Abstract

Translocation is an increasingly common component of species conservation efforts. However, translocated populations often suffer from loss of genetic diversity and increased inbreeding, and thus may require active management to establish gene flow across isolated populations. Assisted gene flow can be laborious and costly, so recipient and source populations should be carefully chosen to maximise genetic diversity outcomes. The greater stick-nest rat (GSNR, Leporillus conditor), a threatened Australian rodent, has been the focus of a translocation program since 1985, resulting in five extant translocated populations (St Peter Island, Reevesby Island, Arid Recovery, Salutation Island and Mt Gibson), all derived from a remnant wild population on the East and West Franklin Islands. We evaluated the genetic diversity in all extant GSNR populations using a large single nucleotide polymorphism dataset with the explicit purpose of informing future translocation planning. Our results show varying levels of genetic divergence, inbreeding and loss of genetic diversity in all translocated populations relative to the remnant source on the Franklin Islands. All translocated populations would benefit from supplementation to increase genetic diversity, but two—Salutation Island and Mt Gibson—are of highest priority. We recommend a targeted admixture approach, in which animals for supplementation are sourced from populations that have low relatedness to the recipient population. Subject to assessment of contemporary genetic diversity, St Peter Island and Arid Recovery are the most appropriate source populations for genetic supplementation. Our study demonstrates an effective use of genetic surveys for data-driven management of threatened species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Conservation and recovery actions for threatened animal species increasingly involve the establishment of translocated populations (Weeks et al. 2011). Such populations can increase a species’ total population size and geographic range, and thereby guard against extinction (Frankham et al. 2017). However, founder events, population isolation and small population sizes can increase inbreeding and loss of genetic diversity within these populations (Frankham et al. 2010). These processes can lead to inbreeding depression and reduced adaptive capacity, both of which increase the long-term risk of population extirpation and species extinction (Crnokrak and Roff 1999; Frankham et al. 1999). Genetic diversity can be preserved in translocated populations by using a large number of unrelated founders and encouraging rapid population growth after initial release (Tracy et al. 2011).

Establishing gene flow between isolated populations through supplementation (also termed ‘reinforcement’) can also improve or maintain the genetic diversity of small populations (Margan et al. 1998). This has been demonstrated in species such as the alpine ibex (Capra ibex; Biebach and Keller 2012), boodie (Bettongia lesueur; Thavornkanlapachai et al. 2019), mountain pygmy possum (Burramys parvus; Weeks et al. 2017), Florida panther (Puma concolor coryi; Pimm et al. 2006) and Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii, McLennan et al. 2020). However, assisted gene flow through translocations can be laborious and costly to sustain (Frankham et al. 2017). To support decisions by conservation practitioners, genetic monitoring can be used to assess whether supplementation is warranted (Schwartz, et al. 2007).

The greater stick-nest rat (GSNR, Leporillus conditor), an Australian murid, has been the subject of an ongoing translocation program since 1985 (Copley 1999a, b; Moseby et al. 2011). GSNR populations were drastically reduced following the introduction of European herbivores and predators, leading to their extinction on the Australian mainland in the 1930’s (Copley 1999a). The species survived on two linked offshore islands that remained free of introduced mammals – West and East Franklin Islands in South Australia. In 1996, the species was classified as ‘Endangered’ under the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (Woinarski and Burbidge 2016). The captive breeding and translocation program subsequently increased the total population size and geographic range of the GSNR, with four translocated populations considered successful (Short et al. 2019). This has led to the GSNR’s IUCN conservation status being downgraded twice: from ‘Endangered’ to ‘Vulnerable’ in 2008, and from ‘Vulnerable’ to ‘Near Threatened’ in 2016 (Woinarski and Burbidge 2016).

Despite these achievements, the genetic diversity represented within the translocated populations remains unknown. Small (< 1000 individuals) and isolated populations are expected to experience loss of genetic diversity and increased inbreeding, especially in combination with serial founder events. A genetic study of the GSNR population at one translocation site, Arid Recovery in South Australia, found that diversity and inbreeding did not differ greatly from that population’s founding individuals, which were released 17 years earlier (White et al. 2018). However, the genetic diversity of GSNR at Arid Recovery and at the other translocated populations has never been compared to the original source population on the Franklin Islands, which is a necessary step to document the true extent of genetic change (Biebach and Keller 2009).

Currently, supplementation is being considered as a means of increasing the species’ long-term sustainability. However, it remains unclear which populations to prioritise for supplementation. In our study, we undertook genetic monitoring of seven populations (one remnant, one captive, one establishing, and four translocated) of GSNR in order to inform conservation management. We used a large single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) dataset generated using double-digest, restriction-site associated sequencing (ddRAD-seq; Poland et al. 2012) to understand genetic structure, diversity and inbreeding in the original remnant wild population and to document genetic changes since translocation across populations. Diversity loss and inbreeding in translocated GSNR populations is likely to vary as a result of differing founder numbers, number of serial founder events, time since translocation, and changes in population size since translocation (Table 1; Frankham et al. 2017; Short et al. 2019).

We use our results to make recommendations about which GSNR populations should be considered priorities for supplementation and which represent the best sources for assisted gene flow. Thus, our results have important management implications. To assist conservation practitioners who may not have a genetics background to navigate our research, we have provided a glossary (Supplementary Materials, SM Table 1) of the main measures that were estimated from our data, including definitions and interpretations.

Materials and methods

The life- and translocation history of greater stick-nest rats

As their name implies, GSNR build insulating nests of sticks, which protect them against predation and extreme weather (Robinson 1975; Copley 1999a). Nests have been observed to be occupied over several generations and are added to or modified on a regular basis (Copley 1999a). However, whether or how kinship affects co-habitation amongst adults is not well-understood, with the number of rats per nest usually low (i.e. often restricted to a single female, up to three young and occasional visiting males; (unpublished observations; Moseby and Bice, 2004). Individuals have an adult body mass of 180–450 g, and their maximum observed lifespan is > 8 years in captivity and > 5 years in the wild (Procter 2007). Males reach sexual maturity at ~ 240 days and females at ~ 180 days, with females producing litters of typically 1–2 young up to three times a year (Procter 2007), although there is some evidence that they are seasonal breeders in the wild (Short et al. 2019). Generation length, defined as the average age of parents of the current cohort, is approximately 2 years (Pacifici et al. 2013; Woinarski and Burbidge 2016).

The GSNR became extinct on the Australian mainland in the 1930’s, presumably due to severe habitat degradation from introduced herbivores, exacerbated by predation by introduced cats (Felis catus) and, later, foxes (Vulpes vulpes; Copley 1999a). Today, the only remnant extant population of GSNR is on the East and West Franklin Islands in the Nuyts Archipelago, South Australia (Robinson 1975). These islands are linked at most low tides by a 400 m sand bar (Copley 1999a).

