Abstract

In the advancing understanding of the crime-terror nexus, organized crime and terrorist entities are increasingly seen as capable of pursuing multiple agendas simultaneously, with the potential to ultimately reach convergence. Applying Makarenko’s theoretical work on crime-terror convergence, this article sets out to explain the persistence of organized crime in Iraq after the fall of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) Caliphate, based on a literature study and three expert interviews. The vacuum caused by the Caliphate’s fall led to fierce competition between remnants of ISIS and Iran-backed Shia factions of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), and a rearrangement of control over ISIS’ criminal enterprise. The Iraq-Syria border is used as a hub for the smuggling of weapons, drugs, oil, and people by both the ISIS remnants and the Shia PMF factions, while the border areas and roads leading to Baghdad are focal points for imposing illicit taxation. We argue that in post-Caliphate Iraq, ISIS remnants can be seen as hybrid criminal-political entities, while the Shia PMF factions cannot be defined as such in a definite manner. In their competition for power, both actors exploit local idiosyncrasies to garner support among the local population. By strengthening both their criminal and ideological-political components, these actors continue to destabilize the already fragile Iraqi state. Moreover, because Iran-backed Shia PMF factions obtained legitimacy and state backing as liberators from ISIS and became embedded in the Iraqi state apparatus, the state itself became a crucial contributor to the crime-terror nexus in post-Caliphate Iraq.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This article is based on the Master thesis ‘The persistence of organized crime in post-Caliphate Iraq’, written by the first author and supervised by the second author, and available at https://www.ubvu.vu.nl/scripties/getpdf.cfm?facid=14&id=6984. The authors thank Joris van Wijk and Hossein Mojtahedi, as well as the three anonymous reviewers, for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this submission.

In the post-9/11 era, a growing body of research has focused on the ‘crime-terror nexus’ or the relationship between organized crime and terrorism. These studies not only concern the involvement of terrorist organizations in organized crime, such as weapons and drug trafficking or money laundering,Footnote 2 but also focuses on how organized criminal actors and terrorist actors cooperate or even converge (see e.g., Sanderson, 2004; Shelley & Picarelli, 2005; Felbab-Brown, 2005; Roth & Sever, 2007; Hutchinson & O’Malley, 2007; Thachuk & Lal, 2018; Omelicheva & Markowitz, 2019). Increasingly, organized crime and terrorist entities are seen not as essentially and fundamentally different, but as capable of pursuing multiple agendas simultaneously, progressing into a deeper level of collaboration through alliances and tactical appropriation, ultimately reaching convergence at some central point (Makarenko, 2004; De Boer & Bosetti, 2015). This new analytical lens has put into question the utility of existing categorizations and distinctions between ‘criminal’ and ‘terrorist’ actors. Progressively, the nexus came to be understood as far more complex, difficult to predict, shaped by socio-economic, political and geographic factors, and the degree and nature of state involvement (Omelicheva & Markowitz, 2019: 4). Convergence between organized crime and terrorism may be particularly evident in ‘weak states’ and conflict-affected countries with high levels of corruption, porous borders, and ineffective law enforcement (Wu & Knoke, 2016). Vianna de Azevedo and Pollak Dudley (2020) have argued how such a mix of characteristics represents the backbone of every kind of relationship that exists between organized crime and terrorism. At the same time, some authors warn that the influential and politicized narrative of convergence should be assessed critically (Omelicheva & Markowitz, 2021).

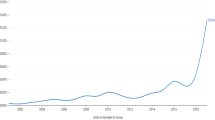

One pertinent example of convergence between organized crime and terrorism is the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), an actor that has been widely designated as a terrorist organization and became extensively involved in organized crime.Footnote 3 At the time of the proclamation of the ISIS Caliphate, in June 2014, the estimated income of ISIS was $2 billion and around that same time it was described as the richest terrorist organization in the world (Forbes International, 2015; McCoy, 2014; Heißner et al., 2017). Although ISIS’ funding has decreased precipitously with their loss of territory and military defeat in 2019, the group still relies on a well-preserved financial system that has successfully served it for years (Johnston et al., 2019). According to the US Treasury Department (2021), ISIS’ financial situation remains largely unchanged, whilst the group continues to move funds in and out of Iraq and Syria, often relying on logistical hubs in Turkey. The group’s financial reserves are estimated at $100 million, and it is believed that part of it remains buried in the core of the conflict zone or kept with trusted custodians and couriers (United Nations [UN], 2020a).

Given ISIS’ extensive involvement in organized crime, a pertinent question is how this criminal enterprise evolved after the fall of the Caliphate, and who took control over it. In fact, despite the territorial ‘victory’ over ISIS, organized crime seems to be on the rise in post-Caliphate Iraq.Footnote 4 Besides ISIS, other criminal and terrorist actors have entered the scene – a mix of mostly Shia and Sunni factions who have integrated into the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF). The fall of the Caliphate was followed by increased competition between ISIS and the PMF to establish and maintain control over strategically important areas such as borders, ports, and roads leading to the Iraqi capital, Baghdad (Khaddour & Hasan, 2020). While the evolvement of organized crime before and during ISIS’ Caliphate has been addressed in academic literature (see e.g. Williams, 2009; Blannin, 2017; Clarke et al., 2017; Le Billon, 2021), the situation of post-Caliphate organized crime in Iraq so far has not.

With this article, we aim to fill that gap, based mainly on a literature study, and supplemented with three expert interviews. We will do so by mapping the current organized crime landscape. Subsequently, we will apply the theoretical framework on crime-terror convergence developed by Makarenko (2004, 2011) and refined by Makarenko and Mesquita (2014) in an effort to explain the persistence of organized crime in post-Caliphate Iraq. Although the idea of convergence and ISIS has been touched upon by Vianna de Azevedo (2020) regarding the group’s cooperation with human smuggling networks, so far, it has not been comprehensively applied to the case of post-Caliphate Iraq. While ISIS until its military defeat represented one of the most prominent examples of convergence in recent years, the fall of the Caliphate – similar to the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 – created a power and security vacuum in the country. Such an environment provides a fertile ground for organized crime, terrorism, and their convergence, and thus Makarenko’s model has potential to help disentangle the evolution of the crime-terror nexus in post-Caliphate Iraq. At the same time, as we will argue, the nature of the factions under the PMF that became involved in organized crime, call into question the applicability of Makarenko’s model, because of their state-embedded nature.

After a brief methodological paragraph, we will outline the theory on the crime-terror nexus, and Makarenko’s model in particular. This is followed by a discussion of the development of the organized crime landscape before, during and since the ISIS Caliphate. Subsequently, we will apply Makarenko’s convergence model to explain the persistence of organized crime in post-Caliphate Iraq and zoom in on the fragile post-Caliphate Iraqi state and the role of state-embedded actors. We conclude that while Makarenko’s model on the crime-terror convergence is beneficial in explaining the convergence between economic and ideological goals of ISIS remnants, its application on the PMF Shia factions is not definite. In their competition for power, both actors exploit local idiosyncrasies to garner support among the local population. By strengthening both their criminal and ideological-political components, these actors continue to destabilize the already fragile Iraqi state.

Methodology

This article is the result of a qualitative, mixed-methods case study of post-Caliphate Iraq, combining a literature review with a limited number of expert interviews. The study is based on an extensive review of academic articles, books, policy briefs, NGO and think-tank reports. This review was conducted for the dual purpose of formulating a theoretical framework and generating input for the case study. In order to be able to also incorporate the most recent events and developments relevant for the case study, in some cases (online) media reports and weblogs have been used. Some of the used sources may be biased, which can influence the reliability of the information. In addition, the authors have had to rely on reporting in English, which means the perspective may be biased and in line with a narrative that is dominant outside Iraq. For these reasons, as much as possible, information from media reports was checked and cross-compared from multiple data sources to minimize such bias. However, it must be kept in mind that evidence on recent events in Iraq is not always verifiable in an independent manner.

Due to the relative novelty of the topic of organized crime in post-Caliphate Iraq, and the scarcity of the literature, three expert interviews were conducted to corroborate findings from the literature and provide additional information. A combination of purposive and snowball sampling was used. Experts were approached if they had published an article or report relevant to the topic, conducted fieldwork in Iraq, or were referred to by another expert. Out of seven contacted experts, three responded and agreed to be interviewed. The interviews were conducted by the first author, during the months of May and June 2021 through video conference, because of restrictions in relation to the Covid-19 pandemic. All interviews were recorded and transcribed.

