Abstract

Mental health parity legislation can improve mental health outcomes. U.S. state legislators determine whether state parity laws are adopted, making it critical to assess factors affecting policy support. This study examines the prevalence and demographic correlates of legislators’ support for state parity laws for four mental illnesses— major depression disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), schizophrenia, and anorexia/bulimia. Using a 2017 cross-sectional survey of 475 U.S. legislators, we conducted bivariate analyses and multivariate logistic regression. Support for parity was highest for schizophrenia (57%), PTSD (55%), and major depression (53%) and lowest for anorexia/bulimia (40%). Support for parity was generally higher among females, more liberal legislators, legislators in the Northeast region of the country, and those who had previously sought treatment for mental illness. These findings highlight the importance of better disseminating evidence about anorexia/bulimia and can inform dissemination efforts about mental health parity laws to state legislators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mental illness is a significant contributor of morbidity and mortality in the United States, affecting more than 40 million adults each year (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2015). Public policies can have positive impacts on mental health either directly (e.g., implementing evidence-based mental health practices) or indirectly (e.g., improving healthcare infrastructure or addressing housing insecurity) (Purtle, Nelson, Bruns, et al., 2020; Purtle, Nelson, Counts, et al., 2020; Raghavan et al., 2008). Mental health parity laws seek to provide financial protection and improved insurance coverage (Beronio et al., 2014; Busch et al., 2013; Frank et al., 2014), as mental health services were historically associated with higher out-of-pocket costs and additional restrictions for service use and treatment (Goodell, 2014). Parity legislation is evidence-informed, having been reviewed and recommended by the US Community Preventive Services Task Force, and there is a continuum of coverage provided by parity laws. For example, some parity legislation may only extend to specific behavioral health conditions, while other laws may provide full, comprehensive coverage for all behavioral health conditions (Sipe et al., 2015).

Within the United States, mental health parity laws include both federal-level (e.g., the Mental Health Parity Act in 1996, the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act in 2008, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2010) and state-level legislation (e.g., comprehensive state behavioral health parity legislation (C-SBHPL)) (Community Preventive Services Task Force, 2012, 2015). While not uniformly applied across settings and populations, these policies have expanded mental healthcare coverage and reduced financial burden for millions of Americans (Beronio et al., 2014; Ettner et al., 2016).

There are several challenges to introducing, passing, and implementing parity legislation, such as C-SBHPL. First, legislators’ knowledge of a public health issue and use of research evidence impact policymaking (Bogenschneider et al., 2019). Unfortunately, there is often difficulty disseminating and communicating research findings to legislators, as well as limited research concerning how to increase the use of evidence among legislators and narrow the research-policy gap (Oliver et al., 2014; Purtle, Lê-Scherban et al., 2019; Purtle, Nelson, Bruns, et al., 2020; Purtle, Nelson, Counts, et al., 2020; Purtle, Brownson, et al., 2017; Purtle, Dodson, et al., 2018; Purtle, Goldstein, et al., 2017; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, et al., 2017; Votruba et al., 2020; Williamson et al., 2015). In the case of mental health parity laws, there are misconceptions about the financial impacts of these policies, with widespread concerns about higher insurance premiums due to the policies (Barry et al., 2010). The concerns deterred support for mental health parity laws and delayed progress until research containing updated cost projections was disseminated (Barry et al., 2006, 2010; Goldman et al., 2006).

Second, policy support can be impacted by factors like legislators’ demographics or personal beliefs; these effects have been documented both theoretically and empirically (Purtle et al., 2018; Purtle, Dodson, et al., 2018). For example, Corrigan and Watson included political ideology in their theoretical model describing mental health resource distribution (Corrigan & Watson, 2003). Previous studies have found associations between legislator characteristics (e.g., gender and race) and support for policies targeting tobacco (Cohen et al., 2002; de Guia et al., 2003; Goldstein et al., 1997), obesity (Welch et al., 2012), firearms (Payton et al., 2015), and mental health (Purtle et al., 2019a; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, et al., 2018). Research has also distinguished between legislator characteristics that can (e.g., beliefs about a policy) and cannot (e.g., political party affiliation) be changed and has examined their effect on support for comprehensive state behavioral health parity legislation (Purtle, Lê-Scherban, Wang, Brown, et al., 2019; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, Wang, Shattuck, et al., 2019). To complement the existing literature, there is a need for additional exploration of legislators’ characteristics, which can be used to better frame, tailor, and disseminate mental health policy-relevant information (Purtle, Brownson, et al., 2017; Purtle, Goldstein, et al., 2017; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, et al., 2017).

