Abstract

Prejudice and bias-motivated aggression (BMA) are pervasive social problems. Scholars have tested numerous competing theoretical models to demonstrate the key predicates of prejudice and BMA, including intergroup contact, dual process (i.e., right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation), perceived injustice, peer socialization, and empathy. Yet, studies to date have not empirically examined the comparative strength of these theoretical perspectives to explain the correlates of (a) prejudice and (b) BMA. This study seeks to address this gap. Utilizing a sample of young 1,001 Belgian participants, this study explores the association between key constructs from different theoretical perspectives to better understand prejudice and BMA towards immigrant populations. Findings show that when accounting for all models of prejudice and BMA, the strongest predictors of prejudice emerge from the dual-process model, the empathy model (outgroup empathy), and the quality (not frequency) of intergroup contact. Yet, prejudice and exposure to peer outgroup hostility are the strongest predictors of BMA. We discuss the implications of our findings and suggest that drawing on criminological theories of prejudice and BMA can be integrated to provide a more nuanced understanding of the nature of prejudice and BMA than what is currently known. We conclude by highlighting some directions for future research on prejudice and BMA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intergroup relations between majority and minority groups have become a key area of research, due in large part to the increasing diversity of national populations and the rise in immigration rates (Sibley et al., 2013). Migratory flows have also become a topic of social and political debate, with right-wing political parties exploiting the perceived threat that immigration poses to secure public support for their policies (Craig & Richeson, 2014). These issues and their associated rhetoric are important for understanding the formation of and mechanisms affecting individuals’ prejudicial attitudes towards immigrants and their propensity to engage in bias-motivated aggression (BMA).

Prejudice denotes the formation of discreditable beliefs or judgments towards an individual or group. Prejudice is often dissected into blatant and subtle forms. The former is more overt and often manifests as a “perceived threat from and rejection of the outgroup,” whereby prejudiced individuals avoid contact with those they view as an outgroup member (Pettigrew & Meertens, 1995, p. 58). The latter is more covert and sees prejudiced individuals defending their ingroup’s traditional values and emphasizing cultural differences that distinguish ingroup members from outgroup members (Pettigrew & Meertens, 1995).

If nurtured, prejudice can have harmful implications (Durrheim et al., 2016). For example, prejudice towards immigrants can create bias in the criminal justice system (Holmberg & Kyvsgaard, 2003) and in some instances, mobilize hatred and aggression (Durrheim et al., 2016). The latter can manifest as BMA, whereby a perpetrator targets their victim because of their actual or perceived membership within a group. The focus here is on intergroup aggression directed towards perceived outgroup members (Schmid et al., 2014). In the context of the present study, we examine the predicates of prejudice and BMA towards immigrant groups as the perceived outgroup. Prior research has focused on the predicates of prejudice. Yet, as prejudicial attitudes can have potentially dangerous effects (e.g., aggression), understanding the factors that shape prejudice towards immigrants and the likelihood to engage in BMA is critical to addressing this problem (see also Schmid et al., 2014).

A large body of research has examined the predicates and consequences of anti-immigrant prejudice (see e.g., Cohrs & Stelzl, 2010; Pettigrew, 1998; Sibley et al., 2013) and BMA (Faragó et al., 2019; Schmid et al., 2014; Thomsen et al., 2008) separately. Prior studies show that theories including social dominance orientation (SDO) and right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) (Thomsen et al., 2008), as well as perceived injustice (Doosje et al., 2012) and intergroup contact (Pettigrew et al., 2011; Schmid et al., 2014), strongly and independently predict anti-immigrant prejudice and aggression. Yet, few studies have tested the potentially interrelated nature of these factors in influencing both attitudes and behaviors (Sibley et al., 2013). Arguably, an integrated approach can account for the individual- and situational-level correlates of bias-motivated attitudes and behavioral intentions (Sibley et al., 2013). However, prior to testing an integrated model, determining the relative effect of these widely used theories of prejudice and BMA is necessary. As such, this study seeks to spotlight the strongest predictors of prejudice and BMA that may give rise to theoretical integration.

Finally, this study also compares the predicates of prejudice and BMA on a sample of young people. This may provide important information to promote attitudinal and behavioral change given that socialization processes occur and are more malleable to change at a young age (Tyler & Trinkner, 2017). Moreover, studies show that youths and young adults are sensitive and impressionable to external stimuli, which can shape their attitudes and behaviors (Gwon & Jeong, 2018; Schröder et al., 2022). Thus, comparing theoretical models of prejudice and BMA on a younger sample may not only elucidate the factors that can contribute to a young person’s likelihood of harboring prejudicial attitudes or behavioral intentions, but also how they can be assuaged.

The Contact Hypothesis, Prejudice, and Bias-Motivated Aggression

Allport’s (1954) landmark contact hypothesis provides a basis for understanding how prejudice can be formed and alleviated. The contact hypothesis is predicated on the notion that cooperative contact with a member(s) of a negatively stereotyped social group might (a) ameliorate specific and harmful attitudes towards those member(s) and (b) generalize to less negative attitudes toward the group as a whole (Allport, 1954; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). In recent years, the contact hypothesis has been subject to numerous tests, meta-analyses (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006; Zhou et al., 2019) and revisions (Paluck et al., 2019). In their meta-analysis, Pettigrew and Tropp (2006) suggest that three important elements pertinent to the intergroup contact framework can reduce prejudicial attitudes: (1) enhancing knowledge about the outgroup, (2) reducing anxiety about intergroup contact, and (3) increasing empathy and perspective taking. Taken together, studies demonstrate that direct contact with outgroup members can alleviate prejudiced attitudes (Pettigrew et al., 2011) and diminish the likelihood to engage in aggressive behaviors (Schmid et al., 2014).

Prior research has also demonstrated the importance of the qualitative difference between the quality and frequency of contact (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). Johnston and Glasford (2018, p. 1186) distinguish the two by suggesting that “quality contact addresses the degree to which contact is positive and cooperative, whereas frequency contact involves the frequency with which a person comes into contact with an outgroup.” However, in examining both types of contact, research across differing contexts has found that the quality of contact, rather than the frequency, is linked to numerous positive outcomes. These include a greater propensity to intervene on behalf of an outgroup (Abbott & Cameron, 2014), more positive intergroup relationships (e.g., Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006), and a stronger inclination to help outgroup members (Johnston & Glasford, 2018). As such, while we include both types of contact in our study to determine the relative importance of contact quality and the frequency of intergroup contact, we expect to see a significant relationship only with contact quality.

The Dual-Process Model, Prejudice, and Bias-Motivated Aggression

Prejudice scholars have also focused on the explanatory value of RWA and SDO. Both RWA and SDO are centered around an individual’s specific worldviews and personality traits. RWA refers to a belief in the world as dangerous and threatening, accompanied by a desire for strong leaders and clear and effective enforcement of norms to avoid the dissolution of group cohesion (e.g., Altemeyer & Altemeyer, 1981; Asbrock et al., 2010; Duckitt, 2006). SDO, alternatively, is premised on harboring a competitive worldview and favoring hierarchical structures so that superordinate groups can control subordinate ones (Duckitt, 2006; Pratto et al., 2006). Contrary to RWA, social dominance does not reflect a desire for group cohesiveness, but rather a self-oriented need for power. Both SDO and RWA are part of the dual-process model of prejudice (Duckitt, 2006).

The worldviews shaped by RWA and SDO are underpinned by threat perceptions (Matthews et al., 2009). Those who align with RWA and/or SDO values are more likely to view outgroups as a threat and subsequently, hold more prejudicial beliefs (Duckitt, 2006). Studies confirm the strength of RWA and SDO in predicting prejudice (e.g., Altemeyer, 1998; Duckitt, 2006). Additionally, both RWA and SDO have been associated with the justification of violence and aggression (see e.g., Cohrs & Stelzl, 2010; Esses & Hodson, 2006; Thomsen et al., 2008). These studies suggest that when outgroups are perceived as threatening—albeit for different reasons—the desire by ingroup members to utilize aggression to defend their group is heightened.

