Abstract

There have been seven qualified health claims (QHCs) in the marketplace about the relationship between the consumption of green tea and the reduced risk of breast and/or prostate cancers that were written by three stakeholders (the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Fleminger, Inc. (tea company), and the Federal Court). This paper evaluates assertions about the effects of these claims on consumers, which were contested in a federal lawsuit. Using a 2 × 7 experimental design, 1,335 Americans 55 years and older were randomized to view one QHC about green tea and cancer, or an identical QHC about a novel diet-disease relationship; yukichi fruit juice and gastrocoridalis. The results show that differing stakeholder descriptions of the same evidence significantly affected consumer perceptions. For example, QHCs written by Fleminger, Inc. were rated as providing greater evidence for the green tea-cancer claim. An FDA summary statement implied mandatory (vs. voluntary) labelling and greater effectiveness, and qualitative descriptions suggested that greater evidence existed for the claims (vs. quantitative descriptions). Greater evidence was also inferred for familiar claims (green tea and cancer).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Health claims commonly found on food and supplement labels are intended to highlight a dietary component (such as calcium) that may reduce the risk of disease or ill health (like osteoporosis). These claims are founded on “significant scientific agreement” (SSA), a consensus among qualified experts that the preponderance of the available scientific evidence supports the existence of a diet-disease relationship (Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act 1938; Ippolito and Mathios 1993, pp. 188-205).

However, many of the diet-disease relationships that companies wish to promote are based on limited or inconclusive scientific evidence that falls short of the SSA standard. For example, there is limited scientific evidence behind the link between eating whole grains and a reduction in the risk of type 2 diabetes, consuming corn oil and reductions in the risk of heart disease, and drinking green tea and reductions in breast and prostate cancer.

The legality of the use of these claims was established as the result of a seminal lawsuit (Pearson vs. Shalala 1999) brought by dietary supplement marketers hoping to bolster sales of their products. The Court ruled that companies could market food and dietary supplement products using health claims that do not meet SSA standards if those claims are accompanied by “well-drafted disclaimers” that would prevent consumers from being misled about the amount or certainty of the evidence supporting the diet-disease relationship.

These Qualified health claims (QHC) are required to encompass a statement summarizing the scientific evidence for customers to evaluate (Government Accountability Office 2011). This disclaimer has been a significant source of contention among stakeholders. Much of the disagreement is about how to clearly and accurately communicate the level of scientific certainty regarding a particular diet-disease relationship when the evidence is emerging, incomplete, or inconsistent. The food and dietary supplement industries want to maximize the marketing value of these claims to increase product sales. Effective claims can make a product more competitive by differentiating it from others in the same category, leading to greater profits (Emord and Schwitters 2012, pp. 1-12; Ippolito and Mathios 1993, pp. 188-205; Pearson vs. Shalala 1999). Companies argue that consumers may benefit from knowing that some evidence exists for the diet-disease relationship, even if that evidence is limited or inconclusive. Therefore, the goal of the food and supplement industries is for the evidence to be described accurately, yet in the most favourable way, so that consumers focus on the potential health benefits of their products. Consequently, when companies believe a description of evidence is unfavourable, they are willing to take the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to court to change it (Berhaupt-Glickstein et al. 2014, pp. 62-70). In contrast, the FDA, which regulates QHCs, insists that the disclaimers accurately characterize the quantity and strength of the evidence behind a diet-disease relationship, so that consumers are protected from potentially deceptive marketing (Berhaupt-Glickstein et al. 2014, pp. 62-70). The Court’s interest in QHCs is to support First Amendment rights for the food and supplement industry, as well as to support the federal government in protecting the public’s health through the least restrictive means necessary (Pearson vs. Shalala 1999).

This tension among stakeholder goals is illustrated by the evolution of the QHC regarding the relationship between green tea and its potential to reduce the risk of breast and prostate cancers. There have been seven QHCs in the marketplace about green tea since 2004. Significantly, the scientific evidence evaluated by the FDA for this diet-disease relationship has not changed over time. Instead, these iterations of the green tea claim are the result of an escalating dispute between a green tea manufacturer, Fleminger, Inc. (Fleminger) and the FDA, which led to a federal lawsuit that was decided in 2012 (Fleminger, Inc. v. U.S. Department of Health, and Human Services 2012).

The arguments made in the case, and its outcome, have significantly influenced how QHCs are currently written and enforced. Significantly, the lawsuit hinged on presumed flaws in the disclaimer language of the disputed QHCs to accurately convey to consumers the level of scientific evidence supporting the link between drinking green tea and reductions in breast and/or prostate cancer. However, the assumptions regarding public understanding of the disputed QHCs were not grounded in existing empirical consumer research, nor was the resulting QHC that the Court suggested as a potential remedy. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to test the assertions made by the parties about the green tea QHCs leading up to the 2011 lawsuit, as well as arguments from the Court proceedings.

To put the green tea QHCs and the dispute into context, we first give an overview of the health claim system. We then provide a background of the evolving green tea QHCs and elaborate on stakeholders’ assertions about consumer understanding of those claims.