Lastly, stigma and personal experience with mental illness can further impact support for parity laws (McGinty et al., 2015, 2018; Pescosolido et al., 2010). Research has documented how gender (Corrigan & Watson, 2007), ethnicity (Corrigan & Watson, 2007; WonPat-Borja et al., 2012), education levels (Corrigan & Watson, 2007; Phelan & Link, 2004), and political ideology (DeLuca & Yanos, 2016; Vaccaro et al., 2018) are associated with the stigmatization of people with mental illness. Stigma can also vary based on the mental illness and accompanying diagnosis. For example, numerous studies have described the higher levels of stigmatization associated with mental illnesses such as schizophrenia or psychosis, compared to mental illnesses like major depression or substance use (Krendl & Freeman, 2019; McGinty et al., 2015; Pescosolido et al., 2010, 2013). However, experience with mental illness—either personally or through a close connection—has been associated with greater political and financial support of mental illness (McSween, 2002). With regard to legislators, perceptions of and experience with mental illness can impact both mental health resource allocation and policymaking, making them important factors to consider within policy research (Corrigan & Watson, 2003; Corrigan et al., 2004).

While previous studies have explored how legislator characteristics, such as knowledge (Bogenschneider et al., 2019), demographics (Cohen et al., 2002; de Guia et al., 2003; Goldstein et al., 1997; Payton et al., 2015; Purtle et al., 2019a; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, et al., 2018; Welch et al., 2012), and stigma (Nelson & Purtle, 2020; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, Wang, Brown, et al., 2019; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, Wang, Shattuck, et al., 2019) can impact policy support, to our knowledge, no study has examined predictors of variation for mental health parity coverage for different mental illnesses. To fill these gaps, this study compared support across four mental illnesses— major depression disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), schizophrenia, and anorexia/bulimia. This information may be used to better to tailor mental health research evidence for policymakers, which can impact their understanding of a policy issue and, consequently, their support.

Methods

Sample and Data Sources

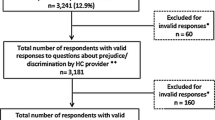

Data came from a survey of U.S. state legislators as part of a larger study designed to examine policymakers’ knowledge and attitudes regarding C-SBHPL and develop a conceptual framework to disseminate evidence to policymakers (Purtle, Brownson, et al., 2017; Purtle, Goldstein, et al., 2017; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, et al., 2017). Data were collected between March and September 2017 using a combination of postal mail, email, and telephone collection methods. The survey was designed using previous public opinion surveys as a guide; additional details about survey development and recruitment methods have been previously published (Purtle, Lê-Scherban, Wang, Shattuck, et al., 2019; Purtle, Brownson, et al., 2017; Purtle, Dodson, et al., 2018; Purtle, Goldstein, et al., 2017; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, et al., 2017). The full survey instrument is available in Appendix 1. The study was approved by the Drexel University Institutional Review Board (1608004754).

A random, state-stratified sample of 2902 legislators were contacted, with a total of 475 responses (response rate = 16.4%). This response rate was comparable to or higher than previous surveys of legislators (Anderson et al., 2016, 2020; Pagel et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2018). Previous analyses of this dataset found that respondents were more likely to be female (33% versus 23%, p < .001), Democrat (49% versus 42%, p = .001), and from the Midwest (31% versus 23%, p < .001), compared to nonrespondents (Purtle, Lê-Scherban, Wang, Brown, et al., 2019; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, et al., 2018). To account for these differences and increase our confidence that our results could be applied to the entire population of state legislators, we calculated and applied nonresponse weights for gender, political party, and geographic region using a sample post-stratification approach, an approach which has been used in previous analyses of this survey dataset (Nelson & Purtle, 2020; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, et al., 2018; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, Wang, Brown, et al., 2019; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, Wang, Shattuck, et al., 2019; Purtle, Dodson, et al., 2018).

Variables

Dependent variables were the extent to which legislators thought that health insurance companies should be required to provide coverage for four common mental illnesses (major depression disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, and anorexia/bulimia) that was equal to physical coverage. Legislators’ support or opposition was measured using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly oppose; 5 = strongly support). Due to the ordinal nature of the variables, these items were dichotomized as “strongly support” (yes, no). This was consistent with how the parity support variable was operationalized in the prior studies using this dataset (Nelson & Purtle, 2020; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, Wang, Brown, et al., 2019; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, Wang, Shattuck, et al., 2019; Purtle, Dodson, et al., 2018; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, et al., 2018).

