Abstract

This paper investigates the role that two key methodological choices play in the construction of dictionary-based indicators: the selection of local versus foreign newspapers, and the breadth of the press coverage (i.e. the amount of newspapers considered). The large literature in this field is almost silent about the robustness of research results to these two choices. These questions are relevant since the production of newspaper-based economic indicators is growing fast. We use as a case study the well-known economic policy uncertainty (EPU) index, taking as examples the six largest Latin American economies (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru) and Spain. First, we develop EPU measures based on press with different levels of proximity, i.e. local versus foreign, and corroborate that they deliver broadly similar narratives. Second, we examine the macroeconomic effects of EPU shocks computed using these different sources by means of a structural Bayesian vector autoregression framework and find similar responses from the statistical point of view. These two applications should reassure researchers that they can rely on foreign sources to construct EPU indexes. This option may foster the comparability of results across countries and lay the groundwork for cross-country studies of uncertainty. Finally, we show that constructing EPU indexes based on only one newspaper, an option followed by many studies, may yield biased responses. Increasing the number of sources reduces the chances of obtaining biased responses. This suggests that it is important to maximize the breadth of the press coverage when building text-based indicators, since this would improve the robustness and credibility of results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Notes

It was first calculated for the US and then constructed for other countries. The Policy Uncertainty website centralizes most EPU indexes based on the procedure of Baker et al. (2016).

This list is not exhaustive. Another strand of the literature relies on massive sources such as the entire Dow Jones news archives. We do not mention this literature since it is out of scope.

Separate results based on the Anglophone or Spanish press are available upon request.

Results for other relevant variables included in our empirical exercises are also similar, most notably as regards financial variables such as the exchange rate and a measure of financial risk.

For all countries except Brazil, we translate keywords from Spanish to English (for Brazil, we translate from Portuguese to English). Table 11 in Sect. B of the Appendix provides the list of keywords in Spanish and English.

The only exception is Infobae for Argentina. We included it because it is very popular in Argentina and we wanted to have at least 3 newspapers per country. Limiting the articles to those in the printed versions of the newspapers ensures the quality and relevance of the stories because editors select articles to be published in print given space limitations.

The time coverage of each newspaper is provided in Table 10 in Sect. B of the Appendix.

To define the Anglophone press, we rely on the newspapers considered by Barrett et al. (2022) to construct the Reported Social unrest index (RSUI), which consists in newspapers from UK, US and Canada.

For brevity, the list of keywords is reported in Table 12 in Sect. B of the Appendix.

Compared to the EPU indexes in Ghirelli et al. (2021), the indicators we present in this paper show two small technical differences: (i) we add a few new keywords that allow us to better capture the currency crisis in Argentina, and (ii) we select articles about the country of interest based on Factiva indexation rather than considering articles in which the name of the country appears in the text. This last choice is motivated by the fact that, especially in the Anglophone press, a news article may mention several Latin American countries even though it actually tells a story about one specific country. We check the robustness of our indicators to these technical changes, and it turns out that the results are very similar (available upon request).

For example, to avoid counting articles from Argentina in which the Argentinian press refers to the reactions of Chileans living in Argentina to the events in Chile in October 2019.

November 2002–December 2020 for the EPU index based on the local press; January 1997–December 2020 for the EPU index based on the foreign press, according to the availability of press data.

Frequency distribution for specific Latin American countries is not shown to avoid clutter. They are available upon request.

It is widely known that different newspapers may take opposite stances on economic issues (Lott & Hassett, 2014). This is due to the political or editorial bias of the newspaper and may exists also within local sources or within foreign sources.

For example, these could be events that are fully discounted by local newspapers, or whose effects are going to be less relevant or less controversial for the country examined than for the countries of origin of the foreign press.

To construct the macroeconomic variables at the level of the Latin American region, we take the simple mean of the variables across the six Latin American countries, in order not to over-represent Mexico and Brazil in the aggregate.

Results are robust to the inclusion of the Covid-19 period, but the impulse response functions are more unstable. Results are available upon request. In the context of vector autoregression (VAR) analysis, there is still no consensus on how to deal with the Covid-19 outlier encountered in most macroeconomic variables. Hence, shortening the sample is the most plausible approach for the purposes of this paper.

The VIX represents the market’s expectations regarding the relative strength of near-term price changes in the S &P 500 index. Because it is derived from the prices of S &P 500 index options with near-term expiration dates, it generates a 30-day forward projection of volatility.

In particular, it is a measure of the sentiment of global financial markets towards the country (a more reliable country attracts more flows).

For the computational implementation of the models, we use the developer version of the BEAR toolbox. For further details, see Dieppe et al. (2016).

