Abstract

We add to the investments literature by employing new techniques to estimate asset performance. We estimate a data envelopment analysis based efficiency score that allows for direct comparison between ex-post efficiency rankings and test the ex-ante relevance of such scores by including them into asset pricing models. We find that knowing the fund efficiency score can help explain time-series returns. When efficiency is included in an asset pricing model, the absolute value of the average mispricing error is decreased, which we take as evidence of the explanatory power of efficiency scores. But more importantly, we show that efficacy scores can be used as next period predictors of stock returns. In addition, we further use the efficiency scores to differentiate between the performance of constrained and unconstrained investment assets, as in the case of socially responsible investments. Our findings give robustness to the literature on constrained investments showing significant underperformance of socially and responsible investments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

SRI only invests in firms with high ethical principles and high social responsibility of business practices, where the common denominator is usually avoiding investing in alcohol, tobacco, gambling, pornography, and weapons. But the specific holdings of each fund depend on the managing firm; for example, Northwest and Ethical Funds Investing limit their assets to only those which meet their rigorous standards on environmental risk, social risk, and governance risk. Environmental risk Do the company’s activities have a negative impact on the air, land or water? We look into issues, such as biodiversity, land-use planning, emissions, climate change and water use; Social risk Does the company respect human rights and workers’ safety? Governance risk How is the company run? We look at factors such as board of director diversity, independence and executive compensation. www.ethicalfunds.com.

Alternatively, we also estimated a size-adjusted comparison between the monthly efficiency scores of ethical and traditional funds. The results show that traditional investments systematically score higher than ethical investments. This is further evidence of ethical funds underperforming unconstrained investment.

This is expected because funds invest in a finite number of assets. In fact, the pool of ethical assets is even smaller, thus having more interdependence of funds, which increases the need to estimate sample specific \(\chi ^{2}\) values.

Best practices, in this context, refer to those funds with the highest level of outputs given the prevailing level of inputs.

\(LPM0_j =\frac{1}{T}{\sum }_{t=1}^{{\tilde{T}} } 1 \; \); \(LPM0_j =1-UPM0_j \).

Looking at the correlation between I/O also supports choosing LPM0 instead of UPM0.

Just like Glawischnig and Sommersguter-Reichmann (2010), the results show high correlation among LPM2 and LPM3 (UPM2 and UPM3), as well as LPM2 and LPM4 (UPM2 and UPM4). Despite that high correlation, they are still incorporated into the model to apply an extra penalty/ benefit for higher moments due to non-normality of returns.

A test of differences in means was estimated but, for simplicity, it is not reported.

The difference is expected to be statistically significant given close inspection of monthly chi-square tests, but the test results are not reported for simplicity.

Earlier estimates looked at the monthly distribution of \(P^{\textit{BCC}}\) based on a 1-1 match between ethical and traditional investment for a 3000-iteration bootstrap. Results were congruent with these findings: ethical funds appear less efficient than traditional investment assets, consistently after 1990. Results are available upon request.

Even after deleting all money market mutual funds, the possibility of large debt holding is not removed. CRSP only reports the latest objective, and thus the fund could have historically had money market instruments. Furthermore, many funds rely in bonds.

The Social Investment Forum defines Sustainable and Responsible Investing as an investment discipline that considers environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) criteria to generate long-term competitive financial returns and positive societal impact. (http://www.ussif.org/).

Abstract taken from SIF’s Performance and SRI investments page: http://ussif.org/resources/performance.cfm; the full report on Sustainable and Responsible Investment trends can be downloaded from: http://ussif.org/resources/research/documents/2010TrendsES.pdf.

See Basso and Funari (2008), page 26 for further exemplification of social responsible screening.

Domini 400 Social Index: A market cap weighted stock index of 400 publicly traded companies that have met certain standards of social and environmental excellence. Potential candidates for this index will have positive records on issues such as employee and human relations, product safety, environmental safety, and corporate governance. Companies engaged in the business of alcohol, tobacco, firearms, gambling, nuclear power and military weapons are automatically excluded. http://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/domini_400.asp#ixzz26NyXf2Ft.

References

Ang, A., Chen, J., & Xing, Y. (2006). Downside risk. Review of Financial Studies, 19(4), 1191–1239.

