Abstract

Corporate crime is often misrepresented in crime media as individual wrongdoing with minor consequences. Despite considerable research on corporate crime in news, there has been no examination of quality media sources, upon which this paper focuses. This paper presents an exploratory study of the first week of framing corporate crime in UK-based online quality press outlets: The Guardian, The Independent, and The Telegraph. It does so by examining three major corporate crimes of the last decade: the Grenfell Tower fire, the London Inter-Bank Offered Rate (LIBOR) manipulation, and Volkswagen emissions manipulation. Methodologically, the paper is based upon an adapted version of Robert Entman’s media theory of framing by using the framing elements of perpetrator, cause of crime, victimization and punishment to explore what and how frames are being used in each outlet. It is found that even the most critical mass media outlets resort to accidental narrative frames that fail to address criminal (in-)justice. I conclude with a discussion of the implications of these findings for an understanding of the variance in quality press outlets’ frames of corporate crime that warrants further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is not surprising, or new, that the most prevalent news sources distort the reality of crime. This is also reflected in public perceptions of criminality (Smolej & Kivivuori, 2006; Jewkes, 2015). Mass media headlines are dominated by violent crimes, while the crimes of corporations and other powerful actors receive little to no attention (Greer, 2017). Health and safety crimes become accidents, tragedies or disasters, frauds become fixes and scams, while environmental crimes appear as spills and releases. These narratives become almost expected as most mass media sources are large corporations which depend on funding from other corporations through advertising, making it likely that they will be less rather than more critical of corporate wrongdoing. (Foster & Barnetson, 2017).

While there is some criminological inquiry in the field of corporate crime media portrayals, most of the research is now outdated, as the print media on which these studies were based are no longer as common as their online counterparts (Clemente & Gabbioneta, 2017). Given that online outlets are relatively unexamined, this paper aims to advance the field of corporate crime media portrayals by shifting the focus on more contemporary media outlets: online news. I conduct an exploratory case study of online ‘quality press’Footnote 1 outlets (The Guardian, The Independent, and The Telegraph) with national readership to explore whether there are differences between their reporting of three corporate crime cases. These online quality press sources are the online siblings of the UK broadsheet newspapers bearing the same name, except The Independent which is published solely online. The cases analyzed are the Grenfell Tower fire, the Volkswagen emissions case, and the Barclays manipulation of the London Inter-Bank Offered Rate (LIBOR). In each case, the analysis focuses on the immediate aftermath of the incident, namely the first week, as that is when most frames are formed.

Methodologically, this paper makes an innovative contribution by drawing on the media concept of framing, rarely used within criminology. This method is used mostly in media studies and political science, studying how events are identified through language, metaphors, messages, and other linguistics (Kuypers, 2010). It is useful for understanding how, why, and how important these are in the construction of media reports. I use Entman’s (2003) definition of framing rooted in four framing elements, while adapting these to suit criminological research by aligning them with the four pillars of criminology: perpetrator, cause of crime, victimization, and punishment. Seeking an answer to these four elements allows for determining the overall frames for each outlet.

My exploratory analysis reveals that the portrayals of corporate crime in quality press are not as homogenous and one-sided as previous research seems to suggest. Even though the overall frames tend to ignore systemic factors contributing to the prevalence of corporate crime, it is crucial to acknowledge that different types of news outlets may be more or less likely to frame corporate crime as crime, thereby recognizing that some mass media outlets have the potential to challenge hegemonic narratives about corporate criminality.

In the following sections, I first present the challenges of researching media and crime with a specific focus on the crossover between corporate and media interests. Next, I present the current state of the literature on corporate crime media portrayals. Then, the main section of the article is concerned with presenting the results of my exploratory analysis in the three outlets one after another, structured through their portrayal of the four framing elements of perpetrator, cause of crime, victimization, and punishment. Finally, I conclude with a discussion of the implications of these findings for a more comprehensive understanding of corporate crime coverage in quality press sources.

Media, crime, and corporate power

Media can be understood as a sense-making device through which the public accesses knowledge about events which then contributes to producing, legitimizing, or challenging wider hegemonic attitudes towards social issues and realities, such as politics, economics, or crime (Herman & Chomsky, 1988; Katz, 1987; Williams, 2008). It plays a role in creating and mirroring individual and societal perceptions, actively framing realities in a certain way (Lynch & Stretsky, 2003; Greer, 2017; McCombs, 2005; Jewkes, 2015). Reporting a story involves selective coding of information and stories get reported using schematics of interpretation, also known as frames (Entman, 2007). These are often aligned with the philosophical, economic, and political goals of news sources, meaning that what is being reported will most likely be distorted (Reiner, 2002; Cissel, 2012). This is especially true for crime news as crime is a highly politicized subject that can receive a variety of representations across non-fictional media (Dowler et al., 2006; Greer & Reiner, 2012).

It is thus critical that we understand that media is implicated in reproducing “narrowly hegemonic conceptions of criminality, disorder, and (in)justice” (Williams, 2008, p. 473). King and Maruna (2009) argue that media use ‘narrative archetypes’, that is, accepted and recognized discourses of crime and justice that are easily interpreted by the readers, also supported by Entman’s theory of framing used in this paper. This is not to claim that the relationship between crime media portrayals and perceptions is not linear (see Greer & McLaughlin, 2017) – media is not solely responsible for creating public opinion, even if media perceptions are known to be crucial in how the general public perceives the criminal justice system (Barak, 1988). Put simply, media does not tell the readers what to think, but what to think about (McCombs & Shaw, 1972), meaning that understanding the framing of issues is vital for media scholarship.

It is a common observation that the media tends to prioritize reporting on specific categories of criminal activities, such as violent crimes, sexual offenses, and gang-related incidents (Greer & Reiner, 2012). Lynch and colleagues (2000) found that there were 47 police-reported homicides were covered in over 4,000 articles in local news. Other crimes, especially those committed by the powerful and corporations, are rarely covered in the crime news discourse (Cavender & Mulcahy, 1998; Hupp Williamson, 2018).

The lack of coverage of corporate crime news could be partly attributed to the overlap between corporate and media interests. These include the issue of power dominance, wherein the powerful may have the financial capital to engage in libel and defamation suits, meaning the media must be cautious when publishing accusations that may tarnish corporate reputations (Levi, 2006). Scholars also note that many corporations – including those that break the law – advertise in the media. Journalists could, therefore, have less freedom to criticize a corporation if their employers rely on advertising funding, particularly in cases where the same shareholders may be found in the news media conglomerate and the offending corporation (Cissel, 2012). Further, given that corporate actors may be the only source of information about the corporations, they can influence how certain issues concerning themselves get reported (Berry, 2016).

There is also a general neglect of corporate crime in crime news which Levi (2006) attributes to political pressures and its lack of newsworthiness. After all, many financial corporate crimes may get coverage in financial news instead as legitimate and illegitimate conduct is harder to differentiate from legitimate conduct. This was most apparent in the Enron case which was initially framed as creative accounting practices by news outlets (Barlow & Barlow, 2010).

Reiner (2002) adds that most mainstream news outlets are overtly conservative which may contribute to their unwillingness to challenge hegemonic narratives about wider political or ideological systems. Barlow and Barlow (2010) and Lofquist (1997) concur, finding that journalists often fail to challenge hegemonic crime and justice narratives in mainstream news, although there may be differences in crime discourses based on the political orientation, or ideological stance, of different news outlets. Media outlets more aligned with right-wing political orientations may report less corporate crime than others (Benediktsson, 2010). Hupp Williamson (2018) suggests a closer investigation of how the political orientation of media outlets may misrepresent the reporting of corporate crime, providing a further rationale for this paper.

