Abstract

Following major criminal cases in the food system, such as the Horsemeat and fipronil egg scandals, the phenomenon of food fraud has emerged as a priority concern for supranational (e.g. European Union) and domestic policymakers and regulatory authorities. Alongside this, there is increasing interest from academics working in both the natural and social sciences (but rarely together), where we see common and overlapping objectives but varied discourses and orientations. Consequently, various framings about the nature, organisation and control of food fraud have emerged, but it is not always clear which of these are more reflective of actual food fraud realities. This article analyses three key areas in the literature on food fraud where we see fault lines emerging: 1. food fraud research orientations; 2. food fraud detection and prevention (and the dehumanisation and decontextualisation associated with analytical testing); and, 3. food fraud regulation and criminalisation. We argue that these fault lines raise questions over the plausibility of knowledge on food frauds and in some cases produce specious arguments. This is significant for food fraud policy, strategy and operation, in particular in terms of how we generate expectations about the actual realities of food fraud and corresponding actions that are realised, and make knowledge practically adequate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As a policy and social scientific construct, food fraud has in recent years gained momentum as a major global issue. This is primarily due to a series of major cases and scandals, such as the adulteration of beef products with horsemeat that came to light in 2013, the fipronil in eggs scandal that emerged in 2017, or the slaughter of sick cows for human consumption in 2019, all within the European Union (EU), and the need to ‘do something about it’. Consequently, the phenomenon of food fraud has emerged as a priority concern for supranational (e.g. EU) and domestic policymakers and regulatory authorities. Alongside this policy concern, there is increasing interest from academics working in the natural and social sciences (but rarely together) with research driven by their varying conceptual and theoretical (and sometimes commercial) agendas or intentions, resulting in conversations with themselves or those who are like-minded. For instance, amongst others, criminologists, sociologists and socio-legal scholars foreground the making of food fraud rules, how and why such rules are broken, and the public–private responses to the breaking of these rules. Biological scientists and biotechnologists focus on food authenticity and identifying discrepancies in the DNA of foodstuffs that might indicate frauds have taken place. Business and management scholars examine the integrity of food supply chains and processes, and the security of foods within trading networks, and improving resilience to frauds. Within such scholarship, we see common and overlapping objectives, such as the need to reduce or prevent food frauds, but varied narratives and framings about the nature, organisation and public/private control of food fraud have emerged within science (and policy), but it is not always clear which of these are more plausible reflections of food fraud realities than others, and in some cases fault lines are appearing that undermine what we know about food frauds (and how we know it) that can lead to specious or (intrinsically and/or extrinsically) political claims.

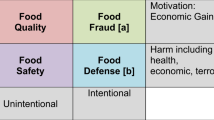

Unconnected scientific conversations are partly responsible, but also a symptom of disciplinary disjunctures, yet at the centre of all these agendas is an objective recognition of food frauds as criminal and/or non-compliant behaviours (although the foregrounding of different concepts e.g. food fraud, food defence, food safety inevitably implies the posing of different research questions (see [1]). But how do varied disciplinary or policy accounts reflect food fraud realities? Which representations of food fraud and its control are more adequate than others, on the basis that they explain more of the phenomenon under study? One approach is to scrutinise the plausibility and practical adequacy of the knowledge produced. All knowledge is fallible and the open system nature of the social world makes redundant attempts to establish absolute truths about particular crimes and criminal phenomena. So thinking in terms of how useful particular knowledge is, in terms of how food frauds and its control are understood, and reflecting on the research framings, orientations and methodological approaches utilised to generate this knowledge, can assist in directing us towards which knowledge is more useful in any given context, such as for enforcement or regulatory interventions.

As Sayer [2: 69] explains, [t]o be practically adequate, knowledge must generate expectations about the world and about the results of our actions which are actually realized’. In line with this, ‘[t]he aim of critical criminology is in part to assess the practical adequacy or objectivity of different social constructions and this task assumes a degree of objectivity of the social phenomenon in question’ [3: 346].Footnote 1 Consequently, in terms of internal validity, to what extent do varying accounts of food fraud provide epistemic gain and is such knowledge a plausible account of reality within the contexts analysed that can inform practice, making sense to the context from which it is drawn and to the individuals (e.g. enforcement/regulatory actors) that operate there? In other words, by plausibility, we consider the ways in which the orientations and methods pursued, often as a reflection of disciplinary intentions, produce knowledge that simply reflects the chosen method and focus, or whether it reflects the reality of food frauds. In terms of practical adequacy, we consider whether the knowledge that is produced is useful for particular purposes, such as food fraud detection, prevention or control.

In line with the above, this article analyses three key issues (not an exhaustive list) in the literature on food fraud where we see fault lines emerging in relation to the knowledge produced. We focus primarily on the UK context, but the arguments have relevance to the EU more widely and beyond. First, we analyse orientations in food fraud research, arguing for greater reflexivity in methodologies and conceptual frameworks to reduce the likelihood of research findings being an artefact of the methods and data used, rather than reflecting the reality of food frauds. Here, we also examine food fraud framings, and specifically the depiction of the extent of food frauds as episodic and exceptional, arguing for the need to incorporate the routine and mundane frauds within business, and dive deeper into the underlying generators of such frauds. Second, we consider food fraud detection and prevention, and the foregrounding of analytical testing as the solution, arguing that this dehumanises and decontextualises social and situated fraudulent actions, and has limited applicability. Third, we focus on the tensions inherent in the regulation and criminalisation of food frauds. We do not offer a comprehensive or exhaustive examination of all areas of contention, but drill down into specific issues that we consider to be of significance. There is also overlap between the three sets of fault lines we discuss. However, we argue that these fault lines raise questions over the plausibility of knowledge on food frauds and in some cases produce specious arguments. This is significant also for food fraud policy, strategy and operation, in particular in terms of how we generate expectations about the actual realities of food fraud and corresponding actions that are realised, and make knowledge practically adequate.

Fault lines in research orientations

In relation to the discipline of criminology, Cohen [7: ix] argued there are three orders of reality. First, the object of study, or the ‘thing’ itself, that is, crime and the apparatus for its control—in this case, ‘food fraud’. Second, research and speculation about this thing, that is, how we describe, classify, theorise, explain and develop normative and technical solutions to crime (or ‘food fraud’) as a ‘problem’. Third, reflection about the nature of the whole enterprise itself. Thinking in terms of the interplay between these three levels of reality allows us to critically reflect on the food fraud literature and assess what we know, think we know (based on the methods we use), and/or need to know, about the nature, extent and control of food frauds.

The research literature on food fraud is sparse when compared to other types of fraud (e.g. credit card frauds, corporate frauds, investment frauds, and other ‘organised frauds’) though fraud research generally also remains at the margins of academic and criminological inquiry when contrasted with the analyses of varied volume crimes, such as anti-social behaviours, property crime or interpersonal violence, or even serious and organised crimes. For instance, a search for articles on varied frauds published in Crime, Law and Social Change indicates that four have been published on ‘food fraud’ (two of which involve the current authors), 30 on ‘credit card fraud’, 23 on ‘corporate fraud’, and 16 on ‘investment fraud’, with 41 on ‘anti-social behaviour’, 40 on ‘interpersonal violence’ and 157 on ‘property crime’.Footnote 2 This is a crude and superficial analysis, but indicative of the academic attention devoted to food frauds in a journal with a strong reputation for publishing related research.

