Abstract

Social anxiety is characterised by a bias to recall negative social autobiographical memories as well as anxious expectations about future social interactions. Neuroscientific research shows that a shared neural network underlies both temporal directions of autobiographical recall and future self-projections. Inspired by these findings, the current study tested the effectiveness of a Cognitive Bias Modification training to induce expectancies about the outcome of possible future social interactions (CBM-E). Its effects on interpretation bias, autobiographical recall and personal future projections were tested additionally. Participants read short social scenarios that could possibly happen to them in the future. Each scenario ended in word-fragment which, when completed, disambiguated the meaning of the scenario in either an optimistic or pessimistic way contingent on experimental condition. The CBM-E training was tested in 120 student participants and appeared effective in changing expectancies. The effect generalized to social interpretation bias (scrambled sentences). No direct effects of the training were found on autobiographical recall or future projections. However, participants trained to have pessimistic expectancies who had higher attachment anxiety showed a less positive interpretation bias related to the future. Furthermore, participants with high social anxiety reported less positive personal future projections when trained to have optimistic social expectancies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autobiographical memory contains memories of our personal experiences as well as semantic knowledge about ourselves and the world. Our autobiographical memories are strongly linked to our sense of self, and in turn, memories can be more or less accessible according to their relevance to our current self. The Self-Memory System model of autobiographical memory (SMS model; Conway 2005; Conway and Pleydell-Pearce 2000) proposes several components that are involved in the recall of autobiographical memories. First, the autobiographical knowledge base contains the memories of our personal experiences. These are organized along a hierarchy of generality from specific episodic memories to lifetime periods, and horizontally according to different themes (e.g., “relationships”). Second, the ‘working self’ consists of a complex interacting set of goals (e.g. “graduating from high school”) and self-images (e.g. “I am a persistent student”), that are rooted in the autobiographical knowledge base. The working self regulates the encoding and recall of autobiographical information. Memories that are relevant to our goals (e.g., being liked by others) and self-images (e.g., I am boring) are highly accessible. Third, the working self constantly interacts with executive processes, the last component, to encode and retrieve self-relevant memories stored in the autobiographical knowledge base.

If we assume that people suffering from psychopathology hold goals and self-images related to their disorder, the SMS would predict that disorder-relevant autobiographical memories would be highly accessible in both involuntary and voluntary recall. For involuntary recall, for example, this is clearly illustrated by the presence of intrusive memories in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Research has also focused on memory bias in social anxiety. For voluntary recall, research has identified high accessibility of disorder-congruent autobiographical memories in PTSD (Sutherland and Bryant 2005, 2008), prolonged grief (Maccallum and Bryant 2008, 2010), and social anxiety (Krans et al. 2013, 2017). Generally, there appears to be no convincing evidence for an implicit memory bias in social anxiety. However, explicit recall of threatening information, especially of autobiographical nature, appears to be influenced in social anxiety (Mitte 2008; Morgan 2010). For example, highly socially anxious students recalled more (negative) autobiographical memories about social interactions in response to emotional word cues as well as more social anxiety-related goals than students low in social anxiety (Krans et al. 2013). This pattern was replicated in a clinical sample. Social anxiety disorder (SAD) patients recalled more (negative) autobiographical memories of social interactions in response to emotional cue words compared to a demographically matched healthy control group. They also reported more social anxiety-related future goals and current self-images, supporting a temporal dimension of cognitive bias that spans the past, present and future (Krans et al. 2017). These findings are in line with cognitive models of SAD (Clark 2001; Clark and Wells 1995; Heimberg et al. 2010; Rapee and Heimberg 1997) which, taken together, converge on the idea that individuals with social anxiety have negative expectations and interpretations of (future) social situations and they encode and rehearse these negative experiences in post-ruminative processing, resulting in highly accessible negative autobiographical memories, which further support negative future expectations and interpretations, thereby completing the cycle. Thus, biased future expectations and autobiographical recall appear to be closely linked in social anxiety.

Currently, the relation between autobiographical recall and future projection is an increasingly important topic in memory research (e.g., Allé et al. 2018; Del Palacio-Gonzalez and Berntsen 2019; Hallford et al. 2018). In the neurocognitive literature, a large overlap has been described in neural networks of autobiographical recall and future projection of the self, which include prefrontal and temporal lobes with a central role for hippocampal regions (Schacter et al. 2008). Several studies have also shown a significant overlap in the cognitive mechanisms of recalling the past and projecting the self in the future. For example, the level of specificity with which suicidal and healthy participants recalled the past and imagined the future was found to be positively correlated, and experimental induction of memory retrieval style (generic or specific) affected also future projections (Williams et al. 1996). In a study on phenomenological characteristics of mental time travel, it was found that temporal distance and emotional valence behave similarly in autobiographical recall and future projections (D’Argembeau and Van der Linden 2004). Furthermore, an experimental manipulation of self-efficacy affected the specificity and valence of recall and future projection comparably, showing a causal link between the two temporal dimensions (Brown et al. 2012).

The current literature thus suggests that the temporal dimensions of mental time travel (i.e., recalling the past and imagining the personal future) are related to each other, and that both may play a role in social anxiety. However, up to now, most findings have been correlational in nature and therefore preclude causal interpretations. The main goal of the present study was to examine the causal effect of future social expectancies on the valence of autobiographical recall and future projections of social situations, as an operationalization of memory selectivity. This was done by experimentally manipulating expectancies of the outcome of possible future social scenarios for which we developed a future-oriented version of the Cognitive Bias Modification of Interpretation (CBM-I) training paradigm (Mathews and Mackintosh 2000). CBM-I offers a systematic computerized training that modifies an interpretation style (Hirsch et al. 2016). Typically, participants are presented with ambiguous written scenarios that consists of approximately three short sentences. In the last sentence, a crucial target is presented as a word fragment. Completing the word fragment resolves the ambiguity of the scenario in either a positive or a negative way depending on the experimental condition. By repeated presentations of this valence contingency, a positive or negative interpretation bias is induced. It has been shown that a CBM-I training successfully induced an interpretation bias (Mathews and Mackintosh 2000; Menne-Lothmann et al. 2014), and can even affect memory for previously encoded ambiguous social scenarios in a valence-congruent way (De Winter et al. 2018; Salemink et al. 2010).