Regulation of Qualified Health Claims

The FDA regulates health claims under the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act 1990 (Wong et al. 2015, pp. 540-551). Companies first petition the agency to use a new health claim on a productFootnote 1 (Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs 2015). The agency reviews the scientific literature about the diet-disease relationship and will authorize a health claim if the evidence meets SSA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2013). The FDA writes model health claim(s) for authorized diet-disease relationships that meet SSA and posts them on the agency website for companies to use. Companies may choose to write their own claims so long as they meet technical requirements about nutrient levels, language (i.e., “may” or “might”), and the nature of the product (U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2013). There are twelve health claims supported by SSA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2013).

In addition, there are more than 30 diet-disease relationships that do not meet the SSA standard but are partially supported by evidence. In these circumstances, the FDA permits companies to use a QHC (Pearson vs. Shalala 1999). The agency prescribes the language for QHCs to ensure the description of evidence for the claimed relationship is scientifically accurate and does not mislead consumers (U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2011c).

Originally, the strength of evidence behind a health claim was indicated using a letter-grade system (U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2003). Health claims supported by SSA were assigned an A-grade, representing a “high level of comfort” among scientists that a particular diet-disease relationship exists (Federal Trade Commission 2006; U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2003). Qualified health claims were assigned evidence grades of B, C, or D. B-grades indicated a “moderate or good level of comfort” among scientists about the claimed relationship, a C-grade represented a “low level of comfort,” and a D-grade, a “very low level of comfort” (Berhaupt-Glickstein and Hallman 2017, pp. 2811-2824; Food and Drug Administration 2003). However, the grading system was abandoned in 2009Footnote 2 when research demonstrated that consumers found the grades confusing (U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2011c; Hasler 2008, pp. 1216S-1220S). Instead, each QHC now includes a written disclaimer that summarizes the evidence for the claimed relationship without the inclusion of an evidence grade. It is disputes over the language in this disclaimer that has driven litigation involving QHCs. The FDA writes all QHCs to ensure they accurately characterize the evidence for a claimed relationship. The agency enforces QHCs by monitoring claims on products since any deviation from the prescribed language is unlawful (U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2011d). The intention is to properly label products so that consumers are protected “from misleading claims…about health benefits that are not supported by science” (U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2011a).

Research About QHCs

Research demonstrates that consumers are confused by QHCs. Consumer studies have tested different formats to measure the clarity of messages designed to communicate the level of scientific evidence in QHCs. Some studies have tested graphic formats that include or do not include a grade of evidence (i.e., A, B, C, D) (Derby and Levy 2005, pp. 1-41; Fitzgerald Bone et al. 2012, pp. 132-133; U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2009; Hooker and Teratanavat 2008, pp. 160-176; Kim et al. 2010, pp. 428-432; Reinhardt-Kapsak et al. 2008, pp. 248-256). Other studies have examined text-only claims, also with and without reference to an evidence grade (Derby and Levy 2005, pp. 1-41; Fitzgerald Bone et al. 2012, pp. 132-133; U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2009; U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2011b; Hooker and Teratanavat 2008, pp. 160-176; Kim et al. 2010, pp. 428-432; Reinhardt-Kapsak et al. 2008, pp. 248-256). Yet, regardless of the format tested, consumers were unable to identify the level of evidence meant to be communicated in the QHC (Derby and Levy 2005, pp. 1-41; U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2009; Hooker and Teratanavat 2008, pp. 160-176; Reinhardt-Kapsak et al. 2008, pp. 248-256).

However, two studies have shown that when consumers viewed a QHC supported by a D-grade, they recognized that the level of evidence was quite low. In one study, consumers accurately rated the strength of evidence using a 7-point scale (1 = very uncertain; 7 = very certain) for two green tea QHCs that represented a D-grade of evidence (see Table 1, rows FDA_05b and FDA_05p) (Derby and Levy 2005, pp. 1-41; U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2009). In another study, consumers had appropriately low confidence in the scientific support for a diet-disease relationship when they observed a QHC that represented a D-grade for the claimed relationship (Hooker and Teratanavat 2008, pp. 160-176).

Qualified Health Claims About Green Tea and Cancer

The case for the relationship between green tea consumption and reduced risk of breast or prostate cancer was originally assigned the lowest level of evidence (a D-grade) by the FDA (2012). The supporting evidence reviewed by the FDA has remained unchanged over the past 16 years. Yet, the claim language and description of evidence have changed seven times. The green tea QHC has changed as the result of lawsuits (Berhaupt-Glickstein et al. 2014, pp. 62-70) illustrating the difficulty of balancing scientific accuracy and safety with the Commercial Speech freedom of companies, along with the right of consumers to have access to imperfect or emerging evidence that does not meet the SSA standard. These claims are referenced in this paper using the author of the claim (Fleminger, the FDA, or the Court) and the year it appeared, as shown in Table 1.

The claims authored by Fleminger and the FDA differ in how they characterize the scientific evidence. The original claim proposed by Fleminger in 2004 was rejected by the FDA, which argued that the claim mischaracterized the evidence for the diet-disease relationship, and so would be misleading to consumers (Flem_04).

In 2005, the FDA wrote and began enforcement of separate QHCs describing the relationship between drinking green tea and breast cancer (FDA_05b) and between drinking green tea and prostate cancer (FDA_05p). These two QHCs use disclaimers using a format that we term mixed model because they both identify the number of studies about the diet-disease relationship evaluated by the FDA and describe the strength or quality of the studies (Berhaupt-Glickstein and Hallman 2017). In contrast, qualitative disclaimers describe the level of evidence, but do not quantify the number of studies involved (see Table 1). These QHCs also include an “FDA summary statement” (i.e., FDA concludes...) meant to signal the FDA’s position on the diet-disease relationship.

