Abstract

Background

Self-help habit reversal training and decoupling are effective in improving body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRBs). However, most studies to date on self-help techniques have assessed short-term effects only. The present study aimed to elucidate whether treatment effects would be sustained over a longer period of time.

Methods

We conducted a 2-year follow-up study of a cohort of 391 participants with mixed BFRBs who were initially randomized to four conditions (wait list control, habit reversal training, decoupling, decoupling in sensu). At post assessment, participants were allowed to use other treatment techniques, enabling us to explore treatment effects in those who continued to use the initial method only versus those who used additional techniques. The Generic Body-Focused Repetitive Behavior Scale (GBS-36) served as the primary outcome.

Results

Improvements achieved at post assessment were maintained at follow-up for all experimental conditions, with decoupling showing significantly greater treatment gains at follow-up relative to the wait list control group (last observation carried forward: p = .004, complete cases: p = .015). Depression at follow-up slightly improved compared to baseline and post assessment similarly across all conditions, arguing against “symptom displacement” to other psychopathological syndromes. Retention rates were similarly low across the four conditions (48.5–54.6%), making bias unlikely (but not firmly excluding it). Participants who adhered to the initial protocol until follow-up showed a pattern of improvement similar to those using additional techniques.

Discussion

Our study speaks for the long-term effectiveness of behavioral self-help techniques to reduce BFRBs, particularly decoupling. Of note, participants were allowed to use other self-help manuals after completing the post assessment; thus, randomization was removed. However, a minority of the participants chose this option.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRBs) such as trichotillomania and skin picking are conditions at the interface of psychiatry, dermatology (due to symptoms such as inflammation caused by skin picking), and—unbeknownst to many clinicians—dentistry (e.g., malocclusion of the front teeth caused by thumb sucking; lip-cheek biting). While no medication for BFRBs is currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration, effective cognitive behavioral treatments that are recommended by treatment guidelines (The TLC Foundation for body-focused disorders, 2016), most notably habit reversal training (HRT; Bate et al., 2011) and comprehensive behavioral treatment (ComB; Carlson et al., 2021), have been available for many years. However, only a few therapists have specialized in these conditions and both the knowledge gap and the treatment gap remain high (Capel et al., 2023; Jafferany et al., 2010; Marcks et al., 2006). This is aggravated by the tendency of those affected to abstain from seeking professional help due to shame or other reasons (Houghton et al., 2018; Weingarden & Renshaw, 2015). Recently, a number of self-help treatments have been released yielding promising results, most notably HRT (which is usually conducted by a therapist), decoupling (DC), and decoupling in sensu (DC-is; Moritz et al., 2011, 2012, 2022a, b, c; Weidt et al., 2015). As described in greater detail in the methods section, in HRT individuals are taught to adopt a rigid competing posture whenever they note the dysfunctional behavior or an urge to perform it. DC and DC-is are more dynamic, with the intention of reshaping the dysfunctional movements to a benign behavior.

Unlike in therapist-guided HRT, where there is solid evidence for the stability of treatment gains across different BFRB conditions (Azrin et al., 1980; Azrin & Nunn, 1973; Woods & Miltenberger, 1995), which is also true for HRT combined with other treatments (Keuthen et al., 2011), most trials on self-help interventions in BFRBs to date have used a rather short intervention period (3–6 weeks), so the maintenance of treatment gains thus remain elusive. We know of only one study (Weidt et al., 2015) that examined self-help (decoupling) over a longer period—6 months; that study found persistent improvements over the entire time span for decoupling. But, this study was confined to individuals with trichotillomania, and it is unknown whether the findings extend to a mixed BFRB sample. Thus, for the first time, we examined whether improvements in various BFRBs achieved after 6 weeks of treatment were still detectable 2 years later.