Independent variables included eight legislator characteristics. Information regarding legislators’ gender (male, female) and political party (Republican, Democrat, other) were gathered via the National Conference of State Legislatures’ contact database. Legislators’ geographical region (Midwest, Northeast, South, West), education level (college or less, postgraduate degree), involvement on a health committee (yes, no), and years spent in office (≤ 5, 6 + years) were gathered via survey. Legislators’ political ideology was also included, a variable constructed in previous studies (Purtle et al., 2019a; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, et al., 2018). Political ideology encompassed legislators’ personal views on both social and fiscal issues using a 14-point scale (≤ 6 = liberal, 7–9 = moderate, 10–14 = conservative). Lastly, legislators’ experience with mental illness was assessed by asking whether they had ever personally sought treatment for a mental illness (yes, no).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample and the proportion of legislators that strongly supported parity for major depression, PTSD, schizophrenia, and anorexia/bulimia. Nonresponse weights were calculated, and a poststratification approach was used to adjust for differences between respondents and nonrespondents (Holt & Elliot, 1991). Bivariate analyses were conducted to compare strong support for each mental illness with legislator characteristics. Finally, we used multilevel (legislators within states) random-intercept binary logistic regression models to explore associations between legislator characteristics and support for parity for each mental illness. The multilevel models accounted for the clustering of support for parity for each mental illness among legislators in the same state (intraclass correlation coefficients = 0.10, depression; 0.05, PTSD; 0.08, schizophrenia; and 0.10, anorexia/bulimia). All analyses were performed with STATA 15.1.

Results

Within the sample, the majority of legislators were male (75%), Republican (54%), and had earned a college degree or less (51%) (Table 1). Respondents represented legislators from the Northeast (19%), South (32%), Midwest (24%), and West (25%), and 18% reported seeking treatment for a mental illness in the past. Most legislators reported strong support of parity for major depression (53%), PTSD (55%), and schizophrenia (57%). However, only 40% of respondents supported parity for anorexia/bulimia (Table 2).

Across each of the four mental illnesses, support for parity was highest among females (compared to males), Democrats (compared to Republicans or Others), those identifying as ideologically liberal (compared to moderate or conservative), and those who had sought treatment for a mental health issue (compared to those who had not). For example, 60% of female respondents strongly supported parity for anorexia/bulimia, compared to only 30% of males (p < .001) (Table 2). In the multivariate analyses, after adjusting for political party, geographical region, and personal experience with mental illness, a female legislator was 81% more likely than a male legislator to support parity for schizophrenia. Female legislators also had higher odds of supporting parity for anorexia/bulimia (AOR = 2.09; 95% CI 1.24, 3.53) (Table 3).

Among respondents, 80% of Democrats strongly supported parity for major depression, compared to 31% of Republicans (p < .001), with similar proportions for PTSD and schizophrenia (p < .001). Identifying as a Democrat was associated with higher odds of supporting parity for major depression (AOR = 2.76; 95% CI 1.29, 5.91) and PTSD (AOR = 2.43; 95% CI 1.21, 4.85) compared to Republicans or Others. Similarly, nearly 90% of ideologically liberal legislators supported parity for PTSD and schizophrenia, compared to only 30% of conservative legislators (p < .001). Compared to conservative respondents, liberal legislators also had significantly higher odds of supporting parity for major depression (AOR = 7.74; 95% CI 3.24, 18.51), PTSD (AOR = 8.69; 95% CI 3.68, 20.54), schizophrenia (AOR = 7.78; 95% CI 3.29, 18.40), and anorexia/bulimia (AOR = 8.86; 95% CI 3.83, 20.49), after adjusting for gender, political party, geographical region, and personal experience with mental illness. While the magnitude was smaller, ideologically moderate respondents had higher odds of supporting parity as well, compared to conservative legislators.

Lastly, there was an association between legislators’ geographical region and support for parity. For instance, 80% of legislators from the Northeast strongly supported parity for major depression, compared to 55%, 53%, and 37% from the West, Midwest, and South, respectively (p < .001). In multivariate analyses, legislators from the Northeast had significantly higher odds of supporting parity for depression (AOR = 6.27; 95% CI 2.28, 17.30), PTSD (AOR = 2.92; 95% CI 1.24, 6.88), schizophrenia (AOR = 2.94; 95% CI 1.18, 7.34) and anorexia/bulimia (AOR = 4.42; 95% CI 1.70, 11.47), compared to legislators from the South. In the regression models, personal experience with a mental illness was not a statistically significant predictor of support for parity, after adjusting for gender, political party, geographical region, and political ideology.

Discussion

This study explored the relationship between legislator characteristics and varriaiton in support for mental health parity laws for major depression, PTSD, schizophrenia, and anorexia/bulimia. Building on the existing literature surrounding perceptions of mental illness and support for mental health parity laws, legislators’ support for parity was highest for schizophrenia (57%) and PTSD (55%), followed by major depression (53%) and anorexia/bulimia (40%). Support for parity was generally higher among females, more liberal legislators, legislators in the Northeast region of the country, and those who had previously sought treatment for mental illness.

