Abstract

Consumer protection is an integral part of the current phase of the European integration project. However, eclipsed by market-building, the image of European consumers is homogeneously defined by individual economic interests against a uniform metric. This article proposes the alternative image of an “embedded consumer” to align with the imaginary of the constitutional person under primary EU law, especially the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. Under the Charter, a constitutional person is fundamentally shaped and significantly enabled by their communities and thus bears “duties and responsibilities” towards the community. This obligation does not always amount to individual legal responsibility as individuals are inevitably vulnerable (when social structures lack fairness) and rely on social institutions to build up their resilience. Accordingly, the embedded consumer is also socially responsible and humanly vulnerable. This entails that a responsible consumer policy should move beyond individual responsibilisation and involve public obligations and corporate responsibilities to create a conducive framework for sustainable and responsible consumption. A responsible framework is a balanced one, on the one hand, which consciously navigates the conflicts between the various rights of the consumer as a person and between the consumer’s rights and the community’s interests. On the other hand, it also takes consumer vulnerability as the starting point for consumer policy. Such an “embedded consumer” is not merely futuristic but represents a transformation underway in the EU. EU consumer law and policy should be informed by the embedded consumer and the collective vision it reflects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Consumer protection is part and parcel of the current phase of the European integration project. It aims to empower consumers against stronger market actors and enable informed decisions and (digital) market confidence. Indeed, 69% of individual internet users in the EU bought or ordered products or services online in 2023 (Eurostat, 2024), and private consumption accounted for 51.4% of the EU GDP in December 2023 (CEIC Data, 2024). However, it is becoming ever more visible that the goods and services we consume—the garments we wear (e.g., European Parliament, 2020), the digital gadgets we use (e.g., Dimri, 2022), and the coffee we drink (e.g., Food Empowerment Project, 2019)—might not be ethically and sustainably produced. The ecological implications of mass production and consumption are also staggering—two-thirds of greenhouse gas emissions are related to household consumption (Ivanova et al., 2020). Meanwhile, Art. 3 of the Treaty on European Union (“TEU”) mandates the EU to strive for the “sustainable development of Europe” and “a highly competitive social market economy” to promote “the well-being of its peoples.” It is increasingly clear that such a “social market economy” is not only about economic efficiency but also about just and sustainable practices. What does this mean for the consumer protection regime that we have today, so that the well-being of European “peoples”—not just that of the “consumers”—is safeguarded?

When we speak of consumer protection, it is not only about the technical rules that lay out the details of particular consumer rights; it is also about the legal “image” of who consumers are that all the nitty–gritty rules presuppose—or create. As embodied in the “average consumer” benchmark, European consumer law predominantly portrays consumers to be rational economic actors and thus devises most consumer protection rules along that line. It may well suit the story of market building, but in times of overlapping ecological and social crises, such a lopsided framing distorts the reality we perceive through it and stands in the way of social transformation. A multifaceted person is institutionally reduced to a mere market participant. In this light, to free us from the economic bias of consumer law, it is helpful to reassess and reframe the legal image of consumers in order to give a full presentation of the various facets of consumer experience: their needs and wants, their capability and vulnerability, their individual agency and collective situatedness. Only with a full picture of who consumers are can we start a serious discussion of what kind of protection they really need.

This paper seeks to reframe the legal image of consumers as an “embedded consumer.” I submit that consumers in the “social market economy” should be embedded into the broader constitutional vision of a just and sustainable collective future in the EU. The just prong is systematically presented in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (“CFREU” or “Charter”) while the sustainable mandate is captured by Art. 11 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”) and, verbatim, Art. 37 of the Charter. In this paper, I will start with a brief overview of how the European consumer is made through EU law and policies in order to reveal the historical contingency as well as the systematic impact of the economic consumer (“The making of the European consumer”). I then move to discuss how the CFREU, informed by Art. 11 TFEU, envisages a constitutional person as its subject matter, which I will use as the analytical framework to frame the embedded consumer (“The “embedded consumer”: reframing the consumer image against the constitutional person”). It is submitted that a constitutional person under the CFREU is socially responsible and humanly vulnerable. I will arrive at this image by situating the CFREU in the historical development of (international) human rights law as well as political philosophy theories. With the profile of the embedded consumer, I will proceed to tease out its policy implications, namely a balanced approach and a vulnerability approach in EU consumer law and policy (“Extended policy implications”). Finally, I will take a step back to the current state of EU consumer law to shed some light on whether the embedded consumer is merely futuristic or captures a transformation that is underway (“A transformation underway? Taking stock of European consumer policy”).

The Making of the European Consumer

Consumer protection is a core constituent of the European integration project. In the making of European consumer law, the EU has to pinpoint its own conception of who consumers are, namely the “image(s)” of consumers (e.g., Leczykiewicz & Weatherill, 2016). Over the years of the development of EU consumer policy, the image of European consumers has at least two prominent features. First, consumers are seen as “weaker parties” who are economically fragile and susceptible to market harm by more powerful market actors (e.g., Hondius, 2004; Meli, 2006). This aspect was most prominent in the early years of EU consumer policy. In 1975, the EU issued its very first consumer policy document, which was strongly based on a rationale of weaker party protection. As the market evolves, businesses have “a greater opportunity to determine market conditions than the consumer,” making the latter “no longer able properly to fulfil the role of a balancing factor” (Council resolution, 1975, para. 6). Public intervention is thus necessary to “correct the imbalance of power” (Council resolution, 1975, para. 7). As further illustrated by the Court of Justice of the EU (“CJEU”), consumers’ weak position derives from asymmetry in information or expertise (e.g., Karel de Grote [2018], para. 59) or bargaining power (e.g., Costea [2015], para. 27). Second, at times conflictingly, consumers are also viewed as highly rational market actors, who, with the correct information, are able to make informed decisions in their best economic self-interest (e.g., Wilhelmsson & Twigg-Flesner, 2006). In other words, consumers are presumed to be “homo economicus” in line with neoclassical rational choice theory (Posner, 1998). This assumption manifests itself in the information paradigm pervasive in European consumer law (Micklitz et al., 2010). Consumer protection through more information was already the key approach in the first consumer policy (Council resolution, 1975; GB-INNO-BM [1990], para. 14) and remained the focus in the most recent one (European Commission, 2020; Terryn, 2021).

These two seemingly inconsistent accounts are threaded in a consistent story of the instrumentalisation of consumers to serve the making of the internal market (e.g., Bartl, 2015; Michaels, 2011; Schmid, 2005; Unberath & Johnston, 2007). EU consumer policy is the “essential corollary of the progressive establishment of the internal market” (European Commission, 2002). The rationale for consumer protection is expressed as “giv[ing] consumers the means to protect their own interests by making autonomous, informed choices” (European Commission, 2002). A single market requires a single, homogeneous image of consumers as its constituent—famously known as the “average consumer” who is “reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect” (e.g., Gut Springenheide [1998], para. 31; Recital 18 of the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive 2005). Though the direct application of the “average consumer” is mostly found in the context of combating unfair commercial practices, its normative directionality has undoubtedly permeated the design of European consumer law. In this light, consumers are presumed to be highly homogeneous. They have the same end: consumer law instruments, first and foremost, aim at guarding consumers’ economic interests as if they only want to search for lower prices and better bargains in the marketplace. Consumers also have the same means: EU consumer protection is uniformly extended to all consumers against uniform standards, with ever more fully harmonised instruments. Protection for “vulnerable consumers” does exist, albeit only in narrow and exceptional cases (e.g., Art. 5(3) of the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive 2005, Recital 34 of the Consumer Rights Directive 2011; Waddington, 2013). The “protection” of consumers (through regulation) as a weaker party is redirected to the “empowerment” of consumers (with information) as a rational market actor (Howells, 2005; Micklitz, 2012; O’Reilly, 2023). To an extent, the “average consumer” is not the starting point of European consumer policy but the end product of the EU’s regulatory choices (Dani, 2011; Mak, 2016).