Fleminger asserted that the descriptions of evidence written by the FDA in 2005 (which resulted in QHCs of more than 50 words each) were overly technical and potentially confusing to consumers. They are no longer enforced by the FDA because they use language similar to that of claims found by the Court to be too restrictive (Alliance for Natural Health U.S. v. Sebelius 2010; Berhaupt-Glickstein et al. 2014, pp. 62-70; U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2009).

Dissatisfied with the FDA’s QHCs, Fleminger posted a QHC to its website in 2008 stating that there is “credible evidence” supporting the claim that green tea may reduce the risk of breast and prostate cancers (Flem_08). Two years later, it mimicked an FDA summary statement by adding the phrase “The FDA has concluded,” to its statement, “there is credible evidence supporting this claim.”

The dispute peaked in 2012 when Fleminger, Inc. filed a lawsuit against the FDA (Fleminger, Inc. v. U.S. Department of Health, and Human Services 2012). Fleminger asserted that the FDA had infringed upon the company’s First Amendment rights with a revised QHC (FDA_11). The claim, authored by the FDA, presented the green tea and cancer relationship while simultaneously negating the claim in the disclaimer by stating, “FDA does not agree that green tea may reduce that risk because there is very little scientific evidence for the claim.”

The FDA filed counter-complaints about the two QHCs that Fleminger had written and unlawfully posted to its website (Flem_08; Flem_10). The claims identified the evidence as “credible,” which mischaracterized the level of scientific certainty for the green tea-cancer relationship as asserted by the FDA. The agency also argued that by invoking the name of the FDA in Fleminger’s 2010 claim, consumers would be misled into believing that the FDA had endorsed the claim, which it had not (Fleminger, Inc. v. U.S. Department of Health, and Human Services 2012).

In its 2012 decision, the Court agreed with Fleminger and required the FDA to discontinue enforcement of its 2011 QHC (FDA_11) because the disclaimer negated the claim of a green tea-cancer relationship. However, the Court also required that Fleminger remove the two QHCs it had written from the company website (Flem_08; Flem_10) and refrain from writing QHCs in the future. Finally, the Court also suggested an alternative QHC (Court_12) which is one of the two green tea QHCs that the FDA now permits companies to use on relevant product labels (U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2011d).

As already stated, the assertions made by the FDA, Fleminger, and the Federal Court about public understanding of the various green tea QHCs have not been tested with consumers. To remedy this, we examine the following:

-

RQ1. What is the meta-message that consumers derive from the QHCs?

-

RQ2. Do consumers understand the FDA’s 2011 QHC as negating the claimed relationship between drinking green tea (yukichi fruit juice) and cancer (gastrocoridalis) risk reduction?

-

RQ3. What is the effect of the FDA summary statement on consumer perceptions of the QHC?

-

RQ4. Do consumers perceive a significantly greater quantity of scientific evidence for the claimed relationship when the QHC was written by Fleminger than when written by the FDA?

-

RQ5. Does familiarity/unfamiliarity with the diet-disease relationship affect consumer perceptions of the QHC?

Methods

Sample

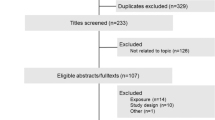

A nationally representative sample of English-speaking adults aged 55 years and older was recruited to participate in the study in January 2014. The panel of participants is maintained by GfK Custom Research, LLC (GfK) who enlisted the representative U.S. sample using probability-based recruitment.

Older adults were selected for this study since they comprise a large portion of the U.S. population in size and purchasing power (Nielsen and BoomAgers 2012, pp. 1-16; Colby and Ortman 2015, pp. 1-13). This segment of the U.S. population is also affected by cancer and other chronic diseases described in QHCs (American Cancer Society 2015; King et al. 2013, pp. 385-386). Older adults also read food labels (Govindasamy and Italia 1999, pp. 1-20; Jackey et al. 2017) and are influenced by health claims when making purchase decisions (Lalor et al. 2011, pp. 56-59).

Procedure

An online survey was administered by GfK in January 2014. Several rounds of cognitive testing and pretesting were used to improve question clarity and to reduce participant burden. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Informed consent was obtained on the initial screen, prior to the survey. To focus participant attention on the text of the QHCs, no label images or other graphics were included.

A 2 × 7 between-subjects study design was used. Participants were randomized to view one of the seven QHCs (Table 1) to test the effects of the disclaimer language in each. Participants were then randomly assigned to one of the two conditions reflecting claims about (1) the relationship between drinking green tea and reductions in the risk of breast cancer and/or prostate cancer, or (2) drinking yukichi fruit juice and reductions in the risk of gastrocoridalis, a fictitious but comparable diet-disease relationship. Yukichi fruit juice was described as a typical drink sold in stores and gastrocoridalis was introduced as a potentially painful and fatal disease. In the yukichi fruit juice condition, yukichi fruit juice substituted for green tea as the dietary component and gastrocoridalis replaced breast cancer and/or prostate cancer as the disease component in each of the seven QHCs tested.

