Abstract

This paper explores antifa activists’ use of doxing on Twitter against individuals perceived as alt-right militants. Following the principles of Grounded Theory, we collected 4690 tweets published by antifa users between September 2019 and September 2020 and analysed a random subsample of 1638. Results show that antifa users perceive alt-right activists as a serious threat to their worldview and seek to neutralise their activism even at the cost of making them social pariahs. To achieve that goal, antifa activists collect personal data on persons they suspect of being alt-right activists to “build a case” and then disseminate that information through different virtual social networks to the largest audience possible. The aim of doxing is to encourage other social actors to react and take actions that could be detrimental to the individual targeted. The article discusses practical and ethical implications of this kind of political-based harassment and suggests that future research on doxing could focus on antifa blogs and websites, which include sensitive information forbidden on Twitter.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

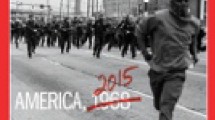

The election of Barack Obama, the first African American President of the United States (US), in 2008 marked the genesis of a prominent social movement on the American political right (Bray, 2017; Burley, 2017; Vysotsky, 2020). Richard Spencer, a leading figure of that movement, defines it as the Alt-Right, an abbreviation of alternative right (Southern Poverty Law Center, (SPLC), n.d.-a). Based on the definition proposed by the SPLC—a non-profit legal advocacy organisation that defines itself as “working in partnership with communities to dismantle white supremacy, strengthen intersectional movements, and advance the human rights” (SPLC, n.d.-d)—the alt-right is a social movement composed by groups and individuals with far-right ideologies whose common denominator is the belief that the white civilisation is under siege by left-wing forces advocating political correctness and social justice to promote a multicultural society (SPLC, n.d.-d). This alternative right, often synonymous with far-right, white supremacism, or (neo)fascism, has been instrumental in the resurgence of the antifa (short for antifascism) movement (Bray, 2017; Vysotsky, 2020), which originated during the interwar period as a response to Mussolini’s fascism in Italy in 1922. Antifa is considered as cyclical because it comes back periodically as a counterbalance to new forms of fascism. Hence, after a first wave of antifascist movements in the 1920s and a second one that started in the 1970s, the rise of the alt-right in 2016 led to the rise of a third antifascist movement in the US (Bray, 2017; Vysotsky, 2020).

Drawing from the actions and iconography of previous antifascist waves, 21st-century antifa advocates for direct, occasionally violent, action against their primary political adversaries. The movement also views the state and liberal democracies as incapable of effectively combating fascist ideologies (Bray, 2017), a belief stemming from its anarchist origins and compounded by the fact that the criminal justice system is bound to prosecute antifa activists for illegal activities (Bray, 2017; Vysotsky, 2020). Consequently, antifa activists consider the state as complicit in fostering fascism and depict their struggle as a three-way fight in which they face not only fascism but also the state (Bray, 2017; Vysotsky, 2020). Third wave antifascist groups comprise members based in the same town or region and adopt a decentralised and non-hierarchical structure for decision-making based on unanimity or a strong qualified majority (Bray, 2017; Vysotsky, 2020). The tenure of President Donald Trump, which began in 2017, witnessed an escalation in physical confrontations between the alt-right and antifa activists, occasionally resulting in fatal incidents (Bray, 2017; Vysotsky, 2020).

Notwithstanding, the distinguishing feature of the contemporary antifa movement is its sophisticated usage of information technology, with cyber-violence emerging as a prominent mode of action. In that context, this article analyses on the antifa activists’ use of doxing against individuals labelled as belonging to the alt-right (Bray, 2017; B. Jones, 2020; Vysotsky, 2020). Doxing involves the public disclosure of personal information to intimidate, humiliate or inflict harm to the targets (Douglas, 2016). The term is a contraction of the expression “documents dropping”, derived from the abbreviation of documents as docs or dox often used by hackers.

Despite significant attention given to antifa activists’ doxing practices by media and communication scholars (Klein, 2019; Neumayer & Valtysson, 2013; Nuernbergk, 2015), a glaring gap remains in criminological literature offering a comprehensive analysis of this phenomenon. This article focuses on the antifa activists use of doxing on the social media platform Twitter. The aim is twofold. First, we explore a phenomenon that can be considered as cyber-enabled. Second, through analysing its operational mechanism and the potential repercussions for those targeted, we underscore ethical dilemmas, risks of overreach, but also prospects for crafting evidence-based prevention strategies. These strategies can be pivotal in mitigating and managing deviant behaviours emanating from both the far-right and far-left political spectrums.

Literature Review

Doxing can be conceptualised as a contemporary online form of gossiping. Evolutionary theory posits that gossip has been a fundamental mechanism for fostering cohesion within large social groups, not only through the exchange of information about the dynamics of their social network, but also by serving as a means for controlling deviant behaviours (Dunbar, 2004). Social anthropologists and ethnographers have shed light on the role of gossip within small communities, such as the Andalusian village of Grazalema studied in the mid-twentieth century by Pitt-Rivers (1954), who suggested that in extreme cases, exile remains the only effective refuge from gossip. The advent of virtual social networks has fundamentally transformed the world in a complex global village—surpassing even the vision of McLuhan (1964)—where gossip in the form of doxing can be ubiquitous. Furthermore, the goal of gossip can sometimes be to expel an individual from the group or the community. While not being the main goal of antifa activists, doxing can also result in exclusion when far-right militants do not disengage from their far-right activism (Vysotsky, 2020). In such instances, doxing can transmute into a form of online vigilantism, with all the inherent risks of overreaches that it presents (Bateson, 2021; Smallridge et al., 2016). This section, however, does not focus on gossiping or vigilantism, but reviews the few available studies on doxing.

According to research conducted by Bray (2017) and Vysotsky (2020), most of the actions performed by antifa members are physically nonviolent. Their aim is to build an “anti-fascist culture” and they consist mainly in intelligence gathering, education campaigns, and public humiliation campaigns. Intelligence gathering is conducted using publicly available data on the internet (OSINT: Open-source intelligence), although in rare instances, may involve antifa activists infiltrating far-right groups. Education campaigns launched by antifa groups aim to inform their communities about the ideology, symbols, and activities of the fascist movement. This might involve the production of informational material outlining how to identify a fascist group by its logo, ideology, or recent actions. The information gathered is then used for public shaming campaigns, in which doxing plays a pivotal role as it is used to reveal the political ideas of the targeted individuals to their community, acquaintances, employers, or landlords (Bray, 2017; Vysotsky, 2020). Antifa operates from the premise that belonging to a fascist group is morally reprehensible and incompatible with democratic society. According to Vysotsky (2020), doxing is designed to increase the costs of engagement in fascist movements. Antifascist activists aim to demobilise the fascist movement, aiming that one way to accomplish this is through doxing campaigns that apply social pressure on affiliated individuals.

