Abstract

One of the most significant legal acts concerning the sale and management of insurance risk was issued on January 20, 2016, based on Directive (EU) 2016/97 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 January 2016 on insurance distribution (IDD Directive). The adoption of European IDD principles aims to enhance transparency in the operations of insurance distributors and improve the standards of their business practices. Its protective scope encompasses all individuals and entities involved in the sale of insurance products. The aim of the article is to ascertain the regulatory authorities’ impact on the insurance market, consideration of consumer protection, in light of the changes introduced by the IDD directive. The primary entities under examination, in the mentioned context of consumer protection, are distributors and supervisory authorities. The discussion includes an overview of the scale of the insurance market and its fundamental applications, as well as compliance within the framework of behavioural economics theory. Additionally, the paper addresses the aspect of threats posed to consumers by the analyzed changes in the European insurance distribution market. In this segment, the authors concentrate on the economic and social ramifications of IDD implementation for entities operating within the insurance market. The concluding section outlines the potential for development and the future prospects of financial intermediation concerning IDD utilization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In response to disruptions in financial markets and notable disparities in insurance distribution across EU countries, the EU legislator opted for a closer harmonization of insurance mediation. These measures were prompted by the discrepancies observed in all markets, stemming from the absence of standardized qualifications for intermediaries and opaque compensation systems for insurance intermediaries (Gnath et al., 2019; Rustecki, 2017).

The reason why harmonization is such a crucial aspect of the insurance market, particularly concerning the distribution of insurance products to consumers,Footnote 1 is to guarantee a consistent level of protection across all Member States.

The EU legislator’s focus on insurance market stability is driven by a pragmatic approach influenced by two key factors. Firstly, the insurance market holds a significant position within the European UnionFootnote 2 (Insurance Europe, 2020), making any disruptions in such a crucial sector potentially causing economic disturbances across all EU member states. The second significant motive is the necessity to uphold consistent competitive conditions in the insurance sales sector across different countries.

Insurance mediation is closely intertwined with the operation and growth of the market. The intermediation process enhances the capabilities of market participants in capital accumulation within the economy, rejuvenates entrepreneurial activities, and promotes financial prudence in households. In the financial market, intermediaries assume a significant role as they are frequently regarded as experts in their respective domains. They possess a profound understanding of the market dynamics in which they operate and the risks associated with the transactions they facilitate (Focht et al., 2013).

A distinctive characteristic of insurance intermediaries is their direct interaction with the client (policyholder). Intermediaries frequently possess greater insight into the specific risks to which a client is exposed than the insurance company providing coverage for these risks. As such, intermediaries facilitate the flow of information. On one hand, they aid insurers in crafting innovative, competitive products, thereby fostering the growth of the insurance market. On the other hand, their actions, driven by information disclosure requirements, contribute to the advancement of society’s theoretical understanding of insurance, ultimately resulting in heightened insurance awareness (Cummins & Doherty, 2006).

The aim of the article is to ascertain the regulatory authorities’ impact on the insurance market, consideration of consumer protection, in light of the changes introduced by the IDD directive. The entities considered in the context of consumer protection include distributors and regulatory authorities. The discussion includes an overview of the scale of the insurance market and its fundamental applications, as well as compliance within the framework of behavioural economics theory.

The article presents the impact of the regulatory authorities on the insurance market in the light of the changes introduced by the IDD Directive in the Member States of the European Union. However, some of the descriptions, which extend the article with detailed solutions and comparisons, were characterized for only one country—Poland, and as far as the comparison of insurance markets is concerned, a comparison of the Polish market with the German market was presented. This choice was deliberate and results, among other things, from the impossibility of characterizing all EU countries in detail and the full availability of data from these two countries. In addition, these countries are characterized—in terms of the research carried out in this paper—by a significant number of insurance companies (second and thirteenth in the EU—Table 1) and a large population (Germany first in the EU, Poland fifth).

The Size of the Insurance Market and Its Institutional Environment

The institutional position of regulations in the insurance market should be considered in the context of European solutions (OECD, 2017). Supervision in the financial sector aims to ensure the following: (i) the stability of the financial system; (ii) the efficient functioning of financial markets; and (iii) that consumers are protected against bankruptcies or unacceptable conduct on the part of financial institutions. To achieve this, financial supervision is carried out by monitoring the behaviour of financial institutions, including compliance with rules and regulations (OECD, 2017).

The concept and mechanisms of any market can be defined both in macroeconomic and microeconomic terms. Following this logic, the insurance market, in macroeconomic terms, encompasses all exchange relationships among its participants. On the demand side, there are policyholders who transfer the risk associated with safeguarding personal and property rights in exchange for an agreed premium (the cost of insurance protection), whereas on the supply side, there are companies that are qualified to underwrite specific types of risk. The objective aspect on the demand side comprises the needs related to the insurance protection of personal or property rights. On the supply side, there are insurance products designed to fulfill these needs. The need for insurance is defined as a mental state of tension experienced by individuals or groups, stemming from a lack of certainty and guarantees concerning the preservation of life, health, property (physical security), or the assurance of psychological well-being (psychological security), and the desire to meet this need in the insurance market (Szromnik, 2001).

Insurance is therefore a distinct product within the financial market, with the insurance market being a component of it. It is a product characterized by bilateral information asymmetry, which refers to a situation where one party in a market has more information than the other, a fact which they can use for their benefit (Rybák, 2015). In the context of insurance, clients typically possess more knowledge about the subject of insurance than the insurer does. The insurance company may not have access to all the information regarding the risks it accepts for coverage. This situation can potentially lead to risk adverse selection, wherein only risks with a higher likelihood of loss are reported for insurance coverage. Consequently, insurers may need to increase premiums, which can result in reduced interest in obtaining specific types of insurance coverage. Information asymmetry on the client’s side can also give rise to the concept of moral hazard, which refers to reduced vigilance or care regarding the insured subject due to its insurance coverage. This behaviour may lead to increased insurance costs. In the context of information asymmetry, the insurance company typically possesses more extensive knowledge about its own operations and offers (Gallouj, 1997; Kurek, 2012). Due to the stronger position of the insurer, the role of the state and the supervisor is to limit the information advantage of the insurance company, as well as to take care of the market and minimize the customer’s advantage.

Hence, one of the primary objectives of the IDD Directive is to mitigate, by introducing the rule of acting in the “best interest” of the customer, the conflict of interest that often arises when intermediaries withhold crucial product information from consumers in pursuit of attractive commissions. Such a situation results in an evident conflict and exacerbates information asymmetry, particularly between well-informed intermediaries and less-informed consumers. At the same time new technologies are taking over insurance processes. According to Malinowska (2022), they can, fortunately, reduce the asymmetry of information. The introduction of new technologies means that the insurance company has more knowledge about the risk, which until now has mainly been the customer, the risk holder.

The Directive explicitly emphasizes in recitals (44) and (45) the necessity of guaranteeing a suitable level of consumer protection regarding the sale of insurance products that do not align with their needs. According to Marano (2021b) IDD pursues customer protection in two directions: protection at the point of sale and protection at the product design stage, both are influenced by the “Mifidisation” of EU insurance regulation.

When discussing the insurance market in Europe, it is crucial to highlight its diversity. These market differences encompass factors such as the number of companies operating in individual countries. For instance, France hosts 751 insurance companies, whereas Iceland has only 23. This variation across Europe arises not only from market size but also from its unique characteristics. In France, the significant number of insurance companies can be attributed to the market’s historical development and the prevalence of mutual insurance, with 369 such companies in 2020 alone—see Table 1Footnote 3 (Drees, 2022).