Measures

A key construct measured was the meta-message or “implicit message” derived by consumers by reading the QHC. Participants were asked whether the statement (1) suggests that green tea is effective in reducing the risk of breast cancer and/or prostate cancer or gastrocoridalis; (2) suggests that green tea is not effective in reducing the risk of breast cancer and/or prostate cancer or gastrocoridalis; or (3) makes no suggestion about the effect of green tea in reducing the risk of breast cancer and/or prostate cancer or gastrocoridalis.

To assess the reason the participants thought the QHC was placed on the product label, the participants were also asked whether they thought the QHC was (1) voluntarily added by the company; (2) required by the government; or (3) put there for some other reason.

To measure perceived level of evidence behind each claim, the participants were asked, “Based on this statement, how much evidence is there that drinking green tea [or yukichi fruit juice] reduces the risk of breast cancer and/or prostate cancer [or gastrocoridalis]?” A 13-point response scale was used, anchored by 0 (no evidence) and 12 (complete evidence). The midpoint (6) was anchored by “some evidence.” For analysis, the scale was collapsed into four grades where zero meant “no evidence,” 1-3 represented a D-grade, 4-6 equalled a C-grade, 7-9, a B-grade, and 10-12 an A-grade.

To measure consumer perceptions of the quantity of evidence behind each claim, the participants were asked the open-ended question, “What number of studies do you think were conducted that support this statement?” They were also asked, “What number of studies do you think were conducted that did not support this statement?” For analysis, these responses were summed to yield the total number of studies for a diet-disease relationship.

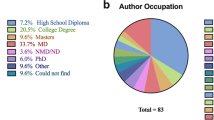

Demographic variables were extracted from the GfK panellist database. These included self-identified gender, race/ethnicity, age, marital status, education, employment, and income. Home ownership was used as a measure of socioeconomic status (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2005).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the study sample. Chi-squared tests of association were used to test associations of groups with categorical variables and Cramer’s V is reported to indicate the strength of these associations. The distribution of the estimated number of total studies evaluated by the FDA for the claimed relationship had positive skew and kurtosis. To account for this, the distribution was reciprocally transformed with a constant of one. Spearman correlation coefficient tests identify associations between ranked variables. Univariate analysis of variance with bootstrapping was used to test differences between groups in responses to ordinal/ratio measures. Welch’s F-test results are presented for univariate tests that violated the assumption of homogeneity of variances. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

The survey was completed by a nationally representative sample of 1,335 older adults, with a 60% completion rate (of 2,219). Most participants were 55-74 years old (n = 1,123, 89.1%), White (n = 1,060, 79.4%), with a high school degree or greater (n = 1,233, 92.4%), and reported a household income of less than $100 000 (n = 1,028, 77.0%). More than half of the participants reported that they had consumed green tea in the 12 months prior to the survey (n = 691, 51.8%). No significant differences were found between conditions or groups by sample characteristics, incidence of breast and prostate cancers (or of gastrocoridalis), or having consumed green tea in the past year, indicating successful randomization of the participants within the experimental design (Table 2).

RQ1: What Is the Meta-Message That Consumers Derive from the QHCs?

The results of a Chi-squared test showed a significant association between the QHC viewed and the reported meta-message, χ2(12, n = 1,312) = 395.535, p < .0001; V = 0.388, p < .0001. Consistent with Fleminger’s presumed goal of presenting the summary of the scientific evidence in the most favourable way, nearly three-quarters (n = 394, 73.4%) of the participants who viewed an unenforced claim written by Fleminger thought it suggested that green tea (yukichi fruit juice) was effective at reducing the risk of cancer (gastrocoridalis). In contrast, less than a third (n = 213, 27.5%) of those who viewed an enforced claim written by the FDA or the Court viewed it similarly χ2 (2, n = 1,312) = 303.246, p < .0001; V = 0.481, p < .0001 (Fig. 1).

In addition, 70% of the participants who viewed a claim authored by Fleminger (n = 329 of 540) thought the QHC was a voluntary addition to a product label. In contrast, 60% (n = 490) of those exposed to a QHC authored by the FDA or the Court reported that it was required to be on the label by the government, χ2(12, n = 1,322) = 289.006, p < .0001; V = 0.468, p < .0001 (Fig. 2). Thus, the claims seen as most suggestive that green tea (yukichi fruit juice) was effective at reducing the risk of cancer (gastrocoridalis) were also seen as most likely to have been placed on the label voluntarily. In contrast, those most likely to be seen as less likely to suggest that that green tea (yukichi fruit juice) was effective at reducing the risk of cancer (gastrocoridalis) were also seen as most likely to have been required to be on the label by the government.

RQ2: Do Consumers Understand the FDA’s 2011 QHC as Negating the Claimed Relationship Between Drinking Green Tea (Yukichi Fruit Juice) and Cancer (Gastrocoridalis) Risk Reduction?

The primary grievance contained in the federal lawsuit filed by Fleminger against the FDA was that the 2011 QHC written by the agency contained a disclaimer that began, “The FDA does not agree that…”. Fleminger argued the phrase negated the claim that green tea may reduce the risk of cancer, and the Federal Court agreed (Fleminger, Inc. v. U.S. Department of Health, and Human Services 2012).

As described above, all of the claims written by Fleminger and none of the claims written by the FDA or by the Court were interpreted by the majority of participants as endorsing the effectiveness of drinking green tea (yukichi fruit juice) to reduce the risk of cancer (gastrocoridalis). However, 44% of the participants who viewed the 2011 claim thought the meta-message was that green tea (yukichi fruit juice) was effective at reducing the risk of cancer (gastrocoridalis). This is a greater percentage than of those who viewed any of the other claims authored by either the FDA (2005B - 19%; 2005P – 13%) or the Court (34%) (Fig. 1).

