Abstract

The rapidly advancing digitalisation of the global economy, particularly the emergence of quasi-monopolists with the ability to define the rules of the game, poses numerous challenges to competition law as it is now practised worldwide. The European Union and China, in particular, have recently taken up these challenges with far-reaching reforms of their respective competition law regimes. This paper analyses these reforms and trends from a critical perspective informed by ordoliberalism, one of the arguably most influential schools of competition thought. First, the core ideas of the early Freiburg School on competition are distilled. The subsequent sections compare this ideal type with current developments in EU and Chinese competition law. The discussion of similarities and differences shows that both reform agendas suffer from similar problems connected to the rule of law and suggests that a modernised ordoliberal competition law approach must be guided not only by substantive but also by procedural aspects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction: ordoliberalism goes China?

The rapidly advancing digitalisation of the global economy, particularly the emergence of quasi-monopolists with the ability to define the rules of the game, poses numerous challenges to competition law as it is now practised worldwide. While consumers certainly benefit from the often free and superior services and products offered online, it becomes increasingly clear that the digital economy is changing the nature of market competition itself: data-driven algorithms that can adjust prices in real-time enable ‘tacit’ cooperation between competitors, behavioural discrimination allows firms to track consumers and charge them with their maximum ‘reservation’ price, and ‘gatekeeper’ platforms have the power to determine the flow of personal data (Ezrachi & Stucke, 2016). As Big Tech firms hold a large part of the world’s data, the ability of data-driven small businesses to emerge and innovate is severely hampered (Lee, 2018). US antitrust activist Barry Lynn argues that the power of Google (Alphabet), Apple, Facebook (Meta), Amazon, and Microsoft (in short: GAFAM) to manipulate the flows of information and commerce even threatens liberty and democracy as such (Lynn, 2020). A growing group of scholars describes the potential of this small number of private companies to guide global collective behaviour, with significant repercussions beyond the economic realm (Bak-Coleman, et al., 2021).

This development is particularly problematic from the perspective of ordoliberalism, one of the arguably most influential schools of competition thought, whose legal impact extends beyond its domestic German borders (Gerber, 1998). Above all, the first generation of the ordoliberal school, which is usually traced back to the 1936 manifesto jointly published by the economist Walter Eucken and the two lawyers Franz Böhm and Hans Großmann-Doerth, had vehemently argued against any concentrations of economic power, which threatened to violate the freedom of other market actors (Böhm, et al., 2017). Therefore, they would have been alarmed by the persistent market shares and the unparalleled possession of data by GAFAM. Moreover, as ordoliberals were aware of the nexus between competition and democracy due to their experiences in interwar Germany (Deutscher & Makris, 2016; Wegner, 2019), they would agree that competition authorities need to counteract the growing monopolisation of communication and media channels to protect the basis of democratic societies (Banasiński & Rojszczak, 2022). Finally, for today’s digital giants, privately arranged rules have become a tool for producing information domination, distributing social costs in ways that benefit themselves, and controlling and coordinating market players in platform markets (Viljoen, et al., 2021). Großmann-Doerth had described early on the threats stemming from such a ‘self-created law of the economy’ (Großmann-Doerth, 2008). Rather than allowing for such a laissez-faire situation, ordoliberalism would require policymakers to choose a societally beneficial outcome, such as a more decentralised market structure with standardised rules of the game, and then arrange the legal framework to achieve it.

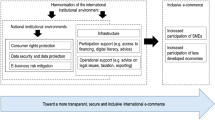

At first sight, this thinking seems to align well with the current efforts of the European Union (EU) and the Chinese government, which both have taken up the challenges of the digital economy with far-reaching reforms of their respective competition law regimes. At the end of 2020, the European Commission proposed two significant pieces of legislation, the Digital Services Act (DSA) and the Digital Markets Act (DMA). The DSA would require large platforms to show regulators how their algorithms work and target advertisements to their users, while the DMA aims to stop their anti-competitive practices. Realising that digitalisation will profoundly transform the ‘socialist market economy with Chinese characteristics’ (Hong, 2020), the Chinese leadership likewise enacted a ‘tech crackdown’ in 2021 directed at its most potent domestic tech companies, including the internet conglomerates Tencent and Alibaba. Big Tech companies have, by now, also been targeted in several competition law cases, which addressed both their market behaviour and their acquisition of nascent competitive threats.Footnote 1 However, as competition lawyers and officials increasingly realise that the usual case law procedure is too slow to grapple with fast-moving digital markets (Küsters, 2022a, pp. 109–111), the main emphasis continues to be on regulatory reforms.

As the presence of today’s digital giants poses precisely the type of dangers feared by early ordoliberals, it is timely to evaluate the latest competition law reforms for the digital age from an ordoliberal perspective. Previous work suggests that ordoliberal theory could contribute to this reform process through a renewed focus on structural remedies, per se rules, and a historical interpretation of EU competition law (Küsters & Oakes, 2022). This sentiment seems to be shared by some policymakers. In spring 2022, for instance, the German Economic Ministry’s new competition policy agenda announced that today’s digital challenges necessitate a renaissance of ordoliberalism (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz, 2022). The responsible Secretary of State, Sven Giegold, clarified that he drew inspiration from Freiburg School thinking (Giegold, 2022). However, while several legal-historical studies suggest an ordoliberal influence on the drafting of the European competition rules (Gerber, 1998; Wegmann, 2002, 2008), this does not guarantee that legal scholars will be convinced that ordoliberal theory matters for the current enforcement of these rules (Colomo, 2013, p. 423). By outlining in detail how a ‘contemporary ordoliberalism’ (Dold & Krieger, 2019, p. 243) would assess the current regulatory approaches to the digital economy, it becomes possible to counter the view that the ordoliberal perspective is no longer of any analytical value (Makris, 2021, p. 22).

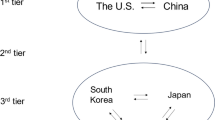

From the perspective of constitutional political economy, China can serve as a valuable point of comparison with the ordoliberal and the European views on competition policy. For some years now, the unparalleled collection of real-time data has allowed the Chinese government to maintain political control, while enabling a growing private sector to train algorithms on incredibly detailed datasets to offer innovative consumer products and services (Li, 2018). The ‘techlash’ of 2021 can be understood as a reaction from the Chinese leadership, which realised that the domestic digital giants could build a power base equal to the political leadership. The uncertainty about the Chinese state’s underlying motives has led to significant market effects. As both Western and Chinese state authorities are struggling with protecting their arguably very different political systems from the digital revolution, ‘a comparative analysis may reveal a parallel between democratic states and their relationship with competition law, and other types of states and their relationship with competition law’ (Robertson, 2022, p. 7).

In addition, a comparison with current Chinese developments in competition policy is also illuminating from a perspective focused on the history of economic thought. Since the late nineteenth century, translated Western works on liberalism became increasingly available in China (Feng, et al., 2017). Starting with the first long decade of reform and opening up (1978–92), the Chinese state exhibited a growing interest in transplanting neoliberal ideas into its particular economic model (Weber, 2022). A key figure in this respect is Friedrich Hayek, one of the ‘ancestral wise men’ resuscitated to inform Chinese thinking about ‘the economic’ (Karl, 2017, p. 75). The most prominent example is Zhang Weiying, a Professor of Economics at Peking University with strong Austrian leanings. Less known is that the Chinese state has also sought guidance from ordoliberal sources. Modern ordoliberals have been asked to translate texts of the early Freiburg School into Chinese to help implement some aspects of the Social Market Economy (Feld, et al., 2019), with the Walter Eucken Institute commenting on Twitter ‘Ordoliberalism goes China.’Footnote 2 Already since the early 2000s, the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung has organised Chinese workshops and publications on ordoliberal competition law (Hax, 2007 (in Chinese)), leading up to the 2008 implementation of the Chinese competition law that closely resembles that of the EU (Zhang, 2021, p. 2). Between 1993 and 2019, the Unirule Institute of Economics, a Beijing-based Chinese think tank dedicated to ‘universal rules,’ promoted a specific type of institutional economics echoing Eucken’s thinking in orders and established connections with the neoliberal Mont Pèlerin Society. The former deputy director of Unirule, Professor Feng Xingyuan, is an economist who has studied ordoliberalism and published books on Hayek and the Austrian School. Another member of Unirule, Jack Ma Junjie, travelled to Germany to visit the Walter Eucken Institute.