Perceived Injustice, Prejudice, and Bias-Motivated Aggression

Perceived injustice (sometimes termed “grievances”) refers to a sense of unfair treatment and is a widely studied concept in research on violent extremism and political violence in adolescents (e.g., Doosje et al., 2012; Pauwels & Schils, 2016; Williamson et al., 2021). Perceived injustice is often seen as a mechanism that can trigger violent (extremist) norms, because the perception of unfairness or deprivation can create feelings of anger and frustration (Moghaddam, 2005). Agnew’s General Strain Theory (GST) provides a relevant framework for understanding how perceived injustice, prejudice and BMA may be interlinked. GST posits that negative feelings may cause strain, which can create the conditions for deviant attitudes or behavior to materialize by stimulating negative emotions and support for violence (Agnew, 2006). Perceived injustice as a type of strain can manifest from numerous sources, including economic, social, or political conditions, or threats to one’s group-based identity (Moghaddam, 2005). At the inter-group level, one’s perception that their group is disenfranchised relative to others may create the conditions for prejudicial attitudes to flourish. Relatedly, research shows that one’s perceptions that their group is unjustly treated is associated with violent beliefs (Pauwels et al., 2020) and behavioral intentions (Daskin, 2016). In this way, outgroups deemed “responsible” for the injustices perceived by members of an ingroup are more likely to become the target of violence and aggression (Daskin, 2016).

Peer Socialization, Prejudice, and Bias-Motivated Aggression

Finally, an empirical understanding of prejudice and BMA would be incomplete without accounting for the influence of an individual’s social networks. Socialization processes are critical to the formation of an individual’s attitudes and behaviors (Tyler & Trinkner, 2017). Peers are considered important agents of socialization, especially during adolescence. From a social learning perspective (including cultural evolution), an individual’s association with peers who harbor potentially harmful views, such as anti-social, criminogenic, or racist attitudes (i.e., prejudice), may influence one’s own attitudes and behaviors (Hoeben et al., 2021). In general, peer socialization is one of the strongest covariates of juvenile delinquency and violence.

The relationship between peer influences, prejudicial attitudes, and violence has been identified in prior research. For example, in two studies involving different samples of young people living in Belgium, Pauwels and colleagues (2014; 2016) found that participants’ associations with racist peers shaped their attitudes towards members of racial and/or ethnic minority groups and heightened their support for right-wing extremist ideals, which further perpetuated these racist notions. Despite these findings, research on how peers influence BMA is scarce compared to the contact hypothesis (Barkin et al., 2001). Existing research shows that the relationship between exposure to extremist peers and support for extremism is weaker than the relationship between exposure to peer delinquency and support for extremism (see e.g., Lösel et al., 2018; Wolfowicz et al., 2020). Similar findings are also observable in the context of self-reported acts of extremism (Pauwels & Schils, 2016). Measurement issues and theoretical misspecifications may contribute to this inconsistency. In the present study, we consider the role of exposure to peer outgroup hostility as a potential explanatory factor to understand BMA.

Empathy, Prejudice, and Bias-Motivated Aggression

In addition to including measures that may explain individuals’ prejudicial attitudes and propensity to engage in BMA, we also seek to examine the potentially mitigating role of empathy. Empathy is one example of how hostility, prejudice, and aggression towards a perceived outgroup can be reduced (Kenworthy et al., 2005). Despite definitional cloudiness (Davis, 1980), an evolutionary perspective may provide relevant insights into the relationship between empathy, prejudice, and BMA. Over time, humans have benefitted from their ability to formulate and cooperate within groups. The evolution of this “group psychology” includes a propensity to (i) identify with groups and its members, (ii) empathize with group members’ needs and interests; (iii) self-sacrifice, trust, and cooperate with other group members; and (iv) loyally commit and contribute to the functioning of one’s group (De Dreu & Kret, 2016).

Empathy has been shown to reduce the psychological distance a prejudiced person places between themselves and the target of their prejudice (Finlay & Stephan, 2000). The nature and extent of one’s empathy is contingent on their social context, and as social contexts are dynamic, empathy is malleable to change (Nezlek et al., 2001). For example, some studies have found that empathy is negatively correlated with prejudice in children and adolescents (see, e.g., Beelmann & Heinemann, 2014), and adults (see e.g., Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006), thereby suggesting that across age groups, more empathic individuals harbor less prejudiced attitudes. Yet in contrast, others find that empathy has a limited effect on perceptions of prejudice when also considering factors such as one’s ideological preferences (e.g., RWA) (Sidanius et al., 2013) or the presence of competitive contexts (e.g., SDO) (Diekhof et al., 2014). Empathy may therefore have a differential effect depending on one’s group identification, values, beliefs, and social norms (Miklikowska, 2018).

In the context of aggressive behaviors, several schools of thought explain the relationship between empathy and aggression. For example, control theories of crime postulate that empathy can act as a form of internal control whereby the more empathic an individual is, the less likely they will be to engage in aggression, and vice versa (Vachon et al., 2014). When considered from a learning theory perspective, empathic individuals are more likely to feel that their own aggressive behaviors vicariously punish a perceived outgroup member (Vachon et al., 2014). Prior research has found empathy to be a key factor in preventing and diminishing the likelihood of aggression more generally (Miller & Eisenberg, 1988) and in specific contexts, such as reducing aggression towards racial outgroups (Cikara et al., 2011). In this study, we compare the effects of ingroup and outgroup empathy. While ingroup empathy refers to one’s more positive views of and concern for their fellow ingroup members, outgroup empathy focuses on an individual’s sympathy towards the experiences of perceived outgroup members (Stephan & Finlay, 1999).

The Current Study

This study compares the effects of several well-known theoretical frameworks employed to understand prejudice and aggression: the contact hypothesis, the dual-process model (i.e., SDO and RWA), the role of perceived injustice, exposure to peer outgroup hostility, and ingroup and outgroup empathy. Theory comparison has been heavily promoted by different scholars because findings testing one theory can spotlight problems in other existing theories (Opp & Wippler, 1990). In this study, we compare several theories by examining the strength of their capacity to explain individual differences in prejudicial attitudes and self-reported BMA. Based on the literature presented in the previous section, the following hypotheses will be tested:

-

H1 To test the contact hypothesis, we expect that the quality rather than the frequency of intergroup contacts will be positively associated with prejudice and BMA.

-

H2 To test the dual-process model, we expect that RWA and SDO will be positively associated with prejudice and BMA.

-

H3 To test the perceived injustice model, we expect that perceived injustice will be positively associated with prejudice and BMA.

-

H4 To test the peer socialization model, we expect that (a) exposure to peer outgroup hostility will be positively associated with prejudice, and (b) prejudice and exposure to peer outgroup hostility will be positively associated with BMA.

-

H5 To test the empathy model, we expect that (a) outgroup empathy will be negatively associated and (b) ingroup empathy will be positively associated with prejudice and BMA.

Finally, all direct effects will be studied concurrently to understand the correlates of prejudice and self-reported BMA. As this final model is exploratory, we do not have any hypotheses to anticipate which direct effects will survive.

Methods

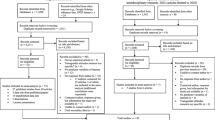

The present study utilizes survey data from a convenience cross-sectional sample of 1,001 students aged 17–25 years old living in Belgium. The original sample included participants ranging in age from 17 to 71; however, as the intent of the present study is to examine prejudice and BMA from the perspective of young people, all participants above the age of 25 and those of an immigrant background were omitted from the analyses (n = 155). Additionally, all participants who did not fully complete the survey were removed from the dataset (n = 144), leaving a final usable sample of 1,001 participants. The final sample had an average age of 21.07 years old (SD = 1.95) and comprised 36% males.

The survey was imputed to the Limesurvey platform and disseminated to potential participants via student mailing lists with an invitation to complete the survey. A reminder was sent 1 month after the original invitation was sent to encourage participation in the survey. The estimated completion time was 15 min. The survey was fielded in Dutch to students in several Belgian universities (Ghent University, University of Brussels, University of Hasselt, and University College Ghent) (Heylen, 2015).