In the current study, we created a CBM-Expectancy training (CBM-E) based on the CBM-I procedure to modify expectancies of the outcome of possible future social situations. We phrased social scenarios in the future tense and asked participants to vividly imagine these events happening to them in the future. The scenarios systematically ended in a positive/optimistic way or a negative/pessimistic way to create two experimental conditions. Our first research question was whether this training was effective in inducing an expectancy bias (optimistic vs pessimistic). We predicted that participants in the optimism condition would show a more positive expectancy bias than participants in the pessimism condition after the CBM-E training. Second, we tested whether expectancy bias would affect the valence of autobiographical recall and autobiographical future projections. We expected that participants in the optimism condition would recall autobiographical memories and future projections with a higher positive valence than participants in the pessimism condition.

In CBM research, the bias assessment procedure that is typically used to confirm the effectiveness of the CBM training is often highly similar to the training procedure (Salemink et al. 2010). Thereby changes in the bias could reflect a response bias rather than an actual change in the index bias. Applying a second measurement strategy increases the validity of the findings. Therefore, we tested whether the CBM-E training would affect interpretation bias measured with an implicit measure (scrambled sentences task). Because the CBM-E was based on the standard CBM-I procedure, we expected generalization of our training effects to interpretation bias. Specifically, we predicted that participants in the optimism condition would show more positive resolutions of social and future oriented scrambled sentences than participants in the pessimism condition.

Fourth, social anxiety is a developmental outcome of insecure attachment relationships (Manning et al. 2017). More specifically, if individuals lack trust in the availability of attachment figures’ support during distress, they respond to distress more anxiously or more avoidantly attached. More anxiously attached individuals seek support while constantly fearing new relational disappointments, which hyperactivates stress levels. Instead, more avoidantly attached individuals refuse to seek attachment figure support in an attempt to avoid further relational ruptures. This requires them to deactivate (negative) emotions (Cassidy 1994; Kobak and Bosmans 2018). Although anxious attachment is most strongly linked with social anxiety, both insecure attachment styles are linked with social anxiety symptoms. Importantly, insecure attachment has proven to moderate the effectiveness of symptom-focused interventions (Bosmans 2016). For these reasons, additional measures of social anxiety and attachment were explored as moderators of the CBM-E training effects.

Method

This study follows the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Social and Societal Ethics Committee of the KU Leuven (reference G-2014 11 096). All participants gave written consent to the inclusion of material pertaining to themselves, acknowledged that they cannot be identified via the paper, and data was fully anonymized. All mandatory health and safety procedures were complied with in the course of conducting this experiment.

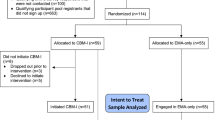

Participants

Participants were recruited from an undergraduate psychology student participant pool at the KU Leuven. They received course credits for participation. In total, 128 student participants were tested. Demographic information was obtained using a brief questionnaire (sex, age, university course, marital status, and nationality). Due to technical problems, data from eight participants were lost. The final dataset included 60 participants in each condition.

Materials

Individual Differences

Symptoms of social anxiety were measured with the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS; Liebowitz 1987). The LSAS contains 24 items that assess fear and avoidance for different social behaviours. Internal consistency in our sample was α = 0.96 for the total LSAS score, α = 0.93 for the fear subscale, and α = 0.91 for the avoidance subscale. Levels of depression were measured with the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al. 1996). This is a 21 item self-report questionnaire. Internal consistency in our sample was α = 0.85. The BDI-II was solely included to ensure that there were no baseline difference between the conditions on (clinical) depression. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21; Lovibond and Lovibond 1995) self-report questionnaire was administered to assess depression, anxiety and stress with 21 items. Internal consistency in our sample was α = 0.93 for the total DASS-21 score, α = 0.90 for the depression subscale, α = 0.77 for the anxiety subscale, and α = 0.89 for the stress subscale. The Experiences in Close Relationships Scale-Revised (ECR-R; Fraley et al. 2000) was administered to assess adult attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance. It is a 36 item self-report questionnaire. Internal consistency in our sample was α = 0.89 for the anxiety subscale, and α = 0.91 for the avoidance subscale.

Control Measures

The emotional impact of the CBM training was assessed with a mood questionnaire consisting of five items (optimism, anxiety, happiness, sadness, and arousal) rated on a Likert scale from 1 (‘neutral’) to 10 (‘as much as I can imagine’).

Autobiographical memory (AM) bias at baseline was measured by instructing participants to ‘Please recall a time when you attended a party or other social gathering where you hardly knew any other people.’ Participants were asked to recall this memory as vividly as possible, and then rate memory valence on a Likert scale running from -3 (very negative) to +3 (very positive). Additional Likert scales were administered measuring vividness (1 = ‘not vivid at all’, 9 = ‘very vivid’), and vantage perspective (1 = ‘through my own eyes’, 9 = ‘like through the eyes of an observer’). Only the valence score was analysed in this paper as a randomization check. Other measures were included for exploratory reasons and will not be reported here.

To account for possible demand effects, participants were asked what they thought the goal of the present study was with an open-ended question. Answers were rated as suspecting the goal if they mentioned any training effects on their memories.