Did ordoliberal competition thought indeed ‘go to China’? More generally: to which extent are ordoliberal ideas reflected in competition law reforms currently planned or implemented in Europe and China, and what can be learned from these similarities and differences for a modern ordoliberal approach to competition policy? To answer these questions, the paper proceeds in three steps. First, the competition conception of the early Freiburg School must be identified (1). The subsequent sections compare this ideal type with current developments in EU (2) and Chinese (3) competition law. This exercise is not intended to be an exhaustive examination of proposed changes to competition laws; instead, it aims to assess the extent to which these changes serve ordoliberal objectives. The discussion of similarities and differences shows that modern ordoliberal competition law thinking must be guided not only by substantive but also by procedural aspects.

2 Competition policy from an ordoliberal perspective

For Eucken, competition was the central pillar of the ‘economic constitution’ that he and his followers hoped to implement in the post-war world (Eucken, 2017). This ‘neoliberal thought collective’ (Mirowski & Plehwe, 2009) can be understood as a transnational network of scholars working in Freiburg, Chicago, Geneva, and other places as a reaction to the crisis that classic liberalism experienced in the turbulent interwar period, marked by the Great Depression, political instability, and disintegration of global markets (Köhler & Kolev, 2011). However, there are essential differences in how sub-strands of this neoliberal network thought about competition (Young, 2017). In particular, ordoliberalism was more than an economic programme focused on unleashing free markets; it was, above all, a broader cultural programme with religious, social, and philosophic underpinnings (Dyson, 2021; Hien & Joerges, 2017; Slobodian, 2018). In light of these varieties of neoliberalism, the following survey focuses on a group of scholars usually associated with the broader Freiburg School of Law and Economics.

Even within this group, there were certain conceptual differences regarding, for instance, the extent of state intervention in the economy. In addition, there were incremental conceptual and semantic changes over time, as a quantitative analysis of the ORDO Yearbook between 1948 and 2014 shows (Küsters, 2023). Accordingly, the key characteristics distilled in the following should be treated as a rough ideal type chosen to illuminate the subsequent comparison between current EU and Chinese reforms and mainly refer to the school’s first generation. While the author is aware of the epistemological problems associated with such an approach, building ideal types has become a robust analytical tool in social science research over the years, and is justified here in particular as the paper is less interested in a precise historical reconstruction of ordoliberalism than in deriving theoretical premises for a discussion of modern competition law. This is challenging because, in contrast to the well-known Chicago School and its ‘consumer welfare standard,’ the ordoliberals were much less mathematically oriented (Slobodian, 2018, p. 58), which makes it more difficult to relate them to current competition economics as described in textbooks on Industrial Organisation. In particular, the five elements of ordoliberal competition policy that are emphasised here relate to: structuralist thinking, ethical standards related to ‘competition on the merits,’ extra-economic effects of competition, activist policy stance, and the rule of law.

To begin with, early ordoliberals were united by their vision of an atomistic market structure, as suggested by their concept of ‘complete competition’ (vollständige Konkurrenz). For Eucken’s student Leonhard Miksch, complete competition had a ‘dual nature,’ as it referred both to open competition, in the sense of free access to markets, as well as to a specific market situation, which presupposed ‘a multitude of market participants with approximately equal supply or demand capacity on both the supply and the demand side’ (Miksch, 1937, pp. 28–29). In other words, he described a level playing field characterised by numerous independent market actors as a guideline for competition policy. Contrary to many misperceptions in the literature, the early ordoliberals did not claim that the model market form of ‘complete competition’ was always practically enforceable, nor did they fail to recognise the character of competition as a dynamic process (Willgerodt, 1975). For practical purposes, Miksch noted, the ‘economically relevant dividing line’ denoted the point ‘where market influence begins to determine the behaviour of the entrepreneur’ (Miksch, 1937, p. 30, fn. 25). This structuralist thinking proved to be highly influential: In the case law of the CJEU, one repeatedly finds the view that competition law must protect not only the interests of consumers but also the market structure and competition itself.Footnote 3

Early ordoliberal competition thought also included a complementary, behavioural perspective based on the notion of ‘competition on the merits,’ or Leistungswettbewerb (Kolev, 2015, p. 428, 2017, p. 171 ff.; Vanberg, 1997, p. 718 ff.). In his seminal dissertation, Böhm defined ‘competition on the merits’ as an ‘orderly combat event’ in which all participants used their ‘socially beneficial’ skills to solve a specific economic ‘task’ and in which the ‘victory prize’ accrued to the person who had solved this task best (Böhm, 1933, p. 212). This notion included a normative element, driven by the ethical understanding of ‘performance’ (Leistung) that shaped the German bourgeoisie and the prevailing sports metaphoric at the time (Pyta, 2009; Verheyen, 2018). For early ordoliberals, the effectiveness of the ‘performance principle’ depended on ensuring that ‘competition cannot take place at the expense of upstream suppliers, creditors, shareholders, workers, or the tax coffers’ (Miksch, 1937, p. 41). They explicitly made clear that competition in the sense of Leistungswettbewerb was ‘not a fight man against man, but a race, i.e. the performance of the participants is not occurring in a clashing [aufeinanderprallender] direction, as in a duel, a wrestling match, a preliminary fight, or a war, but in a parallel direction’ (Böhm, 1937, p. 124). The emphasis was not on competition as a zero-sum game, but on following ethical behavioural standards of competition to achieve a societal optimum. The notion of ‘competition on the merits’ has also entered influential judgments in EU competition law (Schinkel & LaRocuhe, 2014).Footnote 4

Crucially, ordoliberal arguments about competition were situated ‘between norms and reason’ as they often mixed ideas from the natural law tradition, humanism, moral philosophy, classical liberalism, and Protestantism (Miettinen, 2021, p. 274). In particular, early ordoliberals argued that competition should be legally protected not only for its welfare-maximising qualities but also as a value in itself, as it limited the extent of economic power, created the preconditions for human freedom, and protected equality of opportunity (Deutscher & Makris, 2016). In a time when digital giants once again highlight that powerful economic players are impacting not only the functioning of markets but also democratic societies, this thinking merits re-consideration (Küsters & Oakes, 2022). Similarly, both the sociological ‘structural policy’ advocated by Wilhelm Röpke and the concept of a Vitalpolitik established by Walter Rüstow reflected these thinkers’ insight that an economic and legal programme focused on increased competition needed to be complemented with a comprehensive set of socio-cultural values, primarily related to small businesses, families, and local communities (Behlke, 1961, p. 71 ff.; Dyson, 2021, pp. 129–161; Ptak, 2009, p. 106 ff.). This intimate relationship between competition, political ideas, and social concerns in ordoliberal theory was conceptually based on the assumption of ‘interdependence’ between the economic, political, and social orders (Petersen, 2019, p. 226 f.). In practice, these normative considerations often led to a focus on protecting small- and medium-sized enterprises, or SMEs (Wigger & Nölke, 2007).

On this conceptual and normative basis, ordoliberals advocated, especially in their early writings, for an activist competition policy that aimed to correct for imbalances in the distribution of economic power not only ex-post, as, e.g., in an abuse control regime for dominant companies, but also ex-ante, primarily through rigorous de-cartelisation and de-centralisation of the economy (Böhm, 2017a). Their concern for a decentralised market structure meant that for some ordoliberals, competition law regimes should include an instrument of enterprise divestiture, which, however, should be used only to protect competition in general, not for purposes transcending competition like saving employment (Möschel, 1980). Where de-centralisation was impossible, Miksch concluded, an independent competition authority should enforce ‘as-if’ prices simulating the market price that would have resulted in the scenario of ‘complete competition’ (Miksch, 1937, p. 41). While it is important to note both that Böhm later became more pragmatic and accepted an abuse control for dominant companies (Küsters, 2022b, ch. II; Murach-Brand, 2004) and that not all ordoliberals shared this affinity for mandating competitive prices (Schweitzer, 2007, p. 15), these aspects of the early debate nevertheless illustrate the extent to which some founding ordoliberals were ready to infer in property rights and entrepreneurial freedom to protect their vision of a competition-centred economic constitution.