Student samples are commonly drawn upon to conduct research in psychology (Goodwin & Goodwin, 2016), and can offer important insights into young people’s attitudes towards specific phenomena. This is particularly important when examining the antecedents of prejudice and BMA, which are often more likely to form from a younger age (Gwon & Jeong, 2018). However, convenience samples have their limitations, especially regarding external validity, and specifically when considering student convenience samples (see e.g., Peterson & Merunka, 2014). Representative surveys are often assumed to score higher on external validity, but this is only true to the extent that one has insight into the major forms of measurement error. Often, nonresponse is high. Survey data quality thus remains an important challenge in survey research more generally, regardless of topic or sample, as unknown sources of bias will always exist. Therefore, future research should always consider combining different strategies to keep measurement error as low as possible and to gain insight into the sources and magnitude of biases.

It is also important to stress that comparing the effects of key variables from different theoretical models is not without criticism. Indeed, no single theory can be said to “own” variables of a theoretical model. On the contrary, differences exist at the conceptual and empirical level: one variable can play a role in one theory and may play a different role in another. We do not want to reduce complex theories to “variables” as has been done in many early comparative tests of (etiological) theories. Theoretical integration is much more complicated than just comparing key variables. Our goal is simply to gain insight into the strengths of different concepts, as these concepts are often discussed in criminal policy and crime prevention. While we are fully aware of the fact that it is impossible to make strong conclusions on the determinants of BMA, this remains an important or non-negligible step in the process of scientific discovery and the evaluation of theories.

Measures

All key constructs are measured using scales. Most scales used in the present study (except otherwise explained) are Dutch translations of well-known and established scales used in social psychological research, but slightly modified to increase the content validity of the constructs within the framework of the present research (i.e., tailored to fit BMA towards members of an outgroup based on their ethnic background). In complex societies, individuals are members of different groups, thus determining what is an outgroup is not easy. However, in line with extensive research on attitudes and behaviors towards immigrants, we operationalize outgroups in a way that refers to the ethnic background of the outgroup. In the Belgian context, often immigrants with Turkish and/or Moroccan descent are studied, as these minorities are well represented in Belgium. Other scales were developed by Heylen (2015) as a part of a PhD study. These scales were carefully constructed, based on the principles of content validity, correlational validity, and internal consistency. These scales were also tested in a pilot study to gain insight into the factor loadings and reliabilities of the scales and the correlational validity of the constructs. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between all variables are presented in Appendix 1. All scale scores are standardized to compare their relative effect. Unless specified, all scale items are measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from completely disagree (1) to completely agree (5) (see Appendix 2 for the wording of all items and the factor loadings of all items in each scale).

Dependent Variables

Prejudice

The prejudice scale is based on Pettigrew and Meerten’s (1995) work on subtle and blatant prejudice. The only difference is that this study defines the outgroup as an individual with “Turkish/Moroccan descent.” The underlying attitudes are exactly the same attitudes that were used in the original scale. An overall scale is used (α = 0.90), combining eight items that measure subtle prejudice (α = 0.86) and six items that measure blatant prejudice (α = 0.80). A higher score on this scale indicates greater perceived prejudice.

Bias-Motivated Aggression

BMA is treated as a total frequency index. This scale was developed by Heylen (2015). This index is measured by combining participants’ responses to questions about their engagement in conduct that measures negative behavioral tendencies towards immigrants (an example question is Have you ever had negative feelings towards immigrants (e.g., fear, aversion, anger,…) and the frequency of their engagement in such activities in the 12 months prior to completing the survey. Answer categories ranged from 0 times (0) to more than 10 times (7). A higher score in this index indicates more frequent self-reported BMA. In self-reported delinquency research, different ways to operationalize the key dependent variable are used; the most often used variables are variety scales and total frequency scales (for a discussion see Menard et al., 2016). The items refer to a wide range of past behavioral tendencies.Footnote 1 A general variety refers to the number of different acts one reports to have been involved in, while the total frequency measure refers to the combination of the number of times a participant reports a specific act. There are both theoretical and methodological reasons to prefer one specific type of scale. From a theoretical point of view, the researcher’s decision is often guided by the versatility principle (i.e., offenders are on average rather versatile), so it is seen as a valid way to conduct analyses based on a general scale. On the other hand, subscales can be used to analyze whether the same pattern arises in regression models based on specific scales (e.g., serious offending scales). We have based our decision to present the results of the total frequency scale on the fact that both scales (variety index and total frequency index) are extremely high correlated (r = 0.75, p < 0.001). The results of the multiple regression models do not differ substantively. While a great deal of knowledge is available on the pros and cons of delinquency scales, such research is largely absent in studies of violent extremism, hate crime, or BMA in general. This topic deserves further methodological inquiry in criminological studies.

Independent Variables

Contact Quality and Contact Frequency

Contact is measured through a 7-item scale that includes indicators of the quality (α = 0.86) and frequency (α = 0.83) of contact. The items were adapted from the work of Pettigrew (1997). Specifically, items were adapted to ask participants about their contact with immigrant groups from Turkey and Morocco (who constitute large minority groups in Belgium as discussed above). A higher score on contact quality indicates a greater level of high-quality contacts (as perceived by the participant) and a higher score on contact frequency refers to a higher frequency of contact. As can be seen in Appendix 1, contact quality and contact quantity are moderately correlated (r = 0.35, p < 0.001).

RWA

RWA is measured through an 11-item scale measuring authoritarian aggression, conventionalism, and authoritarian submission (see Van Hiel & De Clercq, 2009) (α = 0.76). A higher score indicates that the participant had stronger self-reported RWA.

SDO

SDO comprises a 16-item scale (Duckitt & Sibley, 2007) (α = 0.92). A higher score indicates that the participant had stronger self-reported SDO.

Perceived Injustice

Perceived injustice is measured through an 8-item scale, comprising items referring to personal (α = 0.84) and group-related grievances (α = 0.89). The subscales were derived from a previous study of violent extremism (see Pauwels & Heylen, 2020). An exploratory factor analysis revealed that the items comprising both perceived personal and group injustice loaded onto one single factor; thus, a combined scale was used (α = 0.91).

Exposure to Peer Outgroup Hostility

Exposure to peer outgroup hostility is measured through 11 items that gauge peer involvement in outgroup hostility, ranging from feeling uncomfortable and having negative feelings to avoiding immigrants and stealing from immigrants. Items were developed for the purposes of the survey by Heylen (2015). Each item was measured on a 5-point scale ranging from none (1) to almost all peers (5), with a higher score representing a greater self-reported exposure to peer outgroup hostility (α = 0.82).

Empathy

Empathy is measured using 14 items derived from Davis’ (1980) seminal work but modified to distinguish empathy towards immigrant populations (i.e., the perceived outgroup) versus ingroup members. This enables an examination of outgroup empathy (α = 0.86) versus ingroup empathy (α = 0.79) (i.e., “local” or “parochial” empathy). A higher score indicates stronger levels of empathy.

Results

Two different regression analyses were conducted using the SPSS v.26 statistical program to measure the independent effects of the theoretical constructs on the two dependent variables of interest. Specifically, ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models with robust standard errors were used to examine the predictors of prejudice, and negative binomial regression models were conducted to test the predicates of BMA. Given the skewness of the BMA frequency scale, a negative binomial distribution fit the data best. Robust standard errors were used across all models because of the skewness of the prejudice scale and because of problems with heteroscedasticity (as indicated by White’s test; Long & Ervin, 2000). First, each theoretical model was tested individually (controlling for biological sex), which resulted in five models. Sex was the only control variable, as all participants were of Belgian descentFootnote 2 and age hardly varied. Finally, all variables were entered into one equation, which is a standard approach to comparing theories.