For clarity, Fig.13 in Sect. F of the Appendix represents graphically the recursive identification à la Cholesky by means of a diagrammatic flow.

The coefficients of the impulse responses are also reported in Table 21 of the Appendix.

Results for single countries are available upon request.

The EMBI is calculated as the spread between US bonds and the emerging-market bonds. It is developed by JP Morgan Chase and is considered the main indicator of country risk for emerging markets.

Note, we focus on local newspapers since we already showed that the EPU index based on local press is equivalent to using the EPU index based on all available press, from a quantitative point of view. This choice is taken for simplicity, since if we considered the subset of all available press the number of possible combinations would explode.

Considering 7 (6) inputs, the number of possible combination without repetitions is 2 to the power of 7 (6) minus 1.

Given that some sources are available for shorter time spans, for Mexico and Brazil we drop out 7 combinations because the resulting EPU indexes that are too short due to text data availability.

The videos are available under https://github.com/eiae/EPU-press-analysis.

Note, the variation that emerges within each block refers to the specific selection of newspaper and may be due the editorial bias. This is out of hte scope of this paper.

This restriction implies that local variables are not Granger-causing global variables. Accordingly, we assume that Brazil, Mexico and Spain are small open economies when compared to the global variables considered in the models.

If the diagonal elements of D are left unrestricted, this can be done without loss of generality as to have mutually uncorrelated shocks with unit variances and as many structural shocks as variables in the model. Under this representation, a unit shock represents a magnitude of one standard deviation by construction.

A useful result is that when D is lower triangular so is \(D_0\).

References

Aguilar, P., Ghirelli, C., Pacce, M., & Urtasun, A. (2021). Can news help measure economic sentiment? An application in COVID-19 times. Economics Letters, 199, 109730.

Ahir, H., Bloom, N., & Furceri, D. (2019). The World Uncertainty Index. Working Papers 19–027, Standford Institute for Economic Policy Research.

Alexopoulos, M., & Cohen, J. (2015). The power of print: Uncertainty shocks, markets, and the economy. International Review of Economics & Finance, 40(C), 8–28.

Aprigliano, V., Emiliozzi, S., Guaitoli, G., Luciani, A., Marcucci, J., & Monteforte, L. (2022). The power of text-based indicators in forecasting Italian economic activity. International Journal of Forecasting.

Ardia, D., Bluteau, K., & Boudt, K. (2019). Questioning the news about economic growth: Sparse forecasting using thousands of news-based sentiment values. International Journal of Forecasting, 35(4), 1370–1386.

Armesto, M. T., Hernandez-Murillo, R., Owang, M. T., & Piger, J. (2009). Measuring the information content of the beige book: A mixed data sampling approach. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 41(1), 35–55.

Azzimonti, M. (2018). Partisan conflict and private investment. Journal of Monetary Economics, 93, 114–131. Carnegie-Rochester-NYU Conference on Public Policy held at the Stern School of Business at New York University.

Bachmann, R., Elstner, S., & Sims, E. R. (2013). Uncertainty and economic activity: Evidence from business survey data. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 5(2), 217–49.

Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., & Davis, S. J. (2016). Measuring economic policy uncertainty. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(4), 1593–1636.

Barrett, P., Appendino, M., Nguyen, K., & de Leon Miranda, J. (2022). Measuring Social Unrest Using Media Reports. Journal of Development Economics 158(102924).

Bloom, N. (2009). The Impact of Uncertainty Shocks. Econometrica, 77(3), 623–685.

Caldara, D., Fuentes-Albero, C., Gilchrist, S., & Zakrajšek, E. (2016). The macroeconomic impact of financial and uncertainty shocks. European Economic Review, 88, 185–207.

Caldara, D., & Iacoviello, M. (2022). Measuring geopolitical risk. American Economic Review, 112(4), 1194–1225.

Cerda, R., Silva, A., & Valente, J. T. (2018). Economic uncertainty impact in a small open economy: The case of Chile. Applied Economics, 50(26), 2894–2908.

Consoli, S., Barbaglia, L., & Manzan, S. (2022). Fine-grained, aspect-based sentiment analysis on economic and financial lexicon. Knowledge-Based Systems, 247, 108781.

Dieppe, A., Legrand, R., & Van Roye, B. (2016). The BEAR toolbox. ECB working paper, European Central Bank.

Fraiberger, S. P., Lee, D., Puy, D., & Ranciere, R. (2021). Media sentiment and international asset prices. Journal of International Economics, 133, 103526.

Garcia, D. (2013). Sentiment during Recessions. The Journal of Finance, 68(3), 1267–1300.