Cognitive Bias Modification of Expectancy (CBM-E)

CBM-E Training

Participants were presented with different scenarios for which they were instructed to imagine themselves as the main actor in the scenario as vividly as possible. Scenarios were based on studies by Salemink et al. (2007), and Salemink et al. (2010). The scenarios were rewritten in the future tense and were presented in an introductory text as events that could possibly happen to the participants in the near future. Each scenario was preceded with a title (e.g., ‘New outfit’) and ended in a word fragment which the participants were asked to complete. The meaning of the scenarios remained ambiguous until the word fragment was solved. In the optimism condition, these resolved the scenario in a positive way, thereby creating a positive expectancy for the outcomes of future social events. In the pessimism condition, the word fragments resolved the scenario in a negative way, thereby creating a negative expectancy for the outcomes of future social events. An example of a scenario is ‘You will arrive at a party in a new outfit. When you walk in, everyone will look at you, and they will think that your outfit is…’, with the word fragment ‘gr_at’ (optimism condition) or ‘awf_l’ (pessimism condition). Participants were instructed to press the space bar as soon as they recognised the word, and then to press the missing letter from the word fragment. When correct, the completed word fragmented was shown on screen. When incorrect, an X appeared after which they saw the word fragment again for another attempt. After each scenario, a comprehension question appeared (e.g., ‘Will the people at the party like your new outfit?’) and participants had to respond K (for ‘yes’) or D (for ‘no’). If the participant answered correctly, the next scenario was presented. If they responded incorrectly, a red X appeared on screen and they received the question again.

The training started with three neutral practice trials. Thereafter, participants received eight training blocks, each containing (1) eight training scenarios with differing word fragments according to condition, (2) three neutral scenarios, (3) one positive target scenario, and one negative target scenario (to analyse the training effect). Thus, each block contained 13 scenarios. Neutral scenarios were the same for both conditions and were included to make the goal of the training less obvious. The positive and negative target scenarios were also the same for both conditions, and were critical to test the effect of the CBM-E on the expectancy bias. The order of the scenarios was randomized within blocks.

Training Effectiveness: RTs and Expectancy Bias Assessment

The time to resolve the positive and negative target scenarios from the training were recorded (reaction times) as a measure of training effectiveness. That is, if the training is effective, participants in the optimism condition should become faster in responding (e.g., quicker in pressing the space bar when the word fragment appeared) to positive scenarios than negative scenarios compared to participants in the pessimism condition.

An additional expectancy bias assessment was conducted before and after the training. Participants received 10 scenarios in a format similar to the training (e.g., ‘You will be invited to a night out in the local bar, but you will not know any of the people very well. When you approach the entrance, you will hear music and loud conversations, but as soon as you enter, it becomes…’) in random order, but here the ambiguity was not resolved by the word fragment (e.g., ‘qu_et’). As in the training, each scenario was preceded by a title (e.g., ‘The local bar’) and followed by a comprehension question. One practice trial was presented before the 10 assessment trials. After all scenarios were completed, participants were presented with the title of each scenario one by one in random order. Four statements relating to the scenario were printed below the title in random order. Participants were instructed to read each statement and rate how likely it was in relation to the scenario on a scale from 1 (‘very unlikely’) to 4 (‘very likely’). One target statement represented a positive expectancy (e.g., ‘When you enter the room, someone will come up to greet you warmly’), one represented a negative expectancy (e.g., ‘When you enter the room, everyone will stop and stare at you’), and two were foil statements that represented a more general positive and negative expectation. A positive expectancy bias index was calculated by subtracting the likelihood ratings of negative target statements from those of positive target statements for each participant (pre-training: α = .69; post-training: α = .69). The foil statements were assessed to test for generalization of the induced bias with a similar calculation (pre-training: α = .56; post-training: α = .44).

Training Effects

Autobiographical Memories and Future Projections

The modified Autobiographical Memory Test (M-AMT) was used to assess valence of autobiographical recall and future projections (Brown et al. 2013). The M-AMT is based on previous research on autobiographical recall and future thinking (e.g., Addis et al. 2007; Crovitz and Schiffman 1974). In a pilot study with 30 undergraduate students from the KU Leuven, participants were presented with 32 concrete neutral cue words (e.g., lemon, truck) and asked to recall a specific autobiographical memory (from 5 years or longer ago) and a possible specific future event (5 years or more into the future) which reflected a social situation in response to the cue word. Future events had to be plausible yet novel experiences, i.e., something that had never happened to the participant, to avoid overlap with a specific memory. Eight cue words were selected based on the briefest mean reaction times, which we took as an indication of feasibility of the task. These eight words were randomly assigned to one of two word-lists, each consisting of four cue words (shoes, insect, snake, kettle, and truck, lemon, hearth, dress). In the final M-AMT task participants were presented with one of the lists for memory recall (past condition) and the other word list for future projections (future condition). Order of time instruction (past/future) and word list (1 or 2) was counterbalanced across participants. Participants were given a maximum time of 3 min per response, thus the maximum duration of the M-AMT was approximately 25 min. After each response, participants were asked to provide a valence rating on a Likert scale from -3 (‘very negative’), 0 (‘neutral’), to +3 (‘very positive) for the memory or projection. The average valence ratings across responses in each condition (past, future) were calculated for each participant, reflecting memory bias and future projection bias, respectively. However, the internal consistency of this version of the M-AMT turned out to be poor, with α = .11 for the past condition and α = .15 for the future condition.