After multivariate adjustment, several legislator characteristics were predictors of support for parity, and the associated characteristics varied by mental illness. For example, gender was a significant predictor of support for parity for both schizophrenia and anorexia/bulimia, with female legislators being more supportive than males. Political party was a predictor of support for major depression and PTSD, with Democrats being more likely to support parity than Republican legislators. Compared to legislators in the South, those in the Northeast region were statistically more likely to support parity for each of the four mental illnesses. Ideology was the strongest predictor of support for major depression, PTSD, schizophrenia, and anorexia/bulimia, with liberal legislators more frequently supporting parity. Whether a legislator had previously sought treatment for a mental illness was not a significant predictor in the regression models.

These study findings are generally consistent with previous work involving policymakers’ support for public health legislation (Nelson & Purtle, 2020; Purtle, Goldstein, et al., Purtle, Goldstein, et al., 2017; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, Wang, Brown, et al., 2019; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, et al., 2018). Research has highlighted associations between public health policy support and legislator characteristics, such as gender, political party affiliation, and geographic location. For example, a 2017 study by Purtle and colleagues examined voting records of U.S. Senators in relation to public health policy recommendations and found that Democratic legislators and female legislators were more likely to support public health policies (Purtle, Goldstein, et al., Purtle, Goldstein, et al., 2017). They also reported that Southern Senators voted in support of public health policies less often than Senators from other regions of the country (Purtle, Goldstein, et al., Purtle, Goldstein, et al., 2017). Legislator characteristics, such as female gender and liberal political ideology have also been linked to greater levels of support for comphrehensive state behavioral health parity legislation and opioid use disorder parity legislation. Lastly, while personal experience with a mental illness has been linked to greater support of government spending (McSween, 2002) and legislation (Barry et al., 2010) for mental health, this was not a significant predictor of support for parity for any of the included mental illnesses in this study.

These study findings have two main implications. First, if certain legislator characteristics may impact support for mental health policies, these findings could be used to tailor future research evidence when disseminating to policymakers. For example, only one-third of male legislators strongly supported parity for anorexia/bulimia. Previous research has explored the effects of gender on perceptions of eating disorders, finding that men have lower levels of awareness of disease prevalence and severity than women (Shingleton et al., 2015). Compared to women, men are also more likely to minimize eating disorders and attribute these illnesses to personal weakness (Griffiths et al., 2014; Mond & Arrighi, 2012; Wingfield et al., 2011). As a result, information about the prevalence, causes, and impacts of eating disorders might be targeted and disseminated to male legislators. This issue is timely, as the COVID-19 era has resulted in a greater prevalence of eating disorders, higher rates of hospitalization, and worsening symptoms for both adults and adolescents, perhaps due to the changes in access to food, physical activity, social interaction, and healthcare facilities for many (Miniati et al., 2021; Otto et al., 2021; Toulany et al., 2022). Support for mental health parity was also significantly lower among ideologically conservative legislators across each of the four mental illnesses. For these legislators, data supporting the cost-effectiveness of parity laws or communications strategies to address mental health stigma could be disseminated (McGinty et al., 2018). Tailoring research to legislators based on their characteristics could increase legislators understanding of mental health issues, as well as their overall support of mental health policies.

Second, legislators’ levels of a support may relate to a perceived or relative “worthiness” of certain mental illnesses for inclusion in legislation, such as mental health parity laws (Conley, 2021; Corrigan & Watson, 2003). For example, across the four mental illnesses, support for parity was lowest for anorexia/bulimia, compared to depression, PTSD, and schizophrenia. Legislators’ support for parity may be impacted by several complex, interconnected factors, such as perceptions of personal responsibility for the illness, the potential threat to others, or the overall severity of a mental illness. For example, previous research has suggested that certain mental illnesses may be more socially undesirable than others (e.g., schizophrenia is less desirable than anxiety) (Krendl & Freeman, 2019). Similarly, some mental illnesses are perceived to be more controllable than others, thus attributing some degree of personal responsibility for the illness to the individual (e.g., depression is something that you can control, while schizophrenia is not) (Krendl & Freeman, 2019). Finally, certain mental illnesses are associated with greater levels of concern for violence or dangerousness (e.g., perceived greater risk of violence from someone with schizophrenia than from someone with depression) (Corrigan & Watson, 2007; Link et al., 1999). These perceptions may influence legislators’ support of mental health parity laws. For example, if legislators perceive that a mental illness, such as schizophrenia or PTSD, is severe, uncontrollable, and poses a threat of violence to others, legislators may be more inclined to support parity laws for that illness. Conversely, if a mental illness—like anorexia/bulimia—is believed to be less harmful or a result of personal choice (Griffiths et al., 2014; Mond & Arrighi, 2012; Wingfield et al., 2011), legislators may be less supportive of mental health parity. These findings underscore the importance and potential benefits of implementing comprehensive parity laws, which would ensure coverage for mental illnesses, which might otherwise be deemed “unworthy.”

