Abstract

The team composition of a project team is an essential determinant of the success of innovation projects that aim to produce novel solution ideas. Team assembly is essentially complex and sensitive decision-making, yet little supported by information technology (IT). In order to design appropriate digital tools for team assembly, and team formation more broadly, we call for profoundly understanding the practices and principles of matchmakers who manually assemble teams in specific contexts. This paper reports interviews with 13 expert matchmakers who are regularly assembling multidisciplinary innovation teams in various organizational environments in Finland. Based on qualitative analysis of their experiences, we provide insights into their established practices and principles in team assembly. We conceptualize and describe common tactical approaches on different typical levels of team assembly, including arranging approaches like “key-skills-first”, “generalist-first” and “topic-interest-first”, and balancing approaches like “equally-skilled-teams” and “high-expertise-teams”. The reported empirical insights can help to design IT systems that support team assembly according to different tactics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In knowledge work, organizations’ success is increasingly dependent on team work, which, ideally, allows individuals to be more productive and creative than they could be on their own (Salas et al. 2018; Hall et al. 2018; Tebes and Thai 2018). An increasingly common approach to spur innovation capability is to assemble diverse teams that span organizational boundaries (Edmondson and Harvey 2018) and collaborate intensively in face-to-face settings. However, a perennial yet unsolved question is how to assemble teams with high chances of success – in particular, what kind of team compositions yield the best results (Bell et al. 2018). Prior research on team formation implies that the assembly phase fundamentally influences the team dynamics and processes that determine how teams achieve their objectives (Levine and Moreland 1990; Mathieu et al. 2014; Bell et al. 2018). While team formation more broadly refers to defining a team’s purpose, tasks, and rules, according to Gómez-Zará et al. (2020), team assembly refers to “the process of searching for, identifying, and choosing members for a team”.

Team assembly can be seen to represent one form of social matching (or ’matchmaking’), which as an application area of IT has been conceptualized as computer-aided identification and facilitation of new social connections between people (Terveen and McDonald 2005). In professional life, social matching looks into, for example, recruitment decisions and consideration of team compositions in work life, which both are characterized by high level of complexity and high cost of failure, especially when matching multiple actors (Olsson et al. 2019; Weller et al. 2019). While HCI and CSCW research has explored technological tools for facilitating team assembly (Gómez-Zará et al. 2019; Harris et al. 2019; Jahanbakhsh et al. 2017; Zhou et al. 2018), the important decision of who should team up is typically left to matchmaking experts like project managers, or HR specialists. Few digital tools have been adopted in day-to-day team assembly practice to support the identification of fruitful team compositions (Cappelli 2019). Even in research projects, the proposed solutions are often based on self-assembly (Harris et al. 2019; Lykourentzou et al. 2017), where people decide by themselves with whom to cooperate. To this end, this study focuses on experts who regularly assemble teams in various professional and organizational contexts. In this paper, they are referred to as matchmakers, even if in everyday life the term often refers to romantic matching.

Furthermore, we focus on the assembly of multidisciplinary innovation teams, which have been also named as “cross-boundary” (Edmondson and Harvey 2018), “cross-functional” (Love and Roper 2009) or “multifunctional teams” (Johnsson 2017). By definition, such teams aim to break boundaries associated with “differences in expertise and organization” in an attempt to solve problems or create new ideas (Edmondson and Harvey 2018). That is, individuals join newly assembled temporary groups with fluid membership, aiming to rapidly develop into high-performing units to take on unfamiliar projects (Edmondson and Harvey 2018). Activities that transcend organizational boundaries in order to share knowledge and create new ideas are often referred to as “open innovation” (Chesbrough and Schwartz 2007; Chatenier et al. 2010). Such cross-boundary innovation teams are relatively short-term (i.e., weeks or months, rather than years) and, hence, differ from long-term teams that are reasonably stable, functionally homogeneous, and typically bounded to one organization.

We consider the assembly of innovation teams particularly challenging and interesting in terms of social matching. First, such type of matchmaking is increasingly common, for example, in regional innovation ecosystem facilitation activities (Gryszkiewicz et al. 2016; Fecher et al. 2018). In this context, team assembly includes complex decisions, such as what features of individuals to consider in the team composition and how to balance the compositions across multiple teams. Assembling effective innovation teams across established organizational and disciplinary boundaries is notoriously challenging because of, e.g., possible conflicting interests among team members and the challenge to find time to co-create ideas with strangers (Rowe et al. 2008; Gryszkiewicz et al. 2016). Further, the context of innovation team assembly provides a sufficiently focused view on the broad topic of group formation that covers a variety of different organizational structures and organic groups (Harris et al. 2019). In contrast to virtual teams, for example, the question of team composition is arguably more central in the context of innovation teams that work intensively in face-to-face settings.

Our key premise is that assembling of innovation teams has become a common activity in certain organizational environments and that certain workers routinely conduct such activities (e.g., team coaches of innovation ecosystems or in higher education). Therefore, we assume that such expert matchmakers have formed certain practices —be they conscious and though-through processes and principles or intuitive habits —to reach effective team compositions (Harris et al. 2019). Considering the technical knowledge interest in CSCW and HCI, the endeavor to develop technology to support such practices calls for better understanding the matchmakers’ experiences and practices in this activity context. To this end, our focus is on user research aiming to understand the experiential and tactical aspects rather than, for example, evaluation of specific technological tools the matchmakers use. Only a few attempts have been made to qualitatively study the decision-making processes (Kale et al. 2019) and the possible roles for information technology to support matchmakers in their decision-making (Koivunen et al. 2019). Thus, we set the following research questions: (RQ1) How do matchmakers experience the assembly of innovation teams as professional matchmaking? (RQ2) What kind of practices have they established for this activity?

To this end, we gathered qualitative insight with one-to-one, in-depth interviews of 13 matchmakers who regularly assemble innovation teams in various organizational contexts. We contribute a qualitative account of the matchmakers’ experiences, principles and practices, thus shedding light on an emergent, yet understudied professional activity. To the best of our knowledge, empirical research on this topic is scarce, and there is little empirically grounded insight into research and development opportunities for IT supporting the studied activity.

2 Related Work

In the following, we first discuss the research on innovation teams and team assembly approaches, as well as position the activities that have been empirically studied in this conceptual landscape. We furthermore outline the research on computational support for team assembly, also underlining critical gaps between theory and practice.

2.1 Innovation Teams and Team Assembly Approaches

A team implies social interaction between two or more individuals who pursue shared goals or perform relevant organizational tasks (e.g., Kozlowski and Ilgen2006). The individuals might have different roles and responsibilities and are interdependent regarding the workflow and outcomes of the teamwork. Teamwork can be defined as interdependent social interaction between individuals with shared goals and values (Salas et al. 2013). The team composition – “a configuration of team member attributes” (Bell et al. 2018) – then affects the behavioral processes, functioning and performance of a team. Prior work posits that in the heart of teamwork are the abilities to, for example, make use of complementary capabilities, monitor each other to reduce errors and shift workload (Salas et al. 2018). Different classifications of team types have been conceptualized based on criteria such as size and structure of the team, or its role, task and lifespan (Hollenbeck et al. 2012). The present work focuses on innovation teams (Johnsson 2017; Edmondson and Harvey 2018; Gryszkiewicz et al. 2016; Fecher et al. 2018) that involve individuals with different backgrounds brought together to innovate new products, services, processes, and systems in the form of cross-functional and cross-boundary projects.