Interpretation Bias

To assess the effect of the CBM-E training on social and future interpretation biases we included a Scrambled Sentences Test (SST; Wenzlaff 1993). Participants were presented with 20 scrambled sentences in random order. Ten of these sentences reflected social situations (e.g., “/people/I’m/new/with/confident/nervous”; from Standage et al. 2010) and ten reflected thoughts about the future (e.g., “/always/I/rarely/make/ahead/plans”; from Demeyer and De Raedt 2014). Participants were instructed to form grammatically correct sentences using five out of the six words in the sentence. Each sentence could be completed in either a negative or a positive way depending on the word that was left out. During the SST participants were instructed to keep in mind a nine-digit number (882045185, created by random number generation) which they were asked to recall after the SST. This provided a cognitive load which should elicit more automatic (and thereby more biased) responses on the SST. The number of positive solutions were summed per participant for the social and future sentences separately as indices for social (α = .88) and future-related (α = .82) interpretation biases, respectively.

Procedure

After reading and signing an informed consent form, participants completed a demographic questionnaire, the LSAS, the BDI-II, DASS-21, and ECR, in this order. They then completed the mood ratings, and the baseline autobiographical memory item. Participants were alternatingly assigned to the optimism or pessimism condition to ensure an equal number of participants in each condition. After the second bias assessment, mood ratings were provided again. Because the CBM training could have mood effects and these could affect responses on outcome measures as well, a distracter task (a simple version of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; Grant and Berg 1948), was presented after the second bias assessment, and then mood ratings were taken a third time. Then, participants completed the M-AMT and the SST, respectively. To conclude, participants were asked about their perceived goal of the study (demand question). After study completion, participants were debriefed and thanked for their participation. Participants were tested individually in a lab cubicle. All measures were presented on a Dell Latitude laptop using Inquisit software (version 4.0.9.0), except the M-AMT which was delivered in person by a trained Masters level student.

Results

Descriptive statistics of individual differences, control variables, and direct and generalized training effects are reported in Table 1.

Participants

Chi square analyses and independent samples t-tests showed there were no significant group differences in gender distribution (10 men and 50 women, and 9 men and 51 women in the optimism and pessimism condition, respectively), age (M = 19.97, SD = 2.30 and M = 20.27, SD = 3.74 in the optimism and pessimism condition, respectively), university course (49 psychology and 10 other, and 55 psychology and 5 other in the optimism and pessimism condition, respectively), or marital status (57 single and 3 other in both conditions), all p > .15. There was a significant difference in the distribution of nationality, with relatively more Belgians (48) than non-Belgians (7 Dutch and 5 other) in the pessimism condition compared to the optimism condition (58 Belgians and 5 Dutch), χ2(2) = 8.72, p = .01.

Individual Differences

Baseline group differences in social anxiety (LSAS total score, fear subscale, avoidance subscale), depression (BDI-II, DASS-21 depression scale), anxiety and stress (DASS-21 anxiety and stress subscales), and adult attachment (ECR anxiety and avoidance subscales) were tested with independent samples t-tests. There were no significant group differences, all t < 1.95, all p > .05, except for the ECR scales. Attachment anxiety was marginally significantly higher in the pessimism condition, t(118) = 1.95, p = .05, and attachment avoidance was significantly higher in the pessimism condition, t(118) = 2.04, p = .04. This was due to two outliers in the pessimism condition, with scores higher than three times the standard deviation above the group mean. These cases did not have outlying scores on any of the dependent variables (SST or M-AMT). DASS-21 scores were entered as covariates in the analyses which tested the effectiveness of the training and the effect of training on the interpretation bias and valence of autobiographical memories and future projections. This was done because depression, anxiety and stress may plausibly influence the effect of the training. The DASS-21 can be entered as a covariate because there are no significant group differences at baseline (Miller and Chapman 2001), and controlling for the covariate can therefore increase statistical power.

Control Measures

A 3 (Time: pre-CBM, post-CBM, post-filler) × 2 (Condition: optimism, pessimism) mixed model repeated measures MANOVA was run with the mood items as multiple dependent variables, Time as a within-subject variable and Condition as the between-subjects variable. Multivariate tests showed a main effect of Time, F(10, 109) = 7.72, p < .001, Cohen’s f = 0.85, suggesting that the CBM training affected mood across conditions. Univariate tests showed significant Time effects for all mood items, smallest F > 4.14, largest p < .02, smallest f > 0.18. Pairwise comparisons (significance level of α = 0.05) showed that, across conditions, optimism, anxiety, and happiness decreased significantly from pre-CBM to post-CBM, all p < .01, but did not change from post-CBM to post-filler, all p > .12. Sadness decreased from pre-CBM to post-CBM, and decreased further from post-CBM to post-filler, both p = .03. Arousal decreased from pre-CBM to post-CBM, p = .03, but returned to baseline levels at post-filler, p = .91. There was no significant main effect of Condition, F(5, 114) = 0.72, p = .61. The Time × Condition was not significant, F(10, 109) = 1.78, p = .07. Importantly, independent t-tests showed that post-filler mood was comparable between the two conditions for all mood items, largest t < 1.01, smallest p > .31. Thus, it was unlikely that any mood effects of the training were responsible for training effects.

Independent t-tests showed no significant differences between conditions on the valence of the autobiographical memory at baseline, t(118) = 0.12, p = .91.

In the optimism group, there were three participants who suspected that the CBM training was aimed at making them more positive. In the pessimism group, two participants suspected that the CBM-training was aimed at making them more negative. This difference was not significant, χ2(1) = 0.21, p = .65. In each group, the number of participants that suspected the goal of the study was low. All analyses were rerun without these five participants but the pattern of results was similar. Therefore, it was decided not to exclude their data from the analyses.