Limitations

The results of this study should be viewed in light of several limitations. First, data were generated from a survey of legislators, with a response rate of 16%. Though this response rate is higher than or comparable to other surveys of legislators (Anderson et al., 2016, 2020; Niederdeppe et al., 2016; Pagel et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2018), the sample accounts for 6.4% of all state legislators in the United States, and it is possible that response bias is present. Additionally, survey responses may have been impacted by social desirability bias on some items (e.g., Have you personally ever sought treatment for a mental health issue?). Third, the survey items inquired about insurance parity for only four specific mental illnesses, and also combined anorexia and bulimia, despite being diagnostically distinct. We did not ask about a greater number of mental illnesses given the length limitations of the survey, which covered a wide range of issues related to C-SBHPL. Our findings might not be generalizable to other mental illnesses. Our study suggests potential value in future research that assesses opinions about a wider range of mental illnesses.

Future Directions

Despite the federal and state mandates for parity, evidence suggests that we have yet to achieve true parity between mental and physical health (Davenport et al., 2019; Walsh et al., 2022). For example, policy ambiguity and/or a lack of policy knowledge have resulted in instances of additional treatment limitations imposed by insurance companies (Gabella, 2021). These violations to parity laws can encompass both quantifiable standards (e.g., dollar limits, number of visits permitted) and more subjective limitations on the scope of mental health services (e.g., requiring prior authorization, first-fail policies) (Berry et al., 2017; Manatt, 2019). These issues are further compounded by inconsistent monitoring and enforcement of mental health parity legislation at both the state and federal levels (Berry et al., 2017). Ultimately, the treatment limitations and lack of enforcement have resulted in additional barriers to accessing mental health services (Appelbaum & Parks, 2020). These challenges, coupled with the varying levels of mental health parity law support discussed in this study, provide ample opportunities for future research.

First, more information is needed regarding ways to increase support for mental health policies—particularly those targeting eating disorders, which had considerably less support for mental health parity in this sample. Similarly, a greater focus is needed on decreasing mental health stigma on a broader scale, as this may increase legislators’ support for mental health policies. However, though numerous small-scale interventions have reported short-term decreases in stigma surrounding mental illness, larger campaigns’ efforts have often ranged from little-to-no effect to actually increasing stigma toward individuals with mental illness (Malla et al., 2015; Stuart, 2016; Thornicroft et al., 2016). Future efforts to address stigma should be multi-faceted and multilevel to impact the complex indiviudal-, social-, and structural-level forces (Stuart, 2016). Additionally, future research could benefit from a better understanding of strategies to disseminate research evidence to policymakers, including how communication strategies impact support for mental health policies in audiences less inclined to support parity legislation (e.g., conservative legislators). This may involve developing or testing communication strategies for both policymakers and the general public (e.g., utilizing narratives of people with mental illness (McGinty et al., 2018) or emphasizing the cost-effectiveness of a policy (Purtle et al., 2019a; Purtle, Lê-Scherban, et al., 2018). Researchers could also examine the effects of additional legislator characteristics (e.g., race/ethnicity) on policy support, as this additional information may be beneficial for policy advocates and researchers disseminating policy-relevant information. Lastly, though researchers have examined patterns of policy support in relation to legislators’ characteristics, additional research would be beneficial to explore why these characterstics impact policy support and how to best frame, tailor, and disseminate mental health policy-relevant information accordingly.

References

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2015). Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH Series H-50, Issue. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.htm

Anderson, S. E., Butler, D. M., & Harbridge, L. (2016). Legislative institutions as a source of party leaders’ influence. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 41(3), 605–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/lsq.12124

Anderson, S. E., DeLeo, R. A., & Taylor, K. (2020). Policy entrepreneurs, legislators, and agenda setting: information and influence. Policy Studies Journal, 48(3), 587–611. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12331

Appelbaum, P. S., & Parks, J. (2020). Holding insurers accountable for parity in coverage of mental health treatment. Psychiatric Services, 71(2), 202–204. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900513

Barry, C. L., Frank, R. G., & McGuire, T. G. (2006). The costs of mental health parity: Still an impediment? Health Affairs, 25(3), 623–634. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.623

Barry, C. L., Huskamp, H. A., & Goldman, H. H. (2010). A political history of federal mental health and addiction insurance parity. The Milbank Quarterly, 88(3), 404–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00605.x

Beronio, K., Glied, S., & Frank, R. (2014). How the affordable care act and mental health parity and addiction equity act greatly expand coverage of behavioral health care. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 41(4), 410–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-014-9412-0

Berry, K. N., Huskamp, H. A., Goldman, H. H., Rutkow, L., & Barry, C. L. (2017). Litigation provides clues to ongoing challenges in implementing insurance parity. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 42(6), 1065–1098. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-4193630