RQ3: What Is the Effect of the FDA Summary Statement on Consumer Perceptions of the Claim?

Responses were grouped based on whether the QHC included an FDA summary statement (e.g., “FDA concludes”) (n = 974) or not (n = 361). Participants who viewed claims with an FDA summary statement perceived significantly greater evidence for the claimed relationship (M = 3.90, SD = 2.69 vs. M = 2.70, SD = 2.23) than others, Welch's F(1, 548.695) = 56.341, p < .0001. We then compared group responses to two nearly identical claims that were unlawfully written and used by Fleminger (Flem_10; Flem_08). The FDA summary statement in the Flem_10 claim reads, “The FDA has concluded there is credible evidence supporting this claim although the evidence is limited” while the Flem_08 claim reads, “there is credible evidence supporting this claim although the evidence is limited” (Table 1). This gave a sample of 173 who were assigned to view the Flem_08 claim and 183 that were assigned to the Flem_10 claim. The results show no significant differences in whether the claim was perceived as voluntary, required, or placed on a label for another reason, χ2(2, n = 356) = .416, p = .812 (Fig. 2).

When respondents considered whether the claim was perceived as voluntary, required, or placed on a label for another reason, a statistically significant association was also found between groups that viewed a claim with an FDA summary statement (n = 974) or not (n = 361), χ2(2, n = 1,322) = 131.568, p < .0001, V = 0.315, p < .0001. Nearly two-thirds of participants exposed to a QHC without an FDA summary statement reported the claim was a voluntary addition to product labels (59%, n = 212 (of 361)) while most who viewed a claim with an FDA summary statement believed it was required by the government (54%, n = 522 [of 974]) (Fig. 2).

RQ4: Do Consumers Perceive a Significantly Greater Amount of Scientific Evidence for the Claimed Relationship When the QHC Was Written by Fleminger than When Written by the FDA?

We further examined whether the claims written by Fleminger (that were rejected by the FDA and never enforced due to a mischaracterization of the scientific certainty) were seen as having been based on a greater number of studies than those written by the FDA or the Court. Group 1 comprised responses to the unenforced claims written by Fleminger that mischaracterized the scientific certainty (Flem_04 + Flem_08 + Flem_10 n = 546) and group 2 included responses to the QHCs enforced by the FDA that accurately characterize the scientific certainty (FDA_05b + FDA_05p + FDA_11 + Court_12 n = 789).

On the 13-point rating scale of how much evidence there is for the diet-disease relationship in the QHC, the mean score for the unenforced group of QHCs was four, which corresponds to a “C-grade” level of evidence. In contrast, the average group score for the enforced QHCs was two, Welch's F(1, 907.111) = 132.949, p < .0001. This score corresponds to a “D-grade” level of evidence, which is consistent with the level of evidence assigned by the FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2009).

A small, but statistically significant positive correlation was found between the estimated total number of studies evaluated for the claimed relationship and the rating of evidence, rs(1288) = .279, p < .0001. However, no significant difference was found between the groups of enforced and unenforced QHCs and the estimated total number of studies evaluated for the claimed relationships, F(1, 1296) = 2.604, p = .107.

It should be noted that the two QHCs written by the FDA and enforced in 2005 clearly state the number of studies evaluated for the claimed relationship. The claim about prostate cancer indicates two studies (FDA_05p) and the claim about breast cancer indicates three (FDA_05b). Participants who viewed the claim about breast cancer (2005_B) assigned the correct number of studies evaluated for the relationship between green tea (yukichi fruit juice) and cancer (gastrocoridalis). Participants in the green tea condition viewed the claim about prostate cancer estimated four studies, whereas those in the yukichi fruit juice condition estimated two though when looking at all responses, the median is three (Fig. 3).

RQ5: Does Familiarity/Unfamiliarity with the Diet-Disease Relationship Affect Consumer Perceptions of the QHC?

Prior familiarity with diet-disease relationships has been shown to influence perceptions of health claims through confirmatory bias (Walker Naylor et al. 2009, pp. 221-233). Therefore, we compared responses between the green tea-cancer (n = 666) and yukichi fruit juice-gastrocoridalis (n = 669) conditions. The results suggest that existing familiarity with the green-tea/cancer diet-disease relationship had an effect on participant responses across each of the measures.

Overall, the greatest proportion of respondents thought the QHC suggested that green tea (yukichi fruit juice) was effective at reducing the risk of cancer (gastrocoridalis), (n = 339, 51.4% and n = 268, 41.0%, respectively). However, a significant association was found between the conditions of green tea-cancer and yukichi fruit juice-gastrocoridalis for the meta-message, χ2(2, n = 1,312) = 23.807, p < .0001, V = .135, p = .0001. In comparison with the green tea condition, a greater percentage of participants in the yukichi fruit juice condition thought the claim did not make any suggestion about its effect on reducing the risk of gastrocoridalis (n = 216, 33.1%) than green tea’s effect on cancer (n = 142, 21.5%).