More importantly, against the broader global political economy, the making of the economic consumer is part and parcel of the rise of neoliberalism since the 1980s (Herrine, 2022; Olsen, 2019) and is fundamentally underpinned by the neoliberal socio-economic imaginary—more specifically in the EU context, the making of the internal market (Bartl, 2015, 2020). With ever more privatised sectors, more and more aspects of our lives are presented as and commodified into available “consumables” in the market and thus become measurable in economic terms. Within certain sectors such as telecommunications, energy and transport, in particular, EU law, through its liberalisation and privatisation measures, legally created the identity of consumers, thereby “turn[ing] citizens, with a right to a public service (not for profit), into consumers of private services (for profit), with a right to consumer protection” (Hesselink, 2023, p. 419). Privatisation is coupled with financialisation: public welfare is taking a back seat to private debt-taking (Comparato, 2018; Domurath, 2016). Less privileged citizens are invited to join the market to pursue their conceptions of good living as “sovereign consumers,” outsourcing social provisioning to consumers’ individual decisions and redirecting democracy away from redistribution to the facilitation of free choices (Herrine, 2022; Olsen, 2019). Through the neoliberal subject-remaking programmes, consumers are legally thinned to fixate on price and bargains to conform to the needs of market optimisation. On being told that the homo economicus is like us, we become more like him. The responsibility of consumers, if any, is all about acting as confident self-entrepreneurs in the neoliberal market and expanding their “capacity for “self-care”—their ability to provide for their own needs and service their own ambitions” (Brown, 2006, p. 694). In line with such an imaginary, the normative image of EU consumers is a one-dimensional, homogenous, and atomistic individual, who aims at maximisation of self-interests in the market.

Let us take a closer look at the EU’s periodical consumer policy papers to see how the image of consumers has been made a proxy of the EU’s political agenda. As mentioned, back in 1975, EU consumer policy started as a project of weaker party protection. Such an approach underpins the imagination of the welfare state (Micklitz, 2020). The view that consumers and businesses co-thrive in a growing market pie without any conflicts is rejected while a picture of the “common good”—through collective struggles and balancing of conflicting interests – is advanced (Bartl, 2020, pp. 242–243). In 1998, the “Consumer Policy Action Plan 1999–2001” put forward that EU consumers policy should ensure that “consumer interests are equitably reconciled with those of other stakeholders,” including those of businesses. Consumers should thus be willing to accept “trade-offs” between their identity as consumers and as “taxpayers, employees and beneficiaries of public policies” and assume “responsibilities” to reconcile their “immediate interests […] with longer-term concerns for the environment and society” (European Commission, 1998). Such a vision of the responsible consumer plants the (conflicting) seeds for both a conscious consumer who is willing to compromise self-interest for the community good and a confident consumer who is able to care for her own well-being by joining the internal market. From the later development, it is clear that the latter has thrived (e.g., Twigg-Flesner, 2016; Wilhelmsson, 2004). Consumer protection became secondary to market building, while the misleading vocabulary of “confident, informed and empowered consumers” took a strong hold (European Commission, 2007). “Empowered and confident consumers can drive forward the European economy.” (European Commission, 2012) It was only in recent years that the EU also started to draw attention to challenges like “information overload,” “sustainable consumption,” and “social exclusion […] and accessibility” (European Commission, 2012), yet without really taking substantive steps to change the status quo.

Such a model of consumer protection is coupled with serious economic, social and environmental implications—which did not go unnoticed by the EU. Due to its economic focus, European consumer law embodies a structural “consumerist bias” (Wilhelmsson, 1998, p. 47) by promoting ever more production and consumption. With more available consumer products, more resources are consumed, more pollution is created, and more waste is generated, compounded by the risk of human rights violations along the value chain (e.g., Terryn, 2023). Due to its uniform metric, consumer law excludes the very weak and vulnerable consumers who do not fit into the market archetype but who actually need the protection most (Micklitz, 2012). As opposed to maximising consumer welfare, consumer markets are reproducing social inequality and engendering regressive redistribution (e.g., Bartl, 2015). For example, sociologists have observed that “the poor pay more” for their products, services, and credit (Caplovitz, 1963; Squires, 2004). Due to its individualistic approach, the monistic consumer is disembedded from the social realisation of consumption and unencumbered by the impact of consumption on the community. Consumers lose touch with their moral instincts and community bonding. Though these risks are not new, the exponential boom in private consumption, the intricacies of globalised value chains, and the fast-paced growth of the online marketplace have amplified them to a level beyond what early economists and policymakers accounted for in their models. We should not be trapped in their antiquated vision so rigidly that it hampers our ability to tackle the current crises.

In light of the interconnectedness of consumption and wider societal and environmental issues, it is imperative to move away from the siloed consumer law that exclusively addresses the economic capacity of human beings and adopt a holistic approach to align consumer law with broader societal objectives. Institutionally, the delineation of the economic consumer by the EU could further restrict the autonomy and experimental freedom of Member States in deference to the internal market, stifling national initiative and undermining the democratic and reflexive multi-level governance in the EU (e.g., Terryn, 2023; Weatherill, 2014). To this end, an ontological reorientation of the legal image of consumers lends itself as a starting point for a holistic and democratic consumer policy. The discussion has already been spearheaded by several prominent scholars (e.g., Mak, 2022; particularly on the “consumer-citizen,” e.g., Davies, 2011; Mak & Terryn, 2020; Porter, 2020). Of course, it should be noted that the consumer image discussed here is not an empirical or statistical portrait of any single consumer; it is a legal and normative benchmark that informs the objectives and directions of consumer law and policies. In other words, such a legal image is not about a realist sketch of consumers’ identities and behaviours but rather a normative positioning of consumers in the political economy regarding how they should be protected. It offers a framing that sets our expectations for market actors and redefines the nature, dynamics, and boundaries of the consumer market as a form of social organisation.

The “Embedded Consumer”: Reframing the Consumer Image Against the Constitutional Person

To get rid of the one-dimensional, homogenous, and atomistic consumer, we need to rethink the socio-economic imaginary in which a consumer is situated. Inspired by Polanyi’s thesis on the embeddedness of the economy in non-economic institutions,Footnote 1 I argue that European consumers first and foremost should be seen as constitutional people, who are embedded into the vision of the EU towards a just and sustainable collective future—which I will call the “embedded consumer.” Such a vision is captured in EU primary law. Art. 3 TEU defines the objectives of the EU as working for the “sustainable development of Europe” and “a highly competitive social market economy” to promote “the well-being of its peoples.” More specifically, the social limb of justice is systematically enshrined in the CFREU while the ecological aspect of sustainability is unequivocally present under Art. 11 TFEU which provides for an all-encompassing environmental integration obligation for all EU policies.Footnote 2 Given that Art. 11 TFEU is verbatim incorporated into Art. 37 of the Charter, this article will mainly consider the embedded consumers against the edifice of the Charter.