Respondents were offered the possibility to be anonymized throughout the study, in order to prevent any possible repercussions for them. The respondents were given a code (R1, R2, and R3), based on the chronological order of interviews. R1 is a researcher working on Iraq, R2 is a researcher working on the Middle East, especially on ISIS and foreign terrorist fighters in Iraq, R3 is a researcher working on ISIS in Iraq and Syria, especially on the illicit trade in antiquities as a way of funding. The interviews were semi-structured, using topic list of topics the researcher wanted to cover during sessions, including nature, scale and geography of organized crime in Iraq after the fall of the Caliphate, ISIS-remnants’ involvement in organized crime, the PMF’s involvement in organized crime, (potential) criminal collaborations between actors involved in organized crime, and corruption. Data obtained from the expert interviews were coded manually, without software, using coding schemes. To ensure confidentiality and security, the collected data were stored in a pseudonymized way on a separate secured data carrier. Until completion of this publication, the data were stored in a secured data repository at the research institute to which the authors are affiliated; afterwards, they were deleted on request of the respondents. Finally, input from a webinar, organized by the Center for International Criminal Justice (CICJ) in Amsterdam, ‘Iraq’s New Cycle of Radicalization; Cause for Alarm?’, on March 16, 2021,Footnote 5 was used for the case study.

Because of the lack of academic studies on the selected case, potential biases in the available information, and the limited number of expert respondents this study relies upon, it has to be stressed that our findings should be considered exploratory in nature. Nonetheless, as noted above, we have used and cross-compared data from multiple sources as much as possible, to ensure reliability and validity. This being an explorative case study, we believe the value is especially in its in-depth exploration of the utility and applicability of Makarenko’s model to a current and understudied case. We will suggest directions for further research in the final section.

Theoretical framework

The crime-terror nexus and Makarenko’s convergence model

The persisting links between organized crime and terrorism have resulted in an array of theories trying to explain the crime-terror nexus. Over the years, the understanding of the relationship between organized crime and terrorism has evolved. The definition of both the concepts of ‘organized crime’ and ‘terrorism’ is subject to extensive debate. It is important to note that these concepts can overlap, and any definition has its limitations. For the purposes of this article, we use the following definition of terrorism: “The use of violence or the threat of violence with the primary purpose of generating a psychological impact beyond the immediate victims or object of the attack for a political motive” (Richards, 2014: 230). We define organized crime as “a continuing criminal enterprise that rationally works to profit from illicit activities that are often in great public demand. Its continuing existence is maintained through corruption of public officials and the use of intimidation, threats or force to protect its operations” (UNODC, 2018).

Traditionally, organized crime and terrorism were seen as two distinct phenomena, separated by the profit-ideology dichotomy. Under this notion, crime was seen as a profit-maximizing, apolitical and non-ideologically motivated phenomenon, and terrorism as strictly ideologically motivated, without any profit driven actions (Ballina, 2011). While the dichotomy emphasized how a terrorist organization is different from a criminal enterprise, as it pursues political rather than economic goals, the lines that once separated organized crime from terrorism are increasingly blurred. In addition, the rigid dichotomy has been criticized because it overlooks the flexibility of the crime-terror nexus, where crime can serve as a mobilizer for terrorists, ensuring not only funding, but also effective recruitment, governance, and operational capabilities (Ballina, 2011; Rosas, 2020; Omelicheva & Markowitz, 2021). Since 9/11, the discussions started to focus on operational and organizational similarities, highlighting the intersection between organized crime and terrorist organizations, and their economic and ideological goals (Makarenko, 2004; Shelley, 2005; Shelley & Picarelli, 2005; De Boer & Bosetti, 2015; Wu & Knoke, 2016; Shelley, 2020). Theories then evolved around tactical and organizational links between criminal and terrorist organizations, highlighting the possibility of the convergence of their motives and activities (Omelicheva & Markowitz, 2021: 1544).

In this context, Makarenko (2004: 130) introduced the concept of a crime-terror ‘continuum’, illustrating how “a single group can slide up and down the scale – between what is traditionally referred to as organized crime and terrorism – depending on the environment in which it operates”. Makarenko argues that because criminal and terrorist groups share the same space of operation, it is theoretically possible that they reach a central point at the center of the continuum, where the traditional ideology-profit dichotomy is no longer visible. This is the point of ‘convergence’: “criminal and terrorist organizations could converge into a single entity that initially displays characteristics of both groups simultaneously; but has the potential to transform itself into an entity situated at the opposite end of the continuum from which it began”, changing the aims and motivations of the organization (Makarenko, 2004: 135).

Such convergence may manifest in various forms. The first form of convergence refers to criminal groups demonstrating political motivations. Criminal groups either use terror tactics to gain actual political influence and control by participating in political processes, or they use such tactics to gain control over lucrative economic sectors of a state, such as strategic natural resources, with the ultimate aim to take over political control (Makarenko, 2004). The second form refers to terrorist groups so heavily engaged in criminal activities that their continued use of political rhetoric merely provides a cover for their criminal activities, while behind that cover, they have transformed into a different type of group with different goals. The continued use of political rhetoric distracts attention of government and law enforcement from the criminal activities and helps terrorist organizations to secure support as this rhetoric is used to justify criminal acts (Makarenko, 2004).

Over the years, Makarenko (2011: 242) adapted her initial crime-terror continuum and emphasized how the convergence can unfold in two scenarios. The first is integration of two separate entities – a terrorist and a criminal one. The second is convergence of economic and ideological goals of one entity, creating a hybrid criminal-political entity. She further stressed how, since the convergence is mostly conceptual, it is the most difficult type of nexus to identify. In 2014, Makarenko and Mesquita introduced a refined crime-terror nexus model (Fig. 1), aiming to reflect on the ‘fluidity’ of the crime-terror nexus. According to Makarenko and Mesquita (2014), the nexus fluctuates within three convergence points, as depicted in Fig. 1: operation, organizational, and evolutionary convergence. The refined model uses the same stages as the 2004 crime-terror continuum but emphasizes the fluctuation of the crime-terror nexus rather than presenting this as a linear model.

Refined crime-terror nexus model (Makarenko & Mesquita, 2014, 260)

Makarenko (2004) holds that convergence can be fostered in a context of a weak or a failed state.Footnote 6 Such an environment can provide a “safe haven” for convergence, which has been referred to in the literature as a “black hole”. The “black hole syndrome” refers to situations in which the motivation of groups engaged in a civil war evolves from political to criminal, or situations where a converged, hybrid entity has successfully taken over control of the state, rendering it a “black hole state”. In the absence of a strong state, criminal and terrorist groups may constitute de facto governments, imitating characteristics of legal, formal state activities, and replacing the state in most of its functions, whilst furthering their involvement in activities that would be considered illegal by such structures (Makarenko, 2004).

The state as an actor in the crime-terror nexus

The discussion of Makarenko’s model above focused on the role of non-state actors in the crime-terror nexus. Increasingly, however, crime-terror nexus scholars have started criticizing existing, simplistic analyses that overlook the role of the state in the crime-terror nexus, understanding the nexus as a sole domain of ‘criminals’ and ‘terrorists’ (see Shelley, 2005; Omelicheva & Markowitz, 2019; Felbab-Brown, 2019). Omelicheva and Markowitz (2019) argue how, so far, weak or failed states have often been seen as a product, while they should be seen as a cause of the alliance between terrorist and criminal organizations. In conflict-affected regions, due to the absence of a strong state, the shadow economy is often by and large the only functioning economy, and criminal actors provide an alternative governance structure. In such an environment, individuals in need, as well as criminal actors, together with corrupted law enforcement, military, and politicians all have an interest in maintaining and expanding the illicit economy (Shelley, 2005). A situation may develop in which criminal groups as well as corrupted officials have a joint interest in maintaining the power vacuum and protract conflict. Therefore, crime can serve as a method of governance, representing a convenient justification to maintain control over economic and political resources (Felbab-Brown, 2019). In this respect, criminal groups, terrorist groups and state officials share the same interest. In such circumstances, Shelley (2005: 104) emphasizes how the crime-terror nexus extends beyond a marriage of convenience; it goes to the very heart of the relationship between organized crime groups and the state.