Ghirelli, C., Pérez, J. J., & Urtasun, A. (2019). A new economic policy uncertainty index for Spain. Economics Letters, 182, 64–67.

Ghirelli, C., Pérez, J. J., & Urtasun, A. (2021). The spillover effects of economic policy uncertainty in Latin America on the Spanish economy. Latin American Journal of Central Banking, 2(2), 100029.

Gil-León, J., & Silva-Pinzón, D. (2019). Índice de incertidumbre de política económica (EPU) para Colombia, 2000–2017. Ensayos de Economía, 29(55), 37–56.

Huang, Y., & Luk, P. (2020). Measuring economic policy uncertainty in China. China Economic Review 59(101367).

Jirasavetakul, L. -B., & Spilimbergo, A. (2018). Economic Policy Uncertainty in Turkey. IMF Working Papers 18/272, International Monetary Fund.

Jurado, K., Ludvigson, S. C., & Ng, S. (2015). Measuring uncertainty. American Economic Review, 105(3), 1177–1216.

Kalamara, E., Turrell, A., Redl, C., Kapetanios, G., & Kapadia, S. (2022). Making text count: Economic forecasting using newspaper text. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 37(5), 896–919.

Lott, J. R., & Hassett, K. A. (2014). Is newspaper coverage of economic events politically biased? Public Choice, 160(1/2), 65–108.

Mueller, H., & Rauh, C. (2018). Reading between the lines: Prediction of political violence using newspaper text. American Political Science Review, 112(2), 358–375.

Nyman, R., Kapadia, S., & Tuckett, D. (2021). News and narratives in financial systems: Exploiting big data for systemic risk assessment. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 127, 104119.

Papacharissi, Z., & de Fatima Oliveira, M. (2008). News frames terrorism: A comparative analysis of frames employed in terrorism coverage in U.S. and U.K. Newspapers. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 13(1), 52–74.

Pollak, S., Coesemans, R., Daelemans, W., & Lavrac, N. (2011). Detecting contrast patterns in newspaper articles by combining discourse analysis and text mining. Pragmatics, 21(4), 647–683.

Rambaccussing, D., & Kwiatkowski, A. (2020). Forecasting with news sentiment: Evidence with UK newspapers. International Journal of Forecasting, 36(4), 1501–1516.

Scotti, C. (2016). Surprise and uncertainty indexes: Real-time aggregation of real-activity macro-surprises. Journal of Monetary Economics, 82, 1–19.

Shapiro, A. H., Sudhof, M., & Wilson, D. J. (2022). Measuring news sentiment. Journal of Econometrics, 228(2), 221–243.

Thorsrud, L. A. (2020). Words are the new numbers: A newsy coincident index of the business cycle. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 38(2), 393–409.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the study conception and design, material preparation, data collection, analysis, writing, reviewing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank Concha Artola, Rodolfo Campos, Marina Diakonova, Angel Gavilán, Danilo Leiva, José M. González-Minguez, Margarita Machelett, Evi Pappa, Gabriel Pérez Quirós, Jacopo Timini, and seminar participants at Banco de España for comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Banco de España or the Eurosystem. Elena Vidal wrote part of this paper while affiliated at the Bank of Spain.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 A Data description

The data used to estimate the impact of policy uncertainty on macro and financial variables are sourced via Refinitiv. A complete description of the data is provided in Table 8.

In the case of quarterly data, real GDP series are taken from the NationaI Institute for Geography and Statistics of Brazil (IBGE in Portuguese), the National Institute of Statistics and Geography of Mexico (INEGI in Spanish) and the Oxford Economic database for Argentina, Chile, Colombia and Peru. Inflation is calculated from the respective domestic consumer price indexes, constructed and published by the respective national statistics offices. In both cases, we take the quarterly rate of change. Macro series are seasonally adjusted; we use Refinitiv to adjust for seasonality any series published without seasonal adjustment. The quarterly rates of each country are averaged to obtain the Latin American inflation and growth rates, thus avoiding the overweighting of Brazil and Mexico.

Net portfolio capital inflows from non residents are extracted from balance of payments publications of the respective national statistics offices and complemented with data from the IMF’s databases to build some series back to 2003. Capital flow series are scaled by the nominal GDP levels, and we avoid taking moving averages to reflect the direct impact of increases in EPU on the evolution of capital inflows and outflows. Latin American series are obtained adding portfolio capital flows.

The bilateral exchange rates vis–à–vis the USD are taken from Reuters. As there is no Latin American exchange rate against the US dollar, we take the quarterly changes in each exchange rate and average them for the six countries analysed. We use the benchmark MSCI equity indices in USD to estimate the change in stock prices, and although MSCI has a Latin American index, we prefer to extract the six individual indexes and calculate the average of the quarterly changes as the aggregate index is biased towards the evolution of the major firms of Brazil and Mexico, which have the highest market capitalization.