Model 1: Predicting Prejudice

The results of the first regression are presented in Table 1. Model 1 shows the intergroup contact model, which explained 41.9% of the variance in the model. Sex was not statistically significant in this model. Intergroup contact quality was strongly and negatively associated with prejudice (β = − 0.618; p < 0.001), while the relationship between the frequency of contacts and prejudice was small and negative (β = − 0.059; p < 0.05; Hypothesis 1 supported). These findings highlight the importance of the quality more than the frequency of intergroup interactions. Model 2 shows the findings of the dual-process model (RWA and SDO), which explained 57.3% of the individual differences in prejudice. When the dual-process variables were entered into the equation, the sex variable was no longer significant. Both RWA (β = 0.345; p < 0.001) and SDO (β = 0.523; p < 0.001) were positively associated with prejudice, with SDO having the strongest association (Hypothesis 2 supported). These findings indicate that the dual-process model is important for understanding perceptions of prejudice. Model 3 shows the results for the perceived injustice model, which explained 5.3% of the variance in the model. Perceived injustice was positively associated with prejudice (β = 0.215, p < 0.001) when controlling for sex (β = 0.129; p < 0.05), suggesting that perceptions of injustice increase the likelihood of prejudicial attitudes amongst our sample (Hypothesis 3 supported). Model 4 shows the results for the peer socialization model, which explained only 3.6% of the individual differences in prejudice. Exposure to peer outgroup hostility was positively associated with prejudice (β = 0.168; p < 0.001; Hypothesis 4 supported), suggesting that those who socialized with individuals who held hostile views towards perceived outgroup members were more likely to express prejudicial views. The empathy model (Model 5) performed well, explaining 53.3% of variance in the model. Specifically, outgroup empathy was strongly and negatively associated with prejudice (β = − 0.775; p < 0.001) while ingroup empathy had a small and positive association (β = 0.113; p < 0.001; Hypothesis 5 supported). These results point to the potentially protective nature of empathy in mitigating prejudicial attitudes towards perceived outgroups.

Finally, a model was run to examine the relationship between all variables from the different theoretical perspectives and prejudicial attitudes (see Model 6). This model explained 74.2% of the variance in the model, which justifies the need to develop an integrated model. Of the variables from the intergroup contact hypothesis, only contact quality remained significant (β = − 0.224; p < 0.001), suggesting that the quality of contact a participant has with a perceived outgroup member can go some way in reducing the likelihood of harboring prejudicial views. The dual-process model was more strongly and positively associated with prejudice (RWA: β = 0.251; p < 0.001; SDO: β = 0.257; p < 0.001), while the effect of perceived injustice was very small (β = 0.040; p < 0.001). Exposure to peer outgroup hostility was not significantly associated with prejudiced attitudes when controlling for the effects of the key constructs from the other frameworks. Finally, both outgroup (β = − 0.388; p < 0.001) and ingroup (β = 0.073; p < 0.001) empathy were associated with prejudice. As expected, outgroup empathy was strongly and negatively associated with prejudice, while ingroup empathy weakly predicted prejudicial attitudes.

Model 2: Predicting Bias-Motivated Aggression

In the BMA analysis, sex was positive and significant across all models (see Table 2). Model 1 shows the effect of contact. Findings show that a one standard deviation increase in contact quality decreased the frequency of BMA (IRR = 0.667, p < 0.001), while contact frequency was not significantly related to BMA (Hypothesis 1 partially supported). Similarly to the prejudice model above, these results demonstrate that it is contact quality, rather than frequency, which is related to BMA. Model 2 shows the results of the dual-process model. Findings show that a one standard deviation increase in RWA (IRR = 1.125, p < 0.01) and SDO (IRR = 1.360, p < 0.001) is related to more frequent self-reported BMA (Hypothesis 2 supported). These results further show that SDO mattered more for understanding participants’ self-reported BMA compared to RWA. Model 3 shows the effect of perceived injustice, which was small and positive (IRR = 1.140, p < 0.001; Hypothesis 3 supported). This finding suggests that participants who felt more aggrieved by perceived injustices reported more frequent engagement in BMA. The role of prejudice and exposure to peer outgroup hostility were jointly studied in Model 4. Findings demonstrate a strong net effect of prejudice (IRR = 1.483, p < 0.001), which suggests that participants who harbored more prejudiced views self-reported a higher frequency of BMA. There was a smaller positive association between participants’ reported exposure to peer outgroup hostility and BMA (IRR = 1.164, p < 0.001; Hypothesis 4 supported), which indicates that those with peer networks who held hostile views towards perceived outgroups more frequently engaged in BMA. Model 5 displays the results of empathy on BMA. Interestingly, outgroup empathy had a stronger effect than ingroup empathy. The effect of outgroup empathy was negative (IRR = 0.705, p < 0.001), thereby decreasing the frequency of self-reported BMA. Ingroup empathy had a very small positive effect (IRR = 1.097, p < 0.05), which suggests that those who were more empathic towards their ingroup self-reported BMA more frequently (Hypothesis 5 supported).

Finally, a model comprising all of the variables from the pre-existing theories of prejudice was run to examine the comparative effects of each item on BMA (Model 6). Findings showed a strong effect of prejudice (IRR = 1.193, p < 0.01) and exposure to peer outgroup hostility (IRR = 1.123, p < 0.01) on BMA, which suggests that those with more prejudiced views, and those who had contact with peers who held hostile views reported a higher frequency of BMA. Of the dual-process model, only SDO (IRR = 1.111, p < 0.05) was significantly associated with BMA, suggesting that one’s desire for power and hierarchical structure, rather than group cohesiveness, was a stronger correlate of engagement in BMA. Finally, of the contact measures, only contact quality (IRR = 0.802, p < 0.001) was associated with BMA, which indicates that those who have higher quality contacts with perceived outgroups engaged in BMA less frequently. In this comparative model, perceived injustice and empathy were not statistically associated with BMA.

Discussion

The objective of the present study was twofold. First, we sought to establish the relationship between intergroup contact (frequency and quality), negative worldviews from the dual-process model (i.e., RWA and SDO), perceived injustice, exposure to peer outgroup hostility, and ingroup and outgroup empathy. Second and more importantly, we aimed to compare competing theoretical frameworks to understand the key correlates of prejudice and BMA. In examining the results within the comparative models, a preliminary conclusion that can be drawn is that these theories vary in their ability to explain individual differences in prejudice and BMA.

Firstly, the contact hypothesis, one of the most well-regarded models of social psychology, performed well in both comparative models, but as expected, it was the quality of contact that was statistically significant, not the frequency of contact. This finding supports prior research, which demonstrates stronger and more positive effects of contact quality in reducing harmful outgroup attitudes (see, e.g., Johnston & Glasford, 2018). It makes intuitive sense that the quality of the contact an individual has with an outgroup member can positively shape their attitudes towards that individual and the group to which they belong. Resultantly, such types of contact may serve to eliminate the boundaries demarcating ingroups from outgroups and constitute one way to promote more inclusive and common social identities (Eller & Abrams, 2004). However, in addition to attitudinal dispositions, our findings also show that the quality of contact goes some way in assuaging behavioral intentions (i.e., BMA). Taken together, our results show that quality contact may be an important antecedent to reducing the likelihood for individuals to harbor prejudicial attitudes or engage in bias-motivated aggressive behaviors.

The dual-process model also performed well across both comparative models, but there was a stronger association of both RWA and SDO on prejudice, while only SDO had a weak effect when included in the comparative model measuring BMA. The former results align with a large body of research that consistently finds that both RWA and SDO are strong predictors of prejudice (see, e.g., Asbrock et al., 2010; Duckitt, 2006; Duckitt & Sibley, 2007, 2010). Moreover, as RWA and SDO are predominantly operationalized as statements of social attitudes rather than behavioral intentions (Sibley & Duckitt, 2008), the former results support this pre-existing research (see also Asbrock et al., 2010). However, we speculate that the latter results may suggest that RWA and SDO are indirectly associated with BMA through the mechanism of prejudice. It is important to note that both RWA and SDO have different motivational origins, with SDO concerned with establishing and maintaining hierarchical boundaries (Asbrock et al., 2010), while RWA is premised on enforcing ingroup norms (Duckitt & Sibley, 2007). Prior research suggests that individuals with high levels of SDO may be less inclined to engage in BMA if they perceive that immigrant groups are maintaining a subordinate status (Thomsen et al., 2008). As such, the level of perceived identity threat participants may have felt from immigrants, for example through the perception that immigrants are assimilating and therefore blurring boundaries, may explain the positive association between SDO and BMA in our model.

The perceived injustice model did not perform well in explaining prejudice and BMA. This does not mean that perceived injustice is unimportant, but its role is probably better understood as one of the indirect triggers of BMA (Moghaddam, 2005). This is in line with research on political violence, which suggests that perceived injustice indirectly shapes attitudes to violence (Doosje et al., 2013). In this sense, perceived injustice does not necessarily translate into bias-motivated aggressive behaviors.