Ang, J. S., & Chua, J. H. (1979). Composite measures for the evaluation of investment performance. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 14(02), 361–384.

Arditti, F. D. (1975). Skewness and investors’ decisions: a reply. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 10(01), 173–176.

Arditti, F. D., & Levy, H. (1975). Portfolio efficiency analysis in three moments: the multiperiod case. The Journal of Finance, 30(3), 797–809.

Ball, C. A., & Torous, W. N. (1983). A simplified jump process for common stock returns. Journal of Financial and Quantitative analysis, 18(1), 53–65.

Banker, R. D., Charnes, A., & Cooper, W. W. (1984). Some models for estimating technical and scale inefficiencies in data envelopment analysis. Management Science, 30(9), 1078–1092.

Barnett, M. L., & Salomon, R. M. (2006). Beyond dichotomy: The curvilinear relationship between social responsibility and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 27(11), 1101–1122.

Basso, A., & Funari, S. (2001). A data envelopment analysis approach to measure the mutual fund performance. European Journal of Operational Research, 135(3), 477–492.

Basso, A., & Funari, S. (2003). Measuring the performance of ethical mutual funds: A DEA approach. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 54(5), 521–531.

Basso, A., & Funari, S. (2005). A generalized performance attribution technique for mutual funds. Central European Journal of Operations Research, 13(1), 65.

Basso, A., & Funari, S. (2008). DEA models for ethical and non ethical mutual funds. Mathematical Methods in Economics and Finance, 2(1), 21–40.

Bauer, R., Koedijk, K., & Otten, R. (2005). International evidence on ethical mutual fund performance and investment style. Journal of Banking & Finance, 29(7), 1751–1767.

Bera, A. K., & Jarque, C. M. (1981). Efficient tests for normality, homoscedasticity and serial independence of regression residuals: Monte Carlo evidence. Economics Letters, 7(4), 313–318.

Blattberg, R. C., & Gonedes, N. J. (1974). A comparison of the stable and student distributions as statistical models for stock prices. The Journal of Business, 47(2), 244–280.

Bollen, N. P. (2007). Mutual fund attributes and investor behavior. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 42(3), 683. (Renneboog et al. 2005).

Campbell, J. Y., & Hentschel, L. (1992). No news is good news: An asymmetric model of changing volatility in stock returns. Journal of financial Economics, 31(3), 281–318.

Carhart, M. M. (1997). On persistence in mutual fund performance. The Journal of Finance, 52(1), 57–82.

Chang, K. P. (2004). Evaluating mutual fund performance: An application of minimum convex input requirement set approach. Computers & Operations Research, 31(6), 929–940.

Charnes, A., Cooper, W. W., & Rhodes, E., (1978, 1979). Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. European Journal of Operational Research, 2(6), 429–444.

Choi, Y. K., & Murthi, B. P. S. (2001). Relative performance evaluation of mutual funds: A non-parametric approach. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 28(7–8), 853–876.

Darling, G., Mukherjee, K., & Wilkens, K. (2004). CTA performance evaluation with data envelopment analysis. Commodity trading advisors: Risk, performance analysis and selection. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Diltz, D. J. (1995). The private cost of socially responsible investing. Applied Financial Economics, 5(2), 69–77.

Eling, M. (2006). Performance measurement of hedge funds using data envelopment analysis. Financial Markets and Portfolio Management, 20(4), 442–471.

Fama, E. F. (1965). The behavior of stock-market prices. The Journal of Business, 38(1), 34–105.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1992). The cross-section of expected stock returns. The Journal of Finance, 47(2), 427–465.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1993). Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 33(1), 3–56.

Fama, E. F., & MacBeth, J. D. (1973). Risk, return, and equilibrium: Empirical tests. The Journal of Political Economy, 81, 607–636.

Galagedera, D. U., & Silvapulle, P. (2002). Australian mutual fund performance appraisal using data envelopment analysis. Managerial Finance, 28(9), 60–73.

Geczy, C., Stambaugh, R., & Levin, D. (2005). Investing in socially responsible mutual funds. Available at SSRN 416380.

Gil-Bazo, J., Ruiz-Verdú, P., & Santos, A. A. (2010). The performance of socially responsible mutual funds: The role of fees and management companies. Journal of Business Ethics, 94(2), 243–263.