Before moving on, a few more words on the relevance of the CFREU to EU consumer law are in order. On the one hand, the Charter represents the EU’s transition from a prevalently economic Union to a more political and social union by making fundamental rights more visible and central to the integration process. Under Art. 6 TEU, the fundamental rights in the CFREU “have the same legal value” as the primary EU treaties. Secondary EU law, including consumer legislation, should thus be consistent with the values and principles of the CFREU. On the other hand, though consumer-to-business relationships are traditionally characterised as horizontal relationships that fall outside the strict scope of constitutional law, the constitutionalisation of private law on the EU level is underway and ongoing (e.g., Colombi Ciacchi, 2014; Mak, 2013b; Hartkamp, 2010; Reich & Cherednychenko, 2015; Spaventa, 2011). Fundamental rights thus have a significant say in consumer relationships (Benöhr, 2013; Collins, 2017; Hesselink, 2007; Iamiceli, Cafaggi & Artigot-Golobardes, 2022). Particularly, under Art. 38 CFREU, together with Arts. 12 and 169 TFEU, consumer protection itself is part of the EU constitutional order in a broad sense. Increasingly, (general) references to the Charter are explicitly made in consumer legislation (e.g., Recital 25 of the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive 2005; Recital 66 of the Consumer Rights Directive 2011, Recital 72 of the Sale of Goods Directive 2019). Of course, fundamental rights are highly indeterminate (e.g., Hesselink, 2017; Kennedy, 2002), and the Charter itself is susceptible to improper interpretation (e.g., Weatherill, 2014). Yet, the approach taken here does not hinge on any specific fundamental right as an individually invocable claim but builds on the system of the Charter to derive normative guidelines for EU consumer policy. Bearing these in mind, in the following part, I move to analyse what a person under the CFREU looks like in a moral sense, what it means for policy in a normative sense, and how it informs the framing of the “embedded consumer” as a constitutional person.

The Constitutional Person as a Responsible Member of Community

Modern human rights emerged out of a political history of liberalism, arming individuals with the arsenal of civil and political rights to fend off unwarranted intervention from an overly dominant and potentially hostile state (e.g., Langlois, 2016; Moyn, 2010). However, with the changing patterns of society and the newly rising threats to freedom such as gross inequality, corporate capture, and climate change, the normative priorities as well as the concrete provisions of human rights are (and should be) also evolving (Düwell, 2013). The Charter, emerging at the dawn of the twenty-first century during the EU’s shift towards a more politically and socially oriented union, embodies the culmination of various generations of human rights (Vasak, 1977), taking into account “changes in society, social progress and scientific and technological developments” (the preamble of the Charter). Its scope ranges from civil and political rights (such as the right to liberty, Art. 6 CFREU) to social and cultural rights (such as the right to education, Art. 14), from individual rights to solidarity rights (such as the right to social security, Art. 34). The imperative of environmental protection, though not a right in itself, is also part of the Charter’s order (Art. 37). Such a pluralistic vision of human life enriches the human rights agenda with a collective grammar beyond its liberal traditions. The Charter is not only a political declaration of individual freedom vis-à-vis the political state but also a social compass for inclusion, care, and cooperation vis-à-vis a collective community. In its preamble, the Charter presents a balanced view of individual freedom and community interests and calls for responsible personhood: The “[e]njoyment of [Charter] rights entails responsibilities and duties with regard to other persons, to the human community and to future generations.” It is thus crucial to read the Charter and its envisaged person through the communitarian lens.

From a communitarian perspective, individual preferences are socially shaped, and individual wants are socially realised. On the one hand, as humans are social beings, our identity and preferences (who we are and what we value) are inevitably situated in our varying cultural backgrounds and inextricably linked to our social exchanges in our communities (e.g., Kymlicka, 1989; Taylor, 1989). No meaningful choices—the essence of the liberal mandate—are abstractly made in a social vacuum. The process of “subjectification” of the selves is a dialectical struggle between individuality and its shaping “forces, practices, and relations that strive or operate to render human beings into diverse subject forms” (Rose, 1998, p. 171). On the other hand, in a modern society that runs on the division of labour, personal realisation is fundamentally enabled by a system of “organic solidarity” that features social interdependencies and cooperation (Durkheim, 1984). The realisation of the self and her choices is not a self-sufficient enterprise but rests upon “background conditions” (Choi, 2015, p. 260) such as cultural ethos, social institutions—and natural resources. The boundaries of the community include not only humans and social relationships but also nature (Leopold, 2020). An excessive emphasis on sovereign, self-sufficient individuals and their rights justifies the neglect of mutual care and social responsibility and ultimately undermines social solidarity and backfires to undermine the appeals of rights themselves (Glendon, 2008; Koskenniemi, 1999).

Based on the connection and interdependence between individuals and communities, ontologically, we move from a liberal individual with abstract autonomy to a social being who turns to the community to define and realise herself. As such, individuals cannot be viewed as “unencumbered selves,” free and independent from the “moral or civic ties they have not chosen” (Sandel, 1998, p. 6; Sandel, 1984) but should bear responsibilities to their shaping and enabling communities. We have an obligation to recognise and value the various forces and contributions that together shape ourselves and our community life (Sandel, 2020). We should “support the institutions, associations, and infrastructure that in turn support the special sort of culture in which we live [and] within which each person is able to experience life-defining freedom and to create their own personal identities” (Alexander, 2018, p. 53). Along this line, human rights should move away from the misguided focus on individual freedom and be embedded into broader societal objectives such as respect, care, and responsibility (Fredman, 2008). Individual autonomies should be extended to social autonomies, wherein fundamental rights function not only to liberate but also to set boundaries for these social autonomies. (Wielsch, 2017). The pluralistic list of enshrined rights under the CFREU represents both our various social roles in the community and the various forces of our social life that enable social cooperation and that deserve recognition. The rights-entail-duties declaration in the preamble of the CFREU further confirms the image of the community-embedded selves and their moral obligation to sustain the community to which they owe their identities and self-realisation.

The Constitutional Person as a Vulnerable Product of Institutions

Individuals’ duties towards their enabling community do not always amount to their legal obligations to lead a responsible life. The individuals’ dependence on social, cultural, and institutional arrangements entails that their sense of irresponsibility and unencumbrance at the individual level can often be traced back to institutional failures at the collective level. Namely, an individual’s ability to perform her obligation is also intimately tied to the community setting. While community enables us to form identities and develop capabilities, unfair social structures also burden its members with inescapable vulnerabilities. As argued by Fineman (2008, 2012, 2019, 2020), vulnerability is an inherent human condition beyond individual control. In an unjust social and institutional structure, we are all susceptible to (sometimes temporary) vulnerability throughout the course of our lives. Of course, we experience this vulnerability uniquely through our own bodies, so our individual stories with vulnerabilities significantly vary in magnitude and potential (Fineman, 2008, p. 10). In other words, the notion of vulnerability is paradoxically both universal and particular. It differs not only based on personal characteristics—such as age, gender and race—but also on the situational interplay between their personal circumstances—say unemployment and sickness—and the wider economic and social settings and conditions—think of financial crises and global pandemics (Casla, 2021). Consumers are likewise vulnerable subjects. Systemic power imbalance in the market puts consumers in a structurally vulnerable position. Meanwhile, consumers also experience various forms of vulnerability through their unique bodies and stories. The assumption of the “average consumer” is an inaccurate and even harmful framing of who consumers really are.

A social reading of vulnerability invites us to unsettle the unchallenged presumptions by asking what we share as human beings, what we can expect from laws and the underlying social structures, and what kind of relationship we want between society and its affected lives (Fineman, 2019, p. 342). Our shared vulnerability reminds us to “reach out to others, form relationships, and build institutions” as it is also our shared responsibility to ensure that no one is left behind (Fineman, 2012, p. 126). Yet, though neighbourly support and mutual aid are undeniably crucial and deservingly commendable, they cannot replace the responsibility of the state to be responsive, as it is a main actor in engineering social institutions and thus plays a central role in addressing the dynamics between individuals and communities. A responsive state should not only remedy past discrimination but also create just and inclusive social institutions that enhance the future resilience of vulnerable subjects and that do not breed injustices in the first place (Fineman, 2020; Scholz, 2014). Law and politics should reveal, sustain, and democratise the communal ties and social forces that shape our identities and vulnerabilities. They should create a collective atmosphere that promotes care and responsibility and cultivate a responsible and resilient citizenry. The blanket rejection of legal paternalism for fear of interference with individual choices and imposition of certain lifestyles (on the wrongness of paternalism, Cornell, 2015) often results in those choices being manipulated by other—often less democratic and transparent—social and commercial forces, which might further entrench and perpetuate irresponsibility and vulnerability. To regard individuals as vulnerable subjects of the law is thus not to deny them their agency but to socially contextualise their autonomy; it is to free those individuals from the social structures that suppress their full potential and sever their bonds to their shaping and enabling community.