2.1.1 Team Composition

While a body of research covers what constitutes cognitive selection processes (Sadler-Smith 2016), the subjective experiences of intuition-based and deliberate choices in organizational group assembly settings remain poorly understood. The decision-makers in complex and dynamic environments of organizations face a high level of uncertainty (Edmondson and Harvey 2018) due to the inconsistency of organizational structures. This can hinder developing unified strategies for team composition. We argue that the compositions of innovation teams are characterized by needs for considering the possibly different interests of the involved organizations and individuals, and the team’s capability to perform and yield results relatively fast. Furthermore, the individuals who volunteer to apply to projects are typically rather early-career than experienced professionals, implying that their competences can be hard to articulate or compare.

In their seminal work, Mathieu et al. (2013) identified six types of team composition decisions (e.g., staffing a new team and simultaneously staffing multiple new teams). Relevant to our work, forming new teams can follow different principles when assembling a single team vs. multiple teams (adopted from Mathieu et al. 2013):

-

Single team formation refers to forming a team with the optimal combination of all team members;

-

Multiple team formation refers to forming multiple teams with the optimal combination of all team members;

-

Reconfiguration refers to forming multiple teams by reassigning or assigning multiple team members. Within a team, the operations include simply an addition, a subtraction or a replacement of a single member.

Team composition has been empirically linked to innovation (Richter et al. 2012), and different approaches can be considered when assembling teams for innovation projects (Somech and Drach-Zahavy 2013). For instance, aggregated individual creative personality is a summative approach where people with the ability to generate many alternative solutions to an open-ended problem are teamed up. Another approach is to team up based on functional heterogeneity – matching people from different disciplines and functions who have domain expertise. Notably, Hackman and Katz (2010) suggested that aggregating individual attributes would not predict the team’s characteristics.

Furthermore, approaches can be classified into individual-based and team-based approaches (Mathieu et al. 2014). While the first focuses on individual qualities with teamwork considerations (e.g., communication skills) and person-position fit, the latter is more holistic and aims at balancing distributional qualities of a team and complex mixing of individuals. Both strategies can utilize the traditional human resource KSAO framework – Knowledge, Skills, Abilities, and Other characteristics (Jayne and Dipboye 2004). In practice, team composition decisions usually consider both individual and team level KSAOs (Bell et al. 2018). In addition, a role-based approach called Belbin team roles has been developed to classify individual team members with specific work roles, such as coordinator, implementer and finisher. Such approach aims to help matchmakers to compose a group of people with complementary qualities (Belbin 2012).

A recent study investigated how team members are assigned to projects (Sankaran et al. 2019). Accordingly, on individual level, the importance of knowledge and skills is emphasized. Furthermore, interpersonal skills, capability of being a team player and ability to take leadership are considered even though they are hard to identify. A study by Sankaran et al. (2019) focused on long-term projects where new members are able to flexibly join and leave the project. In contrast, in our context of innovation teams, time-critical project teams are fully composed from the start with people who have applied to be part of the project. This is particularly important considering the way the teams are built, since talent often needs to be spread in a meaningful way across the teams.

Highly relevant to the present work, Hastings et al. (2018) used a team formation tool called CATME to compare criteria-based strategies with a random strategy. Surprisingly, they did not find differences in team performance or satisfaction under the tested conditions. The results contrasts with prior literature in terms of the relevance of team composition in the first place, and the authors discuss several possible explanations for this. First, the results might be influenced by an expectation effect caused by the students believing that all teams were created using the tool. The context was also acknowledged to differ from prior research (i.e., two computer science classroom courses). The tool stacks multiple criteria together, which means more complex compositions (8 or 13 criteria used to form teams, respectively). Alternatively, the CATME tool might have been ineffective; the authors found that the tool did not always match the instructors’ mental models regarding how skills ought to be distributed across teams. All in all, while the results may seem to suggest random assignment as a valid strategy, the authors themselves draw rather cautious conclusions. More importantly, the result suggests that instructors should not be so concerned about fine-tuning the configurations of a team formation tool. In our context and study data, we did not find that similar tools would be used. Rather, our findings highlight several handwork based approaches when assigning applicants to teams. Furthermore, the study indicates gaps of knowledge in terms of authentic settings of team assembly, also beyond the context of classrooms. The context of innovation teams arguably differs from that of classrooms, calling for further exploratory empirical research.

2.1.2 The Role of Diversity in Team Assembly

The importance of heterogeneity of individuals’ qualities is much discussed in literature. For example, the diversity of levels of expertise, skills and abilities can contribute to higher chances of knowledge breakthroughs and innovation (Baker 2015). Essential differences in human qualities include, for instance, surface-level (e.g., age, sex, ethnicity), behavioral and cognitive (e.g., personality traits, abilities, values and attitudes) differences (Haythorn 1953; Bell et al. 2018). According to the meta-analysis by Hülsheger et al. (2009), there seems to be a positive relationship between diversity in task-related attributes (e.g., profession, education, knowledge) and innovation. More specifically, composing individuals with dissimilar technological knowledge tends to improve creativity (Huo et al. 2019). It has been addressed that the individuals’ innovation capability (Sun et al. 2017) and demographic diversity (Tshetshema and Chan 2020) drive the innovation team performance. However, prior research tends to omit the multifaceted nature of team composition, assuming that each team member possesses only a single quality or skill that contributes to the teamwork (Huo et al. 2019; Harrison and Klein 2007).

In summary, even though there is a large body of research regarding the effects of the diversity of individuals’ attributes on team work functioning, the question of how to optimize the various personal qualities is less studied. This is for a good reason: the multitude and complexity of different qualities and actors in dynamic team work makes it very challenging to identify an optimum. While existing research tends to focus on relatively stable teams (Bell et al. 2018), the question of how the matchmakers deal with the optimization problem in the assembly of innovation teams remains understudied (Gryszkiewicz et al. 2016). Therefore, it is relevant to study experienced matchmakers’ perceptions regarding this question.

2.2 Information Technology Assisting Team Assembly

We subscribe to Salas et al. (2018) who call to “address issues with technology to make further improvements in team assessment.” They note together with Tebes and Thai (2018) that individuals should be involved in the research process to approach real-world problems and close the gap between theory and practice. In general, it seems that prior research on matchmaking for team assembly in workplace settings is limited—especially considering the context of innovation teams (Gryszkiewicz et al. 2016; Fecher et al. 2018) and generally the appropriateness of matchmakers’ computational tools (Cappelli 2019).

In HCI and CSCW, computer-aided team assembly approaches have been classified as follows Jahanbakhsh et al. (2017) and Harris et al. (2019): (i) Self-assembly, meaning it is up to individuals to select cooperators (might include computational guidance or advice); (ii) criteria-based, that is, matching is automated by algorithms and performed according to fit of the individuals’ qualities. A systematical review of the CSCW literature on team assembly (Harris et al. 2019) reveals that the majority of prior research on group assembly technology is focused on individual perspective where group membership comes with mobility and low cost. Recently, Gómez-Zará et al. (2020) proposed a taxonomy for existing team assembly systems based on user’s agency and participation. The two dimensions manifest in four types of teams: self-assembled teams (“users assemble their own teams on the system”), staffed teams (“the user establishes the team formation criteria on the system”), optimized teams (“the system assembles teams based on defined criteria and the user’s input”) and augmented teams (“the system augments users’ teammate choices”). For example, in staffed teams the user agency and participation are both high. Examples of such systems include TeamBuilder (Karduck 1994) and a sales team builder (Alkan et al. 2018). This article covers two important aspects that Harris et al. (2019) raised in their review: (i) how to deal with the imbalance of individual expertise in teams; (ii) how to consider the effects of technologies on team member attributes, group structures, task characteristics, and the context.