A similar pattern is identifiable regarding the relationship between empathy and BMA, but not prejudice. Outgroup empathy was particularly relevant for predicting BMA, but there were no direct effects in the final model, which aligns with prior research showing that empathy is an important mediator of prejudice (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). However, both ingroup and outgroup empathy were associated with perceptions of prejudice. Specifically, outgroup empathy was negatively associated with prejudice, while ingroup empathy was positively associated with prejudice, which supports prior research regarding the relationship between empathy and prejudice (Gutsell & Inzlicht, 2012).

Finally, the effects of the socialization model differed in both analyses. There was no significant effect of exposure to peer outgroup hostility on participants’ perceptions of prejudice in the first comparative model, contrary to theoretical expectations. A large body of research speaks to the influence of socialization processes on prejudice, whereby learned norms, values, and beliefs from an anti-social individual or group can shape one’s prejudiced attitudes (Allport, 1954; Hjerm et al., 2018). Thus, our finding is perplexing. Yet as we tested a comparative model, this result suggests that when compared to other models of prejudice, socialization processes may not be as important when considered against other key antecedents of prejudice (e.g., RWA; SDO) and mechanisms to protect against prejudice (e.g., empathy). However, the effect of exposure to peer outgroup hostility remained significant in the comparative model predicting BMA, although the effect was rather small. As exposure to anti-social peers is an important and strong covariate for all kinds of deviance in self-reported offending studies, this effect deserves further attention.

Implications

Prejudice and BMA are endemic and enduring social problems affecting societies globally. Their prevalence can have harmful consequences, such as intergroup divisiveness, outgroup discrimination, poor mental and physical wellbeing, and increased fear and perceived threat (e.g., De Waele & Pauwels, 2014; Doosje et al., 2013; Williams et al., 2019), which are especially problematic in an increasingly globalized world. Hence, identifying ways to reduce the incidence and normalization of prejudicial attitudes and behaviors is critical. Policy is about making decisions in an uncertain world and drawing policy implications from a cross-sectional study is a hazardous enterprise. This does not mean that nothing can be said with policy relevance; our policy implications are thus based on what we found in the data.

Our data show that individuals differ in many ways, from levels of empathy to attitudinal tendencies such as RWA and SDO, outgroup contact, peer influences, and personal attitudes and norms. Given the partial overlap between the predictors of prejudice (attitudes) and BMA (behaviors), it is important to focus on measures that avoid the translation of perceived injustices and the so-called negative worldview variables (i.e., RWA and SDO) into prejudice and BMA. Learning to deal with negative worldviews is part of what crime prevention scholars call ‘moral education’ (Wikström & Treiber, 2017). The individuals (e.g., family members; peers) and institutions (e.g., educational settings; religious institutions) a person is exposed to heavily influences their socialization processes and the moral norms that guide their behavior (Wikström & Treiber, 2017). Divergent developmental experiences provide important information for understanding the extent to which individuals ascribe importance and adhere to such norms. Moreover, how much an individual’s moral norms align with formal rules and laws is indicative of their likelihood to be law-abiding. Thus, developing effective interventions that seek to develop or reinforce one’s moral education may promote prosocial attitudes and reduce the propensity to nurture prejudicial beliefs or behavioral intentions.

Relatedly, developing strategies to reduce intergroup biases by fostering empathy and creating a culture of tolerance may also go some way in ameliorating prejudicial attitudes and behaviors. Prior research shows that when individuals feel empathy towards outgroup members, they tend to harbor less prejudicial attitudes and are less inclined to engage in aggressive behaviors because they sympathize with the experiences of those groups (Miklikowska, 2018). As empathy is developed from an early age, identifying deficiencies in empathy, and ensuring interventions are in place to improve individual empathic abilities may reduce antisocial and criminogenic behaviors (Trivedi-Bateman & Crook, 2021). In a similar vein, creating a higher degree of tolerance in individuals may also serve to mitigate the effects of prejudicial attitudes and behaviors. Tolerance is important as it enables an individual to accept the values and beliefs of another without having to temper their own, even if such values and beliefs stand in contrast to theirs (Verkuyten et al., 2020). This is particularly crucial in contexts whereby prejudice and aggressive behaviors stem from negative attitudes towards perceived outgroups. Thus, it represents one of “the few viable solutions to the tensions and conflict brought about by multiculturalism and political heterogeneity” (Gibson, 2006, p. 21). Through a tolerance-building approach, the focus is on accepting different beliefs and ways of life that one may not approve of, rather than focusing on improving perceptions of the groups that nurture such beliefs and lifestyles (Verkuyten et al., 2020).

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the contribution of our findings for understanding the correlates of prejudice and BMA more holistically, there are some limitations that must be considered when interpreting the findings. Firstly, this study used a cross-sectional design, which means causal or temporal relationships between variables cannot be established. Panel studies are welcomed to gain insight into the long-term relationship between empathy and prejudice development, the direction of effects, and the relative effects of cognitive and affective aspects of empathy. Secondly, this study was conducted by drawing on a sample of Belgian participants; hence items measuring ingroup and outgroup processes were tailored specifically to understand perceptions of outgroups who are prominent minority groups in Belgium. While the findings herein are specific to this sample, they offer important insights for understanding prejudice and BMA more broadly. In other words, this study provides a foundation for future research to determine whether these relationships exist in differing contexts. Doing so will provide a solid steppingstone for developing an integrated model of prejudice and BMA.

Thirdly, this study used general measures of empathy towards the ingroup and outgroup. Drawing on other measures of empathy may elucidate differing cognitive, affective, and physiological mechanisms relevant to attitudinal and behavioral manifestations of bias (Neumann et al., 2015). Finally, while the aim of this study was to compare models containing variables from key perspectives, it draws from data that did not include certain constructs (e.g., the big five personality characteristics), which may further help to understand the antecedents of prejudice and BMA. Continuing to draw on theory comparison to learn more about how different theories can collectively explain prejudice and BMA is worthy of inquiry. Subsequent studies can utilize the findings herein to develop integrated theories. Examples in the literature are abundant in the field of political protest studies (e.g., Opp & Brandstätter, 2010). In addition, it may be fruitful to examine the explanatory role of mediators and moderators (e.g., empathy) within a comparative model to understand the differential influence of such factors on existing theories.

Conclusion

To conclude, this study provided a comparative theoretical examination of key theories to explain prejudice and BMA. Theory comparison has been heavily promoted by different scholars as it is an important part of an analytical approach to theory testing (Opp & Wippler, 1990). Moreover, empirically testing a comparative theoretical model to understand a particular social problem is critical to advancing knowledge of and ways to address it. The theory comparison conducted in the present study has highlighted the factors conducive to one’s greater likelihood of being prejudiced or engaging in BMA, as well as the factors that may alleviate such a propensity. Our study has also demonstrated the value of and need for theoretical integration in understanding one of the most persistent problems plaguing humanity: the ingroup-outgroup syndrome. The present study is restricted to understanding attitudes and behavioral intentions towards immigrants, but social exclusion and its associated consequences exist for other groups too (e.g., religious groups; LGBT + groups; discrimination based on sex, age). While we cannot extrapolate the findings of this study to these other groups, such ingroup/outgroup processes are critical to understand in varying contexts. As such, this study provides a solid basis for advancing our knowledge of how biased attitudinal and behavioral intentions can be fostered and alleviated more broadly.

Notes

An important and often overlooked restriction of using self-reported measures of past behavior is the lack of spatio-temporal convergence. For example, one may theoretically assume that peers play an important role in the causation of BMA, but it is impossible to test whether people’s behaviors are situationally induced by the mere presence of their peers at the moment of committing the act that one reports having committed. For a discussion on situational versus developmental effects and the way they are tested, see Wikström and Kroneberg (2022).

To be eligible to participate in the study, it was a requirement that participants and their parents were born in Belgium. This was done to enable an examination of ingroup and outgroup processes whereby the perceived outgroup was identified as Moroccan and Turkish immigrant students. Thus, scales such as the contact scale were adapted to ask participants about their contact with Moroccan and Turkish immigrant students as the perceived outgroup. The strength of this approach is that we gain insight into the correlates of Belgian students and their attitudes, norms, and behaviors towards specific outgroups. The downside is that we cannot compare the correlates of BMA within specific populations of Moroccan or Turkish participants (and their attitudes and behaviors towards Belgian participants). Some studies use very general questions/items to measure BMA, which may affect both content validity and correlational validity.