Training Effectiveness: RTs and Expectancy Bias Assessment

Training RTs

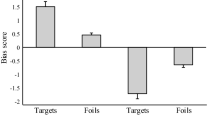

Reaction times (RTs) to positive and negative target scenarios were analyzed as a measure of training effectiveness. In total, 13.20% of trials were excluded, which were trials with incorrect answers either to the word fragment (55.56% of total excluded trials) and/or the comprehension question (44.44% of excluded trials). No trials needed to be excluded based on extremely short (< 200 ms) or long RTs (M + 3SD), M = 1757.78 ms, SD = 1984.05 ms. A 2 (Target: positive scenario vs negative scenario) × 2 (Condition: optimism vs pessimism) mixed model ANCOVA was run with reaction times (in ms) as the dependent variable, Target as a within-subject variable, Condition as a between-subjects variable, and DASS-21 subscale scores as covariates. There was no significant main effect of Condition, F(1, 115) = 1.78, p = .19, thus, average reaction times during the training were comparable in the two conditions. There was no significant main effect of Target, F(1, 115) = 1.57, p = .21, indicating that across conditions participants responded equally fast to positive and negative target scenarios. Importantly, the Target × Condition interaction was significant, F(1, 115) = 24.62, p < .01, f = 0.46, see Fig. 1. Because the covariates (DASS-21) were not significantly related to reaction times in the ANCOVA (all p > .17), these were not included in the follow-up tests.

Paired samples t-tests showed that participants in the optimism condition were significantly faster in responding to positive targets relative to negative targets, t(59) = 4.53, p < .01, d = 0.86, whereas participants in the pessimism condition were significantly faster in responding to negative targets than positive targets, t(59) = 2.19, p = .03, d = 0.36.

Expectancy Bias Assessment

The effect of the training on the expectancy bias was tested by comparing the change in the expectancy bias index between the two conditions. This was done with a 2 (Time: pre-CBM vs post-CBM) × 2 (Condition: optimism vs pessimism) mixed model ANCOVA with the positive expectancy bias index as the dependent variable, Time as the within-subject variable, Condition as the between-subjects variable, and the DASS-21 subscale scores as covariates. There was no significant main effect of Time, F(1, 115) = 2.10, p = .15. There was a significant main effect of Condition, F(1, 115) = 16.92, p < .01, f = 0.38, showing a more positive expectancy bias across time in the optimism condition compared to the pessimism condition. Importantly, the Time × Condition interaction was significant, F(1, 115) = 18.00, p < .01, f = 0.40 (see Fig. 2, Top). DASS-21 depression and stress were significant in the ANCOVA (p = .003 and p = .043, respectively), therefore, these were included in the follow-up tests. Repeated measures ANCOVA within each condition showed that the positive expectancy bias did not change significantly in the optimism condition, F(1, 57) = 0.03, p = .857. However, positive expectancy significantly decreased in the pessimism condition, F(1, 57) = 8.67, p = .005, f = 0.39, indicating that, as intended, the manipulation resulted in a difference in optimism between the two conditions.

Top: Positive expectancy bias (likelihood of positive target statements minus negative target statements) before and after the CBM training in the optimism and pessimism condition. Bottom: Generalized Positive expectancy bias (likelihood of positive foil statements minus negative foil statements) before and after the CBM training in the optimism and pessimism condition. Error bars represent standard deviations

A similar analysis was run for the generalized positive expectancy bias (based on the general foil statements), with similar results. There was no significant main effect of Time, F(1, 115) = 0.90, p = .35. There was a significant main effect of condition, F(1, 115) = 5.14, p = .03, f = 0.21, showing a more positive generalized expectancy bias overall in the optimism condition. The Time × Condition interaction was also significant, F(1, 115) = 13.58, p < .01, f = 0.34 (see Fig. 2, Bottom). The DASS-21 depression scale was a significant covariate (p = .001) and was included in follow-up ANCOVAs. There was a significant increase in the optimism condition, F(1, 58) = 4.12, p = .047, f = 0.27, and a significant decrease in the pessimism condition, F(1, 58) = 4.59, p = .036, f = 0.28.

Training Effects

Autobiographical Memory and Future Projection Bias

Two ANCOVAs were run to test whether expectancy bias affected the valence of autobiographical recall and autobiographical future projections. Condition (optimism, pessimism) was the independent variable, the number of positive memories/future projections on the M-AMT the dependent variable respectively, and DASS-21 subscale scores were included as covariates. There were no significant differences between the two experimental conditions in the number of positive autobiographical memories, F(1, 115) = 0.45, p = .506, or future projections, F(1, 115) = 0.56, p = .456, on the M-AMT. These findings suggest that the CBM training effect did not generalize to biases in autobiographical recall or future projections for social situations.

Interpretation Bias

To test the effect of the CBM-E training on social interpretation bias, a one-way ANCOVA was run with Condition (optimism vs pessimism) as the independent variable, the number of positive solutions on the social items of the SST as the dependent variable, and DASS-21 subscale scores as covariates. The main effect of condition was significant, F(1, 115) = 4.04, p = .047, f = 0.19, and indicated a more positive interpretation bias in the optimism condition. An ANCOVA was run with the mean number of positive solutions for the future items on the SST as the dependent variable. This indicated no significant difference between the two conditions, F(1, 115) = 0.74, p = .39.

Moderation by Social Anxiety, Attachment Anxiety and Attachment Avoidance

It was tested whether social anxiety or attachment moderated the relationship between the training and the memory/future projection bias (Table 2) and interpretation biases (Table 3). The DASS-21 subscales correlated significantly with each of the moderators and were therefore not included in these regression models. The first block always contained the valence rating of the autobiographical memory at baseline. The second block added a dummy variable for experimental condition. The third block added the moderator (LSAS total score, ECR anxiety, or ECR avoidance). Finally, the interaction term between condition (dummy variable) and the standardized scores of the moderator were entered to test the moderation effect.