Analysing how the identities of marginal and disorganised groups are presented through their publications on social networks, Xu (2020) found that some users—both from the alt-right and from the antifa movements—belong to community elites, or are even opinion entrepreneurs, and they frequently quote members of their community in their tweets. They both make use of specific hashtags (hashtags are words or unspaced phrases prefixed with a number [#] sign) in their profile descriptions and send tweets to display their group membership. Alt-right activists often use hashtags associated with the antifa movement to “troll” their opponents, meaning to draw them into futile discussions potentially harmful to them (March & Marrington, 2019). Nevertheless, antifa activists seldom engage in such discussions, opting to use hashtags that incite direct action against the alt-right activists, either in the form of offline political mobilisations (#defendPDX) or cyber-attacks.

Existing research on antifa activists’ use of doxing is sparse, but studies on doxing used by other groups can provide insight. For instance, Snyder et al. (2017) conducted quantitative research on doxing cases from anonymous sharing sites and developed an automatic detection system that filters the raw data and highlights cases of doxing. They then manually coded the information included in a sample of 464 doxing cases randomly selected from the 5530 that had been automatically detected. They found that the average age of the victims was 21, that 80% of them were males, that 64.5% of the addressed mentioned were in the USA, and that, among doxing cases in which motivations were mentioned, only 1.1% were politically motivated. The main information disclosed was home address, telephone number, information about the victim’s family and e-mail address (Snyder et al., 2017).

Eckert & Metzger-Riftkin (2020) interviewed 15 victims of doxing in Western countries who identified themselves as gender or sexual minorities and LGBTQI + activists. The victims perceived doxing as an additional—in this case, online—practice of harassment conducted by politically motivated perpetrators trying to silence or punish them due to their gender identity or activism. The information used by the perpetrators was gathered from open sources and victims found little support from the companies running the social networks or from the police, in such a way that they usually had to deal with the situation on their own.

Chen et al., (2018; 2019) studied victimisation among secondary school students in Hong Kong. Using a representative sample of this population (N = 2,120), they found that between 15 and 30% had been victims of doxing and that girls were overrepresented among the victims. For girls, doxing took place mainly on social networks and instant messaging services, while for boys it usually took place through other means of communication such as e-mails, blogs, and online discussion forums. The perpetrators were known to the victim, mostly other schoolchildren. Among victims, doxing was often associated with psychological problems such as depression, anxiety, and stress.

Finally, Lee (2020) investigated the doxing of police officers by activists during the pro-democracy protests that took place in Hong Kong in the summer of 2019. Data were collected from online discussion forums of the pro-democracy social movement and consisted of 464 comments from two threads focused on the doxing of police officers. Users of the forum, being aware of the illegal potential of this practice, used linguistic strategies to minimise the risks undertaken. Hence, their comments were ironic, euphemistic, or took the form of dehumanising metaphors (e.g., “police dog”). They justified doxing by arguing that it is a form of self-defence or that it is neither illegal nor immoral because the data was obtained from open sources.

The various studies reviewed provide a diverse view of the dynamics, motivations, and impacts of doxing. Given the differences in research methodology, the samples used, and the contexts they address, it is challenging to make direct comparisons between these studies. Each piece of research offers unique insights into doxing as a phenomenon. In the discussion, however, we will try as far as possible to put our findings in the context of those reviewed in this section.

Data and Methods

Data Collection and Analysis

In this research, we utilised the principles of GT to examine the phenomenon of doxing as employed by antifa activists. Grounded Theory (GT) as developed by Glaser and Strauss (1967), and further refined by Corbin and Strauss (2007), is a research method rooted in an inductive and iterative process of generating knowledge. Rather than starting with an established theory and testing it against collected data, GT commences with the data, gradually building a theory out of it. This method is particularly valuable in researching under-explored fields, where pre-existing theories may be scant or non-existent. We recognise, however, that the theories developed in such a way inherently have limitations, particularly when dealing with a limited dataset and in a field that is simultaneously evolving as we observe it. Though researchers often prefer to label their interpretations as theories, it might be more accurate in this context to consider these as interconnected hypotheses. These hypotheses, derived from our current data, will need further testing in the future to substantiate their validity and applicability as the field of study continues to develop.

Data consisted in a sample of 1638 tweets, selected according to a random procedure described below from 4690 tweets that were published during a period of 13 months, from the beginning of September 2019 to the end of September 2020. The starting point was the Twitter profile of a leading antifa user that only subscribes to users affiliated with the antifa movement. We used the script Twitter Intelligence Tool (Twint),Footnote 1 coded in the Python language, to compile a list of 73 accounts to which this activist was subscribed. To ensure that this subscription list included only members of the antifa movement, we conducted a manual verification that consisted in controlling the username, profile pictures and user profile descriptions of the accounts.

The next step was to download all the publications of the antifa users during the period under study and to thorough examine them in order to isolate those related to doxing. The criteria for associating a tweet with a case of doxing were the association of a first and/or last name with an alt-right group, the presence of a telephone number, e-mail address and/or profile on other platforms/social networks of the target of the doxing or its entourage (e.g., family, employer, landlord). In case of doubt, the tweets were consulted directly on Twitter. Furthermore, if a tweet was labelled as being of interest, all the tweets in the discussion thread were also labelled as such, even if prima facie they did not meet the criteria mentioned above. This is because our exploratory research showed that, as the number of characters in a tweet is limited, antifa users post doxing information in several tweets in the same discussion thread. In this way, we compiled a database of 4690 tweets.

The presence of the discussion threads did not allow us to select in a completely random way the final sample for this research (i.e., we could not simply use a table of random numbers to select one third of all tweets) as we could end up with tweets that do not make sense out of the context (i.e., the discussion thread) in which they were created. Consequently, each time the random number pointed to a tweet included in a discussion thread, all the tweets included in that thread were incorporated to the final sample. The latter includes 1638 tweets.

