Abstract

Joanne Belknap’s recent ASC presidential address included a critique of Convict Criminology’s activism. A number of concerns were provided, although of particular importance here are, first, Belknap’s concerns regarding the absence of ‘marginalized voices’ in the Convict Criminology network. Second, the issue of defining how non-con academics function as Convict Criminology group members. This paper responds to these criticisms. Specifically, we discuss the question of ‘representation’ in BCC and our attempts to remedy this issue. We also draw attention to the academic activism that British Convict Criminology is conducting in Europe. This includes a detailed discussion of the collaborative research-activist activities that involve non-con as well as ex-con academic network members. We demonstrate how these collaborations explain the vital group membership role that non-con academics assume in the activism of Convict Criminology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since Convict Criminology’s (CC) emergence in the 1990’s it has been the subject of some criticism and debate. The most significant criticisms have included concerns around epistemological integrity and/or methodological robustness, and the limited representation of marginalized cohorts, i.e. ethnic minorities and women. A few critics have even questioned whether CC is a distinct criminological perspective within the discipline (see Lilly et al. 2011; Larsen and Piché 2012; Newbold and Ross 2012).

More recently, Joanne Belknap, in her ASC presidential address (2014) echoed some of these concerns, and added to them questioning both critical criminology’s and Convict Criminology’s role in, as she articulates, ‘criminology activism’. She also criticized CC for being predominantly white and male in constitution. Specifically, she argued (as have others e.g. Larsen and Piché 2012) that the network suffered in terms of a ‘race and gender gap’; missing from the network are the scholarly voices of other marginalized cohorts who have ‘served time’. These include the voices of women, ‘people of color’ and LGBTQ scholars. Belknap further voiced a concern regarding the inclusion of non-con academic network ‘members’ under the label convict criminologist. Specifically, and drawing on Earle’s (2014) work, she stated that she was reluctant ‘to define those who have not served time as convict criminologists’ (Belknap 2015: 8).

The extents to which these claims are warranted are debatable and our CC colleagues are addressing many of the issues raised by Belknap in this special edition of Critical Criminology. Whilst we, the authors, will also be addressing some of the issues raised and assessing the validity of these claims, we will be contextualizing our response to these criticisms in our experiences, observations and work, as leading members of British Convict Criminology (BCC), a CC network recently developed in the UK, with very strong connections to the US CC network. Given BCC’s growing significance and contribution to both criminology and the wider criminal justice arena, as outlined below, we believe our contribution is important. Therefore, this paper responds to these criticisms by drawing attention to the academic activism that BCC is conducting in the UK and our attempts to do so in Europe. It also addresses the issue of non-con academic ‘members’ and how they function as CC group members. As well as considering Belknap’s concerns regarding the absence of ‘marginalized voices’.

The Emergence of British Convict Criminology

In brief, British Convict Criminology (BCC) was formerly established in January 2012 with the core steering group consisting of Andy Aresti, Sacha Darke and Rod Earle. Since its inception it has steadily grown in numbers, currently peaking at around 100 ‘members’. We use the term ‘members’ loosely here as, importantly, like its North American counterpart, BCC has no formal constitution or membership, but has developed a constituency of interest and support among prisoners, prison workers, former prisoner academics (ex-cons) and conventional academic criminologists (Ross et al. 2014). All we ask of those that consider themselves to be members of BCC is that they self-identify as falling into one of four categories: prisoners or ex-cons studying in higher education (in criminology or cognate disciplines such as sociology, psychology, politics or law); academics involved in BCCs academic mentoring scheme for prisoner members or in a higher education program the authors are running at HMP Pentonville prison (in which we take a group of University of Westminster criminology students to study with prisoners); ex-con academics researching on prisons, and other academic prison researchers that take a convict criminology perspective, that is, research in collaboration with educated prisoners or former prisoners. (For detail of BCCs academic mentoring scheme and higher education prison program, see Darke and Aresti 2016; for detail of collaborative writing between prisoner, ex-con and non-con BCC members, see Aresti et al. 2016). Whilst this interest and support primarily stems from the UK, we are beginning to forge links with academics in mainland Europe, principally Norway and Italy.

Given this and the significant strides BCC has made since its inception, in terms of developing the CC perspective, evident in our growing membership, our consistent representation and ‘voice’ at major conferences in the UK and Europe, our growing publication list and engagement in various forms of activist work (see Aresti et al. 2016; Darke and Aresti 2016; Ross et al. 2014 for an overview) we feel we are well placed to respond to some of the issues raised by Belknap. In fact we believe it is critical that we do so for two reasons: first because there was little acknowledgment of the important contributions BBC has made to criminology here in the UK, other than a brief mention of Earle’s (2014) work in a footnote; and second, although we are part of the wider CC network, and share the same underlying philosophy and critical orientation there are some significant differences between the US and UK in terms of criminal justice and academic criminology (Ross et al. 2014: 124). These include significant differences in prison population, and in some instances differences in approaches to dealing with criminal justice issues, penal policy and resettlement/corrections strategies. Consequently, this has a variety of implications for BCC network ‘membership’, ‘criminology activism’ and our mentoring and research, amongst other things.

Despite these differences, as mentioned we have strong ties to the US network and a growing presence in British criminology, and yet BCC was not acknowledged in Belknap’s address. Belknap’s criticisms appeared to be exclusive to the US CC network, with little consideration of the contributions made by other convict criminologists outside of the US. Arguably, this is because as recently highlighted by Ross et al. (2014) CC has remained largely a North American movement. And whilst CC’s profile is developing internationally, it is still in its infancy and therefore any discussion or criticisms of CC or their work appear to be primarily, if not exclusively US focused. Although difficult to verify, we imagine that few US criminologists outside of the CC network are aware of BCC. This is problematic and has a variety of implications for the development and internationalization of CC. As we have previously written:

One of the important challenges facing CC involves moving beyond its North American roots. CC has remained mostly a North American initiative, concerned primarily with correction-related issues relevant to that region and shaped by the exceptional carceral conditions applying to the United States

(Ross et al. 2014: 122).