The GSNR conservation program began in 1985 when two individuals were transferred from the Franklin Islands to a breeding facility at what is now Monarto Zoological Park, South Australia (Copley 1988). Between 1985 and 1994, a total of 29 rats were transferred to this breeding colony (Copley, 1999b; Short et al. 2019). A break-down of the sex-ratio and proportion of animals from each island transferred to the captive colony by year is given in SM Table 2. Animals were sourced from both islands and breeding was managed using a studbook in order to guide mate selection and avoid inbreeding (Copley 1994). The progeny from Monarto were subsequently used as a source for several translocations to cat and fox-free islands and mainland sites (comprehensively detailed in Short et al. 2019) before the captive breeding program ceased in 2004.

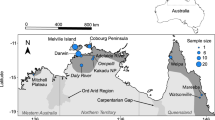

Sites of successful GSNR translocations (Fig. 1) include Reevesby Island in the lower Spencer Gulf of South Australia (Pedler and Copley 1993); Salutation Island in Shark Bay, Western Australia (Copley 1999b; Morris 2000); St Peter Island in Nuyts Archipelago, South Australia (Copley 1999b); and Arid Recovery (founded from Reevesby Island and Monarto individuals) at Roxby Downs, on mainland South Australia (Moseby and Bice, 2004; Moseby and Read 2006; Moseby et al. 2011). Additionally, and most recently, translocation into a second mainland population—at Mt Gibson Wildlife Sanctuary in south-central Western Australia—commenced, initially using individuals from West Franklin Island (Page et al. 2011). This establishing population was supplemented by individuals from the Alice Springs Desert Park captive colony in 2015 and from St Peter Island in 2018 (Short et al. 2019).

Modified from Figure 1 in Copley (1999a). Red stars represent the only remaining remnant population of the GSNR on the Franklin Islands and the red circles represent translocation sites. The Monarto captive breeding colony is shown as a white circle, as it was discontinued in 2004

Estimated former distribution (orange shading) and current sites (red circles and stars) of the greater stick-nest rat (GSNR).

The number of founders to these sites (prior to sampling for this study) varied from 40 to 153 individuals, the sex ratio of founders was close to 50:50 at all sites, and time between founding and sampling for our study varied from 5 to 26 years (Table 1; Short et al. 2019). All translocated populations were subject to serial founder events. That is, the founders of these sites were sourced from populations that were themselves a captive colony or translocation site, and so on. The number of serial founder events per population varied from 2 to 5 (Table 1). Population sizes at each of these sites have been monitored intermittently using a combination of one or more methods including live trapping, track counts, camera trapping, spot lighting and incidental records (Short et al. 2019). We provide estimates of population sizes at time of sampling for each site in Table 1, but note that these numbers contain considerable uncertainty (Short et al. 2019).

Sample collection

We obtained genetic samples from all six extant populations of the GSNR (East and West Franklin Island, Reevesby Island, St Peter Island, Salutation Island, Arid Recovery and Mt Gibson) and from the former captive colony at Monarto Zoological Park. Tissue samples were obtained from museum frozen tissue collections, during routine monitoring programs, or during targeted trapping, as described below. Although our sample sizes for some populations are small (Table 2, minimum N = 6 for Monarto and Mt Gibson), we believe our high-resolution SNP dataset has compensated for this and has enabled accurate inference (Nazareno et al. 2017). We conducted down-sampling experiments to test this assumption (see below).

Samples from animals on the Franklin Islands were taken during monitoring conducted in 1994. Samples from Reevesby Island and the Monarto captive colony were collected during trapping for the translocation to Arid Recovery in 1998–1999, and thus represent the founders for the Arid Recovery population. These previously-collected samples were stored frozen at the Australian Biological Tissue Collection (ABTC, South Australian Museum) and sub-sampled for our study. Animals from all other populations were trapped in 2016 using Elliott traps or Sheffield cage traps baited with peanut butter and rolled oats, or fresh fruit/vegetables. Ear or tail tissue samples were taken using a sterile ear punch, small sharp scissors or scalpel blade and stored in individual vials of ethanol. Ethics approval was obtained for all trapping conducted as part of this study (SM Table 3). At all sites where possible, effort was made to avoid sampling close relatives that may co-reside in the same nest. This was done by trapping across widely-spaced grids, or at widely-distributed nest sites. Samples from Arid Recovery, Reevesby Island and Monarto were collected and sequenced as part of a previous study by White et al. (2018).

DNA extraction and ddRAD-seq library preparation

DNA extraction was performed using a salting out method (Rivero et al. 2006). Extracts were then used to generate ddRAD-seq libraries following the protocol of Poland et al. (2012), with some modifications. Detailed methodologies for DNA extraction and library preparation are provided (SM methods). Prior to sequencing, libraries were quantified using Tapestation 2200 (Agilent) and pooled at equi-molar concentrations. Pooled libraries were sequenced in 1 × 75 bp (single-end) high output reactions on the Illumina Next-seq at the Australian Genome Research Facility, Adelaide, Australia.

Sequence processing

We used STACKS v1.35 (Catchen et al. 2011, 2013) to process the ddRAD-seq data and call SNPs (also referred to below as ‘loci’, a more general term for genetic markers), employing parameters recommended by Mastretta-Yanes et al. (2015) to minimise errors and to maximise SNP recovery. Samples with fewer than 500,000 reads were excluded from downstream analysis. After initial processing and SNP calling (see SM methods), we filtered loci with heterozygosity > 0.7 (to remove potential paralogs), with more than 25% missing data and with minor allele frequencies of < 0.05 using the program PLINK v1.9 (Purcell et al. 2007). We chose not to filter sites based on deviations from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium as our dataset is ill-suited to such a filter due to a large expected Wahlund effect (Wahlund 1928) across populations and expected inbreeding within them. We do not believe this has affected downstream analyses as our filtering in the STACKS pipeline and quality checking procedures (described below) should have identified most genotyping errors, and we additionally filtered for putatively non-neutral sites using an FST-outlier test (also below).

We identified and removed close relatives from the dataset (Wang 2018) by estimating pairwise genetic relatedness (genetic R) between individuals within each population separately. We merged the Franklin Islands into one population for this analysis as relatives may occur across those islands. We used the Hedrick and Lacy method (Hedrick and Lacy 2015) implemented in the program ngsRelate (Korneliussen and Moltke 2015). This method is the most appropriate for identifying relatives in our dataset as it compensates for inbreeding and bounds genetic R to between zero and one. We identified pairs of individuals with genetic R > 0.2 as 1st or 2nd degree relatives and removed one individual from each pair (in instances where an individual occurred in multiple pairs, we selectively removed this individual to minimise sample reduction).

Finally, we tested for loci under putative selection using the Bayesian FST-outlier method implemented in BayeScan v2.01 using the default settings (Foll and Gaggiotti 2008). A threshold value to detect selection was set using a conservative maximum false discovery rate (the expected proportion of false positives) of 0.01. Loci found to be putatively under selection were removed from the dataset before downstream analyses as we are interested here in making inferences about neutral evolutionary processes, and loci under selection may significantly bias results (Helyar et al. 2011).