Although the emergence and the nature of the crime-terror nexus can often be explained from socioeconomic and geographic factors, such as marginalization of certain social groups, porous borders, or a (post) conflict setting, the state’s ability to form a relationship with criminal or terrorist actors and control the criminal economy is critical in shaping this nexus, according to Omelicheva and Markowitz (2019). The authors emphasize how actors involved in illicit activities can infiltrate politics, to establish control over military and security institutions, weakening the rest of the state apparatus. In this context, the state becomes a crucial part of the nexus, not only as an environmental factor but also as an active contributor. Actors who manage to establish control over (parts of) the state apparatus do not necessarily fit into a ‘state – non-state’ dichotomy. We will argue below that in the case of Iraq during and after the ISIS Caliphate, some actors involved in illicit activities who were part of the Iraqi state apparatus can be best described as ‘state-embedded’ actors; it is this type of actors that we refer to when we discuss the role of the Iraqi state in organized crime post-Caliphate.Footnote 7

(Pre-)Caliphate Iraq: Organized crime, terrorism and the competition for power

The organized crime landscape in Iraq in the past decades exemplifies how the symbiosis between organized crime and endemic corruption can erode a state’s legitimacy. In order to properly understand the conditions in which organized crime came to thrive in any situation, it is necessary to understand the “origins and beneficiaries of illicit or shadow economies and informal financial systems” (Omelicheva & Markowitz, 2021: 1550). In Iraq, organized crime was well-rooted in Saddam Hussein’s regime and intensified during the imposition of sanctions by the international community in 1990 (Williams, 2009). The criminalization of the state, uneven economic development, and the security apparatus operating as a state within the state made Iraq a fragile state on its way to becoming a failed state (Bouillon, 2012: 285). The US invasion in 2003, and the subsequent power and security vacuum enabled a great expansion of organized crime, diversifying the types of organized crime and actors involved. Corruption became a crucial instrument for criminal and terrorist groups, to prevent any attempt to disrupt their illicit activities.

A convergence of organized crime and terrorism increasingly started to manifest following the invasion. The lacking provision of welfare and essential services across the country was exploited by terrorist groups, engaging “in criminal activities as a funding mechanism to provide the resources necessary to maintain their social welfare activities and structures” (Williams, 2009: 53). As a result, criminal and terrorist groups started to provide alternative governance structures, and therefore economic stability and security (Williams, 2009). In addition, post-invasion instability created a convenient proxy battleground, where neighboring states and other regional actors played out their economic and military power struggles, furthering the domestic crisis (Lawlor & Davison, 2020).

Post-invasion instability provided an opportunity for expansion of Islamic extremism, with Abu Musab al Zarqawi pledging allegiance to Al-Qaida, and founding what is now known as ISIS, in 2004 (Glenn et al., 2019). ISIS’ ideology can be qualified as Salafi jihadist, a religious-political ideology based on Sunni Islamism, which strives for establishing a global caliphate. By 2012 ISIS exploited the chaos that emerged in Iraq and neighboring countries, rapidly seizing huge portions of Iraqi, as well as Syrian territory, ultimately proclaiming the Islamic State Caliphate on 29 June 2014 (Oosterveld & Bloem, 2017). ISIS has been using violence, including beheadings, executions, and attacks on foreign nationals and “apostate regimes in the Arab world”, to instill fear and generate a wider psychological impact beyond the group’s immediate victims (Byman, 2015). The ultimate, political motive of the group has been the establishment of an Islamic state with a religious authority over all Muslims, governed by the laws dictated by its strict Salafi-jihadi Islamist ideology (Johnston et al., 2016). Therefore, ISIS falls within Richard’s definition of terrorism.

From its emergence, ISIS has been involved in a myriad of illicit activities ranging from oil control and smuggling, illicit taxation, extortion, human trafficking, kidnapping for ransom, to illicit trade in antiquities, and allegedly drugs and human organs trafficking (Financial Action Task Force [FATF], 2015; UN, 2016; Clarke et al., 2017; Joint Counterterrorism Assessment Team, 2017; Lurie, 2020; Le Billon, 2021). While various forms of organized crime have been linked to ISIS, it can safely be concluded that revenues derived from the control over oil together with illicit taxation and extortion, were the sources of utmost importance, strengthening its resilience. Decades-old smuggling routes that emerged during the imposition of sanctions, and were extensively used following the US invasion, were continued to be used by ISIS and actors involved in the smuggling of oil and antiquities during the Caliphate (Giovanni et al., 2016; Le Billon, 2021; Morris, 2015). Although ISIS was defeated militarily in 2017 and its Caliphate formally ended in 2019, its potent ideology and fighters are still present in Iraq; we will return to this below.

As a counterforce, Iran is believed to have been using proxy armed forces in Iraq since the US invasion in 2003, aiming to spread Shia influence, and infiltrate Iraqi politics (Arraf & Schmitt, 2021). The security vacuum in Iraq, caused by ISIS’ seizure of Mosul in 2014, led Iran’s proxies to form and lead an ‘umbrella organization’ the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), strongly connected with Shia religious authorities in Iran and Iraq (Alaaldin, 2020).Footnote 8 Due to ISIS’ rapid expansion, the Iraqi government saw itself forced to turn to Iran, opening a path for Iran-backed groups to fill the vacuum left by the US withdrawal. The PMF were, therefore, seen at the time as the only option.Footnote 9 The PMF have been described as a hybrid actor, in between state and non-state actors, drawing power and funding from the Iraqi state and supporting the state’s agendas, while simultaneously acting autonomously, outside the state’s control (Mansour et al., 2019). The PMF are constitutionally integrated into the Iraqi army and had a crucial role in the liberation of Iraqi territory controlled by ISIS (Paktian, 2019; Alaaldin, 2020).Footnote 10 Hence, they could be qualified as ‘state-embedded’ actors. At the moment of establishment, the PMF consisted of 67 Shia factions, 43 Sunni factions, and 9 factions from minority areas south of Kurdistan, all unified in the fight against ISIS (Newlines Institute, 2021). The most prominent Shia factions operating under the PMF are Kata’ib Hezbollah (KH) – the strongest one closely linked to Iran’s Revolutionary Guards Corps and the elite Quds Force (IRGC-Quds) and Iran’s proxy Hezbollah – and Asaib Ahl al-Haq (AAH) (Knights et al., 2021a; Countering Extremism Project, n.d.). Both factions were established on strong Shia jihadi, anti-American ideological foundations, and are designated terrorist organizations by the US (US Department of State, 2009; 2020).

The available reporting suggests that AAH and KH, in line with Richard’s definition of terrorism, have been using violence for the primary purpose of generating a psychological impact beyond the immediate victims or object of the attack, for a political motive. For instance, they are believed to have carried out drone strikes on US targets and assassinations across Iraq, including the assassination of Hisham al Hashimi, a prominent Iraqi security expert who is believed to have been killed because he exposed the influence and the role of these Iran-backed factions in different activities, including organized crime (Arraf & Schmitt, 2021; Hassan, 2020). While we cannot verify whether the PMF are indeed behind these instances, the available reporting suggests that actors integrated within the PMF use violence and subsequent intimidation on a local, regional and international level to achieve a variety of political goals, including the infiltration in Iraqi political and security spheres and spreading Iranian influence. The PMF cannot, or at least much less so than ISIS, be seen as one coherent organization; rather, they constitute a conglomerate of fluid and adaptive networks, each with different strategies and capabilities, operating in a symbiotic relationship with the Iraqi power structures (Mansour, 2021). Within these networks, individual factions and commanders can act in a way that is in (seeming) contradiction with policies of the PMF as a whole.

However, despite exhibiting features of a terrorist group, the PMF cannot be described as such in a definite manner. The PMF have gained a certain level of legitimacy, territorial control, and (political) power without using terroristic violence as defined by Richards. For example, the PMF’s success in the fight against ISIS and their involvement in providing the Iraqi population with essential services and security “made the citizens trust these groups and forced the government to accept that the groups would need to be involved in preserving the security of the liberated areas” (Newlines Institute, 2021: 16). In this context, the PMF are more comparable to Afghan warlords, who are also perceived by parts of the population as ‘protection forces’ against the Taliban and corrupt government, than to an organization like ISIS. Additionally, while they have been mostly engaged in the same criminal activities, the scale and the nature of the PMF’s terrorist violence is incomparable to the violence used by ISIS, which is of a more brutal nature. Moreover, we consider the PMF’s acts of violence as multifaceted, as some can be described as terrorist acts aiming to generate wider psychological impact, while others are more accurately described as mafia-style extortion and assassinations.