A Chi-squared test also showed associations between conditions and whether the claim was required or voluntary, χ2(2, n = 1,322) = 15.827, p < .0001, V = .109, p < .0001. Just under half of the participants in the yukichi fruit juice condition reported that the QHC was required on labels by the government (n = 327, 49.5%) while a greater percentage in the green tea condition thought the QHC was voluntarily added by the company (n = 286, 43.3%).

On average, participants in the green tea condition reported greater perceived evidence for the claimed relationship (M = 3.39, SD = 2.58) than participants in the yukichi fruit juice (M = 2.65, SD = 2.19) condition. This difference, −.733, 95% CI [−.99313, −.46832], was significant Welch’s F(1, 1283.496) = 30.807, p < .0001. A one-way ANOVA test also determined that the estimated number of studies was significantly higher in the green tea condition than in the yukichi fruit juice condition Welch’s F(1, 1277.196) = 15.914, p < .0001.

There were also significant interactions between the conditions and groups, F(6, 1304) = 2.924, p = .008, partial η2 = .013. Participants who observed the claim written by Fleminger in 2010 (Flem_10) rated the evidence as significantly higher (1.437, 95% CI [0.78, 2.10]) for green tea, F(1, 1304) = 18.184, p < .0001, partial η2 = .014 than for yukichi fruit juice. The same was true for the current claim written by the Court and enforced by the FDA (Court_12) for green tea than yukichi fruit juice (+1.418, 95% [0.78, 2.06]), F(1, 1304) = 18.814, p < .0001, partial η2 = .014.

Discussion

The language in qualified health claims is important as demonstrated by the lawsuits about their description of evidence (Berhaupt-Glickstein et al. 2014, pp. 62-70). Stakeholders disagree about the way to characterize the supporting science for diet-disease relationships within QHCs. The food and dietary supplement industries value QHCs for their potential marketing power. The FDA is charged with preventing consumers from being misled; in this case, being misled from a mischaracterization of the strength of science for a claimed relationship. The Court has an interest both in the boundaries of commercial speech and in supporting the federal government in protecting the public’s health through the least restrictive means necessary. Unfortunately, these diverse goals are often in conflict. The evolving green tea QHC serves as a case study for issues surrounding these claims.

This study addresses specific issues raised as part of the conflict over how to best describe the scientific evidence for a relationship between drinking green tea and reductions in breast and prostate cancer. It shows that the language in the QHC disclaimers written by Fleminger, Inc. did suggest to consumers that green tea (yukichi fruit juice) was effective in reducing the risk of cancer (gastrocoridalis). They also elicited a sense that there is greater scientific evidence behind this diet-disease relationship than is warranted by a D-level claim. These results support the FDA’s contention that Fleminger’s QHCs mischaracterized the level of scientific certainty for the green tea-cancer relationship.

The point of contention that led to the federal lawsuit filed by Fleminger was the claim written by the FDA in 2011. The Court found that this claim and specifically the phrase, “FDA does not agree…” (FDA_11) negated the green tea-cancer relationship. However, of the participants who saw FDA’s 2011 QHC, the largest proportion (44%) reported that the claim suggested that green tea (yukichi fruit juice) was effective at reducing the risk of cancer (gastrocoridalis). Moreover, the proportion who thought that the 2011 QHC communicated that drinking the product was effective in reducing the risk of disease was greater than of those who viewed any of the other claims authored by either the FDA or the Court. Thus, while the 2011 QHC was not seen by the majority of participants as endorsing the diet-disease relationship, its disclaimer, which contained the phrase “The FDA does not agree,” was apparently interpreted as less negative than disclaimers without the phrase. In addition, FDA’s 2011 QHC was less likely to be seen by participants as having been required to be on the label than the Court’s 2012 version, which was intended to remediate the perceived “negation” of the diet-disease relationship and is currently enforced by the FDA.

The FDA objected to what appeared to be Fleminger’s appropriation of its imprimatur by claiming in its 2010 QHC (Flem_2010) that “The FDA has concluded that there is credible evidence supporting this claim...”. Our data indicate that FDA’s objection may have been well founded. Overall, participants who viewed claims with an FDA summary statement perceived significantly greater evidence for the claimed relationship than claims which did not have such a statement. However, when we compared responses to two Fleminger claims that are nearly the same, one references the FDA (Flem_10), while the other does not (Flem_08); we found no significant differences in how the claim was perceived. A third of participants though it was voluntary, a third thought it was required by government, and a third thought it was there for another reason. This finding may have important implications. Since the resolution of the Fleminger lawsuit, all enforced QHCs now contain an FDA summary statement.

Finally, our results show that the same disclaimer language is perceived differently when applied to familiar versus unfamiliar diet-disease relationships. In comparison to those who saw a QHC about yukichi fruit juice and gastrocoridalis, participants who saw claims about green tea and cancer perceived a greater level evidence for the claimed relationship and they estimated that a greater number of studies supported the relationship. Not surprisingly, a greater percentage of those who saw a green tea claim also thought that it implied that it was effective at reducing the risk of cancer. Thus, claims applied to familiar diet-disease relationships may be subject to confirmation bias, while those introducing new or unfamiliar diet-disease relationships using the same disclaimer language may be viewed more sceptically.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study is the first to test the assertions and complaints made by stakeholders surrounding a lawsuit and the proceedings about consumer understanding of the scientific evidence described in QHCs. A strength of this study is that it tested and compared QHCs that were petitioned, previously permitted by the FDA, or unlawfully used by Fleminger. Further, this was a text-only study, so participants focused on the claims versus physical product attributes such as package aesthetics or other label information, which introduces additional potential biases. A limitation of the study is that it did not include a control group that did not view any QHC. However, inclusion of such a group was not possible, since those in the control could not have responded to questions about the meta-message of the claim, or why it would be on a label. Furthermore, the study aimed to evaluate the differences in consumer perceptions among actual QHCs proposed or used by stakeholders and to test the assertions made by the various stakeholders about those claims.