Quality control

Raw sequences from blank control samples were also run through the STACKS pipeline, matching the output to the previously-constructed consensus catalogue. Our aim was to remove any potentially erroneous loci that were also present in the library blank samples. However, upon inspection, none of the loci found in the blank controls were present in the final datasets, having been removed by the filtering steps.

To allow the estimation of error rates, ten samples—representing individuals from four of the eight populations—were sequenced twice from independent DNA aliquots in separate libraries. To control for sequencing depth, replicate reads were subsampled to 1 million, 750,000, and 500,000 reads. All sub-sampled replicates were run through the STACKS pipeline as above. Allelic error rate was then estimated by counting mismatching alleles at loci for which both replicates had been sequenced.

Population structure across the Franklin Islands

Although the Franklin Islands are connected daily at low-tide by a sand-bar, it is unclear how much gene flow occurs between the two sites. As the source of all GSNR translocations, the designation of the Franklin Islands as one or two populations has implications for future translocations and for our downstream analyses. Thus, we first aimed to determine whether the Franklin Islands should be considered as one or two populations using two clustering methods. First, we ran STRUCTURE (Pritchard et al. 2000), a program that clusters samples by optimizing Hardy-Weinberg expectations within groups, using the admixture model with the number of clusters (K) ranging from 1 to 5. For each K, three runs consisting of 150,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) steps were performed, with the first 50,000 steps discarded as burn-in. To assess the most likely K, we calculated the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and mean likelihood (LK) using the R (R Core Team 2019) package starmie (Tonkin-Hill and Lee 2016). Secondly, we used discriminant analysis of principal components (DAPC), as implemented in the R-package adegenet (Jombart 2008) which, unlike STRUCTURE, does not rely on pre-defined genetic models. We used the adegenet function find.clusters to run successive DAPC analyses for K = 1–5 and calculated the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for each model.

Tests for admixture in the Mt Gibson population

The Mt Gibson GSNR population was founded using individuals from multiple sources across a number of years (Table 1) and our sampling occurred in July 2016, after the introduction of individuals from a second source. Given the ages and trapping history of the sampled individuals, three of the six Mt Gibson individuals included in our study are potential Mt Gibson/Alice Springs F1 hybrids. To test this, we ran STRUCTURE and DAPC, as above, on all Mt Gibson and Arid Recovery (the immediate source of the Alice Springs Desert Park colony; Table 1) individuals.

Genetic diversity and inbreeding

For each population, we calculated observed and (unbiased) expected heterozygosity (HO, HE), and allelic richness corrected for sample size (AR) using the R package hierfstat (Goudet 2005). We calculated the individual inbreeding statistic (F), which is equivalent to FIT when averaged over individuals (i.e. homozygosity excess relative to expectations given the allele frequencies of the whole sample), using the program PLINK v1.9 (Purcell et al. 2007). We tested for significant differences in these statistics between the captive/translocated populations and the Franklin Islands population (both as a single population and treating the two islands separately) using a Wilcoxon rank sum tests, corrected for multiple testing in R. For each population we also tested whether expected and observed heterozygosity were significantly different using a Wilcoxon rank sum test, again correcting for multiple tests.

Our sample sizes per population are variable (range 6–64), so we attempted to quantify the accuracy of our statistics when sample size is small. We followed a similar procedure to Pruett and Winker (2008) and down-sampled the Reevesby Island population-sample (the only population-sample large enough to enable sufficient down-sampling) to different sample sizes 100 times each and re-calculated our summary statistics for each dataset. To examine accuracy (how close the estimator is to the ‘true’ value, i.e. when N = 64), we calculated the scaled root mean square error (SRMSE) for each sample size and statistic (Walther and Moore 2005).

Genetic relatedness and population differentiation

Using the R package ‘Related’ (Pew et al. 2015) and the method described by Wang (2002), we re-calculated genetic R for the entire dataset and averaged these estimates for pairs within the same populations and across populations to examine relative genetic similarity. We used this measure because genetic R of two individuals is an estimate of the hypothetical inbreeding coefficient of their offspring. Thus, genetic R averaged across all pairs of individuals from the same or different populations gives an estimate of the gain in diversity (as measured by heterozygosity) when crossing two randomly chosen individuals from each population.

We used Wang’s estimator here as, unlike the Hedrick and Lacy (2015) method used above to identify close relatives, it does not force genetic R to between zero and one. Genetic R is a measure of genetic similarity between two individuals, relative to the allele frequencies in a reference sample (Hardy 2003). Since our reference in this case was our total sample, we expected some pairs of individuals to have genetic R less than zero (i.e. individuals from different populations) and thus restricting genetic R to above zero would have artificially inflated our averages (Wang 2017). Due to our choice of reference sample, genetic R in this case does not correspond to expected pedigree values, but rather, relative genetic similarity.

We tested for significant differences in within-population genetic R between captive/translocated populations and the Franklin Islands (both as a single population and separately) using Wilcoxon rank sum tests, corrected for multiple testing in R.

Genetic distance between populations was measured as using pairwise FST (Weir and Cockerham 1984), with bootstrapping used to calculate confidence intervals using the R package hierfstat (Goudet 2005).

Effective population size

We used the program NeEstimator (Do et al. 2014) to estimate effective population size (Ne) using two different methods: the LDNe method (based on the pattern of linkage disequilibrium between loci [Waples and Do 2008]), and the two-sample temporal method (based on changes in allele frequency over a known number of generations; [Waples 1989]). Confidence intervals were jointly estimated in NeEstimator using the jackknife approach (Jones et al. 2016). As for the inbreeding and diversity statistics, we first used down-samples from Reevesby Island to assess the accuracy of both estimators when sample size is small.

The temporal method estimates the harmonic mean Ne for the time between the two temporal samples. For this method, we used the estimator of F as proposed by Jorde and Ryman (2007). It is important to note that estimates of Ne derived using the temporal method are dependent on the generation time used. We have used the generation length for GSNR published by the IUCN (2 years, Woinarski and Burbidge 2016) as calculated from reproductive lifespan, age at sexual maturity and gestation length (Pacifici et al. 2013). However, for the GSNR these characteristics are mostly estimated from captive populations and may not be representative of wild populations. An increase or decrease in generation time would inversely affect our Ne estimates.

For the Monarto, Reevesby Island, Salutation Island and St Peter Island populations, we used the Franklin Islands (combined) as the first sample, assuming that our 1994 samples from the Franklin Islands were a good proxy for the founders of each of these populations. The number of generations between time points for these populations is equal to the number of generations between the last year translocation occurred and sampling (Table 1). For Mt Gibson, we used the West Franklin individuals alone as the initial time point, as individuals from East Franklin were not used to found Mt Gibson, with the number of generations between time points also equalling the number of generations between translocation and sampling (Table 1). For Arid Recovery, we ran two separate runs of NeEstimator. The first used the combined Monarto and Reevesby Island samples (the immediate source populations of Arid Recovery) as the initial time point, with the number of generations between samples calculated as number of generations between translocation and sampling. The second run used the combined Franklin Island population as the initial time point. In this case, the number of generations was calculated as the sum of the number of generations between translocation and sampling at Reevesby Island, and the number of generations between translocation and sampling at Arid Recovery (Table 1).