2.2.1 Self-assembly

Research in HCI and CSCW has focused on assembling teams online on digital platforms. For example, team assembly that happens in the context of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) or virtual environments for distributed collaboration (Wen et al. 2017; Walton et al. 2015). Interestingly, a variety of studies have been conducted on compositions and effectiveness in the context of eSports (Alharthi et al. 2018; Kim et al. 2017; Freeman and Wohn 2019). The context of eSports is an example where team assembly is typically based on self-selection. Players search for a suitable group based on available information that includes data on (i) instrumental qualities (the competence) and (ii) cues about social skills that would increase the likelihood of team success (Freeman and Wohn 2019).

Furthermore, the self-assembly approach has been utilized, for instance, by Lykourentzou et al. (2017) who introduced the team-dating technique for ad hoc team assembly. The users had short dates to evaluate other users and data could be later used to automatically create more effective teams. In a similar vein, custom-tailored chatbots have been proposed to elicit in-depth information about a team member’s personality in order to learn about individual preferences before teamwork (Xiao et al. 2019). Recent study on individual characteristics (Gómez-Zará et al. 2019) showed that especially bridging and bonding capital influences people in the selection of potential teammates, meaning that it is likely that an user invites someone that s/he is already familiar with.

2.2.2 Criteria-based Team Assembly

A variety of HCI research is focused on evaluation of existing criteria-based team assembly tools. For example, Jahanbakhsh et al. (2017) studied CATME – a Comprehensive Assessment for Team-Member Effectiveness, which can be used in university courses. The authors investigated perceived strengths and weaknesses of an automated team assembly tool from the perspectives of both the students and the instructors. The instructors were able to select a set of criteria based on what they believed were the most appropriate for their academic course (e.g., working style and demographics). They felt that the tool increased efficiency and leveled the playing field. Frequently a student’s interpretation of what criteria should have been used did not match with what the instructor ended up using. As an idea for improvement, instructors called for better guidelines for configuring the criteria and a possibility to engage students in selecting which criteria are used in the tool. Furthermore, Hastings et al. (2018) showed that multi-criteria configurations in CATME do not achieve stacked benefits.

In contrast to the prior research with a system evaluation approach, we are interested to take a more user-centric approach and understand the matchmakers’ team assembly practices and experiences. It seems that prior research has not been able to motivate the technology development with the matchmakers’ actual needs or practices. Instead, the research motivation often comes from a general observation that effective teamwork is ever more important and, therefore, new tools for optimizing the selection are worth pursuing. We argue that this approach does not sufficiently consider if and how the tool offers an appropriate support in matchmaking. The present study aims to provide insight into what kind of qualities or criteria are typically sought to further understand the matchmaking process and enable design of next-generation matchmaking tools.

3 Methodology

We conducted altogether 13 in-depth, face-to-face interviews of professionals who regularly assemble innovation teams. The interviews were semi-structured by nature, featuring a broad array of open-ended questions. Twelve interviews were conducted at the workplace of the participant and one at university facilities.

3.1 Participants and Recruitment

The participants were recruited from different institutions in Finland, which is the cultural environment that the authors are most familiar with. Relevant candidates were identified based on their online profiles, such as LinkedIn, and further invited via email. Some of the participants helped us to find more potential interviewees by recommending people they knew in other organizations (i.e., snowball sampling). As an extra incentive, each participant was granted two movie tickets (worth 30EUR) after the interview. One interview was conducted in English with a native English speaker (P2), while the rest were conducted in Finnish.

Eleven participants were matchmakers at private sector organizations that look for voluntary people (primarily but not exclusively Master students) to join multidisciplinary innovation projects. One of the participants was developing technology to support team assembly, and another served as a coach for managerial people who assemble and work with organizational teams. The context of the matchmakers’ work mainly relates to nationally well-known innovation platforms or innovation labs (Demola GlobalFootnote 1, Smart Campus Innovation Lab, SitraFootnote 2 and Y-KampusFootnote 3). The projects are generally set up to look for innovative solutions to loosely defined challenges, specified by local organizations in need of fresh ideas (Gryszkiewicz et al. 2016; Fecher et al. 2018). In practice, all the interviewees were involved in forming multidisciplinary and knowledge-intensive innovation teams.

In general, the participants have established a strong professional track record in relation to team assembly activities, as depicted in Table 1. The experience column refers to the number of years spent in the organization or around relevant activities or the number of projects the person has assembled. One participant did not disclose how much experience s/he had but it is safe to say that all the participants do the kind of work that is closely related to team assembly. A few of the participants were not actively assembling teams at the time of the interview yet they were still working closely with or for people who assemble teams on a regular basis.

Generally, assembling teams and related activities are key parts of the participants’ duties. Their typical tasks include project topic specification, attracting and gathering a pool of potential team members, and the comparison and selection of the applicants. In this sample, the target size of a team typically varies from four to eight people. The nature of innovation projects often calls for recruiting people with technical, design, and business skills and, importantly, domain knowledge about the project topic. Typically, several project teams are set up at the same time. The applicants can apply to one or more projects but the matchmakers would typically consider all applicants for all projects. The projects typically last from two to four months and are part-time engagements for the team members.

3.2 Data Gathering and Analysis

After filling in the consent form, the interviews started by asking about the participants’ activities related to team assembly and their experience in doing that. A central theme was their typical practices in team assembly. They were inquired, for instance, how the team assembly is predefined and what kind of criteria they use. To make the discussion well-grounded in real practices, we asked them to give concrete examples on typical team assembly processes. The interview structure also covered topics related to the information matchmakers use for matching, and how they obtain it. Other questions addressed how they assess the qualities of people and on what basis they match people together. The role of technology, the perceived challenges in the decision-making and subjective definition of a successful team or project were also addressed throughout the interview.

All the interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews conducted in Finnish were fully translated by the first author to English, however shortening some parts of the quotes for clarity and brevity. The average length of an interview was 74 minutes (min. 52 minutes and max. 113 minutes). With altogether 93,051 words of transcribed material, the interviews provided a rich textual data set that we analyzed using the Atlas.ti software. We employed a constructivist Grounded Theory oriented analysis. First, we recognized relevant team composition related themes and conducted initial open coding while reading through the data line-by-line. We then linked related themes producing large conceptual maps and networks of codes (i.e., axial coding). Finally, we used focused coding to synthesize data. We ended up with a set of codes with the most analytical power and organized them to our Findings. The coding was primarily conducted by the lead author using Atlas.ti, periodically being challenged and enriched by a senior scholar. The senior author participated in all stages of research except conducting and transcribing of the interviews. We organized meetings in every stage of the coding where we discussed individual codes, made clarifications to our categories and decided which would be the most interesting themes to report.

4 Findings

While conducting the interviews, it became quickly clear that the role of IT in the studied activity was rather minor, mainly confined to collecting the volunteering participants’ resumés and communicating with them. This observation consolidated our decision to focus on team assembly as decision-making in terms of social matching, regardless of the IT tools in use, rather than analyzing the use of very conventional tools like Microsoft Excel. We organize the results according to three main themes: team assembly as a decision-making practice, team composition including different approaches, and relevant individuals’ qualities in this type of teamwork.