Interpretation Bias (SST)

There was no significant moderation of the relation between the CBM-E training and interpretation bias for social sentences on the SST. Attachment anxiety was the only significant moderator of the relation between the CBM-E training and the interpretation bias for future-related sentences on the SST. The interaction equation indicated that higher attachment anxiety was related to fewer positive interpretations of future-oriented sentences in the pessimism condition than in the optimism condition (see Fig. 3, Top).

Memory and Future Projection Bias

There was no significant moderation of the relation between the CBM-E training and valence of autobiographical memories on the M-AMT. Social anxiety was the only significant moderator of the relation between the CBM-E training and the valence of future projections on the M-AMT. The interaction equation indicated that higher social anxiety was related to fewer positive future projections in the optimism condition than in the pessimism condition (see Fig. 3, Bottom).

Discussion

The current experiment aimed to test the effectiveness of a CBM-E training designed to alter future expectancies in the social domain (expectancy bias) in an unselected student sample. Furthermore, we aimed to test the effect of this training on the valence of autobiographical memory recall and future projections. The standard CBM-I training (Mathews and Mackintosh 2000) was adapted to reflect possible future scenarios in order to test the effectiveness and effects of a CBM-Expectancy training (CBM-E). Relative differences emerged between the optimism and pessimism condition, indicating that the CBM-E training worked as intended. That is, participants in the optimism condition responded faster to positive than negative target scenarios, whereas the reverse was true for participants in the pessimism condition. Furthermore, a positivity bias index showed a reduction after training in the pessimism condition (i.e., becoming less positive about the future scenarios) but not in the optimism condition. The fact that participants in the optimism condition did not increase in positive expectancies indicates that the training could be strengthened further, e.g., by means testing adapted instructions, revised items, and length of training. The training induced a more general expectancy style as more general positive foil statements were rated more likely in the optimism group, whereas the pessimism group became more pessimistic in general according to the foil statements in the bias assessment.

The training affected social interpretation bias, assessed with an indirect measure (scrambled sentences), showing more positive social interpretations in the optimism condition as compared to the pessimism condition. This is an important finding because CBM training effects have been critiqued (see Jones and Sharpe 2017) because bias assessments are very similar in procedure to the actual training, making is possible that a simple response bias related to the format is trained rather than an actual bias. The current finding indicates that the training affected the actual bias at least to some extent, beyond a mere response bias effect. However, no such effect was found for future-related scenarios. This may indicate that the intended future aspect of the CBM-E training is not strong or clear enough for participants. If that is the case, our CBM-E probably functioned as a standard CBM-I.

In contrast to predictions, the training did not have an impact on the valence of autobiographical recall and future projections as no group differences were found on the M-AMT. This could indicate that future expectations (or interpretation style) do not directly and causally affect autobiographical time travel in terms of valence. It is also possible that the cue words that were used in the M-AMT were not optimal for assessing any biases in autobiographical recall and projection. In contrast to earlier studies where such biases were found (e.g., Krans et al. 2013, 2017), the current cue words were neutral and concrete. It is possible that more abstract and emotional words are required in order to find biased responses. This remains to be tested. Finally, the internal consistency of this version of the M-AMT was poor in our sample. As far as we know, internal consistencies have not been reported for the M-AMT in earlier papers; therefore it is unknown at this stage whether it is a general problem of the M-AMT or one specific to the current study. Either way, the M-AMT may not adequately reflect negative autobiographical memory bias in the current sample and we are hesitant to draw firm theoretical conclusions based on the current data.

It is also possible that a cross-over from expectancy bias to the autobiographical memory/projection bias does occur, but only for a specific subgroup of people. For example, we found that participants with more attachment anxiety showed a less positive interpretation bias for the future (SST) when in the pessimism condition. This indicates that people with higher attachment anxiety may be vulnerable for spiraling into pessimistic future thinking once negative expectancies are introduced. This idea is in line with the frequently observed tendency to hyperactivate negative emotions in anxiously attached individuals (Brenning et al. 2012; Mikulincer et al. 2003). Further, participants with higher social anxiety produced fewer positive autobiographical future projections (M-AMT) when in the optimism condition. It is possible that confrontations with more ‘positive’ expectancies of outcomes of future social situations trigger pre-event rumination in this subgroup. Taken together, the question whether future expectancies causally influence interpretation bias, and the valence of autobiographical mental time travel does not seem straightforward and further studies in specific subgroups seem warranted.

This study had several limitations. First, the CBM-E training yielded mood effects, and these showed that even the optimism training was not experienced as very pleasant. Indeed, several participants complained that the training was long and tedious, and this is a problem that has been identified in other CBM studies too (e.g., Beard et al. 2011). It remains a challenge to develop a training which is persistent enough to change habitual cognitive styles without becoming overly repetitive and obvious. As to the specific nature of the current CBM-E, the data does not convincingly show that this adapted version was successful in changing future thinking. Rather, it seems that the training resembled more an interpretation bias training, which was not exactly what we intended. More research is needed to strengthen this CBM-E training’s focus on future thinking. This might require developing alternative training formats, such as virtual reality (e.g., Otkhmezuri et al. 2019). Third, the internal consistency of the current version of the M-AMT was very poor, and the cue words in were neutral and concrete, in contrast to the abstract emotional cue words that were used in earlier studies to assess autobiographical memory bias in social anxiety (Krans et al. 2013, 2017). This may have prevented us from finding any autobiographical bias. Fourth, results from CBM, and also our experiment, might be applied to clinical populations. As a first step, we tested the training in a student population. This is a necessary first step in translational research from both an ethical and practical view. Results may have been different in a patient population. For example, based on earlier findings it is possible that a memory bias would have been found in clinical populations. Further, it is possible that the training may not be strong enough to change expectancy biases in patients. These are empirical questions that remain to be tested. Furthermore, our sample consisted primarily of women, which further restricts generalizability of our results. Fifth, we did not include a follow-up assessment, although several CBM studies have shown that training cross-over effects take some time and are often not visible yet straight after the training. This may be another reason why we did not find the predicted effects on autobiographical valence.