The notion of “vulnerability” has been gathering momentum in human rights discourse and practice. The Charter has indeed placed the protection of the vulnerable at its core. It moves beyond the abstract person but focuses on particular features of vulnerable individuals and groups, including gender (Art. 23 CFREU), age (Arts. 24, 25), and disability (Art. 26), aiming at substantive equality among persons. Two comprehensive principles of equality (Art. 20) and non-discrimination (Art. 21) are instituted to further cover any possible discrimination. Moreover, the Charter takes a step further from anti-discrimination to collective resilience-building by promoting the set-up of solidarity projects and institutions that collectively pool and redistribute social risks and extend assistance to those (temporarily) in need, in the form of, for example, social assistance (Art. 34) or healthcare benefits (Art. 35). It is clear that the Charter mandates the EU to take active measures not only to enable freedom but also to promote integration into and participation in society and community life (e.g., Arts. 24 and 25 CFREU). The realisation of various fundamental rights directly necessitates the building and maintenance of communities and institutions, such as schools for the right to education (Art. 14) and hospitals for the right to health (Art. 35). Ultimately, a free and responsible lifestyle, where we care about each other, value communities and revere nature, is the result of a social infrastructure, where solidarity projects are put in place, vital institutions are properly maintained and environmental protection is duly enforced.

The Consumer as a Constitutional Person

“Consumers, by definition, include us all.” (Kennedy, 1962) Every person consumes, and we are united in the collective identity of consumers. It seems superfluous to claim that a consumer is first and foremost a person. However, as consumption is instrumentalised to foster competition in the internal market, we tend to forget that it is merely one dimension of our experience as a person: We are also citizens who vote, employees who produce, and netizens who interact in the online world. Even as a consumer, we have more interests than economic calculations such as health, safety, and self-organisation, which are well recognised in EU primary law (e.g., Arts. 12, 114(3) and 169(1) TFEU; Davies, 2016; Mak, 2018). The broad scope of EU consumer law further extends the identity of consumers to travellers (e.g., Karsten, 2007), residents (e.g., Domurath & Mak, 2020), energy users (e.g., Jiglau et al., 2024) and even patients (e.g., Colombi Ciacchi, & McCann, 2016). We are affected by different social and economic policies depending on the varying social roles we assume, and these multifarious capacities of our social life are well enshrined in the CFREU that protects each of us as a full person. “Consumers are market players, citizens, and participants in everyday life.” (Reisch, 2004, p. 2) The constitutional contextualisation of the consumer as a person thus emancipates consumers from the domination of the “economy” in their civil and political life. It highlights that being a consumer cannot replace our democratic rights to political participation nor monopolise our leisure time outside the consumer market.

The communitarian case equally applies to consumers: Consumer preferences are socially shaped and consumer wants are socially realised. On the one hand, consumers’ choices are not abstractly rational but should be contextualised against social, cultural, and institutional norms in their “choice architecture” (Thaler & Sunstein, 2021). The CJEU has pointed out that consumer behaviours and habits are shaped by Member States’ varying cultures and regulatory strategies and are evolving in time and space (e.g., Commission v United Kingdom [1980]; Commission v Germany [1987]; Gourmet International Products [2001]; Commission v Italy [2009]; Åklagaren v Mickelsson and Roos [2009]). Social practice theory further informs us that most of our daily consumption behaviours are highly routinised and inconspicuous, shaped—at a collective level—by the behaviours of our peers and the social setups (Beatson et al., 2020; Horta, 2018). This approach to consumer behaviours goes beyond the behavioural critique of the neoclassical economic paradigm, which primarily centres on individual cognitive biases (e.g., Ben-Shahar & Bar-Gill, 2013; Esposito, 2018; Faure & Luth, 2011), by fleshing out individualities with affective, social and cultural variables (Etzioni, 2011; Frerichs, 2011). On the other hand, consumption is socially realised. From design to manufacturing, from distribution to retail, consumption is made possible by a connected system of productive organisation and collective cooperation. Globalisation only intensifies our reliance on the global productive community, extending the supply chains to people whom we do not know (and thus do not care about). The market, where we negotiate bargains and exchange for goods, is far from a “spontaneous order” but operates on a large set of “background conditions” such as legal institutions and natural resources (Fraser, 2022; Pistor, 2019). In sum, the varied communities in which consumers are situated defy any image of an abstract, homogeneous consumer, while consumers’ dependence on these communities eludes a self-sufficient consumer. Consumers are deeply embedded into and significantly enabled by the community. It is unrealistic to view consumers as rational decision-makers free from the socialisation processes and unjust to allow some to reap the benefits of social institutions while outsourcing all externalities to those about whom “we do not care.”

The systematic categorisation of consumer protection as a “solidarity” right under the Charter suggests its strong collective and social dimension since its incorporation (Benöhr, 2013). Just as a constitutional person holds “responsibilities and duties with regard to other persons, to the human community and to future generations” (the preamble of the Charter), the embedded consumer likewise has social responsibilities regarding the consequences of her consumption for the community (on “consumer social responsibility,” e.g., Cseres, 2019; Schlaile et al., 2018). The market reading of a “responsible consumer” as someone who confidently contributes to market functioning and who is responsible for her self-care (e.g., Stănescu, 2019) should be rejected. The social responsibility of consumers resonates with the moral and ethical aspects of human behaviours such as altruism (e.g., Bowles, 2016) and pushes us to care about our fellow consumers, those whom we cannot see, and our surrounding nature. The decisions consumers make are “not necessarily based on their own narrow market-related interests only, but also on common welfare and social values” (Reisch, 2004, p. 3). This could simply mean being more conscious of the social and ecological implications of our consumption and taking our rights seriously; it could also entail refraining from unethical consumption and deploying our purchasing decisions to steer companies towards responsible practices. Of course, in light of consumers’ vulnerability, their social responsibility should also be contextual to each consumer’s circumstances so that the already disadvantaged do not bear an unjust burden.

More importantly, consumer social responsibility should not replace state obligations and corporate accountability with a moral appeal to individual consumers to behave better. Neither should individual altruism and ethical consumerism replace the debate over the common good. Recall that irresponsible behaviours result from social and institutional structures. When alternatives are inaccessible and unaffordable, blaming individuals for taking inexpensive short-haul fights serves little purpose. If the law grants consumers free and unconditional withdrawal rights, it is hardly constructive to hold them accountable for deploying these rights for their convenience, even if it comes at the expense of the environment (e.g., buy the same products in different sizes and return some). At times, consumers can even be “locked-in by circumstances,” such as the conditions of urban living and the effects of pervasive marketing, from consuming more sustainably even if they are willing to do so (Sanne, 2002). Furthermore, in a neoliberal system, the dynamics of these shaping circumstances are significantly engineered—put on steroids by law (Pistor, 2019) and subsidised by the state (e.g., Boffey, 2020; Crosson, 2019)—by powerful corporate actors. Consumers simply play along in a way over which they have little control. The powerful position of corporations also entails that the considerable costs of effecting a transition to a just, sustainable future (e.g., McKinsey Global Institute, 2022; UN News, 2023), without adequate public expenditure and effective redistributive measures, would inevitably be shifted onto consumers. It is unfair to disproportionately burden individual disadvantaged consumers, while major corporations have not only contributed to but also stand to profit greatly from existing unjust and unsustainable systems. Just like consumers, corporations that benefit from the market-enabling background conditions share, if not bear more, responsibility towards society.