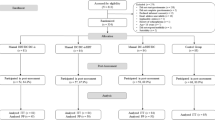

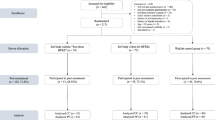

Methods

The present study represents a 2-year follow-up on a randomized controlled trial (Schmotz et al., 2023). Initially, 391 German-speaking individuals were randomized to one of the intervention groups (HRT, DC, DC-is) or to a wait list control (WLC) group (1:1:1:1). The main criteria for participation were the presence of at least one BFRB, age between 18 and 75 years, absence of acute suicidality, and absence of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Concurrent treatments were tolerated. The trial was registered with the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00022560) and approved by the local ethics committee (LPEK-0179 and LPEK-0502). Sociodemographic and psychopathological characteristics can be seen in Table 1.

Complete case analyses for the four conditions across time; * p < .05, *** p < .005, **** p < .001. Note. pre = baseline assessment, post = post assessment, fu = following assessment; DC = decoupling, DC-is = decoupling in sensu; HRT = habit reversal training; Wait list = wait list control condition

Participants were assessed at three time points (at baseline, after 6 weeks (post), and 2 years after baseline (follow-up)). Following completion of the post survey, participants were given the opportunity to download all manuals, but few participants did so (indicated below). Participants were reimbursed for their participation in the follow-up with 10€ (in the form of a voucher).

The study was advertised in online self-help forums (e.g., Facebook) as an unguided treatment study for people with BFRBs. Assessments were conducted online using Questback®. Informed consent was obtained electronically. The following scales were administered at all three time points.

Generic Body-Focused Repetitive Behavior Scale 36 (GBS-36, Primary Outcome)

The GBS-36 is derived from the GBS-8 and displays high test-retest realiblity and validity (Moritz et al., 2022). It measures the severity of the urge to perform a BFRB and the resultant impairment across various BFBRs (e.g., trichotillomania, skin picking, and nail biting).

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

The PHQ-9 captures the core depressive symptoms according to the DSM-IV with good to excellent reliability and validity (Kroenke et al., 2001).

At post and follow-up, participants in the experimental groups were asked to what extent they had used the manual, followed by questions on the subjective feasibility and effectiveness of the treatments based on items of the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8; Attkisson & Zwick, 1982).

The three self-help techniques were delivered in manualized form and can be retrieved here: https://www.free-from-bfrb.org/self-help/. In brief, all three interventions first instructed the participants to observe the situations in which their BFRBs occurred in order to identify triggers and critical time points for the dysfunctional behavior. In HRT, the participants were then instructed to interrupt their behavioral habit by a rigid competing (“frozen”) posture (e.g., clenching a fist, sitting on their hands), ideally for 1 to 3 min, whenever they noted the dysfunctional behavior or an urge to perform it. In DC, the original approach behavior is initially performed (e.g., directing the hand to the mouth in nail biting); that is, the individual is asked to begin the movement as closely as possible to the original behavior. Shortly before reaching the usual target of the dysfunctional behavior (e.g., the mouth when biting nails, the scalp when pulling hair), the participant jerks the hand away in a different direction with acceleration and tension (i.e., targeting another part of the body, such as the ear lobe, or moving the hand away from the body). This way, the individual becomes aware of their original problematic behavior and then unlearns and decouples it through repeated practice. Decoupling is aimed to divert the behavior or generate an irritation that may reach consciousness so that the affected individual can intervene. In contrast to HRT, the BFRB is not suppressed—it is redirected.

DC-is resembles DC. The only difference is that, in DC-is, approaching the target occurs only in the imagination—the second part of the behavior (i.e., the decoupling) is still actually performed as it is in DC. DC-is is intended to offer greater generalization of the effects compared to conventional DC as the exercise is not tied to one specific behavioral routine (Moritz, Rufer, et al., 2020). In DC and DC-is, the individual is instructed to practice the technique at least three times a day and in situations where the behavior usually occurs. Users are shown how to set a smartphone timer as a reminder.

