Abstract

Criminal policy processes often appear abstract and illusive, but sometimes a single criminal incident causes traceable policy impact. This article is about such an incident. A victim of a grave, violent assault published an opinion piece in a national newspaper, which sparked considerable public debate and policy actions. Some policy actions were new, and others had previously been proposed but repeatedly discarded. Based on an empirical study of the victim’s opinion piece, the ensuing media debate, and subsequent policy actions, we explore why and how certain victim’s stories capture their audience and strike a responsive chord in the public and in politicians. In the article, we analyze how the victim presents the incident as a narrative, and we identify the central features of the media debate and trace its visible impact on victim policies and legislation. We explore how some elements of the story are silenced in the political aftermath and how other elements serve as capital for politicians in pursuing their own agendas. A closer look at the policy changes in the wake of this opinion piece reveals that the story legitimizes certain political decisions and ignores victims’ desire for structural changes. Our study adds to research of “political agenda setting” by investigating the narrative power of an individual case on policy-making and by exhibiting the complex interplay between an individual story, media attention, and policy-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

He mutilated my body and face with a heavy water pipe. Then he threw my unconscious body out of the window from the third floor. It happened three years ago. I was well engaged in a career in the fashion industry. I was active and happy about my life. That life only exists as loss and memories now. (Duus 2012)Footnote 1

This is the introduction of an opinion pieceFootnote 2 that appeared in the national Danish newspaper, Politiken, in February 2012. The victim argued that the state prioritizes offenders over victims in helping offenders, rather than victims of crime. At the time of the opinion piece, her assailant was on parole and had been offered an internship with a celebrity chef as part of a rehabilitation program, while she as a victim felt she received very little and inadequate assistance. The author, Marlene Duus, became well-known, and her story and the matter she raised with her opinion piece were referred to as the “Marlene case” in the ensuing public and political debate.

The piece was read by 80,000 readers within 24 hFootnote 3 and triggered strong reactions from the politicians, stakeholder organizations, other victims, and citizens in general. A public debate followed, and legislative initiatives to help victims were enacted in parliament. As such, the opinion piece and its aftermath provide a unique opportunity for exploring the often hidden forces shaping public policy. This article is the result of a case study where we explore the impact of the opinion piece on criminal policy, examine how it came about, and provide a critical analysis of whether the political changes met the needs expressed in the opinion piece. We limit our study to criminal policy efforts directed at mitigating the effects of crime for victims. Hence, we do not explore the influence on penal policies.

The article begins with a review of existing research focusing on what has been termed “the rise of the high profile individual victim” as well as “political agenda setting.” We go on to present our analytical framework and data followed by an analysis in three parts: An analysis of central narrative elements in the opinion piece, an analysis of the media coverage of the case, and an analysis of how the narrative and the media coverage was translated into victim policies.

The Rise of the High Profile Individual Victim

Existing research suggests that a large part of the gains to victims’ rights over the last decades is of a symbolic nature (Elias 1986; Walklate 2012). Victims have moved from being the forgotten parts in the criminal justice process to being seen as “consumers of services” (Goodey 2004; Rock 2004). The term consumers is closely linked to the development of a market ideology that has coined not only victims but also citizens more broadly as consumers of public services since the 1990s. Consumerism emphasizes the need to quantify performance, to secure better quality of services, and to offer information. Victims have thus become units of measurement, service recipients, and supposedly more informed of their rights and possible services (Rock 2004: 213). It would be quite difficult for politicians nowadays to propagate criminal policies without addressing the victims as consumers of these policies (Walklate 2012). We therefore frequently see politicians consulting victim’s organizations and in their statements referring to individual cases present in the media scape (Goodey 2004: 22), as a mode of placing themselves as providers of services and making it known that they do so. As Walklate et al. (2019) note, individual cases have become particularly important drivers in policy debates and lawmaking. They refer to a growing number of legislation in different jurisdictions named after particular individual victims: Megan’s Law in the USA, 1994; Sarah’s Law in the UK, 2011; Byron’s Law in New South Wales, 2005; and Clare’s Law in the UK, 2014.

All these pieces of legislation derive from highly emotive and/or violent crimes (sex offences and homicide) and were largely implemented in response to the individual case after whom they are named, rather than from any substantive review or inquiry process. (ibid: 202)

The influence and presence of victims’ voices in policy debates have changed shape and form from being represented by victim centered organizations to “the rise of the high profile individual victim,” as Walklate et al. 2019 (ibid: 199) state. Though victims’ voices—at least when it comes to victim organizations or groups proclaiming to speak for victims—have played a less discernible role in Nordic countries than in North America and the UK (ibid: 200), our case study indicates that a similar tendency towards high profile individual victims as drivers in criminal policy might be emerging in the Nordic countries as well.

Our study is similar to a study on an Australian victim, Rosie Batty (Walklate et al. 2019). Both studies are case studies exploring an influential victim’s story by analyzing various publicly available sources referring to the victim, including media and parliamentary documents. Furthermore, both studies draw on narrative victimology. We do, however, employ a different analytical framework; the so-called narrative policy framework (NPF), and we combine the narrative victimology with main points from political agenda setting research, as they add to the understanding of the interplay between media stories and political action as well as placing our findings in a wider academic context.

How to Set the Political Agenda

The research field of “mediatization” has explored the interplay between media and political processes and has developed in the last decade to become more and more important in understanding how politics and legislation are created (Walgrave et al. 2017; Hepp et al. 2015; Strömbäck and Van Aelst 2013; Walgrave and Van Aelst 2006). There is “a remarkable dearth of systematic empirical research on the mediatization of politics” (Strömbäck 2011: 423), which some have claimed could be a result of difficulties connected to translating mediatization into operational and concrete research tools and hypotheses, and further that the field has a complexity which makes it difficult to measure by traditional empirical research (Schulz 2004 in Van Aelst et al. 2014: 201).

Within the scope of our study, we prefer the term “political agenda setting,” as scholars have used this term when paying special attention to the transfer of media priorities to actual political priorities (Van Aelst et al. 2014). Political attention is a precondition for political action, and lawmaking is a matter of information processing by political elites and institutions (Jones and Baumgartner 2005 in Walgrave et al. 2017: 548). In this process, some issues are ignored, while others are adopted. Previous research has explored what criteria have to be met in order for an issue to become agenda setting (e.g., Walgrave et al. 2017). The key elements seem to be that the issue has to address an important matter, it must present it in a negative coverage, it must point out an area of domestic policy that calls for problem solving, and it must clearly address a political actor with responsibility and agency to act (Walgrave and Van Aelst 2006). As we shall see, these elements are fulfilled in Marlene’s case, yet additional elements are worth noticing in order to explore what we could call the “narrative power” of an agenda setting issue.

