Abstract

Can a lack of transitional justice contribute to democratic backsliding? This paper uses the case of Poland to argue that selective enforcement of transitional justice can be linked to democratic erosion. In doing so, the paper adjudicates between two theories of democratic backsliding. The first, advanced by Milan Svolik, argues that elite polarization drives erosion: when political candidates are ideologically far apart, citizens who strongly prefer one over the other may turn a blind eye to antidemocratic transgressions by their preferred candidate to prevent the competing candidate from winning. The second theory, presented by Nalepa, Vanberg, and Ciopris (NVC), describes an equilibrium where voters are uncertain whether the candidate they are dealing with is a closet autocrat or an ideological incumbent, but reelect him into office regardless. This theory posits that a closet autocrat is reelected into office because his first period actions are identical to those of an ideological incumbent. I argue that judiciary reforms in Poland reflect exactly the kind of incumbent actions that are consistent both with the actions of an ideological incumbent and with the actions of a closet autocrat. Using survey data from Poland, I find evidence of elite polarization, offering support for the first theory, but also find ample evidence of polarization in the electorate and of a belief structure supportive of the equilibrium from NVC. I present Hungary’s experience with transitional justice and the rule of law as a shadow case to illustrate similar dynamics to those taking place in Poland.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Can a lack of transitional justice contribute to democratic backsliding? Transitional justice (TJ) comprises the set of procedures designed by a country recovering from conflict or authoritarian rule to come to terms with its past (Kaminski et al. 2006). In addition to criminal trials of repressive agents of the former regime, TJ includes personnel TJ mechanisms, which include lustration and purges (Bates et al. 2020). Lustration vets candidates for public office for ties to the former authoritarian secret police, revealing previously-secret information. In contrast, purges remove from public office known collaborators of the ancien régime.

Authors of the two classical volumes that established the field of comparative democratization and regime transitions, The Third Wave of Democratization and Tentative Conclusions on Transitions from Authoritarian Rule, have been reluctant to advise democratizing states to engage in TJ. According to Samuel Huntington, “amnesty (…) is necessary to establish a new democracy on a solid basis;” further, “even if a moral and legal argument could be made for prosecution, this would fall before the normative imperative of creating a stable democracy” (Huntington 1993, 214). In the 1980’s, Philippe Schmitter and Guillermo O’Donnell warned “that the more brutal, inhumane, and extensive were the repressive actions, the more their actual perpetrators—the institutions involved and those persons who collaborated with them or supported them—feel threatened and will tend to form a bloc opposing any transition. Where they cannot prevent the transition, they will strive to obtain iron clad guarantees that under no circumstance will the ‘past be unearthed’; failing to obtain that, they will remain a serious threat to the nascent democracy” (O’Donnell and Schmitter 2013, 31–32). In an article published 2 decades later, Jack Snyder reiterated the risks of engaging in TJ: “the prosecution of perpetrators of atrocities according to universal standards risks causing more atrocities than it would prevent, because it pays insufficient attention to political realities” (Snyder and Vinjamuri 2004, 5).

What all of these authors seem to implicitly assume is that the costs of “doing nothing” are negligible. It is this assumption that this article calls into question. Poland and Hungary, the two post-communist countries that were slow to implement TJ, or adopted it half-heartedly, are also the ones leading the pack in backsliding into autocracy, though for entirely different reasons than those posited by Huntington, O’Donnell and Schmitter, and Snyder. I argue in this paper that a refusal to engage in TJ can endanger democratization and be used as a pretext for incumbent-led authoritarian backsliding. Specifically, using the example of Poland (and the shadow case of Hungary), I show that reluctance by the liberal governments in office since 1993 to engage in personnel TJ of the judiciary has provided their populist successors (PiS in Poland and Fidesz in Hungary) with an excuse to undermine judiciary independence and to use a broadly defined decommunization project to tighten their grip on power.

My explanation relies on a theory of authoritarian backsliding put forward in a paper by Nalepa, Vanberg, and Ciopris (NVC), who explain backsliding even in an environment where the electorate has a strong aversion to authoritarian politics and would prefer, all things considered, that the polity remain democratic. This model contrasts with Milan Svolik’s authoritarian backsliding theory, according to which, given a sufficiently high degree of elite polarization, voters prefer to retain in office an incumbent who undermines democracy as long as he is ideologically closer to them than a committed democrat would be. The NVC argument hinges on voters’ uncertainty about the type of incumbent they are facing. Because in the pre-electoral period, voters observe actions that are consistent both with the behavior of an ideological incumbent and a closet autocrat, they may elect the proverbial “wolf,” just “masquerading in sheep’s clothing,” for a second period in office.

In this article, I show that the actions of Polish incumbents fit the NVC model perfectly: both their moves to clear the judiciary of vestiges of the communist past and to staff key judiciary institutions with their supporters and to remove constitutional checks on their power are consistent with the model. Moreover, I argue that voters in Poland support PiS not because they have low commitments to the rule of law and democracy but because they genuinely believe that the incumbents’ intentions to reform the judiciary are sincere. Analysis of survey evidence from Poland illustrates that a high commitment to the rule of law is compatible with approval for PiS, particularly when combined with citizens’ beliefs that judicial reform is part of the delayed decommunization project and of Poland’s coming to terms with its past.

This article is organized as follows. The next section, drawing largely on literature in legal theory, explains the tension between the rule of law and TJ and shows how this tension played out in Poland to make it a possible candidate for authoritarian backsliding. Section 3 explains how the literature on the political economy of authoritarian backsliding might explain Poland’s democratic erosion. The focus here is on two categories of models: those in which citizens know their incumbent is exhibiting authoritarian tendencies and those in which they do not. The empirical section draws on original survey data from Poland to show that Poland’s backsliding trajectory is compatible with the NVC theory. The final sections present a shadow case from Hungary and conclude.

2 Lustration laggards, or operating within the constraints of rule of law

The principle of nulla poene sine lege (no punishment without a crime) questions whether those who committed human rights violations in the past in accordance with the law at the time ought to be held criminally responsible (Panebianco 2015; Graver 2016). It is largely on the grounds of violations of this principle that courts across post-communist Europe struck down TJ legislation passed by their legislatures in the 1990s (Poganyi 1997).