Post-caliphate Iraq: Nature, scale and geography of organized crime

Turning to the focus of this article – the current state of organized crime in post-Caliphate Iraq – the main forms of organized crime recently reported are drug trafficking, smuggling of commodities, illicit taxation and extortion. It appears that since the fall of the Caliphate, Iraq became not only a crucial transit country for heroin originating from Afghanistan on its route to Syria, but also a large market for drugs mostly coming from Iran and Afghanistan (Abu Zeed, 2020; Adal, 2021). Heroin, opium, marijuana, methamphetamines, and various pills are distributed across Iraq and further to destinations such as Turkey, Syria, and ultimately Europe and North America (Abu Zeed, 2020; Shilani, 2020). The Iranian border, and its adjacent provinces, Diyala and Kirkuk, as well as ports in Basra, are the main areas for drugs entering the country (R1; Rubin, 2019; Jangiz, 2020). The Iraq-Syria border is a crucial smuggling hub for actors involved in illicit trade in cigarettes, medicines, weapons, oil, narcotics, artefacts, scrap metal, copper, cement, food, and electronics (Al-Hashimi, 2020b; Emirates Policy Center, 2021).

There are indications that human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation and forced labor is taking place across Iraq, particularly in Baghdad (Al-Rabehi & Al-Nasseri, 2019; Damon et al., 2019; Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, 2020). There are reports of foreign, mostly African, women, being lured to Iraq through recruitment agencies under false promises that they are going to work as secretaries, while in reality they are subjected to sexual slavery or domestic work and sexual abuse (R1; Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, 2021). In addition, according to this respondent there are reports of Yazidi women who have been victims of trafficking. After they were taken by ISIS, some Yazidi women had a hard time reintegrating into the community, and were particularly vulnerable to trafficking networks, that brought them to Baghdad where they were exposed to sexual slavery (Damon et al., 2019).

Besides Yazidi women, human trafficking networks reportedly lure displaced refugees under the false promise that they will help them resettle or help them with an asylum application for Western countries, and then bring them to Baghdad, Basra, and other cities in southern Iraq, where forced prostitution and modern-day slavery are increasing significantly (Damon et al., 2019; Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, 2020). According to the Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (2020), “in early 2020, the Iraqi government confirmed that sex trafficking has been taking place in massage parlors, coffee shops, bars, and nightclubs, where victims are being lured through social media and fake job offers.” Because of difficulties in obtaining information about human trafficking – said to be due in part to allegations that highly influential actors such as Shia religious clerics and the PMF factions are involved – there is an overall lack of evidence confirming the scale of human trafficking and clarifying the actors involved (Al-Maghaf, 2019; BBC, 2019).

Depending on the geographical area in which they operate, actors involved in organized crime across Iraq use oil smuggling, kidnapping for ransom, and extortion as sources of revenue (France 24, 2021; UN, 2021; Newlines Institute, 2021). In particular, the oil-rich provinces Diyala, Kirkuk, and Salah al-Din attracted actors involved in the expropriation of oil fields and oil smuggling (R1; Newlines Institute, 2021). The Iranian and Syrian borders, as well as the port of Umm Qasr, as main points of entry for different goods, are focal points for illicit taxation imposed by criminal and terrorist actors (Qaed, 2021; Al-Hashimi, 2020b; Emirates Policy Center, 2021; France 24, 2021). Finally, there are indications that illicit trade in antiquities has continued uninterrupted since the fall of the Caliphate. In conclusion, organized crime in post-Caliphate Iraq has persisted, and in some areas seems to be on the rise. In the following sections, we will discuss the main actors involved in organized crime, before turning to an explanation of the persistence of organized crime using Makarenko’s convergence model.

ISIS remnants’ involvement in organized crime

Following the fall of the Caliphate, ISIS remnants have scattered across Iraq, with Anbar, Salah al-Din, Baghdad, Diyala, Kirkuk, Fallujah, and Ninewa provinces reporting the remnants’ presence, as well as an increased number of terrorist attacks (Institute for Economics and Peace [IEP] 2020; Knights and Almeida, 2020; UN, 2021). In 2020, the UN estimated there were 10,000 active ISIS fighters in Iraq and Syria (UN, 2020a). According to Al-Hashimi (2020a), ISIS remnants have focused on areas in the west bordering Syria, and in the east bordering Iran to secure their revenue streams. The vast region bordering Syria has remained a crucial factor in ISIS’ finances, with ISIS remnants continuing to be engaged with smugglers operating across the Iraq-Syria border, raising over $100,000 a day (UN, 2021: para. 19; Al-Hashimi, 2020b). The Syrian border is also a crucial hub for smuggling fighters and supporters out of Syria to Iraq, mainly from the Al Hawl refugee camp, in cooperation with human smuggling networks (Vianna de Azevedo, 2020).

ISIS remnants earn an estimated $2.5 to $3 million monthly by targeting highways connecting western, northern, and eastern provinces, and imposing taxes on companies in various sectors, including oil transportation, commercial cargo shipping, construction, electric power transmission, telecommunications, and agriculture (Al-Hashimi, 2020a, c). One of the tactics employed by the group is installing fake checkpoints disguised as Iraqi military or PMF checkpoints, and imposing fees for safe passage (UN, 2020b: para. 72). Kidnapping for ransom and extortion of the local population, particularly farmers and shepherds are also reported to continue to be sources of revenue for the group (Martinez, 2020; Al-Hashimi, 2020b; UN, 2021, 2020a; Kittleson, 2021). R3 emphasized how ISIS remnants still rely on transnational criminal networks that have been successfully serving the group for years. As a result, the illicit trade in antiquities continues undisrupted despite the fall of the Caliphate. However, we could not verify this in other sources.

The revenues generated by ISIS remnants since the fall of the Caliphate were and are secured and laundered in several ways. One part of ISIS’ funds is believed to be laundered through investments in real estate (Shaw et al., 2018). ISIS’ investments in legitimate businesses and commercial fronts, including money exchanging companies across Iraq, produce up to $4 million monthly revenues to the group (Al-Hashimi, 2020a; UN, 2020b: para. 13). The group uses a mix of mechanisms for transferring the funds within and out of Iraq and Syria, from legitimate transfers via money exchanging companies, where the front companies established by ISIS play a crucial role, to using hawaladars, or couriers that smuggle the cash across the Iraq-Syria border (UN, 2020b: para. 73; US Treasury Department, 2021). R3 highlighted how some of these hawaladars are Shia Lebanese, affiliated with Hezbollah. This is noteworthy because Hezbollah is allied to Iran and the Syrian Ba’ath regime, which have opposed ISIS. Besides these ‘traditional’ money transferring mechanisms, the group reportedly increasingly relies on cryptocurrencies. The UN Secretary General (UN, 2021) reported increased use of cryptocurrencies in connection with ISIS, although it is emphasized how the use has particularly increased in Syria (not in Iraq).

The PMF’s involvement in organized crime

Since the fall of the Caliphate, it has been increasingly reported how Iran-backed Shia factions that operate outside the government’s control represent a bigger threat to Iraq’s peace and stability than ISIS remnants (Brewster, 2020; Boot, 2020). These groups have been reported to operate like mafia groups or cartels, controlling a myriad of illicit activities across Iraq (Alamuddin, 2019; Pecquet, 2019; Mahmoudi, 2021). Their involvement in illicit business seems to have become prominent after the fall of the Caliphate when the Iraqi state funding for the anti-ISIS military campaign was cut off, and the vacuum left after the fall of the Caliphate provided opportunities for engaging in or expanding organized criminal activities.