Analyzing a Policy Narrative

When we consider the narrative power of Marlene’s story, we should attend to both the structural position and attributes of the victim as a storyteller and the various qualities of the story at play. Here, we think of the drama behind the incident, the emotions and “characters” at play, the rhetoric used, and the moral of the story. In correspondence with narrative victimology (Pemberton et al. 2019), we will explore the constitutive role of narratives, here primarily in the construction of a victim experience and how it is molded into victim policy and legislation.

Our analytical approach is inspired by sociological and political science theories on policy processes. Shore and Wright (1997) argue that policies are “cultural texts” and powerful tools for analyzing processes of governance. Policy may be expressed through rhetoric, narratives, written documents, institutional settings, and bureaucratic actors. However, Shore and Wright do not flesh out the specific features of narrative within their policy framework since their concern is broader. In order to grasp the cultural context of victim representations within these policy processes (Bacchi 2009), we are inspired by NPF’s approach (Jones et al. 2014)—a policy process framework that specifically addresses the importance of narratives in public policy. Jones et al. (ibid.) distinguish between three analytical levels in relation to policy narratives: a micro, a meso, and a macro level. The micro level explains how individuals are influenced by narratives, while the meso level deals with the ways in which different, competing groups use narratives strategically to affect policy development (ibid.). At this level, the authors propose that one should study the many actors involved in constructing and circulating policy narratives, such as the media, politicians, interest groups, and high profile citizens. The macro level targets “macro political institutions” such as parliaments, governments, and courts (Peterson 2018). It has been argued that the macro level in NPF theory is underdeveloped (Shanahan et al. 2018; Peterson 2018), but attempts have been made to combine the NPF meso level approach with another theory, PET (punctuated equilibrium theory). This latter theory shows how macro political institutions may interfere at the meso level if their “attention” is drawn to competing policy ideas at the meso level, for instance, prompted by “focusing events” or “internal debates” (Jones and Baumgartner 2005; Peterson 2018). These events or debates may serve to attract the attention of, for instance, governments and put the issue on their agenda, eventually leading to policy change (Peterson 2018). We believe that this combined approach of NPF and PET is valuable for our analysis since it may explain why and how ongoing policy discussions between, e.g., interest groups at a certain point become the target of political interference at the highest level.

Additionally, NPF argues that narrative truths are socially constructed and can be studied empirically and systematically. The approach provides us with useful tools for analyzing both the form and the content of a policy narrative. The form is defined by the structure of the narrative and its plot as well as its characters such as villains, victims, and heroes (Jones 2010). The narrative form further includes a moral of the story, which should be understood as the purpose that it gives to the involved actors’ proposals (Stone 2002). The moral of the story is therefore often portrayed as the ethical aspect of the proposed policy solution (Jones et al. 2014). While the NPF approach argues that the form of policy narratives is generalizable across sociocultural contexts, the content is relative to the specific context of the particular stories told (Jones et al. 2014: 5–7). Narrative content thus deals with the meanings and belief systems imbued in stories, as well as how these may be mobilized strategically by policy actors (ibid.). These two different elements of policy narratives may therefore also have methodological implications.

Although the methodological starting point of the NPF was characterized by a positivist, quantitative, and structuralist approach (Jones and McBeth 2010), researchers have subsequently developed qualitative approaches within the NPF framework (Gray and Jones 2016; Jones and Radaelli 2015). Even though we study through different policy levels (Shore and Wright 1997), the NPF meso level particularly resembles our analytical approach (Jones et al. 2014). describe the meso level methodology as doing content analysis of, for instance, media coverage, speeches, and written texts (Jones et al. 2014). Content analysis may be approached through both quantitative and qualitative methods. While a quantitative approach to content analysis aims to measure the degree to which audiences are exposed to issues, a qualitative approach analyzes the themes, meanings, and context of texts (Roller 2019). Furthermore, NPF holds that the form of narratives is quantifiable and amenable to the application of positivist tools of social science, whereas the content of these narratives is less transferable between narrative contexts and to a greater extent lend themselves to qualitative, context-aware analyses. Taking our point of departure in these analytical and methodological considerations, we combine our qualitative analysis of the meanings and beliefs expressed in the opinion piece and the following debate with a quantitative approach to the exposure of Marlene’s opinion piece.

Our Data

Our point of departure is the opinion piece authored by a 29-year-old woman who fell victim to an assault resulting in severe, permanent injury. It is a 2185 word piece which appeared in the largest national newspaper in Denmark, Politiken, on February 20, 2012. In addition to an analysis of the piece itself, we base our analysis on two types of documents: legal texts and written media coverage.

The legal texts were identified through an online search at the parliament’s website section on documents combined with a Google Search using keywords such as the name of the victim, victim initiatives, and victim legislation. The legal texts included travaux préparatoires, motions for government action, proposed legislation, adopted legislation, policy papers, policy action plans, and governmental reports. We focus our analysis on legal texts from February 2010 to 2014. The year 2010 was chosen as an analytical starting point because the task force on increased action vis-à-vis victims of crime appointed by the Minister of Justice issued a report that year (Ministry of Justice 2010). This task force constituted the first concerted effort on the part of the government to take stock of existing efforts to support victims of crime and considering new initiatives. By analyzing data from prior to the publication of the opinion piece, we are able to link later policy actions more accurately to its publication. We chose 2014 as an analytical end point, because the last legislative effort that we can directly link to Marlene’s opinion piece took place in November that year.