Glawischnig, M., & Sommersguter-Reichmann, M. (2010). Assessing the performance of alternative investments using non-parametric efficiency measurement approaches: Is it convincing? Journal of Banking & Finance, 34(2), 295–303.

Goldreyer, E. F., & Diltz, J. D. (1999). The performance of socially responsible mutual funds: Incorporating sociopolitical information in portfolio selection. Managerial Finance, 25(1), 23–36.

Gray, J. B., & French, D. W. (1990). Empirical comparisons of distributional models for stock index returns. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 17(3), 451–459.

Gregoriou, G. N. (2003). Performance appraisal of funds of hedge funds using data envelopment analysis. Journal of Wealth Management, 5(4), 88–95.

Gregoriou, G. N. (2006). Trading efficiency of commodity trading advisors using data envelopment analysis. Derivatives Use, Trading Regulation, 12(1), 102–114.

Gregoriou, G. N., & Chen, Y. (2006). Evaluation of commodity trading advisors using fixed and variable and benchmark models. Annals of Operations Research, 145(1), 183–200.

Gregoriou, G. N., & McCarthy, K. (2005). Efficiency of funds of hedge funds: A data envelopment analysis approach. Hedge Funds: Insights in Performance Measurement, Risk Analysis, and Portfolio Allocation. New Jersey: Wiley.

Gregoriou, G. N., Rouah, F., Satchell, S., & Diz, F. (2005). Simple and cross efficiency of CTAs using data envelopment analysis. The European Journal of Finance, 11(5), 393–409.

Guerard, J. B, Jr. (1997). Additional evidence on the cost of being socially responsible in investing. The Journal of Investing, 6(4), 31–36.

Hamilton, S., Jo, H., & Statman, M. (1993). Doing well while doing good? The investment performance of socially responsible mutual funds. Financial Analysts Journal, 49, 62–66.

Hanoch, G., & Levy, H. (1969). The efficiency analysis of choices involving risk. The Review of Economic Studies, 36(3), 335–346.

Haslem, J., & Scheraga, C. (2003). Data envelopment analysis of Morningstar’s large-cap mutual funds. Journal of Investing, 12(4), 41–48.

Ho, Y. K., & Cheung, Y. L. (1991). Behaviour of intra-daily stock return on an Asian emerging market-Hong Kong 1. Applied Economics, 23(5), 957–966.

Jarque, C. M., & Bera, A. K. (1980). Efficient tests for normality, homoscedasticity and serial independence of regression residuals. Economics Letters, 6(3), 255–259.

Jarque, C. M., & Bera, A. K. (1987). A test for normality of observations and regression residuals. International Statistical Review/Revue Internationale de Statistique, 55, 163–172.

Jensen, M. C. (1968). The performance of mutual funds in the period 1945–1964. The Journal of Finance, 23(2), 389–416.

Joro, T., & Na, P. (2006). Portfolio performance evaluation in a mean-variance-skewness framework. European Journal of Operational Research, 175(1), 446–461.

Kane, A. (1982). Skewness preference and portfolio choice. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 17(01), 15–25.

Kraus, A., & Litzenberger, R. H. (1976). Skewness preference and the valuation of risk assets. The Journal of Finance, 31(4), 1085–1100.

Kon, S. J. (1984). Models of stock returns–A comparison. The Journal of Finance, 39(1), 147–165.

Kurtz, L. (1997). No effect, or no net effect? Studies on socially responsible investing. The Journal of Investing, 6(4), 37–49.

Kurtz, L., & DiBartolomeo, D. (1996). Socially screened portfolios: An attribution analysis of relative performance. The Journal of Investing, 5(3), 35–41.

Lau, A. H. L., Lau, H. S., & Wingender, J. R. (1990). The distribution of stock returns: New evidence against the stable model. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 8(2), 217–223.

Leland, H. E. (1999). Beyond mean-variance: Performance measurement in a nonsymmetrical world. Financial analysts journal, 27–36.

Lim, S., Oh, K. W., & Zhu, J. (2014). Use of DEA cross-efficiency evaluation in portfolio selection: An application to Korean stock market. European Journal of Operational Research, 236(1), 361–368.

Lintner, J. (1965). The valuation of risk assets and the selection of risky investments in stock portfolios and capital budgets. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 47(1), 13–37.

Mandelbrot, B. (1963). The stable Paretian income distribution when the apparent exponent is near two. International Economic Review, 4(1), 111–115.

