring the TGNC person’s perspective. Using qualitative photovoice methodology, this study explored the lived experience of raising a TGNC child from the parent perspective. Eight Australian parents of a TGNC young person aged between 10 and 18 years participated in an in-depth interview guided by their chosen photographs as the stimulus. Thematic analysis identified five key findings: 1. crossing the threshold: finding out and figuring it out; 2. changing and adapting; 3. same but different: attachment and family dynamic; 4. letting go and holding on; and 5. finding a path forward. Findings suggest complex psychosocial impacts on parenting. Recommendations include targeted support for parents that addresses grief, social isolation, career stress, and access to relevant information and services. Clinical social workers can play a vital role in supporting parents of TGNC children by providing trauma informed responses that recognise disenfranchised grief, acknowledge socioemotional impacts, and empower parents with appropriate resources to meet their needs, and those of their TGNC child.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Gender identity can be defined as “…a person’s deeply felt, inherent sense of being a girl, woman, or female; a boy, a man, or male; a blend of male or female; or an alternative gender” (American Psychological Association, 2015, p. 834). Transgender and Gender Nonconforming (TGNC) is a broad term for people whose gender identity is different to that which they were assigned at birth. In recent years, TGNC people have been the focus of media attention, political commentary, research, and policy changes on a global scale. The increased visibility of TGNC people in public discussion and popular media has aided to de-pathologise and normalise gender diversity but has also encouraged public debate on the inherent rights of TGNC people and incited transphobic responses (Pang & Steensma, 2022). TGNC people continue to experience disproportionate risk of self-harm, depression, and suicidality (Strauss et al., 2021). Children and young people are particularly impacted by these psychosocial vulnerabilities and TGNC individuals aged 14–25 are 15 times more likely to attempt suicide than the general population in Australia (LGBTIQA+ Health Australia, 2021). Globally, TGNC people experience increased biopsychosocial risk, discrimination, violence, exclusion, and poor psychological and behavioural health outcomes. These risks are undoubtedly systemic in nature, making TGNC wellbeing a critical concern for clinical social workers.

TGNC children, youth, and their families continue to navigate a complex myriad of challenges at individual, family, community, and societal levels (Capous-Desyllas & Barron, 2017). Parents and caregivers of TGNC youth play a key role in shaping the environment for their children’s identity development (Riggs et al., 2020). Parental support can mediate adolescent wellbeing and adolescent-parent relationships (Bhattacharya et al., 2021), and TGNC adolescents who have supportive families are more likely to demonstrate resilience and positive mental health (Olson et al., 2016). Despite the integral role of parents in TGNC young people’s lives, limited research has explored how parents navigate raising TGNC children. Understanding the parenting experience is important, as parental socioemotional wellbeing shapes that of the child (Bhattacharya et al., 2021). Exploring how parents can facilitate a secure base for their children and respond to the stressors associated with their unique experience of gender incongruence could aid in developing support for parents and increasing protective factors for TGNC children and young people.

This phenomenological qualitative study explored the lived experiences of Australian parents raising TGNC adolescents. To do this, the following research questions were asked: 1. What are the lived experiences of parents raising a TGNC child? 2. How does the child’s gender identity development influence the relationships and attachment within the family? 3. What stressors do parents experience due to their child’s TGNC transition? 4. How do parents navigate their child’s TGNC development and what support do they receive and would like to receive?

Method

A phenomenological qualitative approach was used to uncover new insights about this complex phenomenon whilst empowering individuals to voice their experiences (Taherdoost, 2022). Given the complexity and uniqueness of the TGNC parenting role, approaching this study from a qualitative foundation encouraged the collection of rich data that would have been difficult to obtain from a quantitative inquiry.

Ethical approval was provided by the University of the Sunshine Coast Human Research Ethics Committee. Approval number A221798.

Participants

Participants were recruited between April and October 2023 through purposive and snowballing techniques, with flyers distributed on social media, in community centres, and social groups likely to attract parents. Eligible participants were over 18 years of age, Australian residents, English speaking, and were parenting a TGNC child between the ages of 10 and 18 at the time of data collection. Eight parents (two fathers and six mothers) ranging in age from 33–54 years (M = 46.5, SD = 6.74) participated in the study. Five participants were married, two divorced, and one separated. All participants had either two or three children aged between 10–25 years (M = 16.82, SD = 4.32). Three participants indicated their religious/spiritual affiliation as Anglican, four as Agnostic, and one as Wiccan.