The PMF have pervasive control over a significant portion of the Iraqi economy, including airport customs in Baghdad and custom zones across the country, reconstruction projects, oil fields, sewage, water, highways, education, public and private property, tourism sites, and presidential palaces (Newlines Institute, 2021). In addition, the PMF oversee and are directly involved in the transportation of scrap metal, from lands previously controlled by ISIS, turning it into metal, and raising profits estimated amounting to millions of dollars (Davison, 2019). There are reports indicating that PMF factions play a role in sex trafficking (Al-Maghaf, 2019; BBC, 2019; Rached, 2022). The Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (2020) emphasizes how “the Iraqi government did not investigate or hold criminally accountable officials allegedly complicit in sex trafficking crimes or non-compliant militia units affiliated with the PMF”. However, further information about the PMF’s alleged involvement in sex trafficking is lacking.

The PMF filled the vacuum left by ISIS in the Ninewa province and its capital Mosul, a city liberated from ISIS with crucial help from the PMF. The control over Ninewa generates the PMF around $120,000 in revenue monthly – which is not necessarily revenue from organized crime – but also has great strategic value in their aim to increase presence and control in northern Iraq. According to the Newlines Institute (2021), the PMF established control over more than 72 oil fields in the Qayyarah area south of Mosul, previously controlled by ISIS. The oil smuggling, previously managed by ISIS, seems to continue undisrupted under the supervision of the PMF, filling an estimate of 100 tanker trucks of crude oil daily. Besides oil fields in the Ninewa province, the PMF established control over oil fields in various areas across the country, such as the Kirkuk and Diyala provinces (R1).

The PMF, particularly the KH and AAH, concentrated their checkpoints in areas previously controlled by ISIS, and areas that have been ISIS remnants’ strongholds since the fall of the Caliphate (Newlines Institute, 2021). Checkpoints controlling border areas and roads around Baghdad – particularly those part of the international route connecting Baghdad and the provinces of the mid-Euphrates – provide the biggest revenue for the PMF, raising an estimated $100,000 daily from one checkpoint (Newlines Institute, 2021). According to Kahan and Lawlor (2021), Iran-backed PMF factions used the façade of countering ISIS to maintain their presence in strategically important areas, namely the Syrian border and transit routes leading to Baghdad. These areas are crucial for ISIS remnants as transit routes for materiel and personnel, but also as a connection with Baghdad as a crucial recruitment pool and target for terrorist attacks.

The PMF reportedly exercise significant control over areas near the Iraq-Syrian border, where they monopolized the smuggling of fuel, including the alleged selling of Iranian oil to the Syrian regime (Ezzeddine et al., 2019; Khaddour & Hasan, 2020; Mahmoudi, 2021). In addition, based on the available evidence they seem to control most of the drug trade in Iraq, including the smuggling of narcotic pills, originating from Lebanon and trafficked through Syria, and organize distribution of these pills across Iraq, namely in Anbar province (Emirates Policy Center, 2021; Kittleson, 2021). Finally, their control over the border town of Al-Qa’im enables them to smuggle goods, weapons, and their fighters, to fight along Iran-backed forces, into Syria (Adal, 2021). The PMF established control over five official border crossings on the Iranian-Iraqi border, and the port of Umm Qasr, Iraq’s main seaport and primary entry point for goods entering the country (Qaed, 2021; France 24, 2021). It is reported how different types of trade are controlled by different groups. For instance, the cigarette trade is reportedly controlled by KH (France 24, 2021).

Analysis: Persistence of organized crime and crime-terror convergence in post-caliphate Iraq

In post-Caliphate Iraq, organized crime persists, but the fall of the Caliphate has led to a rearrangement of control over illicit markets and organized crime activities. The PMF monopolized control over the main Iraqi ports and all official border crossings on the Iraq-Iran border. These areas serve as smuggling hubs for illicit goods, including drugs, as well as illicit taxation and extortion (Newlines Institute, 2021; France, 24 2021). The Iraq-Syria border and the main roads leading to the capital, Baghdad, are the main areas of competition between the PMF and ISIS remnants, with both actors exercising a significant presence. The border is both the PMF’s and ISIS remnants’ hub for the smuggling of weapons, drugs, oil, and people, while the border areas and roads leading to Baghdad are focal points for illicit taxation imposed by both actors (Newlines Institute, 2021; UN, 2021; Kahan & Lawlor, 2021). We will analyze the persistence of organized crime in post-Caliphate Iraq, applying Makarenko’s model to ISIS and its remnants, and the Iran-backed factions of the PMF, but also look at the relationship between these two main actors in the current organized crime landscape. As noted above, Makarenko’s (2011) idea of convergence covers both the scenarios of integration of a terrorist and a criminal group, and convergence of economic and ideological goals of one entity creating a hybrid criminal-political entity.

ISIS remnants and crime-terror convergence

When it comes to ISIS, from its early beginnings, the organization was involved in organized crime to realize its ambition of establishing an Islamic Caliphate. Long before the seizure of Mosul in 2014, the group acted like a mafia, controlling all economic resources of the Ninewa province, extorting and imposing protection rackets, and blackmailing companies (Schori Liang, 2016). In addition, ISIS recruited fighters with a criminal background.Footnote 11 This phenomenon, often called the “new crime-terror nexus”, refers to the hybridization of criminals and terrorists within the same organization (Basra & Neumann, 2016). Fighters with a criminal background seem to have played an important role in building the Caliphate. They were beneficial for the organization’s organized crime activities, as they were experienced in that domain, but also for terrorist attacks because they already adapted to violence. Such a combination made them more effective fighters (Clarke, 2018). According to Rosas (2020: 62), “ISIS’ connections with the radicalized criminal underworld in Iraq, and control of economic resources resembles the traditional, mafia-style criminal organizations”.

After the proclamation of the Caliphate, the costs of running the proto state increased, and the group diversified its engagement in criminal activities. For trafficking activities, such as illicit trade in antiquities, cooperation with organized criminal networks was crucial in order to keep the funds pouring into the Caliphate. Regarding other illicit sources of revenue, it appears that the group imitated a state and engaged in ‘state-like’ activities, such as oil control and smuggling, and illicit taxation.

When applying Makarenko’s updated crime-terror continuum, ISIS represents an example of both ‘operation’ and ‘organizational’ convergence. First, R3 emphasized how the group formed tactical alliances with criminal organizations, that were crucial for the purpose of trafficking; this is what Makarenko and Mesquita (2014) call operation convergence. In addition, as noted, ISIS recruited fighters with a criminal background. Besides forming alliances, ISIS itself was engaged in criminal activities such as oil smuggling, illicit taxation, extortion, and kidnapping for ransom. ISIS’ ideological goal of establishing the Caliphate was intrinsically linked to the need for funding the proto state, which was done by engaging in a myriad of illicit activities. As a result, the group became so profoundly involved in organized crime, that there was no clear distinction between ideological and economic goals, as they were exhibited simultaneously, reinforcing one another. ISIS thus also reached organizational convergence.

This suggests ISIS evolved into a hybrid criminal-political entity during the Caliphate, and it appears the ISIS remnants can still be qualified as such in the post-Caliphate period. However, it is important to note that the manifestation of the group’s criminal and ideological motivation is not as prominent as during the Caliphate, due to its loss of control over territory and people. Nevertheless, both aspects continue to be exhibited simultaneously, in accordance with their adapted strategy. With the anticipated fall of the Caliphate, the group adapted to a lower-level but still lethal insurgency, reducing the costs needed for larger military operations (Johnston et al., 2019; R2). As discussed above, ISIS remnants persist in securing the funding through illicit activities, showing how their financial and criminal motives were preserved and quickly adapted to new circumstances.

Similarly, according to both R2 and R3, the ideological aspect remains well-preserved, as the base for the attacks and recruitment, using deep-rooted grievances in society to make a mass appeal. According to R2, some governorates that were once ISIS hotspots remain as such, and social media remains an important recruitment and fundraising tool, using the group’s ideology to gain support among local communities. R3 observed how, in terms of collaborations, “ISIS does not care if it is allies or enemies, the money talks louder”. This suggests ISIS’ relation with other actors is not necessarily characterized by competition. This may also indicate that ideology is subsidiary in pursuit of economic goals, however, our respondents indicated it is an equally important part of the group. It can be said that it is just a matter of pragmatism. As pointed out by R3,

ISIS needs money to continue the fight. But there is still the ideology, because ideology sells; crime does not sell. It is basically like this. In order to recruit people, ISIS has leverage with a local population by using ideology. The group needs to stand side by side with local people, and that is why ISIS needs a strong ideology.