Markowitz, H. (1952). Portfolio selection*. The Journal of Finance, 7(1), 77–91.

Markowitz, H. (1959). Portfolio selection: Efficient diversification of investments (No. 16). New Haven: Yale University Press.

McMullen, P. R., & Strong, R. A. (1998). Selection of mutual funds using data envelopment analysis. Journal of Business and Economic Studies, 4(1), 1–12.

Morey, M. R., & Morey, R. C. (1999). Mutual fund performance appraisals: A multi-horizon perspective with endogenous benchmarking. Omega, 27(2), 241–258.

Moskowitz, M. (1972). Choosing socially responsible stocks. Business and Society Review, 1(1), 71–75.

Murthi, B. P. S., Choi, Y. K., & Desai, P. (1997). Efficiency of mutual funds and portfolio performance measurement: A non-parametric approach. European Journal of Operational Research, 98(2), 408–418.

Praetz, P. D. (1972). The distribution of share price changes. Journal of Business, 45, 49–55.

Press, S. J. (1967). A compound events model for security prices. Journal of Business, 40, 317–335.

Renneboog, L., Ter Horst, J., & Zhang, C. (2008). The price of ethics and stakeholder governance: The performance of socially responsible mutual funds. Journal of Corporate Finance, 14(3), 302–322.

Sauer, D. A. (1997). The impact of social-responsibility screens on investment performance: Evidence from the Domini 400 Social Index and Domini Equity Mutual Fund. Review of Financial Economics, 6(2), 137–149.

Sharpe, W. F. (1966). Mutual fund performance. The Journal of Business, 39(1), 119–138.

Simkowitz, M. A., & Beedles, W. L. (1980). Asymmetric stable distributed security returns. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 75(370), 306–312.

Smith, J. B. (1981). The probability distribution of market returns: A logistic hypothesis. Doctoral dissertation, Graduate School of Business, University of Utah.

So, J. C. (1987). The distribution of foreign exchange price changes: Trading day effects and risk measurement-A comment. The Journal of Finance, 42(1), 181–188.

Statman, M. (2000). Socially responsible mutual funds. Financial Analysts Journal, 56, 30–39.

Tobin, J. (1958). Liquidity preference as behavior towards risk. The review of economic studies, 25(2), 65–86.

Treynor, J. L. (1965). How to rate management of investment funds. Harvard Business Review, 43, 63–75.

Turner, A. L., & Weigel, E. J. (1992). Daily stock market volatility: 1928–1989. Management Science, 38(11), 1586–1609.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 A Description of Ethical Investing

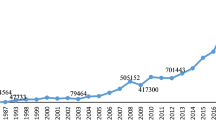

According to the Social Investment Forum in the U.S. (SIF), over the past 20 years the total dollars invested in SRIs has grown exponentially, as has the number of institutional, professional, and individual investors involved in the field. Between 1995 and 2010, total dollars under professional management in SRI grew from $639 billion to $3.07 trillion, outpacing the overall market. As of 2015, it has further increased to 6.57 trillion dollars.Footnote 13 SRI investing has become a mainstream asset, and as a result, a number of conventional companies now offer SRI products to their clients. An increasing number of investors focus on ethical funds not only because of the ethical aspect, but because returns are comparable to those of more conventional investments.Footnote 14

Managers of ethical funds have to follow socially responsible constraints on environmental risk, social risk, and governance risk. For example, they would not buy shares from the weapons, gambling, alcohol, or tobacco industries; nor would they buy shares from companies known for polluting the environment, using “sweatshops,” discriminating against their employees, etc. On the other hand, these managers would increase their number of shares of ethical companies, philanthropic institutions, and firms well known for their social activities.Footnote 15 This is the social screening process. Barnett and Salomon (2006) find that when the number of social screens (both positive and negative) increases, the fund’s annual return initially declines, but then rebounds as the number of screens reaches a maximum. Furthermore, SRI’s managers also have to analyze the companies’ financial statements. An example can be seen in Goldreyer and Diltz (1999) who find that the performance of ethical investment also depends on the level of financial screening.