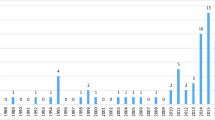

We identified the written media coverage through the digital media archive, Infomedia, using the author’s name as a search wordFootnote 4. Infomedia provides access to all written, published news in Denmark, including national newspapers, local newspapers, magazines, and webFootnote 5. Our search covered the period February 20, 2012 (the publication date) through 2014 following our ending point for legal texts. This resulted in 472 published news items (hits). We excluded notices as well as advertisements for Marlene’s opinion piece, commercials for TV debates, letters to the editor, except those coming from other victims, newspaper articles that repeated a main article already included in our corpus, and a few articles that could no longer be accessed. This left us with 111 written pieces for further analysis. The case was also covered in other types of media, but we decided against extending our search to those, as newspapers have a higher agenda setting impact than other media outlets (e.g., Bartels 1996 in Van Aelst et al. 2014: 205)Footnote 6. Moreover, we found that the newspaper articles adequately represented the various stakeholders and the political spectrum and reflected the different points of view raised in the debate.

Marlene’s Victim Narrative

In the following, we will unfold the narratives in the opinion piece carrying the title “Does the Victim get a Second Chance Too?”. In the piece, Marlene describes the assault she experienced from a former boyfriend in November 2008 and how it left her severely wounded (Duus 2012). She describes how she underwent surgery more than 20 times and how, at the time of the writing, she is unable to work and about to start rehabilitation in a brain injury facility. Her assailant was sentenced to 6 years in prison but was granted a leave after 2 years and was released on parole after three. Marlene was not notified about his release and describes how she was horrified to learn about this from a friend. As part of a rehabilitation program, the assailant got an internship with a celebrity chef and appeared in a television program while interning. Marlene’s key message in the opinion piece is that when it comes to getting help from the government in Denmark, offenders are first and victims second, and she argues that the order should be reversed.

Rhetorics, Emotions, and Plot

Marlene enforces her narrative with the use of a vivid language. She describes how she is thrown out of a window, how her teeth got smashed, how she is crouching on the floor, and how the offender is obsessed. Using this kind of framing evokes images in the reader, intensifying her message. In addition, she uses language with strong connotations. Words like “loss,” “lifeless,” “dead,” “mistreat,” and “smash” that carry strong negative associations are abundant in the opinion piece. She reinforces the built-in drama of her story by supplying the strong connotations with a sober, matter-of-fact narration using exact numbers like “I fell 11 meters,” “50 % disabled,” “29 years old,” and “6 years of prison.” The use of this logos works as an understatement and could be characterized as “inherent pathos,” meaning that implicitly communicated pathos is an especially strong tool that creates feelings in the recipient such as sympathy and anger (Beyer 2013). This use of logos and pathos conveys a subtle balance within the pathetic victim paradigm (Meyers 2016) as it on the one hand requires “claimants to have undergone severe, documentable, humanly inflicted harm” (ibid. p. 6) and on the other hand “you must in no way be complicit in your suffering to count as a victim” (ibid, p. 7). By listing the “facts,” Marlene makes it clear that she has been severely harmed while at the same time understating her suffering.

Character-driven narratives influence public opinion significantly more than narratives without characters (Crow and Berggren 2014), and NPF shows how powerful these characters can be. Translated into our analysis, Marlene positions her offender as the villain and herself as both the helpless victim and the “warrior” (hero), who stands up and fights for all victims. As we shall see later, some politicians try to establish themselves as heroes defending victims’ rights.

Marlene boosts her message of victims and evokes emotions of empathy and indignation in the reader by drawing on these characters, while, at the same time, she turns the classic plot upside down. In the classic plot, the protagonist progresses from helplessness to a situation of control (Stone 2002). Marlene reverses this order with her narrative of initially being in control with a subsequent retrogression due to the criminal event and its aftermath, which in turn leads to the helpless situation that she finds herself in at the time of writing. This is expressed through Marlene’s story about an active and happy life in an early-stage career, which is ruined by the assault. It is the story of a lost career, inactivity, and depression. Her account of inadequate help from the hospital, the police, the municipality, and the courts places these agencies in the role of alleged accomplices of her ruined life. She is involuntarily placed in a waiting position for monetary compensation for her injuries, she is let down and humiliated by the justice system, and she does not receive help to start a new professional life.

The offender, on the other hand, gets early release and rehabilitation and is not punished for breaking the rules of his parole. Thereby, the offender receives the benefits granted the hero in the classic plot: going from helplessness—incarceration—to a rehabilitation program and relationships with people of high social status (the celebrity chef) on to freedom. Positioning the offender as “free” (allowed to roam in the public sphere unsupervised), while Marlene is ‘bound’ because of injuries and the waiting position, makes the injustice clear:

I haven’t even finished my operations, before you let the offender resume his life. He is allowed to walk freely in the streets, before I even get diagnosed with posttraumatic stress. (Duus 2012 in Politiken)

This makes the reader conclude ahead of her: “The order is completely reversed!” Or as Marlene puts it: “1. Help the victim. 2. Help the offender.” (ibid). Changing the positions of the good and bad appeals to strong feelings of blatant injustice. As a member of parliament commented on Marlene’s case, “The evil are laughing, while the good guys are crying” (Flydtkjær 2012 in BT).

The strong dichotomy established by these characters adds to the emotional installment of the “victims first” message. The “victims first” message contains a zero-sum premise: There is a certain amount of help available, which is reduced when either the victims or the offenders are helped. As we shall see later, this zero-sum logic becomes cardinal in the media debate and is partly continued in the legislation process.

Victim’s Agency

In the case study by Walklate et al. (2019), the victim, Rosie Batty, is quoted, reflecting on why she and her story were heard. Rosie Batty connects her experience of getting a voice in the media with her privileged position:

I believe that one of the reasons I have been able to speak to so many people about my story, and why people are willing to listen, is because I am white, middle-class, well-educated and articulate. If I did belong to a rough neighborhood, or I were indigenous, or from other ethnic background or had a disability, I would not be heard. (Rosie Batty in Walklate et al. 2019: 207 Footnote 7)

As Walklate et al. (2019: 207) responds to her comment, these characteristics might very well encapsulate why Rosie Batty is heard—despite the widely documented difficulties being recognized as victims faced by women who have experienced violence at the hands of their partners or persons known to them. Marlene Duus is like Rosie Batty: “white, middle-class, well-educated, and articulate.” Rosie Batty has the ability to connect her story to a broader context of family violence and to create a sense of shared story. Similarly, Marlene expands her individual story to a general story (Jones et al. 2014) about Denmark as a state where the offenders are generally better treated than victims. McBeth et al. (2007) argue that when groups perceive themselves as a losing or weak party, they use narrative strategies to expand the issue and its potential relevance for a larger circle of supporters. In spite of the obvious differences between the cases and contexts of Rosie Batty and Marlene Duus, the variation in narrative content can be systematically studied through the narrative strategies and the belief systems addressed within these different narratives (Shanahan et al. 2018). In this case, the power of their stories is strengthened by drawing on an image of an ignorant, oppressive, instrumental system that neither understands what is at stake among the citizens nor is willing to make changes. “Some victims must speak up …”, Marlene states (Duus 2012), depicting herself as a victim who has the courage to speak up and do so on behalf of everyone, thereby becoming the (needed) voice of the people.