Therefore, the legal responsibilisation and political empowerment of individual consumers might not be the ideal anchor for social change. The fact that consumer behaviours are institutionally shaped means that they are also adaptable through institutional and legal change; the fact that consumer vulnerabilities are socially constructed means that consumer resilience can be institutionally strengthened. As such, the desirable way forward is to publicly and democratically set up a legal, institutional, and social architecture that builds up consumer resilience and conduces to responsible consumership. It is first and foremost the task of public intervention, supported by government spending, to drive social progress beyond tinkering at the edge of the market. This task is primarily to rein in corporate power and shape socially responsible corporations to rebalance the market and social dynamics. Only thus can we democratise the social forces that shape consumer identities and fairly redistribute the social resources upon which consumers depend to satisfy their needs.

Extended Policy Implications

To reframe the consumer as a constitutional person, the state should take seriously the socialisation of individuality and the inevitability of vulnerability as a human condition. It should actively promote a social architecture that is conducive to responsible citizenship and responsible consumership. What does such an architecture look like in policy terms? In this part, I will lay out the major policy implications that flow from the image of the “embedded consumer.” Firstly, to promote and cultivate responsible consumer behaviours, EU consumer policy should take a holistic and balanced approach to protect consumers’ interests in light of other social and constitutional values. Secondly, the EU consumer protection regime should aim to address consumer vulnerability in a more systematic and coherent way. Though I focus the discussion on EU consumer policy, given the centrality of “consumer welfare” in European competition law and policy (e.g., Cseres, 2006; Daskalova, 2015; Heide-Jørgensen, Bergqvist, Neergaard, & Poulsen, 2013), the implications apply beyond consumer law.

From the Sovereign Consumer to the Responsible Consumer

EU consumer policy is underpinned by a one-dimensional, economic consumer. It reduces the consumer to her act of consumption, and consumption to price bargaining, which is not only arbitrary but undermines all other irreducible values but for self-gratification (Leczykiewicz & Weatherill, 2016, p. 12). Recall that our identity is shaped by a plurality of (competing) forces while our needs are realised by social cooperation. As such, conflicts can emerge not only between the different facets of our own identity but also between our own interests and the interests of the community. To sustain the organic solidarity that enables consumption, the “embedded consumer” requires EU consumer policy to promote consumer social responsibility by holistically balancing the pluralistic, sometimes conflicting, interests involved, not only between the various rights of the consumer as a person but also between consumer rights and community interests. Of course, this is not to say that the balancing exercise should be conducted in each and every consumer case (e.g., due to the uncertainty risks of such an approach; Reich, 2013), nor does it suggest that all private disputes should be elevated to constitutional disputes. Instead, it is rather a plea for more balanced and systematic thinking in consumer policy-making and implementation.

This balancing approach is familiar to EU fundamental rights law. It has been a long tradition that fundamental rights are not absolute but must be considered in relation to their social function (e.g., Wachauf [1989], para. 18). Under Art. 52(1) CFREU, limitations on fundamental rights may be imposed—in accordance with “the principle of proportionality”—if they are necessary to protect “the rights and freedoms of others” or the “general interest recognised by the Union.” The community is thus a significant (source of) value in the balancing exercise (Crowder, 2006). Besides justifying limitations on one specific fundamental right, the CJEU has also mobilised the balancing approach to solving conflicts between competing fundamental rights inter se (e.g., Promusicae [2008], para. 68; Scarlet Extended [2011], para. 44; Sky Österreich [2013], para. 60; WABE [2021], para. 84). The CJEU more often than not refrains from conducting substantive balancing exercises in specific cases and instead proposes a “coordinating principle” as a guideline, which allows the CJEU to express the Union’s conception of the common good while leaving the ultimate contextual balancing to national courts (Mak, 2013). For example, in Google Spain, a conflict arises between the general public’s freedom to publish and access information about an individual (Art. 11 CFREU) and the individual’s right to privacy and data protection (Arts. 8 and 9). The CJEU ruled that while the individual’s right in principle overrides the general public’s freedom of information, a balance is required accounting for factors like the nature of the information and the public role of the individual so that the interest of the general public is also involved. Besides the judiciary, EU legislators are also becoming more conscious of the conflicting interests in designing legal measures (e.g., Art. 85 of the General Data Protection Regulation 2016). The balancing approach is also central to sustainable development.Footnote 3 In general, it represents a constitutional vision of “struggles” in the broader political and democratic process of social change. It calls for conscious navigation of conflicts and trade-offs between the market, the social, and the environment to achieve a balanced transition.

Apply such balanced thinking to consumer policy. On the one hand, consumption inevitably becomes entangled with other non-economic, social values—some expressed as fundamental rights—such as health and safety in consuming products and data security and freedom of expression in using social media services. Viewing the consumer as a person thus necessitates the protection of not only the economic but also the non-economic aspects of consumers’ experience. One crucial point is regulatory coherence. Sectoral, compartmentalised legislation in EU law results in unnecessary fragmentation and inconsistent outcomes in consumer protection. It could be uncoordinated protection of the various interests of the same consumer. For example, the regulation of consumer goods is scattered across product (safety) regulation, consumer sales law, and waste regulation, with insufficient coordination (Maitre-Ekern, 2014). It could also be inconsistent protection of the same interest. Think of the uneven recoverability of non-economic loss under EU law (Havu, 2019). A coherent, holistic approach is thus desirable to better protect the consumer as a person. There are already attempts at coherence such as the interaction between public product safety standards and private tort claims (e.g., Spindler, 2009; QB v Mercedes-Benz Group AG [2023]) as well as coordination between data protection law and consumer contracts (e.g., Recital 48 of the Digital Content and Digital Services Directive 2019). Courts have also tried to safeguard values like freedom of expression (BGH judgments of 27 January 2022, III ZR 3/21 and III ZR 4/21; Grochowski, 2023) and the right to housing (Aziz [2013]; Rutgers, 2017) through unfair terms control.

On the other hand, consumer protection is not absolute but should be balanced against other values (e.g., E. Friz [2010, para. 44; Gonzlez Alonso [2012], para 27; Hamilton [2008], paras. 39–40). In fact, consumer protection, in its current economic form, could easily contradict the interests of the community and its other members. It inevitably puts constraints on the traders’ freedom to conduct business. Consumers’ right to a good bargain could be in tension with workers’ rights to fair wages and just working conditions. The unfettered freedom of consumer choice can foster overconsumption with grave implications for the environment. Responsible consumership accounts for the impact of consumption on the community. Regulatory coherence is helpful in this regard as well. Responsibilisation of individual consumers is another route (Micklitz, 2019). For example, to counterbalance the negative environmental impact of consumption, we can consider taking away consumers’ withdrawal rights in case of misuse,Footnote 4 as well as consider charges for disposable products or require deposits for returnable containers (see, generally, De Almeida & Esposito, 2023). However, the costs and distributive implications of these approaches for individual consumers cannot be overlooked. This means that individual responsibilisation is only fair and effective when coupled with institutional changes, such as obligating businesses to offer (free or affordable) reusable alternatives or building accessible recycling points.