The contents of these tweets were analysed and coded using the software QSR-Nvivo. This is a Computer-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS) often used to support qualitative content analysis (Hutchison et al., 2010). The data analysis was split into three phases:

-

(1) Open coding: This initial phase involves sorting the data into codes that closely resemble the original information. Some of the initial codes may be named in vivo (i.e., a term or concept present in the data is elevated to the status of code).

-

(2) Axial coding: During this phase, the codes identified in the open coding phase are consolidated into categories (Charmaz, 2006) and, at the process advances, some of the later begin standing out as more significant than others in respect to the phenomenon under study (Garson, 2016), which leads to step 3.

-

(3) Selective coding: This final phase involves identifying and focusing on the most salient categories established in the previous phase. These are the categories that best illuminate the phenomenon being researched and form the foundation for the development of a theoretical framework.

The axial coding stage was conducted at regular intervals, particularly when the quantity of open code was large. This approach was deliberate with a view to cultivate an iterative process between open coding and axial coding. Hence, when a category preceded its relevant code, we coded the data and classified the newly created open code directly into that category. Once we open-coded the entire dataset, we continued the categorisation work. Thorough this categorisation procedure—in an effort to improve the construct validity of the categories—we did not refrain from revisiting the original data source (either to the file downloaded or to the original tweet in a web browser) whenever there was a doubt. In a further endeavour to strengthen the study, a method of inter-rater reliability was integrated. This involved the second author performing a critical review of the initial 300 coded tweets. This measure was incorporated to establish a level of consensus and thus bolster the reliability and validity of the coding process.

Ethical Considerations

The political nature of our subject of study makes it difficult to approach it from a completely neutral point of view. We sought to be as objective as possible while being reflexive—that is to say while being aware of one’s relationship to the subject of study and the data (Engward & Davis, 2015)—and with that aim we applied the model of Alvesson & Skoldberg (2009, as seen in Engward & Davis, 2015), which identifies four dimensions that require reflexivity:

-

1.

The problematisation of the empirical material: The data integral to this research was principally derived from antifa users who actively disseminated content on the popular social networking platform, Twitter. Consequently, the data available are those that users chose to share on this platform and that abide by its terms and conditions; or at least those that, at the time of data collection, had not been removed by Twitter yet. This method ensures non-intrusion into the private domain of the tweet authors; moreover, since the tweets have been de-identified, there is no encroachment upon the private sphere of the doxing targets.

The data were collected using the python-coded script Twint instead of Twitter’s API, which means that there was no human influence on the data collection. However, one cannot exclude that the official Twitter’s API could have collected a larger corpus of tweets. We tested that hypothesis at the beginning of the research by comparing the tweets available on the platform and those uploaded by the script without finding observable differences. Inversely, during the data collection, we regularly consulted the tweets identified by Twint—mainly to access their images—without finding inconsistencies. In sum, both during data collection and coding, we never found a tweet that had been omitted by the script, reaffirming its reliability during both the data collection and coding phases.

-

2.

The researcher’s engagement with the interpretative act: Although data were coded and analysed using a Computer-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software, they were first collected and then coded by the first author. This could potentially introduce interpretation bias, impacting the research’s reliability. To mitigate this possible bias, we adhered to the recommendations of Charmaz (2006) and performed the initial coding trying to remain as close as possible to the content of the data.

-

3.

Clarification of the political-ideological context: As the data were collected through an automated script, there was no risk, at that stage of the study, of introducing any political or ideological bias. However, such bias could potentially influence the data analysis phase. For the sake of transparency, the first author wishes to disclose his political leanings align with the libertarian left, akin to the antifa movement, albeit he does not engage in direct activism against alt-right militants to the same degree as certain antifa activists. The second and third authors were his supervisors for this work and accompanied him during the process, challenging his interpretations to assure a relative neutrality.

-

4.

Issues of representation and authority: This research exerts no influence on the contents uploaded by antifa users on Twitter because it was conducted after their publication. This means it can be considered as non-intrusive research.

Data Description

The presence of discussion threads means that the 1638 tweets of our sample correspond to 804 doxing cases, which in turn concern 146 targets—a person can be the object of several cases—of which 135 men and 11 women.

About 65% of the identified targets were featured in between one and three tweets posted. The maximum number of tweets concerning a single target is 35. In addition, 63% of the targets identified with a tweet were targeted by users other than the antifa users included in our sample, which means that the original doxing tweets were retweeted by sympathisers of the antifa movement. In addition, some of the identified targets appear in the tweets of several of the antifa users included in this research.

The doxing tweets came from a pool of predominantly US-based antifa users, with a mere ten tweets originating from users based in the UK. As the tweets originated in these two countries, it is reasonable to assume that users are also based on them. It is true that it would be possible for them to use a virtual private network (VPN) to use an IP from another country, but that would be of little interest for them because one of their goals is to show the community they belong to (Bray, 2017; Vysotsky, 2020).

Table 1 illustrates the eleven most important categories identified when coding the data. As the same data segment can be associated with several categories, these are not mutually exclusive, resulting in the grand total that surpasses the 804 tweets analysed. The Table can be read in a linear way. For example, 666 of the 804 tweets (i.e., 82.8% of them) included general information about the target; conversely, this means that only 17.2% of them did not include that kind of information.

Findings

The categories in Table 1 can be grouped into four main topics identified in the doxing tweets: (1) Target information, (2) Neutralisation techniques, (3) Twitter features, (4) Evidence, and (5) Doxing impact. These are presented in the following sections together with some tweets that illustrate the salient elements of each category. All the tweets below have been de-identified. In the last part of this section, we present the way in which the social reaction is exploited and the consequences of doxing for its victims.

Target Information

The first topic that emerges from the doxing tweets is the information shared by antifa users about their target. Within this topic, we have identified the categories General information, Neutralisation techniques, and alt-right organisations.

General Information about the target

In this work, general information is understood as a type of information that is not specific to alt-right activists. The kind of general information shared by antifa users consists of five subtypes.

-

1.

Target’s full name: The instances wherein only the first name of the target is referenced are scarce, limited to merely five cases. In all other instances, users disclose the complete name, comprising both the first and last names, of their intended targets.

-

2.