Stressing agency rather than victimhood, Marlene evokes the paradigm of the heroic victim (Walklate et al. 2019; Meyers 2016), deriving from the prisoner of conscience as the crown example (Meyers 2016: 7). Though Marlene Duus and Rosie Batty are not at risk of persecution for “speaking up,” they do freely choose to engage in public dissent and “goad the state’s repressive apparatus” (ibid: 8) for the sake of their beliefs based on their first-hand experiences. Moreover, they were both severely harmedFootnote 8. Simultaneously, Marlene draws on the pathetic victim paradigm (Meyers 2016) as the suffering, helpless, innocent victim, who has undergone severe harm (Meyers 2016: 6)Footnote 9, and this adds to the power of the heroic paradigm as the rise is “against all odds”:

I survive. A miracle, perhaps. But here my fight begins. Because nobody is going to take my life away. I’m a warrior, not a victim. These are words I tell myself when the fighting gets too tough. Reminding myself that I’m a warrior – against all odds. (Duus 2012)

Several of the elements mentioned here are similar to the dissemination of the story of Kathryn Steinle, who was shot by an undocumented immigrant in San Francisco in 2015. An NPF study by McBeth and Lybecker (2018) shows how the story of Kathryn Steinle played into the broader context of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. It did so by constructing sanctuary cities (cities with a large number of immigrants) as a public agenda setting problem narrated with Mexican immigrants as villains, the public as victim, and Trump as the hero (McBeth and Lybecker 2018: 869). Sharing a number of characteristics (female, white, middleclass, well-educated) and being severely injured through no fault of their own, Kathryn Steinle, Rosie Batty, and Marlene Duus were positioned as “damsels in distress.” This position attracts attention and places the politician taking action in the role of a hero.

Media as Joint Constructer of Victim Policy

The media provide important scenes for politicians to show participation and action (Walgrave and Van Aelst 2006). The opinion piece and the ensuing debate became a catalyst for parliamentary actions aimed at improving victims’ conditions. As all political parties were represented in the media debate (and several followed up with legislative initiatives), it seems that the opinion piece created what has been termed a “media storm” or “cascading” (Walgrave et al. 2017: 553), a sudden flood of media coverage where politicians want to outdo one another and be the first or among the first to adopt an obtrusive issue. Our analysis based on Infomedia shows that within the first 10 days after Marlene’s opinion piece, 17 politicians either authored a media post themselves or provided quotes for news articles on the issue. In this section, we will unfold the positions and character of voices in the media debate, as we will later see how this was followed up during law preparations.

Stakeholder Positions in the Media

When taking a closer look at who raised their voice, the broad appeal is clear: Various kinds of organizations working with specific interests for both victims and offenders expressed their views, politicians and well-known opinion leaders gave their say, experts explained how and why this could happen (e.g. early release), other victims and offenders told their personal stories, and ordinary citizens discussed Marlene’s story and message. Even the actors addressed in Marlene’s opinion piece defended themselves in the media: the chef and the offender. The debate also made Marlene give her say over and over again. Drawing on the NPF terminology (Jones et al. 2014), these competing stakeholder positions can be explained through a meso level analysis of the ways in which they used the Marlene narrative strategically to influence the political climate. Two main stakeholder positions were reflected in the media debate following Marlene’s piece: One that followed the position drawn by the opinion piece, echoing and strengthening the call for “victims first,” and one that in various ways challenged the opinion piece. The latter was mainly done by opposing the zero-sum logic, raising the importance of rehabilitation of offenders and pointing out that the specific case was unusual.

The stakeholders echoing Marlene’s “victim first” position were primarily victim organizations and other victims. The “victim first” position was also acquired by right-wing politicians and used in their well-known agendas of “tougher penalties” and “consequences of committing a crime.” Marlene’s dramatic description of the crime was quoted again and again, the number of her injuries and operations was repeated, the offender was positioned as “executioner,” and the idea of the Danish system being “too lenient” received a lot of support. Experts were positioned as people who “do not care about victims,” the chef was named as the “celebrity cook,” and the TV program with Marlene’s assailant was framed as a “fairy tale story.” We regard these arguments concerning offenders getting too much and victims getting too little as part of a broader criminal policy tendency towards penal populism (Garland 2001).

From the other main position, these attitudes were expounded as emotional and single case-oriented. As, e.g., the head of the Prison Association (Fængselsforbundet), Kim Østerbye, wrote in the newspaper Berlingske Tidende:

It is easy to be caught up by a personal story like that and allow emotions and the desire for revenge to overshadow our collective common sense … criminal policy should not be based on single cases. (Østerbye 2012)

Moreover, the position challenged the zero-sum premise by twisting the premise of victims first. Ole Wessel, project manager of High Five—an organization supporting inmates getting a job after their release—posed the question: “Should we refrain from helping him getting on with his life, because she is still in pain?” (Quoted in BT newspaper article by Lauritsen 2012). Similarly, the chef published an answer to Marlene in Politiken with the following words: “We are painfully aware that nothing of what we are doing can ease the victims’ grief” (Meyer 2012). This position was primarily voiced by offenders, left-wing politicians, and professionals working with resocialization of offenders or within prisons.

Political Action and Governmental Response

The first political action related to the opinion piece appeared 2 months after its publication. The Legal Affairs Committee of the Danish Parliament made a formal inquiry to the Minister of Justice, asking whether he would take steps to ensure that future victims of violent crime actually get the information they are entitled to about offenders’ leave or release from prison (Ministry of Justice 2012a). The fact that Marlene was not informed about her offender’s leave or release from prison is a key theme in the opinion piece. The minister did not answer the question explicitly, but in his reply to the committee, he accounted for the many steps taken already.