It is important to note that only D-grade QHCs were examined by this study. We suspect that consumers will have even greater difficulty accurately judging the level of evidence when confronted with QHCs of different grades of evidence (Derby and Levy 2005, pp. 1-41; U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2009). Examining these factors across grades could help to systematically identify how to reach the “fundamental goal [of claims]…to present uncertainty in a way that is not overly complicated, yet sufficiently detailed…” (Dieckmann et al. 2012, pp. 717-735). Therefore, future research should look at these and other factors in enforced QHCs, that are scientifically accurate, across grades of evidence, including A-grade health claims.

Conclusion

In focusing on the various assertions made by stakeholders in the Fleminger, Inc. v. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2012) court case, our empirical findings demonstrate that the disclaimer, which describes the totality of scientific evidence for a diet-disease relationship, does affect consumer perceptions of the meta-message, the purpose of the claim, and the amount of evidence for the D-grade claims about green tea and cancer. This supports the argument that specific disclaimer language can significantly alter perceptions of a product and its impact on health. These altered perceptions further affect both the intent to purchase (Berhaupt-Glickstein et al. 2019, pp. 1-18) and the actual purchase of products bearing health claims (Wills et al. 2012, pp. 229-236).

The Fleminger court case echoes the challenges surrounding the entire QHC system. To satisfy stakeholders, an ideal QHC would inform decision-making about the added health value of a product (Lahteenmaki 2012, pp. 196-201) with an accurate description of evidence that is linear with scientific certainty (U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2009) and does not undermine the claimed relationship (i.e., contradict or overly technical) (Alliance for Natural Health U.S. v. Sebelius 2011).

Our study shows that it is possible to use well-designed consumer research to evaluate whether specific QHC disclaimer language effectively communicates the level of scientific evidence behind diet-disease relationships. Such research should be conducted prior to enforcing any future QHCs.

Notes

Petitions require a definition of the dietary substance(s), diseases/health conditions, copies of a literature search and summary of the scientific data about the diet-disease relationship, information about adverse effects, and proposed health claims (Kavanaugh et al. 2007).

For this paper, we refer to these evidence grades as an organizing principle, with the understanding that they are no longer in use.

References

American Cancer Society. (2015). Cancer facts and figures 2015. Retrieved from http://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2015/cancer-facts-and-figures-2015.pdf. Accessed 1 Jul 2015.

Berhaupt-Glickstein, A., Nucci, M. L., Hooker, N. H., & Hallman, W. K. (2014). The evolution of language complexity in qualified health claims. Food Policy, 47, 62–70.

Berhaupt-Glickstein, A., & Hallman, W. K. (2017). Communicating scientific evidence in qualified health claims. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 57(13), 2811–2824.

Berhaupt-Glickstein, A., Hooker, N. H., & Hallman, W. K. (2019). Qualified health claim language affects purchase intentions for green tea products in the United States. Nutrients, 11(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11040921.

Colby, S. L., & Ortman, J. M. (2015). Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population: 2014 to 2060. Current population reports (No. P25-1143). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Derby, B. M., & Levy, A. (2005). Effects of strength of science disclaimers on the communication impacts of health claims (Working Paper No.1, September 2005). U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Dieckmann, N. F., Peters, E., Gregory, R., & Tusler, M. (2012). Making sense of uncertainty: Advantages and disadvantages of providing an evaluative structure. Journal of Risk Research, 15(7), 717–735.

Emord, J. W., & Schwitters, B. (2012). Do qualified health claims deceive when they are not misleading? Perspectives from the European Union and United States. Food and Drug Policy Forum, 2(12), 1–12.

Fitzgerald Bone, P., Kees, J., France, K. R., & Kozup, J. (2012). Consumer confusion: A lose/lose situation. Marketing and Public Policy Conference Proceedings, 22, 131-132.

Government Accountability Office. (2011). Food labeling: FDA needs to reassess its approach to protecting consumers from false or misleading claims. (No. GAO-11-102). Retrieved from http://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-11-102.pdf. Accessed 10 Sept 2014.

Govindasamy, R., & Italia, J. (1999). Evaluating consumer usage of nutritional labeling: The influence of socio-economic characteristics. (No. P-02137-1-99). Retrieved from http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/36734/files/pa990199.pdf. Accessed 13 Apr 2012.

Hasler, C. M. (2008). Health claims in the United States: An aid to the public or a source of confusion? The Journal of Nutrition, 138(6), 1216S–1220S.

Hooker, N. H., & Teratanavat, R. (2008). Dissecting qualified health claims: Evidence from experimental studies. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 48(2), 160–176.

Ippolito, P. M., & Mathios, A. D. (1993). New food labeling regulations and the flow of nutrition information to consumers. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 12(2), 188–205.

Jackey, B. A., Cotugna, N., & Orsega-Smith, E. (2017). Food label knowledge, usage and attitudes of older adults. Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics, 36(1), 31-47.