Occupational activities: Tweets can include the target’s occupation, academic pursuits, leisure activities, or the organisation that employs them. On occasion, they also provide the employer’s contact details, such as telephone number or e-mail address.

-

3.

Online username: Tweets usually include the pseudonym(s) used by the target across various platforms.

-

4.

Geographical information: Tweets may specify the city or state in which the target resides. However, precise residential addresses were only disclosed in two of the analysed tweets.

-

5.

Age and distinctive physical features: This type of general information is rarely found within the tweets. The few mentions found refer to the tattoos wore by the targets.

Neutralisation Techniques

In general, antifa users justify their use of doxing by emphasising two main arguments that can be conceptualised as neutralisation techniques (Sykes & Matza, 1957): (a) the target’s actions are perceived and presented as reprehensible, and (b) the exposure of the target’s engagement with the alt-right, either digitally or offline. Examples of digital misconduct include sharing derogatory or racist comments about minority groups on social media, joining a right-wing extremist forum, or sharing right-wing extremist propaganda. The main form of offline misbehaviour is participation in right-wing social (e.g., concert) or political (e.g., demonstration) events. Antifa users also expose in their tweets the acts of aggression committed by targets against counter-protesters (e.g., antifa users) or the use of alt-right signs and symbols such as Nazi salutes or swastikas. Less frequently, antifa users mention judicial decisions against the target, as well as other types of crimes committed by the target, such as domestic violence.

Excerpt 1: FIRSTNAME_LASTNAME, from CITY_RESIDENCE, STATE_RESIDENCE, participated for 4 YEARS in the #ironmarch forum where he defined his ideology as fascist; spoke of Jews as satanic rats; wanted to join the neo-Nazi hate group Traditionalist Workers Party; was in the Asatru Folk Assembly.

Excerpt 2: Today, our information indicates that FIRSTNAME1_LASTNAME1, a member of the hate group Proud Boys, assaulted people in the city centre of CITY. FIRSTNAME1_LASTNAME1 is best known for participating in fascist rallies with his Proud Boys roommate, FIRSTNAME2_LASTNAME2, who intentionally boiled his child’s hands.

In relation to the second type of argument—exposing a form of affiliation with the alt-right—antifa users first mention the hierarchical status of the target within alt-right organisations. In most cases, the targets occupy management positions in them. For example, a member of the Proud Boys group was revealed to hold the position of Sergeant at Arms (Feuer, 2021). Another way of exposing the target’s involvement with the alt-right is to uncover their social ties with known alt-right figures. For example, antifa user’s scrutinise the lists of friends of their targets in social media—using any open source accessible through OSINT searches, such as Facebook—and display those who are prominent alt-right activists.

Excerpt 3: Today we expose FIRSTNAME_LASTNAME from CITY_RESIDENCE, STATE_RESIDENCE, who is a white supremacist who openly argues that “All Muslims and Jews should be exterminated”. FIRSTNAME_LASTNAME has just under 100 friends on VKontakte, but one of his friends is Chester Doles, the founder and leader of #AmericanPatriotsUSA from Northern Georgia, USA.

Alt-Right Organisations

The antifa users in our sample mention 34 alt-right organisations. Among these, ten organisations account for 80% of the mentions: Proud Boys, American identity movement, Patriot front, Atomwaffen division, Panzer Street wear, KKK, Blood and honour (UK), Identity Evropa, Boogaloo boys and League of the South. The main target is the Proud Boys movement that accounts for 27% of all mentions. Aside from Panzer Street wear, a neo-Nazi clothing company, and the Boogaloo boys, which aligns more with a political movement (SPLC, 2021), all of the groups listed above are categorised as right-wing hate groups by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC, n.d.-b).

Twitter Features

The two prominent features of Twitter used in the doxing tweets analysed are mentions (including another person’s username prefixed with an at [@] sign, which is a way of sharing a tweet) and hashtags (words or unspaced phrases prefixed with a number [#] sign). Mentions can relate to fellow far-left users, alt-right users or persons related somehow to them. The first category is distinctly more common, as users frequently mention other antifa users, journalists and activists aligned with the antifa movement. Consequently, it is commonplace to find a comment from the doxing user within a doxing conversation, where they quote a series of other antifa users. This practice fosters a flow of information within extreme left-wing circles, especially when the original message begins to circulate via retweets. Antifa users also tend to mention organisations—such as the Southern Poverty Law Center (@splcenter)—that advocate against extreme right groups as well as left-wing social scientists. This may serve multiple purposes, such as alerting them to the situation or soliciting their direct or indirect support.

Contrastingly, antifa activists may also mention users related directly or indirectly to the doxing targets. This can include their employers, customers, schools, universities, or the digital platforms they use (e.g., PayPal or Instagram), but also the local media or the local political authorities of the regions where the targets live.

Despite hashtags being an important feature of Twitter, antifa activists use them rather sparingly. In our analyses, we identified five categories of hashtags. The most important concerns specific doxing campaigns, in the sense that antifa users create a hashtag to group their posts and link several instances of doxing on Twitter. For example, an alt-right discussion forum was hacked in November 2019—the origins of the hacking and the motives remain unknown—and its data were published freely on the internet (Wilson, 2019). Antifa capitalised on this data leak to orchestrate doxing campaigns against the individuals that participated in that forum, whose name (#IronMarch) was used as a hashtag in their tweets.

Excerpt 4: This is the neo-Nazi user USERNAME from the #IronMarch forum, FIRSTNAME_LASTNAME (e-mail: USER@gmail.com). Since Nazis are cowards, he has locked his Twitter account.

The second category in terms of volume is that of hashtags associated with a geographical region. Most of them are cities in the US, although some states are also quoted. The third category of hashtags is those related directly to the target and usually consists in their first and last name. The fourth category of hashtag, always in terms of tweet volume, relates to political events. For example, in some of the doxing tweets, one finds hashtags be associated to the protests that followed the death of George Floyd (e.g., #blacklivesmatter or #kylerittenhouse).

Extract 5: First, we find FIRSTNAME_LASTNAME Uncle FIRSTNAME is a 58-year-old rough-looking resident of NEIGHBORHOOD_RESIDENCE who insulted and attacked #BlackLivesMatter counter-protesters at a “Back the Blue” rally in NEIGHBORHOOD_DEMONSTRATION on DATE_DEMONSTRATION.