This lack of attention reflects (at least) three issues: first, a lack of, or ambiguous, ownership of food fraud cases and enforcement as regulatory fragmentation leads to disinterest or inabilities (due to resource and prioritisation) in taking on food fraud cases, despite emerging policy narratives reinforcing the market and consumer harms of such frauds (although deaths are rare); that, second, leads to reduced (or narrowly targeted) funding for research aiming to analyse the actual nature and underlying generative and real causes of fraud within the food system; and, third, the research difficulties in accessing food fraud networks as whoever is involved in the frauds, from seemingly legitimate food system businesses to entirely illegitimate organised crime groups, and all those in-between, do not generally permit access to outsiders such as researchers. These methodological and data issues are part of the reason for variably plausible accounts of food fraud as they reduce the valid data available on the motivations and drivers of those actors, who either in a pre-planned manner or more reactively, are able to visualise and capitalise on opportunities for fraud. Similarly, measuring the extent of food fraud is notoriously problematic due to a lack of authoritative data and methods with which to measure fraud across sectors and jurisdictions. Estimates of global trade in counterfeit food and drink range from $6.2bn to $40bn [8: 1]. But these estimates have little meaning given the difficulties in quantifying the extent of food frauds, but also do not include the costs of enforcement, the costs to businesses in improving their compliance systems, or the costs of changes in consumer behaviours.

The aforementioned concerns lead to a first fault line. Due to the above limitations, depictions of food fraud and ‘food fraudsters’ in the academic and policy literature (and media) is mostly reliant on known cases that have come to the attention of domestic (e.g. the UK’s National Food Crime Unit) or regional (e.g. EU Food Fraud Network, the EU’s Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF), or EUROPOL’s OPSON reports) enforcement actors. Whilst known cases can be an appropriate analytical starting point for understanding the nature and organisation of particular offences, using such data (even if caveats are recognised) to develop representative accounts (e.g., patterns and trends of fraud) is beset with limitations as our understandings begin to reflect the activities and agendas of enforcement rather than the realities of the phenomena. As Gussow [9] evidences, the willingness and abilities of enforcement agencies dictate which food frauds are discovered.

In research terms, this means there is a major absence of systematic and robust empirical investigation into the nature of food frauds, their victims and harms, with studies unable to plausibly instantiate theories and typologies of the ‘food fraudster’ beyond offering abstract propositions (that may be valid but not empirically robust). Consequently, many academic studies draw on anecdotal evidence of individual cases, or rely on enforcement data, to put forward concepts and explanations of such offending, and in turn advocate control and policy solutions (including our own earlier work). For instance, studies have analysed reported cases over time to identify trends and patterns of food fraud offending types, leading to conclusions about certain types being more prevalent than others and such findings seemingly providing an evidence-base for targeted interventions and future scientific research. But in line with Cohen’s [7] observations, such accounts are artefacts of the data and methods used, leading to constructions of the ‘thing’ to be a product of the research, rather than a reflection of reality. These accounts may of course be accurate, but the lack of rigorous data undermines their practical use and reflects an inherently flawed logic, and the implications for control responses and research funding calls are clear as resources may be misdirected.

New and varied data are needed to inform our undertanding of food fraud. The absence of such data in part reflects the relatively new scientific interest in the topic and as such the rich, in-depth qualitative and ethnographic accounts of offending, or the large-N quantitative self-report and victimisation surveys that we see with other areas of crime have not yet emerged. However, there are notable examples that do develop new social scientific quantitative and qualitative data on food crimes and food fraud where the findings and insights reflect the methods used. For example, van Ruth et al. [10], drawing on the routine activities theory informed SSAFE food fraud vulnerability assessment tool,Footnote 3 interviewed actors from food sector businesses to gain insight into the drivers and enablers of fraud in varied supply chains; Yang et al. [11, 12] undertook interviews and a survey, again drawing on the SSAFE tool, to assess fraud vulnerabilities to the milk supply chain in the Netherlands and China as perceived by industry actors, Kendall et al. [13] use focus groups with middle-class Chinese consumers to understand attitudes, perceptions and beahvioural responses towards food fraud. These studies also represent rare examples of integrative and collaborative research teams from the social and nature sciences to make sense of the multi-dimenstionality at play in particular food fraud related phenomena.

In line with Cohen, more reflection on the process of food fraud research and subsequent accounts would offer a more critical and plausible take on what we know about food fraud and why certain agendas and approaches that construct the nature of the food fraud problem can be more a product of the research process and the intrinsic politics of disciplines. This is necessary for both analytical reasons, that is, developing multi-faceted and reflexive accounts of food fraud realities and practical reasons, that is, informing enforcement, regulatory and business compliance responses.

Following on from this, a second fault line relates to the focus of inquiry in food fraud research as weak empirical data or policy/enforcement constructions in turn drive subsequent research and corresponding framings. With this in mind, academic scholarship tends to focus food fraud research in two ways; 1. towards food fraud ‘acts’; and 2. towards food fraud ‘actors’. Table 1 outlines the features of these foci of inquiry in food fraud research as based on our understanding of the field. In essence, these varying foci are coterminous, in that the ‘thing’ under study relates to ‘the abuse or misuse of an otherwise legitimate business transaction and an otherwise legitimate social/economic relationship in the food system in which one or more actors undertake acts or omissions of deception or dishonesty to avoid legally prescribed procedures (process) with the intent to gain personal or organizational advantage or cause loss/harm (outcome)’ [14: 611]. Although separated here, both foci can be integrated in research and can offer rich insights into particular manifestations of food frauds and of those involved but within each research orientation, significant disjunctures have emerged, and this has implications for how we understand the reality of the nature of food frauds. In both cases, research might be driven by concerns with particular food fraud targets (e.g., very specific foodstuffs and products) and industries (e.g., red meat or fish) but with little systematic evidence (or intelligence) as to why such targets have been selected.