This seems to align with Makarenko and Mesquita’s (2014: 260) thesis that terrorist groups that reach organizational convergence, have reached the point where “political (ideological) rhetoric [is used] as a façade for perpetrating [organized crime]”. As we noted above, Makarenko (2004) observed that the continued use of political rhetoric helps terrorist organizations to secure popular support as this rhetoric is used to justify criminal acts. This observation also seems to apply to the case of the ISIS remnants’ use of ideological rhetoric.

Makarenko (2004) holds that in the central point of convergence, ideology and profit are not mutually exclusive, but exist simultaneously. One example of this in the case of Iraq is ISIS’ dependence on “both criminal networks and criminal ‘in-house’ capabilities to fuel its insurgency in Syria and Iraq and to extend its grip far beyond the conflict zone” (Vianna de Azevedo, 2020: 59). By relying on human smuggling networks, ISIS remnants aim to continue the insurgency while staying involved in organized crime at the same time. As emphasized by Rosas (2020: 62), “there is no clear distinction between terrorism and crime in the case of ISIS”.

This exemplifies the fluidity of the crime-terror nexus, with ideological and criminal goals being used interchangeably, adapting to the change of circumstances. The fall of the Caliphate did not end the group’s potent ideology, nor the need to secure funding for its lower-level insurgency through criminal means. For the future, it remains to be seen whether, in the long run, ISIS would be able to preserve the focus on both types of goals in Iraq. However, an absolute change to either economic, or ideological goals, would likely lead to the group’s further demise. Therefore, it is unlikely the group will reach the final, transformational sphere of the updated continuum.

The PMF and crime-terror convergence

When it comes to the PMF, we argued above that the most prominent PMF factions – KH and AAH – can be seen to fall under Richard’s definition of terrorism, and so the question comes up to what extent crime-terror convergence applies to these actors. It should be recalled that the PMF are not as clearly one ‘actor’ or organization as ISIS, considering that the PMF consist of many different groups with at times conflicting ideologies (there are Sunni, Shia and Kurdish factions), and with individual commanders who might act against broader policies of the PMF. However, the PMF factions have been, and continue to be, unified in the fight against ISIS. It appears that the fight against ISIS played a more prominent role in their gaining control over organized crime activities, than their political/ideological orientation, but the political/ideological goals remain important on the longer term, as we will argue.

As emphasized earlier, the classification of the KH and AAH factions as terrorist organizations is complex, as it overlaps with their role of ‘liberators from ISIS’ and their subsequent legitimatization through the integration of the PMF in the Iraqi army. Moreover, their alleged involvement in illicit markets and use of terrorist violence overlap with their post-Caliphate political engagement. As noted above, both groups were founded with strong Shia jihadi, anti-American ideological foundations, and are intrinsically linked to Iran. Besides their Shia ideology, a fundamental difference between ISIS and these groups is their funding. The KH and AAH were first funded by Iran., but after they became integrated into the PMF, the factions started to receive Iraqi state funding for anti-ISIS operation (Reuters, 2020; Rached, 2022; Lane, 2023). The criminalization of their operations became prominent in particular after they lost Iraqi state-sponsorship to fight ISIS following the liberation of Mosul. Consequently, the Iran-backed PMF factions became profoundly involved in organized crime across the whole country, to secure the funding for one of their objectives: spreading Shia/Iranian influence across Iraq.

It is therefore not clear whether the KH and AAH factions within the PMF could be considered ‘hybrid criminal-political entities’ in Makarenko’s terms. One the one hand, following Makarenko and Mesquita’s (2014) model, arguably the KH and AAH factions could be seen to have reached organizational convergence, based on the available information. The scope of Shia, Iran-backed factions’ involvement in organized crime since the fall of the Caliphate, also resembles ISIS’ involvement in these activities during the Caliphate. The similarity is also evident from the fact that the PMF filled the vacuum left by ISIS, by taking over criminal enterprises previously controlled by ISIS. Notably, these factions are still competing with ISIS remnants over strategically important areas such as the Syrian border, and roads leading to Baghdad.

On the other hand, as noted earlier, the ideological aspects of the Shia PMF factions are less pronounced, and the nature and scale of terroristic violence quite different compared to ISIS. While AAH and KH were designated as terrorist organizations by the US, at least for some time they enjoyed a certain level of legitimacy and strong political support in Iraq. AAH and KH, together with the Badr Organization, another Shia PMF faction, formed the Fatah Alliance political party and won 48 parliamentary seats in the elections in 2018 (Countering Extremism Project, n.d.). Despite the dominant ‘liberators from ISIS’ narrative, Iran-backed Shia factions seem to have started to lose local support throughout 2018 and 2019, due to their political and economic expansion, as well as the violence against civilians, which led to protests in Basra, Baghdad and Shia-dominant southern Iraq (Mansour 2019; Alaaldin, 2021; Al-Marashi, 2021). As mentioned above, the 2021 election results also show a decrease in the factions’ public support, with the Sadrists, the PMF’s foremost rival, obtaining 73 seats with the Fatah Alliance getting only 17 (Alaaldin & Felbab-Brown, 2022). However, Iran-backed Shia factions are still deeply entrenched in Iraqi economic, political, and societal spheres (Yuan, 2021). Alaaldin and Felbab-Brown (2022) emphasize how, since the October 2021 elections, Iran-backed Shia factions intensified their political repression and extortion of the local population, particularly in Ninewa and its capital Mosul, and violently oppose attempts of individual PMF fighters to leave the organization.

Moreover, whether the KH and AAH also reached operation convergence remains unclear. No information in the literature indicates tactical alliances transpired between groups like the KH and AAH and organized crime groups. As Omelicheva and Markowitz (2021: 1550) note, such collaboration also is not a given, as “there are considerable barriers to criminal–terrorist cooperation”. Furthermore, state-sponsorship is, or at the least was initially, a central feature of the PMF. This raises doubts on the applicability of Makarenko’s theory, since neither her original nor the adaptation of the crime-terror nexus theory, includes the situation of a hybrid group, that is also simultaneously state-funded. As pointed out by Omelicheva and Markowitz (2021), where the crime-terror nexus literature traditionally perceives involvement in organized crime as an alternative to state sponsorship, there are indications that state-sponsored terrorism and organized crime are increasingly overlapping. We can also see this in the case of Iraq. Possibly, state sponsorship can (partially) fulfil economic goals and does not render Makarenko’s model irrelevant, but it remains unclear to what extent and how state sponsorship factors into and influences convergence. Apart from the financial aspect of state sponsorship, however, as noted above, the case of the PMF shows how state backing can play an important legitimizing role – where ISIS uses ideological propaganda to garner support, the PMF exploit the legitimacy generated by their role as liberators from ISIS. Finally, unlike ISIS, the Iran-backed Shia factions have infiltrated the Iraqi state through politics, which causes an overlap of legitimized and illicit activities. This may warrant an adaptation of Makarenko’s crime-terror continuum. Since the role of state-embedded actors is not addressed in the model, we will explore next how the persistence of organized crime contributes to state fragility, and how state-embedded actors relate to the crime-terror nexus.

The fragile post-caliphate state and the role of state-embedded actors

Considering the findings from this research, it appears that some of the previously discussed symptoms that made Iraq a fragile state – including corruption, sectarianism, and the presence of proxy forces – persist up to this day. Despite the fall of the Caliphate, ISIS as an organization and its ideology were never entirely defeated, and the ISIS remnants continue to act as a hybrid criminal-political entity with both criminal and terrorist goals. Iraq experienced an overall decline in terrorist attacks when compared to the Caliphate era (IEP, 2020). However, ISIS seems to still be responsible for most terrorist activities in Iraq, continuing its operations in rural areas, and its recruitment campaign taking advantage of converging sectarian, political, security, and economic grievances (Al-Hashimi, 2020a; EPIC, 2021; Ezzeddine & Colombo, 2022; IEP, 2022).