Despite the (perceived) lack of awareness of BCC outside of the UK, and in particular American mainstream criminology, it has a growing presence in British Criminology, as previously illustrated. And despite the challenges we face bringing CC to Europe we are developing links with both ex-con and non-con criminologists here in the UK and mainland Europe. Moreover, we have forged strong links with non-governmental organizations—NGO’s (voluntary sector/third sector organizations and activist groups) here in the UK, and are beginning to do so in other countries e.g. Norway and Italy (see Ross et al. 2014).

The BCC Network and the Absence of ‘Marginalized Voices’

An important criticism put forward by Belknap concerned the lack of, or absence of ‘men of colour’, women and LGBTQ scholars in the CC network. Whilst to some extent this is a valid claim with respect to BCC, this needs to be considered within the broader social context. Like in the US, this lack of representation is arguably a function of wider social and structural constraints which serve to reproduce inequality within a variety of spheres (e.g. employment, housing, education, welfare services etc.) including the academy. As Belknap rightly argued, the absence of these marginalized cohorts was (and to some extent this is still the case) manifest in the academy, which up until recently ‘has been dominated by White men who have likely disproportionately come from class-privileged backgrounds’ (p. 6). Moreover, the criminalization and incarceration of these marginalized cohorts, especially people from ethnic minorities and women, serves to reinforce this inequality and create deeper divisions (see Jacobson et al. 2010; Malloch and McIvor 2011) limiting their access to university, as well as other arenas that encourage and provide opportunities for social mobility. Mirroring Belknap’s example of her rejected doctoral student, we, the authors, are aware of a few cases where incarcerated or formerly incarcerated individuals, with strong academic profiles have been refused entry to the academy. Interestingly, these cases have transcended the ‘boundaries’ of gender and class, although to our knowledge, not race or sexuality.

On a more local level there are a number of possible reasons as to why this absence exists in the BCC network. As we have explained elsewhere, the UK has a significantly smaller prison population in comparison to the US. The UK prison population currently stands at around 86,000 (MOJ 2015), which is only a fraction of the 2.2 million boasted by the US (ICPS 2015). Consequently, fewer people will have made the transition from prison to university, and of course this has obvious implications for the BCC network in terms of membership (Ross et al. 2014). Amplifying this problem are current budget cuts within the CJS, and more specifically steep increases in higher education fees in 2012, alongside a barring of prisoners applying for student loans until they are within 6 years of their first potential date of release.

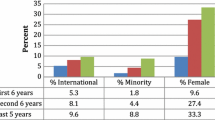

Despite this, the BCC network is growing, and importantly still ‘recruiting’ and mentoring prisoners who are engaged in higher education or post graduate study. As noted, the network is currently peaking at approximately 100 ‘members’. Like our US cousins, the network consists of a mixture of ex-con and non-con academics, and has a healthy balance in terms of gender. However, as highlighted by Belknap there is an absence (in the BCC network) of both female and LGBTQ scholars who have served time. We put this down to three primary reasons. First, BCC is relatively new and is still establishing itself in British (and European) criminology, and whilst we do have a presence in the academy, this has probably not filtered down to the grassroots (students/university), where we are more likely to find potential candidates. Second, given the significant difference between the male and female prison populations in the UK—there are currently around 81,000 males in prison compared to 3900 females (MOJ 2015; PRT 2015)—it is difficult to contest that recruiting women prisoners’ or former prisoners that fit the credentials will be no easy task. Although we know of two potential candidates, one we have recently met with. Both have expressed interest in CC, and are considering joining BCC. We have some leads for other potential candidates and another member of the network is following these up.

In terms of members from BME (Black and Minority Ethnic) communities, we have a few male members that have served time and come from a BME background; at least two are black males. Although these members do not have Ph.D.’s they are working towards them, currently doing Master’s degrees in criminology. And whilst arguably this is not ideal when considering that BME communities are significantly overrepresented in the British penal system (Jacobson et al. 2010; MOJ 2015; PRT 2015; Webster 2007) it is a step in the right direction. As for LGBTQ scholars there might well be a number of network members that identify as being part of this community, although at present we know of just two. Many of our network members are only known to us via correspondence, and not known on a personal level.

Nevertheless, we do agree the absence or underrepresentation of these marginalized cohorts is an issue and something we endeavor to change. We are devising a strategy that will assist us in identifying and ‘recruiting’ potential candidates. As we are increasingly being invited to present/give talks on CC at universities around the country we hope to increase our membership generally, but especially in terms of these ‘missing voices’. Although it should also be noted that despite ‘informal invites’ to ideal candidates, like in the US, in the odd instance people have been reluctant to join the network (Ross et al. 2014)

Before moving on from the issue of ‘absent voices’, we would like to raise a related and equally important issue that was not considered by Belknap (or others e.g. Larsen and Piché 2012) when discussing the ‘race and gender gap’ in CC. When highlighting the issue of ‘absent voices’, she failed to recognize or acknowledge the issue of social class when criticizing the CC network. To our knowledge, apart from comments made by Alan Mobley, (a US convict criminologist) little has been said on the matter. Mobley (2010) comments on social class briefly, stating that the CC group is mostly of European American extraction and middle class. He goes on to make the distinction between the experiences of the ‘middle class’ prisoner and the ‘typical’ prisoner, i.e. the disadvantaged and marginalized, as articulated below:

Although the large majority of people swept into prisons by the wars on drugs and crime have been minority, poor, and poorly educated, another subgroup has been brought along, mostly for the ride, it seems. This group, mostly of European American extraction and middle class, found itself imported into a world of strange customs and moral codes. The prison experience itself, far from being routine and an accepted rite of passage, was bizarre. Some individuals within this group began to look upon the prison as an object of study and brought the culture of prison into their inquiry as well. They have become known, at least in their initial foray into research and publishing, as convict criminologists (Mobley 2010: 335).