Corporate crime media portrayals

Existing research on corporate crime media portrayals is limited compared to overall crime media research. Scholars have previously investigated corporate crime narratives in print media, reporting a presence of media bias attributed to the exercise of power (McMullan, 2006); reproduction of hegemonic values (Lofquist, 1997), fear of libel/defamation suits (Machin & Mayr, 2012), corporate ownership (Lynch et al., 2000; Cissel, 2012), or neo-liberal markets (Williams, 2008). However, the landscape of corporate crime media portrayals is limited, mostly concentrating on either a within-case analysis, or a narrow range of media outlets, with analysis of quality press outlets particularly lacking (McClung & Johnson, 2010).

Moreover, the existing research of corporate crime portrayals in newspapers has been criticized for being outdated (Weare & Lin, 2000; Herring, 2009); especially in the context of new (online) technologies and the speed of information dissemination in the 21st century. Given that online media outlets are now recognized as the predominant source of information – with, for example, 66% of UK adults accessing their news on the internet (Ofcom, 2022) – there is a need for a more contemporary research perspective incorporating this shift. The present paper aims to address this gap by combining insights from media studies, criminology, and political science and conducting an exploratory analysis of a type of news outlet that has not yet received much attention.

Scholars in criminology and media studies point out that corporate crimes tend to go unreported within mass media, not least as many aspects of them may not be perceived as newsworthy, especially in national news (Wright et al., 1995). However, even when these crimes are reported, they are carefully constructed to suggest that they are isolated, not preventable, and not foreseeable (Slapper & Tombs, 1999). Some believe this may be unsurprising as journalists tend to frame corporate crimes as individual rather than systemic (Cavender & Mulcahy, 1998). In doing so, news media “decontextualizes corporate crimes, eliding the very organizational dimension that is their defining characteristic and obscures the larger structural context of the behavior” (Vaughan, 1999; McMullan, 2006 in Cavender & Miller, 2013, p. 918).

Cohen et al. (2017) examined media portrayals of large-scale corporate frauds and found sensationalism and bias in their portrayals. Media tended to use simple language to explain complex financial crimes, despite the debilitating impact they have on the economy. Schifferes and Coulter (2012) reported similar findings and attributed this to businesses influencing media and media dependence on corporate advertising. Corporations also have enough capital to hire professional PR firms to shape coverage being disseminated to the news outlets, thereby having the ability to influence the news (Davis, 2011). Another means of corporate media control was found in Cissel’s (2012) investigation of the Occupy Wall Street movement. She found a conflict of interest between New York Times (NYT) shareholders who also held shares in other corporations – the NYT was more prone to use frames in the interests of business elites, downplaying and even dismissing the reasons behind the movement. Furthermore, corporations are also able to impact media reporting practices because they are the main sources of information about specific markets (Picard, 2014). In these various ways, corporations can exercise influence over media. As McMullan (2006, p. 930) puts it, “media truth-telling coincides with the exercise of power”. Another consistent aspect of corporate crime media portrayals is the individualization of responsibility found across financial, environmental, or health and safety corporate crimes (Barlow & Barlow, 2010; Benediktsson, 2010; Hupp Williamson, 2018; Lofquist, 1997; Williams, 2008). However, Schifferes and Coulter (2012) acknowledge that different news outlets generate slightly different frames in their corporate crime coverage which is worthy of further exploration.

Corporate crimes are complex, perhaps with a lack of fit to much academic criminology (Tombs, 2010) , let alone being easily grasped by a non-academic audience in a short piece of media reporting, be it a TV news segment or a news article. Media discourses lack the complexity and detail to represent corporate crime production (Hupp Williamson, 2018; Ras, 2021). Instead, more emphasis is placed on reducing corporate crime to deviations from the norm, and issues, instead of criminal behavior which undermines their seriousness in the first place (Machin & Mayr, 2012; McMullan, 2006).

Nevertheless, when the harms of corporate crime resemble those of street crime, it may be included in crime news (Burns & Orrick, 2002; Lofquist, 1997). Both studies use a comparative case study design to compare media portrayals of one corporate crime and one ‘traditional’ crime. They find that there is much focus on consequences and harm caused by the crime itself. However, an explanation of what produced corporate crime is rarely provided, and hegemonic perceptions about corporate crime tend not to be challenged.

Rationale and research questions

The current state of corporate crime media research presents a few uncertainties: the lack of a unified analytical approach, the lack of focus on quality press, and a far too common slippage and lack of clarity between corporate crime, problems, scandals, and disasters. Many studies have previously examined the issue of corporate crime media narratives across national media sources (Wright et al., 1995), tabloids only (Machin & Mayr, 2012), or comparisons between local and national papers (McMullan, 2006). Hupp Williamson (2018) recommends analyzing differences across cases and media outlets and Machin and Mayr (2012) highlight the short supply of research assessing the extent to which corporate crimes (as opposed to scandals) are conceptualized by the media. To date, there are no studies examining corporate crimes in quality press, presenting a unique opportunity for this research to explore the state of corporate crime in quality press outlets.

I intend to do this by conducting an exploratory study of three cases of corporate offending, focusing on their immediate aftermath in three UK-based national online quality press sources. Doing so will provide an opportunity to explore how online quality press presents these issues and whether there are any differences between how they frame the same events. Focusing on cases that are unquestionably criminal – a case of manslaughter, financial fraud and breaking of environmental law, respectively – will offer an introductory insight into whether cases that are clearly criminal (let alone those that are more ambiguous) get framed as lacking in seriousness.

Simply, this paper builds on existing research in three ways: it employs methodology previously overlooked within criminology, it explores sources not often used in corporate crime media studies, and it explores whether there are any differences across multiple quality news sources. I do this by asking the following research questions:

Explore what frames are given most salience during the first week of coverage in online quality press articles that discuss the LIBOR case, the Volkswagen case, and the Grenfell case.

Consider how these frames differ in each outlet based on their framing of the perpetrator, cause of crime, extent of victimization, and proposed punishment.

Case studies

The next section provides a short overview of the corporate crime case studies used in this paper. The cases were sampled using the critical case sampling strategy to explore how the most prominent cases of the 2010s were framed. The case studies are based on a small dataset within a short timeframe. This does, however, allow for a deeper qualitative analysis of each case study, while also reflecting the fact that corporate crime research in general tends to proceed incrementally, for a variety of reasons not least those related to the availability of and access to data. (Tombs & Whyte, 2003). These caveats notwithstanding, comparing coverage of three cases across three newspapers allows as we shall see, the highlighting of differences in each outlet’s coverage.

Nor is it claimed here that the data below is generalizable to every corporate crime portrayal in quality press.

, so no claim here regarding representativeness; but at the same time, there is no need to accept that the use of any case study needs to ‘be diminished by a belief that the findings may be idiosyncratic’ (Bryman, 1988, p. 88). Indeed, Flyvbjerg has argued that it is possible to ‘generalize based on a single case, and the case study may be central to scientific development via generalisation as a supplement or alternative to other methods’. Further, he claims, ‘formal generalisation is overvalued as a source of scientific development, whereas “the force of example” is underestimated’ (Flyvbjerg, 2006, p. 228). Thus, logical generalizations can be made even from studying a small number of critical cases (Patton, 1990). Flyvbjerg (2006) also argues that case study-based generalizations are central to scientific development given they demonstrate the practical example of a phenomenon. I am clear, then, that what is presented here may reflect peculiarities but not mere idiosyncrasies.

As such, this paper claims to present particularities in an exploratory way, not emerging trends.