The fifth and final category comprises hashtags referring to alt-right organisations (e.g., #proudboys). In addition to the categories of hashtags, the #threat was used in a similar proportion as the hashtags related to alt-right organisations.

Evidence

The fourth theme that emerges from the doxing tweets is the evidence provided by antifa users to support their claims. This topic is composed of the categories (a) Documents, (b) Cross-referencing of sources, and (c) Antifa websites and blogs.

Documents

Doxing means dropping documents, and antifa users disseminate documents of three different natures: images, hyperlinks and, less often, videos. The vast majority of shared documents did not require any form of hacking or infiltration; quite the contrary, they were obtained freely from the internet. We only found two instances in which antifa users mention or imply that they have stolen data on their target; but one should also consider the information available on the internet that have been obtained through data leaks, which is more common.

Images can be classified into two types: screenshots and photos, whose share is almost equal. Screenshots are representations of the activities of the target in the digital world, and two thirds of them were taken from the targets’ social networking accounts. They can consist, for example, on images of the target’s comments on a social network. The remaining screenshots originate from websites containing leaked data from various right-wing platforms, web pages or archived web pages, official documents, videos, and press articles.

The photos are representations of the target in the physical world. The vast majority consist of photos that the target has shared on social networks such as portrait photos or selfies. Occasionally they represent the targets in the places of their occupational activities, but often they can have political implications. Some represent the target in possession of firearms, or during political demonstrations, or making a sign of membership of an alt-right group or a racist sign such as a Nazi salute.

Antifa users also share hyperlinks. Most of them point to external websites such as social networks or web pages archived with the Waybackmachine service of Internet ArchiveFootnote 2 or other archiving services. The second most common type of hyperlinks leads to websites containing leaked data from right-wing forums. The third type leads the user to press articles that provide context to the doxing case. For example, a link to a news article that informs about previous illegal activities of a right-wing organisation member. The fourth type of hyperlink provides content about the target’s employer. It can lead, for example, to the employer’s Facebook page or website. Sometimes this website includes a contact page that the antifa user suggests should be used to denounce the doxing target to his or her employer.

More rarely, users share videos about the targets. Most of the videos associated with the tweets are introductory videos that the targets have sent to a local Proud Boys group in order to apply to join the group. In other instances, antifa users share links to YouTube videos that show the doxing targets.

Cross-Referencing of Sources

In a small number of tweets, antifa users mention their strategy to prove the involvement of the target. The proof is obtained by cross-referencing different data sources, as in a journalistic work. In the following example, antifa users link shared messages of a fascist user on an alt-right forum with information about his home address.

Extract 6: “USERNAME” wrote on StormfrontFootnote 3 that he is 7 h away from EVENT_PLACE, which corresponds to the address of FIRSTNAME_LASTNAME in STATE.

Antifa Websites and Blogs

Sharing hyperlinks that direct to blogs maintained by antifa or affiliated organisations is another method used by these users in their doxing efforts. On these blogs one can find information similar to that of the tweets, except that it is usually more precise and personal. For example, instead of sharing only the city of residence, as is the case with some tweets, the blog can indicate the target’s last known physical address (city, street name, street number and postcode). Sometimes, it is also possible to find the target’s last known mobile phone number or private e-mail address. This kind of information is not included in the tweets because it would violate Twitter’s terms of use. Antifa users are aware of the terms and conditions and on a few occasions in the corpus analysed, they mention that they have adapted the content published in their tweet to comply with the terms and conditions. The following example is a tweet in which the users redirect the user to a blog post about the target.

Excerpt 7: Launch of #panzerdox, the start of a series featuring the owners, supporters and customers of white supremacist clothing companies and their business platforms. @paypal @ecwid @facebook

In this article, you will find FIRSTNAME_LASTNAME1 and FIRSTNAME_LASTNAME2 from Panzer Street Wear. [URL_BLOG_ANTIFA]

Doxing Impact

The last topic concerns the impact of doxing both in terms of what antifa users would like to achieve (exploitation of the social reaction) and in terms of what they have achieved concretely (the consequences of doxing).

Exploitation of the Social Reaction

The exploitation of social reaction is a key element in antifa users’ doxing strategies. They aim to provoke a response that will negatively impact their targets. A common strategy is reaching out to the employers and educational institutions (e.g., schools, universities) affiliated with the target, as well as online professional services used by the targets. For instance, antifa users may question the employer or school about their acceptance or tolerance of the target’s political activism. In other instances, antifa users ask whether the person is employed at the company, while specifying that the target of doxing is a white supremacist or other forms of disreputable qualification. In the case of a non-response by an employer or another significant actor for the target, antifa users can persistently ask follow-up questions. As mentioned previously, antifa users may also submit a complaint to the employer or school about having the target as a member of their organisation.

Excerpt 8: UPDATE: We have just confirmed that the white supremacist podcast producer FIRSTNAME_LASTNAME is still employed by the STATE_EMPLOYER @EMPLOYER at LOCAL_EMPLOYER @EMPLOYER in CITY_ EMPLOYER, STATE_EMPLOYER. Let us see what LASTNAME has to say (insert TARGET_RECORDED_VIDEO). @EMPLOYER why do you employ this intolerant person?

Excerpt 9: Hi @EMPLOYEUR - It is a new week and you still have not clarified whether you are keeping the white nationalist propagandist FIRSTNAME_LASTNAME employed as a JOB_DESCRIPTION at #EMPLOYEUR. Do you think letting someone who calls black people “subhuman at best” work with CLIENT_TYPE is a good idea?

Excerpt 10: Hello LOCAL_EMPLOYER @EMPLOYER - It has been 3 weeks since we posted information about your white supremacist employee FIRSTNAME_LASTNAME. We have not received a response from you despite our follow-up questions. What is going on? @EMPLOYER @LOCALEMPLOYER

In other situations, antifa users contact platforms used by their targets. The procedure is the same used when employers or schools/universities are contacted, as they point out the moral dilemma of hosting right-wing content.

Excerpt 11: Hey @instagram! You host white supremacist Nazis FIRSTNAME_LASTNAME1 and FIRSTNAME_LASTNAME2 who use your services to mail order their merchandise from their Hitler-themed home in CITY_RESIDENCE. Does this seem normal to you?