Ultimately, tinkering with individuals is insufficient to bring about fundamental changes. The balanced approach has more crucial institutional implications for the EU. The EU should foster dialogues and coordination among its institutions and internal departments (such as the different Directorates-General of the European Commission and the Committees of the European Parliament), on the one hand, and between European and national institutions, on the other. The CJEU should promote the constitutional reading of consumer acquis by providing coordinating principles to highlight the common good dimension in consumer adjudication flowing from the Charter. The legislators are also mandated to more consciously navigate the diverse interests affected by consumer legislation, as opposed to pivoting on a reductive approach to internal market building. Recall Art. 3 TEU—the “social market economy” is more than economic efficiency. Similar to how the EU judiciary merely offers coordinating principles but not the final resolution of any given case, legislators should also caution against the use of maximum harmonisation in consumer legislation which disregards national context and excludes local experimentation (Terryn, 2023). Context matters in balancing. To give a concrete example, in light of the urgency and the cross-boundary nature of the climate crisis, EU legislators should carefully (re)assess the environmental impact of consumer legislation and incorporate the results into legislative proposals and coordination initiatives. The judiciary should promote an eco-friendly interpretation of consumer acquis by indicating that Art. 11 TFEU should be taken more seriously in consumer disputes and other private disputes and that environmental protection should have a pronounced weight in the balancing exercise.

From the Average Consumer to the Vulnerable Consumer

Vulnerability is a human condition that individuals can hardly escape. Such universality of vulnerability reflects the insufficiency of the restrictive, exceptional, and static approach to consumer vulnerability in EU law. Instead, policy should adopt a responsive, dynamic, and contextual approach to effectively protect all consumers (similarly, Waddington, 2013). Consumer vulnerability should be regarded as the cornerstone of EU consumer policy—both in a positive and normative sense (similarly, Domurath, 2013). Positively, in particular in the context of the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive, rather than assessing the impact of commercial practices on a “reasonably well-informed and reasonably observant and circumspect” average consumer, it is proposed that evaluation should centre on “the general impression that [the relevant practice] is likely to convey to a credulous and inexperienced consumer.”Footnote 5 In other words, the average consumer is rather vulnerable. This is not a juridical diagnosis implying that all consumers are incompetent but rather a democratic prescription that firms should recognise the embeddedness of consumer behaviours and adjust their treatment accordingly. By embracing such a benchmark, the law acknowledges that cognitive biases cannot be completely overcome by learning and that social practices cannot always be overwritten by abstract rationality. In fact, the CJEU has deviated from the average consumer benchmark in several cases (e.g., Canal Digital Denmark [2017]; mBank [2023]; Teekanne [2016]),Footnote 6 while national policymakers have been making use of the “targeted average consumer” to overcome the limited scope of consumer vulnerability under EU law (Šajn, 2021).Footnote 7 A recognition of the general vulnerability of the average consumer does not obviate the need to broaden the definition of particularly vulnerable consumers, both due to their socio-demographic and behavioural characteristics as well as personal situations (European Commission, 2016). Taking a step further, a constitutionally informed consumer policy should also take into account the implication of factors such as race and ethnic background for consumer experiences (Hesselink, 2023).

At a more fundamental level, the vulnerable position of consumers is inherent in and inseparable from the very context that defines consumers’ identity: the market. In a normative sense, consumer vulnerability is an evolving concept tied to “lopsided commercial relationships that are continuously, dynamically, and strategically adapted by firms to make consumers more suggestible and exploitable” (Becher & Dadush, 2021, p. 1587). In the online marketplace, especially, a structural digital “choice architecture” continuously feeds traders with consumers’ data, deepens their information asymmetries and magnifies their power imbalance (Helberger et al., 2021; Helberger et al., 2022). Digital manipulation is increasingly done in a personalised manner and targets personalised vulnerability (Strycharz & Duivenvoorde, 2021). As consumers become increasingly intertwined with the market, consumer vulnerabilities are not only exploited but also actively created by firms, using, for example, biased algorithms that perpetuate existing discrimination (e.g., Grochowski, Jabłonowska, Lagioia & Sartor, 2022) or advertising practices that normalise undesirable behaviour patterns (e.g., Kaupa, 2021). Consumers with such institutional situatedness rarely act on information but just go with the flow set by firms. Despite some of their efforts to go against the flow, these conscious consumers find themselves locked in old patterns (Sanne, 2002). Information-based tools do have their merits (e.g., Luzak et al., 2023; Tigelaar, 2019), but they do not alter the fundamental reality that, even armed with sufficient and correct information, consumers cannot overcome the structural vulnerabilities that define their experience. A more substantivist approach to consumer protection is thus desirable (similarly, Herrine, 2022; Howells, 2005).

A substantivist approach starts from consumers’ situatedness in the (digital) market infrastructure when designing consumer law, aiming to foster just commercial structures by design and by default. It moves away from sole reliance on information disclosure but zooms in on the direct quality control of goods and services; it aims to not only repair but also prevent consumer harm. I will further illustrate three points. First, similar to how product safety regulation excludes unsafe products from the market, consumer law should further aim to make sustainable and ethical products the market norm. Alignment with fundamental rights protection entails that, for example, outright prohibition of child labour (Art. 32 CFREU) mandates the removal of products using child labour from the consumer market (Study Group on Social Justice in European Private Law, 2004, p. 668). Price fairness of products should not be indiscriminately excluded from consumer regulation as it is core to consumers’ financial vulnerability.Footnote 8 Second, (digital) services and (data-driven) commercial practices should also be ethically and sustainably designed (European Parliament, 2023). Policy should recognise and regulate their impact on shaping consumer habits and behaviours, such as the normalising effect of advertising (e.g., Kaupa, 2021), and their potential harm to mental health (e.g., Palka, 2021), in order to democratically reclaim control over those identity-shaping forces. Instead of merely disclosing harmful practices, they should be blacklisted. Third, a substantivist approach is at the same time a contextualised and balanced one. Substantive equality among consumers means that consumers with different levels of vulnerability should be treated differently to a justifiable extent. Consumer law should not disregard the differentiated—or even personalised (Ben-Shahar & Porat, 2021)—needs for protection among consumers based on the impact of market structure on their unique bodies and experiences. As discussed earlier, regulatory intervention should go hand in hand with redistributive measures to ensure a fair distribution of the resulting costs among consumers, businesses, and the society at large. In particular, for those consumers who simply cannot participate in the market due to poverty or other similar circumstances, direct state transfers—as opposed to ever more market empowerment tools—should be made to address their vulnerabilities outside the consumer market.

Vulnerability is part of the collective identity of consumers. Collective vulnerability calls for collective response. Providing consumers with more robust, more substantive protective tools does not mean that it is entirely up to individual, vulnerable consumers to effectively seek redress against market risks and manipulations (e.g., Scott, 2019). Instead, public bodies and consumer organisations should take up the task of defending vulnerable consumers in a collective manner and push for a fairer infrastructure.Footnote 9 Art. 47 CFREU mandates effective protection from the judiciary. In fact, it has already been invoked by the CJEU—in conjunction with other substantive Charter provisions or secondary EU law—to confirm Member States’ obligation to effectively implement EU law (e.g., Kušionová [2014], Mak, 2014; Sánchez Morcillo & Abril García [2014]). The ex officio application of several areas of EU consumer protection (e.g., Radlinger and Radlingerová [2016], para. 62) also indicates that the judiciary institutionally starts from an image of vulnerable consumers. Besides judicial protection, given the prominence of administrative enforcement of EU consumer law, Art. 41 on the right to good administration should be mobilised and broadly interpreted to ensure the procedural guarantees of administrative proceedings (e.g., Cafaggi, 2022). Last but not least, consumer organisation plays a vital role in defending consumer interests, shaping consumer policies, and enforcing consumer protection. The freedom of association (Art. 12 CFREU) and the principle of democracy require the state to provide an institutional framework where consumer organisations can meaningfully contribute to the democratisation of consumer policy. This can further catalyse bottom-up consumer activism, fostering increased consumer participation and engagement in various forms of community life—local and transnational, economic and political, social and cultural, intragenerational and intergenerational—that together shape their “habits of the heart” (Bellah, 1986).