The insurance sector holds a pivotal position within the framework of a market economy. According to the European Commission, access to insurance products is a fundamental requirement for the proper functioning of modern society (European Commission, 2008). Several components of infrastructure exert a substantial influence on both the global insurance market and individual national markets (Sholoiko, 2017). Insurance companies serve the dual role of being significant financial intermediaries and substantial institutional investors. The financial activities of insurers fulfill a stabilizing function, benefiting both societies at large and the overall economy. Moreover, the insurance sector serves as a major source of employment in numerous countries (Arena, 2008; Bayar et al., 2021; Pradhan et al., 2017). Insurance, as a financial instrument, provides a mechanism for transferring risk from one party to another in exchange for the payment of a premium (Surminski & Thieken, 2017).

According to Insurance Europe, insurance plays a substantial role in driving economic growth and progress across Europe. European insurers disburse more than EUR 1,000 billion annually, equivalent to EUR 2.8 billion per day, in benefits and compensation. They provide employment to over 920,000 individuals and channel investments exceeding EUR 10.6 trillion (Insurance Europe, 2022a) into the economy. According to Insurance Europe (2022c), the European insurance market accounts for 32% of the worldwide gross written premiums. Nevertheless, in 2019, the average gross premium written per capita in Europe stood at EUR 2,187. In certain nations, the total insurance density surpassed EUR 5,000 per resident (Denmark, Luxembourg, and Switzerland). However, in Central and Eastern European countries, this metric still significantly deviates from the European average, despite more than doubling between 2004 and 2019. In 2019, the gross premium written per capita in this group of countries averaged EUR 339, with Slovenia reporting the highest insurance density (EUR 1,163 per capita), while Latvia (Laskowska, 2022) had the lowest (EUR 140 per capita). Table 2 provides an overview of the insurance market’s size in the European Union.

The indicated insurance sales in Europe encompass a range of distribution channels. The distribution models are influenced by multiple factors and exhibit substantial variations between countries, underscoring the diversity of insurance markets across Europe. For instance, life insurance in Europe is predominantly sold through bancassurance, with countries like Malta (79.8% of gross premium written), Portugal (77.9%), Italy (74.3%), France (64%), and Spain (59.2%) relying significantly on this distribution channel. Conversely, in the United Kingdom, life insurance products are primarily sold through brokers (69%), while in Bulgaria (82%), Germany (45%), and Poland (40%),Footnote 4 agents play a prominent role in selling life insurance products. In section II, agents play a dominant role in Italy (74.1%), Poland (62%), Luxembourg (58.6%), Portugal (56.8%), and Germany (58%). On the other hand, brokers have a significant share in property insurance, accounting for 68% in Bulgaria, 61.1% in Belgium, 50.1% in Great Britain, and 33% in Spain (Insurance Europe, 2022b). Other, previously unrecommended insurance distribution channels include employees of insurance companies and different insurance distribution channels (Rubio-Misas, 2022). Of particular importance and requiring regulatory attention are the “other channels” of insurance distribution, including online or telephone sales, fintechs—insurtechs (Sun et al., 2023), and entities that offer insurance distribution while selling their products, such as car showrooms or household appliance stores. The distribution of intermediaries across these various channels is detailed in Table 3.

Insurance intermediaries operating within the European insurance market are subject to various directives and regulations that govern their activities. The most significant legal provisions affecting their operations are summarized in Fig. 1.

List of legal provisions to which insurance intermediaries in the EU are subject.

Source: Own study based on The European Federation of Insurance Intermediaries (BIPAR), Insurance Intermediation, Brussels 2023,

Furthermore, in accordance with the aforementioned legal provisions, intermediaries are subject to oversight by various types of entities. Examples of institutions to which insurance distributors are accountable are illustrated using the Polish insurance market as an example (see Fig. 2).

To summarize, conducting distribution activities in accordance with legal regulations and guidelines of supervisory authorities means that an insurance distributor (in Poland):

-

− fulfills obligations arising from the provisions of, among others, the Insurance Distribution Act and the Personal Data Protection Act;

-

− protects themselves against possible customer claims (non-compliance of insurance with needs and expectations (ACS) as a basis for invalidating policies);

-

− provides a basis for avoiding penalties imposed by the Polish Financial Supervision Authority and the Personal Data Protection Office for non-compliance with the guidelines;

-

− by examining customer needs, they maximize sales opportunities (both current and future).

The regulation of insurance intermediation applies to the entire insurance market in Europe, which is not uniform. It is economically important for each country; and the interests of individual countries play an important role in establishing European insurance law.Footnote 5

The introduction of the IDD, aimed at protecting consumers, necessitated the establishment of a unified supervisory model in Europe, harmonization of national laws, with the possibility of retaining some differences but without granting them superiority. Consumer protection, (including control measures as detailed in the example of Poland—Fig. 2), aimed to be based on sound business practices rather than increased bureaucracy. One fundamental practice introduced by this Directive was mandatory professional training for distributors. European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) (Bernardino, 2015) played a crucial role in shaping the directive, which, based on the IDD Directive, established, e.g., the creation, public availability, and regular updating of a single electronic database containing information about all insurance and reinsurance intermediaries as well as ancillary insurance intermediaries that declared their intention to operate freely within the European market or provide services.

Behaviour of Insurance Market Entities in the Light of Behavioural Economics Theory

In economics, it is traditionally assumed that people make all decisions based on the concept of the so-called homo economicusFootnote 6 (Solek, 2010). The consequences of economic decisions are traditionally assessed solely in terms of the utility generated for the decision maker, without taking into account the situational context, emotions, or errors in information processing (Richter et al., 2019). However, the “average consumer” standard in force in the European Union contradicts the evidence presented in the field of behavioural economics (as discussed in this work). In reality, consumers in the insurance market are not always well-informed, prudent, and attentive. It is important to distinguish between the behaviour of the idealized European consumer and the actual behaviour of consumers (Mak, 2011; Sibony and Helleringer 2015).

The insurance market is a complex system characterized by various relationships between insurers and policyholders. The fundamental economic principle governing the operation of the insurance market is the law of supply and demand. On the other hand, the insurance market can be considered a special sphere of monetary relations, an insurance service (insurance protection), in which the sale and purchase of a specific product takes place, and the supply and demand for it is formed (Bekhzodovna, 2023).

The unpredictability of daily events and occurrences poses a significant challenge for accurate prediction and planning, as well as is the driving force behind people’s inclination to safeguard themselves against potential risks. In response to these risks, insurance companies provide products and services in the form of insurance policies, thus ensuring protection against a wide range of unforeseen events that have the potential to result in substantial losses. Customers select a specific insurer based on factors such as the quality of service, premium rates, coverage for claims, past interactions, and overall reputation (Blazheska & Ivanovski, 2021).

The central figure in economic and financial activities is the individual who makes decisions that influence the course of financial processes. These decisions are influenced by established normative goals as well as psychological aspects of decision-making. Recognizing the latter factors has paved the way for the emergence of behavioural finance.Footnote 7 Behavioural finance, which combines the tools of economics, psychology, and sociology in the analysis of the decision-making process, tends to significantly modify the expected utility theory. Behavioural finance encompasses a set of discoveries regarding simplified methods of comprehending the world (the so-called heuristics), as well as the errors individuals make in the assessment and decision-making processes. Participants in financial markets, including the insurance market, are susceptible to these biases and heuristics. Economic models developed within the realm of behavioural finance primarily aim to elucidate specific behaviours rather than solely focusing on prediction (Jedynak, 2022; Ricciardi & Simon, 2001; Sharma & Sarma, 2022). Therefore, behavioural economics explores how insights from the fields of finance, psychology, and sociology come together to enhance our comprehension of financial decision − making; what pitfalls and challenges individuals encounter when making financial choices; and how markets work or do not work as a result. The key distinction between mainstream economics and behavioural economics lies in their respective approaches to human rationality. The former in the concept of the economic man assumes that decisions are entirely rational. The latter, on the other hand, focuses on individuals who do not always make fully rational choices, with decision-making influenced by various social and emotional factors (Gorlewski, 2010; Kahneman, 2003).