This was notoriously the case in Poland and Hungary, two examples of laggards in lustration and purges (Nalepa 2010). Moreover, among sectors potentially affected by personnel TJ, the judiciary in both these countries stands out as almost entirely lustration-free. This is corroborated by newly collected data from the Global Transitional Justice Dataset, presented in the figure below as a compilation of personnel TJ events in 6 post-communist countries since their transition to democracy circa 1990.

The graph shows the cumulative net personnel TJ events (lustrations and purges) pertaining to the judiciary from the date the country transitioned to democracy until 2013. “Net events” denotes positive TJ events net of negative events. Cumulative net events in year t are the sum of net events from the time of the transition until 2016 (last 3 years are omitted as there are no additional events between 2013 and 2016). Following Bates et al. (2020), I refer to a positive TJ event as the submission of a TJ proposal to the floor of the legislature, the passage of such legislation, the upholding of such legislation as constitutional by a supreme court, or the overturning of a presidential veto against such legislation. In the case of truth commissions, the publication of the commission’s report(s), and the extension of the commission’s mandate are also considered progressive TJ events. A negative event is the voting down of a bill, a presidential veto issued against a bill, a failure to overturn such a veto by the legislature, or the constitutional court striking a bill down. Bates, Cinar, and Nalepa use thus-defined events as building blocks for more refined measures. Because judiciary lustrations and purges are already a fairly disaggregated event, there are too few data points to use any of these more refined measures. Hence, in this paper I have elected to simply present all the data. The advantage of using this newly created dataset as opposed to previous databases, such as the Transitional Justice Research Collaborative, is its granular nature and the fact that it codes every event pertaining to advancing the transitional justice process forward (positive events) or backward (negative events). As a result, it allows me to pick up on threats of transitional justice implementation long before a mechanism is actually implemented. It also allows me to avoid long periods with no events, simply because there was no implementation. A final advantage of this dataset is that it extends to 2016 allowing me to capture a much longer time trend that the Transitional Justice Research Collaborative would (Fig. 1).

We see from the figure that Poland is among the countries with the lowest number of cumulative net events: only 5. Moreover, in contrast to Bulgaria and Romania, the other country cumulatively netting 5 events, it arrived at this number through a series of positive events (the passage of TJ by the legislature) followed in close succession by negative events (the reversals of these bills by the Constitutional Tribunal). Hungary, which has 7 net cumulative events, also has a number of such reversals (visibly in 2004).

The judiciary was scarcely lustrated before the populist Law and Justice (PiS) party came to power in 2015 because even after the parliament passed lustration bills, the country’s Constitutional Tribunal struck them down, citing the sharp conflict between these bills and the principle of judicial independence (Nalepa 2010; David 2003; Horne 2009; Magalhaes 1999). The Tribunal’s justification for these decisions was that, as a new democracy, Poland could not reconcile the principles of the rule of law and of non-retroactivity, in particular, with exposing judges for communist collaboration because such collaboration had been required by law under communism.Footnote 1 Likewise, in Hungary, the Constitutional Court shielded the judiciary and other elites from lustration and also barred the return of property expropriated by the communist party to its rightful owners (Sólyom et al. 2000; Sólyom 2003).

While Poland and Hungary’s courts’ formalist interpretation of the law stifled the progression of TJ, the liberal governments that ruled these countries through the 1990s and early 2000s also played a part in letting “bygones stay bygones.” These governments prioritized joining the European Community and NATO over launching full-scale TJ programs. Moreover, for fear of appearing to undermine the rule of law, they especially avoided extending TJ programs to the judiciary.Footnote 2 This move earned both Poland and Hungary praise from the international legal community. Yet, as this article argues, unsettled scores with the judiciary’s “ghosts of the past” have given the governments who succeeded the liberal cabinets—PiS in Poland and Fidesz in Hungary—a pretext for embarking on a series of judiciary reforms that undermine principles of the rule of law even more.

In 2018, crowds of protesters chanting “Constitution, constitution!” interrupted Polish President Duda’s speech during his visit to the Gdansk Shipyard, where the Solidarity trade union was born. Their protest alluded to the fact that Duda was failing at the job of enforcing the Basic Law. Duda remarked: “You are allowed to protest because I respect the constitution, but rest assured that a majority of people living on the Coast today feel threatened by the fact that there are justices on the Supreme Court who pronounced sentences on members of the opposition during Martial Law.” Jaroslaw Kaczynski has, on numerous occasions since his party became the dominant force in parliament, used the unfinished decommunization project as a pretext for weakening the judicial branch. Since 2015, PiS has accused the liberal wing of the Solidarity trade union (including Adam Michnik, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, and Jacek Kuron, among others), who had negotiated the transition during the roundtable talks, for striking a deal with the communists that promised amnesty of past wrongdoings in exchange for power-sharing. The accusations resonated with the public. Poland’s initial TJ project was extremely mild (Nalepa 2010). As mentioned above, lustration never reached the judiciary thanks to vetoes from the constitutional court. Unsurprisingly, when Kaczynski started replacing liberal judges on the Constitutional Tribunal (by sending them into early retirement) with PiS-sympathizers, he framed the move using the language of decommunization.Footnote 3 The next section explains why this framing was critical to the success of authoritarian backsliding in Poland.

3 Competing theories of authoritarian backsliding

In the last few years, many scholars have tackled the phenomenon of democratic erosion.Footnote 4 In a 2020 paper, Milan Svolik formalizes a scenario where elite polarization is so high that citizens prefer to elect an autocrat who is ideologically closer to them than a democratic politician who is ideologically further away (Svolik 2020). In Svolik’s model, elite polarization drives voters to knowingly elect an openly autocratic incumbent into office because the cost of being ruled by an ideologically distant challenger is too high. Authoritarian backsliding, according to this mechanism, however, is still puzzling when it occurs in countries that have shown deep commitments to democratic values; such countries include the new polities of post-communist Europe.