A Transformation Underway? Taking Stock of European Consumer Policy

In this part, I will pit the most recent development in EU consumer policy against the “embedded consumer” benchmark. I will first examine the “New Consumer Agenda” for 2020–2025 (“Agenda” or “New Agenda”), which offers a more systematic view of the future directions of EU consumer policy, before moving on to a more specific example, namely the Commission proposal for the Right to Repair Directive 2023. The analysis here is by no means exhaustive, but it intends to show how the “embedded consumer” can in practice be translated into legal and policy terms.

New Consumer Policy

In 2020, the Commission adopted the New Agenda entitled “Strengthening Consumer Resilience for Sustainable Recovery,” laying out the strategy for EU consumer policy from 2020 to 2025. As a starting point, the New Agenda takes “a holistic approach” to address consumer protection and other EU policies—and the other policies are not exclusively limited to the internal market in the traditional sense but also those related to the green and digital transition (European Commission, 2020, pp. 1–2).Footnote 10 It reflects on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on consumer protection and proposes five key priority areas for future EU consumer policy: the green transition; the digital transformation; redress and enforcement of consumer rights; specific needs of certain consumer groups; and international cooperation. To what extent does the New Agenda align with the “embedded consumer” by taking balancing and vulnerability seriously?

First, the Agenda draws closer attention to (the need for) a more pluralistic and balanced view of consumer protection. The pandemic proves that essential products and services are crucial to safeguard various consumer interests regarding “fundamental rights, medical ethics, privacy, and data protection” (European Commission, 2020, pp. 2–3). In light of the green transition, consumer interests must be aligned with environmental protection (European Commission, 2020, pp. 6–9). Notably, the Sustainable Products Initiative aims to “make sustainable products the norm” (European Commission, 2020, p. 6). In light of digitalisation, consumer protection should be coordinated with the need for privacy and data protection, as well as technological development (European Commission, 2020, pp. 10–14). Second, addressing consumer vulnerability and building consumer resilience is central to the New Agenda. The scope of consumer vulnerability is broadened to cover both personal and situational vulnerability (European Commission, 2020, p. 16).Footnote 11 It is also both universal and particular. While profound social disruption like the pandemic and the digital transformation has a bearing on everyone, it has particularly exacerbated some forms of vulnerability for the elderly and people with disabilities. Biased algorithms perpetuated “pre-existing cultural or social expectations,” while the exploitation of cognitive biases of consumers could “affect virtually all consumers” (European Commission, 2020, p. 18). Financial vulnerability is also taken into account, highlighting the importance of “[a]ffordability […] to ensuring access to products and services for low-income consumers” (European Commission, 2020, p. 17).

However, the Agenda hardly moves away from the information paradigm and individual responsibility and remains cautious about substantive intervention (Terryn, 2021). It starts by asserting that the empowered consumers expect “to make informed choices and play an active role in the green and digital transition” (European Commission, 2020, p. 1). In the context of the green transition, though substantive measures do exist, such as fighting planned obsolescence by imposing product standards, the Commission sees the EU’s main role as to “unlock the potential” of consumers” “growing interest in contributing personally” to sustainability (European Commission, 2020, p. 5). It is acknowledged that “profound and rapid change in [consumers’] habits and behaviour to reduce [the] environmental footprint” is required for the green transition (European Commission, 2020, p. 5). Yet, the Commission cautions against “imposing a specific lifestyle” (European Commission, 2020, p. 5), without fully acknowledging, let alone challenging, how consumers’ unsustainable habits and behaviours have already been imposed by corporate practices and social infrastructure. The New Agenda is still largely working with a market imaginary—simply with a switch in focus from a traditional market to a digital and green market.

We can thus indeed see a vague profile of the “embedded consumer” being born in EU consumer policy, though a public approach to a responsible consumer policy is largely missing while the declaration of “a holistic approach” to breaking silo thinking has not (yet) penetrated all areas (Terryn, 2021). A myriad of legislative proposals are working their way through the EU legislative procedure (e.g., proposals for Ecodesign Regulation 2022, Empowering Consumers in the Green Transition Directive 2022; Right to Repair Directive 2023; Green Claims Directive 2023), but it is unclear what results will come out of the interaction between interest group lobbying, public momentum and the political will of EU institutions and Member States to bring about a fundamental change. None of this renders the Agenda less significant, however, for it clearly signals a holistic vision of embedding consumer law into other fields of EU initiatives that together shape the EU’s future outlook.Footnote 12 Making visible this broader vision is crucial in transforming European consumer law. This is because it is not always the technical rules per se but rather the underlying, unspoken socio-economic imaginary that stands in the way of a more fundamental change. And vice versa—without engaging in a serious discussion about the ratio legis and societal setting of consumer protection, merely tinkering with ad hoc fixes will hardly do the trick (Bartl, 2020).

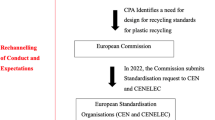

Example: Right to Repair

As part of the action plan announced in the New Agenda, the Commission put the proposal for the Right to Repair Directive (“RRD”) on the table in early 2023.Footnote 13 The proposal juxtaposes the objectives of internal market functioning and a high level of consumer and environmental protection (Art. 1 RRD). It presents a rather balanced view of the various interests involved: companies’ freedom to conduct business (Art. 16 CFREU), consumer protection (Art. 38 CFREU), and environmental protection (Art. 37 CFREU) (RRD explanatory text, p. 8). It is also balanced in the sense that it coordinates various regulatory regimes that together shape the lifecycle of consumer goods in the market: The scope of the RRD aligns with EU product regulation (design and production phase) and it also complements commercial practices regulation (purchase phase) and consumer sales law (after-sale) (European Parliament resolution, 2022). Outside the legal guarantee provided by the Sale of Goods Directive 2019, consumers still have a right to request repair from the producers in line with the repairability requirements set out by certain product regulations (Art. 5 RRD). Within the legal guarantee, however, consumers actually have a responsibility to prioritise repair over replacement as they no longer have the freedom to choose contractual remedies granted by Art. 13 of the Sale of Goods Directive 2019 (Art. 12 RRD). This approach provides an intriguing example of the legal responsibilisation of consumers to promote responsible consumership. The individual responsibilisation is further supported by architectural changes, such as Member States’ obligation to introduce online matchmaking repair platforms to facilitate repair (Art. 7 RRD).

However, the balanced approach and the vulnerability approach do not consistently penetrate the proposal. Though it does mention the need to ensure accessibility for vulnerable consumers, especially people with disabilities (e.g., Art. 7(1)(f) RRD), the proposal fails to place vulnerability at its core. Largely relying on bureaucratic information disclosure and comparability (e.g., the European Repair Information Form introduced by Art. 3 RRD), the approach taken is insufficiently substantivist. Moreover, the accessibility and affordability of repair services and spare parts are missing, rendering the declared regulatory attention to consumers’ financial vulnerability in the New Agenda illusory. Neither is the proposal as coordinated and balanced. The scope of the RRD is rather limited and does not align with the general ecodesign regulation (e.g., the proposal for Ecodesign Regulation 2022). The connection with sales law could have been more consistent by making durability and repairability an objective conformity requirement under the Sale of Goods Directive 2019. Moreover, the proposal primarily revolves around repair by sellers or producers and pays little heed to repair by independent repairers and by consumers themselves, although the latter scenarios face the most legal obstacles. For example, what does it mean for consumers’ contractual warranty if they repair themselves or go to local independent repairers? What are the IP law and competition law implications for independent repairers, particularly given that producers are obligated to ensure “access to spare parts and repair-related information and tools” under Art. 5(3) RRD?