The next political action followed shortly after, in April and May 2012, where various opposition parties made two motions for government action (Motion B 76 2012; Motion B 90 2012). The first motion, proposed by a left wing opposition party, wanted the government to establish a victims’ fund to “increase awareness and knowledge of victims’ situation and strengthen the treatment and the support of victims of crime.” The second motion, sponsored by two right wing opposition parties, wanted the government to take legislative and administrative steps to increase the support for victims of violent crime. The second motion was rejected by parliament, while the first motion was negotiated with the government by the party behind it and incorporated into the policy action plan issued by the Minister of Justice of the Social Democratic dominated coalition government in June 2011. Under the heading “The government wants to help victims of crime” (Ministry of Justice 2012b), the government announced an action plan with three components:

-

1.

Establishing a victims’ fund with revenues from offenders. The purpose of the fund was to “(…) help victims of crime get on with their lives.” (Ibid)

-

2.

Informing victims beforehand, if the offender should be scheduled to appear as a central person in a TV program while serving time.

-

3.

Giving victims a more central role during trial by letting them testify before the examination of the offender. The Commission on the Administration of Criminal Justice was to draft a model for this.

The first component reflects Marlene’s point about not getting adequate support for getting “on with her life” (Duus 2012). Legislation was passed in May 2013 instituting a victims’ fund (Act no. 603, Victims’ Fund 2013). The victims’ fund was established with revenues from fines levied on certain Criminal Code and Road Traffic Act offenders (ibid) and was expanded from supporting victims of crime to including victims of traffic offenses as well. The fund, however, does not support individual victims. Instead, it is supposed to fund victims’ needs by, e.g., awarding grants for victim researchFootnote 10, counseling services for victims, and education for practitioners working with victims.

The second component is also closely linked to the opinion piece and was later turned into legislation that expanded the original scope from TV only to include radio programs and newspaper portrait interviews as well (Act no. 603, Victims’ Fund 2013; Act no. 1284 ( n.d.), Administration of Justice Act, section 741g.) According to the travaux préparatoires “… programs that follow a group of prisoners participating in special initiatives, including resocialization projects about cooking, choir singing, etc” (our italics) would be covered by the new statute (Bill no. 166 2013). This is a clear reference to the Marlene case, as her offender participated in a televised cooking project.

In addition to increased information for victims, parliament passed legislation aimed at reducing case handling time at the Compensation Board. It also made it possible for the board to make partial compensation decisions in order to compensate victims faster (Act no. 629, on State Compensation 2013). This was not part of the Government’s original policy action, but spoke to the issue of compensation that Marlene had also raised concerns about.

The third component, regarding victims’ role in the criminal justice process, was not new. It had been considered prior to Marlene’s opinion piece but had never been realized. Following the policy action plan, it was now examined by an expert panel. However, their report from November 2014 never resulted in any policy action (Ministry of Justice 2014).

In line with a NPF and PET approach, these three responses illustrate how the government as a “macro level” institution (cf. Peterson 2018) interfered at the meso level because its attention was drawn to competing policy ideas following the focusing event of Marlene’s opinion piece. The way that Marlene’s piece was appropriated and used by stakeholders thus “forced” the government to put the issue of victim support on their agenda.

Legislative Positions and Alignments

As the public debate on victim policies following the Marlene case got translated into hands-on politics, the interests and motives behind various stakeholders’ positions clearly reflected specific policy interests. We draw on the insights from the Advocacy Coalition Framework recognizing that different coalitions of stakeholders construct their own narratives in their striving for change (Jones et al. 2014). We see three primary arguments: support for victims, support for offenders, and a balancing voice. The third line of argument was presented by a few groups trying to balance the needs of both victims and offenders. Two stakeholders (The Association of Danish Regions and PTU—an association for people disabled from polio and accidents) adopted this latter balancing approachFootnote 11. They welcomed the proposals for “helping victims” while at the same time pointing to the fact that released offenders often have problems with economic debt that may increase recidivism. Therefore, they advised against generating income for the victims’ fund by fining offenders more than was already the case. PTU commented that victims should receive “support” and “respect and acknowledgment,” though not “at the expense of others,” by which they probably meant the offenders.

Groups that had the offender as their primary interest also protested against the fact that offenders should pay into the victims’ fund. The National Association of Defense Lawyers commented that “criminality shouldn’t be taxed”; The Council for Traffic Safety as well as FDM (the largest association of car owners in Denmark) protested against fining minor road traffic act offenses in which there were no “real” victims involved (The Legal Affairs Committee 2013).

The inclusion of traffic offenders was an interesting development also from an NPF perspective, since it seemed to expand the issue of what kinds of offenses should be fined for the benefit of a victims’ fund. This expansion of the “scope of conflict” triggered some contestation among certain interest groups since traffic offenders were not automatically seen as deserving this financial burden. However, the expansion still empowered politicians to include this previously unidentified group as contributors to the victims’ fund.

Opposing this, interest groups speaking for victims of violence, e.g., Hjælp Voldsofre (Help Victims of Violence) and Joan-Søstrene (the Joan Sisters), found the government proposal to be timely, since victims had recently experienced great financial cutbacks in favor of offenders (ibid). Victims’ organizations did not reject the “getting tough” rhetoric against offenders. As such, they confirmed what has elsewhere been labeled as an alliance between victims’ organizations and governments (Elias 1986).

In terms of impact, the timing of the opinion piece was right. It tapped into a decade of growing political attention to victims of crime. This had generated among others: expanded legal representation for victims (Act no. 558 2005), duty for police and prosecutors to inform and counsel victims (Act no. 517 2007), and notification of victims in regard to, i.e., the offender’s release from prison (Act no. 412 2011), as well as a commission report considering whether victims could testify before the offender at trial (Ministry of Justice 2006) and a task force report on increased action vis-à-vis victims of crime (Ministry of Justice 2010). Without this growing attention, the piece would probably not have been able to pave the way for policy actions such as a victims’ fund, which had previously not found political backing.

Concluding Discussion

On the surface, Marlene was successful in her endeavor. She caused a public debate and several legislative initiatives followed. On closer examination, however, her expressed needs were met only to a limited extent. Victims got the right to be notified of their offender’s public appearance, but they did not obtain better conditions regarding financial, social, and medical health as she had called for. A victims’ fund was established, but it did not entail the kind of help for victims that she advocated. The revenue from the fund does not support individuals, and it is used for research and program support, which was not her concern. Marlene herself pointed this out, as she was not enthusiastic about the prospect of the victims’ fund for research and projects instead of individual help. “Then victims are back where they started,” she commented in a national newspaper in 2013 (Hansen 2013).