Kavanaugh, C. J., Trumbo, P. R., & Ellwood, K. C. (2007). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration's evidence-based review for qualified health claims: Zomatoes, lycopene, and cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 99(14), 1074-1085

Kim, J. Y., Kang, E. J., Kwon, O., & Kim, G. H. (2010). Korean consumers’ perceptions of health/functional food claims according to the strength of scientific evidence. Nutrition Research and Practice, 4(5), 428–432.

King, D. E., Matheson, E., Chirina, S., Shankar, A., & Broman-Fulks, J. (2013). The status of baby boomers’ health in the United States: The healthiest generation? Research letter. JAMA Internal Medicine, 173(5), 385–386.

Lahteenmaki, L. (2012). Claiming health in food products. Food Quality and Preference, 27(2), 196–201.

Lalor, F., Madden, C., McKenzie, K., & Wall, P. G. (2011). Health claims on foodstuff: A focus group study of consumer attitudes. Journal of Functional Foods, 3(1), 56–59.

Nielsen and BoomAgers. (2012). Introducing Boomers: Marketing’s most valuable generation. Retrieved from https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/report/2012/introducing-boomers-marketing-s-most-valuable-generation/. Accessed 31 Mar 2017.

Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. (2015). Frequently asked questions: Regulations and the rulemaking process. Retrieved from http://www.reginfo.gov/public/jsp/Utilities/faq.jsp. Accessed 2 Mar 2016.

Reinhardt-Kapsak, W., Schmidt, D., Childs, N. M., Meunier, J., & White, C. (2008). Consumer perceptions of graded, graphic and text label presentations for qualified health claims. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 48(3), 248–256.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Office of Policy Development and Research. (2005). Homeownership gaps among low-income and minority borrowers and neighborhoods. Retrieved from http://www.huduser.gov/Publications/pdf/HomeownershipGapsAmongLow-IncomeAndMinority.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2016.

U.S. Federal Trade Commission. (2006). In the matter of assessing consumer perceptions of health claims. (Public Meeting; Request for Comments No. Docket No. 2005N-0413). Retrieved from http://www.ftc.gov/policy/advocacy/advocacy-filings/2006/01/ftc-staff-comment-food-drug-administration-matterassessing. Accessed 13 Nov 2014.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2003). Guidance for industry: Interim procedures for qualified health claims in the labeling of conventional human food and human dietary supplements. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/guidance-industry-interim-procedures-qualified-health-claims-labeling-conventional-human-food-and. Accessed 15 Feb 2012.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2009). Experimental study of qualified health claims: Consumer inferences about monounsaturated fatty acids from olive oil, EPA and DHA omega-3 fatty acids, and green tea. OMB no. 0910-0952. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/experimental-study-qualified-health-claims-consumer-inferences-about-monounsaturated-fatty-acids-4. Accessed 27 Apr 2017.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2011a). Consumer health information for better nutrition initiative: Task force final report. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/consumer-health-information-better-nutrition-initiative-task-force-final-report. Accessed 9 Jun 2013.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2011b). Experimental study of health claims on food packages: Preliminary topline frequency report (May 2007).

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2011c). Guidance for industry: Evidence-based review system for the scientific evaluation of health claims - final. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/guidance-industry-evidence-based-review-system-scientific-evaluation-health-claims. Accessed 14 Sept 2012.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2011d). Qualified health claims: Letters of enforcement discretion. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/Food/LabelingNutrition/LabelClaims/QualifiedHealthClaims/ucm073992.htm#nuts. Accessed 14 Sept 2012.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2013). Guidance for industry: A food labeling guide (Appendix C: Health claims). Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/guidance-industry-food-labeling-guide. Accessed 7 Jul 2014.

Walker Naylor, R., Droms, C. M., & Haws, K. L. (2009). Eating with a purpose: Consumer response to functional food health claims in conflicting versus complementary information environments. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 28(2), 221–233.

Wills, J. M., Storcksdieck genannt Bonsmann, S., Kolka, M., & Grunert, K. G. (2012). Symposium 2: Nutrition and health claims: Help or hindrance European consumers and health claims: Attitudes, understanding and purchasing behaviour. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 71, 22-236.

Wong, A. Y.-T., Lai, J. M. C., & Chan, A. W.-K. (2015). Regulations and protection for functional food products in the United States. Journal of Functional Foods, 17, 540–551.

Cases

Fleminger, Inc. v. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [2012], 854 F. Supp. 2d 192 (D. Conn.)

Alliance for Natural Health US v. Sebelius [2010] 714 F. Supp. 2d 48 (D.D.C.)

Alliance for Natural Health US v. Sebelius [2011] 786 F. Supp. 2d 1 (D.D.C.)

Pearson v. Shalala [1999] 164 F.3d 650 (D.C.C.)

Legislation

United States

Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act 1938 – Title 21. U.S.C. § 343(r)(3)(B)(i)

Nutrition Labeling and Education Act 1990

Funding

This work was supported by Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Investigator Awards in Health Policy Research, Award Number 66487; and Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey Robert T. Rosen Graduate Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Berhaupt-Glickstein, A., Hallman, W.K. An Investigation of the Contested Qualified Health Claims for Green Tea and Cancer. J Consum Policy 44, 259–277 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-021-09481-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-021-09481-5