The final key characteristic of the ordoliberal competition tradition concerns its idea that the competencies of the government and public administration, including in the field of competition law, should be regulated according to the rule of law (Willgerodt, 1979). While the actual content of the rule of law is debated to this day, lawyers generally agree that it comprises formal principles, concerning the generality, clarity, publicity, and stability of the legal rules that govern a society, as well as procedural principles, characterising the institutional processes by which these rules are administered (Waldron, 2020). Without the ‘large, central figure of the monopoly office,’ Eucken wrote in his Grundsätze, ‘the order of competition and with it the modern constitutional state [Rechtsstaat] are threatened. The monopoly office is just as indispensable as the Supreme Court’(Eucken, 2004, p. 294). When the state takes action against cartels and monopolies, ordoliberals reasoned, it also protects freedom and private law. Böhm, therefore, elevated the task of the law to neutralise the element of power in human relations to the ‘general idea of the rule of law’ (Nörr, 1994, p. 157). A rule-based order was seen as a powerful tool for limiting the power of interest groups and the discretionary political decisions that characterised the Weimar and NS periods, in which the ordoliberals developed their ideas. Consequently, the competition authority must decide independently from government pressures (Möschel, 1997).

This procedural element of ordoliberal competition thought remained relevant in the post-war period. Eucken’s assistant Hans Otto Lenel used similar arguments as his teacher when he rejected the possibility of a ministerial permit for mergers restricting competition in the 1970s (Lenel, 1972, p. 326). The alleged ‘macroeconomic benefits’ of those mergers singled out for permission were too vague to operate a rule-based instead of a discretionary competition policy, Lenel argued, and there was a lack of legal control of the permits, since legal recourse was only provided for their rejection. In an influential ORDO article, Böhm summarised his thinking on the nexus between private autonomy, market order, and rule of law under the notion of the ‘private law society,’ or Privatrechtsgesellschaft (Böhm, 1966). For post-war ordoliberals, following the ‘rule of law’ criterium means that rules of conduct apply equally to all citizens and the state and that they are general and abstract (Möschel, 1979, p. 297). The character of ordoliberal competition thinking, therefore, reflects, as Kenneth Dyson has argued, a continental Roman-law context, as opposed to the common-law approach, since ‘[t]he Roman-law tradition emphasised the role of exhaustively codified rules in mitigating the uncertainty of law and giving predictability to individuals in managing their economic, social, and political lives’ (Dyson, 2021, p. ix). The rule of law requirement is an element not typically mentioned specifically with respect to ordoliberal competition thought but it is, as will be shown, a key criterion for defining an ordoliberal position towards current competition law developments in the EU and in China.

3 Making European competition policy fit for the digital age

Under the banner of a ‘competition policy for the digital age,’ the European Commission has been pushing ahead with a reform process since 2018, which has included revisions of the guidelines, the block exemption regulations, the notice on market definition, as well as detailed consultation processes and expert reports (Küsters, 2022a). This culminated on December 15, 2020, when the Commission released a Digital Markets Act (DMA) proposal, which was later further adapted as part of the usual European law-making process.Footnote 5 The plan imposes on so-called ‘gatekeepers,’ defined as large digital platforms that have become vital gateways for conducting business in the digital economy and for accessing digital products and services, a set of rules, such as the obligation to provide practical portability of data. The DMA amounts to the most significant overhaul of the digital regulatory landscape to date and thus forms the centrepiece of the following analysis.

To begin with, one can compare the ordoliberal understanding of competition, as contained in the notions of ‘complete competition’ and ‘competition on the merits,’ with the objectives of the DMA proposal as given in the accompanying explanatory memorandum. Just as the dual competition model espoused by early ordoliberals, the DMA proposal suggests a dual focus on establishing and protecting ‘contestable and fair’ markets in the digital economy. The expression ‘contestable market’ describes a market with low barriers, whereby the competitive threat of entry significantly constrains the incumbent (Jones & Sufrin, 2016, pp. 22–23). Conceptually, this notion can be traced back to the American economist William Baumol, whose contestable market theory assumes that in the case of easy ‘hit-and-run’ entry by potential competitors, even dominant firms will price competitively (Baumol, 1982). In contrast to the ordoliberal ‘complete competition’ model, reasoning along the lines of contestable market theory emphasises freedom of entry instead of market structure. This could be seen, for instance, in the Commission’s 2013 Syniverse/MACH decision, which approved a merger despite a highly concentrated market because it framed the latter along the lines of the contestable market theory.Footnote 6

At closer sight, however, references to ‘contestability’ in the explanatory memorandum of the DMA seem to be guided less by Baumol’s initial theory than by structuralist thinking in line with the ordoliberal model of ‘complete competition,’ as the lacking contestability in the digital economy is explained with the presence of ‘large platforms’ that ‘capture the biggest share of the overall value generated’ and are ‘entrenched in digital markets.’Footnote 7 The main problem is identified as the existence of a ‘small number of large providers of core platform services’ possessing ‘considerable economic power’ due to their ‘access to large amounts of data’ (recital 3 DMA proposal). Accordingly, the proposed obligations do not apply to all digital services but only to those qualifying as ‘core platform services’ (Art. 2(2) DMA proposal), whose categories are inspired by the business profiles of today’s Big Tech companies, such as ‘online intermediation services’ (think Amazon marketplace or Apple App Store), ‘online search engines’ (think Google), and ‘online social networking services’ (think Facebook). Tellingly, the scope of the DMA is further limited to those service providers that fulfil the three criteria for designating an undertaking as a so-called ‘gatekeeper,’ namely having a significant impact on the internal market, providing an important gateway to reach end-users, and enjoying an entrenched and durable position (Art. 3(1) DMA proposal). Moreover, the size-based thresholds for establishing the presumption that an undertaking meets these criteria (Art. 3(2) DMA proposal) have been selected in such a way as to ensure that primarily US-based Big Tech firms will be captured (Offergeld, 2021). The conceptual focus on powerful gatekeepers with entrenched positions that endanger the independence of SMEs corresponds to the ‘complete competition’ framework held by early ordoliberals. This is comparable to the conceptual role played by the legal concept of firms with ‘paramount significance for competition across markets’ in the updated German Competition Act (GWB).

Turning to the second part of the DMA’s objective to establish ‘contestable and fair markets,’ it must be noted that the concept of ‘fairness’ is often applied ambiguously. While EU competition law usually uses the term when referring to the ‘as efficient competitor test,’ whereby fairness means that the rules should ensure that an equally efficient competitor is not excluded from the market by the anti-competitive behaviour of dominant undertakings, most observers associate it with the protection of smaller competitors (Jones & Sufrin, 2016, p. 28). As noted, the ordoliberal paradigm of ‘competition on the merits’ is already well established under Art. 102 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) case law (Schinkel & LaRocuhe, 2014). The emphasis on firms competing based on their superior performance, as expressed in the EU legal doctrines related to a dominant firm’s ‘special responsibility’ and its obligation to grant access to an ‘essential facility’ under Art. 102 TFEU, might be considered a reference for defining whether conduct by a gatekeeper is ‘fair’ or not (Pera, 2022). If the term is operationalised along those lines, it will align the DMA with the ordoliberal elements in the case law.

The DMA imposes two main sets of obligations on gatekeepers, contained in Arts. 5 and 6 DMA proposal. Both apply directly, but the obligations in Art. 6, unlike those in Art. 5, can be further specified. Many of these obligations intended to create fair competition can be understood through the lens of ‘competition on the merits,’ like the prohibition on using data of business users to compete against them (Art. 6(2) DMA proposal), the prohibition on self-preferencing in ranking (Art. 6(5) DMA proposal), the obligation to allow interoperability (Art. 6(7) DMA proposal), and various obligations to provide data access and data portability (Art. 6(10, 6(11), and 6(12) DMA proposal). To illustrate, these legal obligations imply that in the future, Amazon cannot use data it collects from merchants in its role as an online marketplace to compete against them as a retailer, Google cannot treat its shopping services more favourably in the ranking of search results, Apple cannot restrict Spotify from accessing Apple’s voice assistant Siri when it does allow its music app to integrate with Siri, and Google cannot outright refuse the provider of a rival search engine access to its query data (Belloso, 2022). These are all obligations that envision a more competitive marketplace with independent players, a level playing field, and universal adherence to externally given rules of the game.

Applying the ordoliberal understanding of Leistungswettbewerb to the digital economy has already impacted recent case law and might thus foreshadow how the DMA obligations will be applied. Take, for instance, the Court’s argument in Google Shopping that a ‘system of undistorted competition can be guaranteed only if equality of opportunity is secured as between the various economic operators’ (para. 180),Footnote 8 which aligns well with the DMA and the ordoliberal idea of a fair competition game between independently acting economic entities. Tellingly, the notion of ‘competition on the merits’ occurs 17 times in this judgment. Similar terminology appears in the DMA, which argues that the comprehensive set of rules for ensuring fairness in the digital sector ‘will allow businesses to thrive on the merits of their abilities.’Footnote 9 Emphasising ‘equality of opportunity’ and ‘merits’ of competitors, as opposed to consumer welfare (e.g., lower prices brought about by the economies of scale of a monopolist), is an apparent deviation from the previous ‘More Economic Approach’ of the Commission (Schmidt & Wohlgemuth, 2010), but in line with ordoliberalism.