Building on Svolik’s model, NVC allow the voters to be uncertain about the identity of the incumbent. They argue that whether citizens reelect an incumbent (who may be a closet autocrat or an ideological conservative) depends on elite polarization, polarization in the electorate (the ideological distance between the representative citizen and the alternative candidate from the opposition), and the probability that the incumbent is in fact a closet authoritarian. The NVC model is developed in two periods and is characterized by two policy dimensions: an ideological dimension and an authoritarian dimension. The ideological dimension encompasses policies that fit onto a liberal-conservative continuum. The authoritarian dimension reflects citizens’ tolerance for authoritarian power grabs. NVC assume that preference for democracy always dominates the ideological dimension. This last feature situates the NVC model fittingly in the post-communist context, where democratizations a few decades ago revealed strong support for rule of law and a deep aversion to authoritarian power grabs. TJ polices map onto the left–right policy dimension well: preferences for harsh accountability go hand in hand with conservative ideology, and preferences for mild TJ characterize elites on the left.

In the first period, an incumbent politician—who may be an ideological conservative or a closet autocrat—only implements policy on the first, ideological dimension. This ideological dimension, in turn, limits the range of policies she will be able to implement in the second term, if reelected. If the incumbent is not reelected into office, governing authority is transferred to a liberal challenger who is, with certainty, a democrat. In the second term, the elected politician picks policy on the authoritarian dimension. NVC find that probability of reelection of a closeted-autocrat politician increases with both elite polarization and polarization in the electorate and also decreases with increased beliefs that the incumbent is a closet autocrat.

To adjudicate between the Svolik and NVC theories, three features of the Polish case need to be established. First, the actions of Kaczynski and his party, PiS, indeed lend themselves to the ambiguous interpretation suggested by NVC: in other words, they are consistent both with the actions of a closet autocrat and of an ideologically motivated incumbent. Second, in recent years, Poland has exhibited an increase in elite polarization and in polarization in the electorate; third, voters casting their ballots for PiS believe that they are reelecting an ideological incumbent rather than a closet autocrat.

The remainder of this article is devoted to empirically corroborating the theory summarized above. It will focus on showing that the lack of TJ in Poland, and especially the shielding of the judiciary from decommunization, created circumstances that, in line with the NVC model of backsliding, were ripe for the country’s descent into authoritarianism. To establish the first point, I present a brief analytical narrative from Poland; to establish the second, I rely on both historical and recent opinion surveys.

4 An analytic narrative from Poland

PiS came to power in 2015 when it succeeded the liberal government of Civic Platform (PO). PO had been led for almost two complete terms by Donald Tusk until, in 2014, he became President of the European Council; at this point, he was replaced by Ewa Kopacz. Several factors contributed to PO’s subsequent failure in the parliamentary elections of 2015. First, in the midst of the Syrian refugee crisis, Kopacz promised the EU that Poland would accept 12,000 refugees. In a country approaching 40 million, this seemed like a “drop in the bucket.” Yet, in the context of terrorist attacks in Europe, PiS managed to spin the commitment as a threat to national security. In the end, PO was forced to walk back its promise, causing irreparable damage to perceptions of its resolve at home and abroad.

A second defeat came with the presidential elections in the summer of 2015, which the incumbent, Bronislaw Komorowski of PO, had taken for granted. Only 5 years earlier, Komorowski had won the Presidency in a landslide against Kaczynski.Footnote 5 However, in 2015, instead of Kaczynski, PiS put up Andrzej Duda, a young conservative from the South of Poland (the PiS stronghold). Duda, a Warsaw outsider, was able to dissociate himself from the political mainstream and won the presidency. Following his victory, the popularity of PO took another turn for the worse.Footnote 6 While executive power in Poland is wielded by the Prime Minister, who is typically the leader of the party coming out victorious in parliamentary elections, the result was interpreted as evidence of the public’s loss of confidence in PO under Kopacz leadership.

The “straw that broke the camel’s back,” however, was the outcome of an eavesdropping operation carried out in a handful of restaurants neighboring the Sejm, the Polish parliament. Recordings made by serving staff of a series of private conversations revealed top PO politicians discussing sensitive issues pertaining to privatization, foreign affairs, and even national security. Following the publication of a year’s worth of transcripts from these conversations, the PO’s Ministry of Internal Affairs swiftly shut the operation down. An investigation of the operation revealed no links to any political parties, although notably, none of the embarrassing conversations involved PiS politicians. As a result of the three crises in rapid succession, PO’s support declined substantively.

Following 8 years on the opposition benches, PiS emerged victorious in the October 2015 parliamentary election. Even though it won only a minority of the vote, it took an absolute majority of seats in the legislature. The success allowed PiS to establish Poland’s first single-party majority cabinet since 1989. It began its rule by undertaking several changes that could be perceived as steering away from democratic norms. A prominent example echoing the scandal of wiretapped PO conversations was a national security bill permitting wiretapping and granting government access to phone records and electronic data. The legislation was promptly sent to the Constitutional Tribunal for evaluation, but the authors of the bill defended it, stating that its aim was to preempt criminal activity.

Instead of waiting for the Court to make a decision, PiS started tinkering with the Court. First, President Andrzej Duda refused to swear in three justices who had been elected by a PO-controlled parliament in the previous term to replace judges whose terms were running out. This move was appealed to the Constitutional Tribunal itself, which upheld the constitutionality of the election of the three justices. Next, the PiS Cabinet Chief of Staff refused to publish the Constitutional Tribunal’s verdict, hoping to invalidate it. However, after the Supreme Court ruled that the Constitutional Tribunal’s verdicts had full force of the law from the moment they are handed down, regardless of publication, the three justices joined the bench.

PiS continued to deny the new judges’ legitimacy and elected three candidates of its own. These judges (referred to as “extras”) also joined the bench. When the Constitutional Tribunal’s Chief Justice, Andrzej Rzeplinski, refused to appoint them to sit on panels, PiS decided to take further action against the Court and appointed Julia Przylebska, a PiS loyalist, to replace Justice Rzeplinski. This was a controversial choice for at least two reasons. First, Poland’s National Council of the Judiciary had evaluated and rejected Przylebska as lacking qualifications for a post in the Appellate Court—that is, a lower court than the Constitutional Tribunal. Moreover, she had begun her judicial career in communist Poland, making her exactly the kind of judge PiS had promised to get rid of. In the next step, PiS passed two bills that shortened the terms of the judges of the Constitutional Tribunal.