The Consequences of Doxing

Occasionally, antifa users mention in their tweets the consequences of doxing. Targets will sometimes react by deleting their social network accounts or restricting access to them. Sometimes antifa users mention the professional difficulties faced by the targets, such as being dismissed from their jobs or having difficulties finding a new job. They also denounce the targets that use a social platform after having been banned from it.

Excerpt 12: Thanks to everyone who spread the word and helped report it, NAME’s online shop, which offered neo-Nazi tactical gear and propaganda (as well as social networking accounts), was shut down in less than 12 h! We look out for each other!

Towards a Grounded Theory of Doxing by Antifa Users

Some members of the antifa movement use doxing to attack alt-right activists and trigger a social reaction that will catalyse wider action against these activists. Considering the categories presented in the previous sections of this work, this chapter is devoted to the presentation of an explanatory theory of the phenomenon under study: doxing by adherents of the antifa social movement.

In that perspective, the practice of doxing by antifa users can be broken down into four stages: (1) finding out how dangerous the alt-right is and its adherents (2) collecting data on alt-right individual(s) and building a case to demonstrate their dangerousness (3) providing information about the target and (4) causing negative consequences on the target (Fig. 1).

From the dataset analysed, it appears that the danger posed by the alt-right is viewed as significant. This perception of danger seems to be the driving force behind the doxing actions undertaken by antifa users. In the tweets, this danger is manifested by the type of organisation whose members are targeted. These are alt-right organisations that are labelled by organisations like the SPLC as hate groups or anti-government groups. The threat associated with the alt-right and its adherents is deduced from the justifications put forward by antifa users. These show how their targets have a history of misbehaviour or adherence to alt-right groups or ideologies. Furthermore, the use of offensive or derogatory names indicates a desire to ostracise the targets from the rest of society. These names are frequently linked to terms used to describe right-wing extremists, such as neo-Nazi or racist.

Upon identifying the target, antifa users commence data collection. As they explained in their tweets, most of that data are obtained from open sources such as leaked hacked data or data shared by the targets on social media. Since targets can in some situations delete the original source of the data, antifa users perform data preservation work by uploading photos, taking screenshots or archiving web pages with services such as the Waybackmachine. Through this preservation work, antifa users build up their documents ready for publication (dropping). The information collected allow an indisputable identification of the targets as it includes their legal name, occupation, place of residence, internet pseudonyms, ages, and distinctive physical features.

The tweets analysed show that, in addition to collecting personal information about their targets, antifa users cross-reference various sources to show the dangerousness of the doxing target. This cross-referencing of sources and downloading of documents feeds into each other until a case is made about the target.

Following the identification of targets and building a case against them, antifa users proceed to denounce them on the internet and, in particular, via social media. This is when doxing (dropping documents) takes place. On Twitter, antifa users use several features of the social network to disseminate their message. Mentions are used to share the collection of documents with other antifa users who can in turn spread the message to their followers. Mentions are also used to alert employers, educational institutions and online platforms of their connection to the target. Sometimes, hashtags are also used to disseminate messages about the target on Twitter. These hashtags allow facilitate the several cases of doxing under one doxing campaign or to associate them with social struggles as in the case of #blacklivesmatter. In some cases, antifa users will ask their audience to participate, recommending that they contact the target’s entourage (employers or educational institutions) or to denounce the target for using the online services provided by some companies.

In their tweets, antifa users often redirect their audience to blogs and websites under their control. n these platforms beyond Twitter’s jurisdiction, antifa activists can share personal private information about their target without being sanctioned by Twitter for a breach of the terms and conditions. In addition to publicly exposing their target, antifa users attempt to exploit a social backlash to punish the target for their involvement in the alt-right.

Doxing aims to cause negative consequences on the target, which can sometimes be observed through the tweets of antifa users. Targets react by deleting or restricting access to their social network accounts. In other cases, antifa users mention professional difficulties faced by the target, such as being fired or having their account deleted on an online platform.

Discussion and Conclusion

As mentioned in the section dedicated to the review of the literature on doxing, previous research on this topic is scarce and emanates from other fields than criminology. Consequently, the comparison of our findings with those of previous studies can only be limited. In that perspective, Bray (2017) and Vysotsky (2020) posits that the raison d'être of the antifa social movement is to “fight” against the alt-right. Similarly, our findings suggest that the perceived threat of the alt-right is the main driver of doxing by antifa users. From a criminological perspective, it can be argued that the neutralisation techniques (Sykes & Matza, 1957) used by antifa activists to justify their actions are related to a perceived “need of defence” from the alt-right.

Some of our results align with research conducted on doxing by Lee (2020) and Snyder et al. (2017), namely the dehumanisation of the target and the fact that most of the targets are men. Nevertheless, our findings demonstrate that the reasons for antifa activists doxing practice are primarily political, while Snyder et al. (2017) detected political motivations in only 1.1% of their cases. The difference comes from the fact that the studies are not comparable in terms of the field of study, sample, and methodology. In a similar vein as in the study of Eckert & Metzger-Riftkin (2020), the antifa users in our sample collect digital evidence on their targets. They capture screenshots, upload photos from social networks and use Waybackmachine or other archiving services. In this way, the content shared by the right-wing targets is reappropriated by the doxers to incriminate them for their political activism (Lee, 2020). Following publication of this content, the typical reaction of the targets is to restrict the access to—or simply delete—their social media accounts. In our analyses we did not find any case of a target contesting the evidence presented in the doxing tweets. Similarly, we did not find any example of their educational institutions or employers defending them. Whenever, the employers intervened, their reaction was to terminate their contract with the target.

Douglas (2016) presents a taxonomy of three distinct forms of doxing. The first involves deanonymisation, in which doxers publicly release personal information that associates an individual to their previously anonymous persona. The second type of doxing, known as targeting doxing, pertains to the exposure of personal information that reveals details usually kept concealed or private. The final category, delegitimising doxing refers to the disclosure of intimate personal information capable of tarnishing an individual’s reputation. Although the author acknowledges the potential justification of doxing if it leads to the revelation of wrongdoings of public relevance, he asserts that revealing personal information that enables the harassment or intimidation of an individual is unwarranted and unethical. In this regard, most tweets gathered for our study could be classified as falling into the latter two categories. Specifically, many tweets engaged in targeting doxing by disclosing the victim’s personal information, such as their workplace, while others engaged in delegitimising doxing by making accusations that the target was affiliated with the alt-right movement.