Grenfell tower fire

Grenfell Tower was a council-administered tower block in Kensington, London which caught fire on the 14th of June 2017, causing 72 fatalities and over 70 injuries. The residents had campaigned against the non-compliance with health and safety regulations in the building for months before the fire (Tombs, 2020). This included an insufficient number of fire escapes and sprinkles, so the fire that had originated in one of the flats spread rapidly throughout the building, then further exacerbated by the non-fire-resistant cladding. Before Grenfell, there were dozens of other council buildings that were not health and safety compliant (Booth, 2017). Additionally, the Fire Protection Association and the Grenfell Action Group have been lobbying for an industry-wide review of the fire safety conditions of council buildings; both were ignored by the government and the council (Wainwright & Walker, 2017). At the time of writing, in November 2022, the Grenfell Tower Inquiry ordered by then Prime Minister, Theresa May, has yet to produce its final report, but it is certain to conclude that the deaths were entirely preventable (Tombs, 2020). Following the publication of the final report, the Metropolitan Police will decide whether to refer criminal charges against the corporations and government bodies involved in the fire to the Crown Prosecution Service (Booth, 2022).

Volkswagen emission manipulation

The Volkswagen diesel emissions case came to light when the US Environmental Protection Agency charged the company with Clean Air Act violations. Volkswagen diesel engines in up to 11 million vehicles between 2009 and 2015 had been programmed to falsify emissions to pass test requirements in laboratory settings, even though in real-world driving they were emitting up to 40 times over the allowed limit. These vehicles were also marketed as environmentally friendly. Thus, the company was violating environmental law as well as mis-selling, and this was done with the knowledge of the executives (Hanlon, 2015). Volkswagen paid out a combined settlement of $14.7 million in criminal charges in the US, recalled the faulty diesel vehicles and paid out a class-action settlement of $242 million in the UK in May 2022 (Ridley, 2022).

LIBOR manipulation

The UK’s Serious Fraud Office charged Barclays (and other banks) with manipulating the LIBOR rate submissions between 2005 and 2009 to reduce losses, gain profits, and protect their reputation (McConnell, 2013). LIBOR rates were calculated daily based on submissions from traders in international banks. This process was not overseen by any independent bodies, nor based on any hard data. Though the act of manipulating the whole financial market may seem victimless, customers who had loans, mortgages, or investments dependent on the LIBOR rates had their interest rates manipulated. Several individual traders were found guilty of fraud, and Barclays agreed to pay a combined fine of $435 million to the UK and US authorities and an additional $110 to US municipalities. In comparison, the fines given by European authorities went up to $9 billion (McBride, 2016). Even though the harm of such criminality is not directly visible, the ability of decision-makers to manipulate a rate of interest on a global scale seriously threatened the stability of the global financial economy.

Framing theory as a methodology

This paper uses the concept of framing (or framing analysis) to analyze the interpretation and understanding of texts in a broad sense that help readers label and categorize what is being presented (Scheufele, 1999). In media research, framing is concerned with how media relies on established patterns of understanding to socially construct realities. It helps to “grasp the fears and pains of a class, a community, or a nation, and then to crystallize their understanding of a problem.” (Ryan, 1991, p.74). Framing analysis goes beyond content analysis, recognizing that frames may not be immediately observable and that researchers should pay attention to how suggestive language is used to highlight one aspect of reality over others (Entman, 1993). For example, in the instance of corporate crime, the media may put more salience on how actions may have impacted the company’s stocks and shareholders rather than tangible impacts on victims. This does not necessarily mean the latter does not get mentioned in the text, but rather that the former is both presented more vividly and is foregrounded in the text.

The use of framing analysis is most prevalent in political science (Entman, 2003) but is increasingly employed in media studies and sociology – it was described as one of the most fertile research areas in journalism (Matthes, 2009), perhaps for being rooted in the work of the sociologist Goffman (1974). Goffman’s scholarship was later developed into a methodological approach by, amongst others, Entman (1993), upon whose conceptual definition this paper is based.

Framing theory acknowledges the presence of biases that may influence journalists’ portrayals of a story. Scheufele (1999) identifies societal norms, values, journalists’ ideologies, and interest group pressures among these biases (see Van Gorp, 2007). This is also consistent with Bourdieu’s journalistic field theory which describes the interaction between the micro-level of the inner workings of the field (such as journalists’ position within society and the inner pressures of the newsroom) and the symbolic power exercised through frames used within the media texts which are based on reinforcing wider inequality (Benson, 2006). As such, media hegemony (see Gramsci, 1971) and the presence of corporate power in media’s representations of news are acknowledged, which is significant for corporate crime representations and the impact corporate ownership may have on media representations (Gilens & Hertzman, 2000).

Pan and Kosicki (1993) view framing as a process of highlighting sections of an issue which eventually becomes key in impacting public perceptions. Framing definitions are only partial, as they must be established through specific theoretical frameworks (D’Angelo, 2019). However, in the face of some criticism (see for example Matthes, 2009), D’Angelo (2009) states that there is no need for a unified conceptual definition of framing across disciplines, but that we should focus on multi-dimensional and multi-paradigmatic research that transposes boundaries of disciplines in social science, a commitment shared in this paper.

Linstrõm and Marais (2012) emphasize the need to explicitly outline the operational definitions of framing used by the researchers. Given that framing is uncommon in criminological enquiry, I rely on the most common definition of framing posed by Entman (1993). Despite being initially conceived for investigating crises and scandals, I adopt it here for critical criminological analysis. This is possible because Entman’s ideas about framing are very much aligned with how corporate crime gets reported: often, the media assign the label or disaster or scandal of corporate crimes, making this method appropriate and poignant for this paper. As such, the operational definition of framing in this paper states that:

To frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particularproblem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/ ortreatment recommendation (Entman, 1993, p. 52).

This definition is operationalized via four framing elements – problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation. The researcher seeks to find the answer to these four elements in the text and organize it thematically to observe the overall frames used in the text. Entman (1993) also claims that framing involves selection, or determining what facts of the event get reported, and salience which refers to the prominence of one explanation over others within a text not necessarily based on the frequency of mentioning the topic, but rather the prominence and strength of suggestion employed in describing a subject.

Framing elements

Some researchers suggest using framing elements to improve the reliability of framing analysis (Matthes & Kohring, 2008). These are crucial in framing analysis, as seeking answers to them helps with develop overarching frames. Given that framing is uncommon in criminological studies, I adapted Entman’s framing elements for criminological scholarship using my presupposed definition of crime and the branches of what criminology seeks to study. Table 1 describes the relationship between Entman’s four elements and those used in this paper. They were developed with minimal conceptual overlap, drawing upon previous research in the realm of corporate crime media portrayals which included the content categories of intent, harm, cause, responsibility and risk (Lofquist, 1997; McMullan, 2006; Williams, 2008).

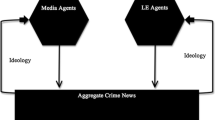

This paper relies on cluster analysis, as per Matthes and Kohring (2008), in which the text is first analyzed to identify the mention of a framing element. The mentions are extracted and subsequently analyzed thematically to identify the thematic categories presented. The thematic categories are organized into clusters when they describe similar themes. An example can be observed in Fig. 1 where a cluster was created for thematic categories of contextualizing harm and lack of control and policies. An overall frame is then determined for each thematically similar cluster. The main advantage of this approach is the availability of criteria (the elements) when it comes to identifying the frames as it suggests the number of clusters that should be extracted (ibid.).

Expectedly, many news frames are common and repetitive, such as the human impact frame, the economic frame, or the conflict frame (Neuman et al., 1992). Within corporate crime media studies, legalistic, scapegoating, contextual, reputational and conflict frames have previously been identified (see for example Cissel, 2012; Schifferes & Coulter, 2012; Clemente & Gabbioneta, 2017). It is important to emphasize that the frames were developed by a single coder with a background in corporate crime media studies using a constructivist paradigm, so the final frames used here must be viewed in that context.