To allow for better understanding of the succession of judicial reforms that followed, a brief primer on the Polish court system is in order. The system of courts is complex and made up of four levels: the regional, district, appellate, and Supreme Courts. Lower level courts are surprisingly influential due to a peculiarity of the Polish constitution: Article 178 of the Basic Law allows lower-level courts to engage in interpreting the constitution when the Constitutional Tribunal is incapable of doing so. Consequently, Article 178 jeopardizes the plans of Polish closet autocrats. Even if a ruling party replaces key constitutional justices of the Constitutional Tribunal with its supporters, it can only count on their effectiveness in upholding unconstitutional legislation if it can also prevent judges in all courts entitled to act upon such legislation on the basis of Article 178 from doing so. In order to influence these lower court judges, PiS thus also had to control the Supreme Court, the court of appeal for lower-level decisions. With the Supreme Court on PiS’s side, any judge interpreting the constitution at odds with the ruling party would risk having its decision reversed by the PiS-controlled Supreme Court. Since frequent reversals undermine judicial careers, few lower-court judges take this risk.

The Supreme Court is not only the court of appeal for lower-level courts: the constitution also makes it responsible for determining the validity of all nationwide referenda, as well as elections to the Sejm and Senate. Hence, it is within the powers of the Supreme Court to rule an election invalid, should an incumbent lose. Another key Supreme Court task is reviewing reports by parties seeking reimbursement for electoral expenditures. Poland, in contrast to the United States, has a public electoral campaign financing system. Upon clearing a threshold of 3% of the national vote, parties seek reimbursements for campaign expenditures up to 4.04 PLN per vote from the state treasury. Yet, to be reimbursed, the applicant’s books must be deemed “in order” by Supreme Court judges. Denial of compensation to opposition parties by an autocrat-controlled Supreme Court can thus be interpreted as a “slow-bleed” strategy to bankrupt the opposition and eliminate electoral competition.

The lateral institution to the Supreme Court is the Constitutional Tribunal, the equivalent of the Supreme Court in the US and of constitutional courts in other countries except in that it only deals with the constitutionality of legislation passed in the Sejm and of legal norms applied in decisions of lower-level courts.

A final key body worthy of inclusion in this primer is the National Council of the Judiciary. This independent body makes recommendations on who should be appointed as a judge and initiates disciplinary action against members of the judiciary. Final disciplinary decisions are carried out by a special Ombudsman for Discipline.

The next set of judicial reforms, initiated in the beginning of 2016, eliminated the middle layers of the court system—the regional and appellate courts—and forced judges over 65 to retire unless they received an exemption from the Minister of Justice. Such permission would only be granted following vetting by a special commission. The reforms also made it easier for the government to impose disciplinary actions on all judges, bypassing the National Council of the Judiciary. This has been accomplished by giving parliament the authority to appoint members to the National Council of the Judiciary.Footnote 7

In July 2017, the PiS controlled parliament approved legislation to drastically change the composition and functioning of the Polish Supreme Court. The Justice Minister was handed discretion over who among the judges of the Supreme Court could remain in office and who was to be forced into retirement. Effectively, this reduced the number of judges from 87 to 31.Footnote 8 The prerequisites for holding a Supreme Court seat were lowered to a minimum of 12 years of experience in a regional court.

Since the Minister of Justice already also holds the position of Prosecutor General, the reforms have allowed the ruling majority to choose both the prosecutor and the judge in every single court case. The bill was not implemented immediately as the speed with which PiS guided it through the legislative agenda invited public outcry. After tens of thousands of Poles in over 100 cities protested the rapid and radical reform, Andrzej Duda—PiS’s President—vetoed the bill, ostensibly to protest the facts that he had not been consulted at the time of its preparation and that it transferred too much power into the hands of the Minister of Justice. Nevertheless, following some compromises which distributed control over the selection of judges between the Ministry of Justice and the Presidency, Duda conceded and the final set of judiciary reforms was passed in December 2017.

Experts concluded that this most recent bill alone potentially conflicted with at least two articles of the constitution (Articles 181 and 182), but the measure was not struck down because PiS sympathizers already occupied a majority of the Constitutional Tribunal bench. Hence, so far, none of PiS’s actions can be unequivocally considered unconstitutional. Yet, the attractiveness of such moves to closet autocrats is clear: one can think of several reasons why a closet autocrat would want to take control over Poland’s Supreme Court, the National Council of the judiciary, and lower level courts in this way.

First, the Supreme Court could invalidate elections lost by PiS. Second, by using the “slow-bleed” strategy described above, it could deny reimbursements to opposition parties. Third, the most influential opposition party to date—Civic Platform—could take a heavy blow if Donald Tusk, its former leader and current Council of Europe president, were put on trial before the State Tribunal. The State Tribunal is a special judiciary body for assessing the constitutional liability of persons holding the highest state rank. This process could result in criminal punishment and a loss of civil rights. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court serves, ex oficio, as the justice presiding over the State Tribunal. Tusk’s alleged crime is the murdering of Jaroslaw Kaczynski’s twin brother, Lech Kaczynski, who was Poland’s president until he perished in a plane crash over Smolensk, Russia. According to Jaroslaw Kaczynski, Tusk sabotaged the investigation into the catastrophe and allowed it to be declared an accident much sooner than it ought to have been. Finally, gaining steering control over the Supreme Court would allow Kaczynski to pardon a close ally and associate, Mariusz Kaminski. In a 2015 case, a regional court sentenced Kaminski, the former head of the Central Anticorruption Bureau, to 3 years in prison for abuses of power. In November of 2015, within days of assuming office, President Andrzej Duda pardoned him. However, the Supreme Court annulled the pardon in March 2017. Barring a reversal, Kaminski would go to prison.

Polish political events in recent years suggest that very conflicting interpretations of PiS’s actions exist alongside each other. For some, PiS is a party of ideological conservatives that promises to complete, once and for all, Poland’s TJ program. To others, it is a party of closet autocrats. Policies that some interpret as dismantling checks and balances and undermining the rule of law can also be interpreted as settling scores with the communist past. Poland’s case is not isolated. Similar events are playing out in Hungary and Turkey. While Turkey has had a weaker standing on democratic principles than Poland and Hungary, Erdogan’s attempts to change the regime from parliamentary to presidential can be interpreted as coup-proofing or as an attempt to concentrate power in the hands of a single politician (Cinar, forthcoming).