Another compelling finding of our research, which coincides with the results of Lee (2020), is that antifa users disseminate hyperlinks as a minimisation strategy to limit their criminal liability. Antifa users adhere closely to Twitter’s terms and conditions, but incorporate hyperlinks to external antifa blogs and websites that hold sensitive information about the target that would be banned if shared on Twitter. Similarly, they use Twitter features such as mentions as a “call for action’ and hashtags as a way of disseminating the dropped documents, which coincides with the findings of Xu (2020). Antifa blogs and their content seem to be therefore a rich source for further research that delves into the details of doxing as well as searches to prevent this phenomenon from happening.

The alt-right represents a security-related danger (Jones et al., 2021; Jones & Doxsee, 2020), which materialised in the attack on the US Capitol on 6 January 2021 (Rapoport, 2021). Intelligence services and police forces could use the publications of antifa users as an additional surveillance tool, and are likely already doing so. The identification of individuals involved in right-wing extremism, the collection of data, the processing of data and the dissemination of information in the form of doxing are tasks already performed by antifa users. If these data were legally acquired, they could be used by the criminal justice system to prosecute potential illegal activities of alt-right activists even if it means concurrently prosecuting the unlawful actions of antifa users.

Conversely, the digital realm fosters an environment where individuals can be convicted without a trial and without guarantees for the accused, such as the presumption of innocence. However, this study cannot definitely ascertain the accuracy of doxing efforts undertaken by antifa activists, as this was beyond the scope of our research. In addition to the matter of accuracy, it should be noted that even when the information disclosed is not falsified, it is not necessarily the result of a thorough investigation. Therefore, the content disclosed by doxing campaigns may be taken out of context, as is often the case with selectively chosen posts or statements made by the target. Furthermore, there is a risk of targeting people who are not necessarily right-wing radicals. Since there is no legal definition of what constitutes the alt-right and antifa do not necessarily apply the legal definitions of what constitutes an illegal organisation, which means that sometimes people belonging to legal political parties could also be targeted and harassed by antifa activists. In addition, doxing might also facilitate other forms of victimisation. For example, targets may be harassed by a multitude of internet users as was the case for the victims of Gamergate (McIntyre, 2016) or be harassed on communication channels that are considered as private, such as their mobile phones (Douglas, 2016), or outside the digital sphere (Douglas, 2016). In these cases, the consequences of doxing go far beyond those of its offline predecessor, gossiping. In fact, sometimes doxing can be compared to an online contemporary form of vigilantism and entails similar risks. For this reason, and regardless of the disdain that we experiment towards fascist positions, we consider that the authorities of the criminal justice system are obliged to intervene to guarantee the constitutional and human rights of the targets and provide them a fair trial if they have engaged in illegal activities.

Before concluding, several limitations of our study should be noted. First, it relies on a list of users established through the subscriptions of a notable antifa activist, but that list is necessarily uncomplete, which means that it may have excluded other users actively involved in doxing, or it could have been outdated. Second, during the process of coding, we included all the tweets in which the legal name of the target was mentioned. This could have artificially inflated the number of times the person’s legal name is mentioned; but it is also true that the legal name or at least the first name of the target is frequently mentioned in the tweets, which suggests that the increase should not be significant. Third, sampling English-language publications restricts the possibility of comparing doxing across countries. As the antifa movement is well established in Germany (Bray, 2017), it would be interesting to study the practices of these German-speaking groups. Forth, the social network Twitter imposes certain limits on the content that can be published. Therefore, relying on the data produced on this social network does not allow us to capture the full dimensions of doxing. To access other relevant data, examining the content published on websites and other social networks used by these groups would be worthwhile.

In sum, the antifa social movement is a countermovement whose main objective is to defeat all forms of political mobilisation of the alt-right. Ideologically inspired by anarchist philosophy, the proponents of the antifa movement use several forms of direct action against their political opponents. Doxing is part of their repertoire of action. Information gathering, cross-referencing and dossier building are used to “build a case” against doxing targets. Then, antifa activists unveil their information on Twitter, making use of several features of the platform to disseminate their message to fellow antifa users, organisations related to the doxing target (e.g., employers) and their audience. To substantiate their accusations, antifa users use documents (e.g., images) that “prove” the implication of the target in the alt-right. By doxing their targets, antifa users aim to raise the cost of political activism for far-right activists in the hope of demobilising them. Further research should shed light on the harms that doxing causes, on antifa websites that publish content banned on Twitter, on the use of “intelligence” gathering by antifa activists for law enforcement agencies, as well as on the cross-country comparison of doxing, namely with Germany.

Notes

Link to web page for downloading TWINT script: https://github.com/twintproject/twint/

The Waybackmachine service allows an Internet user to save the state of a web page at a given time and make this backup available to other Internet users (Internet Archive, 2019).

Stormfront is a far-right forum (SPLC, n.d.-c).

References

Alvesson, M., & Skoldberg, K. (2009). Reflexive methodology: New vistas for qualitative research. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Bateson, R. (2021). The politics of vigilantism. Comparative Political Studies, 54(6), 923–955. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414020957692

Bray, M. (2017). Antifa: The anti-fascist handbook. Melville House.

Burley, S. (2017). Fascism today: What it is and how to end it. AK Press.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. SAGE Publications Inc.

Chen, Q., Chan, K. L., & Cheung, A. S. Y. (2018). Doxing victimization and emotional problems among secondary school students in Hong Kong. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(12), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122665

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2007). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Sage.

DeCook, J. R. (2018). Memes and symbolic violence: #proudboys and the use of memes for propaganda and the construction of collective identity. Learning, Media and Technology, 43(4), 485–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2018.1544149

Douglas, D. M. (2016). Doxing: A conceptual analysis. Ethics and Information Technology, 18(3), 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-016-9406-0

Douglas, D. M. (2020). Doxing as audience vigilantism against hate speech. In D. Trottier, R. Gabdulhakov, & Q. Huang (Eds.), Introducing vigilant audiences (Open Book Publishers, pp. 259–279).

Dunbar, R. I. M. (2004). Gossip in evolutionary perspective. Review of General Psychology, 8(2), 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.100

Eckert, S., & Metzger-Riftkin, J. (2020). Doxxing, privacy and gendered harassment. The shock and normalization of veillance cultures. M&K Medien & Kommunikationswissenschaft, 68(3), 273–287.