Finally, we used the estimated Ne for each population to estimate the rate of genetic diversity loss (as measured by HE) in succeeding generations after sampling as 1/2Ne (Frankham et al. 2010; Wright 1969).

Results

Sequencing

A total of 146 GSNR individuals from seven sites were successfully sequenced (SM Table 5). Samples had an average of 4,323,612 reads that passed quality filtering. After processing and filtering, a dataset of 8,723 SNPs was generated, with an average of 9.86% missing data per individual (SM Table 5). We identified 26 pairs of close relatives in the sample set; eight among Arid Recovery individuals, 11 among Reevesby Island individuals, three among Salutation Island individuals and four among Mt Gibson individuals (SM Fig. 1). No closely related pairs were detected for St Peter Island, Franklin Islands or the Monarto captive colony. We removed 18 individuals (eight from Reevesby Island, five from Arid Recovery, two from Mt Gibson and three from Salutation Island) from the dataset to eliminate these closely related pairs (SM Table 5). BayeScan identified 44 loci under putative selection (SM Fig. 2). These were removed before proceeding with downstream analyses.

The estimated average allelic error rate, calculated between pairs of replicates sub-sampled to varying depths, did not differ with sequencing depth (SM Table 6, mean = 0.025), indicating that our cut-off of 500,000 reads per sample was appropriate.

Population structure across the Franklin Islands

Our STRUCTURE analysis of the Franklin Island individuals suggested that the two island populations are genetically distinct, with two being the most likely number of clusters (K = 2 had the lowest BIC and highest LK, SM Fig. 3). However, the difference in the likelihood between K = 1 and K = 2 was low and our DAPC analysis found no support for K > 1 (BIC was lowest for K = 1; SM Fig. 3). Additionally, when we examined the cluster assignment results for K = 2 from both STRUCTURE and DAPC, we found that although all West Franklin individuals were assigned to one cluster, a single East Franklin individual also grouped with them (SM Fig. 4). We continued to group this individual as an East Franklin Island individual, under the assumption that it was a recent migrant but note that it may also represent a case of mislabelling during collection or laboratory work. Given the ambiguous support for structuring between the two islands, we present results obtained when treating the islands both together and separately.

Tests for admixture in the Mt Gibson population

We found no evidence of admixed ancestry in the sampled Mt Gibson animals. Both STRUCTURE and DAPC found that the optimal K for the combined Arid Recovery and Mt Gibson samples respectively was two (lowest BIC and highest LK; SM Fig. 5). While DAPC perfectly split the two populations between the two clusters, STRUCTURE identified three Mt Gibson individuals with small amounts of Arid Recovery ancestry (SM Fig. 6). However, two of these individuals can be excluded as hybrids as they were first captured and marked before translocation from Alice Springs Desert Park occurred, and, for all three of these individuals, the amount of admixture fell well below the expected 50% for F1 hybrids (SM Fig. 6).

Genetic diversity and inbreeding

Our down-sampling results showed that, as expected, the accuracy of inbreeding and diversity summary statistics decreased with sample size, but that this difference was small (maximum SMRSE = 0.511, SM Table 7, SM Fig. 7). This is in agreement with a larger simulation study (Nazerano et al.. 2018), which showed that, when the number of loci are greater than ~ 1000, genetic diversity measures are little impacted by sample size down to N ~ 8.

Diversity and inbreeding summary statistics varied among populations (Table 2; Fig. 2). The Franklin Islands had significantly higher diversity (as measured by HE, HO and AR, Table 2) than all other populations, except for comparisons of HO to Mt Gibson and Reevesby Island. Individual inbreeding (F) of the Salutation Island population was significantly higher than the Franklin Islands, but all other comparisons of F were non-significant (Fig. 2). In all populations other than Mt Gibson, HO was significantly lower than HE.

Mt Gibson is unusual in these statistics. Despite having HO and average individual inbreeding (F) that were similar to the Franklin Islands (Fig. 2), Mt Gibson had very low HE and AR, and was also the only population in which HO was significantly higher than HE, indicating a heterozygosity excess relative to expectations (Table 2).

Violin- and box-plots representing individual inbreeding coefficients (F) per population of greater stick-nest rats. Higher values of F indicate an individual is more inbred. Black outside lines represent data density, grey horizontal lines represent the median, and the grey boxes are bound by the 25th and 75th quartile. Populations with significantly higher average inbreeding (across individuals) than the Franklin Islands considered as a single population, or either the East or West Franklin Island populations considered separately, are denoted with linking lines and asterisks

Genetic relatedness and population differentiation

All captive/translocated populations have significantly higher within-population genetic R than do the Franklin Islands, except for comparisons of Reevesby Island to East Franklin Island, and Monarto to both the Franklin Islands (combined) and to East and West Franklin Island separately (Fig. 3). The highest average within-population genetic R was in Mt Gibson (mean = 0.31, standard deviation = 0.14), and the lowest in the Franklin Islands (mean = − 0.11, standard deviation = 0.07). Average between-population genetic R (Table 3; standard deviations given in SM Table 8) was below zero for all cross-population comparisons. It was highest between East Franklin Island and Monarto (− 0.064) and lowest between Salutation and East Franklin Islands (− 0.24).

Violin- and box-plots representing individual pairwise genetic relatedness per population of greater stick-nest rats. Black outside lines represent data density, grey horizontal lines represent the median, and the grey boxes are bound by the 25th and 75th quartile. Higher values of genetic R represent greater relatedness. Significant differences are not shown as all captive/translocated populations were significantly different from the Franklin Islands, except for comparisons of Reevesby Island to East Franklin, and Monarto to both the Franklin Islands combined and East and West Franklin Islands separately

Pairwise FST was low overall (Table 3) and was highest between Mt Gibson and Salutation Island (0.193), and lowest between East Franklin Island and Monarto (0.006). All pairwise FST measures were significant as none of the 95% confidence intervals overlapped zero (SM Table 9).

Effective population size

Down-sampling results showed that, while Ne estimation using the temporal method was reasonably robust to low sample size (all SRMSE < 1), the LD method was not (max SRMSE = 34.38, SM Table 7, SM Fig. 8). Thus, we only present results using the temporal method (Table 4). Estimates for Monarto returned an infinite result, likely due to small sample size in combination with limited time between the two sampling points (2.5 generations). For the other translocated populations, we found that estimates of Ne ranged from 6.3 (Mt Gibson) to 46.9 (St Peter Island). The two estimates of Ne for the Arid Recovery population using different initial time points gave similar point estimates with overlapping 95% confidence intervals (Table 4). The expected effect of the estimated effective population sizes on HE over succeeding generations (since sampling) is provided (Fig. 4; Table 4). The rate of loss is expected to be highest in the Mt Gibson and Salutation Island populations and lowest at St Peter Island.