The first work in this field, authored by P. Slovic (1972), was published in 1972. Research in this area has been and continues to be conducted by various scholars, including the following: R. Thaler (University of Chicago), W. de Bondt (University of Wisconsin), M. Statman and H. Shefrin (Santa Clara University), and D. Kahneman (University of Princeton).

Insurance is one of the most psychologically influenced financial products. It requires a specific mindset, a collection of traits, and certain beliefs to opt for it. Psychological research indicates that people’s decision to obtain insurance is not primarily driven by a pessimistic view of the future but by their overall life satisfaction and their capacity to plan for the future. Consequently, when deciding on insurance, rational choices are not always the sole guiding factors. The choice to buy insurance often coincides with unwarranted optimism and excessive self-assurance, which lead to an overestimation of personal experience and knowledge in the decision-making process (Czerwonka, 2015; Shefrin & Statman, 1993).

One of the paradigms of neoclassical economics is the pursuit of individual self-interest, which serves as the source of economic processes. The nature of these processes is tightly defined by a set of human characteristics, particularly their rationality in maximizing utility. Even T. Veblen and W.C. Mitchell highlighted the importance of habits, customs, and the consequences of information scarcity in decision-making (Mitchell & Veblen, 2022). Meanwhile, H. Simon (1955) emphasized the significance of the time factor, indicating that rationality requires unimaginably high predictive abilities, necessitating infinitely long periods of reflection.

In his works, H. Simon continually attempted to relate his considerations to the real world. He concluded that the most appropriate approach to rationality would be the assumption of “bounded rationality,” which takes into account the limitations of the human brain in processing information. Based on bounded rationality, it is considered irrational to be fully rational, as assumed by neoclassical theory. This led to the development of the “satisficing model” of the company, in which profit maximization was not the primary goal. Instead, the company determined profit margins and sales volume (Simon 1976). Criticism of neoclassical economics paved the way for the development of behavioural finance. Today, criticism is directed at the neoclassical notion of rationality, particularly the assumptions of free will, conscious choice, freedom, and the existence of consistent and ordered preferences. It is argued that the influence of habitual behaviours, impulses, curiosity-driven behaviours, and the tendency to forget is so significant that the existence of preference sets with model-like characteristics is practically impossible.

In 1979, D. Kahneman and A. Tversky proposed a model that also incorporated economic behaviours, which was named the prospect theory. This theory became a fundamental cornerstone of behavioural economics (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). The authors of the model address decision-making under conditions of risk (prospect theory) and suggest that people prefer a smaller but certain gain over taking risks (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Levy, 1992). For this reason, people often refrain from purchasing insurance as they tend to evaluate potential gains as lower than the loss incurred by paying the premium today.Footnote 8 In the context of behavioural economics, decisions regarding insurance are influenced by a phenomenon known as overconfidence bias (Sandroni & Squintani, 2004). The IDD aims to address this imperfection, especially in the analysis of customer needs. Due to the illusion of control and theoretical influence on external events, people estimate the probability of success above the objective probability. They believe that they can also control independent events (Langer, 1975). Overconfidence bias is associated with over-optimism, where individuals expect events to be better than they may actually turn out to be (Coats & Bajtelsmit, 2021). This can lead to refraining from purchasing insurance, assigning low probabilities to certain events, or considering them impossible (Kunreuther & Pauly, 2004).

Building on the prospect theory presented, Brighetti et al. demonstrated that it is primarily emotional and psychological variables that influence consumers’ insurance decisions (Brighetti et al., 2014). Furthermore, Kunreuther et al. showed that these decisions deviate significantly from fully rational behaviour (Kunreuther et al., 2013a). This is due to the emotions experienced by buyers because the motivation to purchase insurance is typically driven by fear, regret, and loss aversion (Schwarcz 2010; Zawadzki 2018).

Two important conclusions follow from the theory of perspective by Tversky & Kahneman (1992):

-

− firstly, we experience the value of a given thing by comparing it with other things;

-

− secondly, we are more sensitive to loss than to gain.

Prospect theory can be applied to decisions made regarding the purchase of insurance, namely (Kunreutheret al. 2013a, b; Laury et al., 2009):

-

− profits and losses of the same absolute value do not provide identical absolute utility. The discomfort of a loss is generally more severe than the utility of a gain of the same size.

-

− when purchasing insurance policies, we exhibit risk aversion (certain small loss), while the probability of an unfortunate event occurring is actually small (uncertain large loss).

-

− when making decisions about insurance, we tend to underestimate medium and high probabilities, but we overestimate low probabilities.

-

− willingness to take out insurance may be significantly influenced by how the information persuading people to take out insurance is formulated, either in terms of potential profits or potential losses.

Making decisions about insurance involves a choice between potential gains and potential losses, each with varying probabilities (Forlicz & Rólczyński, 2018; Harrison & Ng, 2016):

-

A.

I will not spend money on insurance (profit), but I may lose money due to misfortune (loss).

-

B.

Maybe I will not spend money on insurance (unnecessarily loss), but in case of a disaster I will receive compensation (profit).

In turn, the factors shaping decisions about purchasing insurance can be divided into (Browne & Hoyt, 2000; Tyszka & Zaleśkiewicz, 2001):

-

− the actual probability of the given event occurring;

-

− an individual’s personal perception or belief in that probability;

-

− the desire for total peace of mind, regardless of the actual probability of events.

To summarize, prominent researchers in behavioural economics and finance, D. Kahneman and A. Tversky, argue that we are more responsive to “in minus” than “in plus” changes. When deciding to purchase insurance, logical analysis of the situation or the perceived probability of an event may not be as influential as the emotions associated with that event (such as the experience of a flood or a traffic accident). Therefore, it is essential to consider the behavioural approach to insurance matters in the insurance industry.

The psychological challenge with insurance products is that the benefit of spending money on them is not immediately tangible but rather abstract, since we purchase insurance to cover potential costs in the event of an accident or unforeseen event. This situation presents a paradox. On one hand, we hope that nothing bad will happen to us, yet the money spent on premiums seems wasted. On the other hand, if an unfortunate event occurs, we receive compensation, which is satisfying, but it is challenging to find happiness in the midst of misfortune. In the realm of research conducted by Hogarth and Kunreuther (1989), noteworthy findings include:

-

− in his research, he demonstrated that when making insurance decisions, people tend to be more influenced by the probability of a loss rather than its magnitude.

-

− given the choice between insuring themselves against a larger but less probable loss or a much smaller but much more probable loss, people tend to choose protection against the latter event.