Given this, it is important to highlight that social class when mentioned by Belknap was only considered briefly and implicitly in the context of other marginalized identities, i.e. gender, race (non-white), sexuality etc. This is an omission that is common in the first author’s (AA) experience of ‘working in the criminal justice field’ and academia. This omission is particularly problematic in the current context, as there is an inherent assumption that white middle class convict criminologists will experience the world and share the same world view as their working/lower class counterparts. Yet as Mobley (2010) rightly points out, experiences of prison can be quite different when viewed through the lens of social class, as is the case for other contextual factors (e.g. gender, ethnicity, type of prison, regimes etc.) which also play a significant role in shaping the lived reality of the prisoner (Earle 2014; Newbold and Ross 2012). Arguably, class is as equally as important as these contextual factors, and those identified by Belknap (see Aresti et al. 2016 for a discussion of class issues).

Whilst we do not want to lose ourselves in the relativist argument that everyone experiences prison in a completely different way (something we discuss later), we are keen to include in Belknap’s ‘underrepresented voice’ argument, the lack of the lower/working class voice in criminology. Especially when considering, like BME communities, the lower/working classes are significantly overrepresented in the prison population (MOJ 2010; Social Exclusion Unit, 2002). Yet arguably, severely underrepresented (in senior positions), in the statutory and non-statutory services working in the criminal justice system. This speaks volumes in terms of knowledge production and power differentials, as we have previously argued (Aresti et al. 2016). Maybe the class thing is not an issue in the US CC network, but it has been the cause of some tension in our network.

‘Criminology Activism’

Belknap also voiced her concerns regarding academic criminology and its lack of involvement in activism, stating:

I am concerned that academic training and university climates frequently work against our commitment to advancing social and legal justice changes, what I refer to as criminology activism (Belknap 2015: 1).

Whilst this might be the case in the US, this is not necessarily the case over here in the UK, especially where BCC is concerned. Both ex-con and non-con network members are directly involved in ‘criminology activism’, in its various forms, through their strong links to VSO’s, NGO’s and/or campaign groups. These third sector organizations (TSO’s) have a history of delivering criminal justice services and campaigning for policy change and penal reform. Third sector involvement in criminal justice issues is increasing, with policy agendas shifting towards a mixed economy of service provision partnerships, with services provided by statutory, private and TSO’s (Meek et al. 2010). This has a variety of implications for the ‘prisoner’.

The growing presence of TSO’s and particularly voluntary sector organizations/charities in the criminal justice arena has benefited some of our ex-con members. Some of these individuals have long histories with some of these organizations. They were supported or assisted by them in various ways in the early days when incarcerated or post-prison, when trying to resettle back into ‘conventional life’. This has led to a fruitful relationship whereby now we are actively invited to take part in campaigns or contribute through talks, presentations, symposiums etc. Some of the strongest links BCC has to these TSO’s are with the following organizations: UNLOCK, the Prisoners Education Trust (PET), Open Book, the Prison Reform Trust (PRT), and the Howard League for Criminal Justice.

Personally speaking, the first named author (AA) has been involved with all of these organizations in different ways, be it campaigning, researching for policy change, advocacy/consultancy work etc. Other ex-con members of BCC are currently involved with at least one of these organizations, or have been in the past. Here they have assisted the organization in trying to implement change in the criminal justice system, be it penal reform, resettlement/rehabilitation policy or campaigning against discriminatory practices applied to ‘prisoners’.

Directly verifiable examples of this include AA’s position as chair of the trustee board (until recently) for UNLOCK, an organisation that assists people to overcome the stigma of their previous convictions. They also are heavily involved in policy and campaign work that challenges discriminatory practices and promotes socially just alternatives (see www.unlock.org.uk). Another example is AA’s advocacy work with the Howard League, a penal reform charity, where he has assisted in their campaign for implementing changes within the criminal justice system (www.howardleague.org.uk). And more specific to education, his involvement with the PET, and their work on education and prisons (see www.prisonerseducation.org.uk/events/academic-symposium). Other examples include research based reports with VSO’s, for example the PRT, a penal reform charity which attempts to effect change in prisons and resettlement policy (for example, see Edgar et al. 2012).

Similarly, many of our non-con members are involved in prison activism. For instance, the second named author (SD) sits on the steering committee of the Reclaim Justice Network (see downsizingcriminaljustice.wordpress.com), a collaboration of VSOs, academics and people directly affected by the penal system (e.g. ex-cons and the families of current prisoners), which campaigns to radically reduce criminal justice responses to crime and build effective and socially just alternatives. With AA, SD is also developing research activist links with the Norwegian Association for Penal Reform (KROM) (see www.facebook.com/Kriminalreform; Mathiesen 2015) and, in Italy, Ristretti Orizzonti (see www.ristretti.org), both prison abolitionist, research activist organization that similar to CC are made up of collaborative partnerships between prisoners, ex-con and non-con academics. Other recent collaborative non-con/ex-con BCC prison activist activity includes (in 2014) facilitating ex-con focus group discussions at a joint academic/VSO event, A Civic Conversation: Critically Discussing Experiences of Northern Ireland’s Criminal Justice System, (2015–2016) consultation by the Ministry of Justice in its Review of Education in Prisons, and an evaluation of a community chaplaincy mentoring scheme at a local prison, which is planned for 2016, but is currently on hold while AA is appealing against a decision not to grant him access.

