Abstract

Family and social support can enhance our perception of our ability to cope with stressful life events, as well as our psychological flexibility and mental well-being. The main goal of this unique study was to explore how a complex interplay of family, social, and personal factors contribute to mental well-being and life satisfaction. We hypothesized that differentiation of self (DoS) and social support (from family, friends, and significant others) would be positively associated with mental well-being and life satisfaction through the mediation of resilience. The sample included 460 participants (mean age 45.2; 236 males), who filled out questionnaires examining DoS, social support, resilience, mental well-being, and life satisfaction. In light of gender disparities evident in both existing literature and the current study, we analyzed the model separately for women and men. The findings revealed a mediation model, indicating that resilience mediated the relationship between two dimensions of DoS (emotional reactivity and I-position) and mental well-being for males, while DoS and social support contributed to women’s mental well-being without the mediation of resilience. Two factors emerged as contributors to improved mental well-being and life satisfaction: DoS and social support. Specifically, DoS was deemed important for both men and women, while social support emerged as a crucial dimension mainly for women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In today’s world, individuals frequently encounter a multitude of stressors that can jeopardize their mental well-being and consequently have a detrimental impact on their physical health, ultimately diminishing their overall quality of life (Peleg & Peleg, 2023). Support systems, comprising care from family, friends, and significant others, play a pivotal role in helping individuals adapt to and navigate challenging situations and stressors (Saltzman et al., 2020). Such systems have been associated with an important family pattern – differentiation of self (DoS) – which holds the potential to enhance resilience in certain individuals (MacKay, 2017). Nonetheless, the precise mechanisms underpinning this connection remain unclear, and what might benefit various individuals in this context remains uncertain. In the current study, we extended the scope of Family Systems theory to encompass mental well-being and life satisfaction, assuming that vulnerability to low well-being and life satisfaction is affected not only by resilience, but also by DoS and social support, on which resilience depends. Going a step further, our research examined whether and how both family and social support systems could contribute to enhancing mental well-being and life satisfaction through the mediation of resilience for individuals of both genders. Hence, this study aimed to uncover the intricate web of relationships among social, family, and personal factors contributing to the enhancement of mental well-being and life satisfaction.

Social Support

Social support is defined as a network of social relationships encompassing support from family, friends, and significant others. It serves as a protective factor fostering the belief, that individuals can receive emotional, informational, and instrumental assistance (Saltzman et al., 2020), thereby bolstering positive feelings and outcomes. Conversely, when social support is inaccessible, people experience higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression (Tindle et al., 2022).

Gender differences in social support have been explored in several studies. For example, women reported having higher levels of social support than men. These differences have been explained by socialization experiences and social roles associated with gender (Matud et al., 2003). In another study, women reported higher levels of support than men from all sources (e.g., parent, friends) except fathers (Galambos et al., 2018).

Individuals who received social support from multiple sources, such as family, friends, and colleagues, reported better mental well-being and lower emotional distress (Leahy-Warren et al., 2011). The family, as a significant source of social support, plays a crucial role, with its dynamic nature providing a vital context for studying various processes and outcomes of support (Graham & Brisini, 2021). Notably, social support has been found to be positively associated with one of the most pivotal family patterns – DoS – suggesting that higher levels of support and DoS correspond to greater personal growth (Abu-Sharkia et al., 2020).

Differentiation of Self (DoS)

Family Systems theory, developed by Bowen (Bowen, 1978; Kerr & Bowen, 1988), assumes that individuals function not in isolation, but in the context of meaningful relationships with family, loved ones, and friends. The theory emphasizes the interrelated and socially embedded nature of individual life, providing a conceptual framework that enables understanding of the individual’s functions within and outside the family (Kerr & Bowen, 1988; Skowron, 2004).

This theory asserts that behavioral, emotional, and cultural patterns are passed down from generation to generation. One of the most important patterns contributing to mental and physical health is DoS, which operates on two levels. At the interpersonal level, it entails the individual’s ability to balance intimacy and autonomy in relationships with significant others. At the intrapersonal level, it refers to the ability to balance mental and emotional functioning when dealing with stressful life events, without being emotionally overwhelmed (Kerr & Bowen, 1988).