The framing effect (Graminha & Afonso, 2022) is indeed significant in risk-related decision-making. It pertains to the influence that the presentation or framing of a decision-making problem can have on the choices individuals make. Depending on whether the problem is framed to emphasize potential gains or potential losses, decision-makers may make significantly different choices (Jedynak, 2022; Richter et al., 2019). Even a minor alteration in how a problem is presented can result in distinct behaviour from the decision-maker. This phenomenon, known as the framing effect or framing, involves highlighting specific information, causing the recipient to concentrate on that particular facet of the issue (Zielonka, 2017). Framing plays a pivotal role in how insurance products are presented by insurance advisors or in informational brochures (Brown et al., 2008, 2013; Goedde-Menke et al., 2014). This is connected to the level of insurance knowledge within society. Understanding the factors that influence insurance knowledge is crucial for insurance companies, regulators, and policymakers aiming to enhance insurance coverage in a specific countryFootnote 9 (Kadoya et al., 2022). According to social learning theory, individuals acquire knowledge through social interactions and often mirror what they learn in their financial behaviours (Scavarelli et al., 2021). Consequently, environmental influences stemming from family, peers, educational institutions, and the media are anticipated to mold people’s financial knowledge (Gutter et al., 2010; Lee & Lee, 2018).

In turn, P. Slovic (1987, 1992) distinguished three qualitative dimensions of risk assessment related to:

-

− level of (lack of) knowledge of the phenomenon;

-

− level of anxiety arousal;

-

− number of people exposed to danger.

Each of these dimensions can lead to different perceptions of the risk associated with a particular event (regardless of its objective probability) and, consequently, varying levels of willingness to purchase insurance. The first factor, which is unknown risks, pertains to the risk linked with new, unusual, unfamiliar, or challenging-to-define situations (e.g., an unknown disease). This factor has limited influence on the inclination to buy insurance. Firstly, such events are often not well-defined, and secondly, insurance companies typically do not offer coverage for such abstract occurrences. The second factor, which is the level of anxiety, relates to the connection between negative emotions and the assessment of a specific situation. Undoubtedly, this factor significantly impacts the willingness to acquire insurance. The third factor, i.e., the number of individuals exposed to the same danger simultaneously, also contributes to perceiving a situation as riskier and more likely. Frequently, the subjective dimension of risk perception is not aligned with the objective likelihood of an event occurring (Slovic 1987, 1992).

The anchoring effect refers to the influence of a specific, arbitrarily chosen, and often unrelated initial value (anchor) on the estimation of a particular parameter or quantity (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). The certainty effect is also relevant in financial decision-making. It involves individuals giving more weight to events they perceive as more likely (Graminha & Afonso, 2022), while attaching less significance to the severity or magnitude of those events.

The factors mentioned above are relevant to insurance decisions that are closely tied to knowledge about insurance. Driver et al. (2017) discovered that insurance illiteracy results from factors such as limited product knowledge, low trust in insurance providers, insufficient awareness of risk mitigation strategies, and cognitive biases in decision-making. It is worth highlighting the groundbreaking work by Bristow and Tennyson, who defined insurance literacy as an individual’s capacity to comprehend insurance principles and the characteristics of insurance contracts (Bristow & Tennyson, 2001). Consequently, a lack of insurance knowledge leads to individuals not recognizing the importance of having insurance coverage and, as a result, being underinsured (Driver et al., 2017; Weedige et al., 2019).

Finally, it can be emphasized that one more variable influences the implementation of the provisions of the IDD Directive. Decisions made on the financial market also result from the gender of the decision-maker. Women tend to be less confident (Sarsons & Xu, 2021). In theory, this can protect them from making irresponsible—overly risky—decisions on the financial market, but it can also prevent them from fully utilizing their financial knowledge (Yeh & Ling, 2022). Furthermore, according to Lusardi and Mitchell, “Women uniformly know less, and they know they know less, than do men, in terms of financial knowledge” (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2011). However, it is important to note that knowledge or sex alone cannot be conclusively associated with a specific approach to risk, since among low knowledge individuals, men are more risk or ambiguity prone, among high knowledge individuals, women are more risk or ambiguity prone (Gysler et al., 2002).

Changes in the European Insurance Distribution Market

As indicated, the insurance sector is undergoing unprecedented changes. Insurers are constantly contemplating how the market may respond to alterations in the insurance distribution model (Svoboda, 2021), in the context of the implemented the IDD Directive.

The EIOPA report analyzes the impact of the IDD in three main areas (EIOPA, 2022):

-

I.

Changes in the EU insurance distribution market.

-

II.

Impact of the new regulatory framework.

-

III.

Impact of the new supervisory framework.

The report highlights that in the European Union, the number of intermediaries notably declined between 2016 and 2020. It also observes that bancassurance had a substantial role in the distribution of life insurance, whereas other intermediaries primarily dealt with non-life insurance contracts. Additionally, EIOPA noted a consistent increase in online sales, a trend that was further accelerated by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The insurance distribution market is undergoing constant changes. They became especially evident following the introduction of the IDD Directive (further details on this can be found in other sections of this work), but also during the COVID period, when the digital transformation of the economy accelerated. Then, the insurance market had to adapt to the change in the insurance distribution model. First of all, it was necessary to urgently adapt, often, new technical possibilities, which were then successively implemented (Eckert et al., 2021; Hinrichs & Bundtzen, 2021). Digitization and remote sales, which were sometimes challenging to implement prior to COVID-19, quickly became the standard, reshaping the market rapidly. These changes represent a unique opportunity for insurers to gain a competitive edge but also present challenges in meeting the obligations stipulated by the IDD Directive (Pauch & Bera, 2022). Insurers must ensure their clients’ financial security and provide them with appropriate insurance coverage (Howells, 2020; Levantesi & Piscopo, 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic also changed the insurance market due to a significant reduction in people’s income. Interest in private health insurance increased. However, while the demand for this insurance increased in Poland (PIU, 2022), it decreased in the USA, probably due to lower incomes of the population (Trinh et al., 2023).

Impact of the New Regulatory Framework

EIOPA claims that some industry associations have reported a positive impact of the IDD on the distribution of insurance among consumers, citing a reduction in the number of customer complaints. Consumer associations, however, have particularly highlighted problematic practices related to the sale of life insurance linked to investment funds and insurance coverage accompanying mortgage and consumer loans.

The report noted that attention should be paid to cases of lack of training for insurance distributors, especially concerning certain types of investment insurance products that are not easily understandable for consumers.

EIOPA has also identified two areas where the full potential of digitization and new distribution models could not be fully realized in the last three years. Legal frameworks are insufficiently adapted to digital changes and do not adequately address the opportunities and threats posed by digital platforms and artificial intelligence.

However, the Directive does not provide exact regulatory frameworks, and for this reason, the legislations of individual countries may not guarantee full and consistent consumer protection. In the case of Poland, this diversity is confirmed by the Supreme Audit Office (NIK), which, in its assessment, emphasized that the entities controlled in terms of distribution did not create formalized comprehensive rules for monitoring unfair practices that violate consumer interests in the insurance market. Additionally, the institutions responsible for consumer protection did not cooperate sufficiently among themselves (NIK, 2019).

Impact of the New Supervisory Framework

EIOPA has stated that the level of resources allocated to supervising economic activities increased moderately between 2018 and 2021. Nevertheless, EIOPA’s supervisory work has shown that not all relevant national authorities have sufficient tools for effective oversight of insurance activities. Several relevant national authorities have indicated that they would like to adopt actions such as “mystery shopper.” According to information provided by the relevant national authorities, the most common supervisory tools used by them to monitor the implementation of the Insurance Distribution Directive are on-site inspections and external monitoring.

The IDD is just one element of the puzzle in creating a single insurance market in the EU. If a single insurance market in the EU is to become a reality, many more elements need to be implemented. As expected, some stakeholders have addressed persistent obstacles to insurance intermediation, including the lack of harmonized European insurance contract law, social insurance law, and tax law. EIOPA is expected to propose changes when it publishes its next review in early 2024.