Photovoice Methodology

As the experience of TGNC is very personal and stigmatised, photovoice methods were used to establish an empowering and participant-led environment to explore lived experiences. Photovoice is a participatory method underpinned by critical education, feminist thought, and community development principles and encourages participants to share their lived experiences through photography (Wang & Redwood-Jones, 2001). Photovoice has previously been used to explore the lived experiences of LGBTIQA + students and parents of TGNC children in the USA (Bauer et al., 2019). Photovoice studies generally follow a nine step process: (1) select audience of policy makers or community leaders, (2) recruit participants, (3) train participants on the photovoice methodology, (4) informed consent, (5) determine photograph themes, (6) camera distribution and use, (7) photographs taken by participants, (8) share and discuss photographs, and (9) share photographs and narratives in an event with participants and policy makers or community leaders (Wang & Redwood-Jones, 2001). For this study, the audience was selected as community leaders in child and adolescent mental health services.

Following recruitment, participants were provided with a research information sheet, consent form, and photography guide and asked to take five photographs that symbolised their experience of parenting their TGNC child. The photographs were used as a stimulus to guide the interview. Semi-structured interviews of approximately 60 min duration took place through Zoom (n = 4) or in person (n = 4) based on participant preference. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by authors one and two before being deidentified and analysed. Whilst photovoice studies generally aim to share photographs in a collaborative event with both participants and policy makers/community leaders present, ethical approval to facilitate a gallery exhibition was denied due to the risk of parents sharing images of their children, and thus the authors amended the final stage of the study and presented the photographs and narratives at a conference where community leaders in child and adolescent mental health were in attendance.

Rigour

Due to the qualitative nature of this study, it is crucial to note the positionality of the researchers and consider how this would inform data analysis (Fischer & Guzel, 2023). All researchers identify as white, cis-gendered females. Three authors are parents to cis-gendered children and acknowledge that their parenting experiences may differ from those of participants. Rigour was applied in this study by purposeful reflexivity, peer review in analysis, and transparency through accurate, complete, and methodical reporting (Fischer & Guzel, 2023). This study reached data saturation with eight participants.

Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was carried out using NVivo14 software. Authors one and two independently engaged in data emersion and systematically read through all interview transcripts. Inductive coding was carried out to provide a broad analysis of the data, with rounds of coding resulting in categories that responded to the research questions (Linneberg & Korsgaard, 2019). The authors communicated regularly to ensure consistency and to mitigate personal bias (Fischer & Guzel, 2023). The first round of coding resulted in an initial 27 codes. Round two of coding grouped these codes together into five over-arching themes and 23 sub-themes, before final analysis resulted in five themes and 13 sub-themes.

Findings

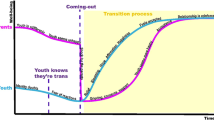

Thematic analysis of the data identified five key themes: 1. crossing the threshold: finding out and figuring it out, 2. changing and adapting, 3. same but different: attachment and family dynamic, 4. letting go and holding on, and 5. finding a path forward. Within these themes were 13 sub-themes (see Fig. 1).

Crossing the Threshold: Finding Out and Figuring It Out

Finding out about their child’s TGNC identity was a different journey for each parent. The age of their child when ‘coming out’ as TGNC ranged from 8 to 17 years. How parents found out varied, as did their initial responses. Some participants described their child approaching them directly or sharing their ‘coming out’ in a letter, as Evan explained, “…Ivy…she gave us a letter to read…”. For other parents this was less formal, as Caroline described; I don’t know how it came about…But it was just half in the house, half out of the house… kids running amuck… kind of, ‘Mum, how do you think I would know if I was nonbinary?’”. When reflecting on the experience of discovering their child’s gender identity, the parents spoke of ‘shock’, ‘surprise’, and significant change and transition. For most parents, finding out was followed by a process of ‘figuring it out’, through which they reached a point of acceptance and a realisation that life could return to ‘normal’. As Harvey described when sharing his photo (Fig. 2) of a timber door threshold “You go into a real kind of liminal period…you know? When David came out to us [as transgender]…there’s this period where you’re in between things. But then you get to the other side of that, and things are fine”.

Harvey’s experience reflected that of other parents, who described a ‘new normal’ and a transitional phase for both parent and child. For some parents, TGNC was a concept that they had no prior knowledge of, “at the beginning I had lots of thoughts and questions and there were lots of unknowns for us about the transgender experience” (Delilah). For others, TGNC was a familiar concept prior to their own child ‘coming out’, “My colleague at the time was a trans person…and a very good friend of mine, their child transitioned.” (Evan).