Politicians tend to believe that media coverage mirrors public interest, but as we have seen and as Van Aelst, Thesen, Walgrave, and Vliegenthart point out, “When political actors take over media issues, they often do so on their own terms and with clear strategic goals” (Van Aelst et al. 2014: 210). So, while the case study on the one hand demonstrates how a single victim can access and influence policy and legislation, it also illustrates how her story was edited, shaped, and captured by politicians’ own agendas. This left her with a legislation output she never asked for and with no legislation aimed at her main concerns.

Walklate (2012) argues that the politicization of victims has resulted in an increasing use of emotional rhetoric when individual cases are addressed. Emotions provide politicians with the necessary capital to pursue specific agendas, as also indicated in our case study. Characteristically, emotions are targeted at individual victims’ cases and thus, in Walklate’s terms, constitute individual compassion rather than collective suffering (ibid). This construction of individualized victimhood marks a development away from the 1960s, when victimhood was addressed as a socio-structural problem (Goodey 2004). Walklate (2007: 206) has argued that single-issue campaign groups have made the field of victim policy even more complex and politicized. Single issues have often proven to be more compelling for politicians and the media alike, as is also the case in the present study. The focus on the individual needs of specific, delimited categories of victims, however, carries the risk that other kinds of victims are overlooked, potentially leading to unequal treatment (Groenhuijsen 2014). The attention given to the case of Marlene also points to the more general notion of some victims being heard while others are not. As our analysis has demonstrated, the emergent narrative victimology seems to be a fruitful tool in contributing to a deeper understanding of the mechanisms that qualify a victim to become a high profile individual victim and to embrace a victim identity (Rock 2002 in Walklate et al. 2019).

It has been argued that definitions of victims’ needs are often based on the available programs and resources, rather than on practice and experience (Goodey 2004; Elias 1986; Hall 2009). Dunn (2004) similarly argues that the support measures at hand become defining for victims’ policies instead of the other way around. This also seems to be our case. The victims’ fund could only be financed by including fines for even minor traffic offenses, and, in turn, traffic victims necessarily had to be constructed as one of the victims’ fund’s main targets. In this way, traffic victims only became politically important at the point when they had a role to fulfill in their legitimization of the funding sources.

By bringing together different theoretical perspectives on policy narratives, the analysis has highlighted the multiple levels of public policy processes involved in the Marlene case. The analytical framework of NPF has brought forth how Marlene’s opinion piece succeeded in moving from a micro level story that engaged individual readers to a meso level narrative engaging multiple stakeholders who competed to define victims’ needs and rights. The PET has added a further layer to our understanding of why and how the case of Marlene and the debate it spurred activated a macro level political institutional response from the Danish government. This seems to confirm one of the points of PET, in the sense that even though policy preferences at the macro level tend to be relatively stable, competing narratives at the meso level may encourage shifts in government attention. This may explain why the establishment of a victims’ fund that had not previously had political backing suddenly became a reality.

We have also seen how the framing of an individual case affected the specific regulation and took away focus from the structural level, such as the governmental victim support system at large. To some extent, the case study demonstrates that victim policy processes based on an individual case tend to focus on only selected aspects of the specific case in question. In this sense, the initiative about informing victims about TV programs in which their offender might participate while serving time is illustrative.

Shore and Wright (1997: 3) quote Aidan White’s concern that citizens are “becoming alienated from an increasingly remote and commercialized policy-making process.” An example of this alienation refers to the fact that politicians recurrently overlooked Marlene’s attempt at seeing herself as a forceful protagonist. The policy actions defined her and other victims as being vulnerable and weak. Thus, they were not responding to her own construction of herself as being a “warrior” in addition to being a “victim.” Apparently, the role of a warrior who has to fight the system does not fit into an appropriate policy ideal of a “helpless” victim. This rejection of Marlene’s self-image might be connected to politicians’ perceived role as guardians of—or at least with some kind of responsibility for—a “well-functioning” welfare system. In this way, what victims coin as their “reality” is redefined by policy actors. As discussed above, this may be one reason that the policy outcomes that Marlene wished for did never really materialize.

The case of Marlene confirms previous research pointing to the interplay between media priorities and political action (Van Aelst et al. 2014; Walgrave et al. 2017). The hypotheses for political agenda setting are fulfilled in the sense that the opinion piece takes up an obtrusive issue: “Offenders are put before victims” in Denmark. Throughout Marlene’s story, it is given negative coverage, pointing out a domestic policy issue that calls for problem solving, and it clearly addresses a political actor with responsibility and agency to act (Walgrave and Van Aelst 2006). Regarding the latter, Marlene did not point out one political actor, but the fact that she created a media storm with such a basic critique seemed to make all political parties struggle to show their support. The majority of the parties in parliament were even involved in legislative initiatives.

Our analysis of the Marlene case suggests that the narrative construction of the issue at stake might also play a role for setting the political agenda. As demonstrated through our analysis of the opinion piece, Marlene’s story embodied a number of elements that made the story “breathe” (as the term is used by Frank 2010). The narrative form of the piece strengthened the message by drawing on the in-built drama of the crime, a character-driven plot, and cultural archetypes such as victims, villains, and heroes, making it a classic policy narrative (Jones and McBeth 2010). The stakeholders included the media, politicians, interest groups, and celebrities (cf. ibid). These elements empowered the storyline, roles, and messages and presumably added to the emotional debate (equivalent to findings in Walklate et al. 2019). Furthermore, the “moral” of Marlene’s story also provided the government with ethical arguments for proposing legislative initiatives (cf. Jones et al. 2014). Helping victims of crime was a central part of Danish criminal policy prior to Marlene’s opinion piece as growing attention had been paid to victims of crime over the last decades. Policies supporting victims are often based on a victim-offender dichotomy and zero-sum discourse. Policies are thus aiming at helping either the victim or the offender, although the language and rationales behind the “help” varies. This narrative played into this victim-offender dichotomy in a new way as it seemed to change the discourse from victim or offender to victim over offender.