Echoing the third element of early ordoliberal competition thinking, the explanatory memorandum justifying the proposed DMA rules does not limit itself to the economic implications of the critical role of online platforms in digital markets but also emphasises their political and societal implications. By ensuring contestability and fairness in digital competition, the Commission hopes not only to increase ‘consumer choice,’ ‘efficiency,’ and ‘competitiveness of industry’ but to ‘enhance civil participation in society.’ It also explicitly refers to the ‘importance of ensuring a level playing field that supports essential values such as cultural diversity and media pluralism.’Footnote 10 In addition to the explanatory memorandum, the legal part of the DMA proposal likewise references the ‘negative societal and economic implications’ of the ‘weak contestability of core platform services’ (recital 6 DMA proposal). Remedying this situation through harmonised rules and obligations for gatekeepers would be ‘to the benefit of society as a whole’ (recital 32 DMA proposal). As in the case of early ordoliberals like Röpke and Rüstow, this broad conceptual basis for reasoning about the implications of competition leads, in practice, to a preference for SMEs. The report notes that SMEs are ‘very unlikely to qualify as gatekeepers’ and would therefore not be targeted by the proposed obligations. Instead of imposing additional burdens on them, the DMA rules would ‘level the playing field,’ allowing SMEs to expand throughout the internal market due to reduced barriers to entry and expansion. The Commission concludes that increased contestability in the digital economy would ultimately lead to a welfare increase of EUR 13 billion.Footnote 11

From the perspective of the fourth and fifth element in the ordoliberal competition model – an activist competition policy outlook and an adherence to the rule of law criteria – the proposed DMA is particularly interesting, as it not only aims to foster administrability but, in doing so, also departs from a discretion-based model of enforcing substantive law (Lindeboom, 2022, p. 72, fn. 91). Clearly, the DMA envisions a regulatory regime that affects the behaviour of gatekeepers already ex-ante, and, ideally, does not require lengthy proceedings, as the competition law practice of the past decade has shown that individual cases often take much too long to be solved to correct anti-competitive behaviour in fast-moving digital markets. As noted in the proposal: ‘The gatekeepers should ensure the compliance with this Regulation by design’ (recital 58 DMA proposal). This legal set-up of the DMA, which has been described as ‘introducing a layer of asymmetrical pro-competition ex-ante regime that should affect the conduct of the designated gatekeepers on an ongoing basis’ (Vezzoso, 2021, p. 405), aligns with the emphasis of early ordoliberals on actively shaping the standard behaviour and the expectations of the business community in such a way as to increase overall competitive intensity. It also overlaps with the continental legal tradition represented by the ordoliberal rule of law ideal described above, emphasising detailed codified rules rather than litigation (Dyson, 2021, p. ix).

For at least three reasons, however, the DMA is problematic from an ordoliberal rule of law perspective. First, the regulatory regime designed by the DMA goes beyond competition law in the narrow sense, also touching upon issues such as data protection and industrial policy, whose increased relevance in the past years points to potential trade-offs in the implementation of the rules that might hamper the system’s effectiveness and adherence to the rule of law (Stucke Forthcoming). This intermingling of policy fields is also reflected on an institutional and personal level, as epitomised in the person of Margrethe Vestager, who is not only the current Commissioner for Competition but, as an ‘Executive Vice-President,’ also bears responsibility for chairing the Commissioners’ Group on a ‘Europe Fit for the Digital Age’ and for co-leading a strategy for the EU’s industrial future. The current trend in the digital age to task enforcers to arbitrate between different objectives might open the door to capture (Petit & Schrepel, 2022, p. 22), which had been the prime fear of early ordoliberals.

Secondly, there are open questions about the procedural aspects related to the designation of undertakings as ‘gatekeepers.’ As alluded to above, the political battles about the specific elements flowing into the definition of a gatekeeper and the precise numbers behind the size-based thresholds suggest that European politicians were driven by the desire to target the US-based GAFAM companies, thereby potentially mixing ideas of fair competition with protectionist motives. Similarly problematic is the legal situation once an undertaking has been designed as a gatekeeper under the DMA regime. The Commission must review whether gatekeepers continue to satisfy the relevant criteria at least every three years and whether new undertakings meet the requirements yearly (Art. 4(2) DMA proposal). Three years can be a (too?) long time in the digital economy, which is often characterised as a market with ‘Schumpeterian’ dynamics (Robertson, 2017, p. 132). To ensure swifter enforcement of the DMA in fast-moving digital markets, it would be better to involve national authorities with their existing expertise in digital markets, analogous to the cooperation in the European Competition Network (Gasparotti, et al., 2021, p. 4). Moreover, even if an undertaking does not meet the size-based thresholds but satisfies the theoretical criteria (in Art. 3(1) DMA proposal), the Commission can designate a gatekeeper by conducting an additional market investigation, which will be based on myriad factors whose relative relevance is not entirely clear (Art. 3(8) DMA proposal). It can also designate a gatekeeper if it is foreseeable to enjoy an entrenched and durable position in the ‘near future’ (Art. 17(4) DMA proposal). These procedural problems are already foreshadowed in the current cases targeted at Big Tech (Lindeboom, 2022).

Lastly, the DMA documents show a clear desire to integrate large Tech firms in implementing the rules. For instance, both the prohibition on self-preferencing in ranking and the obligation to provide practical portability of data are gatekeeper obligations included in Art. 6 of the DMA proposal, which means they are susceptible to being further specified by way of a regulatory dialogue between the Commission and the gatekeepers (Vezzoso, 2021, p. 395, fn. 18), intended to ‘tailor’ the obligations and ‘ensure their effectiveness and proportionality’ (recital 33 DMA proposal). In another part of the proposal, the possibility of a regulatory dialogue is said to ‘facilitate compliance’ by gatekeepers (recital 58 DMA proposal). Partly, this might reflect the so-called ‘better regulation’ principles, which are increasingly spreading in EU law in general (Mödinger, 2020). Alarmingly from an ordoliberal perspective, however, this also seems to indicate a turn to a novel form of ‘participatory antitrust’ (Bethell, et al., 2019). This concept assumes that cooperation between governments, competition authorities, and industry will lead to better analytical frameworks and institutions conducive to digital innovation and is mainly popularised by the French economist Jean Tirole, who was one of the main speakers at the Commission’s inaugural conference that started the EU’s regulatory reform process (Küsters, 2022a, p. 82). Integrating powerful undertakings in applying the rules intended to control them certainly clashes with the early ordoliberal idea of a ‘strong state’ above vested interests that can guarantee independent and objective enforcement. It might even exacerbate the trend towards ‘counter-expertise’ that started with the Commission’s ‘More Economic Approach’ in the early 2000s (Schwalbe, 2009), with the only change being that the well-paid advisors questioning the Commission’s decisions will no longer be Industrial Organisation economists but computer scientists. Admittedly, this problem reflects, more generally, the vast inequalities in know-how and technical infrastructure between enforcers and economic agents in the digital age, which results from the immense wages offered and profits generated by GAFAM.

4 Competition policy and state control in China

China is a relative newcomer to the international competition law scene, having established an Anti-Monopoly Law (AML) only in 2007.Footnote 12 The law’s coverage resembles the three-pillar structure of European competition law, targeting anti-competitive agreements, monopolies, and mergers (Emch & Hao, 2007). Since 2018, China has possessed a single national competition authority, the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR), which replaced the initially divided enforcement structure (Ng, 2018, pp. 12–14). Despite these similarities, the specific rules of the AML and the institutional system for enforcing them represent a unique adaptation enacted as part of the gradual, partial liberalisation of the economy (Svetiev & Wang, 2016, pp. 187–188, 192–194). Since the 1970s, Chinese economic thought increasingly parallels that of the remaining world (Feng, et al., 2017, p. 221), not least due to an unlikely alliance between Chinese reformers and Western economists (Gewirtz, 2017). The following analysis restricts itself to the critical characteristics of the AML, focusing on the underlying economic ideas and the changes during the ‘tech crackdown.’