Finally, we include the VIX index, which represents the market’s expectations regarding price changes in the S &P 500 index. Because it is derived from the prices of Standard and Poor’s index options with near-term expiration dates, it generates a 30-day forward projection of volatility. The VIX is included in levels and attempts to capture global uncertainty, so it is useful to disentangle the effects of EPU shocks from the effects of international events that, in turn, could affect EPU.

The robustness exercise with monthly data uses the same variables as above but for the activity index and portfolio capital flows of non-residents. For the former, we use the monthly GDP proxies published by the national statistics offices and central banks of the region (Estimador Mensual de Actividad Económica (EMAE) for Argentina; Índice de Atividade Econômica do Banco Central (IBC-Br) for Brazil; Índice Mensual de Actividad Económica (Imacec) for Chile; Indicador de Seguimiento a la Economía (ISE) for Colombia; Indicador Global de la Actividad Económica (IGAE) for Mexico; and the INEI monthly GDP for Peru). In the case of portfolio flows by non-residents, the central banks of all countries except Peru publish monthly data.

1.2 B Constructing the EPU Indexes: Local Press Coverage by Country

1.3 C Narrative Across Alternative Press Coverage by Country

1.4 D Our EPU Indexes by Country

This section shows each country-level EPU index with its associated timeline of relevant events. In most cases, the peaks in the indexes are explained by events that might increase economic uncertainty in the country. This exercise is commonly used in the literature to provide evidence of the validity of the index as a proxy of economic uncertainty. Nevertheless, there are a few cases in which the spikes do not correspond to a relevant event in the country’s recent history. This is noise. Following the literature, we manually clean the series by replacing each of these noisy peaks with the average of each series. Below, we provide a list of all noisy peaks for each country.

-

Argentina: Jul. 2003, Jul. 2005 (foreign press)

-

Chile: Feb. 2021 (foreign press)

-

Peru: Sep. 2010, Jul. 2017 (foreign press)

1.5 E Our EPU Indexes for the Latin American Region

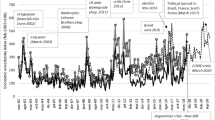

EPU indexes for the Latin American region. Note: This figure shows the EPU indexes for the Latin American region based on the local (red line) and foreign press (black line) against the narrative of events associated with increases in policy uncertainty in this region. The Latin American region is defined as the following countries: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru

1.6 F Structural VAR Model with Recursive Identification à la Cholesky

In this section we explain the details of our recursive identification strategy to identify structural shocks in our VAR models. First we present the model mathematically and then we illustrate the identification assumptions through a graphical representation.

The multivariate time-series model for periods \(t=1, \dots ,T\) consists of a \(n \times 1\) vector of variables \(\{y_t\}_{t=1}^T\), \(n \times n\) matrices of coefficients \(A_{i}, i = 1, \dots ,p\) capturing the dynamics of the pth lagged system, a \(n \times 1\) vector of constants C and an \(n \times 1\) vector of error terms \(\varepsilon _t\) with zero-mean and positive-definite \(n \times n\) covariance matrix \(\Sigma \). This data-generating process is assumed to evolve according to the following VAR(p):

The open-economy model contains variables for the global block (G) and for the local block (L) consisting of variables for Latin American countries like Brazil (BR) or Mexico (MX), and Spain (ES). Hence, in our benchmark specification we have \(y_t = \{y_t^{G}, y_t^{L}\}\), with \(L=(BR, MX, ES)\). Each superscript indicates a group of variables (five variables in total, one in the G group and four in the L group). In particular, we have \(y_t^{G} = VIX_t \) and \(y_t^{L} = (EPU_t, PCF_t, GDP_t, CPI_t)^\top \). The block exogeneity assumption entails imposing zero-restrictions on the coefficient matrices so to cancel out past effectsFootnote 34 of \(y_t^{L}\) on \(y_t^{G}\):

One might be interested in having an economic interpretation of the shocks, and for this, one needs to define the contemporaneous relationships between variables. Let \(D_{j}, j = 0, \dots ,p\) capture such structural relationships, K be the constants and \(\eta _t\) be the structural innovations with zero-mean and structural covariances \(\Gamma \). Therefore, the structural VAR(p) is given by:

As a result, the link between the reduced-form VAR and the structural counterpartFootnote 35 is established by \(A_i = D D_{i}\), \(C = D K\), \(\varepsilon _t = D \eta _t\), and \(\Sigma = D \Gamma D^\top \), with \(D = D_{0}^{-1}\). To recover the structural model from its reduced-form or disentangle \(\eta _t\) from \(\varepsilon _t\), one needs to adopt an identification strategy to restrict the contemporaneous matrix D.