Bogenschneider, K., Day, E., & Parrott, E. (2019). Revisiting theory on research use: Turning to policymakers for fresh insights. American Psychologist, 74(7), 778–793. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000460

Busch, A. B., Yoon, F., Barry, C. L., Azzone, V., Normand, S. L., Goldman, H. H., & Huskamp, H. A. (2013). The effects of mental health parity on spending and utilization for bipolar, major depression, and adjustment disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(2), 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030392

Cohen, J. E., de Guia, N. A., Ashley, M. J., Ferrence, R., Northrup, D. A., & Studlar, D. T. (2002). Predictors of Canadian legislators’ support for tobacco control policies. Social Science & Medicine, 55(6), 1069–1076. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00244-1

Community Preventive Services Task Force. (2012). Improving mental health and addressing mental illness: Mental health benefits legislation. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/mental-health-mental-health-benefits-legislation

Community Preventive Services Task Force. (2015). Recommendation for mental health benefits legislation. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 48(6), 767–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.018

Conley, D. L. (2021). The impact of structural stigma and other factors on state mental health legislative outcomes during the Trump administration. Stigma and Health, 6(4), 476–486. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000331

Corrigan, P. W., & Watson, A. C. (2003). Factors that explain how policy makers distribute resources to mental health services. Psychiatric Services, 54(4), 501–507. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.54.4.501

Corrigan, P. W., & Watson, A. C. (2007). The stigma of psychiatric disorders and the gender, ethnicity, and education of the perceiver. Community Mental Health Journal, 43(5), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-007-9084-9

Corrigan, P. W., Watson, A. C., Warpinkski, A. C., & Gracia, G. (2004). Stigmatizing attitudes about mental illness and allocation of resources to mental health services. Community Mental Health Journal, 40(4), 297–307. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:COMH.0000035226.19939.76

Davenport, S., Gray, T. J., & Melek, S. P. (2019). Addiction and mental health vs. physical health: Widening disparities in network use and provider reimbursement. https://www.milliman.com/en/insight/addiction-and-mental-health-vs-physical-health-widening-disparities-in-network-use-and-p

de Guia, N. A., Cohen, J. E., Ashley, M. J., Ferrence, R., Rehm, J., Studlar, D. T., & Northrup, D. (2003). Dimensions underlying legislator support for tobacco control policies. Tobacco Control, 12(2), 133. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.12.2.133

DeLuca, J. S., & Yanos, P. T. (2016). Managing the terror of a dangerous world: Political attitudes as predictors of mental health stigma. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 62(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764015589131

Ettner, S. L., Harwood, J. M., Thalmayer, A., Ong, M. K., Xu, H., Bresolin, M. J., Wells, K. B., Tseng, C.-H., & Azocar, F. (2016). The mental health parity and Addiction Equity Act evaluation study: Impact on specialty behavioral health utilization and expenditures among “carve-out” enrollees. Journal of Health Economics, 50, 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2016.09.009

Frank, R. G., Beronio, K., & Glied, S. A. (2014). Behavioral health parity and the Affordable Care Act. Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation, 13(1–2), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/1536710X.2013.870512

Gabella, J. (2021). Mental health care disparity: The highs and lows of parity legislation. Health Matrix: Journal of Law-Medicine, 31, 377–408.

Goldman, H. H., Frank, R. G., Burnam, M. A., Huskamp, H. A., Ridgely, M. S., Normand, S. L., Young, A. S., Barry, C. L., Azzone, V., Busch, A. B., Azrin, S. T., Moran, G., Lichtenstein, C., & Blasinsky, M. (2006). Behavioral health insurance parity for federal employees. New England Journal of Medicine, 354(13), 1378–1386. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa053737

Goldstein, A. O., Cohen, J. E., Flynn, B. S., Gottlieb, N. H., Solomon, L. J., Dana, G. S., Bauman, K. E., & Munger, M. C. (1997). State legislators’ attitudes and voting intentions toward tobacco control legislation. American Journal of Public Health, 87(7), 1197–1200. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.87.7.1197

Goodell, S. (2014). Health Policy Brief: Mental Health Parity.

Griffiths, S., Mond, J. M., Murray, S. B., & Touyz, S. (2014). Young peoples’ stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs about anorexia nervosa and muscle dysmorphia. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(2), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22220

Holt, D., & Elliot, D. (1991). Methods of weighting for unit non-response. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series D (The Statistician), 40(3), 333–342. https://doi.org/10.2307/2348286

Krendl, A. C., & Freeman, J. B. (2019). Are mental illnesses stigmatized for the same reasons? Identifying the stigma-related beliefs underlying common mental illnesses. Journal of Mental Health, 28(3), 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1385734

Link, B. G., Phelan, J. C., Bresnahan, M., Stueve, A., & Pescosolido, B. A. (1999). Public conceptions of mental illness: Labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. American Journal of Public Health, 89(9), 1328–1333. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.89.9.1328