How Do Non-con Academics Function as CC Members?

As noted, critical to CC is the notion that the ‘insider perspective’ or ‘convict perspective’ is the starting point for both knowledge production and empirical inquiry (Richards and Ross 2001; Ross and Richards 2003). Whilst CC is predominantly led by a number of ex-convict academics that have an intimate knowledge of the penal system, it is a collaborative venture, with the CC network comprising of prisoners, ex-con and non-con academics, sharing the same philosophy and critical perspective. Given that the ex-con academics have had first-hand experience of the penal system, they use their past experiences of the criminal justice system and present academic knowledge, to inform and critique current criminological perspectives, policy, research paradigms and research findings (Richards and Ross 2001; Ross and Richards 2003). This is a central tenet of the perspective.

As Larsen and Piché (2012: 199) have noted, Convict Criminologists integrate their direct experience as criminalized individuals into their criminological analysis, and this defining feature is what is argued to distinguish it from other critically orientated criminological perspectives. Yet this raises a contentious point. Given this emphasis on first-hand experience or the ‘insider perspective’ and the value afforded to taking this epistemological position, it raises the thorny issue of ‘what is the role and function of non-con academics in the CC network?’ And as argued by Belknap, can we even ‘define those who have not served time as convict criminologists?’ (Belknap 2015: 8). Given CC’s emphasis on first-hand experience, and ‘who can know or who can be the knower in criminology’ (Larsen and Piché 2012: 199) this certainly generates an epistemological tension.

For the current authors, however, non-con academics also contribute to the CC perspective. What ultimately binds our members is not so much the common experience of prison but a common desire for radical reform of prisons, and a common belief that insider perspectives have much to contribute to research activism. From the outset, BCC has been led by non-con as well as ex-con academics, including the second named author. Through their time spent working in prisons/with prisoners, as educators, academic mentors, practitioners or ethnographic researchers, and in the research-activist work they have developed with prisoners and former prisoners, our non-con members have an important role to play in developing insider perspectives. Importantly, this is not simply a case of non-con academics facilitating insider perspectives, that is, supporting the academic training/production of former prisoner academics, and then standing aside once their job is done. Our non-con members’ contribution is far more wide-reaching as argued below.

Drawing on Earle’s (2014) work, Belknap argues, as have others (see Newbold and Ross 2012) that spending time in prisons, either as a researcher or as a practitioner, does not give one the sense of what it is like to be incarcerated; a truism which we believe few if any of the non-con academic members of BCC would contest. However, as a result of their collaborative work with prisoners and former prisoners, many of the non-con members of the network have acquired in-depth understanding of the realities of prison life that can/should also be utilized in the development of the CC perspective. Several of our members also have a depth of experience of activism, some of which we have mentioned. In this sense, parallels can be drawn between the work of BCC and Norwegian KROM, which has successfully brought prisoners, former prisoners and non-con academics together on an equal footing for more almost 50 years (Mathiesen 2015). Naturally, a non-con academic cannot speak for someone about their prison experience. This is the starting point for CC. However, it does not mean that non-con academics cannot speak with someone that has experienced imprisonment. Our non-con members have a wealth of experience and understanding of prison and research activism that can only benefit the CC perspective, so long as it is utilized alongside rather than in place of the inside knowledge and perspectives of prisoners and former prisoners.

Given the ‘experiential insight’ of our non-con members we would argue that these ‘enlightened’ academics not only have a good understanding of prison life, but also a pronounced degree of empathy, not afforded to many other academics working in the field. For us, empathy in this instance or the ability to adopt an ‘insider perspective’ (Conrad 1987) is better conceptualized in terms of a continuum, rather than in terms of the ‘privileged’ ‘convict perspective’ versus ‘non-convict perspective’.

The issue with this dichotomy is that it generates binary opposites and creates an artificial boundary, an ex-con versus non-con dichotomy. We would argue that this is unhelpful as it not only undermines the valuable work conducted by ‘our’ non-con peers, but also discredits their equally valuable experiential insights and contribution. A more fruitful question to ask in this respect, and a stance taken in phenomenological research, ‘is to what extent can one ‘stand in [the ‘prisoners’] shoes’ (Smith et al. 2009: 36). Specifically, we would like to explore the degree to which a non-con CC member can access the ‘lived realities’ of prison. This is particularly important given the epistemological tension outlined above. A complimentary question could then be what factors determine the degree to which these non-con members can access the ‘prisoner’s lived experience’.

During our brief existence, the non-con members have contributed to the development of the BCC network in a variety of ways. As highlighted earlier the non-con members have been pivotal to the development of the group, and without their contribution, in our view, BCC would not have developed to the extent that it has, if at all. Similarly, in the US, the significant contribution these members have made in terms of the development of this perspective has been well articulated as exemplified below;

Some of the most important members of our growing group are prominent critical criminologists; although not ex-cons, they have contributed to the content and context of our new school. This expanding pool of talent, with its remarkable insights and resources, is the foundation of our effort (Richards and Ross 2001: 181).

Yet, whilst acknowledging the important contribution made by our non-con peers, the CC network, has neglected to provide, to our knowledge, a detailed discussion/response of/to the epistemological tension generated by the perceived ex-convict versus non-convict dichotomy. This has left the movement open to criticisms such as Belknap’s, which in-effect questions the role and identity of our non-con membership. Our aim is to address this issue by providing a conceptual argument, which we hope will attenuate this epistemological tension.