A point within NPF theory is that both the form and content of policy narratives may lend themselves to cross comparison (Jones et al. 2014). We therefore suggest that future research compares victim narratives across cultural and political settings. Research questions might include what these different contexts may mean for the development and impact of particular victim narratives on the policy process and outcomes for victims themselves. In particular, this study has pointed to the relevance of further research in the possible presence of an image of a “damsel in distress” among high impact or even high profile victims.

Additionally, we believe that one should pay particular attention to the legal contexts. Apart from Marlene’s story, the stories of high impact victims referred to here (including the laws individually named after particular victims) are based on incidents from common law jurisdictions. We ask to what extent narrative structural elements such as villains, plots, and solutions across legal contexts differ and how belief systems expressed through victim narratives may relate to the legal systems within which they are told.

Our analysis ends here, but the story continues. In February 22, 2018, the then Minister of Justice, Søren Pape Poulsen, authored an opinion piece in a national newspaper (Berlingske Tidende) under the heading “The victim is finally in the center.” The opening sentences were:

The case happened around six years ago by now. Nevertheless, I think that many Danes remember the completely absurd case regarding Marlene Duus. She was brutally attacked, maltreated with a heavy iron pipe and thrown out of a window from the third floor while unconscious. (Pape Poulsen 2018)

And in the piece, he concluded:

With our justice action plan, we have accomplished what I will call a step of historical significance in giving the victims of crime the proper treatment that they are entitled to. (Pape Poulsen 2018)

Most of the legislation and policy actions he referred to in the piece were unrelated to Marlene’s misgivings. Marlene’s narrative was—again—used to legitimize political action. Furthermore, the minister established himself as the hero who finally ensures that victims are taken care of, indirectly and falsely providing Marlene’s story with a happy ending. This is one among several examples of the use of the narrative after the time period that we have covered. Marlene’s story is thus still alive and will likely continue to serve as a reference for pursuing and legitimizing policy agendas not her own.

Notes

The quotes presented in this article are of our translation from Danish to English.

An opinion piece is a common genre in Danish newspapers and magazines. It is a longer article usually written by someone who does not work for the media house where it is published, but who is knowledgeable within a subject area of public interest either from a professional or a personal point of view.

According to Bruun (2012), journalist at Politiken, it appeared in print as well as online.

We employed “Ma?lene Duus” (as her name is spelled both as Marlene and Malene in various media) as search words.

For more information on Infomedia, see https://en.infomedia.dk/.

Newspaper stories are, however, partly dependent on TV news for setting the scene (e.g. Bartels 1996 in Van Aelst et al. 2014).

Witness Statement of Rosemary Anne Batty, Royal Commission into Family Violence, WIT.01 18.001.0001: para 5, 6th of August 2015

Although Rosie Batty was only indirectly harmed, her 11-year-old son was killed by his father.

Resonant of the ideal victim by Christie 1986

Including the research project that inspired this article

The arguments are visible in the consultation responses to the legislative proposal aimed at establishing a victims’ fund (The Legal Affairs Committee 2013).

References

Act no. 1284 (n.d.) Administration of Justice Act of 14/11/2018 (Denmark).

Act no. 412 on Amending the Administration of Justice Act on Compensation to Victims of Crimes by the State (Notification on Leave and Release etc. and Extending the Deadline for Reporting to the Police in the Case of State Compensation to Victims of Crimes) 2011, May 9 (Denmark).

Act no. 517 on Amending the Administration of Justice Act and the Code on Court Fees (Improving the legal status of victims of crimes) 2007, June (Denmark).

Act no. 558 on Amending the Administration of Justice Act (Improving the legal status etc. of rape victims and the appointment of lawyers for relatives of deceased in criminal proceedings against police personnel) 2005, June 14 (Denmark).

Act no. 603 on the Victim’s Fund 2013, June 12 (Denmark).

Act no. 629 on Amending the Administration of Justice Act and State Compensation Act for Victims of Crime (Extending the system of notifying victims and strengthening the framework for processing applications regarding victim compensation) 2013, June 12 (Denmark) (Historic).

Bacchi, C. (2009). Analysing policy, what's the problem represented to be? Frenchs Forest: Pearson Australia.

Beyer, J. (2013). Retorik i Retten – bedre forelæggelse, afhøringer og procedure. Copenhagen: Hanz Reitzels Forlag, 1. udgave.

Bill no. 166 on Amending the Administration of Justice Act and State Compensation Act for Victims of Crime (Extending the system of notifying victims and strengthening the framework for processing applications regarding victim compensation) 2013, February 28 (Denmark).

Bruun, C. E. (2012). Debat: Retten er ikke bare vores. Retrieved from: https://politiken.dk/debat/klummer/christofferemil/art5051256/Retten-er-ikke-bare-vores.

Christie, N. (1986). The ideal victim. In From crime policy to victim policy (pp. 17–30). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Crow, D. A., & Berggren, J. (2014). Using the narrative policy framework to understand stakeholder strategy and effectiveness: A multi-case analysis. In The Science of Stories (pp. 131–156). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dunn, J. L. (2004). The politics of empathy: Social movements and victim repertoires. Sociological Focus, 37(3), 235–250.

Duus, M. (2012). Får offeret også en chance til? Politiken. Retrieved from: https://politiken.dk/debat/art5454732/F%C3%A5r-offeret-ogs%C3%A5-en-chance-til

Elias, R. (1986). The politics of victimization, victims, victimonology and human rights. New York: Oxford University Press.

Flydtkjær, D. (2012). Debat: Vi svigtede Marlene Duus. BT, Retrieved from Infomedia.

Frank, A. W. (2010). Letting stories breathe: A socio-narratology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Garland, D. (2001). The culture of control, crime and social order in contemporary society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goodey, J. (2004). Victims and victimology, research, policy and practice. Pearson: Edinburgh.

Gray, G., & Jones, M. D. (2016). A qualitative narrative policy framework? Examining the policy narratives of US campaign finance regulatory reform. Public Policy and Administration, 31(3), 193–220.

Groenhuijsen, M. (2014). The development of international policy in relation to victims of crime. International Review of Victimology, 20(1), 31–48.

Hall, M. (2009). Victims of Crime: Policy and practice in criminal justice. Willan. 1 edition

Hansen, M. S. (2013). Voldsoffer: Ny fond hjælper os ikke. Kristeligt Dagblad. Retrieved from: https://www.etik.dk/forbrydelse-og-straf/voldsoffer-ny-fond-hj%C3%A6lper-os-ikke.