At first sight, the ordoliberal model of ‘complete competition’ seems to be echoed in the AML’s objective to formulate rules that help establish and protect a ‘sound market network which operates in an integrated, open, competitive, and orderly manner’ (Art. 4 AML) and in its heavy reliance on market shares for policy guidance (Arts. 18, 19, 27(1) AML). During a 2013 conference, Chinese officials tasked with enforcing the new anti-monopoly rules acknowledged that they focused on ‘static competition factors, such as simply expanding or maintaining the number of competitors in a particular market, rather than considering longer-term effects on innovation and consumer welfare’ (Ohlhausen, 2013, p. 2). A review of all published merger decisions until 2016 found that market share, market concentration, and market entry were the key three factors when evaluating a proposed merger (Ng, 2018, pp. 34–37), not its economic effects. In one of the most explicit expositions of Chinese antitrust reasoning, the 2019 Finisar acquisition decision warned of post-merger competition problems since ‘the number of competitors would be reduced from 3 to 2,’ thereby increasing the potential for collusion (Ju & Lin, 2020, p. 232).

This tendency to emphasise market structure, as opposed to actual market behaviour, has been further strengthened by recent cases decided during the ‘techlash.’ Some commentators even suspected a new form of ‘Ordocommunism’ when the Chinese government justified its $2.8bn antitrust fine for Alibaba in April 2021 with the ‘purification of the industry environment’ and ‘strong defence of fair competition.’Footnote 13 In addition to references to necessary ‘purification,’ this structural reasoning is typically reflected in semantics about an ideal type ‘regular market order.’ For instance, in March 2021, officials imposed penalties on leading community group-buying platforms owned by, amongst others, China’s ride-hailing giant Didi and e-commerce platform Pinduoduo, for improper below-cost pricing that ‘disrupted market order’ by squeezing out competitors – echoing the structuralist concerns of the ‘complete competition’ model. The Chinese antitrust actions against large Tech companies must also be seen as part of a larger plan of the government to prevent ‘the disorderly expansion of capital’ (Marco Colino, 2022, p. 219). Overall, the predominantly, albeit not exclusively (Sokol, 2013, p. 25), structuralist approach for detecting potential violators of orderly markets in China echoes Eucken’s vision of a strong state tackling any forces ‘whose activity disrupted market competition’ (Rahtz, 2017, p. 85).

Turning from the static to the behavioural perspective, the AML regulates that those undertakings holding a dominant position on the market may not abuse such position to ‘eliminate or restrict competition’ (Art. 6 AML), which includes a prohibition of differential prices among trading counterparts ‘on an equal footing’ (Art. 17(6) AML). Art. 7 AML specifies that even state-controlled undertakings must ‘do business according to law, be honest, faithful and strictly self-disciplined’ – all characteristics that align with the ordoliberal vision of a rule-based economy guided by the ‘belief in personal responsibility’ and the ‘virtues of discipline, honesty, and reliability’ (Dyson, 2021, p. 114). Similarly, Art. 11 AML stipulates, in ordoliberal-sounding rhetoric, that industry associations ‘shall tighten their self-discipline’, ensure that all their members engage only in ‘lawful competition,’ and maintain the ‘market order in competition’ (Fox, 2008, pp. 179–180, 191–192). In line with this, the recently proposed guidelines for the platform economy define ‘fair competition’ as ‘treating market players on an equal footing without discrimination’ (Art. 3(1) Guidelines).Footnote 14 Crucially, this behavioural perspective is reflected in the strong reliance on behavioural remedies in merger reviews, like non-discrimination commitments (Hanley, 2022; Ng, 2018, pp. 42–56), which is an illuminating divergence from Western jurisdictions, which predominantly rely on structural remedies. In the decision against Alibaba during the recent ‘techlash,’ Chinese officials continued to resort to behavioural instructions to ensure compliance, including obligations regarding using algorithms (Marco Colino, 2022, p. 225).

Still, for early ordoliberals like Böhm, Leistungswettbewerb was not just a narrow competition law concept relevant to experts but a broader societal vision whose legitimacy rested on its popular appeal and a ‘fundamental decision’ (Gesamtentscheidung) for an economic constitution tilted towards competition (Böhm, 2017b). According to Maureen Ohlhausen, a well-known US Federal Trade Commissioner, Chinese antitrust and government officials indicate a ‘serious interest in promoting competition as a societal value’ (Ohlhausen, 2013, p. 2). The most important regulatory reform in this respect is the ‘Fair Competition Review’ (FCR) system set up in 2016, whereby policy proposals and existing regulations by government agencies must be reviewed so as to identify regulations that restrict the principle of competition (Ju & Lin, 2020, pp. 222–223). Nevertheless, there is a relatively mild level of AML enforcement against state-owned enterprises, or SOEs (Emch, 2008, p. 9; Wang and Emch, 2013, p. 267 f.), which have enjoyed a special legal status from the very beginning and continue to play, in certain sectors, both a commercial and a regulatory role (Fox, 2008). Together with the sometimes drastic interventions by the relevant authorities, including partial price-fixing and cartel consolidation (Emch & Liang, 2013, p. 5), this shows that the role ascribed to Leistungswettbewerb in the Chinese economy is not as all-encompassing as early ordoliberals would have hoped.

When aiming to evaluate whether Chinese competition law goes beyond narrow economic objectives, one can turn to Art. 1 AML, which lists the goals of the regulation as ‘preventing and restraining monopolistic conducts, protecting fair market competition, enhancing economic efficiency, safeguarding the interests of consumers and the interests of the society as a whole, and promoting the healthy development of the socialist market economy.’ Moreover, as stipulated in Art. 27 of the AML, the review of proposed mergers should be conducted based on economic factors like market concentration but also the merger’s impact ‘on the development of the national economy.’ As these provisions suggest, and as an in-depth review of critical cases has confirmed, Chinese competition policy follows various policy objectives without necessarily according to them any primacy, thus adopting a ‘flexible balancing approach’ to deciding cases (Svetiev & Wang, 2016, p. 191). Non-competition factors like employment impact and the creation of globally competitive champions play a particular role in Chinese merger control (Sokol, 2013, pp. 22–23).

While ordoliberals argued that increased competition would result in broader societal benefits that allowed for the inclusion of public interest factors, Chinese officials are mainly concerned with furthering state interests rather than public interests (Ng, 2020). A practitioner survey of antitrust lawyers across multiple jurisdictions has revealed the direct intervention of other parts of the Chinese government within the merger review process, concluding that these other institutional actors have ‘significant influence in putting certain conditions on the merger approval not based on antitrust economics and may require concessions by the merging parties that have nothing to do with competitive effects’ (Sokol, 2013, p. 35 (emphasis added)). Even when ordoliberals allowed for interventions into the property rights of companies, they clarified that this should not extend to purposes transcending the protection of competition, such as protecting employment (Möschel, 1980). In other words, even though both ordoliberal and Chinese competition thinking stress antitrust factors beyond increasing economic efficiency, there remains a contrast in the type of public interests to be pursued.

The fourth element in the ordoliberal competition regime is an activist, wide-ranging enforcement approach. By July 2019, the responsible agencies had completed 179 cases involving monopoly agreements and 61 cases involving abusing a dominant position, with fines totalling more than $1.7 billion (Ju & Lin, 2020, p. 221). Especially China’s merger control and enforcement practice have reached a stage of maturity (Emch, et al., 2016), which is notable from an ordoliberal perspective, as merger control promises to prevent economic power from arising in the first place. Crucial examples of the Chinese competition authorities being vigilant and active enforcers in the digital age are the Qualcomm case of 2015, in which the respective company was fined $975 million for unfairly high selling prices, tying conduct, and the imposition of unreasonable conditions in the chips market (Ng, 2018, p. 88), and the Alibaba decision from April 2021, whose penalty was even three times higher in absolute terms (Marco Colino, 2022, p. 218). The delegation of enforcement power to provincial antitrust authorities in 2019, which previously could not initiate an AML investigation without authorisation, further strengthened the active enforcement of the rules (Ju & Lin, 2020, p. 230).

A vital element of the activist ordoliberal approach identified above has been its preference for ex-ante promotion of competition and dissolution of economic power structures instead of mere ex-post abuse control. In that respect, it is noteworthy that the FCR system mandates ex-ante competitive assessments of policy measures and thereby complements the AML, establishing a two-pillar competition policy in China (Su, 2016). This regulatory reform includes a list of 18 ‘don’ts,’ which specify prohibited competition-restricting policy types like preferential policies and unreasonable and discriminatory criteria for market entry and exit. This list has a ‘strong flavour of a per se rule’ (Ju & Lin, 2020, p. 223), in line with ordoliberal preferences (Küsters & Oakes, 2022). Substantially, the emphasis on market entry and the detailed ‘18 don’ts’ resemble the dual objective of contestable and fair markets in the DMA draft regulation, which envisages gatekeepers to comply with ‘the eighteen do’s and don’ts’ (Vezzoso, 2021, p. 393) comprehensively listed in Arts. 5 and 6 DMA proposal. In the system’s first two years alone, 430,000 Chinese policy proposals were reviewed under the FCR system, of which more than 2,300 were subsequently revised to allow for more competition (Ju & Lin, 2020, p. 222).