DoS includes four dimensions: emotional reactivity, I-position, emotional cutoff, and fusion with others. Emotional reactivity describes people’s automatic emotional responses to stressful events and their inability to remain calm in stressful situations. I-position refers to individuals’ ability to stick to their needs, thoughts, and feelings. Emotional cutoff taps individuals’ tendency to isolate themselves physically, emotionally, and verbally so as to regulate their emotions and manage tense relationships. Finally, fusion with others reflects the tendency to form symbiotic and dependent relationships. Well-differentiated individuals can invest energy in dealing with life’s tasks, cope effectively with stressful situations, and regulate their emotions. Conversely, poorly differentiated people find it hard to manage interpersonal interactions effectively. They have difficulty regulating their emotions and using effective coping strategies, leading to a poor quality of life (Kerr & Bowen, 1988). Recent studies have revealed gender differences in these dimensions. In most studies, women tended to report higher levels of emotional reactivity and fusion with others (e.g., Peleg, 2022), while men tended to report higher levels of emotional cutoff (e.g., Peleg & Peleg, 2023).

Low DoS has been found to predict health and mental problems, such as physiological symptoms (Peleg, 2002; Skowron & Friedlander, 1998), eating disorders (Peleg et al., 2022), diabetes (Peleg, 2022), poor psychological health (Jankowski et al., 2022), low life satisfaction (Biadsy-Ashkar & Peleg, 2013; Moza et al., 2021), anxiety (e.g., Peleg & Grandi, 2019), and difficulties in emotional regulation (Peleg & Peleg, 2023). Moreover, DoS has been associated with subjective well-being through the mediation of certain dimensions of positive coping, such as self-construal (Houaoglu & Işık, 2022), self-compassion, and cognitive flexibility (Okan & Deniz, 2022). An essential indicator of positive coping, which has been found to be associated with DoS, is resilience (Sadeghi et al., 2020).

Resilience, Mental Well-Being, and Life Satisfaction

Resilience is defined as the ability to recover after experiencing emotional distress (Garmezy, 1991). It describes personality traits and adaptability that help people cope with challenging circumstances (Masten, 2001). Resilience is considered a crucial contributor to the individual’s psychological well-being (Bajaj & Pande, 2016). Frydenberg’s works (2002) highlight the importance of resilience in contemporary society, especially in managing the stresses of everyday life and decreasing the trend of rising depression rates. Her research indicates that participation in the COPE-Resilience program leads to prosocial behaviors and positive coping strategies, tending to be more empathetic (e.g., Soliman et al., 2021).

Gender differences in resilience have been explored in several studies, which indicated that men tend to have higher levels than women (Monticone, 2023). In South Africa, men exhibited higher financial resilience behavior than women (Zeka & Alhassan, 2023). A study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that men reported higher levels of psychological resilience than women, particularly in domains such as meaningfulness, self-reliance, perseverance, and existential aloneness (Sardella et al., 2022).

According to Walsh (2017), there is compelling evidence that the family is one of the most important factors affecting resilience. “Family resilience” denotes the family’s capacity to uphold positive relationships, provide mutual support, and confront diverse social, economic, and personal challenges with the aim of evolving from them. Effective communication plays a pivotal role in navigating difficulties and achieving success, especially during periods of crisis and stress, when communication breakdowns are common. Resilience can be nurtured through adversity, presenting individual with opportunities to find and cultivate their inner strengths and facilitating both the giving and receiving of support. Families that encounter crises often find that their relationships deepen and become more affectionate through shared coping experiences.

Research has consistently demonstrated that healthy and empowering family relationships help individuals cope with stress, pressures, and risks (Wright et al., 2013). Moreover, higher levels of DoS have been related to greater resilience and hope (Sadeghi et al., 2020). Resilience has also been identified as a mediator in the relationships between mental well-being and various emotional and cognitive factors, such as meaning in life (Rasheed et al., 2022), anxiety (Hong et al., 2022), hope (Yıldırım & Arslan, 2022), and happiness (Yıldırım & Belen, 2018). Furthermore, resilience has been shown to enhance the individual’s ability to cope with challenges and emotional distress, thereby improving subjective well-being (Bajaj & Pande, 2016). High mental well-being has been found to enable development of the individual’s personal, occupational, and social potential (Zautra et al., 2010). Conversely, poor mental well-being has been linked to increased dissatisfaction, stress, depression, and loneliness (Kraiss et al., 2020).