4.1 Team Assembly Includes many Decision-Making Challenges

The participants perceived that a volunteer-based innovation project gives plenty of freedom in deciding who could work together, hence enabling collaboration also between people who normally would not collaborate. However, while most participants had pondered how to optimize the teams in different respects, in practice the selection process is naturally limited by the number of voluntary applicants. Also, the higher the freedom of choice is, the more challenging the comparison and decision-making becomes. Several participants recognized that they face challenges with the sheer amount of information that comes with the applications: one would ideally familiarize oneself with every application before making the final selection. At the same time, some matchmakers have to assemble the team from a small number of applicants and with straightforward selections without having time for a detailed comparison phase.

In addition to matching individuals with each other, also the project-applicant fit needs to be considered. The participants pointed out that they need to consider the applicants in relation to the project requirements from two perspectives. First, if it is practically possible, one considers the potential roles and responsibilities on the team-level. Second, one needs to match individuals’ qualities also with the project’s particularities. Typically, one would form an educated guess on what type of background or studies are needed in a particular case based on the topic of the project. At the same time, the participants were cautious not to fix an applicant to a certain role. Consequently, project-applicant fit is about balancing between making an educated guess in order to have predictability and giving participants room to surprise.

“I do think about roles at some point but I do not think like “s/he is probably going to be the project manager” [...] I do not want to think that this person is the one who develops the most unique ideas or this person is the one who is able to create the first lines of code.” (P13, speaking of a higher education innovation project)

4.1.1 Taking Risks to Reach an Unreachable Optimum

In order to maximize a team’s innovation potential, the matchmakers pointed out their willingness to take what they perceived as bold risks. P4 explained that he had changed his team assembly approach from tightly drawn criteria regarding fulfilment of key skills to making as ambitious combinations of people as possible. In practice, the ambition manifested as high diversity of educational backgrounds, ages and cultural backgrounds. In such cases, the participant mentioned to be aiming at enabling radical innovations rather than incremental innovations. By making seemingly surprising choices, so-called wild cards, they could optimize for high potential for novel solutions.

“I make quite a lot of provocative choices, so I dare to pick anything, provided that the team dynamics works and some very interesting avenues are opened. Even absurd combinations. This has almost turned to personal challenge seeking.” (P4, speaking of assembling teams for higher education innovation projects)

In a few interviews, the matchmakers highlighted that they get pleasure from making risky choices that turn out to yield great results. The riskiness referred to, for example, combining people that do not have substance skills relevant to the project topic or being unsure if the applicants are motivated enough. It is noteworthy that the nature of innovation projects allows taking risks and more freedom from the fear of making mistakes, when compared to other forms of matching, such as recruitment. The most experienced matchmakers said to have developed self-confidence that allows them to try new compositions and make quick selections based on intuition. In other words, the matchmakers try to balance between maximizing innovation potential and making overly ambitious, i.e., practically dysfunctional team compositions.

“There have been surprises. For example, in one case, we were a bit unsure of the motivation of a person. Would she shine or could she even quit at some point? We took a risk and selected her. She has proved to be marvellous regarding her attitude and is doing things with a big heart and enthusiasm.” (P12, speaking of selecting somebody to a higher education team)

There is no ultimate answer regarding the perfect team composition. The optimum was regarded as a moving, even unattainable goal. The ambiguity of an optimum in team compositions is also explained by the dynamics within an innovation project. For instance, the success of one team member might depend on whether another team member will succeed. Over the life-cycle of a project, the team members might have different responsibilities at different stages of the project, which also changes the criteria for the optimal composition. Overall, this ambiguity led to expert matchmakers being able to justify almost any team composition based on some criteria, as demonstrated by the quote below.

“You can assemble any kind of team and justify it by saying that it is what it is because of this and that [...] Basically we can make this type of decisions on any basis.” (P4, speaking of the uncertainty related to team assembly)

4.1.2 Matchmakers’ Awareness of their Selection Biases

Some rare occasions of matchmaking were said to be very straightforward, the matchmakers would use a score-sheet and give points to the applicants in different phases of the matching process. In this case, the phases typically include screening an application, face-to-face interviewing and group-based interviewing. The matchmaker gives points based on the perception of whether the applicant gives a positive or a negative impression at each phase. One participant pointed out that the key factor they try to spot in such situations is whether the applicants have negative attitudes or other potentially adverse factors on the team dynamics, that is, significant hindrances or barriers for the project success.

The straightforward approach to decision-making was, however, considered to come with the cost of biased decisions. Many matchmaking decisions and candidate evaluations were said to be largely based on intuition. The process resembles availability heuristics where sought features of people are recognized based on the matchmaker’s previous experience in working with teams that aim for innovation.

Many of the participants said to be able to scan a profile of a person without reading every piece of information. In other words, rather than using a strict criterion, they tend to lean on expert intuition. In many cases, a quick scan meant glancing through demographic information and the motivation letter, which were typically requested from the applicants. While it was noted that experience in matchmaking creates trust to confidently make quick decisions, it was also seen to render the decisions hard to justify rationally. Notably, and in contrast to other matching activities, assembling multidisciplinary innovation teams is characterized by the possibility and often by the necessity to make quick decisions.

Especially familiarity between the matchmaker and a potential applicant divided opinions. For example, applicants who have shared connections with the matchmaker might have an advantage in the matchmaking process. On the positive side, matchmakers look for people who they can trust to become valuable team members. Sometimes there is an opportunity to select people who are known to be accomplished team workers, based on being familiar with the persons. On the other hand, familiarity introduces a bias to the selection, hence the matchmakers were often consciously trying to avoid favoring or discriminating anyone.

“I have included someone in the team because I knew her/him only to be very disappointed by that [...] I try to put less weight on it (familiarity) than I have in the past [...] Every once in a while, they think: “oh, I know the instructor, I can just breeze through this.” (P2, pondering on including a familiar person to a higher education innovation project)

“Of course, I am a human and if I see that we have a mutual friend and I call her/him and ask how do you know her/him. What kind of a person is s/he? How did you meet?” (P7, speaking of the effect of having shared contacts)

4.2 Optimizing Team Composition in Practice

A recurring theme in the interviews was that there are various unpredictable and practical reasons why team members are unable to work well together. The practical reasons could include differences in language skills, challenges in matching schedules to work together, or physical distance between the team members. While such challenges are well known, it is hard for a matchmaker to prepare for them in the team assembly. On the other hand, matchmakers can have an influence on the team so that the members on average have the capabilities to complete the tasks. While some team members can contribute more than the others can, the matchmaker has to make sure that the work tasks can be balanced in a fair and meaningful way.

4.2.1 Principles in Relation to Heterogeneity

In most technology-oriented innovation projects, the matchmakers perceive that an optimal composition requires involving people from complementary fields or disciplines. The participants emphasized that while technical skills are very important, there should be enough diversity among team members, for instance, on the level of experience and values. Particularly, it was evident that there is a distinction between people who are capable of producing a prototype and people who are oriented towards producing user insight.

“If we start from having six people, I would like to have maybe four who really have some skills regarding technology [...] There needs to be... architecture skills or something that enables to design the thing [...] If there are only technical skills, it easily becomes like a job gig.” (P13, speaking of team composition in higher education innovation projects)

“Let us say that we launch two projects and in one we need strong engineer skills and in the other we definitely need social science students. Still, we want people from social sciences to the engineering projects and engineers or people with technology skills to social science projects.” (P3, speaking of diversifying higher education innovation projects)

Regarding an individual’s readiness to work in heterogeneous teams, one matchmaker was concerned that the team could lose some of its innovation capability if it includes a person who has previously only worked in teams with similar backgrounds of the members. The ability to work in heterogeneous teams was thus considered a skill to investigate in the team assembly. Furthermore, an interviewee who had worked in cross-organizational innovation projects reflected on the manifestation of diversity beyond demographic differences. For instance, multisectoral cooperation and bridging is important, i.e., the inclusion of both government and municipal stakeholders and the private sector. In addition, it is possible to increase diversity of viewpoints by including people from different organizational levels in a hierarchical organization. Variance in terms of expertise or experience also has potential to increase diversity. Overall, innovation projects were seen to allow bringing together people who would not otherwise meet due to hierarchy and lack of flexibility and cooperation between institutions.