Food fraud acts and harms

In terms of a focus on specific ‘acts’ of food fraud and their associated harms, concern lies with the nature of the act (or omission), the characteristics of the fraudulent methods and the defining features of the particular behaviours. These acts are usually in line with state defined violations of criminal and regulatory laws, such as intentional frauds or other food laws (see [15], for an overview of food fraud legal frameworks in the UK and EU). That said, attempts have also been made to broaden scope away from legal violations to a focus on harmful acts to incorporate breaches of morality and ethics (see [16: 12]) where we see focus also on those ‘lawful but awful’ [17] behaviours of corporate elites such as misleading food packaging, contributing to widespread obesity, or food poisoning (see [18: 41–45]). In research terms, ambiguity in relation to legal status ought to be embraced as the ‘problem’ of food fraud cannot be ‘solved’ through attempted categorisation as ‘crime’ or ‘not crime’, as the areas of contestation and controversy makes them sociologically of interest. Whether social scientists frame their focus of inquiry in terms of narrow, legalistic definitions of food fraud, or broaden their focus to also incorporate varied harmful behaviours, it is vital in either case that clear conceptual parameters for their research orientations are developed. ‘Food fraud’ is in some ways a ‘chaotic conception’, or ‘bad abstraction’ (see [2: 138–139]), in that ‘it’ integrates together unrelated and inessential objects and relations, for example, assuming that those involved in the adulteration of foodstuffs behave similarly to those involved in the counterfeiting of alcohol, and this creates issues for explaining and responding to such activities. We see this with predominant policy conceptions that explain varied food frauds almost always as being economically motivated, which neglects the social complexity of human behaviours [14]. Thus, researchers must ensure their concepts reflect objects and relations of study that are internally related in order for their research to be clear and meaningful.Footnote 4

Integrating the sensational with the mundane

Food frauds usually come to public attention, often in the news media, as sensational, exceptional, or ‘newsworthy’ events that are damaging to consumers, other businesses, and the wider public. Prominent examples have included the 2008 melamine milk scandal in China that resulted in six deaths and 50,000 hospitalisations. More recently, cases such as the 2019 slaughter of sick cows in Poland have brought into question governments’ abilities regarding traceability of food supply networks, and generated significant public and academic attention on the way in which food products are sourced, handled, and overseen. While these exceptional events are important in their own right, they tend to be associated with somewhat haphazard and reactive policy responses that are not necessarily implemented effectively in order to reduce vulnerability to food frauds. For instance, the UK National Food Crime Unit (NFCU) was established in 2015 largely as a consequence of the 2013 European horse meat incident, yet such regulatory agencies are typically under-resourced and part of a more complex and fragmented enforcement context [8: 4]. In consequence, the rhetoric and high profile of exceptional events have the potential to influence food fraud policy, and in turn direct scientific research in a ‘knee-jerk’ reaction way that has not necessarily considered the nature and extent of the full range of frauds that occur across societies.

Policy and research accounts of food fraud must be wary of framing and portraying food fraud acts as exceptional and episodic events that are detached from otherwise licit, functional, and unproblematic market or business processes. This obscures routine and mundane frauds generated by the structure and dynamics of the food system and market [14, 19, 20]. The extent and scale of food frauds are not binary issues, as related behaviours exist on spectrums of greater or lesser frequency, and greater or lesser severity and harm. Foregrounding of the exceptional and episodic, whether in the media, policy or research, is problematic as it normalises routine frauds that are considered not to be ‘newsworthy’ or deserving of policy attention due to their less severe or prominent nature and ensures policy, in the UK specifically, continues to foreground concepts of food safety and food authenticity [21]. We see this elsewhere, for instance, where concerns over adulterated avocado oils in the US [22], non-compliant raw drinking milk suppliers in New Zealand [23] and the closing of fraudulent ketchup factories by the Punjab Food Authority [24], receive notably less media or policy attention when compared to scandals such as the 2013 European horse meat incident. When taken as separate events, this inconsistent attention is perhaps understandable, since some individual cases will inevitably be more ‘newsworthy’ than others due to factors such as who the victims are, the severity of consequences or how widespread the fraud was, both in terms of geographic scope and number of actors involved. However, this attention on sensationalist cases risks detaching individual cases from the standard, routine business processes within which they occur.

Focusing on routine and embedded instances of food fraud is important in order to understand the full scope of underpinning processes that occur within the spheres of business, industry, regulation, and policy-making. van Ruth et al. [25] outline key factors associated with food fraud vulnerability in licit markets, including opportunities, motivations, and control measures, which intersect with standard business practices including opportunities (both technical and in time and space), economic drivers, culture and behaviour, as well as technical and managerial control measures. An analysis of the Spanish olive oil market by Lord et al. [26] showed that understanding situational actions in conjunction with ‘entrepreneurial’ activity can be an important cornerstone of preventing and tackling food fraud that is embedded within business structures. In addition, if left unchecked, routine food frauds could become more frequent or severe in the event of limited accountability, which highlights the importance of ensuring that mundane cases are given sufficient attention. The desire by researchers, industry and policy makers to appear to be taking action against sensational events ultimately serves to obscure embedded practices within industry that also warrant attention. The key concern is that the drift towards the exceptional, sensational and episodic depicts an unbalanced account of the reality of food frauds, and downplays the complexity that underpins the occurrence of food frauds, and both these issues in turn undermine the practical adequacy of knowledge that is produced for increasing understanding and informing policy and enforcement.

Food fraud actors

In terms of a focus on the ‘actors’ involved in food frauds, studies in this orientation foreground the characteristics of the actors involved in the offending, seeking to highlight distinctive features such as part of an ‘organised crime group’, or business ‘rogues’ (usually individuals). For example, Elliott [27: 6] concluded in his review of the integrity of supply networks that ‘[f]ood fraud becomes food crime when it no longer involves a few random acts by ‘rogues’ within the food industry but becomes an organised activity perpetrated by groups who knowingly set out to deceive and or injure those purchasing a food product’. He goes on further to state ‘[b]ut the serious end of food fraud is organised crime, and the profits can be substantial’ [27: 12]. This framing is problematic for two main reasons. First, it implies food frauds are predominantly carried out by individual actors, whether people or businesses, and whether internal industry actors or external ‘organised crime groups’, downplays the organised deviant activities of large corporate players within the food system, in some cases with the collusion of the state (see [20, 28]), and the market dysfunctionality that creates opportunities for fraud across and within food networks and trading relations (see [14]). Second, it suggests food frauds are random and in some way episodic and exceptional (see above), rather than sustained and embedded practices within the food industry that are harmful in the aggregate. One key issue is that whoever becomes involved in the frauds, a necessary aspect of all cases is involvement in some form of legitimate business environments and transactions, hence more can be gained from analysing food fraud as an endogenous phenomenon of the food system [14]. In addition, Gussow [9] argues that motives and gains are often misleadingly conflated. In other words, actors’ intentions and motivations are often reduced to simplistic economic rationality, neglecting the diversity of incentives that offenders might encounter, and in turn producing unsophisticated successionist accounts of what motivates food fraud offenders, and this undermines the practical adequacy of reductionist accounts.

Integrating agency and structure through the lens of the market

One further issue that arises from the individualisation of food fraud offenders is that regulatory approaches target potential actors instead of focusing on the structural conditions—market structure, complexity of supply chains, contractual arrangements—that create ready-made structures for the commission of crimes in the system. A consequence of individualising food frauds, or embedding strategic responses within the policy discourse of ‘serious and organised crime’, is the perceived necessity by states to criminalise responses at the level of these individual events rather than address the real, deeper mechanisms that enable such crimes to occur. It may also be effective to develop systematic assessments such as script analysis, to identify the particular antecedents and factors that come together to enable frauds to take place, and situational prevention, in order to reduce vulnerability to food fraud in the short term (see [26]). These assessments would enhance opportunities for researchers, industry practitioners, and policy makers to proactively try to prevent food fraud from occurring in the first place.