Strategy of Data Analysis

We calculated mixed analysis of variance using SPSS 27. We used Cohen’s d (with pooled estimated population standard deviation) and ηp2 to measure effect sizes (small: d ≈ 0.2, ηp2 ≈ 0.01; medium: d ≈ 0.5, ηp2 ≈ 0.06; large: d ≈ 0.8, ηp2 ≈ 0.01).

Results

Completion and Strategy of Data Analysis

In view of the rather low completion rate at follow-up of 51.4%, which was similar across all four conditions (48.5–54.6%; χ2(3) = 0.75, p = .862), we chose a conservative over a less strict (e.g., expectation maximization) intention to treat (ITT) strategy. We adopted the last observation carried forward method (LOCF) for the ITT analyses along with complete cases (CC) analyses.

Although all participants, including those in the WLC group, were allowed to use all three techniques after the post assessment, only a minority of individuals in the WLC group used any of the techniques. Therefore, the percentage of participants who used any of the techniques between baseline and follow-up was higher in the experimental conditions (HRT: 80.8%; DC: 85.5%; DC-is: 87.3%, controls: 33.7%; χ2(3) = 76.22, p < .001). This will be taken into account in our subsequent analyses.

Short-term and Long-term Effects (Baseline to Post and to Follow-up)

For both the LOCF and CC analyses (LOCF: F (3, 387) = 3.046, p = .029, ηp2 = 0.023; CC: F (3, 290) = 4.75, p = .003, ηp2 = 0.047), DC (LOCF: p = .008; CC: p = .001) and DC-is (LOCF: p = .019; CC: p = .003) were superior to WLC at post assessment, while a statistical trend emerged in favor of HRT for the CC analysis (LOCF: p = .219; CC: p = .082). Overall, group differences were sustained at follow-up (i.e., baseline versus follow-up, LOCF: F (3, 387) = 2.824, p = .039, ηp2 = 0.021; CC: F (3, 197) = 2.215, p = .088, ηp2 = 0.033); the differences compared to the WLC group remained significant at follow-up only for the DC condition (LOCF: p = .004; CC: p = .015). The difference between HRT and controls bordered on significance for the CC analysis (p = .063; LOCF: p = .119); no effects relative to the WLC group occurred for DC-is (p = .221; LOCF: p = .104). The significant difference between the DC and the WLC group at follow-up was sustained even when we confined the WLC group to those participants who had used at least one technique after the post assessment (n = 27, p = .033).

Further exploration showed that group differences were not due to deterioration in the WLC group (see Fig. 1). In fact, BFRB symptoms decreased from baseline to post as well as from baseline to follow-up across all conditions (at least p ≤ .002, d > 0.45).

Maintenance Effects and Moderators (Post to Follow-up)

To assess maintenance of treatment effects after randomization was removed (i.e., post to follow-up), we conducted a 4 × 2 ANOVA with condition as the between-subject factor and time (post, follow-up) as the within-subject factor. Neither the effects of time (LOCF: F (3, 387) = 0.14, p = .710; ηp2 = 0.000; CC: F (3, 178) = 0.57, p = .452, ηp2 = 0.003) nor the interaction of the two factors achieved significance (LOCF: F (3, 387) = 0.91, p = .434; ηp2 = 0.007; CC: F (3, 178) = 0.81, p = .487, ηp2 = 0.014). Pairwise analyses corroborated that symptom severity persisted from post to follow-up across all conditions (at least p > .1, d < 0.24; all analyses were for completers).

Between post and follow-up, 30.8% of the participants in the experimental group continued to use the original technique only, 47.9% used another technique concurrently, and 21.2% did not use any of the techniques, with no differences pertaining to usage across experimental groups (χ2(3) = 4.18, p = .382). This enabled us to explore whether treatment effects were greater in those using more techniques relative to those not using any technique or using the original technique only. The 3 × 3 ANOVA of condition (without the WLC group as the response option “used original technique only” did not apply), and usage (no technique used, used original technique only, combination of techniques used) did not yield any significant main effects or interaction effects (p > .3, ηp2 < 0.035). In line with this, using more techniques was not correlated with outcome (baseline to post: r = .023, p = .708; baseline to follow-up: r = .026, p = .718).