Discussion

We have shown loss of genetic diversity, and increased inbreeding and divergence, in translocated populations of the GSNR. Importantly, the observed amounts of diversity loss, inbreeding and divergence vary among translocated populations. The high-resolution SNP data provide a basis for a strategic approach to genetic supplementation of these populations to maximise genetic diversity, and suggest the most appropriate sources for future translocations. These are outlined below.

Candidate populations for supplementations

All translocated populations of GSNR have lost diversity compared to the original source population on the Franklin Islands, and effective population sizes were all small (maximum Ne = 46.9). Frankham et al. (2014) found that an effective population size of at least 100 was needed to avoid inbreeding depression in the short term and Ne > 1000 was needed to maintain evolutionary potential in perpetuity. Our analysis shows that all extant translocated populations of the GSNR are expected to lose diversity in coming generations (Fig. 4; Table 4). Thus, assisted gene flow by intermixing populations would benefit all translocated GSNR populations. However, in the interest of prioritization, two populations in particular stand out as candidates for supplementation in the immediate future based on their within-population genetic R, estimated Ne, divergence from the source population, and difference in genetic diversity and inbreeding compared to the Franklin Islands.

Firstly, the Salutation Island population has the lowest diversity across all measures (AR, HE and HO, Table 2) and was the only population with significantly higher inbreeding (i.e. higher average individual F, Fig. 2) than the Franklin Islands. In addition, it had the highest divergence (FST) from the Franklin Islands (Table 3), the highest within-population average genetic R (Fig. 3) and the lowest Ne (Table 4) of the successfully established translocated populations (i.e. excluding Mt Gibson). The low number of individuals used to found the Salutation Island population (N = 40) may have contributed to loss of diversity compared to other sites. These 40 individuals were descended from just 11 founders of the Monarto colony, with an estimated founder genome equivalent (the effective number of founders accounting for uneven contributions, [Lacy 1989]) of only 4.26 (unpublished Adelaide Zoo report 1994; SM Table 2). The smaller estimated census size (< 500, potentially driven by the smaller than average area of the site, Table 1) and/or the longer time since translocation (26 years) may also have contributed to the low diversity of GSNR at Salutation Island. Finally, intermittent trapping on the island suggests a fluctuating population size (Short et al. 2019), which may contribute to low Ne and loss of genetic diversity over time (Frankham et al. 2010). Given these results, we recommend supplementation of the Salutation Island population; in the next section below we suggest the most appropriate sources.

Secondly, the establishing Mt Gibson population also showed significant loss of diversity (as measured by AR and HE, Table 2), the highest within-population average genetic R (Fig. 3), the second highest FST in comparisons to the Franklin Islands (Table 3) and the lowest Ne (Table 4) of all sampled populations. Although the Mt Gibson population was, like Salutation Island, founded by a small number of individuals (N = 39), the translocation occurred more recently (i.e. 2011). Therefore, these results are most likely driven by an observed decline in population size. Specifically, after an initial increase to > 60 individuals during the ~ 6 months after founding, the population decreased (attributable to predation and/or heat stress) to fewer than 20 individuals prior to sampling in 2016 (Short et al. 2019). Thus, supplementation of the Mt Gibson population is warranted and has in fact been undertaken twice (Table 1). Further genetic monitoring is needed to assess whether these translocations led to genetic supplementation.

Mt Gibson shows some unusual patterns that we have not been able to explain with current data. It is the only population to show heterozygosity excess (HO higher than HE), and despite clear signals of diversity loss at other measures, did not have significantly higher inbreeding than the Franklin Islands. Admixture could drive this, but we did not find convincing signals of inter-breeding, suggesting that all six sampled individuals were descended from the original West Franklin founders. This is not an unexpected result as only three individuals in our sample set were potential F1 hybrids. Wider and more recent sampling is necessary to determine whether the Alice Springs Desert Park individuals bred after release at Mt Gibson. Other possibilities include inbreeding depression, and/or biased sex ratio among breeders. Inbreeding depression may lead to heterozygote advantage at neutral loci linked to functional sites, particularly in small populations with increased linkage disequilibrium (Hill and Robertson 1968; Wright 1969). Large biases in sex ratio among breeders can also lead to heterozygote excess (Robertson 1965; Tarr et al. 2000). Sex ratio bias at Mt Gibson could be driven by greater male mortality during the population decline at that site, combined with polygyny or inbreeding avoidance. Additional field and genetic studies are needed to test these ideas, but we do not believe these unusual results negate our recommendation that the Mt Gibson population requires supplementation.

Appropriate sources for supplementation

The negative average genetic R across all pairs of populations (Table 3) shows that moving individuals between any populations to breed will likely result in increased genetic diversity (as measured by heterozygosity). However, some populations are more appropriate than others.

The Franklin Islands are the most appropriate source as they have the highest genetic diversity and thus represent the largest proportion of the total species diversity (Weeks et al. 2016). They are also most likely to harbour alleles that have been lost (through founder events and/or genetic drift) in the translocated populations (López-Cortegano et al. 2019). Our clustering and divergence analysis shows that the two islands are detectably (albeit weakly) differentiated (Table 3, SM Figs. 3 and 4); as such, sourcing individuals from both islands during future translocations is important for capturing the highest amount of diversity. However, our results must be tempered by the fact that our samples are from 1994. While these samples allow us to estimate loss of diversity since translocations commenced, we cannot be sure that the current population maintains the same level of genetic diversity without contemporary sampling. Additionally, risks of overharvesting this population must be taken into account. An updated survey of population size and genetic diversity on the Franklin Islands would be useful to evaluate these risks.

Similarly, while we found that the Reevesby Island population has many characteristics that recommend it as a source (i.e. similar levels of inbreeding and average relatedness, the least difference in diversity and low divergence from the Franklin Island populations), our samples are from 1999. Our assessment of likely change in HE over time shows that we expect diversity at Reevesby Island today to have decreased to below contemporary levels at Arid Recovery and St Peter Island (Fig. 4; Table 4). During the mid-1990s, irruptive population dynamics were observed on Reevesby Island (Short et al. 2019) and, if such dynamics continued after sampling in 1999, we expect further decreased Ne and genetic diversity in the contemporary population. Contemporary sampling at Reevesby Island is needed to test this prediction.

The St Peter Island and Arid Recovery populations had the two lowest levels of diversity loss of the contemporarily sampled populations, and the two largest Ne estimates. Although both these populations had significantly higher average within-population genetic R than the Franklin Islands, they do not seem to have experienced increased inbreeding. Importantly, both St Peter Island and Arid Recovery had among the highest divergence and lowest between-population average genetic R when compared to the Salutation Island and Mt Gibson populations. This indicates that targeted gene flow between St Peter Island/Arid Recovery and Salutation Island/Mt Gibson would lead to a significant gain in diversity, as measured by heterozygosity, and suggests that translocations between these pairs of populations would be appropriate (Wang 2005). In fact, individuals from St Peter Island were translocated to Mt Gibson in 2018 to reinforce genetic diversity.