Growing evidence has documented strong associations between life satisfaction, favorable health, and mental well-being (Nakamura et al., 2022). Life satisfaction has been found to be a major indicator of mental well-being (Wettstein et al., 2022), which has been shown to affect physical and mental health as well as rational and intellectual functioning (e.g., Kulick & Ryan, 2005). Findings have shown that well differentiated individuals tend to be more satisfied with various aspects of their lives, such as their marital and social relationships (Guo et al., 2022). Nevertheless, a significant number of individuals continue to grapple with effectively navigating stressful life events and maintaining a high level of resilience (Peleg & Peleg, 2023), suggesting that existent theoretical knowledge does not tell the entire story. The widespread challenge of coping with stressors and attaining mental well-being, along with the potential for mental and physical ailments to develop due to diminished quality of life, underscore the need to investigate the specific factors capable of enhancing mental well-being and life satisfaction.

Gender differences have been found with regard to mental well-being. A review of adult literature showed that women often reported higher well-being but also more negative affect, such as anxiety and depression, than men. Along similar lines, gender differences emerged more notably during puberty, with girls experiencing increased anxiety and depression (Hankin & Abramson, 2001). These differences were found to persist into late adulthood, with women tending to report lower well-being and happiness than men, even after accounting for factors like widowhood and socioeconomic status (Diener et al., 2018).

Recent studies have also examined gender differences with respect to life satisfaction, with findings often inconclusive, although many point to disparities favoring men. For instance, Joshanloo (2018) identified significant gender differences among predictors such as unemployment, widowhood, perception of corruption in businesses, tertiary education, part-time employment seeking full-time, and social status, with inconsistencies across genders, favoring men. Similarly, a comprehensive meta-analysis by Chen et al. (2020) indicated relatively stable life satisfaction levels across genders, with slightly higher levels for male children and adolescents than females.

The Present Study

In light of studies indicating that mental well-being and life satisfaction may significantly contribute to mental and physical health, there is a need to further investigate factors that have received insufficient attention and may enhance life satisfaction and mental well-being (Moksnes et al., 2020). Additionally, considering the connections reported in the literature between DoS, social support, and mental well-being (e.g., Saltzman et al., 2020; Tindle et al., 2022), it is essential to examine the pathways that may contribute to this relationship. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to explore innovative ideas that could deepen our understanding of the interplay among family patterns, social support, resilience, mental well-being, and life satisfaction. Specifically, we explored whether resilience innovatively acts as a mediator between DoS and social support, on the one hand, and mental well-being and life satisfaction, on the other, with the aim of revealing interactive factors shaping the individual’s psychological state. In addition, recent findings have revealed divergent pathways predicting resilience and life satisfaction between men and women (Joshanloo, 2018).

These findings underscore the varied societal challenges faced by both men and women. Additionally, higher levels of mental well-being and life satisfaction were found among males (Chen et al., 2020). Furthermore, women have reported lower levels of resilience (Sardella et al., 2022) and higher levels of social support (Galambos et al., 2018), fusion with others, and emotional reactivity than men (Peleg & Peleg, 2023). As several of the research variables in the current study varied between genders, it was deemed important to analyze the proposed mediation model separately for women and men. These models have the potential to unveil distinct factors contributing to resilience, mental well-being, and life satisfaction for each gender.

We hypothesized that DoS (emotional reactivity, I-position, emotional cutoff, fusion with others) and social support (family, friends, significant others) would be positively associated with mental well-being and life satisfaction through the mediation of resilience. This mediation model was tested separately for each gender.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited through systematic sampling from all regions of Israel. Inclusion criteria were individuals fluent in reading and writing Hebrew, who did not have learning disabilities that could impede their ability to complete the questionnaires. Of the 482 participants who began filling out the questionnaire, 22 (4.6%) were excluded due to incomplete responses on significant portions of the forms. The final sample included 460 individuals (mean age 45.2, range 19–70; 236 males). The majority were married with children; over half had a post-secondary education; and most were employed in salaried positions (see Table 1).