Between-group Effects on Depression

For the PHQ-9, a 3 × 2 mixed ANOVA with condition as the between-subject factor and time (baseline, post, follow-up) as the within-subject factor yielded a significant effect for time (LOCF: F (2, 774) = 3.67, p = .026, ηp2 = 0.009) but no interaction (LOCF: F (6, 774) = 0.21, p = .974, ηp2 = 0.002). Post-hoc analyses showed a general decline from baseline to post, t(390) = 2.12, p = .034, d = 0.107, but not from post to follow-up, t(390) = 0.66, p = .510, d = 0.033 (status of significance was similar for the CC analyses). No deterioration was identified until follow-up (Mbaseline = 8.42, Mpost =7.85, Mfollow−up = 7.64; CC analyses).

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that the effects of behavioral self-help interventions used to treat BFRBs—habit reversal training, decoupling, and decoupling in sensu—are sustained, at least in part, after 2 years. Between post assessment and follow-up, scores did not significantly change for any of the groups. Somewhat surprisingly, the differences between the DC and the WLC groups remained significant at follow-up even though the latter group received access to all of the techniques after completing the post survey (however, only a minority of individuals used the techniques). Depression scores were reduced from baseline to post similarly across all conditions and then stabilized for the follow-up, meaning that “symptom displacement” (i.e., a symptomatic shift of psychopathology to another psychological condition) is unlikely as this would have negatively affected scores on this rather global transdiagnostic indicator of suffering.

Outcome was not associated with level of usage, that is, whether participants continued with the original technique, terminated usage, or combined techniques. This is somewhat unexpected in view of a prior study (Moritz et al., 2023) showing that the number of jointly used techniques correlated with improvement on BFRB symptoms. While there is evidence for a dose-response relationship in classical psychotherapy (Saxon et al., 2017), the effects are neither strong nor fully linear; with respect to self-help it is our experience that some patients seem to improve from, for example, decoupling (Moritz, Müller et al., 2020) after just a few sessions while others continue to use the technique on a regular basis without incremental improvement.

A number of limitations need to be acknowledged. First, our habit reversal protocol did not contain all the elements stipulated for the clinician-administered variant, which may have mitigated its potential. In addition, the retention rate was only slightly above 50%. This is comparable to other (online) studies that have longer time intervals between baseline and endpoint (de Hullu et al., 2017; Maas et al., 2018; Maeda et al., 2018). Yet, we need to acknowledge that other long-term follow-up studies in BFRB were more successful with re-assessment (Keuthen et al., 1998) thus calling for some explanation of low re-assessment rates. We attribute the high attrition to participants not checking their email used for the study after the post assessment, as we had encouraged individuals to create a new, anonymous email address when signing up for the study to ensure anonymity. Retention rates were, however, comparable across groups, indicating that the risk of bias was low (but not excluding it). The incentive of the monetary voucher was also meant to encourage the participation of individuals who did not benefit from the interventions initially and thus might have been less motivated to participate in a follow-up study (increasing the financial incentive might have improved completion rates to some extent). Still, we cannot fully reject the hypothesis that those with more treatment benefits felt more inclined to continue to participate. Further, the study relied on self-report alone and participants could use other self-help techniques after the post assessment; both these factors could dilute specific effects, but this enabled us to explore whether utilization of one or more of the techniques impacted the outcome after post assessment. Although the results were comparable for those who stopped using the technique, continued using it, or combined it with other techniques, these subsidiary results are weakened by the small sample sizes. However, we still recommend that individuals use the techniques in combination on a regular basis (see Moritz et al., 2023a, b). Another possible limitation is that utilization behavior was not tested in a random fashion. Yet, even if randomization had been maintained, most participants would likely have sought other treatment options in the meantime (e.g., psychotherapy, self-help books, medication). Perfect randomization for the sake of independence of treatment effects is hard to ensure even under a more rigorous study design.