For the other translocated populations that we have not identified as priorities but that would nonetheless benefit from supplementation, we suggest the most appropriate sources are those that have the lowest between-population genetic R and/or highest divergence as measured by FST when compared to the recipient population (Table 3). Thus Table 3 provides a guide for conservation practitioners planning supplementation amongst the GSNR populations. However, we again caution that the Reevesby and Franklin Islands populations require more recent sampling.

Salutation Island and Mt Gibson are the two most diverged populations (highest FST and low between-population average genetic R), which might suggest that they are good candidates for cross-translocation; however, neither is an appropriate source population, owing to: (i) the high inbreeding at Salutation Island; (ii) low diversity in both populations; and (iii) current small Ne and census size at Mt Gibson.

When to supplement and how many animals to transfer

We have identified priority populations for supplementation, and suggest that all translocated populations would benefit from genetic reinforcement based on the expectation that inbreeding and diversity loss will increase the risk of long-term population extirpation (Frankham et al. 2017). In certain management situations, it may be desirable to have measurable goals or thresholds of genetic diversity that would signal the need for supplementation. This raises the question of how much genetic diversity is enough? Commonly cited general guidelines could be used to answer this. These guidelines usually recommend goals of maintaining 90% or more of source diversity in the translocated populations (Lacy 1989; Allendorf and Ryman 2002; Weeks et al. 2011). However, such guidelines are somewhat arbitrary and we have therefore avoided using them in this study. How the magnitude of diversity loss and inbreeding translates into fitness and population sustainability for the GSNR is unknown and cannot be ascertained with genetic data alone. Furthermore, varying levels of stress and/or purging efficiency may lead to varying thresholds of tolerance to diversity loss and inbreeding across the GSNR populations (Keane et al. 1996; Joron and Brakefield 2003; Schou et al. 2015; Gooley et al. 2017; Robinson et al. 2018). Field-based studies are necessary to ascertain the true impact of our measured genetic changes on the fitness of GSNR in the wild (as measured by, for example, fecundity and/or survival), and to define thresholds for loss of genetic diversity that indicate the need for intervention.

A related question is then, how many animals to transfer between populations? Again, general guidelines could be used. To minimise the loss of genetic diversity while allowing for local adaptation, Mills and Allendorf (1996) show that between one and ten migrants per generation are appropriate, depending on various characteristics of the source and recipient populations. Subsequent work has shown that under fluctuating population size, the number of migrants per generation may need to be increased to 20 (Vucetich and Waite 2000), and that when there are likely to be unequal contributions of the migrants to the recipient population (lower effective number of migrants), the total number of migrants may need to be higher again (Wang 2004). Simulation studies based on specific conservation programs and species have generally agreed with these guidelines (Grueber and Jamieson 2008; Pacioni 2014; Wajiki et al. 2018). However, supplementation occurring once every generation, or even once every year, represents a large amount of effort, which may not be realistic for most conservation programs, including the GSNR. Future work should include simulation studies that determine the optimum frequency of transfers and number of migrants per transfer for the GSNR, while taking into account external factors that may limit these interventions (Caballero et al. 2010; Pacioni et al. 2019).

Risk of outbreeding depression

A common concern among conservation practitioners when planning translocations between populations is the risk of outbreeding depression (Ralls et al. 2018); that is, decreased fitness due to the disruption of either co-adapted gene complexes or local adaptation (Edmands 2007). It is possible that some local adaptation has occurred within GSNR populations. For example, at Arid Recovery, high mortality has been observed in particularly hot summers (Bolton and Moseby 2004), potentially driving selection. Further fieldwork, common garden experiments (in which individuals from different populations are studied under the same, controlled environment (de Villemereuil et al. 2016)) and/or genomic studies are needed to ascertain whether local adaptation has occurred and whether outbreeding depression is a potential risk for GSNR. Despite the need for further research, we do not believe that it is necessary to wait to supplement the Mt Gibson or Salutation Island populations as it has been shown consistently that the risk of outbreeding depression resulting from admixture relative to the risk of inbreeding depression due to inaction is low (Frankham 2015; Weeks et al. 2016; Frankham et al. 2011).

Conclusion

Translocation as a conservation management strategy is becoming increasingly common and management of genetic issues may be critical to the longer-term success of many of these programs (Frankham et al. 2017). Ultimately, genetics is one of many factors in species conservation. Moving individuals between locations poses risk that must be weighed against likely benefits, given the available knowledge and resources. Our genomic dataset has provided the first species-wide assessment of genetic diversity in GSNR, enabling us to identify the GSNR populations most in need of supplementation and the most appropriate sources. Future work should consider how ecological and environmental characteristics may lead to varying diversity outcomes, enabling better selection of future translocation sites and strategies. Our data and results represent a resource that can be consulted during future conservation planning for this species, allowing genetic diversity outcomes to be assessed alongside other considerations in an integrated manner to support evidence-based decisions.

Data availability

All de-multiplexed raw sequencing data are available from NCBI’s sequence read archive (accession number: PRJNA389954).

References

Allendorf FW, Ryman N (2002) The role of genetics in population viability. In: Beissinger SR, McCullough DR (eds) Population viability analysis. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 50–85

Biebach I, Keller LF (2009) A strong genetic footprint of the re-introduction history of Alpine ibex (Capra ibex ibex). Mol Ecol 18:5046–5058

Biebach I, Keller LF (2012) Genetic variation depends more on admixture than number of founders in reintroduced Alpine ibex populations. Biol Conserv 147:197–203

Bolton J, Moseby KE (2004) The activity of Sand Goannas (Varanus gouldii) and their interaction with reintroduced greater stick-nest rats (Leporillus conditor). Pac Conserv Biol 10:193–201

Caballero A, Rodríguez-Ramilo ST, Ávila V, Ferdandez J (2010) Management of genetic diversity of subdivided populations in conservation programmes. Conserv Genet 11:409–419

Catchen JM, Amores A, Hohenlohe PA, Cresko WA, Postlethwait JH (2011) Stacks: building and genotyping loci de novo from short-read sequences. G3 1:171–182

Catchen JM, Hohenlohe PA, Bassham S, Amores A, Cresko WA (2013) Stacks: an analysis tool set for population genomics. Mol Ecol 22:3124–3140

Copley P (1988) The stick-nest rats of Australia: a final report to World Wildlife Fund (Australia). Department of Environment and Planning, South Australian Government, Adelaide

Copley P (1994) Translocations of native vertebrates in South Australia: a review. In: Serena M (ed) Reintroduction biology of Australian and New Zealand Fauna. Surrey Beatty and Sons, Sydney, pp 35–42