Future studies are required to test the current (or an improved version of) CBM-E training in specific subclinical or clinical subgroups, as our data indicated that social anxiety and attachment anxiety moderate the effects of the training on different variables. It is also worthwhile to test the training effects with a version of the M-AMT that includes abstract emotional cue words. Moreover, further studies into an acceptable length of the training which maintains the training effect but reduces its tediousness are required. Follow-up assessments will also be informative to test whether any delayed effects occur. Another interesting avenue would be to study other memory characteristics than valence, such as vividness or vantage perspective. As vivid imagery is linked to emotion (Holmes and Mathews 2010), and vantage perspective plays a role in psychopathology (McIsaac and Eich 2004), it is possible that similar biases or distortions occur in future projections.

To conclude, we tested a new CBM-E training which seemed to work as intended. The training effect generalized to interpretation bias in the context of social information, but not future to expectations about one’s future. Hence, the training may have worked as a standard CBM-I training instead. No training effects were found on the valence of autobiographical recall or future projections. However, social anxiety and attachment anxiety appeared to moderate training effects and studies in these subgroups are required to uncover the interrelatedness of biases in expectancy, interpretation, and autobiographical mental time travel. The CBM-E training could be optimized in terms of its future orientation and length, and long-term effects will need to be assessed.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Open Science Framework at https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/ygkz9.

References

Addis, D. R., Wong, A. T., & Schacter, D. (2007). Remembering the past and imagining the future: Common and distinct neural substrates during event construction and elaboration. Neuropsychologia, 45, 1363–1377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.10.016.

Allé, M. C., Berna, F., & Berntsen, D. (2018). Involuntary autobiographical memory and future thought predicting hallucination proneness. Clinical Psychological Science, 6, 891–898. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702618785618.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Beard, C., Weisberg, R. B., & Primack, J. (2011). Socially anxious primary care patients’ attitudes toward Cognitive Bias Modification (CBM): A qualitative study. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 40, 618–633. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465811000671.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation.

Bosmans, G. (2016). Cognitive behaviour therapy for children and adolescents: Can attachment theory contribute to its efficacy? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 19, 310–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-016-0212-3.

Brenning, K., Soenens, B., Braet, C., & Bosmans, G. (2012). Attachment and depressive symptoms in middle childhood in pre-adolescence: Testing the applicability of the emotion regulation model of attachment. Journal of Personal Relationships, 19, 445–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2011.01372.

Brown, A. D., Dorfman, M. L., Marmar, C. R., & Bryant, R. A. (2012). The impact of perceived self-efficacy on mental time travel and problem solving. Consciousness and Cognition, 21, 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2011.09.023.

Brown, A. D., Root, J. C., Romano, T. A., Chang, L. J., Bryant, R. A., & Hirst, W. (2013). Overgeneralized autobiographical memory and future thinking in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 44, 129–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.11.004.

Cassidy, J. (1994). Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment relationships. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59, 228–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01287.

Clark, D. M. (2001). A cognitive perspective on social phobia. In W. R. Crozier & L. E. Alden (Eds.), International handbook of social anxiety: Concepts, research ans interventions relating to the self and shyness. Westport, CT: Wiley.

Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In R. G. Heimberg, M. Liebowitz, D. A. Hope, & F. R. Schneider (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment (pp. 69–92). New York: Guilford Press.

Conway, M. A. (2005). Memory and the self. Journal of Memory and Language, 53, 594–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2005.08.005.

Conway, M. A., & Pleydell-Pearce, C. W. (2000). The construction of autobiographical memories in the self-memory system. Psychological Review, 107, 261–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.107.2.261.

Crovitz, H. F., & Schiffman, H. (1974). Frequency of episodic memories as a function of age. Bulletin of the Psychosomatic Society, 5, 517–518. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03334277.

D’Argembeau, A., & Van der Linden, M. (2004). Phenomenal characteristics associated with projecting oneself back into the past and forward into the future: Influence of valence and temporal distance. Consciousness and Cognition, 13, 844–859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2004.07.007.

De Winter, S., Salemink, E., & Bosmans, G. (2018). Interpretation bias in middle childhood attachment: Causal effects on attachment memories and scripts. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 102, 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.12.004.

Del Palacio-Gonzalez, A., & Berntsen, D. (2019). The tendency for experiencing involuntary future and past mental time travel is robustly related to thought suppression: An exploratory study. Psychological Research, 83, 788–804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-018-1132-2.

Demeyer, I., & De Raedt, R. (2014). The effect of future time perspective manipulation on affect and attentional bias. Cognitive Therapy Research, 38, 302–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-013-9584-6.

Fraley, R. C., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 350–365. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.350.

Grant, D. A., & Berg, E. A. (1948). A behavioural analysis of degree of reinforcement and ease of shifting to new responses in a Weigl-type card-sorting problem. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38, 404–411. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0059831.

Hallford, D. J., Austin, D. W., Takano, K., & Raes, F. (2018). Psychopathology and episodic future thinking: A systematic review and meta-analysis of specificity and episodic detail. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 102, 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.01.003.