It is also clear that market logic dominates the proposal, highlighting the benefits of “increased employment, investment, and competition in the EU repair sector in the internal market” (RRD explanatory text, p. 8), making environmental protection a goal only in passing. Interestingly, the proposal recognises that the promotion of repair may induce losses in business revenues due to “forgone sales and reduced production of new goods,” but these losses are transferred to consumer welfare, especially given that consumers may reinvest the saved money into the overall economy to boost growth and investment (RRD explanatory text, p. 8). With such a presumed attitude of consumers, it is hard to imagine how repair can truly contribute to sustainability. Last but not least, all of these shortcomings give away the fact that the EU still envisages its role, as well as that of the Member States, as facilitative to the market. As opposed to imposing substantive and mandatory standards, the Commission merely aims to promote the voluntary European quality standard (Recital 27 RRD); as opposed to spending on promoting the set-up of more repair centres, Member States are merely expected to provide matchmaking services. The rest is up to market and competition.

Conclusion

Eclipsed by the internal market project, the economic rationale permeates European consumer policy. The image of European consumers is legally engineered to conform to the neoliberal prototype of market actors. As analysed in this article, this image is not only reductive but also unwholesome, as consumption is inextricably interwoven with social justice, sustainability, and other urgent items on our transformative social agenda. Such interconnectedness conveys the imperative for a holistic approach to re-embed consumers and consumer policy into the broader vision of a just and sustainable collective future enshrined in EU primary law, especially the Charter. This article proposes the “embedded consumer” benchmark that realigns European consumer policy with the Charter to ensure that a constitutional person is not reduced to a mere “homo economicus” consumer.

Under the Charter, a constitutional person is fundamentally shaped and significantly enabled by their communities and thus bears “duties and responsibilities” towards the community. This obligation does not always amount to legal responsibility as individuals are inevitably vulnerable under unfair social structures and rely on social institutions to build up their resilience. Accordingly, the embedded consumer is also socially responsible and humanly vulnerable. This entails that a responsible framework of consumer policy should move beyond individual responsibilisation and involve public obligations and corporate responsibilities to create a framework conducive to sustainable and responsible consumption. More specifically, a responsible framework is a balanced framework, which consciously navigates the conflicts not only between the various rights of the consumer as a person but also between the rights of the consumer and the interests of the community. Regulatory coordination is crucial in this regard. A responsible framework also takes consumer vulnerability as the starting point for consumer policy, which requires more substantivist intervention to protect consumer interests.

Ultimately, it is about changing our habits of the heart, not only individual behaviours but also the collective ethos of our community. For centuries, consumption—which carries the connotation of “wasting,” “using up,” and “finishing” and embodies a linear mode of material consumption—has been regarded rather negatively (Trentmann, 2016). It was only in the late seventeenth century that economists began to sanctify consumption as a way to satisfy individual wants and increase national wealth (Trentmann, 2016). What we view as normal today—more, cheaper, and new mean better—was not always normal. In this light, raising consumer awareness through consumer education is a practical yet pivotal first step to re-embed consumers into our collective future (e.g., McGregor, 1999). The identity of consumers came out of a history of collective struggles—we used to unite together to fight for our rights (Trentmann, 2016). We should retake that power and claim our collective identity as constitutionally, socially, and ecologically embedded consumers. Instead of “wasting,” we can create a circular setting; instead of “using up,” we can use again and again; instead of “finishing,” we can save and share. It is not always normal that more, cheaper and new would mean better. Our wants and needs change, as and when our values do. Normality changes too, as and when we seriously reflect upon what normality should entail in our collective future.

Notes

The concept of “embeddedness” was pioneered by Karl Polanyi (1957) and has since become a central concept of economic sociology and other fields. In this article, embeddedness broadly refers to the interplay between social phenomena (here, consumption) and the different conditions within which those phenomena take place and upon which they depend., though this article does not rely on the literature on embeddedness.

Art. 11 TFEU provide: ‘Environmental protection requirements must be integrated into the definition and implementation of the Union’s policies and activities, in particular with a view to promoting sustainable development.’ See Wasmeier (2001); Krämer (2012); Sjåfjell and Wiesbrock (2017); Kingston (2015); Nowag (2016).

The European Commission (2009) defines sustainable development as “a framework for a long-term vision of sustainability in which economic growth, social cohesion and environmental protection go hand in hand and are mutually supporting.”.

For example, in the Commission’s proposal for a Directive as regards better enforcement and modernisation of EU consumer protection rules (2018), there was an (unsuccessful) attempt to add an exception to withdrawal right, which provides that consumers are not entitled to withdrawal as regards ‘the supply of goods that the consumer has handled, during the right of withdrawal period, other than what is necessary to establish the nature, characteristics and functioning of the goods’.

In his Opinion on a recent request for a preliminary ruling on the benchmark of the “avergae consumer,” Advocate General Emiliou (Compass Banca SpA [2024]) has already voiced that the benchmark should not be understood by mere reference to “homo economicus,” but should rather take into account other theories which show the need for greater consumer protection, such as the behavioural input of “bounded rationality.”.

Note that the vulnerability approach taken in specific sectors like financial services (especially the discussion of responsible lending), energy (especially the discussion of energy poverty) and other universal services is not considered here, where the notion of vulnerability already assumes a more prominent policy weight.

Price fairness, as the core of economic calculation in consumers’ (presumed) decision-making processes, largely eludes the scope of European consumer law, except for price transparency. For example, the fairness of price adequacy is in principle excluded under Art. 4(2) of the Unfair Terms Directive (1993). However, according to the CJEU, a lack of transparency can open the gate of judicial price control within the scope of the said Directive (e.g., D.V. v M.A. [2023]).

As noted earlier, this should ideally be supported by public expenditure. Yet, the harsh reality is that there has been a reduction in public investment in such public bodies as well as in subsidies available to consumer organisations, largely due to fiscal austerity measures. Such spending, which may not always be the primary focus for governments at the best of times, has become even less of a priority amid the tight constraints of public finances exacerbated by the post-pandemic fallout and during an ongoing series of energy, security, immigration and budgetary crises. As such, this issue is symptomatic of a broader problem stemming from neoliberal state policies.

‘[The Agenda] complements other EU initiatives, such as the European Green Deal, the Circular Economy Action Plan and the Communication on Shaping Europe’s digital future. It also supports relevant international frameworks, such as the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.’.

“The vulnerability of consumers can be driven by social circumstances or because of particular characteristics of individual consumers or groups of consumers, such as their age, gender, health, digital literacy, numeracy or financial situation.”.

While new legislative developments have transpired since then, the focus here is on the text of the Commission’s original proposal.

References

Alexander, G. S. (2018). Property and human flourishing. Oxford University Press.

Bartl, M. (2015). Internal market rationality, private law and the direction of the union: Resuscitating the market as the object of the political. European Law Journal, 21(5), 572–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12122

Bartl, M. (2020). Socio-economic imaginaries and European private law. In P. F. Kjaer (Ed.), The law of political economy: Transformation in the function of law (pp. 228–253). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108675635.009

Beatson, A., Gottlieb, U., & Pleming, K. (2020). Green consumption practices for sustainability: An exploration through social practice theory. Journal of Social Marketing, 10(2), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSOCM-07-2019-0102

Becher, S., & Dadush, S. (2021). Relationship as product: Transacting in the age of loneliness. University of Illinois Law Review, 2021(5), 1547. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3590786

Bellah, R. N. (1986). Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life. Harper & Row.

Benöhr, I. (2013). EU consumer law and human rights. Oxford University Press.