Another Piece of the Puzzle

The participants described their child’s gender identity as just once facet of a complex ‘puzzle’. Most parent’s children had experienced mental health challenges that preceded, and for some further complicated, their TGNC journey. For many parents, their child ‘coming out’ as TGNC provided an explanation for their struggles and a sense of a way forward. As Harvey described, his child “… suddenly started having these bouts of like depression…” which reflected the experience of Ramona who shared, “as they got older and hit their teens they had a few years of being quite unhappy. It was really difficult to know exactly why they were so unhappy. They were really quite low”. As Anna shared when reflecting on her photograph of scissors (Fig. 3), low mood and self-harm were experienced, “There was cutting…a crosshatch of cutting on her back which I found accidentally. I questioned her on why she was doing this to herself … she said, “I’m afraid that I’m a girl”.

Multiple families’ children were also navigating autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and/or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). As Anna expressed, her child experienced a complex interplay of challenges, “[there were] mental health issues, and some other diagnosis, autism, ADHD. Lots of other things going on that we kind of were navigating”. For some parents of TGNC children, ASD influenced and further complicated gender identity, as Ramona explained, “(they have) very black and white thinking (about gender norms) which goes hand and hand with ASD”. As these participants expressed, gender identity was not the only significant factor in their child’s wellbeing, “She’s grown up with a lot of crap. Not just the trans stuff, a lot of other stuff as well.” (Fiona), “…homelife was a little bit unsafe…I discovered that they were not a big fan of my ex (partner)” (Ramona), and “…she was physically unwell, so she was home on bedrest. She was…very underweight. A sick kid.” (Anna).

Family Reactions

As parents navigated their child’s ‘coming out’ as TGNC, most parents shared their child’s gender identity with their extended family. This experience often caused parents to feel worried about family reactions and generated anxiety, as Delilah described, “Is this gonna break apart our family? Are they not going to speak to us?”. Telling extended family was a decision that was often led by the child, which was challenging for some parents who had to ‘hide’ the truth from family, avoid discussing the child, and interchange between pronouns and new names when outside of the family home, as Anna explained;

One of those learning curves is me mentioning [TGNC] to family members before she was ready. That caused a big problem. We were put in situations where at home we had to use a particular gender and name and socially, or with family, we had to use a different gender and name.

Reactions from extended family were largely supportive, which was reassuring for families as described by these participants, “I eventually wrote a letter and sent it…all were supportive. We didn’t have any sort of negative reaction.” (Delilah) and “we’ve had phone calls from people to say… this is fantastic. You know, wish Abby all the best…. So, it’s been… good for us…for Abby to know that friends and family [are supportive].” (Anna). Despite these positive experiences, some participants described a lack of family support and ongoing trepidation about sharing their TGNC child’s experiences with others as Caroline explained, “there are some people that it’s not safe for us to tell which is rough”.

Changing and Adapting

Parenting a TGNC child resulted in a need to navigate change and create a ‘new normal’ that embraced the child’s identity. Parents needed to adapt to the changing biopsychosocial needs of their child, advocate for adjustments at school, and adopt a new name and pronouns for their child. The need to quickly and seamlessly adapt was reiterated by parents, who described a strong desire to ‘do what it takes’ to support and affirm their child, despite the pressure this placed on the parents themselves.

A New Normal

Parents described a need to quickly and smoothly adapt to a new way of life involving appointments, trialling medications, changing names and pronouns, and learning to advocate for their child. Most parents were actively involved in the medical care of their child as these participants described, “We managed to get her into a GP at (specialist center), which is trans place. It’s private, so it costs us, but you do what you do? So, she sees that GP for her medicine and transitioning.” (Fiona), and “We traveled the path of being diagnosed so that you can access hormone therapy and so on, which meant visits with psychologists and various doctors and all that whole process. So, we traveled with her along that way.” (Evan). This ‘new normal’ was often a period of adjustment, and as Anna described when sharing her photograph (Fig. 4), it required a “… whole heap of balancing that we had to do. I’ve had to ‘become one’ with medication. This is another transition for me as a parent… I never… thought I would have a child that is on…a range of medications.”.

A key place of change and advocacy was within the schooling system. Parents described proactive engagement with their child’s school to advocate for their changing needs. Many parents found school staff to be supportive and child-focused, as Ramona shared, “[the school was] very supportive…[the deputy principal] was very open to any further conversations or help from counsellors or assistants or whatever Eddy wanted. It was all very much led by Eddy and that’s how Eddy wanted to be”. Most parents identified school as a place of significance to their child’s wellbeing. Parents expressed concern about how their child would be perceived and treated by staff and peers, and whether issues such as bullying, misgendering, using incorrect names or pronouns, and access to gender appropriate facilities and uniforms would be experienced by their child. As Delilah shared, fear of school responses to a child’s gender transition was present, “How are we going to be judged? It was a Christian school …all those sorts of balancing acts between clothing and name and when do we change all those things for David’s mental health. How can we support him?”.