“To be able to utilize multisectoral cooperation, you need people from governmental and municipal sectors [...] In addition of having different sectors represented, we try to find different people from the upper management, people from the middle management and workers.” (P9, speaking of multiorganizational innovation teams that focus on societal challenges)

4.2.2 Approaches in Team Assembly

The participants elaborated on different approaches to assemble a team by giving various examples. A common way is to build the team around one seemingly very suitable applicant. In the case of student-based innovation projects, the only requirement the matchmakers could identify for team assembly is to include one or two people who are knowledgeable about the project topic. In a typical case, applicants are added to the team one by one where each addition provides a new angle to the project topic or complementary value in relation to the already selected team members. Some matchmakers had the opportunity to use a computer software that enables drag-and-drop type of team building.

“The most common way is that we first check the whole list and if we find a gem that is a great match to the profile we are looking for, we take her/him and start to check other people around her/him. [...] In most cases, we start from a couple of people who have competence regarding the project topic or people who act as “glue” – meaning people who could work with anyone.” (P4, speaking of arranging approaches in higher education innovation teams)

“If a project has a technical aspect, (it is important to) make sure that there will be one or two people who can speak about it before making sure that the rest of the project team is filled.” (P2, speaking of arranging approaches in higher education innovation teams)

For the most of our participants, several teams would be assembled at once, to work in parallel during a predefined project period. Here, team assembly can be seen as a zero-sum game where it is necessary to consider whether to aim at several equally skillful teams or a few great ones. To this end, one approach is to aim for balanced and equally competent teams. In this case, matchmakers would continuously look for balance across the teams by using their judgment and various criteria. The participants described their thinking in typical matchmaking situations:

“I might (first) take all the business students, look at their motivations and distribute them across (groups), and then look at all the social sciences students and figure out how to distribute them. That way we could get well-rounded teams.” (P2, speaking of balancing higher education innovation teams)

“If we think from the viewpoint of the team, it might not be enough that you have every specialist of a certain topic in the same place. No, it is more about how they work together and how things like trust and empathy work... things that relate to the interaction, they are much more important than how smart they are or how good they are in their work.” (P5, a coach of team leaders and managers)

In contrast to the above-mentioned approaches, some matchmakers mentioned to have used an approach that could be considered the opposite, however less popular according to our data. That is, a matchmaker can prioritize some teams or projects over the others and create teams that have, in principle, higher potential to yield good results. However, the interaction among team members and the previously mentioned soft skills should still be considered.

“We also assemble teams that can be thought as, using interior design vocabulary... if we have six valuable pieces of furniture that cost 2000 per piece, they usually work together no matter what because they all are pieces of art. So (it is) a team of super people. Their communication might not be great as a team but they are able to produce something, because everyone is capable of doing something special.” (P4, speaking of assembling higher education innovation teams)

Along the same lines, some projects and team assembly cases might be given more effort or better tools, for instance, because the project partner pays extra. In other words, the business model of the innovation platform could also set priorities to the matchmaking process. Such mechanisms set the teams in unequal positions from day one, whereas a common value in education is to provide more equal opportunities across the population.

“When there is a student who would fit to every project, we have to think from the perspective of the client. If we have a client who has bought a package of four projects [...] compared to if we have a small company that is doing their first experimental project or has had the opportunity of a free project (with us). For the big, older clients, we prefer these “safe options” (people who are the most likely to succeed).” (P3, speaking of higher education innovation projects)

A risk for an approach where team dynamics are not that much in the focus is that the people might not be able to effectively work together. It is easy to agree on that in the short-term, there is no room for conflicts between team members. The interviewees pointed out that strong-minded people sometimes clash in teamwork. However, it was also noted that it is very challenging to identify such individuals or combinations in the selection phase. One way to identify determined people could be to check whether the applicant has been really active in the past.

“I personally think that it does not work if everyone is really eager and wants to be the leader. Moreover, if everyone is really determined, it does not work either. There needs to be a balance.” (P6, speaking of leadership qualities in higher education innovation projects)

4.3 Principles Regarding Individual Qualities

Identifying and describing one’s skills and strengths can be challenging for anyone, let alone students who are only building their professional identity. Hence, the applications often remain on a very general level, often not helping the matchmaker to consider the combinations. This also brings forward the challenges related to impression management and the role of the technology between the matchmaker and the applicant. Currently, electronic applications for the projects typically favor the applicants who are good at expressing their skills and qualities in written form. After all, other forms of communication, such as speech and video, are typically not supported.

“In theory, it is not even required to know what your [the applicant’s] skill levels are.[...] A skill can be very limited. The clearer and more concrete it is the better. It is a bit of an art form and it easily becomes nonsense. It is an advantage if the skill is potentially usable in other projects as well.” (P1, a CEO whose company is developing an app that matches people into teams within an organization)

4.3.1 Social Interaction Style Typically Matters the Most

When asked about the applicants’ most important qualities, many matchmakers highlighted the abilities related to communication and self-expression. All project members need to be ready for close-knit teamwork and brainstorming. Therefore, they need to be not only capable of discussing the project topic but also willing to share something about themselves in order to build trust. The team members are also expected to be able to provide constructive feedback to each other and give a chance for others to explain themselves. The ability to communicate was stressed especially in relation to the beginning of the project when the team needs to map out the current level of understanding in the team. However, and more importantly, such qualities were said to be very challenging to identify and compare based on the applicants’ resumés or even based on a group interview. According to the interviewees, focusing on the hard skills and motivation letters hinder making well-informed matching decisions but they had few ideas on how to mitigate this dilemma.

Regarding the working and interaction styles, the matchmakers reported a few differences that could be used to categorize individuals. For instance, an applicant might like to work on complex tasks that consider the big picture, while another prefers dividing the work into smaller and more concrete and attainable tasks. One might get excited by problem solving and brainstorming in the beginning of the project, while others might prefer grinding and doing more profound research. Matchmakers noted that the applicants differ in how much time they spend pondering, however, this might not predict success. Nevertheless, similar to the communication abilities, the matchmakers emphasized that they struggle to derive any insight on the way of working and interaction styles from the applications.

“For some, the grinding phase is very suitable but they would need something more for the beginning. If there is an unclear problem-solving task in the beginning, they might get frustrated. On the other hand, some people might be like “we will do this and that” and the others can continue from there.” (P10, a team coach who guides higher education teams)

“Some people quickly volunteer information [...] whereas others sit, ruminate about it for a bit, think about it and only after they get a concrete idea, they put it out like “should we do this?” and that is usually the best option.” (P2, speaking of individual differences regarding interaction styles in higher education innovation projects)

One matchmaker explained her thinking regarding the mismatch between the educational background of an applicant and the project topic. In such cases, there is typically some other reason, such as hobbyism, explaining why the applicant wants to join that specific project. Therefore, it is often perceived as a sign of creativity and courage if one applies for a project with which their skills or interests do not directly match. Especially if one is able to argue why their skills are relevant to the case, it indicates skills relevant to innovation projects.