Malla, A., Joober, R., & Garcia, A. (2015). “Mental illness is like any other medical illness”: A critical examination of the statement and its impact on patient care and society. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience: JPN, 40(3), 147–150. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.150099

Manatt, Phelps, & Phillips LLP. (2019). Understanding mental health parity: Insurer compliance and recent litigation. https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/understanding-mental-health-parity-46147/

McGinty, E. E., Goldman, H. H., Pescosolido, B., & Barry, C. L. (2015). Portraying mental illness and drug addiction as treatable health conditions: Effects of a randomized experiment on stigma and discrimination. Social Science & Medicine, 1982(126), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.010

McGinty, E., Pescosolido, B., Kennedy-Hendricks, A., & Barry, C. L. (2018). Communication strategies to counter stigma and improve mental illness and substance use disorder policy. Psychiatric Services (washington, D. C.), 69(2), 136–146. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700076

McSween, J. L. (2002). The role of group interest, identity, and stigma in determining mental health policy preferences. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 27(5), 773–800. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-27-5-773

Miniati, M., Marzetti, F., Palagini, L., Marazziti, D., Orrù, G., Conversano, C., & Gemignani, A. (2021). Eating disorders spectrum during the COVID pandemic: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.663376

Mond, J. M., & Arrighi, A. (2012). Perceived acceptability of anorexia and bulimia in women with and without eating disorder symptoms. Australian Journal of Psychology, 64(2), 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9536.2011.00033.x

Nelson, K. L., & Purtle, J. (2020). Factors associated with state legislators’ support for opioid use disorder parity laws. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 82, 102792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102792

Niederdeppe, J., Roh, S., & Dreisbach, C. (2016). How narrative focus and a statistical map shape health policy support among state legislators. Health Communication, 31(2), 242–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2014.998913

Oliver, K., Innvar, S., Lorenc, T., Woodman, J., & Thomas, J. (2014). A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-2

Otto, A. K., Jary, J. M., Sturza, J., Miller, C. A., Prohaska, N., Bravender, T., & Van Huysse, J. (2021). Medical admissions among adolescents with eating disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-052201

Pagel, C., Bates, D. W., Goldmann, D., & Koller, C. F. (2017). A way forward for bipartisan health reform? Democrat and republican state legislator priorities for the goals of health policy. American Journal of Public Health, 107(10), 1601–1603. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304023

Payton, E., Thompson, A., Price, J. H., Sheu, J. J., & Dake, J. A. (2015). African American legislators’ perceptions of firearm violence prevention legislation. Journal of Community Health, 40(3), 439–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-014-9954-3

Pescosolido, B. A., Martin, J. K., Long, J. S., Medina, T. R., Phelan, J. C., & Link, B. G. (2010). ‘A disease like any other’? A decade of change in public reactions to schizophrenia, depression, and alcohol dependence. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(11), 1321–1330. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09121743

Pescosolido, B. A., Medina, T. R., Martin, J. K., & Long, J. S. (2013). The “Backbone” of stigma: Identifying the global core of public prejudice associated with mental illness. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 853–860. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301147

Phelan, J. C., & Link, B. G. (2004). Fear of people with mental illnesses: The role of personal and impersonal contact and exposure to threat or harm. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 45(1), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650404500105

Purtle, J., Brownson, R. C., & Proctor, E. K. (2017). Infusing science into politics and policy: The importance of legislators as an audience in mental health policy dissemination research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 44(2), 160–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0752-3

Purtle, J., Dodson, E. A., Nelson, K. L., Meisel, Z., & Brownson, R. (2018). Legislators’ sources of behavioral health research and preferences for dissemination: Variations by political party. Psychiatric Services (washington, D. C.), 69(10), 1105–1108. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800153

Purtle, J., Goldstein, N. D., Edson, E., & Hand, A. (2017). Who votes for public health? U.S. senator characteristics associated with voting in concordance with public health policy recommendations (1998–2013). SSM—Population Health, 3, 136–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.12.011

Purtle, J., Lê-Scherban, F., Shattuck, P., Proctor, E. K., & Brownson, R. C. (2017). An audience research study to disseminate evidence about comprehensive state mental health parity legislation to US State policymakers: Protocol. Implementation Science, 12(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0613-9

Purtle, J., Lê-Scherban, F., Wang, X., Brown, E., & Chilton, M. (2019a). State legislators’ opinions about adverse childhood experiences as risk factors for adult behavioral health conditions. Psychiatric Services (washington, D. C.), 70(10), 894–900. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900175

Purtle, J., Lê-Scherban, F., Wang, X., Shattuck, P. T., Proctor, E. K., & Brownson, R. C. (2018). Audience segmentation to disseminate behavioral health evidence to legislators: An empirical clustering analysis. Implementation Science, 13(1), 121. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0816-8