References

Abbott, N., & Cameron, L. (2014). What makes a young assertive bystander? The effect of intergroup contact, empathy, cultural openness, and in-group bias on assertive bystander intervention intentions. Journal of Social Issues, 70(1), 167–182.

Agnew, R. (2006). Pressured into crime: An overview of general strain theory. Oxford University Press.

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Perseus.

Altemeyer, R. A., & Altemeyer, B. (1981). Right-wing Authoritarianism. University of Manitoba Press.

Altemeyer, B. (1998). The other “authoritarian personality”. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 30, pp. 47–92). Elsevier.

Asbrock, F., Sibley, C. G., & Duckitt, J. (2010). Right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation and the dimensions of generalized prejudice: A longitudinal test. European Journal of Personality, 24(4), 324–340.

Barkin, S., Kreiter, S., & DuRant, R. H. (2001). Exposure to violence and intentions to engage in moralistic violence during early adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 24(6), 777–789.

Beelmann, A., & Heinemann, K. S. (2014). Preventing prejudice and improving intergroup attitudes: A meta-analysis of child and adolescent training programs. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35(1), 10–24.

Bruinsma, G. J. (1994). De test-hertest betrouwbaarheid van het meten van jeugdcriminaliteit. Tijdschrift Voor Criminologie, 36(3), 218–235.

Cikara, M., Bruneau, E. G., & Saxe, R. R. (2011). Us and them: Intergroup failures of empathy. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(3), 149–153.

Cohrs, J. C., & Stelzl, M. (2010). How ideological attitudes predict host society members’ attitudes toward immigrants: Exploring cross-national differences. Journal of Social Issues, 66(4), 673–694.

Craig, M. A., & Richeson, J. A. (2014). Not in my backyard! Authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, and support for strict immigration policies at home and abroad. Political Psychology, 35(3), 417–429.

Daskin, E. (2016). Justification of violence by terrorist organisations: Comparing ISIS and PKK. Journal of Intelligence and Terrorism Studies, 1, 1–14.

Davis, M. H. (1980). A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 10(85), 3–19.

De Dreu, C. K., & Kret, M. E. (2016). Oxytocin conditions intergroup relations through upregulated in-group empathy, cooperation, conformity, and defense. Biological Psychiatry, 79(3), 165–173.

De Waele, M. S., & Pauwels, L. (2014). Youth involvement in politically motivated violence: Why do social integration, perceived legitimacy, and perceived discrimination matter? International Journal of Conflict and Violence (IJCV), 8(1), 134–153.

Diekhof, E. K., Wittmer, S., & Reimers, L. (2014). Does competition really bring out the worst? Testosterone, social distance and inter-male competition shape parochial altruism in human males. PLoS ONE, 9(7), 1–11.

Doosje, B., Van den Bos, K., Loseman, A., Feddes, A. R., & Mann, L. (2012). “My in-group is superior!”: Susceptibility for radical right-wing attitudes and behaviors in dutch youth. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 5(3), 253–268.

Doosje, B., Loseman, A., & Van Den Bos, K. (2013). Determinants of radicalization of Islamic youth in the Netherlands: Personal uncertainty, perceived injustice, and perceived group threat. Journal of Social Issues, 69(3), 586–604.

Duckitt, J. (2006). Differential effects of right wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation on outgroup attitudes and their mediation by threat from and competitiveness to outgroups. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(5), 684–696.

Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. G. (2007). Right wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and the dimensions of generalized prejudice. European Journal of Personality: Published for the European Association of Personality Psychology, 21(2), 113–130.

Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. G. (2010). Personality, ideology, prejudice, and politics: A dual process motivational model. Journal of Personality, 78(6), 1861–1894.

Durrheim, K., Quayle, M., & Dixon, J. (2016). The struggle for the nature of “prejudice”:“Prejudice” expression as identity performance. Political Psychology, 37(1), 17–35.

Eller, A., & Abrams, D. (2004). Come together: Longitudinal comparisons of Pettigrew’s reformulated intergroup contact model and the common ingroup identity model in Anglo-French and Mexican-American contexts. European Journal of Social Psychology, 34(3), 229–256.

Esses, V. M., & Hodson, G. (2006). The role of lay perceptions of ethnic prejudice in the maintenance and perpetuation of ethnic bias. Journal of Social Issues, 62(3), 453–468.

Faragó, L., Kende, A., & Krekó, P. (2019). Justification of intergroup violence–the role of right-wing authoritarianism and propensity for radical action. Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict, 12(2), 113–128.

Finlay, K. A., & Stephan, W. G. (2000). Improving intergroup relations: The effects of empathy on racial attitudes 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(8), 1720–1737.

Gibson, J. L. (2006). Enigmas of intolerance: Fifty years after Stouffer’s communism, conformity, and civil liberties. Perspectives on Politics, 4(1), 21–34.

Goodwin, K. A., & Goodwin, C. J. (2016). Research in psychology: Methods and design. John Wiley & Sons.

Gutsell, J. N., & Inzlicht, M. (2012). Intergroup differences in the sharing of emotive states: Neural evidence of an empathy gap. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7(5), 596–603.

Gwon, S. H., & Jeong, S. (2018). Concept analysis of impressionability among adolescents and young adults. Nursing Open, 5(4), 601–610.

Heylen, B. (2015). The dark side of human sociality: the evolutionary roots of contemporary prejudice and bias motivated behaviors. [Doctoral Dissertation]. Belgium.

Hjerm, M., Eger, M. A., & Danell, R. (2018). Peer attitudes and the development of prejudice in adolescence. Socius, 4(1), 1–11.

Hoeben, E. M., Osgood, D. W., Siennick, S. E., & Weerman, F. M. (2021). Hanging out with the wrong crowd? The role of unstructured socializing in adolescents’ specialization in delinquency and substance use. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 37(1), 141–177.

Holmberg, L., & Kyvsgaard, B. (2003). Are immigrants and their descendants discriminated against in the Danish criminal justice system? Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, 4(2), 125–142.

Johnston, B. M., & Glasford, D. E. (2018). Intergroup contact and helping: How quality contact and empathy shape outgroup helping. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 21(8), 1185–1201.

Kenworthy, J. B., Turner, R. N., Hewstone, M., & Voci, A. (2005). Intergroup contact: When does it work, and why. In J. F. Dovidio, P. Glick, & L. A. Rudman (Eds.), On the Nature of Prejudice: Fifty Years After Allport (pp. 278–292). Blackwell Publishing.

Long, J. S., & Ervin, L. H. (2000). Using heteroscedasticity consistent standard errors in the linear regression model. The American Statistician, 54(3), 217–224.

Lösel, F., King, S., Bender, D., & Jugl, I. (2018). Protective factors against extremism and violent radicalization: A systematic review of research. International Journal of Developmental Science, 12(1–2), 89–102.

Matthews, M., Levin, S., & Sidanius, J. (2009). A longitudinal test of the model of political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Political Psychology, 30(6), 921–936.

Menard, S., Bowman-Bowen, L. C., & Lu, Y. (2016). Self-reported crime and delinquency. In B. Huebner & T. Bynum (Eds.), The Handbook of Measurement Issues in Criminology and Criminal Justice (pp. 475–495). New Jersey: Wiley Blackwell.

Miklikowska, M. (2018). Empathy trumps prejudice: The longitudinal relation between empathy and anti-immigrant attitudes in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 54(4), 703–717.

Miller, P. A., & Eisenberg, N. (1988). The relation of empathy to aggressive and externalizing/antisocial behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 324–344.

Moghaddam, F. M. (2005). The staircase to terrorism: A psychological exploration. American Psychologist, 60(2), 161–169.

Neumann, D. L., Chan, R. C., Boyle, G. J., Wang, Y., & Westbury, H. R. (2015). Measures of empathy: Self-report, behavioral, and neuroscientific approaches. In G. J. Boyle, D. H. Saklofske, & G. Matthews (Eds.), Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Constructs (pp. 257–289). Academic Press.