With respect to sample size, for a linear regression model with 8 predictors (4 DoS, 3 social support and 1 mediator), a size of n = 280 is needed assuming that the independent variable/mediator explains at least 5% of the variance. A sample size of n = 200 would be sufficient assuming that each independent variable explains at least 7% of the variance. If paths a (between the independent variable and mediator) and b (indirect effect of the independent variable through the mediator) are both small, then a sample size of 462 is needed. If path a is medium and b is small, then a sample size of 391 is needed. If both paths are at least medium-sized, then the current sample size is sufficient.

Instruments

The Differentiation of Self Inventory–Revised

(DSI–R) assesses family interactions (Skowron & Friedlander, 1998; Skowron & Schmitt, 2003). This measure, which has been translated to Hebrew (Peleg, 2002, 2008), includes 46 items divided into four subscales: emotional reactivity, I-position, emotional cutoff, and fusion with others. Sample item: “People have remarked that I’m overly emotional” (emotional reactivity). Responses fall on a Likert scale of 1 (not at all like me) to 6 (very much like me). Subscale scores are calculated by averaging mean scores. Higher DoS is indicated by higher means for I-position and lower means for the other three dimensions. Cronbach’s alpha values were α = 0.86, 0.80, 0.83, and 0.73 for emotional reactivity, I-position, emotional cutoff, and fusion with others, respectively.

The Multidimensional Scale of Social Support

(MSPSS) tests subjective evaluation of social support (Zimet et al., 1988). The questionnaire was translated into Hebrew for the present study, using back translation. The 12 items are divided into three scales (four items each): family, friends, and significant others. Sample item: “I get the emotional help and support I need from my family.” Responses fall on a Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Subscale scores are calculated by averaging mean scores, with higher scores indicating greater perceived support. Cronbach’s alpha values were α = 0.94 for the total score and α = .94, 0.94, and 0.93 for family, friends, and significant others, respectively.

The Brief Resilience Scale

(BRS) measures adaptation and the ability to recover from stress (Smith et al., 2008). The instrument was translated into Hebrew for the current study, using back translation. Half of its six items are worded positively, and half are worded negatively. Sample item: “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times.” Responses fall on a Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The score is calculated by averaging all items, taking into account how they are worded, with higher scores indicating greater resilience. Cronbach’s alpha was α = 0.80.

The Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale

(WEMWBS) measures mental well-being (Tennant et al., 2007). The 14-item instrument has been translated into Hebrew (Peleg & Peleg, 2023). Sample item: “I have been feeling optimistic about the future.” Responses fall on a Likert scale of 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). The score is calculated by averaging all items, with a higher score representing higher levels of mental well-being. Cronbach’s alpha was α = 0.93.

The Satisfaction with Life Scale

(SWLS) is a 5-item self-report measure designed for use with adults (Diener et al., 1985). The inventory was translated into Hebrew and adapted for the present study, using back translation. Sample item: “How much do you enjoy your life?” Responses fall on a Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The score was calculated by averaging all items, with a higher score representing greater satisfaction. Cronbach’s alpha was α = 0.88.

Procedure

The study was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and was approved by the ethics committee of the college (202,311 YVC EMEK). After such approval was received, questionnaires were distributed by a survey company and collected in April–May 2022. All participants signed an informed consent form and answered the questions online. Completion of the questionnaires was voluntary. Participants were promised anonymity and discretion and were told they could stop filling out questionnaires at any time.

Statistical Analyses

We ran MANOVAs to test for statistically significant differences in the demographic variables for DoS and social support. Differences in resilience, mental well-being, and life satisfaction between the binary categorical demographic variables were assessed by independent two-sample t-tests. As age was associated with I-position, resilience, and mental well-being (Table 2), we repeated the above analyses using age as a covariate (performing MANCOVA and ANCOVA respectively).

Pearson correlations assessed the associations between age and the study variables, as well as among the variables themselves. This was repeated by gender.