The frames found in this piece of exploratory research were somewhat aligned with previous findings. Two frames were identified in each of the outlets. The Guardian’s frames were contextual and punitive by discussing the background that gave rise to the offending, while salience was given to the punitive measures that should be taken as a response to the crimes. The Independent used economic and human-interest frames, focusing instead on the economic impacts of the case on shareholders and the company as well as on victimization centered around people. Lastly, The Telegraph used populist and sensational frames with hyperbolized language, focusing predominantly on victimization and sensationalizing the impact of the cases, particularly in the graphic descriptions of victims escaping the fire and the impact of car emissions on public health.

The research process of identifying news frames could be positioned somewhere beyond content analysis, and between discourse and thematic analyses based on strong emphasis on the use of language, though it is more culture-bound than content analysis (Reese, 2007). Linstrõm and Marais (2012) recommend focusing on the following two categories of framing devices: rhetorical devices such as metaphors, depictions, and catch-phrases (adapted from Gamson & Lasch, 1983), as well as syntactical, thematic, and rhetorical structures (adapted from Pan & Kosicki, 1993); and secondly, technical devices (headlines, sources, quotes, subheadings, and others). These were all assessed throughout the research process, which is described in more detail below.

Data selection and method

Given that this research aims to explore frames in online quality press, the data was sourced from UK-based quality news sources that are published online and have a national readership. The data obtained from news sources is publicly available on the websites of the news outlets, as well as available to access in the Figshare data repository: https://figshare.com/s/c1f74367cdf08659eadc.

News sources

According to the latest research by a UK news regulator Ofcom (Office of Communications), online news is the second most used type of news used by the UK public where 66% of those over 16 years old access their news. From these, The Guardian is the second most overall read online news outlet, with 18% of adults over 16 using the website to access their news online. This is compared to the BBC NewsFootnote 2 website which receives 62% of online news traffic. The other two quality press outlets are comparable with The Telegraph receiving 7% and The Independent 6% of overall online news readership respectively (Ofcom, 2022). Generally, the Guardian is perceived to be the most-read quality news outlet in the UK, receiving more than double the reach of both the Independent and Telegraph (GNM press office, 2020).

The Guardian is a left-leaning quality press news outlet with readers tending to support Labour and Liberal Democrat parties in the UK. The readers are more likely to be older and more educated. The Independent is viewed as similarly slightly left or centrist. The Telegraph has support from the Conservative majority (YouGov, 2017). It is also important to note that The Telegraph differs from The Guardian and The Independent, as it offers no free content without needing a subscription. In June 2022, The Telegraph had over half a million digital subscribers (TMG, 2022).

The political orientation of the media is expected to impact the frames that are used when describing corporate crime, and corporations in general, as conservative views in the UK are likely to be pro-corporate and pro-business, while left-leaning views are likely to be more critical of corporations and corporate power (YouGov, 2017). That said, some claim that, ultimately, all mass news outlets are overtly conservative (Reiner, 2002) which might suggest that there would be relatively few differences between their portrayals of corporate crime.

Research design and limitations

This study uses an exploratory research design as it is most fitting to conduct preliminary analyses of previously unexplored subjects (Stebbins, 2001), in this case, quality press’ frames of corporate crime. It uses a relatively small sample of cases and a case study design also aligned with the nature of exploratory research. This has two consequences: first, this research can be used as a basis for more longitudinal analysis and second, researchers should be careful when interpreting and generalizing its findings.

According to research, the interpretation of breaking news events is most impacted in the first few days of the event (Clemente & Gabbioneta, 2017). Interest in the event typically spikes initially but fades after a few days (Schifferes & Coulter, 2012). This observation underpins the decision taken to only focus on the first week of coverage post-exposure for each caseFootnote 3. Using the LexisNexis database, I took the most popular in-depth article from each day of the week (7) in each case (3) and each outlet (3). This resulted in a sample of 21 articles (7 × 3 = 21) for each of the outlets with the final sample size across the three cases being 63 articles. The average length of each article was 600 words. I then read through the full sample of 63 items to familiarize myself with it, and then via a second read-through I noted where the content addressed my four framing elements - perpetrator, cause of crime, victimization, and punishment. I considered what frames emerged from each news outlet based on identifying the thematic category of the answers to the four framing elements for each individual case. Lastly, I organized separately the data from each of the three outlets and synthesized the framing of each case to identify the overall frames used by each outlet across the three cases.

The scope of this study may be considered a methodological limitation. But given that news outlets are not likely to change their frames after they started reporting a story (Entman, 2007) and that there was little variance in how each outlet portrayed the cases, the findings of the study remain meaningful. As discussed in the case study section, this is not to claim simple generalization – though Williams (2000) discusses moderatum generalizations that are more tentative and limited, but still valid in small-sample qualitative research. Tsang (2014) also finds case studies underappreciated for their potential for theoretical generalizations. Braun and Clarke (2013) estimate 10–100 secondary sources as sufficient for thematic analysis, further supporting my sample size, especially given the exploratory nature of my paper.

Another relevant observation relates to my sample of corporate crime cases – three different types of crime are covered, namely a health and safety crime, an environmental crime and a financial crime. Further, each occurred or came to light in a different year (2017, 2015, 2012), and each received varying amounts of media (and political) attention. Additionally, Grenfell differs from the other two cases, as the reporting started with the fire and the information then slowly came to light, as opposed to Volkswagen and LIBOR where the cases essentially started with the discovery, after some regulatory investigations had already been conducted. Therefore, more information may be known about the latter two cases which may have allowed more complete frames to be formed. However, this may be alleviated by the fact that Grenfell Tower received publicity prior to when the story about the fire broke, with the residents publicly campaigning for health and safety compliance in the building for several months before.

Results

As mentioned in the methodology section and Fig. 1, the overall frames were assigned through thematically analyzing and synthesizing the answers to the four framing elements: perpetrator, cause of crime, victimization, and punishment during the first week of coverage after the story broke. Even though each article was evaluated separately, the results below are organized according to each outlet respectively.

The guardian

Overall, the frames found in The Guardian offered something of a critical perspective that linked the specific case to wider concerns about the whole industry or sector at issue, while placing it into the context of limited controls of corporate activities. Even though some articles mentioned individual offenders and mistakes instead of illegal behavior, the overall frames used by the Guardian can be described as contextual and punitive, which is reflected in the fact that criminal prosecution was suggested as the appropriate punishment. Generally, the frames used by the Guardian are amongst the most critical in this sample which is consistent with its left-leaning political affiliation. The following section will address each framing element separately.

Perpetrator

There was an ambivalence in how the perpetrator was framed case-by-case – coverage of Volkswagen and LIBOR both mention individual offenders, such as traders and testing technicians. At the same time, the LIBOR case mentioned that while the traders may have altered the submissions, more damage was done when the banks attempted to protect their reputation and, as the case had market-wide participation, the markets were seen as conducive to this type of behavior. Similarly, frames in the Grenfell case were more likely to describe the context in which the crime occurred –decreasing council budgets, lacking health and safety regulations in council tower blocks, government ignorance of warnings from the Fire Protection Association, and the residents’ association campaigning to review the fire safety regulations (Walker, 2017). It was also noted fire safety regulation may have been neglected, noting that they have “not been subject to an in-depth review since 2006” (Wainwright & Walker, 2017). This is interesting and unexpected, as previous research into corporate crime media portrayals lacks any reference to systemic factors (see Schifferes & Coulter, 2012). This all indicates that the political orientation of the outlet could have an impact on how corporate crime gets framed.