Whilst Belknap’s critique is brief in this instance it is a very significant point. Given the nature of the group, its philosophical underpinnings and epistemological orientation; it is understandable why critics may question the identity and role of the non-con group members. How can someone claim to be a Convict Criminologist if they have not ‘served time’? Especially when considering that the cornerstone of this perspective is that knowledge production is theoretically and empirically informed by ex-con academics that have intimate knowledge of the penal system (Richards and Ross 2001). On first sight, the inclusion of non-con academics in the network appears to be somewhat contradictory.

Yet this contradiction and debate is not exclusive to CC, as it has occurred elsewhere, for example, within the realms of feminism. The question ‘Can Men be Feminists’? has been posed and debated (Crowe 2011a), as has the notion that ex-con academics in the CC network produce work that is more valuable than that of their non-con peers (Newbold and Ross 2012). The implications here are that ex-con members of CC are in a unique and ‘privileged’ position and to some extent they are. Utilizing Crowe’s (2011a, b) work on feminism as a frame of reference here, it could be argued that non-con group members might well subscribe to CC’s philosophy and sentiments, just as some men might adhere to feminist ideals in theory, but can they really place themselves in the ‘prisoners shoes’ or view the world through the ‘eyes of a women’?

As Crowe (2011a: 2) comments in his provocative work;

Feminism is about women; that is, it centres on recognizing and promoting women’s interests and perspectives. The feminist outlook, then is premised on knowledge and understandings of women’s experiences—put simply, these are experiences men cannot have

Intuitively, this argument holds well for feminism, although of course this view has been challenged by others who believe men are critical to the feminist movement, and their membership is necessary (Crowe 2011a, b). Yet when considering this debate in the context of CC it appears to hold less gravitas. It would be hard to defend the view that the ex-con versus non-con dilemma in CC is on an equal footing to, and as complex as the feminist issue regarding men identifying as feminist. For us, the distinction between ex-con and non-con members is less complex than the traditional gender dichotomy. Gender is woven into the fabric of one’s being in the very early stages of child development, via a complex interaction of genetic, biological, developmental, psychological and environmental/social factors (Martin and Ruble 2009). Typically, gender identity is a core component of our sense of self, shaping the way we experience the world, and is enmeshed in a variety of other identities and contexts. However, gender identity is also subject to variability, and there is much overlap between women and men on a range of psychological variables, behaviors and other characteristics (for an overview, see Hyde 2014; Martin and Ruble 2009; Stewart and McDermott 2004).

Given this, it would be difficult to argue that first; the ‘prisoner’ identity is as equally as complex and consuming and/or pronounced as one’s gender identity, and therefore access to the lived realities of prison might arguably be easier in comparison. Although of course, we do acknowledge that when serving time, and especially when doing an exceptionally long sentence, the ‘prisoner’ identity is, or can be an all-consuming part of one’s existence, as identified by numerous authors (e.g. Irwin 1970; Irwin and Owen 2005; Liebling and Maruna 2005; Ross and Richards 2003; Sykes 1958). Second, given that the ‘essentialist’ gender dichotomy, female versus male, is also problematic, and that these categories are argued to be less fixed and stable, with demarcations being less sharp (Hyde 2014; Martin and Ruble 2009; Stewart and McDermott 2004), we argue that it might be useful to apply this conceptual frame to the ex-con versus non-con dilemma. That is, it is more constructive to focus less on the differences between ex-con and non-con members, and rather focus on the issue of, to what degree our non-con peers can access the lived realities of prisoners’. Therefore, taking this less essentialist approach, we see the ex-con versus non-con dichotomy as problematic and argue that we should view experience, and the degree to which one can access it, on a continuum. Especially as we believe that the ex-con versus non-con dichotomy creates artificial boundaries, whereby one individual, ‘the insider’ is typically privileged, in that they are closer to the experience than those that have not lived through it.

On the surface, this point leaves little room for debate. It assumes that experience is an uncomplicated event that is directly accessible and easily understood. Yet experiences are taken for granted, and are rife with complexity, as Smith et al. (2009: 33) articulate;

Experience itself is tantalizing and elusive. In a sense pure experience is never accessible; we witness it after an event…[as] the person is a sense-making creature, the meaning which is bestowed by the [individual] on experience, as it becomes an experience, can be said to represent the experience itself.

Clearly, ‘experience’ is temporal in nature and realized, not in its immediate manifestation, but only reflectively after the event, or as Van Manen puts it, in ‘past presence’ (2006: 36). Moreover, our access to and understanding of the experience is also subject to linguistic constraints, as we realize experience through language, and specifically our linguistic resources (Smith et al. 2009). Therefore, arguably even the privileged ‘insider’ or ‘knower’ can never grasp the full richness of the experience. Given that a ‘lived experience’ is not fully accessible in its entirety, an alternative way of conceptualizing the non-con versus ex-con dilemma is to conceptualize experience as being on a continuum: asking the question ‘how close can one get to another’s ‘lived experience’ or to what extent can ‘you put yourself in someone else’s shoes’.

If we consider access to the ‘prisoners’ experience in this way, there is no real need to have such sharp demarcations within the CC network i.e. an ex-con versus non-con dichotomy. And whilst we would like to stress that we do not mean to undervalue the ‘prisoners’ experience, as the scars remain with many of us to this day, we see this as a fruitful alternative. It also enables us to consider a related issue that is also a point of contention.