The question still remains whether or not ethical investment reduces profitability, thereby reducing efficiency. Asked another way, are the risk-adjusted returns of SRI portfolios higher than traditional investing? In response to this matter, Hamilton et al. (1993) proposed three alternative hypotheses: (1) the risk-adjusted expected returns of socially responsible portfolios are equal to the risk-adjusted expected returns of conventional portfolios, as the social responsibility feature of stocks is not priced; (2) the risk-adjusted expected returns of socially responsible portfolios are lower than the expected returns of conventional portfolios, as the market prices the social responsibility characteristic by increasing the value of socially responsible companies relative to the value of conventional companies by driving down the expected returns and the cost of capital of socially responsible companies; and (3) (also suggested by Moskowitz 1972), the risk-adjusted expected returns of socially responsible portfolios are higher than the expected returns of conventional portfolios, as the market prices social responsibility (incorrectly) in the case of “doing well while doing good.”

Overall, the literature is divided on the exact consequences of investing in ethical mutual funds. For example, it has been shown that volatility in said market is lower than the volatility of conventional funds (Bollen 2007; Renneboog et al. 2005); but this does not include a discussion on the effects of reducing diversification. Investing in a closed universe is expected to limit the power of diversification and thus it can result in lower risk-adjusted returns. Yet consistent evidence of underperformance of SRIs has been missing.

Looking at the ethical aspect, traditional numerical indexes used to measure the performance of mutual funds do not take such features into consideration. Particularly, the Sharpe ratio (Sharpe 1966), the reward-to-half-variance index (Ang and Chua 1979), and the Treynor index (Treynor 1965) are computed as ratios between the expected excess return and a risk indicator without considering additional features (Basso and Funari 2003). Still, Goldreyer and Diltz (1999), compute Sharpe and Treynor ratios to show that social screening does not affect the investment performance of ethical mutual funds in any systematic way. Furthermore, Statman (2000) shows that the DSI indexFootnote 16 (which is one of the most well-known SRI indexes) has a higher Sharpe ratio than the S&P 500, which implies that investors seeking to optimize the mean-variance would prefer the ethical investment.

Believers in the efficient market hypothesis argue that it is impossible that SRI funds outperform their conventional peers (Renneboog et al. 2008). At most, prior research has found that socially responsible investing performs at least as good as traditional investment portfolios.

Hamilton and Statman (1993) and Statman (2000) use a sample of SRI funds and non-SRI funds for the periods 1981–1990 and 1990–1998, respectively, to estimate Jensen’s alphas based on CAPM, using the DSI 400 index and the S&P500 index as the benchmark returns for SRI and non-SRI. In the end, the authors find no statistical difference between the Jensen’s alphas, thus favoring the first hypothesis. These results are consistent with Diltz (1995), Guerard (1997) and Sauer (1997).

Later attempts included the use of Fama and French’s three factor model as well as the inclusion of Carhart’s momentum factor. Bauer et al. (2005) find no statistical difference in the performance of SRIs for the overall period 1990–2001, but they do find a “catching up” period in their early life. Their results are consistent with Renneboog, et al. (2008a) who reiterates the study for the period 1991–2003. Renneboog, et al. (2008a) also find said catching up period in the sub-sample 1991–1995. Surprisingly, though, the authors also find that ethical funds outperform their counterparts for the sub-period 2001–2003 (though it is not statistically significant).

Still using Carhart’s four factor model, Gil-Bazo et al. (2010) compare the pre and after fees performance of ethical funds against non-ethical funds for the period 1997–2005. They find that ethical funds have better before and after fees performance when compared to non-ethical funds of the same characteristics.

Most of the literature, however, focuses on the social factor of ethical funds and how SRIs outperform conventional investing due to that factor. Yet, several authors (Kurtz and DiBartolomeo 1996; Guerard 1997; Kurtz 1997 report that the reason for the over performance of the DSI 400 is due to the large investing on growth stocks and not the social factor.

Geczy et al. (2005) show that investing only in ethical funds carried a significant financial cost for the period 1963–2001. Yet on the other hand, Bollen (2007) justifies the profitability of SRI given that investors see beyond the traditional risk-reward optimization problem, as they may possess a multi-attribute utility function which incorporates a set of personal and societal values.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rubio, J.F., Maroney, N. & Hassan, M.K. Can Efficiency of Returns Be Considered as a Pricing Factor?. Comput Econ 52, 25–54 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10614-017-9647-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10614-017-9647-y