The ‘techlash’ of 2021 represents the latest step in this trend towards activist enforcement and, where possible, increased ex-ante regulation of competitive markets in Chinese competition policy. On February 7, 2021, SAMR published the above-mentioned final guidelines for the platform economy sector, which aim to ‘promote the well-regulated, orderly, innovative and healthy development of the platform economy industries’ (Art. 1 Guidelines). On October 23, 2021, China’s national legislature published a draft of an amendment to the AML, emphasising that undertakings shall not exclude or restrict competition by abusing the advantages in data and algorithms, technology, and capital and platform rules. From a legal point of view, it would have been preferable to include key features of the digital economy, like network effects or consumer lock-in, in the revised law without limiting their applications to just the Internet sector (Ju & Lin, 2020, p. 237), but the fact that the latter is now explicitly named signals the political leadership’s wish to rein in the power of Chinese digital giants. Prominent early examples of this shift in enforcement priorities were Alibaba’s $2.8 billion antitrust fine for exclusionary practices in April 2021 and, a couple of months later, SAMR’s decision to fine Meituan, an online food delivery platform provider, $534 million for abusing its dominant position.

Fifthly, one must address the legal-procedural aspects deeply embedded in the rule of law tradition of European competition law regimes. Considering the strong but ultimately not rule-bound role of the Chinese antitrust bureaucracy, which acts less as an objective economic expert or independent judge but rather as a political planner (Arts. 15, 28, 46 AML), a vital difference to ordoliberalism emerges. Tellingly, Chinese regulators have used the AML also as an instrument for price control, market stabilisation, and even foreign policy (Zhang, 2021, chs. 1, 2, and 5). Since other government ministries must agree to a merger approval, internal negotiations about the relevant ‘non-competition factors’ often prolong the state of legal uncertainty by several months (Sokol, 2013, p. 35). While there are deadlines for the length of review procedures, these can be effectively overridden by the Chinese authorities requiring parties to submit additional information (Emch, 2009, p. 907). Moreover, ‘where only the result – and not the manner – of balancing various policy considerations in enforcement is disclosed by the authority, this leaves the impression of uncontrolled discretion’ (Svetiev & Wang, 2016, p. 221), which diverges from an ordoliberal rule-bound regime. Partly, this discretionary power reflects that the AML contains several ‘catch-all clauses’ and that in the Chinese legal order, the administrative body that has issued a norm retains the authority to interpret it, not the judiciary (Emch, 2008, pp. 10–13).

Besides the frequent, discretionary, and state-led consideration of non-competition factors in enforcement, further violations of the rule of law criteria in Chinese competition policy emerge concerning the unique advantages often granted to SOEs, alleged discrimination against foreign companies, and the general lack of transparency and due process in the enforcement process (Ng, 2018, pp. 4–16). There are numerous reports of Chinese antitrust officials pressuring companies into an admission or cooperation (Zhang, 2021). The exclusion of foreign legal counsel from merger review proceedings denies companies the right to adequate legal representation (Ng, 2018, p. 15). In these proceedings, substantive concerns are typically conveyed orally, not in writing, which increases legal uncertainty (Emch, et al., 2016). Moreover, the burden of proof seems too high for plaintiffs seeking redress for antitrust violations through the Chinese courts (Emch & Liang, 2013). Most published administrative decisions lack a detailed treatment of the parties’ arguments, the evidence considered, and the reasoning behind the final decision (Ju & Lin, 2020, p. 234; Wang and Emch, 2013, pp. 254–256). For instance, the guidelines on what constitutes illegal ‘concerted practice’ are, according to practitioners, ‘worryingly unclear and possibly too intrusive for market players’ (Emch, 2011, p. 21). Even when standard theories of competitive harm are applied, empirical evidence and structured analysis to support the adoption of a particular theory are generally lacking (Ng, 2018, p. 37).

Finally, there is a lack of consistency across antitrust decisions (Ju & Lin, 2020, pp. 225, 234–236). At least partly, slow procedure and minimalist decisions might reflect the fact that the Chinese competition agencies are understaffed (Ju & Lin, 2020, p. 237) and lack independence and an esprit de corps (Emch & Hao, 2007, p. 21), which encourages informal negotiations and weakens antitrust officials’ voice vis-à-vis political ministries. More generally, however, this must be seen as a feature, and not a bug, of a highly illiberal country ruled by a powerful Communist Party with discretionary powers and interests that can change quickly – which differs from the ordoliberal understanding of a society governed by rules that apply equally to all. For instance, when Chinese antitrust officials blocked the merger in Coca-Cola/Huiyuan (2009), international competition lawyers were puzzled by the absence of a market definition and the unclear criteria for establishing dominance and anti-competitive effects, which suggest that the desire to protect a well-known domestic brand against a foreign company had taken priority over economic methodology.

During the past years of increased enforcement, the picture has remained mixed. On the one hand, the new FCR system is a promising first step towards more consideration of the rule of law criteria, as it includes a catch-all provision stipulating that ‘no regions or departments shall promulgate policy measures that derogate the legal rights and interests or increase the obligations of business operators without legal basis’ (Su, 2016). The new platform guidelines stipulate that the antitrust agencies shall supervise ‘lawfully, scientifically and high-effectively’ (Art. 3(2) Guidelines). In recent cases, Chinese antitrust officials have in fact imposed remedies based on standard economic theories of competition harm as also applied in other jurisdictions like the EU (Ju & Lin, 2020, p. 232), and the targeting of domestic Tech companies questions the usual protectionist narrative of outside observers. On the other hand, this increased enforcement against Internet companies has further exacerbated the trend of limited judicial scrutiny of administrative decisions (Marco Colino, 2022, p. 225). Moreover, the planned AML amendments to sanction digital giants will increase maximum fines, impose individual liability, and give the relevant agencies greater flexibility to suspend the statutory timeline (Hanley, 2022). ‘Given the lack of checks and balances in Chinese antitrust enforcement,’ the legal scholar Angela Zhang comments, ‘this considerable enhancement of the sanctioning power under the AML will no doubt afford the administrative enforcement agency even greater discretion’ (Zhang, 2021, p. 222). In other words, the impression of too much discretion in Chinese competition policy echoes some of the procedural concerns regarding the DMA.

5 Conclusion

This paper compared the core ideas of the early Freiburg School on competition and the rule of law with current reforms and trends in EU and Chinese competition law that are motivated by the digital revolution. To do so, the first section defined an ideal type conception of early ordoliberal competition thought through five elements: structuralist thinking surrounding the atomistic market model of ‘complete competition,’ ethical behavioural standards of competition related to the idea of socially beneficial ‘competition on the merits,’ extra-economic advantages of competition in the social and political sub-orders, as suggested by ordoliberalism’s normative underpinnings and its concept of the ‘interdependence of orders,’ the recommendation of activist, ex-ante policies targeted at concentrated economic power, and the rule of law criteria, especially as they relate to the independence of the competition authority and procedural fairness.

The following section compared this ideal type with critical elements in the Commission’s recently proposed Digital Markets Act. The economic thinking behind the DMA’s impetus to establish ‘contestable and fair markets,’ despite some ambiguity in these terms, aligns well with ordoliberalism’s structural reasoning about powerful ‘gatekeepers’ and ethical competition on a level playing field. The extra-economic benefits of having more market players are described in accompanying documents, echoing the Freiburg School’s sociological strand. In line with the ideas of early ordoliberals, the rules complement the lengthy case law procedure with an ex-ante regime focused on regulation by design. Still, the potential trade-offs with other policy fields, like privacy and industrial policy, the unclear way in which the list of gatekeepers is established and updated, and the planned involvement of Big Tech firms in the regulatory dialogue mean that the most significant deviation from ordoliberalism can be seen in the DMA’s procedural aspects.