Cause of crime

The Guardian framed the causes of the corporate crimes in the sample as related to a lack of controls in place, greed, or budget cuts. The latter frame is more related to Grenfell than the other two cases, as council budget cuts were blamed for the failure to properly maintain health and safety regulations in council buildings which had contributed to the rapid spread of the fire at Grenfell. The two former causes were mostly observed in the LIBOR case. Initially, Guardian blamed the traders and their pursuit of profit and bonuses, which were cited as their main motivation (Treanor, 2012). However, the news outlet then went further to suggest that since multiple banks were implicated in LIBOR manipulation over several years, then the blame lies within the banking sector. “This is about more than one man…This is about the culture and practices of the entire banking system” (Treanor, 2012). In other words, the individuals who engaged in the illegal practices were enabled by the flawed system that had no controls in place (Tombs, 2012; Cohen et al., 2017).

Overall, the causes of the crimes only received limited attention compared to the other framing elements. This is consistent with previous research (McMullan, 2006) – media often focus on the consequences rather than the causes of corporate crimes, thereby reinforcing, or at least not challenging, the accidental origins of such crimes.

Victimization

The extent to which harms and victimization were framed differed across the cases. In Grenfell, understandably, more attention was paid to the direct victims who were either killed or harmed by the fire, as well as referring to the wider harm caused to people living in council and other high-rise buildings which did not meet adequate health and safety standards. For Volkswagen and LIBOR, the discourse was more directed towards the corporation as a victim with the share value being decreased and the reputation being tarnished, especially in the case of Volkswagen (Rushe & Farrell, 2015). Coverage of LIBOR lacked any clear focus on victimization apart from mentioning public trust in capitalist markets being diminished - but this is perhaps not surprising as the harms of the case are not diffused and not as obvious nor graphic as in the case of Grenfell. Not much attention was paid to the environment being harmed by the increased Volkswagen emissions, so the case was not placed into the wider context of environmental crimes, an observation again supported by previous research (Hupp Williamson, 2018; Lynch et al., 2000). This was unexpected and contrary to much of the sample being somewhat critical of power and ‘the establishment’, and more aligned with academic than popular knowledge. Thus, the failure to frame the case as impactful on the environment somewhat separated this from the critical character of the other frames. Lastly, coverage mentioned that states were equally impacted due to increased subsidies connected to environmental automobiles, which was only addressed within this news outlet.

Punishment

Despite the lack of language synonymous with crimes and illegalities, the cases were described in the context of deserving of criminal punishment, or a public inquiry that may lead to punishment under criminal law. In the case of Volkswagen, it was suggested that “the company should be severely punished for its immoral, devious and deceitful approach to public health risks as well as mis-selling to car drivers” (Ruddick & Farrell, 2015). Generally, the framing of this case can be compared to the contextual frame found by Clemente and Gabbioneta (2017) in the left-wing affiliated national newspaper used in their analysis of the Volkswagen case. The LIBOR case was framed in terms of the need for criminal charges for individuals (Treanor, 2012), while the Volkswagen case went as far as to suggest a global criminal investigation (Ruddick, 2015). Grenfell differed from the other two cases due to the involvement of state actors in the crime, so a public inquiry was proposed as a response, while the coverage was less about punishment with more focus on describing either the immediate consequences of the fire or the wider context of health and safety in council tower blocks.

The Independent

The Independent’s framing of the sample was slightly different to that of the Guardian, most apparent in the proposed punishments for LIBOR and Volkswagen, as well as the overall framing of the Grenfell case with economic and human-interest frames dominating the outlet. Salience was given to the economic and business implications rather than placing the crimes in the context of harmful corporate activities, or how the system may encourage such behavior, even though references are made to previous “scandals” of the corporations. This suggests the media either cannot connect these points or is purposely overlooking them to remain hegemonic. The human-interest frame was apparent in The Independent’s framing of individual perpetrators, and the suggestions that punishment in the LIBOR case should be focused on consequences for the executives and traders. This is contrasted with the Guardian’s frames suggesting a review of the whole industry and global criminal investigations.

Perpetrator

The framing element of the perpetrator was the subject of extensive speculation in the case of Grenfell, but less so in the Volkswagen case which made no specific reference to the perpetrator of the crime except stating that the company had engaged in illegal behavior. On Grenfell, the outlet assigned the blame to government negligence to act on reports that had raised the lack of fire safety in council buildings (Baynes, 2017). It also points to the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (KCTMO), the organization which managed the tower and wider housing estate, and which had been approached multiple times by the residents to complain about the lack of health and safety compliance. As opposed to the Guardian, no budget cuts or era of deregulation were mentioned. For LIBOR, there was a tendency to blame traders and their managers, as well as the government for minimizing the manipulation, as manipulating benchmark rates was not criminalized at the time of the occurrence (Morris, 2012). This is not surprising, nor new, as individual blame for financial crimes is common even in cases that clearly point to structural issues that give rise to the offending (Cohen et al., 2017). There was much scapegoating of the individuals who were thought to go against the values of the company by “cheating the system and fixing the market” (Hughes, 2012). According to the Independent, this was certainly not an issue for the whole banking industry, even though multiple banks worldwide were accused of the same crime.

Cause of crime

This was perhaps the most interesting and salient element discussed in both Grenfell and LIBOR cases. Coverage of the Volkswagen case only makes one suggestion on the cause of the crime by mentioning that Volkswagen “had used a software fix to avoid a costly engineering fix for its dirty diesel engines” (Connett & Merrill, 2015), suggesting that a cost-benefit analysis may have been conducted before deciding to fit the emission cheating devices into the vehicles. This brought to mind echoes of the Ford Pinto and Toyota Camry cases (Pardue et al., 2013). Discussion of the LIBOR case offered conflicting views on the cause of crime, ranging from individual greed to the normalization of the practice in the industry, to blaming the government for not criminalizing the manipulation earlier (Morris, 2012).

With Grenfell, the Independent spends a lot of space discussing what the cause might have been, despite initially claiming the cause is unknown and will remain so until the investigation is conducted. Interestingly, however, the blame was predominantly assigned to the cladding, without making a specific reference as to how and why the cladding was allowed and approved to be used (Kentish, 2017). A recurring point here is that the cladding was used to improve the physical appearance of the building (Griffin, 2017), while salience was also given to technical details of the cladding, quoting ‘experts’ and ‘reports’ as the sources to increase credibility, consistent with Williams’ findings (2008). However, much of the discussion is vague and fails to detail specific resident campaign organizations and their concerns, or to present specific reports that are being used as information sources.

Victimization

Compared to The Guardian, The Independent narrowly focuses on the immediate victims of the Grenfell fire (the residents) and the LIBOR manipulation (Barclays, the offending bank’s share values and reputation). In the LIBOR case, content on the impact on consumers was entirely lacking. For Volkswagen, however, the human-interest frame comes into play the most: the Independent refers to the manipulated emissions being a public health crisis which has been linked to lung illnesses such as asthma and breathing problems, quoting the statistics of environmental deaths from pollution which in the UK is estimated at 50,000 victims yearly (Sheffield, 2015). This frame is, however, accompanied by much focus on the tarnished reputation and decreased share value of Volkswagen, commonly encountered in existing research (Lofquist, 1997).

Punishment

The framing of proposed punishment in the cases was wide-ranging. For Grenfell, there were suggestions of criminal investigation to establish the responsible individuals or institutions (Kentish, 2017). For Volkswagen, there were calls for the CEO to resign as well as for an EU-wide investigation to ensure that emission manipulation has not extended to EU vehicles (Connett & Merrill, 2015). LIBOR, however, saw disciplinary resolutions in the form of CEO resignation, as “there needs to be a more general change of leadership including the chief executive” (Grierson, 2012). It also raised the issue of criminal prosecution, though this was only applicable to individual traders who manipulated the rate rather than at the level of the bank itself (Morris, 2012). The bank-wide manipulation undertaken by the executives was justified by being for the “greater good” of stabilizing financial market health during the financial crash of 2008. Thus, only the possible redundancy of bank executives is suggested as a “change of culture is needed” (Grierson, 2012), even though many other international banks also participated in the manipulation. This is further exemplified by providing a summary of the sanctions in other countries, making the proposed punishment in the LIBOR case widely ambivalent. One consistent thought seems to be that the behavior of the banks can go unpunished if the participating individuals are punished, whereas market-wide participation suggests a broader cultural or systemic problem.