The key issue is that individualising food frauds diverts attention from systemic, embedded, and cultural regularities associated with business, market, regulatory and political-economic structures. For instance, as above, reducing explanations for food frauds to that of individual ‘rogue’ criminals and/or organised crime groups pathologises food frauds as distinct criminal activities that bear little or no relation to otherwise routine and legal organisational processes. Food frauds are regularly depicted as perpetrated by external crime groups who operate transnationally and threaten the integrity of otherwise robust food systems [14]. This depiction is reflected both at a media and policy level, where headlines such as ‘Crime gangs expand into food fraud’ [29] dominate, and where enforcement agendas have targeted efforts against food fraud at the economic goal-based activities of organised crime groups [30]. This narrative may be convenient for governments as they reduce demands for structural and cultural reforms to dysfunctionality in the food system. Yet enforcement bodies such as the UK NFCU continue to assert that whilst there are exceptions, there does not appear to be any consistent organised crime activity in food fraud, with food crimes commited by those with existing roles in the food system [31: 22], [32: 6]. Simultaneously, however, the NFCU’s response strategy has now fallen in line with the UK Home Office’s Serious and Organised Crime Strategy [33: 1], and this has implications for the framing and response to food frauds in line with strategies developed in response to organised crime.

Analytically, more can be gained by integrating research questions about interactions of individual agency and offender collaborations with the emergence and visualisation of opportunity structures generated by the structures of the food system, including business processes, regulation, markets, and their political-economic governance. Multi-dimensional accounts are key to understanding the social complexity of food frauds and this involves embracing the tensions that exist across varied disciplines. For instance, long (and transnational) supply chains, supply chains with multiple intersections, large multi-national companies with opaque ownership structures, low cost food production and food processing of cheap food residues all contribute to food fraud opportunities. Pressures within particular industries, such as narrow profit margins, the nature of business relationships between farmers and buyers, as well as how easy it is to tamper with specific products, all contribute to a richer understanding of how and why food frauds occur within otherwise legal business settings. Relatedly, food fraud also has political consequences. Governments must constantly ensure that they can deliver food cheaply—there is an interplay between cheap food, food production and government approaches to food regulation that have emerged and are influenced by particular geo-historicl contexts. In the UK, in the post-Brexit period of rapid social change, we can anticipate a changes in regulation as food is sourced outside of EU regulatory framewors, creating spaces for fraudulent actions.

In these terms, germane to producing plausible and practically adequate knowledge is the foregrounding of the interplay between the emergence and visualisation of criminal opportunities, the networks of criminal actors and their respective skills, expertise and abilities, the control mechanisms in place and the varied settings, situations and structural antecedents that shape the concentration or distribution of these varying causal factors. A multi-faceted analysis of how food frauds emerge in particular places and times, and of the diverse antecedents that shape this, offers a more concrete insight into why certain actors become involved in certain types of fraud under different conditions. Analyses of the structure of the market, and in particular clearly integrating analyses of how food is sourced, produced, distributed and marketed relate to criminal opportunities is needed, otherwise the above fault lines will remain in place.

Moving attention from sensational and individualised explanations in order to better understand routine, structural processes, are well-grounded topics in the literature on organisational and corporate crime. In this context, researchers foreground arguments that crimes and harms are routine and systematic by examining ongoing, enduring, complex relationships between private and public actors [34: 177]. In particular, Bernat and Whyte [35] argue that criminal and harmful actions should be analysed as part of broader processes and systems of production, rather than specific ‘moments of rupture’ that serve to separate events from processes. A critical perspective may frame these system-wide analyses as a product of industry structure and vested business ownership and interests, but focusing on the food system at industry and organisational levels provides a more nuanced discussion when compared to explanations based solely on criminality or organised crime.

Fault lines in detecting and preventing food frauds

A second set of fault lines relates to how we detect and prevent food frauds, and in particular the reification of authenticity testing as the policy solution. For instance, in 2020 the UK’s Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology (POST) published a report on food fraud to inform ministers of the state-of-the-art evidence on the issue, and based on a review of the literature and interviews with stakeholders from practice and academia, including natural and social scientists. In terms of detection and prevention, the report concluded that ‘[s]trategies to detect and prevent food fraud broadly fall into two categories: analysis to test the authenticity of foods to verify compliance with labelling and compositional standards, and broader mitigation strategies, such as intelligence gathering’ [8: 3]. The ‘broader mitigation strategies’ were essentially defined in terms of sharing anonymised information and authenticity test results. Such techniques can be targeted or non-targeted, looking for specific DNA or adulterants, or obtaining biochemical footprints to compare expected characteristics respectively. Such testing uses innovative technologies or specialist laboratories. Whilst in the UK detection and prevention, and intelligence sharing, is also a priority of the National Food Crime Unit, despite being established in 2014, the Unit is yet to receive sufficient statutory enforcement powers to investigate food crimes [36]. The key issue is that this high-level POST review of the scientific literature foregrounded varying forms of authenticity testing as the primary solution to detecting and preventing food frauds. This is a dominant narrative in the food fraud academic discourse but whilst it seems appealing and actionable (particularly as such testing at the cutting edge is highly advanced), alone it is superficial and fundamentally flawed under a layer of surface plausibility.

Targets for testing are often very specific foodstuffs and products. These studies often reflect anecdotal concerns from industry actors and/or regulators or reflect strategically haphazard or piecemeal attempts to identify the next food fraud scandal with no particular evidence base for targeting and testing particular products. [Foodstuffs may be chosen on the basis of perceived value, but some ‘cheaper’ products may be more frequently targeted (see [37, 38])]. This latter approach is common in the natural sciences, as food fraud studies move from one foodstuff to the next and utilise analytical techniques to test foods that may in some way be fraudulent. Business and industry have also foregrounded analyticial testing as food standards required more stringent authentication whilst varied organisations have also emerged seeking to offer (and commercialise) analytical testing solutions (for an overview see [39]). This of course has implications for the kinds of data shared by business with the NFCU. A key issue here is that by focusing on the product, fraudulent behaviours are decontextualised and dehumanised, as products, and not the people who conspire to defraud them, become the focus of inquiry. Whilst such approaches can inform an understanding of which foodstuffs have been defrauded, they offer little robust insight into the actual underlying nature, organisation, drivers, conditions or motivations for the frauds and essentially lead to framing food frauds in relation to the intrinsic political decisions of researchers and their methods.