Nezlek, J. B., Feist, G. J., Wilson, F. C., & Plesko, R. M. (2001). Day-to-day variability in empathy as a function of daily events and mood. Journal of Research in Personality, 35(4), 401–423.

Opp, K.-D., & Brandstätter, H. (2010). Political protest and personality traits a neglected link. Mobilization An International Quarterly, 15(3), 323–346.

Opp, K.-D., & Wippler, R. (1990). Resümee: Probleme und Ertrag eines empirischen Theorienvergleichs. In K.-D. Opp & R. Wippler (Eds.), Empirischer Theorienvergleich (pp. 229–233). Springer.

Paluck, E. L., Green, S. A., & Green, D. P. (2019). The contact hypothesis re-evaluated. Behavioural Public Policy, 3(2), 129–158.

Pauwels, L., & Schils, N. (2016). Differential online exposure to extremist content and political violence: Testing the relative strength of social learning and competing perspectives. Terrorism and Political Violence, 28(1), 1–29.

Pauwels, L. J., Ljujic, V., & De Buck, A. (2020). Individual differences in political aggression: The role of social integration, perceived grievances and low self-control. European Journal of Criminology, 17(5), 603–627.

Pauwels, L. J. R., & Heylen, B. (2020). Perceived group threat, perceived injustice, and self-reported right-wing violence: An integrative approach to the explanation right-wing violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(21–22), 4276–4302.

Peterson, R. A., & Merunka, D. R. (2014). Convenience samples of college students and research reproducibility. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 1035–1041.

Pettigrew, T. F. (1997). Generalized intergroup contact effects on prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(2), 173–185.

Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology, 49(1), 65–85.

Pettigrew, T. F., & Meertens, R. W. (1995). Subtle and blatant prejudice in Western Europe. European Journal of Social Psychology, 25(1), 57–75.

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(5), 751–783.

Pettigrew, T. F., Tropp, L. R., Wagner, U., & Christ, O. (2011). Recent advances in intergroup contact theory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(3), 271–280.

Piquero, A. R., Macintosh, R., & Hickman, M. (2002). The validity of a self-reported delinquency scale: Comparisons across gender, age, race, and place of residence. Sociological Methods & Research, 30(4), 492–529.

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., & Levin, S. (2006). Social dominance theory and the dynamics of intergroup relations: Taking stock and looking forward. European Review of Social Psychology, 17(1), 271–320.

Schmid, K., Hewstone, M., Küpper, B., Zick, A., & Tausch, N. (2014). Reducing aggressive intergroup action tendencies: Effects of intergroup contact via perceived intergroup threat. Aggressive Behavior, 40(3), 250–262.

Schröder, C. P., Bruns, J., Lehmann, L., Goede, L.-R., Bliesener, T., & Tomczyk, S. (2022). Radicalization in Adolescence: The Identification of Vulnerable Groups. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 28(1), 1–25.

Sibley, C. G., & Duckitt, J. (2008). Personality and prejudice: A meta-analysis and theoretical review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12(3), 248–279.

Sibley, C. G., Duckitt, J., Bergh, R., Osborne, D., Perry, R., Asbrock, F., Robertson, A., Armstrong, G., Wilson, M. S., & Barlow, F. K. (2013). A dual process model of attitudes towards immigration: Person × residential area effects in a national sample. Political Psychology, 34(4), 553–572.

Sidanius, J., Kteily, N., Sheehy-Skeffington, J., Ho, A. K., Sibley, C., & Duriez, B. (2013). You’re inferior and not worth our concern: The interface between empathy and social dominance orientation. Journal of Personality, 81(3), 313–323.

Stephan, W. G., & Finlay, K. (1999). The role of empathy in improving intergroup relations. Journal of Social Issues, 55(4), 729–743.

Thomsen, L., Green, E. G., & Sidanius, J. (2008). We will hunt them down: How social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism fuel ethnic persecution of immigrants in fundamentally different ways. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(6), 1455–1464.

Trivedi-Bateman, N., & Crook, E. L. (2022). The optimal application of empathy interventions to reduce antisocial behaviour and crime: A review of the literature. Psychology, Crime & Law, 28(8), 1–24.

Tyler, T. R., & Trinkner, R. (2017). Why children follow rules: Legal socialization and the development of legitimacy. Oxford University Press.

Vachon, D. D., Lynam, D. R., & Johnson, J. A. (2014). The (non) relation between empathy and aggression: Surprising results from a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 140(3), 751–774.

Van der Heijden, P. G., Sijtsma, K., & t Hart, H. (1995). Self-report delinquentie-schalen zijn nog steeds betrouwbaar. Een reactie op de studies van Bruinsma. Tijdschrift Voor Criminologie, 37(1), 71–77.

Van Hiel, A., & De Clercq, B. (2009). Authoritarianism is good for you: Right-wing authoritarianism as a buffering factor for mental distress. European Journal of Personality, 23(1), 33–50.

Verkuyten, M., Yogeeswaran, K., & Adelman, L. (2020). Toleration and prejudice-reduction: Two ways of improving intergroup relations. European Journal of Social Psychology, 50(2), 239–255.

Wikström, P. O. H., & Kroneberg, C. (2022). Analytic criminology: Mechanisms and methods in the explanation of crime and its causes. Annual Review of Criminology, 5(1), 179–203.

Wikström, P. O. H., & Treiber, K. (2017). Beyond risk factors: An analytical approach to crime prevention. In B. Teasdale & M. S. Bradley (Eds.), Preventing Crime and Violence (pp. 73–87). Springer.

Williams, D. R., Lawrence, J. A., Davis, B. A., & Vu, C. (2019). Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health Services Research, 54(1), 1374–1388.

Williamson, H., De Buck, A., & Pauwels, L. J. (2021). Perceived injustice, perceived group threat and self-reported right-wing violence: An integrated approach. Monatsschrift Für Kriminologie Und Strafrechtsreform, 104(3), 203–216.

Wolfowicz, M., Litmanovitz, Y., Weisburd, D., & Hasisi, B. (2020). A field-wide systematic review and meta-analysis of putative risk and protective factors for radicalization outcomes. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 36(3), 407–447.

Zhou, S., Page-Gould, E., Aron, A., Moyer, A., & Hewstone, M. (2019). The extended contact hypothesis: A meta-analysis on 20 years of research. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 23(2), 132–160.

Acknowledgements

Lieven J.R. Pauwels thanks his former PhD student at Ghent University, Dr. Ben Heylen, for having added a number of scales to his questionnaire which led to this article.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Dr Ben Heylen and Professor Lieven Pauwels. Data analysis was performed by Professor Lieven Pauwels. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Professor Lieven Pauwels and Dr Harley Williamson and both authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

Table 3

Appendix 2 Factor Loadings

Intergroup contact frequency

Factor 1 | |

|---|---|

How often do you have contact with immigrants? | 0.961 |

How often do you have a conversation with immigrants? | 0.859 |

How often do you have contact with immigrants in the area where you live? | 0.565 |

Intergroup contact quality

Factor 1 | |

|---|---|

To what extent do you experience contact with immigrants as pleasant? | 0.864 |

To what extent do you experience contact with immigrants as annoying? Reversed item | 0.816 |

To what extent do you experience contact with immigrants as friendly? | 0.721 |

To what extent do you experience contact with immigrants as hostile? Reversed item | 0.718 |

RWA

Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

When someone breaks the rules, a good, severe punishment is the best way to teach him/her to distinguish the right from the wrong | 0.706 | 0.004 | -0.020 |

Kindness encourages loafers and criminals to take advantage of our weakness. It is therefore better to deal with such people with a firm and determined hand | 0.683 | -0.017 | -0.039 |

Sexual offenses such as rape and assault deserve more than just jail time; criminals who are guilty of this should also be given corporal punishment in public | 0.648 | -0.102 | -0.218 |

In these troubled times, laws must be enforced without pity, especially when dealing with rioters and revolutionaries campaigning | 0.473 | 0.055 | 0.233 |

Our national heritage and customs have made us great, and some people should be encouraged to show more respect | 0.271 | 0.171 | 0.147 |

You can only live in this complicated world if you rely on experts and specialists | -0.169 | 0.764 | -0.010 |

Good leaders who respect and support the people must be strict, strict, and demanding | 0.258 | 0.520 | -0.068 |