5 Survey evidence

The previous section established that conditions for the NVC model could obtain in Poland. However, I have yet to establish that this model is actually better at explaining Poland’s backsliding trajectory than Svolik’s theory, which—recall—does not rely on uncertainty about the incumbent’s true identity. In this section, I adjudicate between these two models further by developing two contrasting hypotheses about the determinants of voting for PiS. Both models predict that voting for PiS ought to increase with polarization. However, in addition to elite polarization, the NVC requires polarization in the electorate and a negative effect of beliefs that the policies implemented by PiS are those of a closet autocrat. Specifically, voting for PiS is more likely when respondents believe that judicial reforms are none other than the continuation of a TJ program that should have reached the judiciary. Relatedly, while both models underscore polarization as a leading cause for reelecting the autocrat, the latter model is compatible with voters exhibiting a strong aversion to authoritarian rule.

I will first present evidence in support of both models. These first data come from historical surveys and illustrate increasing levels of polarization between political elites in Poland in the twenty first century. This can be used to support either the Svolik or the NVC model. Following this, I provide evidence from a contemporary survey that allows for adjudication between the two theories by showing that respondents’ willingness to reelect closet authoritarians impersonating ideological conservatives decreases with their beliefs that the incumbent is indeed a closet autocrat.

5.1 Elite polarization in historical surveys

The measuring of elite polarization is possible thanks to reliable public opinion polls that have been conducted according to a uniform sampling technique between 2001 and 2011. The surveys come from the Center of Public Opinion Research, CBOS, a public opinion polling company with more than 35 years of experience in conducting surveys.Footnote 9 It fields regular surveys on stratified samples representative of Polish citizens between the ages of 18 and 75. It uses face-to-face interviews and has consistently included in its questionnaire the same battery of questions pertaining to political preferences and trust of political institutions. The question I use from the historical surveys is “Persons in public life—in their behavior, in what they say, and what they try to achieve—can arouse more or less trust. We will show you now a list of persons active in public life and ask you to what extent this person is trustworthy. − 5 means that you feel great distrust towards this person, 0 means you are indifferent and 5 means that you trust them completely. And of course, you can make use of any numbers between − 5 and 5 to express your trust towards this person. Please let us know if you do not know this person.”

In addition, based on current political events, CBOS supplements the regularly-asked questions with additional ones (I will make use of these surveys in the next section of this article). The period 2001–2011 coincides with the time when PiS and PO—the two largest parties in Poland—alternated in government and were led by the same two leaders. Both parties are descendants of Electoral Action Solidarity (AWS), the umbrella party organization uniting former anti-communist dissidents with roots in the independent Solidarity trade union.Footnote 10 Beginning in 2003, the main cleavage dividing Polish voters was no longer allegiance to the former communist autocrats or their opposition, but a more classical conservative-liberal cleavage (Carroll and Nalepa 2019). At that time, the two parties started separating ideologically.

To measure elite polarization, I use CBOS’s feeling thermometer question, described above, gauging respondents’ sympathy towards Kaczynski and Tusk, the leaders of PiS and PO, respectively. The formula describing the polarization measure is

TrustPO represents trust towards the leader of PO, Donald Tusk (and in 2017, Grzegorz Schetyna); TrustPiS is the trust towards the leader of PiS; n is the total number of respondents.Footnote 11 The absolute value is necessary because we are interested simply in the absolute distance between the two leaders as perceived by individual respondents. If the absolute value is not taken before distances are averaged, differences may cancel each other out. For instance, if one respondent expresses highest sympathy for Kaczynski and lowest sympathy for Tusk, while another respondent expresses highest sympathy for Tusk and lowest for Kaczynski, the mean of their differentials would be zero without the use of the absolute value. Yet, such preferences are consistent with the highest elite polarization possible as measured by these questions.

Measuring polarization as the mean differential between sympathy for each of the primary party leaders is a slight departure from the way polarization is measured in the American Politics context, where individual respondents are asked for their views on specific issues and the responses of Democrats and Republicans are compared (see Fiorina and Abrams 2008). In this context, the main question is the extent to which polarization is explained by partisan sorting. I depart from this because I want to pin down how distant political elites are from one another in the eyes of the public. This measure is closer to the concept of voters’ perceptions from both Svolik and NVC.

Figure 2, below, shows the Elite Polarization (marked as “diff_mean”) trend starting in 2001 with the 92nd survey conducted by CBOS and ends in 2011 with the 165th survey. The figure shows an increase in polarization around the 140th survey (in 2005). This is the year PiS won a plurality in the parliamentary elections for the first time (and entered into a cabinet coalition with two other parties: Samoobrona and the League for Polish Families). The increase continues until 2011, the year when PO took over the reins of government, a situation that persisted until 2015. Elite polarization in the contemporary survey discussed in the next section is 4.707 with a standard deviation of 3.21, indicating that current elite polarization surpasses its highest value from the 2001–2011 period.

This result suggests that one of the conditions for the NVC equilibrium is satisfied in the Polish case. However, this evidence is also consistent with other models of authoritarian backsliding, such as that of Svolik (2020). To find more direct support for NVS, we need to look beyond increases in elite polarization over time and establish conditions for obtaining the equilibrium in which voters reelect incumbents because they are uncertain whether they are dealing with an ideologue or with a closet autocrat.

5.2 Polarization in the electorate: contemporary surveys

For this further evidence, I turn to a contemporary CBOS survey from August 2017, the month directly following a presidential veto over the bills proposing the politicization of the National Council of the Judiciary and the Supreme Court. Recall that the Supreme Court is the highest court of appeal and for all practical purposes overlaps with the Supreme Court of the US except for in verifying the constitutionality of legislation. The National Council of the Judiciary, on the other hand, is the sole advisory body nominating candidates for judges and initiating disciplinary action against judges.

The survey I use here was conducted within days of intense and nationwide protests that prompted the President’s decision to veto two bills that would have brought the judiciary under complete political control.