Engward, H., & Davis, G. (2015). Being reflexive in qualitative grounded theory: Discussion and application of a model of reflexivity. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(7), 1530–1538. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12653

Feuer, A. (2021). Did the proud boys help coordinate the capitol riot? Yes, U.S. suggests. The New York Times. Retrieved November 8, 2021, from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/05/nyregion/proud-boys-capitol-riot-conspiracy.html

Garson, G. D. (2016). Grounded theory. Statistical Associates Publishers.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Transaction.

Heikkilä, N. (2017). Online antagonism of the alt-right in the 2016 election. European Journal of American Studies, 12(12–2), 2. https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.12140

Hutchison, A. J., Johnston, L. H., & Breckon, J. D. (2010). Using QSR-NVivo to facilitate the development of a grounded theory project : An account of a worked example. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 13(4), 283–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570902996301

Internet Archive. (2019). Wayback machine general information. Internet Archive Help Center. Retrieved November 8, 2021, from https://help.archive.org/hc/en-us/articles/360004716091-Wayback-Machine-General-Information

Inwood, J. (2019). White supremacy, white counter-revolutionary politics, and the rise of Donald Trump. Environment and Planning c: Politics and Space, 37(4), 579–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654418789949

Jones, S. G., & Doxsee, C. (2020). The war comes home: The evolution of domestic terrorism in the United States. In Center for strategic and international studies. Retrieved December 18, 2021, from https://www.csis.org/analysis/war-comes-home-evolutiondomestic-terrorism-united-states

Jones, S. G., Doxsee, C., & Hwang, G. (2021). The military, police, and the rise of terrorism in the United States (p. 15). Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved December 24, 2021, from https://www.csis.org/analysis/military-police-and-riseterrorism-united-states

Jones, B. (2020). Cyber creeps: The alt-right and the evolution of social media hatemakers. In J. Jones & M. Trice (Eds.), Platforms, Protests, and the Challenge of Networked Democracy (pp. 117–134). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36525-7_7

Klein, A. (2019). From twitter to Charlottesville: Analyzing the fighting words between the alt-right and antifa. International Journal of Communication, 13(0), 0.

Lee, C. (2020). Doxxing as discursive action in a social movement. Critical Discourse Studies, 0(0), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2020.1852093

March, E., & Marrington, J. (2019). A qualitative analysis of internet trolling. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0210

McIntyre, V. (2016). ‘Do(x) you really want to hurt me?’: Adapting IIED as a solution to doxing by reshaping intent. Tulane Journal of Technology & Intellectual Property, 19, 111–133 https://journals.tulane.edu/TIP/article/view/2667

Neumayer, C., & Valtysson, B. (2013). Tweet against Nazis? Twitter, power, and networked publics in anti-fascist protests. MedieKultur: Journal of Media and Communication Research, 29(55), 55. https://doi.org/10.7146/mediekultur.v29i55.7905

Nuernbergk, C. (2015). Nationalist and anti-fascist movements in social media. Routledge.

Rampell, C. (2017). Opinion | Trump’s lasting legacy is to embolden an entirely new generation of racists. The Washington Post. Retrieved February 8, 2022, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/racism-isnt-dying-out/2017/08/14/058cefc8-812d-11e7-b359-15a3617c767b_story.html

Rapoport, D. C. (2021). The capitol attack and the 5th terrorism wave. Terrorism and Political Violence, 33(5), 912–916. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2021.1932338

Smallridge, J., Wagner, P., & Crowl, J. N. (2016). Understanding cyber-vigilantism : A conceptual framework. Journal of Theoretical & Philosophical Criminology, 8, 57–70 https://calio.dspacedirect.org/handle/11212/2958

Snyder, P., Doerfler, P., Kanich, C., & McCoy, D. (2017). Fifteen minutes of unwanted fame: Detecting and characterizing doxing. In Association for Computing Machinery (Ed.). Proceedings of the 2017 Internet Measurement Conference (pp. 432–444).The Association for Computing Machinery https://doi.org/10.1145/3131365.3131385

Southern Poverty Law Center, (2021). Who are boogaloos, who were visible at the capitol and later rallies? Southern Poverty Law Center. https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2021/01/27/who-are-boogaloos-who-were-visible-capitol-and-later-rallies

Southern Poverty Law Center, (n.d.-a). Alt-right. Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved 5 January 2021, from https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/ideology/alt-right

Southern Poverty Law Center, (n.d.-b). Groups. Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved 1 December 2021, from https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/groups

Southern Poverty Law Center, (n.d.-c). Stormfront. Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved 24 November 2021, from https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/group/stormfront

Southern Poverty Law Center, (n.d.-d). What we do. Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved 5 January 2021, from https://www.splcenter.org/what-we-do

Sykes, G. M., & Matza, D. (1957). Techniques of neutralization: A theory of delinquency. American Sociological Review, 22(6), 664–670. https://doi.org/10.2307/2089195. JSTOR.

Twitter. (2020). Conditions d’utilisation de Twitter. Retrieved September 8, 2021, from https://twitter.com/fr/tos/previous/version_15

Vysotsky, S. (2020). American antifa: The tactics, culture, and practice of militant antifascism. Routledge.

Wilson, J. (2019). Leak from neo-Nazi site could identify hundreds of extremists worldwide. The Guardian. Retrieved November 4, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/nov/07/neo-nazi-site-iron-march-materials-leak

Xu, W. W. (2020). Mapping connective actions in the global alt-right and antifa counterpublics. International Journal of Communication, 14(0), 0.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Yuji Z. Hashimoto and the anonymous reviewers for their support and useful remarks on earlier versions of this manuscript. They also thank their colleagues from the School of Criminal Sciences at the University of Lausanne for their support.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Lausanne The authors received no financial support for the research, drafting of the manuscript or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Planification of the research: L. Molnar, L. Jaccoud & M. F. Aebi; data collection and analysis: L. Jaccoud; preparation of the manuscript: L. Jaccoud; edition and revision of the manuscript: L. Molnar & M. F. Aebi.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jaccoud, L., Molnar, L. & Aebi, M.F. Antifa’s Political Violence on Twitter: a Grounded Theory Approach. Eur J Crim Policy Res 29, 495–513 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-023-09558-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-023-09558-6