Proper management of distribution risks prevents harmful behaviours towards clients who are exposed to potential harm resulting from the distribution of poorly designed or inadequately distributed insurance products. Therefore, clients would also benefit from proper risk management associated with distribution, in which both insurers and distributors are subject to the same principles and supervision (Marano, 2021a).

However, despite having a single insurance distribution directive, the European insurance intermediary market exhibits significant diversity in local distribution channels and varying national definitions. Practices related to registration and reporting also differ among individual member states, contributing to the diversity of the European insurance intermediary market (EIOPA, 2018).

As a result, the IDD Directive was designed to provide equal protection to insurance customers, regardless of the type of distributor from whom they purchased insurance (Martinez & Marano, 2020). The Directive aims to enhance the protection of customers and retail investors buying insurance products or insurance-based investment products (Noussia, 2021).

The main principles of the IDD Directive regarding insurance intermediaries are as follows (BIPAR, 2023):

-

− the requirement to be registered and supervised by the competent supervisory authority;

-

− possessing the necessary knowledge and skills and undergoing regular training to enable professional development (Continuing Professional Development—CPD);

-

− having a good reputation;

-

− having liability insurance related to the exercise of the insurance intermediary profession;

-

− Having measures to protect customers against inability to transfer the premium /amount of claim or return premium to the insured;

-

− acting honestly, fairly, and professionally, in the best interests of clients;

-

− prohibition on receiving any remuneration that conflicts with the duty to act in the best interests of clients;

-

− disclosing the nature and basis of the remuneration received;

-

− detailed requirements for product oversight and governance (POG).

According to data obtained by EIOPA, only 25 competent national authorities provided information on the number of registered insurance intermediaries in the years 2016–2020.Footnote 10 Based on data from these 25 competent national authorities, there were 815,219 registered insurance intermediaries on those markets (as of the end of 2020).Footnote 11 As for the trend in the number of registered intermediaries, the trend line shown in Fig. 3 indicates that the total number of registered insurance intermediaries significantly declined in the years 2016–2020, which has been a consistent trend for several years (EIOPA, 2018).

Source: EIOPA, Report on the application of the IDD, p. 16. https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/system/files/2022-01/eiopa-bos-21-581_report_on_the_application_of_the_idd.pdf

Number of registered intermediaries in the years 2016–2020.

Some competent national authorities provided explanations for the decrease in the number of insurance intermediaries. For example, Belgium emphasized that the main reasons for intermediaries discontinuing their activities are consolidation in the sector, the aging of intermediaries, and the reorganization of distribution models. The Czech National Bank and the Portuguese ASF indicated that the decrease in the number of insurance intermediaries could be attributed to additional requirements included in national regulations transposing the IDD—such as stricter professional requirements (EIOPA, 2022).

Additionally, among the factors that may contribute to the decreasing number of insurance intermediaries, there can be identified (EIOPA, 2022):

-

− decreasing profit margins, associated with increased competition;

-

− rising compliance costs, leading to the displacement of weaker intermediaries and raising the entry threshold for new ones;

-

− the aging of intermediaries, with many in the EU countries being around 50 years old. This means that they will retire within 15 years;

-

− the intermediary profession is becoming increasingly complex and demanding, which is also reflected in the IDD.

The IDD Directive (similarly to its predecessor, the Insurance Mediation Directive) does not provide definitions for various types of insurance intermediaries, such as agents, sub-agents, insurance agents, brokers, and bancassurance operators. Instead, it adopts an approach based on the form of insurance sales activities.

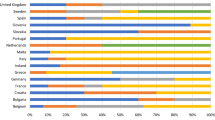

To promote greater data comparability, EIOPA has gathered information on the number of registered insurance intermediaries acting on behalf of—see Fig. 4 (EIOPA, 2022):

-

1.

One or more undertakingsFootnote 12;

-

2.

One or more undertakingsFootnote 13;

-

3.

Customer.

Source: Own study based on EIOPA, Report on the application of the IDD, p. 19. https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/system/files/2022-01/eiopa-bos-21-581_report_on_the_application_of_the_idd.pdf

Evolution of registered insurance intermediaries acting on behalf of different entities (one or more companies; one or more insurance intermediaries; customer) in 2020.

According to EIOPA’s data, only 19 competent national authorities were able to provide relevant data. From the information obtained, it can be inferred that in 2020, in 13 out of 19 Member States, the majority of insurance intermediaries operated on behalf of at least one insurance company. It is worth noting that in IE, IS, and LT, intermediaries operated only on behalf of one or a few insurance companies. In CZ, IT, and SK, on the other hand, most insurance intermediaries operated on behalf of one or a larger number of intermediaries. Intermediaries operating on behalf of clients were particularly numerous in FR, LI, and NO. The chart should be interpreted with caution because there are limitations regarding the quality of data and the level of comparability between Member States.Footnote 14

It should also be noted that the introduction of the IDD Directive has positive and negative aspects. The introduction of the obligation to conduct an analysis of customer needs should be considered positive, as it should support the professionalization of insurance distribution activities and a more thoughtful offer of insurance products by distributors. However, the negative aspect of introducing the obligation to analyze customer needs will be the risk of customers filing claims against insurance distributors more often for compensation for improper performance of distribution activities. Therefore, the European insurance distribution market faces a major challenge to meet the requirements of the IDD Directive and not be exposed to claims.

Economic and Social Effects of the IDD Directive on Insurance Market Entities

The paper will present research initiated by the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) in November 2020 regarding the implementation of the Insurance Distribution Directive (IDD). The survey-based research aimed to gather stakeholders’ opinions on their experience with the IDD, particularly concerning the improvement of advisory quality, sales methods, the impact of the IDD on small and medium-sized enterprises, and potential further enhancements identified after the application of the IDD. Stakeholders were requested to provide their feedback by February 1, 2021. EIOPA received responses from 128 entities in 16 member states. The respondents mainly included insurance intermediaries, insurance companies, and industry and consumer associations (EIOPA, 2020).

For a detailed analysis of the results obtained by EIOPA, the number of analyzed entities in this study was reduced from 128 to 70Footnote 15 to ensure that no country is overrepresented (in the case of Italy, out of the 78 entities surveyed, 22 were retained, primarily removing small entities, often individual agents). Next, the respondents were divided into two categories of insurance market entities: those representing the interests of clients (consumer organizations) and those representing insurance companies (insurance intermediaries, insurers). Another issue was the proper analysis of the responses obtained by EIOPA. The survey questions were both closed and open-ended. In the case of open-ended questions, the surveyed entities provided spontaneous responses without predefined options. To conduct an econometric analysis, the obtained information was categorized based on the nature of the responses. Table 4 shows the number of entities confirming specific responses regarding the IDD.

Beginning the analysis of the results regarding open-ended questions, it is worth presenting the comments provided by the respondents, which were used for the categorization presented in Table 4. These comments indicate various opinions regarding the impact of the IDD directive on the insurance distribution market, which, as stated throughout the entire study, cannot be solely assessed as positive or negative. Table 5 presents the actual comments from the survey respondents. It should be noted that these are subjective responses from the surveyed entities.

When asked: “Indicate by ticking “Yes” or “No” whether, in your view, the demands and needs concept is well functioning being mandatory for all distribution models in relation to non-advised sales of any insurance product.”, a certain pattern emerges. Among representatives of the supply side, the assessment of the functioning of the needs survey has a 50% positive and 50% negative assessment, while among customer representatives, negative assessments are more prevalent (Table 6).