The Telegraph

The frames found in The Telegraph to describe the sample cases were much more aligned with what one would expect to find in typical mass media discussions of corporate crime, albeit not in quality press outlets. The structure of the language was embellished and exaggerated, with words like “screams and tears”, “death-trap”, “gas-guzzlers”, and “filthy” being used to describe the cases, quite in contrast to the language found in the Guardian and Independent which was not as strong nor sensationalized. Additionally, the headlines in The Telegraph also made use of word capitalization, further contributing to the presentational hyperbole. As such, this is in line with the overall frames that can be described as populist and sensational, discussed for each of the elements below.

Perpetrator

Like the other two outlets, The Telegraph also lacks discussion about the perpetrator of the Volkswagen manipulation, as it is implicit that it was the company itself. LIBOR and Grenfell follow similar patterns in which blame is assigned to the ‘usual suspects’ without many references to the wider contexts in which the crimes occurred. For LIBOR, this means that individual traders and senior managers were blamed for the crime, as the “bank’s senior management instructed staff to make artificially low Libor submissions“ (Telegraph, 2012). Much focus is on individual responsibility, even though it is also mentioned that 70% of the rates submitted between 2006 and 2007 were changed, which would suggest a much bigger, systematic problem, though this is not commented on in any detail. Lastly, in the Grenfell case, The Telegraph accuses the property management company, KCTMO, of failing to ensure the fire safety was maintained, the government for ignoring warnings of experts and residents, and the council for “awarding [the contract] to the cheapest bidder regardless of the quality of works” (Knapton, 2017). However, more time is spent on describing the process of the tower’s renovation and the conflicts between the ‘rude, intimidating workers’ and the ‘courteous residents’. The outlet also spends some time discussing fire safety in council buildings more broadly, which would suggest systemic responsibility. Yet, it is not framed as such in the bigger picture.

Cause of crime

The Telegraph discussed the potential causes of the crimes extensively in the case of Grenfell and LIBOR, less so for Volkswagen. For the latter, the cause was assigned to the lack of oversight from the government and the pursuit of profit by the company which puts profit over public health concerns (Hanlon, 2015). There was an ambivalent discussion of the causes of the LIBOR manipulation. As mentioned earlier, there were two stages of the manipulation, the first was focused on individual profits for the traders and the second was done at the management level during the financial crash of 2008 to improve the health and image of the bank (Trotman, 2012). This distinction was clearly emphasized in the sample – the individual offenders who used profits and bonuses as their main motivation were strongly contrasted with the senior managers who used the manipulation to protect the reputation of the bank, framed as something positive as if managers only became involved when the bank needed protection (Wilson, 2012). The Telegraph also mentions that “everyone knew, and everyone was doing it” (Bowers, 2016), suggesting that the practice was widely normalized, and part of the culture of trade banking, so that people participated because others were participating too.

The Grenfell case is also the subject of various explanations of the offending, but the most salience is given to driving the costs down in lieu of profit by the council and the KCTMO, the property management company. Additionally, many numbers are used in connection with the cost-benefit analyses connected to the crime, stating that “Flame-retardant cladding could have been fitted to Grenfell Tower for just £5,000 extra” (Knapton, 2017); further exemplifying that the involved parties placed much more importance on cost-savings rather than safety. This is not an uncommon finding, most health and safety-related corporate crimes are the product of such decision-making (Cooper & Whyte, 2018; Tombs & Whyte, 2013). Similar to The Independent, the use of the particular cladding is also discussed as improving the outlook and energy efficiency of the building (Sawer, 2017).

Victimization

The most salient point in each case in the Telegraph was the focus on victimization. In Grenfell, this was done by explaining the ‘screams’ and ‘cries’ of victims, citing multiple witnesses and victim families (Milward, 2017). Quotes are given from witnesses of the fire who were going through “heartbreak” having watched loved ones being lost, as well as from friends and families of victims on site (ibid.). Interestingly, in the LIBOR case, The Telegraph is the only outlet to mention the impact that the manipulation might have had on customers with LIBOR-dependent products, such as mortgages and loans (Trotman, 2012), so the emphasis is not solely on the reputation and the share value of the company, though these are also mentioned as harms resulting from the crime.

The Volkswagen frames yield the most interesting results. Salience is given to the impact of the crime on the victims of air pollution rather than the damage to the environment itself which is entirely overlooked (Hanlon, 2015). Many statistics are used to emphasize this point, quantifying premature deaths resulting from air pollution where the numbers vary with each article. First, 7,000 fatalities yearly in Britain then becomes 30,000, then becomes 12,000, which then becomes 10,000 in London alone and 500,000 in Europe in any given year (Kirk, 2015). Despite their flawed use of inconsistent statistics - without quoting official sources of them - the articles are clearly constructed to provoke the reader to worry about their health rather than to react negatively toward the company. As expected, shares and the reputation of the company are also quoted as being harmed by the manipulation.

Punishment

The discussion of the framing element of punishment was not as extensive as that of victimization. The salience placed on fatalities in the Volkswagen case would suggest that the outcomes are synonymous with manslaughter, however, the proposed punishment is far from criminal. The most appropriate sanction, according to The Telegraph, is to recall and replace all impacted vehicles as well as to carry out an industry review of other car makers (Knapton, 2017). This further corroborates that the depictions within The Telegraph are embellished for dramatic effect rather than for prompting radical responses towards corporate crime. For LIBOR, the sanctions proposed were orientated towards punishing the individuals involved with disciplinary actions, especially banning them from working for the financial services, while also calling for the resignation of the CEO (Wilson, 2012). The outlet is not critical of the LIBOR submitting practice itself, only of the few ‘rule-breakers’ that engaged in the manipulation practice, despite quoting that this was an industry-wide issue. Similarly, not much salience was placed on sanctions for the Grenfell case, other than stating that fire safety compliance should be more enforced without suggesting a clear strategy to do so (Sawer, 2017).

Discussion

Media framing helps readers make sense of events by compartmentalizing all available information into simple schemes that are easily interpreted, and, in so doing, promoting certain interpretations over others. Indeed, the three news outlets analyzed in this paper promoted a different interpretation of each of the cases that varied from the more counter-hegemonic frames found in the Guardian to the populist frames of The Telegraph, even though all papers fall under the quality press umbrella. In fact, the three outlets could almost be positioned on a spectrum, ranging from a critical engagement with the topics at hand observed in The Guardian to somewhat critical frames focusing on the economy in The Independent to highly populist and sensationalist frames in The Telegraph. Moreover, this appears consistent with the readership and political leaning of each of the outlets that were described in the News Sources section.

Additionally, each case offered different particularities and different types of offences, some of which are more frequently synonymized with crimes (Machin and Mayr, 2013). Manslaughter and bodily harm in the Grenfell case are more likely to be portrayed as crimes than the ‘intangible’ harms of destabilizing global economic systems in the LIBOR case, or the environmental harm of the Volkswagen case. Interestingly, however, The Telegraph was more engaged with the impacts of environmental crime on public health, albeit, in a sensational way, that was missing in the other two outlets. On the other hand, all three outlets failed to call out the environmental damage that was caused by Volkswagen’s cheating in emission tests, and some explanations offered were oversimplified and individualized, a particularity also found in existing research (Schifferes & Coulter, 2012).