Mediation analysis was conducted with the PROCESS macro (Model 4), using DoS and social support subscales as the independent variables and resilience as a potential mediator. PROCESS produces bias-corrected bootstrap samples (5000 samples) to generate 95% CIs for the indirect effect (IE) of each mediator for each gender. A significant IE is found when the CIs do not include zero. The significance threshold was set at 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 28 (IBM SPSS statistics) and Process for SPSS version 3.1.

Results

All variables were approximately normally distributed, as their skewness and kurtosis were between − 1 and + 1.

Preliminary Analyses: t-Tests and MANOVAs

There was a statistically significant difference between male and female participants in DoS [F(4, 455) = 11.47, p < .001, partial ἠ2 = 0.092], specifically in emotional reactivity [t (458) = 4.60, p < .001], and fusion with others [t(458) = 3.58, p < .001]. Females had higher scores than males in emotional reactivity (mean difference = 0.402, 95% CI: 0.230–0.574), and fusion with others (mean difference = 0.236, 95% CI: 0.107–0.366). There was also a statistically significant gender difference in social support [F(3, 456) = 6.27, p < .001, partial ἠ2 = 0.040], specifically for the support of friends [t(458) = 2.78, p = .006], and significant others [t(458) = 3.80, p < .001]. Females had higher scores than males [friends (mean difference = 0.399, 95% CI: 0.116–0.681; significant others (mean difference = 0.525, 95% CI: 0.253–0.796)]. Resilience also yielded a statistically significant gender difference [F(1, 458) = 7.80, p = .005, partial ἠ2 = 0.017], with females having lower scores than males (mean difference = 0.188, 95% CI: 0.056–0.320). No gender differences were found for the dependent variables of mental well-being [F(1, 458) = 0.57, p = .452, partial ἠ2 = 0.001], or life satisfaction [F(1, 458) = 0.01, p = .922, partial ἠ2 = 0.000]. Table 3 presents the study variables, as well as t-tests of gender differences in each variable.

There was no statistically significant difference between family statuses (i.e., married, single, and other; not shown in table) for DoS [F(8, 910) = 1.58, p = .127, partial ἠ2 = 0.014]. A significant difference in family statuses was found for social support [F(6, 912) = 2.37, p = .028, partial ἠ2 = 0.015], specifically family support [F(2, 457) = 10.28, p = .013, partial ἠ2 = 0.019], although this difference became non-significant after adjusting for age [F(6, 910) = 1.79, p = .098, partial ἠ2 = 0.012]. A statistically significant difference was yielded for resilience [F(2, 457) = 7.70, p < .001, partial ἠ2 = 0.012], with married participants having significantly higher resilience than single ones (mean difference = 0.293, 95% CI: 0.100–0.486). This difference remained after adjusting for age. Finally, a statistically significant difference between family statuses was found for mental well-being [F(2, 457) = 5.97, p = .003, partial ἠ2 = 0.025], and life satisfaction [F(2, 457) = 8.03, p < .001, partial ἠ2 = 0.034], with married participants having significantly greater mental well-being and life satisfaction than single participants (mean difference = 0.272, 95% CI: 0.081–0.463; mean difference = 0.438, 95% CI: 0.155–0.720, respectively). After correcting for age, the difference became non-significant for well-being but remained significant for life satisfaction [F(2, 456) = 6.06, p = .003, partial ἠ2 = 0.026].

With respect to educational level (not shown in table), a statistically significant difference was revealed between participants with and without a college education for DoS [F(4, 455) = 2.92, p = .020, partial ἠ2=0.025], specifically emotional reactivity [t(458) = 10.65, p < .001], emotional cutoff [t(458) = 5.99, p = .015], and fusion with others [t(458) = 6.89, p = .009]. College-educated participants had significantly higher DoS, i.e., lower emotional reactivity (mean difference = 0.289, 95% CI: 0.115–0.464), emotional cutoff (mean difference = 0.196, 95% CI: 0.039–0.354), and fusion with others (mean difference = 0.175, 95% CI: 0.044–0.306). No difference in social support was found between those with and without a college education [F(3, 456) = 1.70, p = .066, partial ἠ2 = 0.011]. A statistically significant difference was also found for resilience [F(1, 458) = 6.14, p = .014, partial ἠ2 = 0.013]: college-educated individuals reported significantly higher resilience than the others (mean difference = 0.168, 95% CI: 0.035–0.300). This remained significant after adjusting for age. No statistically significant difference was found for mental well-being or life satisfaction [F(1, 458) = 0.18, p = .668, partial ἠ2 = 0.000].