Although observational data from surveys does not allow me to establish that uncertainty about the kind of incumbent voters are facing causes voters to support the incumbent, I show evidence that the association between uncertainty and incumbent voting increases with anti-authoritarian attitudes, exactly as the NVC model would lead us to expect.

In addition to predicting this effect of beliefs, the NVC model leads to expectations that respondents perceiving elite polarization to be higher and respondents who are further away from the opposition candidate are likely to vote for the incumbent, even when their anti-authoritarian predisposition is high. I quantify Subjectively Perceived Elite Polarization (SPEP) with a measure related to the one described in Eq. (1), but I do not average the measure across respondents. Hence:

As before, I take the absolute value of the differential between trust in PiS leader Kaczynski and in the current PO leader (who is Schetyna and no longer Tusk). The index i indicates that this polarization is measured at the level of each respondent. The index over time is dropped because I now only deal with one survey.

Finally, I need to measure polarization in the electorate—that is, the distance between the citizen and the opposition candidate. This is best captured with simply the citizen’s sympathy toward Schetyna, the PO leader:

Next, to measure citizens’ beliefs as to whether they are facing a closet autocrat or an ideological conservative, I use respondents’ expressed attitudes on the July 2017 protests; these protests in defense of the National Council of Judiciary and Supreme Court independence led the President to veto the two controversial bills. Since the protesters argued that both reforms violated the constitution, a respondent’s support for the protest can serve as an indicator of a belief that the incumbent is a closet authoritarian. This variable is labeled Support_Protestsi

Finally, in order to measure how much citizens care for the authoritarian dimension, I use the degree to which respondents agree with the following four questions gauging respondents’ sensitivity to authoritarianism. The four questions that measure the respondents’ sensitivity to the authoritarian dimension asked the respondent about the extent to which he or she agreed with the following four separate statements.

-

1.

“Democracy is superior to any other form of rule” (variable labeled Authoritarian Ii)

-

2.

“For people like me, it does not matter whether the regime is authoritarian or democratic” (variable labeled Indifferenti)

-

3.

“Sometimes Non-democratic rule is better than democratic rule” (variable labeled Authoritarian IIi)

-

4.

“Government by a strong leader is decidedly better than democratic rule” (variable labeled- Strong Leaderi)

Respondents could “agree strongly,” “agree somewhat,” “rather disagree,” or “strongly disagree” with the above statements. The answers to the first of the four questions were recoded to match the other three, so that that all four answers increase with pro-democratic values. Higher values of these variables represent stronger disagreement and therefore more pro-democratic values.

It is important to point out that these questions are not simply picking up on sympathy for the opposition. A correlation table in the Appendix shows that the association of these measures with Polarization in the Electorate is low.

In the results reported below, I use an interaction term between Support_Protests and Polarization in the Electorate to reflect the fact that voting for the incumbent in equilibrium of the NVC model requires both sufficiently high polarization of the electorate and sufficiently low beliefs that the incumbent is a closet autocrat. The dependent variable is a dummy, PiSvoteri, indicating that a respondent i answered “PiS” to the question “Were the elections to the Sejm to take place this Sunday, which party would you vote for?” I used the question “Would you vote in the parliamentary elections were they to take place this Sunday?” to filter out non-voters. Thus, the regressions are run only on voters and the sample is slightly smaller than the representative sample of Poles between 18 and 75.

Table 1 presents a regression of PiSvoteri on this set of independent variables obtained from the survey along with demographics such as age, gender, and education.

Because of the dichotomous nature of my dependent variable, I chose a nonlinear probability model—specifically, a logit in the following format:

“Demographics” includes gender, employment status, urbanization, education, and religiosity.Footnote 12

I expect the effect of Subjective Perception of Elite Polarization and Polarization in the Electorate to be positive and \(SPEP_{i} *{\text{PiS}}\_{\text{Protest}}_{i}\) to be negative (and more negative for higher values of Polarization in the Electorate).

Results of four models run using different operationalizations of anti-authoritarian attitudes are presented in Table 1 below.

The effects of Polarization in the Electorate and SPEP are significant and in the expected direction, increasing the probability of voting for PiS. The individual effect of beliefs that the incumbent is a closet autocrat is negative. What is of interest, however, is the combined effect of beliefs and Polarization in the Electorate on the probability of voting for PiS. We see that while one of the constituent terms is negative, the other is positive. The optimal way to visualize these effects is by graphing the average effect of beliefs for different levels of polarization.

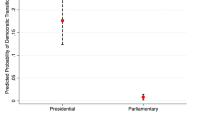

Figure 3 graphs the marginal effect of citizen beliefs that they are dealing with a closet autocrat (measured by PiSProtest) for different levels of Polarization in the Electorate (measured by TrustPO). It clearly shows that the interaction is negative. An increase in the belief that the voter is facing a closet autocrat decreases the probability of reelection for all levels of polarization in the electorate, but particularly for low levels of polarization. Concretely, when polarization is low, the average effect of the belief that the incumbent is a closet authoritarian is a decrease in the probability of reelection by about 52%, but when polarization is high, the effect is only about 20%.

Average marginal effects of belief that incumbent is a closet autocrat for different levels of polarization in the electorate (based on model 4 from Table 1)

The expectations for the effect of sensitivity to authoritarian rule (Authoritarian I, Authoritarian II, Indifferent and Strong Leader) is harder to interpret. Therefore, in order to illustrate the effect of this sensitivity, in the context of the survey at hand, I proceed as follows. First, I split the sample into respondents who answered the sensitivity questions positively (yes and rather yes → High) and those who answered the sensitivity questions negatively (no and rather no → Low). The results of these split sample tests are presented in Table 2 below.

In line with expectations, the effects of anti-authoritarian sensitivity (Antiauthoritarian2, Strong Leader, and Indifferent) are significant and in the expected direction in two out of three of the models representing citizens who are deeply anti-authoritarian, but entirely insignificant and/or in the wrong direction in all models representing citizens who weight the authoritarian dimension lightly. Furthermore, the substantive effects of these variables are higher than in the pooled sample from Table 1. In addition, that the remaining effects of the parameters remain stable in the models where respondents assign heavy authoritarian weight adds confidence to my findings.