The defeat of the Caliphate also came with a cost of increased violence and criminal activities when the Iran-backed factions entered the scene and took control over parts of the country previously held by ISIS. Although the PMF emerged as a key actor to fight ISIS, some of these state-embedded actors started to operate outside Baghdad’s control, pursuing their own political, military, and economic interests (Khaddour & Hasan, 2020). In addition, Iraq continues to be a proxy battlefield, with Iran aiming to increase its influence and infiltrate Iraq’s political, security, economic, and religious spheres (Nada, 2018; Lawlor & Davison, 2020). As noted above, Iran-backed Shia factions are currently seen as an important impediment to Iraqi stability.

Moreover, sectarianism continues, with Shia factions and ISIS remnants competing for power, and fueling tensions between Shia and Sunni communities to gain support (Kahan & Lawlor, 2021). According to Kahan and Lawlor (2021), one of the tactics used by ISIS remnants is stealing PMF uniforms and impersonating factions in attacks, to fuel local resentment and reduce the local population’s willingness to cooperate with the PMF. Also, the inability of non-PMF Iraqi security forces to protect Sunnis from the factions’ abuses, and the factions’ ability to operate with impunity due to powerful political connections, is believed to further deepen Sunnis’ mistrust and increase the likelihood of support for ISIS. In addition, despite the government’s attempts to tackle corruption, it remains rampant in post-Caliphate Iraq (R1). According to Mansour (2021: 29), the Iraqi government “expects to make $9 billion from customs each year, but at most, $1 billion finds its way into government coffers”. The rest is shared within the “collusion between officials, political parties, gangs, and corrupt businessmen” (France 24, 2021). Rampant corruption is the main facilitator of these activities, enabling Iran-backed Shia factions to operate with impunity.

In light of these observations, it appears that Iraq persists as a fragile state, with the power and security vacuum attracting different entities that have taken over control of substantial parts and important infrastructure of the state, arguably rendering it a ‘black hole state’. Aside from terrorist activity, the power and security vacuum transformed the country into a criminal battleground, with ISIS remnants and the PMF fighting to establish control over the most lucrative parts of Iraq, borders, ports, and Baghdad with its surrounding transit roads, with the state exercising minimal or no control over these areas. These actors may have no interest in a stable state since a fragile state offers more room for criminal and terrorist activities to continue undisrupted. Here, we recognize Felbab-Brown’s (2019) abovementioned point on crime as a method of governance.

Regarding the role of state-embedded actors in the crime-terror nexus, post-Caliphate Iraq is an interesting example to be examined. The most prominent Shia factions under the PMF are part of a state apparatus and operate in a grey area between non-state actors, and the formal government. In contrast to ISIS, who never had political influence on the Iraqi state apparatus, AAH and KH have both de facto and de jure recognition and governance, which provides a certain level of legitimacy, and accommodates crime-terror convergence. In that context, Omelicheva and Markowitz (2021: 1553) emphasize how state weakness can be a consequence of purposive efforts by parts of the state apparatus, using control over coercive and other state institutions to undermine an adversary and generate rents. In addition, the infiltration of Shia factions in the Iraqi state apparatus undermines the remaining aspects of political and security apparatus, which in combination with sectarianist competition may strengthen ISIS remnants’ position and facilitate their continued existence. The fragile Iraqi state thus not only facilitates crime-terror convergence, but parts of the state apparatus control and form an actual part of the crime-terror nexus.

The Iran-backed PMF factions do not have unlimited leeway, however. In July 2019, Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi issued a decree, ordering the full integration of the PMF factions into state security forces. The decree includes an order to the PMF factions to close their headquarters, economic offices, and checkpoints (Mamouri, 2019a; Knights, 2019). KH, in particular, expressed discontent with the decree, while AAH as well as the PMF’s strongest opponent, a prominent Shiite cleric Muqtada al-Sad, leader of the Sadrist Movement and Saraya al-Salam, supported it (Mamouri 2019a, b). Despite the decree, the Iraqi government faces a persistent challenge in taking control over some of the factions and their activities, with the PMF economic offices, checkpoints, and bases still operating across the country (Mamouri, 2019b; Azizi, 2021; Alaaldin & Felbab-Brown, 2022).

Following the fall of the Caliphate, the competition for control over businesses and checkpoints, as well as the quest for power, legitimacy, and votes, caused fragmentation between some of the PMF factions (Mansour, 2019; Al-Marashi, 2021; Ezzeddine & Van Veen, 2021; Alaaldin & Felbab-Brown, 2022). The assassination of the PMF commander Abu Mahdi al-Muhandi in 2020 furthered disagreements between dominant factions, Badr, AAH, and Saraya al-Salam on the one hand, and KH on the other (Al-Marashi, 2021; Ezzeddine & Van Veen, 2021; Karriti, 2021). Knights et al. (2021b: 9) emphasize how there is an increase in “competition rather than coordination” between AAH and KH. Both factions openly criticize each other’s resistance efforts through various media channels (see Malik, 2021a, b). Finally, post-Caliphate PMF fragmentation has been deepened by the withdrawal of the Atabat – Shia factions affiliated with the highest Shia authority in Iraq, Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani – from the PMF, and their integration into the Iraqi Army and Ministry of Defense structures (Alaaldin, 2021; Ezzeddine & Van Veen, 2021).

Conclusion and discussion

In this contribution, we have applied Makarenko’s (2004, 2011) and Makarenko and Mesquita’s (2014) theoretical work on convergence to the case of post-Caliphate Iraq. The article is the result of a qualitative, mixed-methods case study, combining an extensive literature review of academic articles, books, policy briefs, NGO and think-tank reports, with three expert interviews. Our case study shows that the vacuum caused by the fall of the Caliphate resulted in persistence and growth of organized crime. The available evidence suggests that this led to fierce competition and a rearrangement of control over organized crime activities. Remnants of ISIS have scattered across Iraq but remain in control of parts of ISIS’ previous criminal enterprise, continuing to generate revenue through smuggling, illicit taxation, and kidnapping for ransom and extortion of the local population. Especially Iran-backed Shia factions of the PMF took over ISIS’ criminal enterprise in liberated areas and monopolized control over the main Iraqi ports and all official border crossings on the Iraq-Iran border. These areas serve as smuggling hubs for illicit goods, including drugs, as well as illicit taxation and extortion. The Iraq-Syria border and the main roads leading to the capital, Baghdad, are the main areas of competition between the PMF and ISIS remnants, with both actors exercising a significant presence.

When applying the framework on convergence, we conclude that while the ISIS remnants can be characterized as hybrid criminal-political entity, Makarenko’s framework fits less with the Iran-backed Shia PMF factions. On the one hand, both for ISIS remnants and the Shia PMF factions, involvement in organized crime generates funds to continue their operations. In their competition for power, both actors have been purposively exploiting social-political-economic vulnerabilities to garner support among local communities: where ISIS seems to have used ideological propaganda as a façade for its involvement in illicit trade and base for attacks and recruitment, the Iran-backed groups have exploited the legitimacy generated by their role as liberators from ISIS and by their integration in the Iraqi state apparatus. The interaction between ideological-political and economic motivations contribute to keeping the Iraqi state fragile as both actors pursue their own interests. As Makarenko’s convergence model helps to focus on this interaction, it is beneficial in understanding the evolution of terrorist and criminal actors, and thus the persistence of organized crime, in post-Caliphate Iraq.

At the same time, our case study raises several questions on the applicability and utility of the convergence model, as well as the ‘criminal’ and ‘terrorist’ concepts in this case. First, the assumption underlying a conceptual convergence model such as Makarenko’s is that actors can initially be characterized as (purely) ‘criminal’ or ‘terrorist’. Where ISIS has displayed both terrorist and organized crime activities from its start, the Iran-backed PMF factions in their early days can be best characterized as a state-funded armed actor with a political, more than an ideological agenda. As we noted, while they meet Richards’ definition of terrorism, they perhaps share more similarities with the Afghan warlords than with a terrorist organization such as ISIS. On the other hand, ISIS remnants resemble other potent terrorist organizations, such as Boko Haram, who exploit local and regional dynamics for criminal and terrorist activities (Omelicheva & Markowitz, 2021). Second, the role of state sponsorship and state-embeddedness, which is of particular relevance in the case of the Iran-backed PMF factions, is not part of Makarenko’s convergence model. The fact that the PMF are state-embedded complicates drawing the line between ‘licit’ an ‘illicit’ activity: if an actor carries out tasks on behalf of the state in controlling borders and trade, is it not reasonable – to some extent – if it generates revenue through taxation? Of course, such an argument can by no means justify the extensive involvement of the PMF in a wide variety of criminal activity that the available evidence suggests.