Copley P (1999a) Natural histories of Australia’s stick-nest rats, genus Leporillus (Rodentia: Muridae). Wildl Res 26:13–539

Copley P (1999b) Review of the recovery plan for the greater stick-nest rat. Leoprillus conditor, Department for Environment, Heritage and Aboriginal Affairs, South Australian Government, Adelaide

Crnokrak P, Roff DA (1999) Inbreeding depression in the wild. Heredity 83:260–270

Do C, Waples RS, Peel D, Macbeth GM, Tillett BJ, Ovenden JR (2014) NeEstimator v2: re-implementation of software for the estimation of contemporary effective population size (Ne) from genetic data. Mol Ecol Res 14:209–214

Edmands S (2007) Between a rock and a hard place: evaluating the relative risks of inbreeding and outbreeding for conservation and management. Mol Ecol 16:463–475

Foll M, Gaggiotti O (2008) A genome-scan method to identify selected loci appropriate for both dominant and codominant markers: a bayesian perspective. Genetics 180:977–993

Frankham R (2015) Genetic rescue of small inbred populations: meta-analysis reveals large and consistent benefits of gene flow. Mol Ecol 24:2610–2618

Frankham R, Lees K, Montgomery ME, England PR, Lowe EH, Briscoe DA (1999) Do population size bottlenecks reduce evolutionary potential? Anim Conserv 2:255–260

Frankham R, Ballou JD, Briscoe DA (2010) Introduction to conservation genetics, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, New York

Frankham R, Ballou JD, Eldridge MDB, Lacy RC, Ralls K, Dudash MR, Fenster CB (2011) Predicting the probability of outbreeding depression. Conserv Biol 25:465–475

Frankham R, Bradshaw CJA, Brook BW (2014) Genetics in conservation management: revised recommendations for the 50/500 rules, red list criteria and population viability analyses. Biol Conserv 170:56–63

Frankham R, Ballou JD, Ralls K, Eldridge M, Dudash MR, Fenster CB, Lacy RC, Sunnucks P (2017) Genetic management of fragmented animal and plant populations. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Gooley R, Hogg CJ, Belov K, Grueber CE (2017) No evidence of inbreeding depression in a Tasmanian devil insurance population despite significant variation in inbreeding. Sci Rep 7:1–11

Goudet J (2005) Hierfstat, a package for r to compute and test hierarchical F-statistics. Mol Ecol Notes 5:184–186

Grueber CE, Jamieson IG (2008) Quantifying and managing the loss of genetic variation in a free-ranging population of takahe through the use of pedigrees. Conserv Genet 9:645–651

Hardy OJ (2003) Estimation of pairwise relatedness between individuals and characterization of isolation-by-distance processes using dominant genetic markers. Mol Ecol 12:1577–1588

Hedrick PW, Lacy RC (2015) Measuring relatedness between inbred individuals. J Hered 106:20–25

Helyar SJ, Hemmer-Hansen J, Bekkevold D, Taylor MI, Ogden R, Limborg MT, Cariani A, Maes GE, Diopere E, Carvalho GR, Nielsen EE (2011) Application of SNPs for population genetics of nonmodel organisms: new opportunities and challenges. Mol Ecol Res 11:123–136

Hill WG, Robertson A (1968) Linkage disequilibrium in finite populations. Theor Appl Genet 38:226–231

Jombart T (2008) adegenet: a R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 24:1403–1405

Jones AT, Ovenden JR, Wang Y-G (2016) Improved confidence intervals for the linkage disequilibrium method for estimating effective population size. Heredity 117:217–223

Jorde PE, Ryman N (2007) Unbiased estimator for genetic drift and effective population size. Genetics 177:927–935

Joron M, Brakefield PM (2003) Captivity masks inbreeding effects on male mating success in butterflies. Nature 424:191–194

Keane B, Creel SR, Waser PM (1996) No evidence of inbreeding avoidance or inbreeding depression in a social carnivore. Behav Ecol 7:480–489

Korneliussen TS, Moltke I (2015) NgsRelate: a software tool for estimating pairwise relatedness from next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31:4009–4011

Lacy RC (1989) Analysis of founder representation in pedigrees: founder equivalents and founder genome equivalents. Zoo Biol 8:111–123

López-Cortegano E, Pouso R, Labrador A, Pérez-Figueroa A, Fernández J, Caballero A (2019) Optimal management of genetic diversity in subdivided populations. Front Genet 10:843

Margan SH, Nurthen RK, Montgomery ME, Woodworth LM, Lowe EH, Briscoe DA, Frankham R (1998) Single large or several small? Population fragmentation in the captive management of endangered species. Zoo Biol 17:467–480

Mastretta-Yanes A, Arrigo N, Alvarez N, Jorgensen TH, Piñero D, Emerson BC (2015) Restriction site-associated DNA sequencing, genotyping error estimation and de novo assembly optimization for population genetic inference. Mol Ecol Res 15:28–41

McLennan EA, Grueber CE, Wise P, Belov K, Hogg CJ (2020) Mixing genetically differentiated populations successfully boosts diversity of an endangered carnivore. Anim Conserv. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12589

Mills LS, Allendorf FW (1996) The one-migrant‐per‐generation rule in conservation and management. Conserv Biol 10:1509–1518

Morris KD (2000) The status and conservation of native rodents in Western Australia. Wildl Res 27:405–419

Moseby KE, Bice JK (2004) A trial re-introduction of the greater stick-nest rat (Leporillus conditor) in arid South Australia. Ecol Manage Restor 5:118–124

Moseby KE, Read JL (2006) The efficacy of feral cat, fox and rabbit exclusion fence designs for threatened species protection. Biol Conserv 127:429–437

Moseby KE, Read JL, Paton DC, Copley P, Hill BM, Crisp HA (2011) Predation determines the outcome of 10 reintroduction attempts in arid South Australia. Biol Conserv 144:2863–2872

Nazareno AG, Bemmels JB, Dick CW, Lohmann LG (2017) Minimum sample sizes for population genomics: an empirical study from an Amazonian plant species. Mol Ecol Res 17:1136–1147

Pacifici M, Santini L, di Marco M, Baisero D, Francucci L, Marasini GG, Visconti P, Rondinini C (2013) Generation length for mammals. Nat Conserv 5:89–94

Pacioni C (2014) Modelling woylie (Bettongia penicillata) population genetics to inform management strategies. WWF-Australia, Perth

Pacioni C, Wayne AF, Page M (2019) Guidelines for genetic management in mammal translocation programs. Biol Conserv 237:105–113

Page M, Spence-Bailey L, Legge S, Armstrong D, Morris K (2011) Translocation proposal for greater stick-nest rat (Leporillus conditor). Australian Wildlife Conservancy, Perth

Pedler L, Copley P (1993) Re-introduction of stick-nest rats to Reevesby Island, South Australia. Department of Environment and Land Management, South Australian Government, Adelaide