6 Discussion and shadow case: Hungary

Although the above results corroborate the NVC as the appropriate model for understanding authoritarian backsliding in Poland, the inferences from a cross section of the population at one point in time should be interpreted with caution and should only be treated as a suggestive illustration of the dynamics at play in conjunction with the qualitative analytic narrative.

Moreover, at this point in time, Poland can be interpreted as, at worst, a “sliding” autocracy. A free media and a parliamentary opposition (since 2019 enjoying a majority in the upper house) remain, and Kaczynski has backed down in response to verdicts from the European Union Constitutional Court. Moreover, in July of 2020, the liberal candidate for the Presidency, Rafal Trzaskowski, came dangerously close in the general election tu replacing Duda, the current incumbent.

For a less ambiguous case, although one without similarly high-quality survey data, we may turn to Hungary. There, Fidesz, Victor Orban’s party, was elected into office with a majority large enough to change the constitution in 2010. Fidesz originated in the youth section of the Free Democrats’ Party (SzDSz), the most prominent dissident organization that negotiated the terms of democratic transition with the communists in 1989. When members of Fidesz became too old to call themselves a youth organization, they created a new party, changing the spelling of the organization from the acronym FiDeSz (which stood for “Youth Organization of SzDSz”) to Fidesz, which in Hungarian means “loyalty.” At the same time, the new party also began experimenting with conservative values. The final push toward abandoning liberal ideology was the competition for power between Fidesz and JOBBIK, a radical anti-Semitic and anti-Roma organization that was rapidly gaining traction in the polls, particularly in the peripheries of the country. To capture JOBBIK’s electorate, Fidesz moved even farther to the right.

Upon winning the 2010 elections, Orban blamed liberal policies and a failure to hold the communists accountable and for the rise of chauvinistic parties like JOBBIK. The first pieces of legislation that came out of the Fidesz-controlled legislature resulted in the weakening of the Constitutional Court. Within the post-communist region, the Hungarian Constitutional Court had more autonomy and authority than any other court,Footnote 13 enjoying powers of abstract review that allowed the court to issue decisions on the constitutionality of bills while they were still in the legislative process. The court could also review any bill after its passage, provided the bill had an impact on the country’s budget. Through these two channels, the Court had repeatedly struck down any but the mildest TJ laws.

Orban’s legislation first increased the number of judges on the bench so that he could staff it with his own supporters. Next, he did away with the prerogatives of abstract review and budget impact review. Finally, Fidesz severely restricted the rights of ordinary citizens to initiate the process of constitutional review. Even after passing ten amendments to the constitution, however, Fidesz was still not satisfied with the number of checks on its power that remained in place. Shortly, Orban started work on drafting an entirely new constitution. The pretext for changing the constitution was that the current Hungarian basic law had been negotiated during the roundtable talks with the communist government and had thus been agreed to under duress, as the communist regime was still in power. Given that these reforms could be interpreted as “doing transitional justice right,” many Fidesz supporters believed that Orban had remained “unchanged from the anti-communist rabble-rouser of the past and that charges of incipient dictatorship are left-wing fantasies” (NYT Nov 24, 2014). Five years ago, Zoltan Kovacs, his international spokesman, described him as “the same guy he used to be 25 years ago [who] wants to get rid of the attitudes, the remnants of the former system and get rid of the attitude that people live on social aid rather than work” (NYT Nov 24, 2014).

In April 2018, Orban’s Fidesz yet again emerged victorious in the parliamentary elections. This time, with only a plurality of the vote, the party cleared the two-thirds supermajority necessary to amend the constitution to bring the judiciary under the control of the executive. One did not have to wait long for the results. One month after the election, a flurry of judges from the National Judiciary Council started resigning just days before the announcement of a verdict against one of Orban’s oldest cronies (NYT, After Orban’s Victory, Hungary’s Judges Start to Tumble, May 1, 2018). The intimidation of a large number of judges who were part of the body meant to ensure judicial independence in Hungary became an ominous sign for the future of the rule of law in Hungary.

Orban’s authoritarian tendencies did not end with the judiciary. Since passing the new constitution, his government has brought all free print media to a close or transferred their operations online (Nolan 2019) and driven out of Hungary the Central European University, the bastion of liberal education founded by philanthropist and Open Society promoter George Soros.

Arguably, both Poland and Hungary match the conditions of the pooling equilibrium in which citizens reelect the incumbent not knowing whether he is a closet authoritarian. The above analytical narratives from Poland and Hungary show that these two countries are consistent with the ideological conservative and the closet autocrat pooling policy proposals and getting reelected into office.

7 Conclusion

In light of the evidence presented above, there are strong reasons to believe that TJ policies (or a lack thereof) are in part to blame for undermining the rule of law in places like Poland and Hungary. Because the judiciary was in large part shielded from purges and lustration, PiS and Fidesz, ruling parties on the right, have been able to convince the electorate that packing courts and bringing courts under political control are part of a decommunization program that would ultimately make the courts more efficient. I have argued that voters that reelected PiS did so not because they disapprove of the opposition so strongly that they were willing to replace the PO with an autocrat. Rather, the evidence presented here suggests that beliefs matter and that given the choice, PiS voters, too, want to avoid voting for someone they believe to be a closet autocrat. This argument is thus different from alternative models of authoritarian backsliding, such as Svolik’s, in which the ideological distance between the voter and the opposition incumbent is precisely what induces voters to cast their support for a candidate they know to be authoritarian.

Notes

See especially decisions K 39/97 and K 3/98 (Available at https://ipo.trybunal.gov.pl/ipo/Sprawa?cid=1&dokument=274&sprawa=3062.

And https://ipo.trybunal.gov.pl/ipo/Sprawa?cid=1&dokument=290&sprawa=3503).

See, for an alternative interpretation of keeping the former authoritarian judiciary intact, Popova (2012).

The Polish Constitutional Tribunal is the name for the country’s constitutional court, the body equipped with legislative oversight for compatibility with the Basic Law.

I use the terms democratic backsliding, authoritarian backsliding, and democratic erosion interchangeably here.