While Makarenko’s model represents a development in understanding the complex nature of the crime-terror nexus, the model is still an implicit dichotomy, as the precondition for its successful application is to label a group as either criminal or terrorist. Therefore, it leaves no room for different types of hybrid actors – those heavily embedded in legitimate state structures - as seen in this study. Since the nature and manifestation of the nexus is intrinsically linked to the nature and degree of state involvement, as emphasized by Omelicheva and Markowitz (2019), state-embedded actors should be a focal point of the model. By developing the model around different roles of the state, there would be, at least, a clear distinction between entities without legitimate state connections, and state-embedded actors, making the model more applicable to the situation on the ground. Such a conceptualization would move a current understanding of the roles of the state beyond a weak or fragile state as a necessary precondition of the crime-terror nexus. Moreover, the inclusion of different roles of the state in the model could make the demarcation between state funding and revenues from organized crime clearer, as so far, the crime-terror nexus literature understood organized crime as an alternative to state funding, while the case of Iraq showed that these revenue streams are not mutually exclusive.

While our study fills a gap in the existing academic literature by outlining and explaining the persistence of organized crime in the post-Caliphate Iraq, the complexity of the post-Caliphate environment calls for further research. Further research is needed to expand the existing crime-terror nexus theory and unravel the different roles of the state, including state-sponsorship, and their impact on crime-terror nexus dynamics. Additionally, the pragmatism of terrorist organizations with such a potent ideological reputation as ISIS, operating in a country with a deep sectarian division like Iraq, deserves more attention.

As the fight against ISIS persists and the influence of Shia factions, thus Iran, is strong, the burden on the already fragile Iraqi state is increasing. At the same time, we also noted that the Iran-backed Shia factions do not have unlimited leeway. It remains to be seen whether the increased competition will further divide Iran-backed Shia factions or bring them closer, opening new possibilities for (political) collaboration. Also, the formation of the new government, in a large part consisting of PMF opponents, and the factions’ internal dynamics, raise the question of how these developments will impact the factions’ overlapping legal and illegal economic activities across the country. It also remains to be seen how the competition for power over the Iraqi state apparatus will affect the position of the ISIS remnants, and whether they will be able to exploit another opportunity to resurge in Iraq and Syria. The outcome of the struggle for power will determine if Iraq is at the brink of another turning point, or if the status quo will be consolidated.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

Briefly after 9/11, the UN Security Council, in Paragraph 4 of its Resolution 1373 (28 September 2001), “Note[d] with concern the close connection between international terrorism and transnational organized crime, illicit drugs, money-laundering, illegal arms-trafficking […]”.

After the declaration of the Caliphate in June 2014, the group shortened its name to ‘Islamic State’ (IS) to reflect its expansionist ambitions (Irshaid, 2015). Throughout the literature, different names occur for the same group, such as ISIS, IS, ISIL, or Da’esh. For the purpose of this study, the term ISIS will be used.

We use the term ‘post-Caliphate Iraq’ in this study to refer to the period since 9 December 2017, when Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al Abadi proclaimed military victory over ISIS. Nevertheless, it was not until 23 March 2019 that the ISIS Caliphate formally ended with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) capturing Baghouz, the last portion of ISIS-controlled territory.

A state is considered weak or fragile when it “[…] struggles to fulfil the fundamental security, political, economic, and social functions that have come to be associated with sovereign statehood” (Patrick, 2011). A state is considered failed when there is “a prolonged violence, directed against the existing government or regime, and the inflamed character of the political or geographical demands for shared power or autonomy that rationalize or justify that violence in the minds of the main insurgents” (Rotberg, 2004: 5).

State-embedded actors are “criminal actors that are embedded in, and act from within, the state’s apparatus, including officials from state institutions, such as law enforcement bodies and the judiciary” (Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, 2021: 23).

We acknowledge that there are other militia groups, not connected to the PMF and/or Iran, operating across the country. They include, for example, Saraya al-Salam (also known as Peace Brigades), a strong opponent of the PMF. However, while acknowledging they are not the only relevant actor, this article focuses on the PMF as they emerged as the most prominent actor in the fight against ISIS and replaced most of ISIS’ criminal enterprise.

Mowaffak al-Rubaie, an Iraqi politician and national security advisor (2004–2009) emphasized how “[…] It took the US three months to start bombing ISIS in Iraq, while it took 24 hours for Iran to send truckloads of arms and people coming to help us defending Baghdad. We did not have any other option than turn to Iran.” (VICE News [YouTube] 2020).

In this article, the term PMF refers mainly to Iran-backed Shia factions within the PMF, operating outside the Iraqi government’s control, with the most prominent ones being Kata’ib Hezbollah and Asaib Ahl al-Haq. The umbrella term ‘PMF’ covers more factions which are not all necessarily involved in organized crime.

Christian Vianna De Azevedo, Webinar “Iraq’s New Cycle of Radicalization; Cause for Alarm?”, 16 March 2021.

References

Abu Zeed, A. (2020). Drug smuggling, abuse on the rise in Iraq. Al Monitor: The Pulse of the Middle East. Al-Monitor. https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2020/11/iraq-security-drug-crystal-iran.html. Accessed 20 January 2022.

Adal, L. (2021). Organized crime in the Levant: Conflict, transactional relationships and identity dynamics. Global Initiative. https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/organized-crime-levant. Accessed 20 January 2022.

Al-Hashimi, H. (2020a). ISIS in Iraq: From abandoned villages to the cities. Newlines Institute. https://newlinesinstitute.org/isis/isis-in-iraq-from-abandoned-villages-to-the-cities/. Accessed 20 January 2022.

Al-Hashimi, H. (2020b). ISIS on the Iraqi-Syrian border: Thriving smuggling networks. Newlines Institute. https://newlinesinstitute.org/isis/isis-on-the-iraqi-syrian-border-thriving-smuggling-networks/. Accessed 20 January 2022.

Al-Hashimi, H. (2020c). ISIS Thrives in Iraq’s ‘money and death’ triangle. Newlines Institute. https://newlinesinstitute.org/isis/isis-thrives-in-iraqs-money-and-death-triangle/. Accessed 20 January 2022.

Al-Maghaf, N. (2019, October 6). In Iraq, religious ‘pleasure marriages’ are a front for child prostitution. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/06/pleasure-marriages-iraq-baghdad-bbc-investigation-child-prostitution. Accessed 20 January 2022.

Al-Marashi, I. (2021). Iraq’s popular mobilisation units: Intra-sectarian rivalry and arab shi’a mobilisation from the 2003 invasion to Covid-19 pandemic. International Politics, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-021-00321-4.

Al-Rabehi, A., & Al-Nasseri, H. (2019). Sex trafficking: Baghdad’s underground vestibules. Network of Iraqi Reporters for Investigative Journalism [NIRIJ]. https://nirij.org/en/2019/03/22/sex-trafficking-baghdads-underground-vestibules/. Accessed 20 January 2022.

Alaaldin, R. (2021). Muqtada al-Sadr’s problematic victory and the future of Iraq. Brookings. Muqtada al-Sadr’s problematic victory and the future of Iraq. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/10/28/muqtada-al-sadrs-problematic-victory-and-the-future-of-iraq/. Accessed 20 March 2022.

Alaaldin, R. (2020, February 29). What will happen to Iraqi Shiite militias after one key leader’s death? Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/02/29/what-will-happen-iraqi-shiite-militias-after-one-key-leaders-death/. Accessed 20 January 2022.

Alaaldin, R., & Felbab-Brown, V. (2022). New vulnerabilities for Iraq’s resilient Popular Mobilization Forces. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2022/02/03/new-vulnerabilities-for-iraqs-resilient-popular-mobilization-forces/. Accessed 20 March 2022.

Alamuddin, B. (2019, August 25). Mafia militias in Iraq reopen Pandora’s box. Arab News. https://www.arabnews.com/node/1545121. Accessed 20 January 2022.

Arraf, J., & Schmitt, E. (2021, June 4). Iran’s proxies in Iraq threaten U.S. with more sophisticated weapons. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/04/world/middleeast/iran-drones-iraq.html. Accessed 20 January 2022.