Dehumanising fraudulent behaviours

First, there is an issue of dehumanisation. The desire to frame testing as the solution is understandable from a policy perspective as it constructs an image of a ‘scientific’ approach to fraud detection and reduction. The key issue, however, is the absence of social science to understand the underlying human motivations and behaviours—foods do not adulterate themselves, so focusing on the product and not the people can only be part of the solution. Depriving food fraud responses of the necessary human–social qualities, features and conditions, is pessimistic, failing to foreground behaviour change. Furthermore, as Gussow [9] identifies, routine compliance detection mechanisms rarely detect food frauds alone, particularly as offenders can straightforwardly conceal their activities and circumvent inspection mechanisms. This is significant for those advocating routine (and random) analytical testing as a solution as such procedures are easy to deceive. Instead, much can be learned from the social scientific literature on fraud where we see plausible short-term, medium-term and long-term prevention and reduction strategies that incorporate admixtures of situational (e.g., improving capable guardianship in particular settings where motivated offenders interact with opportunities) and social prevention (e.g., pursuing systemic change to create fairer and more transparent food networks). Situational prevention, for instance, implies the coming together of necessary mechanisms that enable the commissioning of food frauds, that is, understanding how food fraud occurs in different settings, understanding the modus operandi, understanding who is involved and when and why, understanding which actors have key roles in the network and so on., and then building in interventions that can i. increase the effort needed to carry out the fraud, ii. increase the risks associated with the fraud, iii. reduce the potential rewards from the fraud, iv. reduce provocations for the fraud, and v. remove excuses for carrying out the fraud. Lord et al. [26: 484], for instance, present ‘a conceptual and analytical framework for understanding food frauds as situated actions, shaped by contingent enterprise conditions, and developing associated situational mechanisms to prevent and reduce these undesired, “entrepreneurial” behaviours at the level of necessity’. Similarly, van Ruth et al. [25] argue for the systematic evaluation of vulnerabilities within the food system, consisting of developing an evidence base on the opportunities, motivations and control measures to inform intervention and reduction strategies. Thus, as Spink and Moyer [40: R159] note, it is important to recognise that ‘the root cause of food fraud has fundamentally different properties’ to other policy agendas such as food safety.

Decontextualising fraudulent behaviours

Second, there is an issue of decontextualisation. Whilst analytical testing techniques claim to be able to detect fraud, such as adulteration, in reality such testing can at best detect that a fraud has taken place at some point previously in the food supply chain or system. In essence, such testing is an ‘after the fact’ response (identifying that certain foodstuffs were at some point defrauded), rather than a ‘before the fact’ response, seeking to prevent or reduce the number of frauds taking place. Analytical testing removes the context of the actual fraudulent activities and enterprise, providing little insight into how such frauds would in fact be prevented. Whilst one counter-argument may be that analytical testing is in itself a deterrent, and therefore preventative, there is no empirical evidence base for this. Furthermore, this assumes that it is possible to trace back from the point that fraud has been identified to the point where the fraud occurred, but complex food supply networks and associated food industry practices involving production, processing and distribution mean any evidential connections between the perpetrators and the fraudulent foodstuff are difficult to establish. For instance, a producer of burgers or lasagnes may source minced meat from multiple suppliers, domestically and internationally, mixing these ingredients to produce the final product. There may also be multiple layers of brokerage that take place along these supply chains, with ownership varying across and within jurisdictions. Thus, identifying that a burger in a UK supermarket had been adulterated will unlikely deter those engaging in fraud, particularly when there is a transnational component. Similarly, for such testing to act as a general deterrent, it would need to take place at an unmanageably grand scale. For instance, in 2018 in the UK alone there were almost 90,000 restaurant and mobile food businesses (not to mention the hundreds of thousands of other food business types)—analytical testing across all such locations is simply not viable or cost beneficial.Footnote 5

The scope of applicability

Third, there is an issue with the scope of applicability. Whilst analytical testing can, as above, target particular DNA sequences or search for particular characteristics, this is only relevant for a small part of the food fraud ‘problem’. Bouzembrak and Marvin [42], drawing on data from the EU’s Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) established six different food fraud types: (i) improper, fraudulent, missing or absent health certificates, (ii) illegal importation, (iii) tampering, (iv) improper, expired, fraudulent or missing common entry documents or import declarations, (v) expiration date and (vi) mislabelling. Similarly, Manning [43] highlighted varying areas where integrity, and potential frauds, might take place, such as in relation to not only food products (i.e. quality/authenticity) but also food processes (i.e. activities inherent in production), people (i.e. honesty/morality of actors) and data (i.e. consistency and accuracy of accompanying information). With these typologies in mind, analytical testing can inform questions about authenticity and quality, but struggles to identify where a product has been mislabelled (e.g., organic or not? Halal or not?), illegally imported, is missing required documentation, and so on. Thus, whilst academia and policy recognise a diverse array of behaviours that form food fraud (see also [21], for an overview of the evolution of the food crime/fraud concept), analytical testing can only be used to respond to a small segment of these. However, one implication of this narrow relevance of analytical testing is that such approaches nonetheless shape narratives around which foodstuffs are most susceptible to fraud (and consequently more frequently tested) making food fraud realities an artefact of testing regimes.

For knowledge on food fraud detection and prevention to be plausible and have real use for practitioners, it needs to reflect the reality of the dynamics of food fraud and not narrowly delineate or define such situated actions in terms of the constitution of foodstuffs. Analytical testing is not a panacea to food fraud but can undoubtedly be part of a more holistic and integrated human-social-technical detection, prevention and reduction strategy that incorporates public (e.g. enforcement authorities), private (e.g. robust business compliance systems and risk/vulnerability assessments) and civil society (e.g. increased education) actors in order to increase the integrity and resilience of the food system (see also [9]). However, the analytical testing community, as we see in the UK POST report, is setting the research and policy agenda, based on assumptions about patterns and trends of food fraud, and depictions and portrayals, that reflect inferences based on problematic data and political agendas. This in turn confirms the centrality of the natural sciences in the understanding of a social phenomenon to the detriment of the social sciences. A consequence of this is that industry and public research funds are directed towards the testing industry that in turn serves to reinforce the testing approach. Moreover, shifting the agenda towards testing as the solution enables key industry players to claim a valid self-regulatory response whist deflecting the spotlight away from those structures, practices and cultures within the food system that generate increased inequalities and incentivse ‘creative’ business responses to external pressures and accompanying rationalisations for this.

Fault lines in regulating and criminalising food frauds

The third set of fault lines relates to the criminalisation of food frauds given the enforcement tensions between crime control and a food law/regulation underpinned by safety concerns. Recent discussions for the standardisation of the definition of food fraud at the international (CX/FICS 18/24/7 [44]) and European (CEN/WS/086 in European Commission website [45]) levels have defined food frauds as ‘intentionally causing a mismatch between food product claims and food product characteristics’, and as ‘any deliberate action of businesses or individuals to deceive others in regards to the integrity of food to gain undue advantage’, respectively. In the EU there is no legal definition for food fraud. However, the European Commission establishes that food fraud refers to ‘any suspected intentional action by businesses or individuals for the purpose of deceiving purchasers and gaining undue advantage therefrom, in violation of the rules referred to in Article 1(2) of Regulation (EU) 2017/625 (the agri-food chain legislation)’Footnote 6. The agri-food chain legislation, which entered into force in December 2019, broadens the scope of official controls on compliance with EU rules concerning not only the safety of foodstuffs and the integrity of food supply chains, but also includes animal and plant health, animal welfare and environmental issues. The European Commission has further established that the distinction between food fraud and non-compliance is based on four operative criteria, i.e., violation of EU rules (specified in Article 1(2) of Regulation (EU) 2017/625), deception of consumers, intention and economic gain. These criteria limit the applicability of food frauds to those affecting consumers, but is silent about other potential victims such as business partners, in addition to reducing food frauds to those economically motivated and thus, is blind to an array of motivations that may be conducive to food frauds [14]. Despite its focus on regulatory compliance, the agri-food chain legislation [under Article 9] requires competent authorities to provide information about those instances in which ‘consumers might be misled…to the nature, identity, properties, composition, quantity, durability, country of origin or place of provenance, method of manufacture or production of food; and, further identify the possible intentional violation of the rules’. In the absence of a statutory definition of food fraud, the agri-food chain legislation attempts, through this provision, to squeeze acts that could be conducive to frauds (and crimes) within a regulatory framework aimed at identifying non-compliance. However, the enforcement tension between crime control and regulatory breaches extrapolate not only from the lack (or inadequacy) of a statutory definition for food fraud, but also from complexities arising from the fragmentation of competent enforcement authorities and legislation involved in food fraud investigations, as well as from the absence of necessary resources and expertise to investigate and successfully prosecute food frauds [15].