Can self-help substitute for regular psychotherapeutic treatment? As long as no direct head-to-head comparisons have been conducted between self-help versus regular interventions, clinicians should stick to present treatment guidelines, which stipulate therapist-guided CBT. If this is not available (e.g., patient is on a wait list, patient has no insurance coverage) or to maintain improvement post treatment, self-help should be sought.

To conclude, the present study supports the feasibility and efficacy of self-help in BFRBs and the maintenance of the effects being sustained 2 years later. In view of residual symptoms in most participants, additional interventions (e.g. habit replacement; Moritz et al., 2023) need to be explored to augment treatment gains and to determine whether certain combinations of evidence-based techniques offer add-on effects.

References

Attkisson, C. C., & Zwick, R. (1982). The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Evaluation and Program Planning, 5(3), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-X.

Azrin, N. H., & Nunn, R. G. (1973). Habit-reversal: A method of eliminating nervous habits and tics. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 11(4), 619–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(73)90119-8.

Azrin, N. H., Nunn, R. G., & Frantz-Renshaw, S. (1980). Habit reversal treatment of thumbsucking. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 18(5), 395–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(80)90004-2.

Bate, K. S., Malouff, J. M., Thorsteinsson, E. T., & Bhullar, N. (2011). The efficacy of habit reversal therapy for tics, habit disorders, and stuttering: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(5), 865–871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.013.

Capel, L. K., Petersen, J. M., Woods, D. W., Marcks, B. A., & Twohig, M. P. (2023). Mental health providers’ knowledge of trichotillomania and skin picking disorder, and their treatment. Cognitive Therapy and Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-023-10381-w.

Carlson, E. J., Malloy, E. J., Brauer, L., Golomb, R. G., Grant, J. E., Mansueto, C. S., & Haaga, D. A. F (2021). Comprehensive behavioral (ComB) treatment of trichotillomania: A randomized clinical trial. Behavior Therapy, 52(6), 1543–1557. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BETH.2021.05.007.

de Hullu, E., Sportel, B. E., Nauta, M. H., & de Jong, P. J. (2017). Cognitive bias modification and CBT as early interventions for adolescent social and test anxiety: Two-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 55, 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2016.11.011.

Houghton, D. C., Alexander, J. R., Bauer, C. C., & Woods, D. W. (2018). Body-focused repetitive behaviors: More prevalent than once thought? Psychiatry Research, 270, 389–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.10.002.

Jafferany, M., Stoep, A., Vander, Dumitrescu, A., & Hornung, R. L. (2010). The knowledge, awareness, and practice patterns of dermatologists toward psychocutaneous disorders: Results of a survey study. International Journal of Dermatology, 49(7), 784–789. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04372.x.

Keuthen, N. J., O’Sullivan, R. L., Goodchild, P., Rodriguez, D., Jenike, M. A., & Baer, L. (1998). Retrospective review of treatment outcome for 63 patients with trichotillomania. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155 (4), 560–561. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.155.4.560

Keuthen, N. J., Rothbaum, B. O., Falkenstein, M. J., Meunier, S., Timpano, K. R., Jenike, M. A., & Welch, S. S. (2011). DBT-enhanced habit reversal treatment for trichotillomania: 3-and 6-month follow-up results. Depression and Anxiety, 28(4), 310–313. https://doi.org/10.1002/DA.20778.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

Maas, J., Keijsers, G. P. J., Rinck, M., & Becker, E. S. (2018). Does cognitive bias modification prior to standard brief cognitive behavior therapy reduce relapse rates in hair pulling disorder? A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 37(6), 453–479. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2018.37.6.453.