Pew J, Muir PH, Wang J, Frasier TR (2015) Related: an R package for analysing pairwise relatedness from codominant molecular markers. Mol Ecol Res 15:557–561

Pimm SL, Dollar L, Bass OL (2006) The genetic rescue of the Florida panther. Anim Conserv 9:115–122

Poland JA, Brown PJ, Sorrells ME, Jannink J-L (2012) Development of high-density genetic maps for barley and wheat using a novel two-enzyme genotyping-by-sequencing approach. PLoS ONE 7:e32253

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P (2000) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155:945–959

Procter J (2007) Husbandry guidelines–greater stick nest rat Leporillus conditor [Unpublished Report]. Alice Springs Desert Park, Alice Springs

Pruett CL, Winker K (2008) The effects of sample size on population genetic diversity estimates in song sparrows Melospiza melodia. J Avian Biol 39:252–256

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, Sklar P, De Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC (2007) PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 81:559–575

R Core Team (2019) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed Jan 2020

Ralls K, Ballou JD, Dudash MR, Eldridge MDB, Fenster CB, Lacy RC, Sunnucks P, Frankham R (2018) Call for a paradigm shift in the genetic management of fragmented populations. Conserv Lett 11:e12412

Rivero ERC, Neves AC, Silva-Valenzuela MG, Sousa SOM, Nunes FD (2006) Simple salting-out method for DNA extraction from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. Pathol Res Pract 202:523–529

Robertson A (1965) The interpretation of genotypic ratios in domestic animal populations. Anim Sci 7:319–324

Robinson AC (1975) The stick-nest rat, Leporillus conditor, on Franklin Island, Nuyts Archipelago, South Australia. Aust Mammal 1:319–327

Robinson JA, Brown C, Kim BY, Lohmueller KE, Wayne RK (2018) Purging of strongly deleterious mutations explains long-term persistence and absence of inbreeding depression in island foxes. Curr Biol 28:3487–3494

Schou MF, Loeschcke V, Kristensen TN (2015) Inbreeding depression across a nutritional stress continuum. Heredity 115:56–62

Schwartz MK, Luikart G, Waples RS (2007) Genetic monitoring as a promising tool for conservation and management. Trends Ecol Evol 22:25–33

Short J, Copley P, Ruykys L, Morris K, Read J, Moseby KE (2019) Review of translocations of the greater stick-nest rat (Leporillus conditor): lessons learnt to facilitate ongoing recovery. Wildl Res 46:455–475

Tarr CL, Ballou JD, Morin MP, Conant S (2000) Microsatellite variation in simulated and natural founder populations of the Laysan finch (Telespiza cantans). Conserv Genet 1:135–146

Thavornkanlapachai R, Mills HR, Ottewell K, Dunlop J, Sims C, Morris K, Donaldson F, Kennington WJ (2019) Mixing genetically and morphologically distinct populations in translocations: asymmetrical introgression in a newly established population of the boodie (Bettongia lesueur). Genes 10:729

Tonkin-Hill G, Lee S (2016) Starmie: population structure model inference and visualisation (Version 0.1.2) [R v3.3.0]. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/starmie. Accessed Jan 2020

Tracy LN, Wallis GP, Efford MG, Jamieson IG (2011) Preserving genetic diversity in threatened species reintroductions: how many individuals should be released? Anim Conserv 14:439–446

Villemereuil de P, Gaggiotti O, Mouterde M, Till-Bottraud I (2016) Common garden experiments in the genomic era: new perspectives and opportunities. Heredity 116:249–254

Vucetich JA, Waite TA (2000) Is one migrant per generation sufficient for the genetic management of fluctuating populations? Anim Conserv 3:261–266

Wahlund S (1928) Zusammensetzung von populationen und Korelationsers-cheinungen vom standpunkt der Venerbungslehre aus betrachtet. Hereditas 11:175–195

Wajiki Y, Kaneko Y, Sugiyama T, Yamada T. Iwaisaki H (2018) An estimation of number of birds to be consecutively released in the reintroduction of Japanese Crested Ibises (Nipponia nippon). Wilson J Ornithol 130:874–880

Walther BA, Moore JL (2005) The concepts of bias, precision and accuracy, and their use in testing the performance of species richness estimators, with a literature review of estimator performance. Ecography 28:815–829

Wang J (2002) An estimator for pairwise relatedness using molecular markers. Genetics 160:1203–1215

Wang J (2004) Application of the one-migrant‐per‐generation rule to conservation and management. Conserv Biol 18:332–343

Wang J (2005) Monitoring and managing genetic variation in group breeding populations without individual pedigrees. Conserv Genet 5:813–825

Wang J (2017) Estimating pairwise relatedness in a small sample of individuals. Heredity 119:302–313

Wang J (2018) Effects of sampling close relatives on some elementary population genetics analyses. Mol Ecol Res 18:41–54

Waples RS (1989) Temporal variation in allele frequencies: testing the right hypothesis. Evolution 43:1236–1251

Waples RS, Do C (2008) LDNE: a program for estimating effective population size from data on linkage disequilibrium. Mol Ecol Res 8:753–756

Weeks AR, Sgro CM, Young AG, Frankham R, Mitchell NJ, Miller KA, Byrne M, Coates DJ, Hoffmann AA (2011) Assessing the benefits and risks of translocations in changing environments: a genetic perspective. Evol Appl 4:709–725

Weeks AR, Stoklosa J, Hoffmann AA (2016) Conservation of genetic uniqueness of populations may increase extinction likelihood of endangered species: the case of Australian mammals. Front Zool 13:31

Weeks AR, Heinze D, Perrin L, Stoklosa J, Hoffmann AA, van Rooyen A, Kelly T, Mansergh I (2017) Genetic rescue increases fitness and aids rapid recovery of an endangered marsupial population. Nat Commun 8:1–6

Weir BS, Cockerham CC (1984) Estimating F-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution 38:1358–1370

White LC, Moseby KE, Thomson VA, Donnellan SC, Austin JJ (2018) Long-term genetic consequences of mammal reintroductions into an Australian conservation reserve. Biol Conserv 219:1–11

Woinarski J, Burbidge AA (2016) Greater stick-nest rat, Leporillus conditor. http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/11634/0. Accessed 2 June 2017

Wright S (1969) The theory of gene frequencies. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. We wish to thank Kim Branch (Western Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions) for sourcing samples from Salutation Island, Katherine Tuft (Arid Recovery) for helping to co-ordinate trapping at Arid Recovery, Paul Gooding (Australian Genome Research Facility) for sequencing guidance, the Nature Foundation of South Australia for supporting this research, and the anonymous reviewers who provided helpful comments to improve the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Nature Foundation of South Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

White, L.C., Thomson, V.A., West, R. et al. Genetic monitoring of the greater stick-nest rat meta-population for strategic supplementation planning. Conserv Genet 21, 941–956 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-020-01299-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-020-01299-x