To analyze the impact of the respondent’s form (entity representing the client or insurer) on the assessment of the implementation of the IDD Directive in the EIOPA study (presented in Table 4), the chi-square test of independence (χ2 test) was employed. In each instance, this form was compared with the IDDFootnote 16 assessments (the relevant calculations were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0).

For each pair of features, the null hypothesis H0 was established, assuming that the compared features are independent, while the alternative hypothesis H1 assumed that these features are dependent. If the calculated χ2 was greater than the critical value χ(df,α)2 (for degrees of freedom df: (r-1) (s-1) and the assumed level of significance α = 0.10), then H0 was rejected; otherwise, rejection of the null hypothesis was not justified. In other words, if χ2 ≥ χ(df,α)2, H0 was rejected at the α significance level, indicating that the features are dependent. If χ2 < χ(df,α)2, there were no grounds to reject H0, suggesting that the characteristics are independent (Krupa & Walczak, 2016). The description of the individual variables examined in the study is presented in Table 7.

The presented results indicate that statistically significant differences in responses only occur in the case of assessing the negative impact of the IDD on the market. Among customer representatives, as many as 42% evaluate the IDD negatively (5 out of 12), while insurance companies account for 19% (11 out of 59) of negative evaluations. It is essential to understand why this is the case, especially considering that the IDD was intended to benefit customers. To explore this further, it is worth examining some quotes from customer representatives:

-

− the “customer needs assessment questionnaire” is signed at the time of purchase and is therefore useless;

-

− some sales methods have deteriorated;

-

− low quality of sales, the sale is burdened with countless amounts of pre-contractual documentation that the customer does not read because it is too complicated.

Summarizing the research conducted by EIOPA, it can be concluded that a majority of the surveyed entities have expressed that the IDD generally had a positive impact on insurance distribution methods. However, comprehensively evaluating the effects of the IDD on consumers, insurance distributors, and regulators presents challenges. These limitations encompass:

-

− delays in introducing the principles of applying the IDD into the legal order in some countries;

-

− impact of the COVID-19 pandemic;

-

− regulations already in force in some countries regarding consumer protection on the insurance market (before the implementation of the IDD into national law).

As an element of the analysis regarding the IDD’s impact on the insurance distribution market, EIOPA conducted a study on the supervisory tools employed by regulatory authorities within specific countries to oversee the implementation of the IDD guidelines by insurance companies and distributors (EIOPA, 2022). EIOPA asked the relevant national supervisory authorities to rate the frequency of usage for various supervisory tools on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 = the least common usage; 5 = the most common usage). Based on the responses received from 30 national competent authorities, the research outcomes are presented in Table 8.

The results obtained enable to identify the two most commonly employed tools by supervisory authorities: on-site inspections (an average score of 4.0 for insurance companies and 3.9 for insurance companies/intermediaries), as well as external inspections (average score of 4.3 for insurance companies and 3.9 for insurance intermediaries).

Additionally, as part of other supervisory activities, the controlling institutions indicated (EIOPA, 2022):

-

− Registration of insurance intermediaries, including assessment of fitness and probity, professional knowledge and good repute—however, the degrees and depth of such activities differ with some NCAs assessing customer-centricity-mindset and others assessing simply the lack of prior criminal records;

-

− Approval of training providers for continuous education and compliance officers;

-

− Market research, including market trends analysis and market surveys – this even though consumer research to ensure outcome-focused supervision is limited;

-

− Cooperation with NCAs, including forward-looking supervision with home NCAs and technical pane;

-

− Analysis of the insurance undertakings’ periodic reports on the monitoring of the sales network and their received complaints;

-

− Analysis of the outcome emerging from the Retail Risks Indicators tool, based on the information flows provided by EIOPA for EU undertakings; and

-

− Life and non-life insurance products analysis.

Factors that may reflect the effects of implementing the IDD Directive include the number of complaints filed against insurance companies and intermediaries reported to organizations and institutions representing the interests of insurance company clients.Footnote 17 In this regard, data from the German and Polish markets are presented (Fig. 5).

Source: Authors; analysis based on: Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin), Annual Report 2021, Bonn and Frankfurt am Main, May 2022, p. 85. Reports of the Financial Ombudsman and their office on activities for 2017–2021

Number of complaints against insurance companies and insurance intermediaries in Germany and Poland in 2017–2021.

The presented data indicate a decreasing number of complaints reported against insurance companies and insurance intermediaries in the Polish market. Over the five years studied, the number of complaints decreased by over 35%. Is this a result of the implementation of the IDD Directive? This cannot be stated definitively. The implementation of the directive could certainly have contributed to such a decline. In the case of the German market, the number of complaints in 2017–2021 remains at a similar level. Additionally, there are years in which there has been an increase in the number of complaints. According to BaFin, the most common complaints reported by customers were related to the amount of compensation and benefits paid and the incorrect claims settlement process.

Development Opportunities and Prospects of Insurance Intermediation in the Light of the IDD Directive

The European insurance intermediation market exhibits significant diversity in terms of local distribution channels and varying definitions adopted at the national level. Additionally, registration practices and reporting procedures differ among Member States, further contributing to the heterogeneity of the European insurance mediation market.

EIOPA reports that a substantial 56% of all intermediaries operate within categories specific to individual Member States. This diversity and lack of uniformity pose challenges when it comes to drawing conclusions and conducting analyses of insurance distribution across Europe (EIOPA, 2018).

The evaluation of the implementation of the IDD Directive is not and will not be straightforward. A SWOT analysis can be conducted based on own research, as well as the responses provided to the EIOPA in the 2020 study (Table 9).

The primary strengths of introducing this directive include harmonizingFootnote 18 (EIOPA, 2023) regulations that vary across Europe and enhancing consumer protection by providing adapted insurance products (Hofmann et al., 2018; Marano, 2021b; Śliwiński & Marano, 2020). However, the main weakness of the regulations is their formalization, resulting in the time and expense required to protect consumers, who are protected by receiving more and more information (Ostrowska, 2021). Cost intensity extends to distributors who are increasingly burdened with meeting various requirements, which, according to some authors, may sometimes seem geared more towards regulatory compliance than genuinely expanding insurance coverage (e.g., as the ACS survey). A notable weakness of the Directive is the inadequacy of solutions for the digital sale of insurance products, which is becoming increasingly important.

The emergence of new risks (e.g., pandemics) and the rapid advancement of insurance distribution technologies/techniques represent significant threats. The format of documents and customer information may need to differ between traditional in-person distribution and online sales. Furthermore, online sales frequently occur through external channels, including insurtech companies, which adds complexity to the implementation of regulations stemming from the directive. Among the threats, attention should also be paid to the inconsistencies of the Directive with other (national) consumer protection legislation and the heterogeneous nature of Member States’ rules on insurance distribution (Köhne & Brömmelmeyer, 2018; Pscheidl, 2018).

One of the most significant opportunities, which has not yet been fully realized, with the implementation of this directive is the potential to enhance the level of satisfaction with insurance services. Improving satisfaction with the purchasing process and tailoring insurance products to the customer’s needs could lead to increased interest in insurance, particularly in regions where per capita spending on insurance is lower, such as Central and Eastern Europe (Insurance Europe, 2022b). This heightened interest could help mitigate the risk of adverse selection, as a broader spectrum of clients, including those with lower risk profiles, may choose to purchase insurance.

When analyzing the provisions of SWOT, it becomes crucial for individual legislators and regulators to enhance consumer awareness regarding the benefits stemming from the implementation of the IDD Directive. This can be achieved by overseeing not only regulatory compliance but also assessing their impact on the improvement of the products offered. Distributors should aim to boost customer satisfaction by providing adequate insurance coverage. This, in turn, may ultimately result in an increase in written premiums, driven by the provision of better-quality products.