Komorowski ran as an incumbent even though he had never been elected into office. As a result of a tragic plane crash where Lech Kaczynski, President at the time and twin brother of Jaroslaw Kaczynski, perished, Komorowski, who at the time was House Speaker, had become president per the 1997 Constitution.

To be clear, Poland is a parliamentary regime with a directly elected president whose role is very symbolic. His only opportunity to affect policy is through vetoing legislation. The legislative veto, however, can be overturned with a three-fifths supermajority.

By a reading aligning with Brinks and Blais (2019), this move could be interpreted on the surface as broadening the coalition entitled to recall judges and thus as a move toward increasing and not decreasing the court’s autonomy. Yet, in the specific Polish context, where the overwhelming parliamentary majority is from PiS, the autonomy of the court was likely to decrease rather than increase.

Technically, 43 judges remained, but 12 would sit in a newly-created “disciplinary department,” so 31 judges would do the work of 87.

The Center for Public Opinion Research (CBOS) was created in communist Poland, but was given a fair amount of autonomy in running the surveys. CBOS was created when Poland’s communist authorities came to the realization that relying on reports from the secret police alone left them unprepared for outbreaks of popular dissidence. The Martial Law scenario could have been avoided altogether had the authorities been adequately informed of popular support for the Solidarity trade union. Relying exclusively on the reports from Sluzba Bezpieczenstwa (SB), the state secret police, was no longer feasible, because this data had informed the decision to legalize Solidarity (Kwiatkowski 2004). Among other strategies, the managerial positions of CBOS were staffed by sociologists from Warsaw University’s IFiS, the relatively independent social science department, whose team of sociologists, under the leadership of Stefan Nowak and Wojciech Adamski, started conducting public opinion poll surveys during the 18-month period when Solidarity was a legal trade union.

The breakup of AWS and the crisis of SLD have been considered by scholars studying the region to mark the end of the so-called “regime divide” in Poland (Grzymala-Busse 2001).

Theoretically, n should also have a t subscript, as it will vary from one survey to the next, although it is typically around 1000 respondents.

The demographics include whether the respondent lives in a large city or village (with towns being the default category) and whether the respondent is religious. Employment is measured with an ordinal scale between 0 and 1, with 0 and 1 representing unemployment and full-time employment, respectively. Religiosity is measured with a dummy variable which takes on the value of 1 when the respondent goes to church at least once a week or more on average. For Poland, a highly Catholic country made up of systematic churchgoers, setting the dummy at this threshold captures most variation.

I am using the terms “autonomy” and “authority” in line with the theory presented by Brinks and Blass (2019), who argue that these two dimensions better capture what conventionally passes as judiciary independence.

References

Bates, G., Cinar, I., & Nalepa, M. (2020). Accountability by numbers: A new global transitional justice dataset (1946–2016). Perspectives on Politics 18(1), 161–184.

Brinks, D., & Blass, A. (2019). DNA of constitutional justice in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carroll, R., & Nalepa, M. (2019). When do open lists matter? The consequences of the personal vote for party loyalty. Parliamentary Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsz027.

Cinar, I. (forthcoming). Democracy dismantled: Strategic choices of the would-be autocrats. Constitutional Political Economy.

David, R. (2003). Lustration laws in action: The motives and evaluation of lustration policy in the Czech Republic and Poland (1989–2001). Law & Social Inquiry, 28(2), 387–439.

Fiorina, M. P., & Abrams, S. J. (2008). Political polarization in the American public. Annual Review of Political Science, 11, 563–588.

Graver, H. P. (2016). Judges against justice. Berlin: Springer.

Grzymala-Busse, A. (2001). Coalition formation and the regime divide in new democracies: East Central Europe. Comparative Politics, 34(1), 85–104.

Horne, C. M. (2009). Late lustration programmes in Romania and Poland: Supporting or undermining democratic transitions? Democratization, 16(2), 344–376.

Huntington, S. P. (1993). The third wave: Democratization in the late twentieth century (Vol. 4). University of Oklahoma press.

Kaminski, M. M., Nalepa, M., & O’neill, B. (2006). Normative and strategic aspects of transitional justice. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 50(3), 295–302.

Kwiatkowski, S. (2004). Szkicownik z CBOS-u: Rysunki socjologiczne z tamtych lat. Wyższa Szkoła Społeczno-Gospodarcza.

Magalhaes, P. C. (1999). The politics of judicial reform in Eastern Europe. Comparative Politics, 32, 43–62.

Nalepa, M. (2010). Skeletons in the closet: Transitional justice in post-communist Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nolan, D. (2019). Remote controller: What happens when all major media, state and private, is controlled by Hungary’s government and all the front pages start looking the same. Index on Censorship, 48(1), 54–56.

Panebianco, G. (2015). The Nulla Poena Sine Culpa principle in European courts case law. In S. Ruggeri (Ed.), Human rights in European criminal law (pp. 47–78). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12042-3_4.

Pogany, I. S. (1997). Righting wrongs in Eastern Europe. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Popova, M. (2012). Politicized justice in emerging democracies: A study of courts in Russia and Ukraine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O’Donnell, G., & Schmitter, P. C. (2013). Transitions from authoritarian rule: Tentative conclusions about uncertain democracies. Johns Hopkins University Press

Snyder, J., & Vinjamuri, L. (2004). Trials and errors: Principle and pragmatism in strategies of international justice. International Security, 28(3), 5–44.

Sólyom, L. (2003). The role of constitutional courts in the transition to Democracy: With special reference to Hungary. International Sociology, 18(1), 133–161.

Sólyom, L., Brunner, G., & Breyer, S. G. (2000). Constitutional judiciary in a new democracy: The Hungarian Constitutional Court. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Svolik, M. W. (2020). When Polarization Trumps Civic Virtue: Partisan Conflict and the Subversion of Democracy by Incumbents. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 15(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1561/100.00018132.

Data source

CBOS surveys [insert all numbers here].

CBOS “Przeglądówka_Sierpien” survey, conducted on February 2, 2017 August, 18, 2017.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant No. 1658170), the Center for International Social Science Research at the University of Chicago and the Pozen Family Center for Human Rights at the University of Chicago.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nalepa, M. Transitional justice and authoritarian backsliding. Const Polit Econ 32, 278–300 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-020-09315-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-020-09315-5