The UK, as the EU, lacks a statutory definition for food fraud. However, the NFCU has differentiated between food fraud and food crime, the latter defined as ‘as a serious fraud and related criminality in food supply chains’.Footnote 7 Despite this distinction, the regulatory framework to address food-related offences relies mainly on the General Food Law Regulation (EC) 178/2002 [46]Footnote 8 and the Food Safety Act 1990 [47], both of which developed as a response to safety concerns. For instance, in her analysis of the UK policy discourse on food crime, Rizzutti [21: 118], notes that ‘UK food policies have focused mainly on ensuring that food is safe and free from intentional and unintentional contaminations, without taking into consideration the possible illicit profiles of the practices that happen inside the food sector beyond food fraud activities’. Although the Food Law Code of Practice (England) 2017 establishes that food crimes should be prosecuted under the Fraud Act 2006 or as conspiracy to defraud under the common law, not all food frauds would be considered serious enough to pursue a fraud prosecution as opposed to strict liability offences under food law and regulations. Thus, food fraud prosecutions have to undergo a subjective test for seriousness based on the detriment to the public, business operators or the UK food industry, the geographical scope of the alleged fraud and the public or political sensitivities towards the case (Food Law Code of Practice (England) 2017 [48]). Including public and political sensitivities in the threshold of seriousness to prosecute a food fraud as a crime seems to respond to an understanding of food fraud as sensational and episodic (see above), and not as a result of routinised activities, culture within industries and the potential misuse and abuse of legal business structures for the organisation of frauds. In addition to this threshold, the NFCU, whose capacity was increased in 2018 to include both intelligence and investigative powers (FSA 18-06-09 [49]), focuses only on seven types of food crimes: theft, illegal processing, waste diversion, adulteration, substitution, misrepresentation and document fraud, limiting therefore the scope of food frauds to certain acts. The NFCU’s threshold, which determines the cases that fall within its new remit, is restricted to serious fraud and related criminality to prosecute under the Fraud Act 2006 or as conspiracy to defraud under common law, only leading on a ‘small number of the most serious and complex investigations’ which comprise strategic priorities (and control strategies), taking into account the geographical scope and scale of the alleged offence, and the extent and nature of the actual, potential or intended (physical or economic) harm (FSA 20-01-18 [50]). The NFCU will be able to support and/or coordinate investigations led by other partners,but, despite these new powers, the NFCU will continue to rely on other authorities, and on securing agreement with relevant partners, and the necessary changes to legislation to access powers under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act, in order to ensure enforceability of food frauds both within and below their remit threshold. As the National Audit Office [36: 9] concludes, the NFCU ‘currently lacks the full range of investigative powers it needs to operate independently’, such as powers of search and seizure. The NFCU futher notes that the reduction of funding, and of food officers in some areas, will affect the collection of intelligence at the local level, thus affecting the UK intelligence concerning non-compliance and food crime [32]. Limited resources and the complexity of the issues involved constraints the potential to conduct long and complex investigations and entails considerations about the best use of public funds [32]. Thus, whilst the Food Law Code of Practice (England) 2017 provides some guidance in terms of food fraud and food crime, the concept remains elusive within a regulatory framework that is geared towards strict liability offences and subjected to a set of criteria that limits the categorisation of deviant conducts as food crimes [15].

Assumptions about the actors are reflected on regulatory approaches such as the FSA’s new ‘Regulating our Future [51]’, which aims to segment business operators according to ‘risk scores’ in order to determine the nature, frequency and intensity of official controls, and where the role of the Primary Authority System is being considered to form part of this regulatory approach (FSA website). The Primary Authority is a scheme under which the food business operators enter into partnerships with local authorities, who in turn help businesses comply with regulation. The operation of the system will determine the national inspection strategies in which the Primary Authority can establish lower and more tailored regulatory interventions for food business operators based on evidence. Whilst this approach seems more targeted, big corporate food groups and business operators with resources would be more likely to enter into partnerships with the local authority and thus, have a more targeted regulatory approach. Reports have shown that big group organisations with a considerable market share can incur in regulatory breaches that are not detected or acted on even when subjected to regulatory and private audits (The Guardian, 2 March 2018 [52]), raising concerns about the inadequacy of some private quality schemes and regulatory audit systems (based on the categorisation of businesses for inspection) to detect non-compliance (UK Parliament [53], 2017 [54]). The FSA’s regulatory approach is based on cooperation and information sharing to establish targeted responses; however, this approach assumes that businesses are willing to cooperate and act responsibly. Furthermore, enforcement authorities would need to have the necessary resources both in terms of finance and expertise to identify and investigate food fraud and food crimes within a fragmented regulatory framework foregrounding safety, guided by conceptualisations that are restrictive about the potential actors and acts, and where only a limited number of food frauds are considered serious enough to be prosecuted as a crime, and investigations led by the NFCU. The tensions between the regulatory framework and the criminalisation of food frauds epitomise the prevalent understanding that food frauds are external to the food system and episodic, characterised as specific acts, restricting the plausibility of food fraud comprising an array of motivations beyond this confined types of food fraud. In order for a regulatory framework to adequately prevent, detect and control food fraud, there is a need to better understand the motivations (from slippery rope, to attempts to keep a business afloat, to normalisation of behaviours in certain industries), and opportunities (deriving from financial, business, market, regulatory, political, economic and cultural structures) behind the commission of food frauds.