Purtle, J., Lê-Scherban, F., Wang, X., Shattuck, P. T., Proctor, E., & Brownson, R. (2019b). State legislators’ support for behavioral health parity laws: The influence of mutable and fixed factors at multiple levels. The Milbank Quarterly, 97(4), 1200–1232. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12431

Purtle, J., Nelson, K. L., Bruns, E. J., & Hoagwood, K. E. (2020a). Dissemination strategies to accelerate the policy impact of children’s mental health services research. Psychiatric Services (washington, D. C.), 71(11), 1170–1178. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900527

Purtle, J., Nelson, K. L., Counts, N. Z., & Yudell, M. (2020b). Population-based approaches to mental health: History, strategies, and evidence. Annual Review of Public Health, 41, 201–221. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094247

Raghavan, R., Bright, C. L., & Shadoin, A. L. (2008). Toward a policy ecology of implementation of evidence-based practices in public mental health settings. Implementation Science, 3, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-3-26

Shingleton, R. M., Thompson-Brenner, H., Thompson, D. R., Pratt, E. M., & Franko, D. L. (2015). Gender differences in clinical trials of binge eating disorder: An analysis of aggregated data. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(2), 382–386. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038849

Sipe, T. A., Finnie, R. K. C., Knopf, J. A., Qu, S., Reynolds, J. A., Thota, A. B., Hahn, R. A., Goetzel, R. Z., Hennessy, K. D., McKnight-Eily, L. R., Chapman, D. P., Anderson, C. W., Azrin, S., Abraido-Lanza, A. F., Gelenberg, A. J., Vernon-Smiley, M. E., Nease, D. E., Jr., Community Preventive Services Task, F. (2015). Effects of mental health benefits legislation: A community guide systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 48(6), 755–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.022

Stuart, H. (2016). Reducing the stigma of mental illness. Global Mental Health (cambridge, England), 3, e17–e17. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2016.11

Thornicroft, G., Mehta, N., Clement, S., Evans-Lacko, S., Doherty, M., Rose, D., Koschorke, M., Shidhaye, R., O’Reilly, C., & Henderson, C. (2016). Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. Lancet, 387(10023), 1123–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00298-6

Toulany, A., Kurdyak, P., Guttmann, A., Stukel, T. A., Fu, L., Strauss, R., Fiksenbaum, L., & Saunders, N. R. (2022). Acute care visits for eating disorders among children and adolescents after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(1), 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.09.025

Vaccaro, J., Seda, J., DeLuca, J. S., & Yanos, P. T. (2018). Political attitudes as predictors of the multiple dimensions of mental health stigma. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 64(5), 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764018776335

Votruba, N., Grant, J., & Thornicroft, G. (2020). The EVITA framework for evidence-based mental health policy agenda setting in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy and Planning, 35(4), 424–439. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czz179

Walsh, M. J., Becerra, X., & Yellen, J. L. (2022). Realizing parity, reducing stigma, and raising awareness: increasing access to mental health and substance use disorder coverage (2022 MHPAEA Report to Congress Issue. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/EBSA/laws-and-regulations/laws/mental-health-parity/report-to-congress-2022-realizing-parity-reducing-stigma-and-raising-awareness.pdf

Welch, P. J., Dake, J. A., Price, J. H., Thompson, A. J., & Ubokudom, S. E. (2012). State legislators’ support for evidence-based obesity reduction policies. Preventive Medicine, 55(5), 427–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.09.008

Williamson, A., Makkar, S. R., McGrath, C., & Redman, S. (2015). How can the use of evidence in mental health policy be increased? A systematic review. Psychiatric Services (washington, DC), 66(8), 783–797. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400329

Wingfield, N., Kelly, N., Serdar, K., Shivy, V. A., & Mazzeo, S. E. (2011). College students’ perceptions of individuals with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44(4), 369–375. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20824

WonPat-Borja, A., Yang, L., Link, B., & Phelan, J. (2012). Eugenics, genetics, and mental illness stigma in Chinese Americans. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(1), 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0319-7

Zhu, J. M., Chhabra, M., & Grande, D. (2018). Concise research report: The future of medicaid: State legislator views on policy waivers. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(7), 999–1001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4432-8

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant Nos. R21MH111806, K01MH113806, R21MH125261, P50MH11366), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Grant No. P30DK092950), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Grant No. K24AI134413), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Grant No. U48DP006395), and the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital. The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the National Institutes of Health or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was performed by JP, and data analysis was performed by MP. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MP, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pilar, M., Purtle, J., Powell, B.J. et al. An Examination of Factors Affecting State Legislators’ Support for Parity Laws for Different Mental Illnesses. Community Ment Health J 59, 122–131 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-022-00991-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-022-00991-1