Heimberg, R. G., Brozovich, F. A., & Rapee, R. M. (2010). A cognitive behavioral model of social anxiety disorder: Update and extension. In S. G. Hofmann & P. M. Dibartolo (Eds.), Social anxiety: Clinical, developmental, and social perspectives (pp. 395–422). New York: Elsevier Academic Press.

Hirsch, C. R., Meeten, F., Krahé, C., & Reeder, C. (2016). Resolving ambiguity in emotional disorders: The nature and role of interpretation biases. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12, 281–305. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093436.

Holmes, E. A., & Mathews, A. (2010). Mental imagery in emotion and emotional disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 349–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.001.

Inquisit 4.0.9.0. [Computer software]. (2016).

Jones, E. B., & Sharpe, L. (2017). Cognitive bias modification: A review of meta-analyses. Journal of Affective Disorders, 223, 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.034.

Kobak, R., & Bosmans, G. (2018). Attachment and psychopathology: A dynamic model of the insecure cycle. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 76–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.018.

Krans, J., De Bree, J., & Bryant, R. A. (2013). Autobiographical memory bias in sociale anxiety. Memory, 22, 890–897. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2013.844261.

Krans, J., Peeters, M., Näring, G., Brown, A. D., De Bree, J., & Van Minnen, A. (2017). Examining temporal alterations in Social anxiety disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: The relation between autobiographical memory, future goals, and current self-views. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 52, 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.09.007.

Liebowitz, M. R. (1987). Social phobia. Modern Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry, 22, 141–173. https://doi.org/10.1159/000414022.

Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales (2nd ed.). Sydney: Psychology Foundation.

Maccallum, F., & Bryant, R. A. (2008). Self-defining memories in complicated grief. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 1311–1315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.09.003.

Maccallum, F., & Bryant, R. A. (2010). Impaired autobiographical memory in complicated grief. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48, 328–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.12.006.

Manning, R. P., Dickson, J. M., Palmier-Claus, J., Cunliffe, A., & Taylor, P. J. (2017). A systematic review of adult attachment and social anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders, 211, 44–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.020.

Mathews, A., & Mackintosh, B. (2000). Induced emotional interpretation bias and anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 602–615. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.109.4.602.

McIsaac, H. K., & Eich, E. (2004). Vantage point in traumatic memory. Psychological Science, 15, 248–253. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00660.x.

Menne-Lothmann, C., Viechtbauer, W., Höhn, P., Kasanova, Z., Haller, S. P., Drukker, M., et al. (2014). How to boost positive interpretations? A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of cognitive bias modification for interpretation. PLoS ONE, 9, e100925. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100925.

Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., & Pereg, D. (2003). Attachment theory and affect regulation: The dynamics, development, and cognitive consequences of attachment-related strategies. Motivation and Emotion, 27, 77–102. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024515519160.

Miller, G. A., & Chapman, J. P. (2001). Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843X.110.1.40.

Mitte, K. (2008). Memory bias for threatening information in anxiety and anxiety disorders: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 1134, 886–911. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013343.

Morgan, J. (2010). Autobiographical memory biases in social anxiety. Clinical Psychology Review, 20, 288–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.003.

Otkhmezuri, B., Boffo, M., Siriaraya, P., Matsangidou, M., Wiers, R. W., Mackintosh, B., et al. (2019). Believing is seeing: A proof-of-concept study on using mobile virtual reality to boost the effects of interpretation bias modification for anxiety. Journal of Medical Internet Research Mental Health, 6, e11517. https://doi.org/10.2196/11517.

Rapee, R. M., & Heimberg, R. G. (1997). A cognitive-behavioural model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 741–756. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00022-3.

Salemink, E., Hertel, P., & Mackintosh, B. (2010a). Interpretation training influences memory for prior interpretations. Emotion, 10, 903–907. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020232.

Salemink, E., Van den Hout, M., & Kindt, M. (2007). Trained interpretive bias and anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.03.011.

Salemink, E., Van den Hout, M., & Kindt, M. (2010b). Generalisation of modified interpretive bias across tasks and domains. Cognition and Emotion, 24, 453–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930802692053.

Schacter, D. L., Addis, D. R., & Buckner, R. L. (2008). Episodic simulation of future events: Concepts, data, and applications. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1124, 39–60. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1440.001.

Standage, H., Ashwin, C., & Fox, E. (2010). Is manipulation of mood a critical component of cognitive bias modification procedures? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48, 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.08.005.

Sutherland, K., & Bryant, R. A. (2005). Self-defining memories in post-traumatic stress disorder. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 591–598. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X64081.

Sutherland, K., & Bryant, R. A. (2008). Autobiographical memory and the self-memory system in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 555–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.03.008.

Wenzlaff, R. M. (1993). The mental control of depression: Psychological obstacles to emotional well-being. In D. M. Wegner & J. W. Pennebaker (Eds.), Handbook of mental control (pp. 239–257). Eaglewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Williams, J. M. G., Ellis, N. C., Tyers, C., Healy, H., Rose, G., & MacLeod, A. K. (1996). The specificity of autobiographical memory and imageability of the future. Memory & Cognition, 24, 116–125.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants for taking part in the experiment, students from KU Leuven (Pia Sophie Arras, Wesley Croymans, Gilke Leysen, Jasmien Aendekerck, and Hanne Jacobs) for their help with recruitment and data collection, and Dr. Helen Standage for sharing the future-oriented SST items.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Krans, Bosmans, Salemink and De Raedt declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Animal Rights

No animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Krans, J., Bosmans, G., Salemink, E. et al. Cognitive Bias Modification of Expectancies (CBM-E): Effects on Interpretation Bias and Autobiographical Memory, and Relations with Social and Attachment Anxiety. Cogn Ther Res 43, 1028–1042 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-019-10032-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-019-10032-z