With respect to work status, no statistically significant differences were revealed for DoS [F(8, 910) = 0.90, p = .51, partial ἠ2 = 0.008], social support [F(6, 912) = 0.90, p = .80, partial ἠ2 = 0.003], resilience [F(2, 457) = 0.56, p = .002, partial ἠ2 = 0.002], mental well-being [F(2, 457) = 0.01, p = .989, partial ἠ2 = 0.000], or life satisfaction [F(2, 457) = 0.27, p = .762, partial ἠ2 = 0.001].

Relationships between Background and Study Variables: Pearson Correlations

Table 2 presents correlations between age and the study variables. Overall, age was positively correlated with I-position (r = .183, p < .001), resilience (r = .124, p = .01), and mental well-being (r = .139, p = .003), and negatively correlated with fusion with others (r = − .134, p = .004). Thus, older age was related to increased I-position, resilience, and mental well-being. Decreased emotional reactivity, emotional cutoff, and fusion with others were negatively correlated with resilience, mental well-being, and life satisfaction, while I-position and the subscales of social support (family, friends, significant others) were positively correlated with resilience, mental well-being, and life satisfaction. Resilience was positively correlated with well-being and satisfaction. When we repeated the correlation analysis for each gender, similar relationships were found for male participants; for females, resilience was not correlated with the subscales of social support (family, friends, significant others), and fusion with others was not correlated with life satisfaction.

The Mediation Linear Regression Model: A PROCESS Analysis

For both males and females, only emotional reactivity (b = − 0.2237, SE = 0.0638, 95% CI: − 0.3290 to − 0.1183, b = − 0.2047, SE = 0.0685, 95% CI: − 0.3178 to − 0.0915, respectively), and I-position (b = 0.3440, SE = 0.0570, 95% CI: 0.2498 to 0.4383; b = 0.2607, SE = 0.0691 95% CI: 0.1464 to 0.3749, respectively), were found to be significantly associated with resilience, while social support was not for either gender. Thus, resilience can only potentially be a mediator of emotional reactivity and I-position with mental well-being and life satisfaction. Among all participants, resilience was a significant mediator of the relationship between emotional reactivity and mental well-being (b = − 0.0165, SE = 0.0103, 95% CI: − 0.034 to − 0.002), but not a significant mediator of I-position and mental well-being (b = 0.0225, SE = 0.0132, 95t% CI: − 0.002–0.046). The results of the mediation models are presented in Tables 4 and 5.

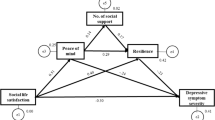

The Mediation Model for Men

Looking at associations with mental well-being among males, resilience was a statistically significant mediator of the relationship between emotional reactivity and mental well-being (indirect effect = − 0.0233, SE = 0.0173, 95% CI: − 0.055 to − 0.008), and I-position and mental well-being (indirect effect = 0.0358, SE = 0.0236, 95% CI: 0.002–0.079). However, I-position, emotional cutoff, and social support from family and friends were significantly associated with mental well-being. Specifically, higher levels of I-position and support from family and friends were associated with increased mental well-being, while higher levels of emotional cutoff were associated with decreased mental well-being (Fig. 1).