Transitioning: A Change

Most parents described a period of adjustment to their child’s appearance, name, and pronoun changes. Parents described a strong desire to affirm their child but acknowledged this to be a dynamic and confusing process. Parents explained that misusing pronouns or using an old name for their child resulted in hypervigilance, guilt, and anxiety about misgendering their child, as these participants experienced, “I’d find myself [being] so conscious of pronouns that on even sometimes you’re thinking, oh, did I call dog the right pronoun (laughs)?” (Harvey), and “She gets upset at us. Yeah… when we’re getting something wrong… accidentally calling her by her previous name…we try to be careful about that.” (Evan). Parents described the importance of what a name meant to their child, as Ramona explained, “Eddy very much said that Amanda was a ‘dead name’ and, it made them feel really, really sad inside. Like it gave them pain to hear it”. Worry was expressed about “making a mistake”, as Anna acknowledged, “There was a massive fear for all of us, including my younger child… in getting [the name] wrong”.

Same but Different: Attachment and Family Dynamic

Participants described their attachment bond with their child to have either remained stable, or strengthened, after ‘coming out’ as TGNC. Parents indicated little change to family relationships, yet many found siblings proactively took on supportive roles of their TGNC siblings.

Bond and Attachment

Most parents explained that their attachment to their child had not significantly changed due to their TGNC identity. Some parents described a perceived stronger attachment with their TGNC child since their ‘coming out’ as these participants shared, “I’ve probably become a bit more protective” (Grace), and “She comes to me a lot more now. To talk about things.” (Fiona). But for most participants, perceived bond and attachment with their TGNC child had not changed due to their child’s gender identity, “I don’t think our relationship changed at all” (Delilah), and “I don’t really think it’s changed it. I wouldn’t say we’re closer or less close, you know?” (Evan). When reflecting on their relationship with their TGNC child, parents noted ways in which they maintained their positive connection with their child, as Ramona described, “We connect a lot. We have very similar jokes and ways of connection. I think the fact that we already had a good relationship already [helped]”. Overwhelmingly, there was an acceptance of the child, regardless of their gender identity, as Delilah explained, “he was exactly the same person as he always was”. Ultimately, parents viewed their child as a person that they loved, rather than a son or daughter that they loved.

Family Dynamics

For some participants, their child’s TGNC identity had influenced dynamics and social roles within the family unit. Participants described changes to sibling relationships and roles, with some siblings perceived as becoming more protective of their TGNC family member, as Delilah explained “I asked how girls reacted to the dress… Eloise said they better be okay with it because if they weren’t they would meet her fist, and this was the first time I’d ever seen her get protective of (TGNC child)”. Participants described their other child/children as being supportive of their TGNC sibling, as Fiona shared, “when we explained it to (sibling), he was just like, ‘Yeah, okay and so what?’ and he started saying ‘she’ and ‘her’ and started going mad at us when we slipped up”. Some spouses experienced changes to parenting roles within the family, as Anna explained, “As far as dynamics within the family… Dave is better at doing the specialist stuff. The dynamic that Abby and he have together, it’s better to go up to a specialist and get the information”.

Letting Go and Holding On

Parents experienced a broad array of emotional reactions in response to their child’s TGNC journey. The process of ‘coming out’ and transitioning (either socially and/or medically) involved a complex dichotomy of ‘letting go’ of expectations and plans, whilst also ‘holding on’ to their connection with their child. Participants described dissonance, grief, fear, and acceptance as shaping their TGNC parenting experience.

Dissonance

Parents experienced dissonance in conflicting thoughts and feelings about their child’s transformation. Feelings of both love/acceptance and concern/rejection of their child’s TGNC identity was experienced by some of the parents, as Harvey described “When… David came out I was supportive. But…even though I knew transgender people… there was a part of me that was… I don’t know how to describe it… not willing to be so totally supportive”. Such feelings of dissonance often resulted in guilt, as Grace expressed;

I did, and at stages still do, hope that he is gay and not transgender. I feel it would be easier to navigate for him, and, yes, me... and I’m scared of losing my son. If he [medically] transitions it’s going to be a long physical, emotional and mental journey for him and us. I know that I will have to allow myself to grieve the loss of my son, while at the same time, embrace a new daughter. It’s daunting and scary. I have felt guilt. It’s a rollercoaster emotionally and mentally.

Grief

Although parents actively supported their children in their transitions, most parents expressed grief related to losing a life they had imagined. Grief was expressed when thinking about the future, as these participants shared, “You have to let go of everything you know…and you feel sad. I mean, I won’t have my daughter walking down the aisle.” (Ramona) and “it’s mostly…things like grandkids and just the future…that there was a way things might have gone. There is grief about that” (Evan). Grief was also expressed about the past, particularly changing the child’s name and, in some cases, the fond memories of childhood. As Evan described, birth certificates and name changes led to feelings of sadness, “…this is the sad point for [wife]. She loved that birth certificate. That, to her, is a moment of grief. Some people might perceive [name change] as a rejection of a thing that you chose”. Evan went on to explain the grief experienced when removing family photos from the home at the request of his child;

If dead naming is about using the person’s previous name, these pictures were kind of dead pictures... to be confronted with that previous self. So, you’re dealing not just with grief of things to come, but also how you can treat your previous experience and how your memories can be structured…how your memories can be felt about.