Hepp, A., Hjarvard, S., & Lundby, K. (2015). Mediatization: Theorizing the interplay between media, culture and society. Media, Culture & Society, 37(2), 314–324.

Jones, M. D. (2010). Heroes and villains: Cultural narratives, mass opinions, and climate change. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Jones, B. D., & Baumgartner, F. R. (2005). The politics of attention: How government prioritizes problems. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jones, M. D., & McBeth, M. K. (2010). A narrative policy framework: Clear enough to be wrong? Policy Studies Journal, 38(2), 329–353.

Jones, M. D., & Radaelli, C. M. (2015). The narrative policy framework: Child or monster? Critical Policy Studies, 9(3), 339–355.

Jones, M. D., Shanahan, E., & McBeth, M. (Eds.). (2014). The science of stories: Applications of the narrative policy framework in public policy analysis. Berlin: Springer.

Lauritsen, J. (2012). Vi kan undgå nye ofre. BT, Retrived from: https://www.bt.dk/krimi/chef-vi-kan-undgaa-nye-ofre.

McBeth, M., & Lybecker, D. (2018). The narrative policy framework, agendas, and sanctuary cities: The construction of a public problem. Policy Studies Journal, 46(4), 868–893.

McBeth, M. K., Shanahan, E. A., Arnell, R. J., Hathaway P. L. (2007). The Intersection of Narrative Policy Analysis and Policy Change Theory. Policy Studies Journal 35 (1):87–108

Meyer, C. (2012). Jeg vil forhindre, at der ikke bliver flere ofre. Politiken. Retrived from: https://politiken.dk/debat/art5417673/Jeg-vil-forhindre-at-der-bliver-flere-ofre

Meyers, D. T. (2016). Victims' stories and the advancement of human rights. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ministry of Justice. (2006). Report no. 1485 on the victim’s legal status in criminal proceedings. Retrieved from: http://jm.schultzboghandel.dk/upload/microsites/jm/ebooks/bet1485/pdf/bet1485.pdf.

Ministry of Justice. (2010). Report provided by the working group on strengthening actions towards victims of crimes.

Ministry of Justice. (2012a). Reply to question no. 642.

Ministry of Justice. (2012b). Press release: The Government wants to help victims of crime.

Ministry of Justice. (2014). Report no. 1549 on questioning the victim before legal proceedings in criminal courts. Retrieved from: https://www.ft.dk/samling/20141/almdel/reu/bilag/104/1436693.pdf

Motion for Government Action B 76 on Creating a Victims Foundation 2012 (Denmark). Retrieved from: https://www.ft.dk/ripdf/samling/20111/beslutningsforslag/b76/20111_b76_som_fremsat.pdf.

Motion for Government Action B 90 on Strengthening the Actions Towards Victims of Criminality 2012, presented 15th of May (Denmark). Retrieved from: https://www.ft.dk/samling/20111/beslutningsforslag/B90/som_fremsat.htm.

Østerbye, Kim (2012). Debat: Kald det Pladderhumansime. Berlingske Tidende. Retrieved from: https://faengselsforbundet.dk/wordpress/wpcontent/uploads/2015/12/berlingske.jpg.

Pape Poulsen, S. (2018). Offeret er endelig kommet i centrum. Berlingske Tidende. Retrieved from: https://www.berlingske.dk/kronikker/offeret-er-endelig-kommet-i-centrum.

Pemberton, A., Mulder, E., & Aarten, P. G. (2019). Stories of injustice: Towards a narrative victimology. European Journal of Criminology, 16(4), 391–413.

Peterson, H. L. (2018). Political information has bright colors: Narrative attention theory. Policy Studies Journal, 46(4), 828–842.

Rock, P. (2004). Constructing victims’ rights: The home office, new labour, and victims. Oxford: Oxford U. Press.

Roller, M. R. (2019). A quality approach to qualitative content analysis: Similarities and differences compared to other qualitative methods. Forum: Qualitative social research 20(3.)

Shanahan, E. A., Jones, M. D, Mcbeth M. K., Radaelli C. M (2018). Chapter 5: The Narrative Policy Framework in: Theories of the Policy Process, ed. Weible, C. M. & Sabbatier, P. A. New York: Routledge.

Shore, C., & Wright, S. (1997). Anthropology of policy, critical perspectives on governance and power. London: Routledge.

Stone, D. (2002). Policy paradox, the art of political decision making. New York: Norton.

Strömbäck, J. (2011). Mediatization and perceptions of the media's political influence. Journalism Studies, 12(4), 423–439.

Strömbäck, J., & Van Aelst, P. (2013). Why political parties adapt to the media: Exploring the fourth dimension of mediatization. International Communication Gazette, 75(4), 341–358.

The Legal Affairs Committee (2013). Consultation Responses, Bill 165 The Victims’ Fund 2012–2013.

Van Aelst, P., Thesen, G., Walgrave, S., & Vliegenthart, R. (2014). Mediatization and political agenda-setting: Changing issue priorities? In Mediatization of politics (pp. 200–220). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Walgrave, S., & Van Aelst, P. (2006). The contingency of the mass media's political agenda setting power: Toward a preliminary theory. Journal of Communication, 56(1), 88–109.

Walgrave, S., Boydstun, A. E., Vliegenthart, R., & Hardy, A. (2017). The nonlinear effect of information on political attention: Media storms and US congressional hearings. Political Communication, 34(4), 548–570.

Walklate, S. (2007). Victims, policy and service delivery. In S. Walklate (Ed.), Handbook of Victims and Victimology (pp. 203–239). Willan Publishing.

Walklate, S. (2012). Courting compassion: Victims, policy, and the question of justice. Howard Journal of Criminal Justice, 51(2), 109–121.

Walklate, S., Maher, J., McCulloch, J., Fitz-Gibbon, K., & Beavis, K. (2019). Victim stories and victim policy: Is there a case for a narrative victimology? Crime, Media, Culture, 1741659018760105.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers for valuable comments and suggestions, which helped us to improve the quality of the article.

Funding

We would like to thank the Danish victims’ fund for financial support for this research (Grant number 16-910-00046).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Asmussen, I.H., Adrian, L., Holmberg, L. et al. The Victim as Policy Agent? Exploring a Single Case from Denmark. Eur J Crim Policy Res 28, 79–95 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-020-09457-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-020-09457-0