Unstandardized regression coefficients and standard errors for men in a mediation model incorporating four DoS and three social support dimensions, with resilience as a mediator. Direct and indirect coefficients from independent variables to outcome variables. ***p < .001, ** p < .01, and * p < .05. Note. − 0.058 (0.055) /-0.035 (0.056), emotional reactivity to mental well-being (direct effect/indirect effect)

The Model for Women

For females resilience was not a significant mediator of the relationship between emotional reactivity and mental well-being (indirect effect = − 0.0109, SE = 0.0120, 95% CI: − 0.038 to 0.011), or I-position and mental well-being, (indirect effect = 0.0139, SE = 0.0150, 95% CI: − 0.013 to 0.046). In fact, resilience itself was not associated with mental well-being (see Table 4). However, as was found for males, I-position and emotional cutoff, as well as support from family and friends, were associated with mental well-being. Higher levels of I-position and support from family and friends contributed to enhanced mental well-being, whereas greater levels of emotional cutoff were associated with diminished mental well-being. Notably, the regression coefficient for I-position was statistically significantly higher for females than males (b = 0.469 vs. b = 0.320, t = 2.01, p = .045). The model for women appears in Fig. 2.

The direct effects model of women’s mental well-being: unstandardized regression coefficients and standard errors (in parentheses) from a model incorporating four DoS and three social support dimensions. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Note. Variables not displayed were not found to be significant but are nonetheless included in the model

With respect to life satisfaction (Table 5), resilience was not a mediator between emotional reactivity and life satisfaction, or I-position and life satisfaction, in either gender. Nor was resilience associated with life satisfaction for males or females. Emotional reactivity and I-position, as well as support from family and friends, were directly associated with life satisfaction (in the case of emotional reactivity, the association was only found among male participants). Increased I-position and support from family and friends improved life satisfaction. For males, an increase in emotional reactivity decreased life satisfaction.

Discussion

The main study goal was to examine whether DoS and social support are associated with mental well-being and life satisfaction through the mediation of resilience. The model was tested separately for men and women. While the mediation model was partially confirmed among men, it did not reach significance among women.

Demographic Results

The examination of demographic variables yielded several results. Life satisfaction was found to be higher among married than single participants, supporting the idea that other factors, such as family status, may affect it. The finding corroborates results indicating that individuals who reported higher levels of positive characteristics in their spousal relationship were more satisfied with their life (e.g., Walker et al., 2023). Marital life likely offers support and security that enhance life satisfaction. We suggest further investigation into how various types of spousal interactions influence life satisfaction.

Regarding age and education, we found that older and more educated people were more differentiated, supporting previous findings (Peleg & Peleg, 2023). Assuming that DoS takes shape and stabilizes when young, we suggest that age and education may increase awareness, which in turn improves DoS. This assumption is worthy of further investigation.

The Mediation Model

A mediation model was observed, partially supporting our research hypothesis, and indicating two different models for males and females. First, it is noteworthy that the independent variables, I-position and social support, were positively correlated. This suggests that individuals who could express their feelings and needs directly, without fearing the opinion and pressure of significant others, were better able to obtain support from them. The results showed that, for males, resilience was a significant mediator of the relationship between two dimensions of DoS, i.e., emotional reactivity and I-position, on the one hand, and mental well-being, on the other. This result partially supports findings indicating that strong parent-child relationships impact individuals’ resilience (Sadeghi et al., 2020). Our findings indicate that men who are emotionally balanced and regulated (emotional reactivity) and who express their emotions, desires, and needs, regardless of pressure from significant others (I-position), report higher resilience, which in turn increases their mental well-being. This aligns with research indicating that resilience is a crucial attribute associated with enhanced subjective well-being (Yıldırım & Arslan, 2022; Yıldırım & Belen, 2018). The results add empirical support to the notion that nurturing family ties can enhance an individual’s ability to navigate life’s challenges.

The results highlight certain likely gender trends in the effects of DoS on mental well-being, through specific indirect paths. Hence, positive relationships between DoS (I-position and emotional cutoff) and mental well-being were evident for both genders, in line with research linking DoS to the cultivation of positive mental health indicators (Frederick et al., 2016). Moreover, positive relationships were yielded between social support (from family and friends) and women’s well-being. Two interesting results can be observed: (1) social support makes a greater contribution to women’s mental well-being; and (2) both DoS and social support contribute to women’s mental well-being without the mediation of resilience. Greater mental well-being is experienced by men and women who express their desires and thoughts, by men and women who typically do not suppress their emotions or distance themselves, and by women who enjoy greater support from family and friends.