A sense of letting go of gender, whilst holding on to the child was expressed by parents, as Harvey described when reflecting on his photograph (Fig. 5) “there’s that feeling… am I losing someone? And over time, no… the relationship’s there. Gender is important, but there’s also a point where I (realised) actually gender is starting to be less of an issue”.

Fear

Fear was expressed by many parents, particularly when thinking about their child’s future. As Grace explained, fear was experienced when navigating how best to support her TGNC child, “It was panic. I want to help him, but don’t know how. Do something? Do nothing? I don’t know what to do. I would get myself so worked up and sad. I didn’t want to do it wrong”. Participants indicated that fear for the future was often related to how they, and their child, would be perceived and treated by others. Participants shared, “…anxiousness about the future…worry about how they will be received every day… every day of their lives.” (Evan), “I can’t make the world safe for her.” (Fiona), and “how are we going to be judged?” (Delilah).

Acceptance

Many parents described a certain acceptance and peace with their child’s TGNC identity and the TGNC parenting journey. Acceptance was connected to descriptions of unconditional positive regard, as Ramona shared, “When it’s your child, you love them. You just love them as a person”. For many parents, removing the concept of gender from the way in which they viewed their child, encouraged feelings of normalcy and acceptance, as Harvey shared, “you start questioning [gender]. What’s that mean? This person, you know, this person’s changed their gender identity but they’re still the same person!” and as Caroline described when reflecting on her photograph (Fig. 6), “When Charlie is asked about their gender identity, they say that it’s as irrelevant as cheese. All cheese is awesome! They don’t want to choose just one”.

A similar sentiment was shared by Delilah, who explained that gender did not define her child, “His personality is the same. I mean, a name changed and then down the road the hormone treatment and looking a bit different. But he was the same person. And I think that makes it much easier to accept”.

Finding a Path Forward

Parents navigated their TGNC parenting journey by drawing on their strengths and supports and proactively knowledge seeking. The TGNC parenting experience was described as one that got easier with time and involved a process of acceptance, connection building, knowledge acquisition, and parental growth. After initial shock and concern, parents described the ‘path forward’ as hopeful, albeit an isolated journey.

Drawing on Strengths and Supports

Parents relied on internal and external strengths such as resilience, lived experience, faith, family, online support, and to a lesser extent, formal service providers. Support was sought from family and friends, as Anna described when sharing her photograph (Fig. 7), “we’ve got support now…those family members that we’ve been able to share with and now friends as well”. Others sought support among faith networks, “a transgender priest who was a friend… I was able to sit down with her and her wife and talk about it, and I think that that was kind of helpful.” (Harvey). The support from communities of faith experienced by Harvey was also described by Delilah, ‘…we go to an Anglican church… they’re generally very supportive of gender diversity”.

Overwhelmingly, support accessed by parents to manage their own experiences and needs was largely informal, as reflected by Harvey, “No. Neither of us had, or were about, any sort of support, or network or anything. I guess I just rely on our family to be my support”. Of those interviewed, only one parent had engaged in formal support from a service provider (clinical social worker), “I’ve been really lucky. I have support from a mental health social worker. I think that should be just standard. I think it would be really great [for other TGNC parents]” (Anna). One parent had sought peer support online, but found this to be an unhelpful experience, “I joined a couple of nonbinary parents’ groups on Facebook. Horrible places. They did a bad job keeping the trolls [online bullies] out. I didn’t stay long” (Caroline).

All parents prioritised their child, rather than seeking out support for themself as a parent. Due to this focus on the needs of the child, some parents did not seek formal support, or discontinued support if their child did not wish to engage, as (Grace) explained, “We all went to the support group. It was good! I got insight from them and could hear them talking about their journey. We only went a couple of times, [TGNC child] didn’t want to go back anymore”. Some parents noted that the TGNC parenting journey was characterised by loneliness and isolation, as these participants shared, “I feel very lonely. Yeah, I don’t have any friends either. Like, I literally have nobody.” (Fiona) and “[TGNC parenting] is very isolating” (Anna).

Parents as Adaptive Learners

Parents drew on their strengths as adaptive learners. Books and independent research were used by parents to gain an understanding of their child’s experience, as Evan shared when reflecting on Fig. 8, “we did a lot of reading early on about this, both just online, buying various texts”.