“If a geo-engineer wants to look at software, I have no idea why. But if they really want to do it, there must be a reason. Let us find it out. To me that is fascinating, I love the notion of apparent misfits.” (P2, speaking of multidisciplinarity in higher education innovation projects)

4.3.2 Using Third-Party Tools to Model Behavior

During the interviews, the participants elaborated on using some third-party services to help their work. Particularly, the participants had mixed opinions about the so-called Belbin team role test (Belbin 2012). Measuring of personality or other individual qualities was seen as ethically questionable and potentially limiting a team member’s thinking about their role. If such tests are conducted, it is important to consider how the results are communicated and to whom. On the positive side, profiling personality could help to identify what would be an ideal environment for an individual, and the team role test could also be used to verbalize the differences within a team.

“We do not apply it [Belbin test], because the interpretation of the results is difficult and how can you tell the person the results in a way that it is useful and not harmful? Whatever measures you are using to classify people and put them into boxes, it easily becomes like “you are always like that” and “you are always in the corner”. Alternatively, people get behind it like “well, I am always like this, I do not have to learn.” (P5, a coach of team leaders and managers)

“I think Belbin is good, because it gives vocabulary to the students to talk about the differences, different ways to work in a team.” (P11, speaking of higher education innovation projects)

While the need for more detailed profiling of the applicants was evident, many participants felt that the matchmaking process should not be made too heavy by, for example, adding personality tests. This introduces an interesting contradiction and a need for making trade-offs between comprehensively analyzing the suitability of an applicant and keeping the application process light and the matchmakers’ decision-making practically manageable.

5 Discussion

This study asked how matchmakers experience the assembly of innovation teams as professional matchmaking and what kind of practices they have established for this activity. In sum, the interview study highlighted many considerations in this challenging matchmaking activity—ranging from alternative approaches to selection and team heterogeneity to various soft skills and selection biases—and indicated that IT indeed plays an insignificant role in it. The decision-making in selecting candidates to teams and thinking about the compositions seems to include much ambiguity, and it is hard to establish clear optimums to aim at. The matchmakers want to avoid biased decisions and try to make deliberate decisions, yet, at the same time, they also noted that rationalizing whether a decision was good or bad is very complex. While they were tempted to generalize their opinion based on the background or other attributes of the applicants, they might even overcompensate in fear of making biased selections. Furthermore, achieving optimal team composition was not seen as an attainable objective by the most of the matchmakers, at least with current tools and processes. As the projects are often loosely defined and the requirements for the outcome of the team-work are flexible, it seems relatively easy to find positive aspects and consider a project successful.

The context of innovation seems to condition matchmaking in different ways than other types of professional life matchmaking processes, such as recruiting or team assembly within an organization (Koivunen et al. 2019; Holm and Haahr 2019). For example, the interviewed matchmakers generally seemed less limited by predefined selection criteria or decision-making processes. Hence, they were able to try to maximize innovation potential by courageously composing diverse teams. At the same time, they tried to ensure the functionality of the team by including team members who seemed likely to quickly be able to work together, for example, by examining the educational backgrounds of applicants. The matching decisions on innovation platforms inherently face high levels of uncertainty that prevent completely unified and consistent approaches to team assembly. For example, it is hard to predict what kind of applicants will apply and, consequently, to foresee the possibilities for optimizing the compositions. Taken together, it seems that team assembly in this context has unique challenges, which implies that it is indeed meaningful to differentiate between different types of team assembly according to the context of operation and the purpose of the team.

Despite the apparent lack of suitable IT tools, the participants were generally optimistic that technology could have a bigger role and help partly automate and scale up the decision-making. IT could arguably support decision-making especially considering inexperienced matchmakers, also not forgetting the chance to reduce the amount of manual labor and cognitive load that is required especially when there are several teams to assemble at once. While the studied matchmakers used information technology relatively little, we recognize its potential in increasing objectivity in matchmaking, as will be further discussed later in this section.

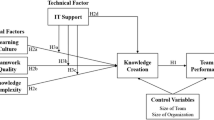

5.1 Tactics in Innovation Team Assembly

A specific opportunity that we identified for formalizing the qualitative findings relates to the different tactical approaches that the matchmakers had established over time. Even if not necessarily discussed explicitly, the participants seemed to stress certain mindsets or priorities when discussing how team assembly can be approached. As shown in Fig. 1, we identified different arranging and balancing approaches (here termed as tactics) that the matchmakers followed on three levels of decision-making. Mathieu et al. (2013) provide a good outline of the various team composition decisions, which we extend with empirical understanding of concrete tactical approaches in context of assembling innovation teams.

The levels refer to variance in terms of what entities the matchmaker is primarily considering and optimizing the compositions for: one individual, one team, or multiple teams to be working in the same organizational context. As our study implies that matchmakers often need to assemble multiple projects at the same time, the question of alternative tactics becomes particularly salient. This practice is common in the so-called innovation platforms with an open enrollment process where a matchmaker assigns or recruits people to teams from a large pool of people (Gryszkiewicz et al. 2016). Furthermore, the matchmakers often followed the so-called sequenced selection strategy (Mathieu et al. 2014). It seems that there is often a critical function in a team and matchmakers seek to fill that role first with a key skill person or a generalist. A person with substance knowledge about the topic of the project or one who can serve as social glue is a desirable candidate around whom to start building the team. After this, it was found common to try to find people with complementary skills in relation to the previous selection(s). In practice, this tends to become a sequential process where the matchmaker adds one person at a time to the team, typically considering the suitability of an applicant only in comparison to previous choices.

Arranging tactics

are typically present at the levels of selecting individuals and assembling a single team. Here, a matchmaker can start building a team by following the key-skill-first tactic, prioritizing individuals with key substance attributes, such as domain knowledge or crucial skills needed in the project, in the selection. The generalist-first tactic refers to selecting a teamwork player or social glue person who is, for example, likely to ensure effective teamwork due to their broad general knowledge. Finally, a matchmaker might prioritize applicants who have specified topics of interests that match the subject of the project (topic-interest-first tactic).

Balancing tactics

come into play when assembling multiple teams simultaneously. Equally-skilled teams tactic aims to balance the multiple teams regarding their chances of high performance and good group dynamics, spreading the available skills equally across all teams. This tactic was often present in contexts with educational motives, attempting to provide equal chances for the participants. In contrast, the high-expertise tactic is used for bringing together very talented individuals in few teams, thus ensuring that at least those teams will succeed in producing innovative outcomes for the project. This tactic seemed to be more common in contexts where multiple teams work on the same topic and the best outcome from several projects would be selected for follow-up work.

The importance of diversity was highlighted by all the interviewees and it is a salient theme in the data. However, a diversity-based approach did not seem to comprise a specific tactic in team assembly. Rather, diversity seems to be an overall perspective that affects the choices with all the tactics. For example, when a matchmaker is balancing the teams (in the case of equally-skilled-teams), they might consider diversity as one metric of equality. The findings provide support that it is important to consider functional heterogeneity in team assembly (Somech and Drach-Zahavy 2013). In addition to diversity regarding disciplines and functions, the participants emphasized that there should also be diversity regarding the level of experience and organizational level. At the same time, diversity is not usually a tactical starting point when considering arranging tactics but becomes evident when bringing applicants with a different profile to the team after the first selection(s).

All in all, understanding this variance of tactics helps to formalize different approaches to team assembly and, hence, to support them with IT applications, such as decision-support systems. Acknowledging the alternative tactics in the very design of digital tools opens an interesting design space of potentially very impactful IT, as further discussed in the next subsections. Additionally, we expect that further alternative tactics might emerge in the future as the use of cross-boundary innovation teams increases in various contexts. This study provides a solid starting point for further empirical research on matchmaking tactics in this regard.