A similar picture emerged when turning to the Chinese Anti-Monopoly Law and the latest changes to its content and enforcement. Illuminating overlaps with ordoliberalism arise in the Chinese officials’ structuralist antitrust approach, their focus on behavioural remedies, and their sense of non-economic factors that might matter in an antitrust setting. The activist enforcement of the competition rules, especially during the recent ‘techlash,’ and their complementation with a set of ex-ante obligations (‘don’ts’) likewise aligns with the preferences of early ordoliberals and the DMA. However, it was shown that the responsible agency is not independent and repeatedly violates several rule of law criteria. Overall, the Chinese competition law system shows relatively more parallels to the ordoliberal ideal type in its substantive rather than its procedural dimensions. Nevertheless, these similarities, which mainly relate to the ‘law in the books,’ should not be overstated, as the supposedly pro-competitive intent of the proposed rules for the digital economy are implemented, applied, and enforced in an illiberal society with a powerful political party at its centre – and these are elements that precisely an ordoliberal perspective, which emphasises the interdependence of the legal order with the broader economic and political system, cannot ignore.

Overall, the arguments and examples put forward in this paper contribute to two main discussions in the literature. First, the emphasis on the rule of law aspect is timely and relevant for current competition law practice. Tellingly, Böhm’s trust in the capabilities of an antitrust bureaucracy, to which he once belonged in Weimar times, quickly changed after the war and he became more sceptical (Nörr, 1994, p. 158). As if confirming Böhm’s fears, the new regulatory proposals in Europe and China suggest that competition officials may be failing to rely on sound evidence, protect due process, tailor remedies to the underlying harm, and avoid discrimination on non-competition grounds when dealing with the digital economy (Taladay & Ohlhausen, 2022). Thus, reformers and enforcers should select ‘gatekeepers’ based on objective data. From an ordoliberal perspective, relying on indicators that go beyond economic criteria and include political power (Baum and Messer Forthcoming) seems a promising path.

Secondly, the identified lack of thinking about procedural rules and actual implementation also characterises the flourishing literature on ordoliberalism and its legacy. While many significant substantive parallels and differences have been drawn in recent years between ordoliberal theory and certain policy areas at the national and European levels, for example, regarding competition policy or central banking, the role of related legal mechanisms based on the rule of law – and their normative advantages in terms of freedom and human rights – has been ignored. Based on the arguments put forward in this paper, ordoliberal literature and ideas could contribute to the currently emerging research agenda on the nexus between democracy, Big Tech, and competition law (Robertson, 2022), whose goal is to explore how democracy-related harm could extend existing theories of competitive harm in data-driven digital markets.

In this way, it becomes clear that ordoliberalism has not really ‘gone China’ – this, it is stipulated, would require introducing a whole set of procedural safeguards adapted to the demands of the digital age. In this respect, the fate of the Unirule Institute of Economics is telling. It was ordered to be shut down in 2019 after a long series of suppression, harassment, and interruptions. Many Unirule scholars are banned from publishing or writing for public news outlets, and those affiliated with government-backed organisations had to sever ties with Unirule. Nowadays, China is a highly illiberal country, and the struggle for power brought about by the digital revolution, both in the economic and the political realms, means that the Chinese Communist Party is increasingly intolerant of different voices – including ordoliberal ones.

Notes

See, e.g.: Case T-612/17 Google and Alphabet v. Commission (Google Shopping) ECLI:EU:T:2021:763; Case C-252/21 Facebook v. Bundeskartellamt [2021] OJ C320/16; European Commission, Apple App Store (Case AT.40,437); European Commission, Amazon Marketplace (Case AT.40,462).

‘Ordoliberalism goes China! Peter Jungen übergibt das mit @Lars_Feld, Zhu Min und Zhou Hong herausgegebene Buch an Präsident Xi.’ Eucken Institute (@EuckenInstitut), Twitter (9.12.2019).

See, for instance: Judgment of the Court of 4 June 2009, T-Mobile Netherlands BV, KPN Mobile NV, Orange Nederland NV and Vodafone Libertel NV v Raad van bestuur van de Nederlandse Mededingingsautoriteit – T Mobile Netherlands, Case C-8/08, ECLI:EU:C:2009:343, para. 38; Judgment of the Court of 21 February 1973, Europemballage Corporation and Continental Can Company Inc. v Commission of the European Communities – Continental Can, Case 6–72, ECLI:EU:C:1973:22, para. 26.

See, for instance: Judgment of the Court of 13 February 1979, Hoffmann-La Roche & Co. AG v Commission of the European Communities – Hoffmann-La Roche, Case 85/76, ECLI:EU:C:1979:36, paras. 90 f.

Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Contestable and Fair Markets in the Digital Sector (Digital Markets Act), COM(2020) 842 final.

See the references to the ‘contestable Bertrand market’ in: Commission Decision of 29 May 2013, Case COMP/M.6690, Syniverse/Mach – C(2013) 3114 final, e.g. paras. 214 f.

Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Contestable and Fair Markets in the Digital Sector (Digital Markets Act), COM(2020) 842 final, p. 1.

Judgment of the General Court (Ninth Chamber, Extended Composition) of 10 November 2021, Google LLC, formerly Google Inc. and Alphabet, Inc. v European Commission, Case T-612/17 – Google Shopping, ECLI:EU:T:2021:763.

Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Contestable and Fair Markets in the Digital Sector (Digital Markets Act), COM(2020) 842 final, p. 11.

All quotes taken from: Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Contestable and Fair Markets in the Digital Sector (Digital Markets Act), COM(2020) 842 final, p. 1 and fn. 2.

All quotes taken from: Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Contestable and Fair Markets in the Digital Sector (Digital Markets Act), COM(2020) 842 final, p. 10.

Anti-Monopoly Law of the People’s Republic of China, adopted at the 29th Meeting of the Standing Committee of the Tenth National People’s Congress on August 30, 2007 (effective Aug. 1, 2008), available at: http://english.mofcom.gov.cn/article/policyrelease/Businessregulations/201303/20130300045909.shtml (accessed: 25.5.2022).

‘Ordocommunism at last.’ Benjamin Braun (@BJMbraun), Twitter (10.4.2021).

SAMR, Draft Anti-Monopoly Guidelines for the Platform Economy Industry (November 10, 2020), English translation available at: https://www.anjielaw.com/en/uploads/soft/210224/1-210224112247.pdf (accessed: 6.6.2022).

References

Bak-Coleman, J. B., Alfano, M., Barfuss, W., Bergstrom, C. T., Centeno, M. A., Couzin, I. D., et al. (2021). Stewardship of global collective behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(27), e2025764118.

Banasiński, C., & Rojszczak, M. (2022). The role of competition authorities in protecting freedom of speech: The PKN Orlen/Polska Press case. European Competition Journal, 18(2), 424–457.

Baum, I., & Messer, D. L. (Forthcoming). Can the Next Amazon or Facebook Be Controlled Before It Becomes Too Powerful. University of Memphis Law Review, 52, 1–45.

Baumol, W. J. (1982). Contestable markets: An Uprising in the theory of industry structure. American Economic Review, 72(1), 1–15.

Behlke, R. (1961). Der Neoliberalismus und die Gestaltung der Wirtschaftsverfassung. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

Belloso, M. (2022). The EU Digital Markets Act (DMA): A Summary. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–4.

Bethell, O. J., Baird, G. N., & Waksman, A. M. (2019). Ensuring innovation through participative antitrust. Journal of Antitrust Enforcement, jnz024. https://doi.org/10.1093/jaenfo/jnz024.

Böhm, F. (1933). Wettbewerb und Monopolkampf. Eine Untersuchung zur Frage des wirtschaftlichen Kampfrechts und zur Frage der rechtlichen Struktur der geltenden Wirtschaftsordnung. Berlin: Carl Heymanns.

Böhm, F. (1937). Die Ordnung der Wirtschaft als geschichtliche Aufgabe und rechtsschöpferische Leistung. Stuttgart; Berlin: W. Kohlhammer.

Böhm, F. (1966). Privatrechtsgesellschaft und Marktwirtschaft. ORDO: Jahrbuch für die Ordnung von Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, 17, 75–151.

Böhm, F. (2017a). Decartelisation and de-concentration: A problem for specialists or a fateful question? In T. Biebricher, & F. Vogelmann (Eds.), The birth of Austerity: German ordoliberalism and contemporary neoliberalism (pp. 121–136). London: Rowman & Littlefield Int.

Böhm, F. (2017b). Economic ordering as a problem of economic policy and a problem of the economic constitution. In T. Biebricher, & F. Vogelmann (Eds.), The birth of Austerity: German ordoliberalism and contemporary neoliberalism (pp. 115–120). London: Rowman & Littlefield Int.

Böhm, F., Eucken, W., & Großmann-Doerth, H. (2017). The Ordo Manifesto of 1936. In T. Biebricher, & F. Vogelmann (Eds.), The birth of Austerity: German ordoliberalism and contemporary neoliberalism (pp. 27–40). London: Rowman & Littlefield Int.

Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz (2022, February 21). Wettbewerbspolitische Agenda des BMWK bis 2025. 10 Punkte für nachhaltigen Wettbewerb als Grundpfeiler der sozial-ökologischen Marktwirtschaft. https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/0-9/10-punkte-papier-wettbewerbsrecht.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=6. Accessed 15 April 2022

Colomo, P. I. (2013). Review of: Pinar Akman, the Concept of abuse in EU Competition Law: Law and Economic Approaches, Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2012. The Modern Law Review, 76(2), 421–425.

Deutscher, E., & Makris, S. (2016). Exploring the Ordoliberal paradigm: The Competition Democracy Nexus. Competition Law Review, 11(2), 181–214.

Dold, M., & Krieger, T. (2019). The ‘New’ Crisis of the liberal order: Populism, socioeconomic imbalances, and the response of contemporary ordoliberalism. Journal of Contextual Economics – Schmollers Jahrbuch, 139(2–4), 243–258.

Dyson, K. H. F. (2021). Conservative liberalism, Ordo-liberalism, and the state: Disciplining democracy and the market. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Emch, A. (2008). The Antimonopoly Law and its structural shortcomings. GCP, 1, 1–14.

Emch, A. (2009). Das chinesische Antimonopolgesetz in der Praxis. Zeitschrift für Immaterialgüter Informations- und Wettbewerbsrecht, (12), 905–915.

Emch, A. (2011). The Antitrust enforcers’ New Year Resolutions. China Law & Practice, 20–24.

Emch, A., & Hao, Q. (2007). The New Chinese Anti-Monopoly Law - An Overview. eSapience Center for Competition Policy, 1–21.

Emch, A., & Liang, J. (2013). Private Antitrust litigation in China - the Burden of Proof and its Challenges. CPI Antitrust Chronicle, (1), 1–15.

Emch, A., Han, W., & Ingen-Housz, C. (2016). Merger Control in China: Procedural Rights. Procedural rights in Competition Law in the EU and China (pp. 101–128). Berlin: Springer.

Eucken, W. (2004). Grundsätze der Wirtschaftspolitik (7th ed.). Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Eucken, W. (2017). Competition as the Basic Principle of the Economic Constitution. In T. Biebricher, & F. Vogelmann (Eds.), The birth of Austerity: German ordoliberalism and contemporary neoliberalism (pp. 81–98). London: Rowman & Littlefield Int.

Ezrachi, A., & Stucke, M. E. (2016). Virtual competition: The Promise and Perils of the Algorithm-Driven Economy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Feld, L. P., Jungen, P., Min, Z., & Hong, Z. (Eds.). (2019). The Social Market Economy: Compatibility among individual, market, Society and State. Beijin: Citic Press.

Feng, X., Li, W., & Osborne, E. W. (2017). Classical liberalism in China: Some history and prospects. Econ Journal Watch, 14(2), 218–240.

Fox, E. M. (2008). An Anti-Monopoly Law for China - scaling the walls of Government Restraints. Antitrust Law Journal, 75(1), 173–194.

Gasparotti, A., Kullas, M., & Harta, L. (2021). Digital Markets Act – Durchsetzung und Verfahren. cepAnalyse, 15, 1–4.

Gerber, D. J. (1998). Law and Competition in Twentieth-Century Europe: Protecting Prometheus. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gewirtz, J. B. (2017). Unlikely partners: Chinese reformers, western economists, and the making of global China. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Giegold, S. (2022, May 4). Antitrust Pendulum Swinging Back. D’Kart - Antitrust Blog. https://www.d-kart.de/blog/2022/05/04/antitrust-pendulum-swinging-back/?utm_source=mailpoet&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=d-kart-news_1. Accessed 5 April 2022

Großmann-Doerth, H. (2008). Selbstgeschaffenes Recht der Wirtschaft und staatliches Recht. In N. Goldschmidt, & M. Wohlgemuth (Eds.), Grundtexte zur Freiburger tradition der Ordnungsökonomik (pp. 77–90). Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Hanley, B. (2022, February 3). China Antitrust Review 2021. DavisPolk Client Update. https://www.davispolk.com/insights/client-update/china-antitrust-review-2021. Accessed 27 May 2022

Hax, H. (2007). Wirtschaftspolitik als Ordnungspolitik - Das Leitbild der Sozialen Marktwirtschaft. KAS China Working Paper, 19, 1–8.

Hien, J., & Joerges, C. (Eds.). (2017). Ordoliberalism: Law and the rule of Economics. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

Hong, Y. (2020). Socialist political economy with chinese characteristics in a new era. China Political Economy, 3(2), 259–277.

Jones, A., & Sufrin, B. (2016). EU Competition Law: Text, Cases, and Materials (Sixth edition.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ju, H., & Lin, P. (2020). China’s Anti-Monopoly Law and the role of economics in its enforcement. Russian Journal of Economics, 6(3), 219–238.

Karl, R. E. (2017). The magic of concepts: History and the economic in twentieth-century China. Durham: Duke University Press.

Köhler, E. A., & Kolev, S. (2011). The Conjoint Quest for a liberal positive program: “Old Chicago”, Freiburg and Hayek. HWWI Research Paper, 109, 1–32.

Kolev, S. (2015). Ordoliberalism and the Austrian School. In C. J. Coyne, & P. Boettke (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Austrian Economics (pp. 418–444). Oxford University Press. Accessed 31 December 2021.

Kolev, S. (2017). Neoliberale Staatsverständnisse im Vergleich (2nd ed.). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Küsters, A. (2022a). Gestaltung des EU-Wettbewerbsrechts im digitalen Zeitalter: Ein quantitativer und qualitativer Vergleich von Konsultationsverfahren, Expertenbericht und jüngsten Reformvorhaben. Berlin: Peter Lang.

Küsters, A. (2023). Ordering ORDO: Capturing the Freiburg School’s Post-war Development through a text mining analysis of its yearbook (1948–2014). Economic History Yearbook, 64(1), 55–109.

Küsters, A. (2022b, June). The Making and Unmaking of Ordoliberal Language. A Digital Conceptual History of European Competition Law (PhD dissertation). University of Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main.

Küsters, A., & Oakes, I. (2022). Taming giants: How ordoliberal competition theory can address power in the digital age. Schmollers Jahrbuch – Journal of Contextual Economics.

Lee, P. (2018). Innovation and the firm. A New Synthesis. Standford Law Review, 70(5), 1431–1501.

Lenel, H. O. (1972). Zum Teerfarbenurteil und zur sogenannten Fusionskontrolle. ORDO: Jahrbuch für die Ordnung von Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, 23, 307–328.

Li, K. (2018). AI superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the new world order. Boston New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. (International Edition.).

Lindeboom, J. (2022). Rules, discretion, and reasoning according to Law: A dynamic-positivist perspective on Google Shopping. Journal of European Competition Law & Practice, 13(2), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeclap/lpac008.

Lynn, B. C. (2020). Liberty from all masters: The New American Autocracy vs. the Will of the people. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Makris, S. (2021). Openness and Integrity in Antitrust. Journal of Competition Law & Economics, 17(1), 1–62.

Marco Colino, S. (2022). The case against Alibaba in China and its wider policy repercussions. Journal of Antitrust Enforcement, 10(1), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1093/jaenfo/jnab022.

Miettinen, T. (2021). Ordoliberalism and the rethinking of liberal rationality. In A. M. Cunha, & C. E. Suprinyak (Eds.), Political Economy and International Order in Interwar Europe (pp. 269–295). Cham: Springer International Publishing. Accessed 4 March 2022.

Miksch, L. (1937). Wettbewerb als Aufgabe. Grundsätze einer Wettbewerbsordnung. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Mirowski, P., & Plehwe, D. (Eds.). (2009). The Road from Mont Pelerin: The making of the neoliberal thought collective. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Mödinger, M. (2020). Bessere Rechtsetzung. Leistungsfähigkeit eines europäischen konzepts. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Möschel, W. (1979). Die Idee der rule of law und das Kartellrecht heute: Am Beispiel der gezielten Kampfpreisunterbietung. ORDO: Jahrbuch für die Ordnung von Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, 30, 295–312.

Möschel, W. (1980). Wettbewerbsgesetz und Unternehmensentflechtung. ORDO: Jahrbuch für die Ordnung von Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, 31, 69–85.

Möschel, W. (1997). Die Unabhängigkeit des Bundeskartellamtes. ORDO: Jahrbuch für die Ordnung von Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, 48, 241–251.