Reading about others’ experiences developed parents’ knowledge and understanding of their child’s experience, as these participants experienced, “I read books and YouTube searching and reading other people’s stories and transgender people’s stories and their family’s stories” (Delilah). Whilst this quest for information was helpful for parents in terms of knowledge, skills building, and reassurance and normalisation, the process of finding accurate and relevant information was time-consuming and haphazard due to a lack of location specific resources that considered contextual factors such as laws, services, and supports.

Support: Barriers and Opportunities

Many parents felt isolated at the beginning of their child’s transition, not knowing who to go to for support or hesitant to seek help, as this participant explained, “I could have… but it I didn’t feel comfortable.” (Anna). Barriers to accessing support included difficulty finding information, inaccurate information, lengthy wait-times for services, and a reluctance to seek support in an effort to protect the TGNC child’s privacy. Several parents spoke of seeking support through specific gender clinics, both in the public and private health system. However, lengthy wait-times and financial cost were barriers to accessing this support, as Fiona shared, “The problem is the waitlist is ridiculously long…an eighteen-month waiting list. And by that time, she’ll have aged out. And then it’s like, well, what else do you do?”. Parents also identified that timely, location specific information was difficult to find, as Evan expressed when suggesting increased support, “…more literature. Or at least website material that was locally based. I would have found that helpful…information that was about the law in Queensland…like changing birth certificates, and so on.” (Evan). This perspective was shared by other parents, such as Caroline who suggested the need for “a workshop to explain everything… a website with [what] you need to know. A one-stop-shop”.

Discussion

Participants in this study portrayed parenting a TGNC child as a complex and unique experience that was influenced by a range of biopsychosocial factors. The experiences of the participants centred around discovering their child’s TGNC identity, sharing and navigating this transition with others, and negotiating a ‘new normal’. The lived experiences shared in this study suggest that parents may undergo their own socioemotional transformations and journey through cognitive/emotional processes that reflect those of grief and recovery models. This finding reflects that of Canitz and Haberstroh’s (2022) study, that found caregivers of transgender youth to experience ambiguous loss and disenfranchised grief in response to their child’s TGNC identity transition; a reaction to loss that is often devalued by society. Parents in the current study spoke of past, present, and future grief particularly in relation to name changes, memories, expectations, and plans. Despite expressing feelings of dissonance, grief, and fear, parents were reluctant to seek, or engage with, formal supports for themselves; instead reiterating a focus on the needs and wants of their TGNC child. It is important for clinical social workers to normalise parents’ feelings around grief and loss about their TGNC parenting experience and validate that these feelings can be present even while being supportive and accepting of their child. Clinical social workers can assist parents in creating a support system, developing stress management techniques, and establishing self-care routines. With this support, parents will be better equipped to ensure their own wellbeing and thus, that of their TGNC child.

Whilst positive parenting practices and parental acceptance have been shown to strengthen children’s wellbeing (Cui et al., 2018), a prioritisation of the needs of the TGNC child that overlooks the psychosocial needs of their parent could be detrimental to both parent and child. Intensive parenting was first proposed by Hays (1996) as a societally shaped cultural model of parenting that requires parents to be diligently child-focused, self-sacrificing, expert guided, and attentive to the child’s every need. As Field and Mattson (2016) forewarn, intensive parenting ideology, that arguably shapes contemporary parenthood through widespread moral pressure to parent in a child-centred manner, could influence parents of TGNC children more so due to their unique biopsychosocial needs and vulnerabilities. Field and Mattson (2016) warn of the isolation experienced by parents of TGNC children, who may be reluctant to seek support due to the pressure to respond in a ‘right’ and ‘moral’ way, as required in an intensive parenting society. For the parents in this study, support was often sought independently and in the form of information that could aid their support of their TGNC child, rather than seek support for themself as a parent. Intensive parenting ideology could also explain the fear of judgement that many of the parents in this study identified. Fear of family and broader societal reactions to their TGNC child was a key focus for parents, who felt a need to protect their child from the world. Individual counselling by clinical social workers can assist parents in examining their own needs, beliefs, and worries regarding the gender identity of their child and challenge dominant parenting paradigms that place overwhelming pressure and expectations on the parent. Family therapy can be carried out by clinical social workers to promote understanding, enhance communication, and strengthen family relationships.