5.2 Limitations

There are certain methodological limitations that limit the generalizability and applicability of the findings. First, the sample is limited to one country with a relatively homogeneous organizational culture and having several participants from one prominent organization that facilitates innovation projects. We encourage further empirical research in other cultural and organizational contexts. Second, as this study focuses on innovation teams, the findings might not generalize to other team assembly contexts. That said, we believe that the assembly of project teams in, for example, consultancies or production teams in creative industries could benefit from these findings. Third, because team assembly is still an emergent and relatively unestablished activity in many organizations, it might be affected by many aspects that this qualitative study failed to identify. We call for further research on not only other matchmakers’ experiences but also how the selected project members perceive the teams that have been assembled according to certain tactics.

5.3 Future Work and Design Considerations

In the light of this analysis, we argue that there is much room for introducing IT that helps matchmakers select more optimal team compositions. We call for courageous conceptualization of next-generation systems that could actively react to the matchmaker’s tactics, offer deeper insights into the candidate team members’ profiles, and offer interactive visualizations that help plan the team assembly as a whole. We plan to devise prototypes that manifest tactics or help the matchmaker to consider them. In particular, we believe that design efforts could focus on service features that assist matchmakers in multi-dimensional analyses of the individuals’ qualities and support comparison, as explained in the following list.

-

Enhancing user modeling. The decisions on team compositions are unavoidably influenced by the matchmaker’s understanding of the individuals’ qualities. Considering the breadth of potentially relevant qualities, likely many of them remain latent, that is, unacknowledged in the personal resumés and underutilized in matchmaking. Computationally assisting this issue necessitates more comprehensive and multi-dimensional user models. As current automatic profiling methods are typically intended to produce generally applicable representations of the actors (Sateli et al. 2017; Bastian et al. 2014; Horne et al. 2019), the models remain narrow in terms of ontological comprehensiveness. Hence, we call for new methods for deriving more nuanced insight about the applicants, for example based on the publicly available Big Social Data (Olshannikova et al. 2017) they have produced. This could mean traces of social interactions online, individuals’ participation in public discourses on topic of interests, or peer support activities in question-and-answer communities (e.g., Quora, Stack Overflow). While utilizing such data introduces dilemmas of data ethics and necessitates careful data management, it might also help to reduce the effects of intuition-based biases and to consider qualities that otherwise would remain unnoticed.

-

Offering interactive views to help team assembly on different levels. After the pool of applicants has been assembled, a view for each decision-making level (individual, single team and multiple teams) could support grasping a holistic picture of the team assembly complexity at hand as well as enable comparing teams. In the single team and the multiple team views, matchmakers should be able to see key information about qualities that they use to compare applicants (e.g., education, substance knowledge and skills) to further apply different prioritization tactics. Furthermore, the interface should allow the matchmaker to compare multiple applicants at once, place them effortlessly into teams, and contrast them with already selected team members;

-

Identifying potential team members. In the single team view, a system could highlight individuals with interest towards a particular project topic, people who match with the matchmaker’s preset preferences, and people who posses qualities that are significantly different in comparison to other applicants (e.g., a rare skill or rare education background) or a direct match to the project description requirements. While such features would allow quicker selection, they could also decrease the high cognitive load in cases where there is a large applicant pool and multiple teams to be assembled.

6 Conclusions

We interviewed 13 expert matchmakers who are regularly assembling multidisciplinary innovation teams, particularly in higher education. Based on a qualitative analysis of their experiences and practices, we found that the activity largely leans on personal decision-making and assessment, with digital tools playing an insignificant role. The selection of candidates to teams includes much ambiguity, and it was seen hard to establish clear optimums to aim at. According to the participants, the decision-making often features contradictions: wishing to avoid biased decisions and to make rational decisions but, on the other hand, also noting that judging the quality of a decision is complicated. As a highlight of the qualitative account, we identify and define three arranging tactics (“key-skills-first”, “generalist-first”, “topic-interest-first”) and two balancing tactics (“equally-skilled-teams” and “high-expertise-teams”) as alternative approaches to this complex activity. Based on the results, we discuss how IT could better support the decision-making process and call for more comprehensive user modeling methods. All in all, the study helps to design IT systems for decision-making based on different team assembly tactics.

References

Alharthi, S. A.; Raptis, G. E.; Katsini, C.; Dolgov, I.; Nacke, L. E.; and Toups, Z. O. (2018). Toward understanding the effects of cognitive styles on collaboration in multiplayer games. In: CSCW ’18. Companion of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing. New York: ACM, pp. 169–172.

Alkan, O.; Daly, E. M; and Vejsbjerg, I. (2018). Opportunity team builder for sales teams. In: 23rd International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, pp. 251–261.

Baker, B. (2015). The science of team science: An emerging field delves into the complexities of effective collaboration. BioScience, vol. 65, no. 7, pp. 639–644.

Bastian, M.; Hayes, M.; Vaughan, W.; Shah, S.; Skomoroch, P.; Kim, H.; Uryasev, S.; and Lloyd, C. (2014). Linkedin skills: Large-scale topic extraction and inference. In: RecSys ’14. Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Foster City, Silicon Valley. New York: ACM, pp. 1–8.

Belbin, RM. (2012). Team roles at work. Routledge.

Bell, S. T.; Brown, S. G.; Colaneri, A.; and Outland, N. (2018). Team composition and the abcs of teamwork. American Psychologist, vol. 73, no. 4, p. 349.

Cappelli, P. (2019). Your approach to hiring is all wrong. Harvard Business Review, vol. 97, no. 3, pp. 48–58.

Chatenier, E.d.; Verstegen, J. A. A. M.; Biemans, H. J. A.; Mulder, M.; and Omta, O. S. W. F. (2010). Identification of competencies for professionals in open innovation teams. R&d Management, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 271–280.

Chesbrough, H.; and Schwartz, K. (2007). Innovating business models with co-development partnerships. Research-Technology Management, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 55–59.

Edmondson, A. C.; and Harvey, J-F (2018). Cross-boundary teaming for innovation: Integrating research on teams and knowledge in organizations. Human Resource Management Review, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 347–360.

Fecher, F.; Winding, J.; Hutter, K.; and Füller, J (2018). Innovation labs from a participants’ perspective. Journal of business research, 110.

Freeman, G.; and Wohn, D. Y. (2019). Understanding esports team formation and coordination. Computer supported cooperative work (CSCW), vol. 28, no. 1-2, pp. 95–126.

Gómez-Zará, D.; DeChurch, L. A.; and Contractor, N. S. (2020). A taxonomy of team-assembly systems: Understanding how people use technologies to form teams. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, vol. 4, no. CSCW2, pp. 1–36.

Gómez-Zará, D.; Paras, M.; Twyman, M.; Lane, J. N.; DeChurch, L. A.; and Contractor, N. (2019). Who would you like to work with? use of individual characteristics and social networks in team formation systems. In: CHI’19. Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York: ACM, pp. 1–15.

Gryszkiewicz, L.; Lykourentzou, I.; and Toivonen, T. (2016). Innovation labs: leveraging openness for radical innovation? SSRN.

Hackman, J. R.; and Katz, N. (2010). Group behavior and performance.