Finally, the framing of the food fraud ‘problem’ as discussed above has driven the creation of investigative bodies or departments such as the NFCU in the UK (we see this also in many countries including Ireland, the Netherlands, Italy, Denmark) that are structured as criminal investigative units and often staffed with (ex-)law enforcement actors with varying enforcement powers, depending on jurisdiction. Ostensibly, this seems a plausible policy response given the foregrounding of food crime in domestic (e.g. [27]) and EU discourse (e.g. CoEU, [30]) that in turn gives due attention and recognition to the phenomenon. However, the structure and staffing of such investigative units (i.e. the law enforcement model) predisposes them to pursuing criminal offending as exceptional acts by individual actors, as doing so reflects ‘cop culture’ and catching of ‘bad guys’, and justifying investment and funding through the completion of notable cases (e.g. major seizures of counterfeit alcohols). Doing so is of course important but the key issue is that, as above, this directs attention away from structural and cultural reform of the food system more generally to identify, for example, alternative models of ownership (as we see with cooperative groups rather than corporatised and commodified suppy networks) that can offer better protections to food system actors, reducing opportunities and incentives for fraud that are generated by industry practices and structures.

Conclusion: plausibility and practical adequacy

This article argues that there are fault lines emerging within the scientific and policy literature on the nature, extent and control of food frauds, and in some cases specious constructions of the phenomenon driving research and policy agendas. With focus mainly on the UK context, and certainly not an exhaustive selection of issues, we analysed three sets of fault lines. First, we examined orientations in food fraud research in relation to the foregrounding of food fraud acts and actors. There is an over-reliance on enforcement data in the development of food fraud concepts and realities, with corresponding research methods producing what constitutes the ‘thing’ itself and with a neglect of the need for reflexivity of our methodological preferences. Relatedly, we critiqued depictions of the extent of food frauds as episodic and exceptional, and as a product of exogenous threats to the food system. The concern with such depictions is that they obscure the diverse array of food frauds that are embedded within the food system, but which are perceived as more mundane and routine. Alongside this, literature that individualises the occurrence of food fraud neglects and diverts attention away from a deeper empirical investigation of the systemic, embedded, and cultural regularities associated with business, market, regulatory and political-economic structures that drive fraudulent behaviours. Second, we questioned the relevance of analytical testing as the solution to food fraud detection, prevention and reduction. In our view, foregrounding such testing dehumanises and decontextualises the multi-faceted antecedents and complexities of food frauds as situated actions. Whilst analytical testing has some use as part of a broader control response, its scope of applicability is narrow. Third, we highlighted issues relating to the criminalisation of food frauds and in particular the tensions that exist between crime control and regulation, and the different legal responses that these models imply.

To conclude, our key purpose is to argue that the fault lines identified in this article raise significant questions over how plausible different accounts (and associated knowledge production) of food frauds actually are, and draw attention to the relationship between science and policy, and the tensions that exist. In our view, this is significant for food fraud policy, strategy and operation, and for how we generate expectations about the actual realities of food fraud and corresponding actions that are realised, and make knowledge practically adequate. We encourage the pursuit of new and alternative empirical data in this field, that is reflexive and critical of the approach to producing knowledge on food fraud, and that in turn is able to inform robust conceptualisation and abstraction, and provide insights into the underlying social structures and relations that create mechanisms that enable, or restrict, opportunities for, and actual occurrences of, food frauds as part of social complex food systems. This requires the coming together of varied disciplines, and the embracing of tensions that exist between and within the social and natural sciences, to produce multi-dimensional accounts of the nature, organisation and control of food frauds.

Notes

Search undertaken on the CLSC website on 11 February 2021.

See https://www.ssafe-food.org <last accessed 11 February 2021>.

See also Goodall (this issue) on contentless abstractions in relating to ‘poaching’ and ‘organised crime’.

See https://www.statista.com/statistics/298871/number-of-restaurants-in-the-united-kingdom/. See also the FSA, Annual Report on Local Authority Food Law Enforcement for England, Northern Ireland and Wales (1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019 [41]). According to this report, 62% of Trading Standards Local Authorities had around 10% of establishements awaiting for an initial inspection and 21% of Trading Standards Local Authorities had more the 20% of establishments not yet rated.

https://ec.europa.eu/food/safety/agri-food-fraud/food-fraud-what-does-it-mean_en <Accessed 3 August 2021>

The EU General Food Law is applicable in the UK after the EU-exit until the end of the transitional period on 31 December 2020. General Food Law will be retained as amended under the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018.

https://www.food.gov.uk/safety-hygiene/food-crime (accessed 15 February 2021).

References

Manning, L., & Soon, J. M. (2016). Food safety, food fraud, and food defense: A fast evolving literature. Journal of Food Science, 81(4), R823–R834.

Sayer, A. (2010). Method in social science: A realist approach. Routledge.

Matthews, R. (2009). Beyond ‘so what?’ criminology: Rediscovering realism. Theoretical Criminology, 13(3), 341–362.

Bhaskar, R. (2008). A realist theory of science. Verso.

Matthews, R. (2014). Realist criminology. Palgrave Macmillan.

Edwards, A. (2017). Multi-centred governance in liberal modes of security: A realist approach. PhD thesis, Cardiff University.

Cohen, S. (1998). Against criminology. Routledge.

UK Parliament. (2020). Food Fraud POSTNOTE Number 624. Retrieved from https://post.parliament.uk/research-briefings/post-pn-0624/. Accessed 3 Aug 2021.

Gussow, K. E. (2020) Finding food fraud: Explaining the detection of food fraud in the Netherlands, PhD thesis, VU Amsterdam. Retrieved from https://research.vu.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/98535011/Finding_Food_Fraud_Gussow_2020Apr24.pdf. Accessed 3 Aug 2021.

van Ruth, S. M., Luning, P. A., Silvis, I. C. J., Yang, Y., & Huisman, W. (2018). Differences in fraud vulnerability in various food supply chains and their tiers. Food Control, 84, 375–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.08.020.

Yang, Y., Huisman, W., Hettinga, K. A., Liu, N., Heck, J., Schrijver, G. H., Gaiardoni, L., & van Ruth, S. M. (2019). Fraud vulnerability in the Dutch milk supply chain: Assessments of farmers, processors and retailers. Food Control, 95, 308–317.

Yang, Y., Huisman, W., Hettinga, K. A., Zhang, L., & van Ruth, S. M. (2020). The Chinese milk supply chain: A fraud perspective. Food Control, 113, 107211.

Kendall, H., Kuznesof, S., Dean, M., Chan, M.-Y., Clark, B., Home, R., Stolz, H., Zhong, Q., Liu, C., Brereton, P., & Frewer, L. (2019). Chinese consumer’s attitudes, perceptions and behavioural responses towards food fraud. Food Control, 95, 339–351.

Lord, N., Flores Elizondo, C., & Spencer, J. (2017). The dynamics of food fraud: The interactions between criminal opportunity and market (dys)functionality in legitimate business. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 17(5), 605–623.

Flores Elizondo, C. J., Lord, N., & Spencer, J. (2018). Food Fraud and the Fraud Act 2006: Complementarity and limitations. In C. Monaghan & N. Monaghan (Eds.), Financial crime and corporate misconduct: A critical evaluation of fraud legislation (pp. 48–62). Routledge.

Gray, A. (2018). A food crime perspective. In A. Gray & R. Hinsch (Eds.), A handbook of food crime (pp. 11–26). Policy Press.

Passas, N. (2005). Lawful but awful: ‘Legal corporate crimes.’ Journal of Socio-Economics, 34(6), 771–786.