Contrary to previous research (Lofquist, 1997; McMullan, 2006), one mass media outlet (the Guardian) was able to provide contextual and punitive frames of corporate crimes to some extent despite using language that synonymized problems and mistakes with crimes and negligence. While some discussion of the systemic factors that gave rise to the offending was offered in the Grenfell case, discussions of both Volkswagen and LIBOR cases tended towards identifying ‘bad apples’ in need of punishment rather than giving salience to how systems may facilitate the offending. The contextual frame was more apparent when discussing the causes of crime as the absence of laws/policies and the punitive frame was mostly apparent in suggesting severe and criminal punishments for the crimes.

All three outlets recognized that the crimes of the Grenfell Tower were less individual and more systemic and suggested some degree of criminal punishment. The fact of the case which is most salient is the low-cost cladding that exacerbated the fire. The Independent repeatedly mentions the non-fire-resistant cladding responsible for the fire but does not explicitly identify the individuals and decision-making processes involved in its installation. Similarly, McClung’s (2006) study attributes the fatalities of the salt-mine collapse to the collapse itself, without specifying the cause of the collapse. The harms caused to the residents were more central in the Independent and The Telegraph than in the Guardian with the latter discussing more systemic factors of the harms for all council housing tenants living in similar buildings. Overall, the differences between the outlets were less apparent in the Grenfell case.

Conclusion, limitations, and future research

Media has the power to shape attitudes as it informs the public of current events (Greer & Reiner, 2012). Corporate crime research has not kept up with the increasing incidence and coverage of corporate crimes, which this paper aimed to address. It sought to provide some preliminary results that are exploratory in nature of how the UK national online quality press depicts three cases of corporate crimes by using framing analysis of the first week of their coverage. The findings have several implications. To some extent, the quality press can be critical of corporate wrongdoing and portray it in a wider context of harmful corporate activities. However, by and large, quality press narratives were found to be hegemonic by being oversimplified and lacking frames synonymous with crime. As such, readers may perceive corporate crimes as expected consequences of a system that are not challenged beyond individual blame, a finding consistent with that of Machin and Mayr (2012). The extent of victimization, its severity and the level of social impact all make corporate crimes far more dangerous than traditional crimes, often recognized in academic research, so the minimization of this by the press can justifiably be characterized as complicity in these negative outcomes.

As acknowledged above, the scope of research in this paper is limited – the sample included only one article from each day in the immediate aftermath of the crimes, so care must be taken about generalizing from the results found here. However, this was expected as the research was exploratory in nature. The research findings can be built upon in the future, be it with a more longitudinal analysis of how the frames change with developments in cases across longer periods, as these could impact the predominant frames encountered in the news. For instance, at the time of writing, the Grenfell inquiry has just concluded with the final report being expected in the next year, so the case still receives media attention which could be suitable for a more longitudinal analysis. This would allow for more detailed comparisons to be made across the corporate crime spectrum and to further assess the disparity between the perceptions of the seriousness of corporate crime portrayed in the news as opposed to the knowledge available through academic research. Additionally, future research might foreground the question of the political leanings of newspapers to consider how these may impact their crime narratives.

Further, news media may no longer be the dominant information sources on corporate crime – people increasingly receive their crime news and knowledge through alternative, more contemporary sources, such as social media, podcasts, or documentaries. Analysis of these could yield even more interesting, interdisciplinary results by branching out into cultural criminology. Podcasts are known to have the potential to challenge hegemonic narratives on crime and as such, are worthy of further academic exploration.

Data availability

The data was obtained from news sources is publicly available on websites of the news outlets, as well as available to access in the Figshare data repository: https://figshare.com/s/c1f74367cdf08659eadc.

Notes

Quality press is a term used in British journalism that marks those news outlets that are often deemed to be more ‘serious’, giving detailed media reports rooted in high-quality journalism. These are often positioned as being distinct from tabloids which use sensationalist language to frame events.

BBC News is not classified as a quality press outlet as it is owned publicly.

Grenfell: June 14th − 21st, 2017 Volkswagen: September 18th − 25th, 2015; LIBOR: June 27th - July 3rd, 2012.

References

Barak, G. (1988). Newsmaking Criminology: Reflections of the media, Intellectuals, and crime. Justice Quarterly, 5(4), 565–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418828800089891.

Barlow, D. E., & Barlow, M. (2010). Corporate Crime News as ideology: News Magazine Coverage of the Enron case. The Journal of Criminal Justice Research (JCJR), 1(1), 1–36.

Baynes, C. (2017). Ministers ‘Ignored Warnings on Fire Safety’ before Grenfell Tower inferno [online]. The Independent. Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/grenfell-tower-fire-latest-chief-fire-office-ronnie-king-government-ignore-warnings-gavin-barwell-a7795731.html.

Benediktsson, M. O. (2010). The deviant organization and the bad apple CEO: Ideology and accountability in media coverage of corporate scandals. Social Forces, 88(5), 2189–2216. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40927543.

Benson, R. (2006). News Media as a journalistic field: What Bourdieu adds to New Institutionalism, and Vice Versa. Political Communication, 23(2), 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600600629802.

Berry, R. (2016). Part of the establishment: Reflecting on 10 years of podcasting as an audio medium. Convergence, 22(6), 661–671. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856516632105.

Booth, R. (2017). Grenfell Tower: 16 Council Inspections Failed to Stop Use of Flammable Cladding [online]. The Guardian. Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/jun/21/grenfell-tower-16-council-inspections-failed-to-stop-use-of-flammable-cladding.

Booth, R. (2022). ‘Every death was avoidable’: Grenfell Tower inquiry closes after 400 days [online]. The Guardian. Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/nov/10/every-death-was-avoidable-grenfell-tower-inquiry-closes-after-400-days.

Bowers, S. (2016). Libor-Rigging Scandal: Three Former Barclays Traders Found Guilty [online]. The Guardian, Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/jul/04/libor-rigging-scandal-three-former-barclays-traders-found-guilty.

Bryman, A. (1988). Quantity and quality in Social Research. Unwin Hyman.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE.

Burns, R. G., & Orrick, L. (2002). Assessing Newspaper Coverage of corporate violence: The Dance Hall Fire in Goteborg, Sweden. Critical Criminology, 11, 137–150.

Cavender, G., & Miller, K. W. (2013). Corporate crime as trouble: Reporting on the corporate scandals of 2002. Deviant Behavior, 34(11), 916–931.

Cavender, G., & Mulcahy, A. (1998). Trial by fire: Media Constructions of Corporate Deviance. Justice Quarterly, 15(4), 697–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418829800093951.

Cissel, M. (2012). Media framing: A comparative content analysis on Mainstream and Alternative News Coverage of Occupy Wall Street. The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, 3(1), 67–77.

Clemente, M., & Gabbioneta, C. (2017). How does the media Frame Corporate Scandals? The case of german newspapers and the Volkswagen Diesel scandal. Journal of Management Inquiry, 26(3), 287–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492616689304.

Cohen, J., Ding, Y., Lesage, C., & Stolowy, H. (2017). Media Bias and the persistence of the expectation gap: An analysis of Press Articles on Corporate Fraud. Journal of Business Ethics, 144(3), 637–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2851-6.

Connett, D., & Merrill, J. (2015). Volkswagen Emissions Scandal Spreads to Europe and Threatens to Embroil More Models and Rival Carmakers [online]. The Independent, Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/volkswagen-emissions-scandal-spreads-to-europe-and-threatens-to-embroil-more-models-and-rival-10513290.html.

Cooper, V., & Whyte, D. (2018). Grenfell, Austerity, and institutional violence. Sociological Research Online, 1(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780418800066.