Some authors have suggested that the ‘privileged knowledge’ approach, or the view that prison experience alone, makes you an authority on prison is problematic because it is ‘no substitute’ for robust empirical enquiry (Newbold and Ross 2012). It is also misleading as prisoners are a heterogeneous group, experiencing prison in their own unique way in many respects. The ‘privileged knowledge’ position has been criticized in this instance, because it is argued that ‘prisoners’ experience of incarceration is qualitatively different, as a result of a range of personal, situational, contextual and structural factors (Earle 2014; Newbold and Ross 2012). And whilst we certainly agree with these authors, that is, that prisoners manifest with diverse experiences of incarceration, we also believe that on a basic level there is a shared, homogenous experience of prison. An essential quality or ‘essence’ that is unique to the ‘prisoners’ experience, and defines that experience, or in Husserlian terms, universal invariant phenomenological structures that constitute the (prisoners) experience (Husserl 1913/1982). Reinforcing this, on an existential level, Heidegger (1931/1962) makes the distinction between the ontic and ontological aspects of existence; the former refers to universal ‘givens’ or structures of being; the later refers to the unique and particular means, that is the subjective nature, by which any universal given is expressed. In this respect, one’s existence in prison is shaped to a certain extent by the structural constraints and restrictive nature of prison. Typically, loss of freedom, loss of agency, loss of connection to others are commonly experienced by ‘prisoners’, regardless of their unique subjective experiences (Irwin and Owen 2005; Sykes 1958) although of course there might be some exceptions.

So to recount our argument so far, we have argued that the ex-con versus non-con dichotomy is problematic and exclusionary, and that it is more fruitful to conceptualize experience, or more specifically ‘access to one’s experience’ be it your own, or someone else’s, on a continuum, and as a matter of degree. By doing so, we believe we can overcome the epistemological tensions generated by the ex-con versus non-con dichotomy. Using this framework, we argue that non-con members of the CC network can to varying degrees (depending on their experiential insight) access the ‘lived reality’ of prison and appreciate what it is like ‘doing time’. We reinforce this with our view that there is an essential quality or ‘essence’ that is unique to the experience of being a prisoner, regardless of individual variations and the idea that prison is to some degree a uniquely subjective experience.

Earle (2014) argues that ‘spending time’ in prison is quite different to ‘serving time’, and that it does not give you a sense of what prison is like. And whilst we agree with this, we also believe that this reinforces the ex-con versus non-con dichotomy, and question the sharp distinction between the two. The dichotomy is too simplistic and like the ‘essentialist’ gender categories discussed earlier, it does not account for variations or ‘overlaps’ in experience. Again, this is not to discredit the value of the ‘prisoners’ experience, just a means of balancing the scales and illustrating the inherent conceptual issues in the ex-con versus non-con dichotomy.

The first thing to consider is the notion of ‘spending time’ in prison. Some of our non-con members are established academics who have spent a significant amount of time in prison, either as practitioners, educators or researchers. Arguably, this has given them a ‘flavor’ of prison life, and a pronounced understanding of prison culture and the ‘realities’ of prison, in particular the ‘essences’ or invariant experiential structures (Husserl 1913/1982) we spoke of earlier, constituting the prison experience.

Of course, this is not the same as having a ‘sense’ of incarceration, although it raises a provocative question regarding temporality and time served. How much time served is necessary to gain a ‘sense’ of what prison is really like? For instance, when AA was in prison nearly two decades ago, on occasion he shared a cell with prisoners who were doing very short sentences. One of his cellmates served 2 weeks, another 1 week. We wonder to what extent these men got a ‘sense’ of what prison is like in this time? They undoubtedly had some experience of those invariant experiential structures discussed earlier i.e. loss of freedom, disconnection from the outside world, loss of agency etc. (Irwin and Owen 2005; Sykes 1958). Yet a week or two in prison whilst potentially traumatic and damaging hardly qualifies one for having an intimate knowledge of the penal system. So how much time served is necessary to qualify someone as having an intimate knowledge of the penal system?

Intuitively, we believe many of the non-con academics in BCC could provide more insight into the ‘lived realities’ of prison life, than AA’s two cellmates. So given this, and considering Belknap’s reluctance to define someone that has not served time as a Convict Criminologist, we wonder how we would define these men, AA’s cellmates, if indeed they manifested with the other credentials required for ‘membership’ of the CC network? Any imposition of a time-frame or demarcation criteria (cut off point for time served) would be arbitrary, as it would be difficult to determine what length of time denotes quality time served.

Developing this conceptual argument, and further problematizing the ex-con versus non-dichotomy, we wonder where ‘prisoners’ partners or ‘significant others’ fit into the equation. A significant other is an individual who has been deeply influential in one’s life and whom one is emotionally invested. This can be a partner, family member or others outside the family (Anderson and Chen 2002). Many of the psychological harms and emotional traumas prisoners experience, are also experienced by loved ones; experiences of loss, isolation, hopelessness, deterioration in the relationship, stigmatization and victimization (Arditti 2001, 2005; Arditti et al. 2003; Murray 2005). Relative to this, ‘significant others’ are also subjected to the same negative and adverse treatment prisoners experience in some instances when visiting their loved ones, including hostile staff attitudes, aversive searching practices, poor visiting facilities and poor treatment by prison staff when visiting loved ones (ibid).

Considering this, we argue that ‘significant others’ are well positioned to speak about the ‘realities of prison’ as their lives, experiences and existence are also shaped by their loved ones confinement in many instances (Arditti 2005; Arditti et al. 2003; Murray 2005). For many, these experiences constitute a shared reality, a reality encountered by the self and significant other. The self is a relational being and is enmeshed with and shaped in parts by its connection to significant others. One’s sense of self, including thoughts, feelings, motives and other characteristics can be, and are influenced by this relational engagement with significant others (Anderson and Chen; 2002; Chen et al. 2006; Finlay 2009).