This comes from the fact that for the system of equations in \(\Sigma = D \Gamma D^\top \) there are \(n^2\) elements to be identified in D and \(\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\) in \(\Gamma \) due to its symmetry about the diagonal. Once the structural covariance is normalisedFootnote 36\(\Gamma = I_n\), \(I_n\) being a \(n \times n\) identity matrix, there are just \(n^2\) elements left to identify. Since one can estimate from the reduced model \(\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\) distinct elements from \(\Sigma \), only \(\frac{n(n-1)}{2}\) additional restrictions on D are needed to just identify the system. For this purpose, we impose exclusion restrictions recursively, which implies finding a lower triangular matrix \(D \quad \text {s.t.} \quad \Sigma = D D^\top \). One way to achieve this is to apply the Cholesky decomposition of \(\Sigma = P P^\top \), with P being a \(n \times n\) lower triangular matrix with positive diagonal. It follows that \(P = D\) is one possible solution that satisfies the needed \(\frac{n(n-1)}{2}\) restrictions for exact identification.Footnote 37 Accordingly, we impose contemporaneous restrictions such that upper off-diagonal elements in D are zero.

Note that the ordering of the variables in both groups is crucial for this identification scheme since its recursive nature imposes a particular causal chain. The position of the variable in the ordering shows to which variables it is restricted to react to and to which variables it is restricted to affect in period t.

To illustrate this identification scheme we create a diagrammatic flow that explains graphically the assumptions underlying the recursive identification in Fig. 13. Each arrow represents the impact of the contemporaneous structural shock of one variable on the other variables in the system. As the graph shows, each variable affect contemporaneously itself. However, the ordering of the variable in the system implies that shocks of one variable affect all variables that are placed below, and do not affect variables that are ordered before. For instance, this means that shocks in the EPU affect contemporaneously the economy, but that shocks in the economy cannot affect contemporaneously uncertainty, but do it only with a lag (as specified by the model).

Graphical representation of the recursive identification à la Cholesky. Note: This diagrammatic flow represents the recursive identification à la Cholesky used to estimate the structural shocks in the structural VAR models. Each arrow represents the impact of the contemporaneous structural shock of one variable on the other variables in the system

1.7 G Robustness Results: BVAR Specifications

Robustness results: IRFs of GDP to EPU shocks for the Latin American region. Note: Each panel depicts the median impulse response of GDP to a rise of one standard deviation in the EPU index in the LATAM region: the red and blue lines represent responses to EPU shocks based on the local and foreign press, respectively. Filled symbols indicate statistical significance within the 84%–16% credible set, while empty symbols represent not-significant estimates. The horizontal axis measures quarters since the shock

Robustness results: IRFs of GDP to EPU shocks for the Latin American region using alternative financial variables in the model. Note: Each panel depicts the median impulse response of GDP to a rise of one standard deviation in the EPU index in the LATAM region: the red and blue lines represent responses to EPU shocks based on the local and foreign press, respectively. Filled symbols indicate statistical significance within the 84%–16% credible set, while empty symbols represent not-significant estimates. The horizontal axis measures quarters since the shock. PCF stands for portfolio capital flows

1.8 H Robustness Results: Breadth of Press Coverage

Robustness exercise regarding the breadth of press coverage. Note: Each chart reports on the vertical axis the percentage of coefficients of the response based on the EPU constructed from each combination of newspapers that are close enough (i.e. not statistically different) to the credible bands of the baseline responses. The horizontal axis shows the possible combinations of sources (56 for Brazil and Mexico, 127 for Spain), ordered increasingly depending on the number of sources (the black vertical line indicates each time the number of sources increases)

1.9 I Additional Benchmark Results: BVAR Exercise for the Latin American Region

Benchmark model: IRFs of GDP to EPU shocks with credible set. Note: The panels depicts the median impulse response of the specified variable to a rise of one standard deviation in the (a) local press and (b) foreign press EPU indexes, along with the corresponding 90%–10%, 84%–16% and 68%–32% credible sets (marked by decreasing colour intensity). The horizontal axis measures quarters since the shock. In both cases we estimate the model with portfolio capital flows as financial variable

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Andres-Escayola, E., Ghirelli, C., Molina, L. et al. Using Newspapers for Textual Indicators: Guidance Based on Spanish- and Portuguese-Speaking Countries. Comput Econ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10614-023-10433-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10614-023-10433-z