D’Angelo, P. (2019). Framing theory and journalism. The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118841570.iejs0021.

Davis, A. (2011). ‘News of the Financial Sector: reporting on the City or to it?’. Open Democracy, Retrieved October 10, 2022, from https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opendemocracyuk/news-of-financial-sector-reporting-on-city-or-to-it/.

Dowler, K., Fleming, T., & Muzzatti, S. L. (2006). Constructing crime: Media, crime, and popular culture. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 48(6), 837–850.

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x.

Entman, R. M. (2003). Cascading activation: Contesting the White House’s frame after 9/11. Political Communication, 20(4), 415–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600390244176.

Entman, R. M. (2007). Framing Bias: Media in the distribution of power. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00336.x.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363.

Foster, J., & Barnetson, B. (2017). Dead today, gone tomorrow: The framing of Workplace Injury in canadian newspapers, 2009–2014. Canadian Journal of Communication, 42(4), 611–629. https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2017v42n4a3025.

Gamson, W. A. & Lasch, K. E. (1983). The political culture of social welfare policy. In S. E. Spiro & E. Yuchtman-Yaar (Eds.), Evaluating the welfare state: Social and political perspectives (pp. 397–415). Academic Press.

Gilens, M., & Hertzman, C. (2000). Corporate ownership and news bias: Newspaper coverage of the 1996 Telecommunications Act. Journal of Politics, 62(2), 369–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-3816.00017.

GNM press office (2020). New data shows Guardian is the top quality and most trusted newspaper in the UK [online]. The Guardian Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/gnm-press-office/2020/jun/17/new-data-shows-guardian-is-the-top-quality-and-most-trusted-newspaper-in-the-uk.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis. Free Press.

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the prison books. International Publishers.

Greer, C. (2017). News Media, victims and crime. In P. Davies, C. Francis, & C. Greer (Eds.), Victims, crime and society (pp. 20–49). SAGE.

Greer, C., & McLaughlin, E. (2017). News power, crime and media justice. In A. Liebling, L. McAra, & S. Manura (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Criminology (6th ed., pp. 260–283). Oxford University Press.

Greer, C., & Reiner, R. (2012). Media made criminality: The representation of crime in the Mass Media. In M. Maguire, R. Morgan, & R. Reiner (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Criminology (3rd ed., pp. 376–416). Oxford University Press.

Grierson, J. (2012). Libor Investigation Decision due ‘Within a Month’ [online]. The Independent, Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/libor-investigation-decision-due-within-a-month-7903021.html.

Griffin, A. (2017). Grenfell Tower cladding that may have led to fire was chosen to improve appearance of Kensington block of flats [online]. The Independent, Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/grenfell-tower-cladding-fire-cause-improve-kensington-block-flats-appearance-blaze-24-storey-west-london-a7789951.html.

Hanlon, M. (2015). Europe Must Now Come Clean on Diesel [online]. The Telegraph, Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/earth/environment/11878435/Europe-must-now-come-clean-on-diesel.html.

Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (1988). The political economy of the mass media. Pantheon

Herring, S. C. (2009). Web content analysis: Expanding the paradigm. In J. Hunsinger, L. Klastrup, & M. Allen (Eds.), International Handbook of Internet Research (pp. 233–250). Springer.

Hughes, D. (2012). Barclays ‘Not Alone’ in Interest Rate Scandal, Says George Osborne [online]. The Independent, Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/barclays-not-alone-in-interest-rate-scandal-says-george-osborne-7896470.html.

Hupp Williamson, S. (2018). What’s in the Water? How Media Coverage of Corporate GenX Pollution Shapes Local understanding of risk. Critical Criminology, 26(2), 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-018-9389-8.

Jewkes, Y. (2015). Media and crime (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Katz, J. (1987). What makes crime ‘news’? Media Culture and Society, 9(1), 47–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/016344387009001004.

Kentish, B. (2017). Grenfell Tower fire caused by faulty fridge on fourth floor, reports suggest [online]. The Independent, Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/grenfell-tower-cause-fridge-faulty-fourth-floor-london-kensington-disaster-latest-a7792566.html.

King, A., & Maruna, S. (2009). Is a conservative just a liberal who has been mugged? Exploring the origins of punitive views. Punishment & Society, 11(2), 147–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474508101490.

Kirk, A. (2015). Volkswagen Emissions Scandal: Which Other Cars Fail to Meet Pollution Safety Limits? [online]. The Telegraph, Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/road-and-rail-transport/11881954/Volkswagen-emissions-scandal-Which-other-cars-fail-to-meet-pollution-safety-limits.html.

Knapton, S. (2017). Grenfell Tower Refurbishment Used Cheaper Cladding and Tenants Accused Builders of Shoddy Workmanship [online]. The Telegraph, Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/06/16/grenfell-tower-refurbishment-used-cheaper-cladding-tenants-accused/.

Kuypers, J. A. (2010). Framing analysis from a rhetorical perspective. In P. D’Angelo, & J. Kuypers (Eds.), Doing news framing analysis (pp. 302–327). Routledge.

Levi, M. (2006). ‘The Media Construction of Financial White-Collar Crimes’. The British Journal of Criminology, 46(6), 1037–1057. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azl079.

Linstrõm, M., & Marais, W. (2012). Qualitative news frame analysis: A methodology. Communitas, 17, 21–38.

Lofquist, W. S. (1997). Constructing crime: Media Coverage of Individual and Organizational Wrongdoing. Justice Quarterly, 14(2), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418829700093321.

Lynch, M. J., & Stretsky, P. B. (2003). The meaning of Green: Contrasting criminological perspectives. Theoretical Criminology, 7(2), 217–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480603007002414.

Lynch, M. J., Stretesky, P., & Hammond, P. (2000). Media Coverage of Chemical crimes, Hillsborough County, Florida, 1987-97. The British Journal of Criminology, 40(1), 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/40.1.112.

Machin, D., & Mayr, A. (2012). Corporate crime and the discursive deletion of responsibility: A case study of the Paddington Rail Crash. Crime Media Culture, 9(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741659012450294.

Matthes, J. (2009). What’s in a Frame? A content analysis of Media Framing Studies in the World’s leading communication journals, 1990–2005. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 86(2), 349–367.

Matthes, J., & Kohring, M. (2008). The content analysis of Media Frames: Toward improving reliability and validity. Journal of Communication, 58(2), 258–279.

McBride, J. (2016). Understanding the Libor Scandal, Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/understanding-libor-scandal.

McClung, S., & Johnson, K. (2010). Examining the motives of Podcast users. Journal of Radio & Audio Media, 17(1), 82–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376521003719391.

McCombs, M. (2005). A look at agenda-setting: Past, present and future. Journalism Studies, 6(4), 543–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700500250438.

McCombs, M., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of Mass Media. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(2), 176–187. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2747787.

McConnell, P. (2013). Systemic operational risk: The LIBOR Manipulation scandal. Journal of Operational Risk, 8(3), 59–99. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2328036.

McMullan, J. L. (2006). News, Truth, and Recognition of Corporate Crime. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 48(6), 905–940. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjccj.48.6.905.

Milward, D. (2017). ‘The whole building has gone’: Witnesses describe screams and tears at Grenfell Tower fire in London [online]. The Telegraph, Retrieved September 11, 2022, from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/06/14/whole-building-has-gone-witnesses-describe-screams-tears-tower/.

Morris, N. (2012). Will we see City bankers behind bars? [online]. The Independent, Retrieved September 11, 2022, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/will-we-see-city-bankers-behind-bars-7904450.html.

Neuman, W. R., Neuman, R. W., Just, M. R., & Crigler, A. N. (1992). Common knowledge: News and the construction of political meaning. University of Chicago Press.