Inevitably, there will be exceptions here, and of course when considering significant others, we need to acknowledge that this is by far a homogenous group. There is much experiential variation as a result of cultural, contextual and situational factors (Murray 2005). However, this aside, as we have argued, we believe that significant others are well placed to talk about the realities of prison, and in some instances they might even get close to a ‘sense of what prison is like’. AA will use his own prison experience to support this argument, and use his partner as a case study, to illustrate how someone that has not served a prison sentence can indeed have a ‘grip’ on the realities of prison.

A ‘Significant Other’s’ Experience of Prison

My wife (AO) and I wrote to each other nearly every day for the first year or so, when I was in prison serving a 3 year sentence (I ended up doing a year and a half inside). We still have the letters. One day we will go through them and revisit our shared experience of ‘doing time together’ on different sides of the wall: a few hundred letters capturing the ‘lived realities’ of prison; our written conversations detailing what life was like for both of us at the time. Letters were so numerous simply because phone calls were limited to one a week in the early days of my sentence. Things did improve as the sentence went on. None of this trying to reflect on an experience that is nearly two decades old. The raw data is there, telling our story as it unfolded, the reality of our situation documented in ink.

There were significant events during our prison experience that still hold a strong resonance now. For starters, we got married in prison. We both remember the day vividly. How many ‘prisoners’ can say they got married in prison? Of course we are not the first, but relatively speaking, I imagine there is not that many people that have. However, the point is that AO and I know what that experience is like. And yes we undoubtedly experienced it in our own unique ways, although undeniably we shared that experience, we ‘lived it together’ and there is a mutual resonance that is unique to this experience. Few people can get a ‘sense’ of what this was like, regardless of their status as an ex-con or non-con.

Relative to this, AO, has also experienced many of the psychological and emotional harms outlined above, as a significant other; the degradation of being searched, the hostile staff attitudes, the painful visits that go to quickly etc. (Arditti 2001, 2005; Arditti et al. 2003; Murray 2005). She has also experienced the frustrations and difficulties unique to significant others, such as trying to negotiate prison visits i.e. unable to book a visit due to busy phone lines or travelling for hours to visit me further along in my sentence (Murray 2005). Arguably this is still part of the ‘prison’ experience, and something us ‘prisoners’ do not experience directly.

Given this, and AO’s academic/clinical credentials as a Systemic and Family Psychotherapist with a strong background in psychology. As a psychotherapist empathy and understanding of others experiences are critical to the role. She has conducted phenomenological research on female ‘prisoner’s experiences of desistance and for a spell she worked in a women’s prison, HMP Holloway, in the mother and baby unit, as well as experiencing prison as a ‘significant other’. And whilst she has not actually served time, when considering the above, critics would be hard pushed to deny the degree to which she understands or can empathize with the realities of ‘prison’. As Finlay (2009: 6) notes;

Our corporeal commonality and capacity for inter-subjectivity create the possibility of empathy and understanding of the other, in other words our embodied intersubjective horizon of experience allows us access to the experiences of others.

So the question we pose is: when using the ex-con versus non-con dichotomy as a model to distinguish between ‘privileged knower’ where we would place AO and where would we place AA’s cell mates who between them served 21 days in prison in total? In comparison who has more of a ‘sense’ of the realities of prison, AO or AA’s cellmates? We believe it would be problematic to define both AO and AA’s cellmates as ‘convict criminologists’, if indeed they met the other criteria required for membership of the network. Therefore clearly, the ex-con versus non-dichotomy is problematic, and generates un-necessary and un-useful epistemological tensions. However, as a conceptual frame for understanding the lived realities of prison our notion of a continuum (experience and the degree to which one can access it is on a continuum) is a much more useful way of approaching the issue, and overcomes the inherent epistemological tensions outlined above, in the ex-con versus non-con dichotomy.

Conclusion

Joanne Belknap’s recent ASC presidential address included a critique of Convict Criminology’s activism and concerns regarding the absence of scholarly voices, in the network, from marginalized communities/cohorts. We have responded to these critiques by providing details of the collaborative research-activist activities BCC is currently involved in. Moreover, we have discussed the ‘absence’ of ‘marginalized voices’ within the BCC network and have identified the inherent problems experienced when trying to recruit from these communities/cohorts. Of equal importance here, we have engaged with the issue of defining how non-con academics function as Convict Criminology group members. We demonstrate how these collaborations explain the vital group membership role that non-con academics assume in Convict Criminology. Complementing this, we also provide a conceptual framework, that we believe, overcomes the inherent epistemological tensions generated by the networks ex-convict versus non-convict membership. We argue that this dichotomy is unhelpful and provide an alternative way of understanding network membership. In doing this, our aim is to shift the focus of attention on to more important issues, namely, the pursuit of social justice, over inequality. Something that we believe is more likely to be achieved through not only the collaborative work of ex-con and non-con Convict criminologists, but also collaborative endeavors with other ‘critically minded’ groups or organizations.

References

Anderson, S. M., & Chen, S. (2002). The relational self: An interpersonal social-cognitive theory. Psychological Review, 109(4), 619–645.

Arditti, J. A. (2001). Introduction: Criminal justice and families. Marriage and Family Review, 32(3/4), 3–10.

Arditti, J. A. (2005). Families and incarceration: An ecological approach. Families in Society, 86(2), 251–260.

Arditti, J. A., Lambert-Schute, J., & Joest, K. (2003). Saturday morning at the jail: Implications of incarceration for families and children. Family Relations, 52, 195–204.