The parents relied on social support from friends, family, and faith networks. Parents became active learners by reading books, articles and relying on social media for direction and advice. This finding reflects that of Matsuno et al. study (2022), where resources and clear communication facilitated parents’ ability to support their child. Parents in this study identified a need for specific education and resources that could be used to support their child. Parents also indicated that service availability and cost were barriers to timely support. Some were told that their child would ‘age out’ of the system before gaining care, which has been previously identified as a barrier for TGNC children (Bruce et al., 2023). Clinical social workers should provide parents with current, accurate information regarding gender identity, TGNC experiences, and barriers faced by TGNC children and families. By challenging systemic barriers and social stigma, clinical social workers can support parents of TGNC children to access timely and effective care that is responsive to their needs. Parents described internal dissonance, processing their negative/sad/hesitant thoughts and feelings, and grieving a life they thought they would experience. Hidalgo and Chen (2019) indicate that anxiety, worry, stress, social isolation, guilt, and feelings of loss were among the outcomes for parents of TGNC children, a finding that was reflected in the current study. Parents in this study described their child as experiencing a range of complex biopsychosocial issues in addition to their TGNC identity. Parents described complexity due to the intersect between gender identity and their child’s ASD and/or ADHD; a finding consistent with contemporary literature suggesting a co-occurrence of ASD, ADHD, and gender diversity (Heylens et al., 2018; Thrower et al., 2020). The experiences of parents in this study suggest a journey that is influenced by multiple identity dimensions, oppressions, and compounding minority identities. For the participants, their child’s gender expression was one piece of an identity ‘puzzle’, interwoven with other identity dimensions of sexual orientation, disability, and mental and physical health. By adopting an intersectional approach to therapy with TGNC children and their families (Golden & Oransky, 2019), clinical social workers can work to explore and challenge the myriad of identity challenges and adaptations that influence both parent and child; strengthening familial connections and building a shared understanding between parent and child about the intersection of identities and their influence on one another.

Parents in this study found accessing gender-affirming care challenging, which has also been identified previously (Chaplyn et al., 2023). Parents’ experiences in the school environment align with previous research, where parents advocate for their children and educate school staff on TGNC issues (Birnkrant & Przeworski, 2017; Capous-Desyllas & Barron, 2017). To shift this responsibility from individual parent to a collective challenge of oppression, clinical social workers can work with schools and community organisations to promote inclusive policies and practices that benefit TGNC children and nurture a safe learning environment.

Interestingly, parents perceived their attachment relationship to remain steady throughout their child’s gender identity transition; a noteworthy finding given the prevalence of insecure attachment for TGNC youth (Kozlowska et al., 2021). This finding is tentative however, given that the TGNC child’s perception of attachment was not explored. Future research that explores experiences of parents who are not supportive of their child’s gender identity is recommended, as these parent/child relationships are critical to the wellbeing of TGNC children and could shed light on necessary interventions to nurture affirming parenting.

Limitations

The study is limited by the lack of generalisability of the finding due to the small sample size and lack of diversity across the participants. The authors acknowledge that the sample represented parents who were (1) aware of their child’s gender identity, (2) affirming of their child, and (3) willing to reflect on, and speak about, their parenting experience. Another limitation is the amended approach to sharing the study findings in the participatory style of photovoice methodology. Due to challenges with gaining ethical approval for participants to share their photographs with the broader community, it was necessary for the authors to disseminate the photographs and narratives at a conference and by publication on the participants behalf.

Conclusion

This study explored the lived experiences of Australian parents raising TGNC children to better understand how their child’s gender identity influenced attachment and relationships within the family, what stressors parents experienced, how parents navigated this transition, and what supports they used or needed. It is acknowledged that the lived experiences of the participants do not represent those of all parents raising TGNC children and the study attracted a sample who have acknowledged/are aware and affirming of their child’s TGNC identity. Whilst the findings are not generalisable, they offer insight into how parents navigate parenting a TGNC child in Australia. This study found that parents experienced minimal change to attachment following their TGNC child ‘coming out’ and secure bonds were maintained through active advocacy, rethinking the importance of gender, remaining child-focused, and maintaining unconditional positive regard towards the child. However, a range of socioemotional challenges were experienced by the participants, who tended to minimise their own needs to prioritise those of their TGNC child. Clinical social workers can play a vital role in supporting parents of TGNC children by providing trauma informed care that recognises disenfranchised grief, acknowledges socioemotional impacts, and provides targeted information about legal procedures, medical treatments, and social support systems as they navigate the different phases of their child’s gender transition.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author Z Powell upon reasonable request.