Tombs, S., & Whyte, D. (2015). The corporate criminal: Why corporations must be abolished. Routledge.

Davies, J. (2018). From severe to routine labour exploitation: The case of migrant workers in the UK food industry. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 19(3), 294–310.

Leon, K. S., & Ken, I. (2019). Legitimized fraud and the state–corporate criminology of food—A Spectrum-based theory. Crime, Law and Social Change, 71, 25–46.

Rizzutti, A. (2020). Food crime: A review of the UK institutional perception of illicit practices in the food Sector. Social Sciences, 9(7), 112.

Grylls, B. (2020). Shocking number of avocado oils sold in US are rancid or adulterated. In New food magazine, 18 June. Retrieved August 26, 2020, from https://www.newfoodmagazine.com/news/112231/food-aduleration/

Mehmet, S. (2019). New Zealand directs milk suppliers to stop selling unpasteurized milk. In New food magazine, 06 December. Retrieved August 26, 2020, from https://www.newfoodmagazine.com/news/100284/new-zealand-directs-milk-suppliers-to-stop-selling-unpasteurised-milk/

Mehmet, S. (2020). Punjab Food Authority stops production of fraudulent ketchup factory. In New food magazine, 23 January. Retrieved August 26, 2020, from https://www.newfoodmagazine.com/news/103845/punjab-food-authority-stops-production-of-fraudulent-ketchup-factory/

van Ruth, S., Huisman, W., & Luning, P. A. (2017). Food fraud vulnerability and its key factors. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 67, 70–75.

Lord, N., Spencer, J., Albanese, J., & Flores Elizondo, C. (2017). In pursuit of food system integrity: The situational prevention of food fraud enterprise. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 23(4), 483–501.

Elliot, C./HM Government. (2014). Elliott review into the integrity and assurance of food supply networks—Final report: A national food crime prevention framework, Crown Copyright.

Leon, K. S., & Ken, I. (2017). Food fraud and the partnership for a “Healthier” America: A case study in state–corporate crime. Critical Criminology, 25, 393–410.

Guardian. (2014). Crime gangs expand into food fraud, 03 May. Retrieved August 26, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/may/03/crime-gangs-target-food-fraud-draft-eu-report

Council of the European Union. (2014). Draft Council Conclusions on the role of law enforcement cooperation in combating food crime. 15623/14.

NFCU. (2016). Food Crime Annual Strategic Assessment. Food Standards Agency/Food Standards Scotland. Retrieved from https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/fsa-food-crime-assessment-2016.pdf. Accessed 3 Aug 2021.

NFCU. (2020a). Food Crime Strategic Assessment 2020, Food Standards Agency/Food Standards Scotland. Retrieved from https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/food-crime-strategic-assessment-2020_2.pdf. Accessed 3 Aug 2021.

NFCU. (2020b). National Food Crime Unit Control Strategy 2020–21, Food Standards Agency. Retrieved from https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/nfcu-control-strategy-2020-21_0.pdf. Accessed 3 Aug 2021.

Tombs, S. (2012). State-corporate symbiosis in the production of crime and harm. State Crime Journal, 1(2), 170–195.

Bernat, I., & Whyte, D. (2017). State-corporate crime and the process of capital accumulation: Mapping a global regime of permission from Galicia to Morecambe Bay. Critical Criminology, 25, 71–86.

National Audit Office. (2019). Ensuring Food Safety and Standards, HC 2217, NAO.

Lord, N., Spencer, J., Bellotti, E., & Benson, K. (2017). A script analysis of the distribution of counterfeit alcohol across two European jurisdictions. Trends in Organised Crime, 20(3–4), 252–272.

Spencer, J., Lord, N. and Flores Elizondo, C. J. (2020). Distribution and consumption of counterfeit alcohol: Getting to grips with fake booze, Alcohol Change UK, available at: https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/files.alcoholchange.org.uk/documents/The-distribution-and-consumption-of-counterfeit-alcohol-Final-Report.pdf?mtime=20200729081548

IFST. (2019). Food authenticity testing part 1: The role of analysis. Institute of Food Science and Technology. Retrieved from https://www.ifst.org/resources/information-statements/food-authenticity-testing-part-1-role-analysis

Spink, J., & Moyer, D. C. (2011). Defining the public health threat of food fraud. Journal of Food Science, 76(9), R157–R163.

FSA (2019) Annual Report on Local Authority Food Law Enforcement for England, Northern Ireland and Wales (1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019), Food Standards Agency, available at: https://www.food.gov.uk/newsalerts/news/fsa-publishes-latest-annual-report-on-local-authority-food-law-enforcement

Bouzembrak, Y., & Marvin, H. J. P. (2016). Prediction of food fraud type using data from Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) and Bayesian network modelling. Food Control, 61, 180–187.

Manning, L. (2016). Food fraud: Policy and food chain. Current Opinion in Food Science, 10, 16–21.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization (2018) Joint FAO/WHO Food Standards Programme, Codex Committee on Food Import and Export Inspection and Certification Systems, Twenty Fourth Session, CX/FICS 18/24/7 (August 2018), available at: http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/en/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FMeetings%252FCX-733-24%252FWorking%2BDocuments%252Ffc24_07e.pdf

European Commission. (no date). Food Fraud. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/knowledge4policy/food-fraud-quality/topic/food-fraud_en. Accessed 3 Aug 2021.

General Food Law Regulation (EC) 178/2002.

Food Safety Act. (1990).

Food Law Code of Practice (England). (2017). Available at: https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/food-law-code-of-practice-england.pdf

Food Standards Agency. (2018). The Development of the National Food Crime Unit and the Decision to Proceed to Phase 2, FSA 18-06-09, available at https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/NFCU%20Business%20Case%20Report%20-%20FSA%2018-06-09.pdf. Accessed 3 Aug 2021.

Food Standards Agency. (2020). National Food Crime Unit – Update on Progress, FSA 20-01-18, available at: https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/national-food-crime-unit-update-on-progress-january-2020.pdf

Food Standards Agency. (2018). Regulating our Future, Changing Food Regulation: what we’ve done and where we go next, Food Standards Agency, available at: https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/changing-food-regulation-what-weve-done-where-wego-next_0.pdf

Monaghan, A. (2018). ‘2 Sisters guilty of poor hygiene poultry plants, FSA finds’, The Guardian, 2 March 2018, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2018/mar/02/2-sisters-guilty-of-poor-hygiene-at-poultry-plantsfsa-finds

UK Parliament. (2017). 2 Sisters and Standards in Poultry Processing, Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee, First Report of Session 2017-2019, HC490 (15 November 2017), available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmenvfru/490/49003.htm

European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. (2017). Regulation (EU) 2017/625) of the European Parliament and of the Council, Official Journal of the European Union, L95/1, available at: https://eurlex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32017R0625&from=EN. Accessed 3 Aug 2021.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the writing of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lord, N., Flores Elizondo, C., Davies, J. et al. Fault lines of food fraud: key issues in research and policy. Crime Law Soc Change 78, 577–598 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-021-09983-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-021-09983-w