Maeda, E., Boivin, J., Toyokawa, S., Murata, K., & Saito, H. (2018). Two-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial: knowledge and reproductive outcome after online fertility education. Human Reproduction, 33(11), 2035–2042. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dey293

Marcks, B. A., Wetterneck, C. T., & Woods, D. W. (2006). Investigating healthcare providers’ knowledge of trichotillomania and its treatment. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 35(1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070510010657a

Moritz, S., Treszl, A., & Rufer, M. (2011). A randomized controlled trial of a novel self-help technique for impulse control disorders a study on nail-biting. Behavior Modification, 35(5), 468–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445511409395.

Moritz, S., Fricke, S., Treszl, A., & Wittekind, C. E. (2012). Do it yourself! Evaluation of self-help habit reversal training versus decoupling in pathological skin picking: A pilot study. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 1(1), 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocrd.2011.11.001.

Moritz, S., Müller, K., & Schmotz, S. (2020). Escaping the mouth-trap: Recovery from long-term pathological lip/cheek biting (morsicatio buccarum, cavitadaxia) using decoupling. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 25, 100530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocrd.2020.100530.

Moritz, S., Gallinat, C., Weidinger, S., Bruhns, A., Lion, D., Snorrason, I., Keuthen, N., Schmotz, S., & Penney, D. (2022a). The generic BFRB Scale-8 (GBS-8): A transdiagnostic scale to measure the severity of body-focused repetitive behaviours. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy.

Moritz, S., Rufer, M., & Schmotz, S. (2020b). Recovery from pathological skin picking and dermatodaxia using a revised decoupling protocol. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, 19(11), 3038–3040. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.13378.

Moritz, S., Penney, D., Ahmed, K., & Schmotz, S. (2022c). A head-to-head comparison of three self-help techniques to reduce body-focused repetitive behaviors. Behavior Modification, 46, 894–912. https://doi.org/10.1177/01454455211010707

Moritz, S., Penney, D., Weidinger, S., Gabbert, T., & Schmotz, S. (2022b). A randomized controlled trial on a novel behavioral treatment for individuals with skin picking and other body-focused repetitive behaviors. The Journal of Dermatology. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.16435.

Moritz, S., Penney, D., Bruhns, A., Weidinger, S., & Schmotz, S. (2023a). Habit reversal training and variants of decoupling for use in body-focused repetitive behaviors. A randomized controlled trial. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 47, 109–122.

Moritz, S., Penney, D., Missmann, F., Weidinger, S., & Schmotz, S. (2023b). Self-help habit replacement in individuals with body-focused repetitive behaviors. JAMA Dermatology. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2167.

Saxon, D., Firth, N., & Barkham, M. (2017). The relationship between therapist effects and therapy delivery factors: therapy modality, dosage, and non-completion. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(5), 705–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0750-5

Schmotz, S., Weidinger, S., Markov, V., & Penney, D. (2023). Self-help for body-focused repetitive behaviors: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders.

The TLC Foundation for body-focused disorders. (2016). Expert consensus treatment guidelines. Body-focused repetitive behaviors. Hair pulling, skin picking, and related disorders. TLC Foundation.

Weidt, S., Klaghofer, R., Kuenburg, A., Bruehl, A. B., Delsignore, A., Moritz, S., & Rufer, M. (2015). Internet-based self-help for trichotillomania: A randomized controlled study comparing decoupling and progressive muscle relaxation. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(6), 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1159/000431290.

Weingarden, H., & Renshaw, K. D. (2015). Shame in the obsessive compulsive related disorders: A conceptual review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 171, 74–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAD.2014.09.010.

Woods, D. W., & Miltenberger, R. G. (1995). Habit reversal: A review of applications and variations. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 26(2), 123–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7916(95)00009-O.

Funding

None.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The trial was registered with the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00022560) and approved by the local ethics committee (LPEK-0179 and LPEK-0502).

Animal Rights

No animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moritz, S., Hoyer, L. & Schmotz, S. Two-year Follow-up of Habit Reversal Training and Decoupling in a Sample with Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors. Cogn Ther Res 48, 75–81 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-023-10434-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-023-10434-0