During elections it is allowed to question and doubt, but when someone is elected and becomes the leader of our country, we owe him support and loyalty | 0.021 | 0.227 | 0.206 |

Young people sometimes get rebellious ideas, but as they get older, they should outgrow them | -0.032 | -0.061 | 0.705 |

Obedience and respect for authority are the most important virtues children should learn | 0.257 | -0.034 | 0.407 |

Many of our rules about modesty and sexual behavior are just habits that are no better or more sacred than rules that other people follow | -0.061 | 0.016 | 0.296 |

SDO

Factor | ||

|---|---|---|

1 | 2 | |

Equality of all social groups should be our ideal | 0.863 | -0.012 |

We should do everything possible to level the bar for the different groups | 0.828 | -0.027 |

I am in favor of increased social equality | 0.813 | 0.002 |

It would be good if all groups were equal | 0.766 | 0.047 |

We would have fewer problems if we treated all people more equally | 0.724 | 0.037 |

Members of all groups should have an equal chance in life | 0.630 | 0.099 |

No group should be allowed to dominate our society | 0.566 | 0.025 |

We should strive to make incomes as equal as possible | 0.555 | -0.038 |

Inferior groups should stay in place | -0.044 | 0.845 |

Sometimes certain groups have to be kept in place | -0.112 | 0.844 |

If some groups stayed in place, we would have fewer problems | 0.036 | 0.693 |

It's probably a good thing that some groups are at the top of the ladder and others are at the bottom | 0.139 | 0.656 |

Some groups of people are simply inferior to other groups | 0.108 | 0.604 |

To get ahead in life it is sometimes necessary to cut off other groups | 0.079 | 0.603 |

To get what you want, it is sometimes necessary to use violence against members of other groups | -0.039 | 0.484 |

It is only natural that members of some groups have more opportunities in life than others | 0.251 | 0.433 |

Perceived personal injustice

Factor 1 | |

|---|---|

It makes me angry when I think about how I am treated compared to others in Belgium | 0.618 |

I think I'm less fortunate than others in Belgium | 0.729 |

I feel like I am being discriminated against | 0.829 |

When I compare myself to others in Belgium, I feel that I am being treated unfairly | 0.895 |

Perceived group injustice

Factor 1 | |

|---|---|

I think the group I belong to is less fortunate than other groups in Belgium | 0.763 |

It makes me angry when I think about how the group, I belong to is treated compared to other groups in Belgium | 0.769 |

When I compare the group, I belong to with other groups in Belgium, I have the idea that we are being treated unfairly | 0.874 |

I think the group I belong to is being discriminated against | 0.902 |

Exposure to peer outgroup hostility

Factor 1 | |

|---|---|

Stolen something from an immigrant | 0.809 |

A male or female immigrant is sexually harassed (e.g., by making sexually suggestive comments, making sexual touches without her/he wishing it, trying to force sex….) | 0.780 |

Property of immigrants smeared, damaged, or destroyed (e.g., graffiti on a wall, knocking over a garbage bag, setting fire to a letterbox…) | 0.770 |

One or more immigrants intimidated alone or with friends | 0.764 |

Dealing aggressively with immigrants (e.g., fighting, throwing something at it…) | 0.715 |

Made it clear that they shouldn't have immigrants by explicitly saying this to them (e.g., by wearing a symbol, by drawing a saying on a wall, by adopting a certain style of clothing…) | 0.666 |

Immigrants not invited to participate in certain activities (e.g., going to a cafe, group work, etc.) | 0.583 |

Made it clear that they should not have immigrants without explicitly saying this to themselves (e.g., by calling them names, by raising certain gestures such as a middle finger…) | 0.544 |

Avoided immigrants (e.g., sitting in a different place on the bus, walking on the other side of the street, avoiding places where immigrants often come… | 0.314 |

Had negative feelings towards immigrants (e.g., fear, aversion, anger) | 0.272 |

Feeling uncomfortable when immigrants are around | 0.239 |

Outgroup empathy

Factor 1 | |

|---|---|

I often have tender, concerned feelings for immigrants who are less happy than I am | 0.651 |

I usually don't feel sorry for immigrants when they have problems | 0.414 |

When I see that immigrants are being taken advantage of, I feel quite protective of them | 0.574 |

The misfortune of immigrants usually doesn't affect me much | 0.638 |

When I see that immigrants are treated unfairly, I sometimes feel little pity for them | 0.482 |

I am often quite touched by the things I see happening to immigrants | 0.715 |

I would describe myself as a pretty tender-hearted person when it comes to immigrants | 0.704 |

Ingroup empathy

Factor 1 | |

|---|---|

I often feel concerned about Flemish people who are less happy than I am | 0.780 |

Sometimes I don't feel much pity for other Flemish people when they have problems | 0.585 |

When I see a Fleming being taken advantage of, I feel quite protective of them | 0.714 |

The accidents of other Flemish people usually don't disturb me much (reversed item) | 0.764 |

When I see that a Fleming is treated unfairly, I sometimes feel little pity for them | 0.478 |

I am often quite touched by the things I see happening to other Flemish people | 0.740 |

I would describe myself as a pretty tender-hearted person when it comes to Flemish people | 0.746 |

Prejudice

Factor 1 | |

|---|---|

I feel sympathy for immigrants (reversed item) | 0.759 |

I sympathize with the immigrant community (reversed item) | 0.729 |

Immigrants are just as honest as natives | 0.713 |

In general, I have a good feeling about immigrants (reversed item) | 0.711 |

Immigrants should have the sense not to impose themselves in places where they are not welcome | 0.708 |

Most immigrants could live perfectly without government support if they tried a little bit | 0.703 |

Some immigrants simply don't do their best to adapt. If they really wanted this, they would be just as well off as the Belgians | 0.638 |

I admire the immigrant community that lives here in harsh conditions (reversed item) | 0.626 |

Most politicians in Belgium care more about immigrants than about natives | 0.607 |

In the past it appeared that Italian immigrants adapted quickly to our culture. Turks and Moroccans should also do this, without being specially rewarded for this | 0.604 |

Immigrants and natives will never really get along, even if they are sometimes friends | 0.569 |

Immigrants have jobs that actually belong to natives | 0.560 |

The fact that immigrants descend from less well-off races explains why they are generally less well-off | 0.426 |

Immigrants teach their children values and skills that limit their chances of success in our society | 0.396 |

BMA

As the bias motivated aggression scale is a behavioral scale, no factor analysis has been conducted (see Bruinsma, 1994 and Van der Heijden et al., 1995 for a discussion of this issue). This variable measures the frequency of behavior. As behavior is affected by circumstances, we cannot expect the principles applied to attitudinal scales to be applied to behavioral scales. An alternative is the use of variety scales (see for example the discussion in Piquero et al., 2002).

Question Wording of BMA Scale

This behavioral scale probes if the participant ever had engaged in the behavior.

-

1. Have you ever done or experienced any of the following against an immigrant because of the fact that he or she is an immigrant? No/Yes’.

-

2. If yes: How often has this happened in the last 12 months? 0 times 1 time 2 times 3–5 times 6–10 times More than 10 times.

This allows for the creation of both a variety scale and a frequency scale. The items are:

-

Felt uncomfortable when there are immigrants in the area’

-

Had negative feelings towards immigrants (e.g., fear, aversion, anger, …)

-

Avoided immigrants (e.g., sitting in a different place on the bus, walking on the other side of the street, avoiding places where immigrants often come…)

-

Made it clear that I should not have immigrants without explicitly telling them this (e.g., by wearing a symbol, by drawing a saying on a wall, by adopting a certain style of clothing…)

-

Made it clear that I should not say this to immigrants explicitly (e.g., by calling them names, by raising certain gestures such as a middle finger…)

-

Immigrants not invited to participate in certain activities (e.g., going to a cafe, group work, etc.)

-

Intimidated one or more immigrants alone or with friends (e.g., threatening them in a group, chasing them, …)

-

Property of immigrants smeared, damaged, or destroyed (e.g., graffiti on a wall, knocking over a garbage bag, setting fire to a letterbox…)

-

Something stolen from an immigrant

-

Dealing aggressively with immigrants (e.g., fighting, throwing something at it…)

-