Conclusions

The IDD aimed to standardize the distribution of insurance to consumers; however, the insurance distribution market within the EU remains characterized by its diversity and significant fragmentation. Various national distribution channels, registration prerequisites, and reporting frameworks are in place across EU member states.

Considering the relatively short duration of the IDD implementation and the typical delay in observing the effects of legislative changes, it is premature to arrive at definitive conclusions regarding IDD’s effectiveness. This is especially true for Member States that experienced delays in implementing the regulations. Furthermore, several other factors are influencing the market, including the COVID-19 pandemic and digitalization, making it challenging to discern the IDD’s specific impact on the insurance market from the broader influences shaping insurance distribution (EIOPA, 2022). The pandemic, as mentioned earlier, expedited ongoing technological changes in the insurance distribution landscape.

Nonetheless, the initial findings presented indicate that despite the substantial increase in procedural requirements and associated financial costs for insurers, there has not been a commensurate improvement in the quality of insurance services, particularly in terms of their suitability for consumers. Consumers have encountered heightened formalities without a corresponding enhancement in product quality, which might have otherwise stimulated greater interest in insurance and consequently reduced the prevalence of anti-selection in insurance. Consequently, the challenge confronting the markets in Member States goes beyond mere regulatory harmonization; it also, or perhaps primarily, involves raising consumer awareness about the advantages stemming from the IDD Directive.

Despite the constraints imposed by data limitations and the relatively short experience with the implementation of the IDD, this study sought to offer an initial overview of the effects of the IDD on consumers, insurance distributors, and regulatory practices.

Insurance is a unique financial product, primarily centered around risk rather than investment, which is often incorrectly perceived by customers. Furthermore, recognizing that clients do not always, or often do not, make rational decisions, economics and behavioural finance play a crucial role. Regulatory efforts should draw upon insights from these fields. Simply imposing obligations on distributors and striving for harmonization across Europe will not be sufficient if it does not address the way people make purchasing decisions. Appropriately modified—in accordance with the principles of behavioural economics—analysis of customer needs can help to mitigate issues like overconfidence and the tendency to view insurance premiums as losses. Future regulations should place a stronger emphasis on educating consumers, enhancing financial awareness, and improving financial literacy, efforts that should be collaborative between regulatory bodies and Member States. The relatively short timeframe of these regulations should not deter meaningful changes to existing practices.

The conclusions presented in the paper relate to research on the harmonization of insurance distribution, as each country can increase the minimum level of consumer protection and improve state policy on this protection. The protection referred to comes from a directive adopted in 2016, but work on it began many years earlier, so the rules apply to the analog customer, i.e., the one who mainly buys insurance in person, stationary, i.e., the de facto customer, whose market share has been declining in recent years.

As indicated in the SWOT analysis, it is important for individual legislators and regulators to raise consumer awareness of the benefits of the IDD. However, the real benefits must clearly outweigh the costs associated with the obligations introduced. The above information for insurance consumers is important to ensure and enforce their rights and to contribute to market stability and development. This development, in turn, can be achieved not only by monitoring compliance with the rules introduced, but also and above all by increasing their impact on the quality of the product offered, which is often distributed via the Internet.

In conclusion, it is evident from the research presented in this paper that further work and assessment of the regulations introduced thus far are necessary.

Data Availability

We used secondary data, all data sources are publicly available and are provided in the paper.

Notes

In the following chapter, the term “consumer” will be used interchangeably with “client,” although a client refers to anyone benefiting from insurance protection. However, a consumer can only be considered a natural person who acts for purposes other than their trade, business, craft, or profession (Regulation (EU) 2017/2394 of the European Parliament and of the Counicil of 12 December 2017 on cooperation between national authorities responsible for the enforcement of consumer protection laws and repealing Regulation (EC) No 2006/2004. OJ L 345, 27.12.2017).

In 2020, the insurance premium to GDP ratio (penetration) averaged 7.43% in Europe. The lowest value was recorded in Romania at 1.2%, while the highest was 11.2% in Denmark.

These data are not entirely comparable, as this report states that there were 683 insurers operating in France in 2020, which differs from the figure of 665 presented in Table 1.

It is worth noting that in Poland, the share of employees working directly for insurance companies was around 30% (referred to as “direct writing”), whereas bancassurance accounted for approximately 20% (this marked a significant decrease from previous figures, as bancassurance's share was nearly 30% before this change).

For instance, in 2023, during EIOPA’s consultation on capital requirements and sustainable development in Poland, concerns were raised regarding the risks for insurers associated with holding corporate bonds issued by companies involved in coal-based energy production.

The concept of homo economicus is based on several main assumptions: individuals are rational, individuals have and act on the basis of complete and perfect information, decisions are aimed at maximizing expected utility or profit maximization, and they only consider their own interests and benefits.

The behavioral economics perspective on the insurance market is important for two reasons. Firstly, it can help understand customer behavior in this market, but mainly, it can help induce a change in behavior towards better insurance protection.

Additionally, Kahneman and Tversky showed that individuals are risk averse in the area of gains and risk prone in the area of losses, which was called the reversal effect.

A particular example of this may be the presentation of pension security products Y.

GR, HU, IE, and NL provided information on the number of insurance intermediaries only for the years 2019 and 2020. LT presented limited information for the years 2016–2019.

This includes registered intermediaries offering supplementary insurance and does not include intermediaries offering exempted supplementary insurance under the IDD.

For example, insurance agents typically operate on behalf of one insurance company (individual agents) or on behalf of more than one insurance company (agency).

For example, insurance brokers typically operate on behalf of the client and collaborate with multiple insurance companies to help the client meet their insurance needs. Unlike insurance agents, insurance brokers do not have a direct contractual relationship with one or a few insurance companies to operate on an exclusive basis.

For example, in the Czech Republic, registered intermediaries offering supplementary insurance may simultaneously represent insurance companies and insurance intermediaries, thus falling into two categories. In two member states, intermediaries cannot act on behalf of another intermediary (PL) or on behalf of more than one intermediary (HU).

The demand side of the insurance market was represented by 12 entities (mostly entities representing consumer rights, e.g., the Romanian Asociatia Consumers United/Consumatorii Uniti), and the supply side by 58 entities.

Given the limited sample size, it was not feasible to apply the independence test for all the questions (“increasing the duties and responsibilities of the intermediary;” “positive impact of the IDD on the market;” “neutral impact of the IDD on the market”).

In the German market, it is the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin), whereas in the Polish financial market, it is the Financial Ombudsman (Rzecznik Finansowy—RF).

IDD is a minimum harmonization directive, Member States can introduce additional provisions or bring additional activities into the scope of the regulations.

References

Arena, M. (2008). Does insurance market activity promote economic growth? A cross-country study for industrialized and developing countries. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 75(4), 921–946. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6975.2008.00291.x

Bayar, Y., Gavriletea, M. D., & Danuletiu, D. C. (2021). Does the insurance sector really matter for economic growth? Evidence from Central and Eastern European countries. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 22(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2021.14287

Bekhzodovna, U. K. (2023). Current trends in the insurance market. World of Science: Journal on Modern Research Methodologies, 2(2), 17–20.

Bernardino, G. (2015). Insurance distribution in a challenging environment. The European Federation of Insurance Intermediaries (BIPAR). https://register.eiopa.europa.eu/Publications/Speeches%20and%20presentations/2015-06-05%20BIPAR%20meeting.pdf

BIPAR. (2023). Insurance Intermediation. The European Federation of Insurance Intermediaries (BIPAR).