Aresti, A., Darke, S., & Manlow, D. (2016). ‘Bridging the gap’: Giving public voice to prisoners and former prisoners through research activism. Prison Service Journal, 224, 3–13.

Belknap, J. (2015). The 2014 American Society of Criminology Presidential Address. Activist criminology: Criminologists’ responsibility to advocate for social and legal justice. Criminology, 53(1), 1–22.

Chen, S., Boucher, H. C., & Tapais, M. P. (2006). The relational self revealed: Integrative conceptualisation and implications for interpersonal life. Psychological Bulletin, 132(2), 151–179.

Conrad, P. (1987). The experience of illness: Recent and new directions. Research in the Sociology of Health Care, 6, 1–31.

Crowe, J. (2011a). Can men be feminists? Adapted from Men and feminism: Some challenges and a partial response, 1–7. Social Alternatives, 30(1), 49–53. https://www.wlsq.org.au/assets/Uploads/Can-Men-be-Feminists.pdf. Accessed December 23, 2015.

Crowe, J. (2011b). Men and feminism: Some challenges and a partial response. Social Alternatives, 30(1), 49–53.

Darke, S., & Aresti, A. (2016). Connecting prisons and universities through higher education. Prison Service Journal, 225, 26–32.

Earle, R. (2014). Insider and Out: Reflections on a prison experience and research experience. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(5), 429–438.

Edgar, K., Aresti, A., & Cornish, N. (2012). Out for good: Taking responsibility for resettlement. London: Prison Reform Trust.

Finlay, L. (2009). Ambiguous encounters: A relational approach to phenomenological research. The Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 9(1), 1–17.

Heidegger, M. (1931/1962). Being and time (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). Oxford: Blackwell.

Husserl, E. (1913/1982). Ideas pertaining to a pure phenomenology and to a phenomenological philosophy: General introduction to a pure phenomenology (F. Kersten, Trans.) The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Hyde, J. S. (2014). Gender similarities and differences. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 373–398.

International Centre for Prison Studies. (2015). World prison brief: US prison population. http://www.prisonstudies.org/highest-to-lowest/prison-population-total?field_region_taxonomy_tid=22&=Apply. Accessed January 5, 2016.

Irwin, J. (1970). The Felon. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Irwin, J., & Owen, B. (2005). Harm and the contemporary prison. In A. Liebling & S. Maruna (Eds.), The effects of imprisonment. Willan: Cullompton.

Jacobson, J., Phillips, C., & Edgar, K. (2010). ‘Double trouble’? Black, Asian & minority ethnic offenders’ experiences of resettlement. London: Clinks.

Larsen, M., & Piché, J. (2012). A challenge from and a challenge to convict criminology. Journal of Prisoners on Prisons, 21(1 & 2), 199–202.

Liebling, A., & Maruna, S. (Eds.). (2005). The effects of imprisonment. Cullompton: Willan.

Lilly, J. R., Cullen, F. T., & Ball, R. A. (2011). Criminological theory: Context and consequences (pp. 226–229). London: Sage.

Malloch, M., & McIvor, G. (2011). Women and community sentences. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 11(4), 325–344.

Martin, C. L., & Ruble, D. N. (2009). Patterns of gender development. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 353–381.

Mathiesen, T. (2015). The politics of abolition revisited. Abingdon: Routledge.

Meek, R., Gojkovic, D., &Mills, A. (2010). The role of the third sector in work with offenders: The perceptions of criminal justice and third sector stakeholders, Third Sector Research Centre, Working Paper 34. www.birmingham.ac.uk/generic/tsrc/documents/tsrc/working-papers/working-paper-34.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2014.

Ministry of Justice. (2010). Breaking the cycle: Effective punishment, rehabilitation and sentencing of offenders. London: Ministry of Justice.

Ministry of Justice. (2015). Prison population figures: 2015. Population bulletin December 2015. www.gov.uk/government/statistics/prison-population-figures-2015. Accessed January 7, 2016.

Mobley, A. (2010). Garbage in, garbage out? Convict criminology, the convict code, and participatory prison reform. In M. Maguire & D. Okada (Eds.), Critical issues in crime and justice. Thought policy and practice (pp. 333–349). London: Sage.

Murray, J. (2005). The effects of imprisonment on families and children of prisoners. In A. Liebling & S. Maruna (Eds.), The effects of imprisonment. Willan: Cullompton.

Newbold, G., & Ross, J. I. (2012). Convict criminology at the crossroads: Research note. The Prison Journal, 93(1), 4–10.

Prison Reform Trust. (2015). Bromley briefings: Prison fact file (autumn). London: Prison Reform Trust.

Richards, S. C., & Ross, J. I. (2001). Introducing the new school of convict criminology. Social Justice, 28(1), 177–190.

Ross, J. I., Darke, S., Aresti, A., Newbold, G., & Earle, R. (2014). Developing convict criminology beyond North America. International Criminal Justice Review, 24(2), 121–133.

Ross, J. I., & Richards, S. C. (Eds.). (2003). Convict criminology: Belmont. California: Wadsworth.

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Social exclusion Unit. (2002). Reducing re-offending by ex-prisoners. London: ODMP.

Stewart, A. J., & McDermott, C. (2004). Gender in psychology. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 519–544.

Sykes, G. (1958). The society of captives: A study of a maximum security prison. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Van Manen, M. (2006). Researching lived experience: Human sciences for an action sensitive pedagogy (2nd ed.). Ontario: The Althouse Press.

Webster, C. (2007). Understanding race and crime. Berkshire: McGraw-Hill Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Aresti, A., Darke, S. Practicing Convict Criminology: Lessons Learned from British Academic Activism. Crit Crim 24, 533–547 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-016-9327-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-016-9327-6