Hall, K. L.; Vogel, A. L.; Huang, G. C.; Serrano, K. J.; Rice, E. L.; Tsakraklides, S. P.; and Fiore, S. M. (2018). The science of team science: A review of the empirical evidence and research gaps on collaboration in science. American Psychologist, vol. 73, no. 4, p. 532.

Harris, A. M.; Gómez-Zará, D.; DeChurch, L. A.; and Contractor, N. S. (2019). Joining together online: the trajectory of cscw scholarship on group formation. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, vol. 3, no. CSCW, pp. 1–27.

Harrison, D. A.; and Klein, K. J. (2007). What’s the difference? diversity constructs as separation, variety, or disparity in organizations. Academy of Management Review, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 1199–1228.

Hastings, E. M.; Jahanbakhsh, F.; Karahalios, K.; Marinov, D.; and Bailey, B. P. (2018). Structure or nurture? the effects of team-building activities and team composition on team outcomes. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, vol. 2, no. CSCW, pp. 1–21.

Haythorn, W. (1953). The influence of individual members on the characteristics of small groups. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, vol. 48, no. 2, p. 276.

Hollenbeck, J. R.; Beersma, B.; and Schouten, M. E. (2012). Beyond team types and taxonomies: A dimensional scaling conceptualization for team description. Academy of Management Review, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 82–106.

Holm, A. B.; and Haahr, L. (2019). E-recruitment and selection. In: E-hrm: Routledge.

Horne, BD.; Nevo, D.; and Adalundefined, S. (2019). Recognizing experts on social media: A heuristics-based approach. SIGMIS Database, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 66–84.

Hülsheger, U.R.; Anderson, N.; and Salgado, J. F. (2009). Team-level predictors of innovation at work: a comprehensive meta-analysis spanning three decades of research. Journal of Applied psychology, vol. 94, no. 5, p. 1128.

Huo, D.; Motohashi, K.; and Gong, H. (2019). Team diversity as dissimilarity and variety in organizational innovation. Research Policy, vol. 48, no. 6, pp. 1564–1572.

Jahanbakhsh, F.; Fu, W.-T.; Karahalios, K.; Marinov, D.; and Bailey, B. (2017). You want me to work with who? stakeholder perceptions of automated team formation in project-based courses. In: CHI ’17. Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Denver: ACM, pp. 3201–3212.

Jayne, M. E. A.; and Dipboye, R. L. (2004). Leveraging diversity to improve business performance: Research findings and recommendations for organizations. Human Resource Management, vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 409–424.

Johnsson, M. (2017). Creating high-performing innovation teams. Journal of Innovation Management, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 23–47.

Kale, A.; Kay, M.; and Hullman, J. (2019). Decision-making under uncertainty in research synthesis: Designing for the garden of forking paths. In: CHI ’19. Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York: ACM, pp. 1–14.

Karduck, A. (1994). Teambuilder: a cscw tool for identifying expertise and team formation. Computer Communications, vol. 17, no. 11, pp. 777–787.

Kim, Y. J.; Engel, D.; Woolley, A. W.; Lin, J.Y.-T.; McArthur, N.; and Malone, TW. (2017). What makes a strong team? using collective intelligence to predict team performance in league of legends. In: CSCW ’17. Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing. New York: ACM, pp. 2316–2329.

Koivunen, S.; Olsson, T.; Olshannikova, E.; and Lindberg, A. (2019). Understanding decision-making in recruitment: Opportunities and challenges for information technology. In: Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, Vol. 3. New York: ACM, pp. 1–22.

Kozlowski, S. W. J.; and Ilgen, D. R. (2006). Enhancing the effectiveness of work groups and teams. Psychological science in the public interest, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 77–124.

Levine, J. M.; and Moreland, R. L. (1990). Progress in small group research. Annual review of psychology, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 585–634.

Love, J. H.; and Roper, S. (2009). Organizing innovation: complementarities between cross-functional teams. Technovation, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 192–203.

Lykourentzou, I.; Kraut, RE.; and Dow, SP. (2017). Team dating leads to better online ad hoc collaborations. In: CSCW ’17. Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing. New York: ACM, pp. 2330–2343.

Mathieu, J. E.; Tannenbaum, S. I.; Donsbach, J. S.; and Alliger, G. M. (2013). Achieving optimal team composition for success. Developing and enhancing high-performance teams: Evidence-based practices and advice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mathieu, J. E.; Tannenbaum, S. I.; Donsbach, J. S.; and Alliger, G. M. (2014). A review and integration of team composition models: Moving toward a dynamic and temporal framework. Journal of Management, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 130–160.

Olshannikova, E.; Olsson, T.; Huhtamäki, J.; and Kärkkäinen, H. (2017). Conceptualizing big social data. Journal of Big Data, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 3.

Olsson, T.; Huhtamäki, J.; and Kärkkäinen, H. (2019). Directions for professional social matching systems. Communications of ACM. In press.

Richter, A. W.; Hirst, G.; Van Knippenberg, D.; and Baer, Markus (2012). Creative self-efficacy and individual creativity in team contexts: Cross-level interactions with team informational resources. Journal of applied psychology, vol. 97, no. 6, p. 1282.

Rowe, C.; Birnberg, J. G.; and Shields, M. D. (2008). Effects of organizational process change on responsibility accounting and managers’ revelations of private knowledge. Accounting, Organizations and Society, vol. 33, no. 2-3, pp. 164–198.

Sadler-Smith, E. (2016). what happens when you intuit?: Understanding human resource practitioners’ subjective experience of intuition through a novel linguistic method. Human Relations, vol. 69, no. 5, pp. 1069–1093.

Salas, E.; Fiore, S. M.; and Letsky, M. P. (2013). Theories of team cognition: Cross-disciplinary perspectives. Vol. 49. England: Routledge.

Salas, E.; Reyes, D. L.; and McDaniel, Susan H (2018). The science of teamwork: Progress, reflections, and the road ahead. American Psychologist, vol. 73, no. 4, p. 593.

Sankaran, S.; Vaagaasar, A. L.; and Bekker, M. C. (2019). Assignment of project team members to projects. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business.

Sateli, B.; Löffler, F.; König-Ries, B.; and Witte, R. (2017). Scholarlens: extracting competences from research publications for the automatic generation of semantic user profiles. PeerJ Computer Science, vol. 3, p. e121.

Somech, Ax; and Drach-Zahavy, A. (2013). Translating team creativity to innovation implementation: The role of team composition and climate for innovation. Journal of management, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 684–708.

Sun, H.; Teh, P-L; Ho, K.; and Lin, B. (2017). Team diversity, learning, and innovation: A mediation model. Journal of Computer Information Systems, vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 22–30.

Tebes, J. K.; and Thai, N. D. (2018). Interdisciplinary team science and the public: Steps toward a participatory team science. American Psychologist, vol. 73, no. 4, p. 549.

Terveen, L.; and McDonald, DW. (2005). Social matching: A framework and research agenda. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), vol. 12, no. 3, September 2005, pp. 401–434.

Tshetshema, C. T.; and Chan, K-Y (2020). A systematic literature review of the relationship between demographic diversity and innovation performance at team-level. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, vol. 32, no. 8, pp. 1–13.

Walton, J.; Bonner, D.; Walker, K.; Mater, S.; Dorneich, M.; Gilbert, S.; and West, R. (2015). The team multiple errands test: A platform to evaluate distributed teams. In: CSCW’15. Companion of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing. New York: ACM, pp. 247–250.

Weller, I.; Hymer, C. B.; Nyberg, A. J.; and Ebert, J. (2019). How matching creates value: Cogs and wheels for human capital resources research. Academy of Management Annals, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 188–214.