Blazheska, A., & Ivanovski, I. (2021). Determinants of the market choice and the consumers behavior on the Macedonian MTPL insurance market: Empirical application of the Markov chain model. Risk Management and Insurance Review, 24(3), 311–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/rmir.12192

Brighetti, G., Lucarelli, C., & Marinelli, N. (2014). Do emotions affect insurance demand? Review of Behavioral Finance, 6(2), 136–154. https://doi.org/10.1108/RBF-04-2014-0027

Bristow, B. J., & Tennyson, S. (2001). Insurance choices: Knowledge, confidence and competence of New York consumer. Final report. Cornell University.

Brown, J. R., Kling, J. R., Mullainathan, S., & Wrobel, M. V. (2008). Why don’t people insure late-life consumption? A framing explanation of the under-annuitization puzzle. American Economic Review, 98(2), 304–309. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.2.304

Brown, J. R., Kling, J. R., Mullainathan, S., & Wrobel, M. V. (2013). Framing lifetime income (Working Paper 19063). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w19063

Browne, M. J., & Hoyt, R. E. (2000). The demand for flood insurance: Empirical evidence. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 20(3), 291–306. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007823631497

Coats, J., & Bajtelsmit, V. (2021). Optimism, overconfidence, and insurance decisions. Financial Services Review, 29(1), 1–28.

Cummins, J. D., & Doherty, N. A. (2006). The economics of insurance intermediaries. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 73(3), 359–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6975.2006.00180.x

Czerwonka, L. (2015). Behawioralne aspekty decyzji inwestycyjnych przedsiębiorstw. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego.

Drees. (2022). Sur la situation financière des organismes complémentaires assurant une couverture santé. https://drees.solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/2022-12/Rapport2022.pdf

Driver, T., Brimble, M., Freudenberg, B., & Hunt, K. (2017). Insurance literaty in Australia: Not knowing the value of personal insurance. Financial Planning Research Journal, 4(1). https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0030/295770/FPRJ-V4-ISS1-pp-53-75-insurance-literacy-in-australia.pdf

Eckert, C., Eckert, J., & Zitzmann, A. (2021). The status quo of digital transformation in insurance sales: An empirical analysis of the german insurance industry. Zeitschrift Für Die Gesamte Versicherungswissenschaft, 110(2), 133–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12297-021-00507-y

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority. (2018). Insurance distribution directive – evaluation of the structure on insurance intermediaries markets in Europe. https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/system/files/2019-03/idd_evaluation_of_intermediary_markets_0.pdf

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority. (2020). Survey on the application of the Insurance Distribution Directive (IDD). https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/consultations/survey-application-insurance-distribution-directive-idd_en

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority. (2022). Report on the application of the Insurance Distribution Directive (IDD). https://dgsfp.mineco.gob.es/es/supervision/Documentos%20EIOPA1/2022/report_on_the_application_of_the_idd.pdf

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority. (2023). Insurance Distribution Directive (IDD). https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/browse/regulation-and-policy/insurance-distribution-directive-idd_en

European Commission. (2008). Financial services provision and prevention of financial exclusion. https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/geography/migrated/documents/pfrc0806.pdf

Focht, U., Richter, A., & Schiller, J. (2013). Intermediation and (mis-)matching in insurance markets—Who should pay the insurance broker? Journal of Risk and Insurance, 80(2), 329–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6975.2012.01475.x

Forlicz, M., & Rólczyński, T. (2018). Skłonność do ubezpieczania się w warunkach niepewności w zależności od wysokości potencjalnej straty. Studia Ekonomiczne, 366, 135–144.

Gallouj, C. (1997). Asymmetry of information and the service relationship: Selection and evaluation of the service provider. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 8(1), 42–64. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564239710161079

Gnath, K., Grosse-Rueschkamp, B., Kastrop, C., Ponattu, D., Rocholl, J., & Wortmann, M. (2019). Financial market integration in the EU: A practical inventory of benefits and hurdles in the Single Market [Other]. http://aei.pitt.edu/102686/

Goedde-Menke, M., Lehmensiek-Starke, M., & Nolte, S. (2014). An empirical test of competing hypotheses for the annuity puzzle. Journal of Economic Psychology, 43, 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2014.04.001

Gorlewski, B. (2010). Podejście behawioralne w naukach ekonomicznych. Przykład ekonomiki transportu. In Nauki ekonomiczne w świetle nowych wyzwań gospodarczych. Szkoła Główna Handlowa.

Graminha, P. B., & Afonso, L. E. (2022). Behavioral economics and auto insurance: The role of biases and heuristics. Revista De Administração Contemporânea, 26, e200421. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-7849rac2022200421.en

Gutter, M. S., Garrison, S., & Copur, Z. (2010). Social learning opportunities and the financial behaviors of college students. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 38(4), 387–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-3934.2010.00034.x

Gysler, M., Brown Kruse, J., & Schubert, R. (2002). Ambiguity and gender differences in financial decision making: An experimental examination of competence and confidence effects. Working Papers / WIF, 2002(23). https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-a-004339594

Harrison, G. W., & Ng, J. M. (2016). Evaluating the expected welfare gain from insurance. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 83(1), 91–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/jori.12142

Hinrichs, G., & Bundtzen, H. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on personal insurance sales–evidence from Germany. Financial Markets, Institutions and Risks, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.21272/fmir.5(1).80-86.2021

Hofmann, A., Neumann, J. K., & Pooser, D. (2018). Plea for uniform regulation and challenges of implementing the new insurance distribution directive. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance - Issues and Practice, 43(4), 740–769. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41288-018-0091-6

Hogarth, R. M., & Kunreuther, H. (1989). Risk, ambiguity, and insurance. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 2(1), 5–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00055709

Howells, G. (2020). Protecting consumer protection values in the fourth industrial revolution. Journal of Consumer Policy, 43(1), 145–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-019-09430-3

Insurance Europe. (2020). European Insurance key facts. Insurance Europe. https://www.insuranceeurope.eu/publications/2570/european-insurance-key-facts-2020-data

Insurance Europe. (2022a). Annual Report 2021–2022. https://insuranceeurope.eu/publications/2620/annual-report-2021-2022/download/Annual+Report%202021-2022.pdf

Insurance Europe. (2022b). European insurance in figures. Insurance Europe. https://insuranceeurope.eu/publications/2569/european-insurance-in-figures-2020-data

Insurance Europe. (2022c). Statistics. https://www.insuranceeurope.eu/statistics

Jedynak, T. (2022). Behawioralne uwarunkowania decyzji o przejściu na emeryturę. C.H.Beck.

Kadoya, Y., Rabbani, N., & Khan, M. S. R. (2022). Insurance literacy among older people in Japan: The role of socio-economic status. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 56(2), 788–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12448

Kahneman, D. (2003). Maps of bounded rationality: Psychology for behavioral economics. The American Economic Review, 93(5), 1449–1475.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

Köhne, T., & Brömmelmeyer, C. (2018). The new insurance distribution regulation in the EU—A critical assessment from a legal and economic perspective. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance - Issues and Practice, 43(4), 704–739. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41288-018-0089-0

Krupa, D., & Walczak, D. (2016). Savings of households run by self-employed persons in rural areas in Poland. In B. Mehmet Huseyin, D. Hakan, D. Ender, & C. Ugur (Eds.), Business challenges in the changing economic landscape—Vol. 2 (pp. 457–467). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22593-7_34

Kunreuther, H., Michel-Kerjan, E., & Pauly, M. (2013a). Making America more resilient toward natural disasters: A call for action. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 55(4), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2013.803884