References

American Psychological Association. (2015). Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. American Psychologist, 70(9), 832–864. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039906

Bauer, A., Franklin, J., Gruschow, S., & Dowshen, N. (2019). Photovoice: empowering transgender and gender-expansive youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(2), S5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.10.023

Bhattacharya, N., Budge, S. L., Pantalone, D. W., & Katz-Wise, S. L. (2021). Conceptualizing relationships among transgender and gender diverse youth and their caregivers. Journal of Family Psychology, 35, 595–605. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000815

Birnkrant, J. M., & Przeworski, A. (2017). Communication, advocacy, and acceptance among support-seeking parents of transgender youth. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 21(2), 132–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2016.1277173

Bruce, H., Munday, K., & Kapp, S. K. (2023). Exploring the experiences of autistic transgender and non-binary adults in seeking gender identity health care. Autism in Adulthood, 5(2), 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2023.0003

Canitz, S. N., & Haberstroh, S. (2022). Navigating loss and grief and constructing new meaning: Therapeutic considerations for caregivers of transgender youth. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 8(3), 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/23727810.2022.2133511

Capous-Desyllas, M., & Barron, C. (2017). Identifying and navigating social and institutional challenges of transgender children and families. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 34(6), 527–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-017-0491-7

Chaplyn, G., Saunders, L. A., Lin, A., Cook, A., Winter, S., Gasson, N., Watson, V., Wright Toussaint, D., & Strauss, P. (2023). Experiences of parents of trans young people accessing Australian health services for their child: Findings from trans pathways. International Journal of Transgender Health, 1(17), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2023.2177921

Cui, J., Mistur, E. J., Wei, C., et al. (2018). Multilevel factors affecting early socioemotional development in humans. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-018-2580-9

Field, T. L., & Mattson, G. (2016). Parenting transgender children in PFLAG. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 12(5), 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2015.1099492

Fischer, E., & Guzel, G. T. (2023). The case for qualitative research. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 33(1), 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcpy.1300

Golden, R. L., & Oransky, M. (2019). An intersectional approach to therapy with transgender adolescents and their families. Archives of Sexual Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1354-9

Hays, S. (1996). The cultural contradictions of motherhood. Yale University Press.

Heylens, G., Aspeslagh, L., Dierickx, J., Baetens, K., Van Hoorde, B., De Cuypere, G., & Elaut, E. (2018). The co-occurrence of gender dysphoria and autism spectrum disorder in adults: An analysis of cross-sectional and clinical chart data. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(6), 2217–2223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3480-6

Hidalgo, M. A., & Chen, D. (2019). Experiences of gender minority stress in cisgender parents of transgender/gender-expansive prepubertal children: A qualitative study. Journal of Family Issues, 40(7), 865–886. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19829502

Kozlowska, K., Chudleigh, C., McClure, G., Maguire, A. M., & Ambler, G. R. (2021). Attachment patterns in children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.582688

LGBTIQA+ Health Australia. (2021). Snapshot of mental health and suicide prevention statistics for LGBTIQ+ people. Retrieved from https://www.lgbtiqhealth.org.au/statistics

Linneberg, S., & Korsgaard, S. (2019). Coding qualitative data: A synthesis guiding the novice. Qualitative Research Journal, 19(3), 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-12-2018-0012

Matsuno, E., McConnell, E., Dolan, C. V., & Israel, T. (2022). “I am fortunate to have a transgender child”: An investigation into the barriers and facilitators to support among parents of trans and nonbinary youth. LGBTQ+ Family: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 18(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2021.1991541

Olson, K. R., Durwood, L., DeMeules, M., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2016). Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3223

Pang, K. C., & Steensma, T. D. (2022). negative media coverage as a barrier to accessing care for transgender children and adolescents. JAMA Network Open, 5(2), e2138623. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.38623

Riggs, D. W., Bartholomaeus, C., & Sansfaçon, A. P. (2020). ‘If they didn’t support me, I most likely wouldn’t be here’: Transgender young people and their parents negotiating medical treatment in Australia. International Journal of Transgender Health, 21(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2019.1692751

Strauss, P., Cook, A., Watson, V., Winter, S., Whitehouse, A., Albrecht, N., Wright Toussaint, D., & Lin, A. (2021). Mental health difficulties among trans and gender diverse young people with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD): Findings from Trans Pathways. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 137(2021), 360–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.03.005

Taherdoost, H. (2022). What are different research approaches? Comprehensive review of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method research, their applications, types, and limitations. Journal of Management Science & Engineering Research, 5(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.30564/jmser.v5i1.4538

Thrower, E., Bretherton, I., Pang, K. C., et al. (2020). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder amongst individuals with gender dysphoria: A systematic review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50, 695–706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04298-1

Wang, C., & Redwood-Jones, Y. (2001). Photovoice ethics: Perspectives from flint photovoice. Health Education and Behavior, 28(5), 560–572. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019810102800504

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. University of the Sunshine Coast, 101808544, Zalia Powell.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Powell, Z., Angeltveit, E., Davis, C. et al. Lived Experiences of Parenting Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Youth: Implications for Clinical Social Work Practice. Clin Soc Work J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-024-00936-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-024-00936-z