The connection between women who utilize social support and mental well-being corroborates findings from previous studies (Hsieh & Tsai, 2019; Reevy & Maslach, 2001). Evolutionarily, women have developed strong social networks as a survival strategy, particularly for raising children and ensuring communal support (Taylor et al., 2000). Biologically, women are more likely to experience higher levels of oxytocin, a hormone that promotes bonding and social connections, especially in response to stress (Carter, 1998). Additionally, research suggests that higher vagally mediated heart rate variability, associated with lower stress vulnerability, is linked to seeking social support, a strategy more commonly used by females (Kvadsheim et al., 2022). Culturally, women are often socialized to be more expressive and to rely on social networks for emotional support. Furthermore, individuals facing chronic illnesses, predominantly women, require emotional and instrumental support, underscoring the importance of social support in challenging situations (Suchocka et al., 2020).

For men only, in addition to the direct links between I-position and emotional cutoff, on the one hand, and mental well-being, on the other, there is also a special significance to the increased resilience that is associated with a high level of DoS, which in turn improves their mental well-being. While the exact reasons for the relationship between resilience and mental well-being among men (but not women) might vary, there are several potential explanations that could shed light on this process. The first has to do with cultural and social norms: indeed, cultural values and beliefs have been found to contribute to gender gaps in various outcomes, such as competitiveness, labor force participation, and performance in various areas (Booth et al., 2019; Tang & Zhao, 2024). These norms can also influence how individuals perceive and express their emotions. Men might face societal expectations to exhibit resilience in the face of adversity, potentially leading them to rely more than women on their resilience as a coping mechanism for maintaining mental well-being. This may be why resilience was activated as a mediator only among men.

A second possible explanation is related to coping strategies. Men and women might employ different strategies to deal with challenges. Men might be more inclined to draw on characteristics of resilience, such as emotional regulation and problem-solving, as a way to manage stressors. Indeed, one study reported that women were more likely than men to use acceptance, self-distraction, positive reframing, and emotional support as coping mechanisms for stressful situations (Cholankeril et al., 2023). This inclination could make resilience a more influential factor in predicting men’s mental well-being.

A third possibility has to do with gendered experiences. Men and women often navigate distinct life experiences, which could impact the relationship between resilience and mental well-being. Factors like workplace dynamics, societal pressures, and gender-specific stressors might interact with resilience differently for each gender, influencing mental well-being outcomes (Peleg, 2022). In short, understanding why resilience predicts mental well-being among men but not women in the current study involves a combination of psychological, cultural, and contextual factors that warrant deeper investigation.

It is interesting to note that resilience did not predict life satisfaction in either gender, refuting previous findings. Nonetheless, DoS did predict it, consistent with some studies (e.g., Biadsy-Ashkar & Peleg, 2013), but only for two dimensions (emotional reactivity and I-position), without the mediation of resilience, and only among men. This may be because the Satisfaction with Life Scale refers not only to psychological issues, but also to other areas, such as socioeconomic status, family status, and work status. These areas may be related to characteristics not examined in the present study, such as appearance, ambitions, persistence, and intellectual functioning.

Limitations

The current study has several limitations. First, we used self-report questionnaires, which are prone to social desirability bias. Future research should incorporate additional assessment tools, such as in-depth interviews, to mitigate this limitation. Second, the Satisfaction with Life Scale includes questions on additional domains, such as family status, which may influence individuals’ responses. This could potentially explain why life satisfaction was not found to be associated with resilience, DoS, or social support. Third, we lack information on the religious or ethnic characteristics of the study sample, which may restrict the generalizability of our findings to broader demographic groups. Forth, the data was collected during a period of COVID-19 restrictions, although the more severe limitations, such as lockdown, had been lifted by then and people had returned to work and school. Nonetheless, this atmosphere may have somewhat influenced responses (particularly gender differences) concerning social support, fusion with others, and resilience, more so than during less challenging times. It is therefore suggested to replicate the research in a period without such restrictions. Finally, it should be noted that the assumptions we used for performing the sample size calculations were conservative, resulting in our models having moderate power. While the mediator, resilience, explained 19.9% and 15.4% of the variance in the well-being outcome, and social support (comprising three variables) explained 22.5% and 21.0% of the variance, the combined variables in DOS explained 10.7% and 19.6% of the variance. Except for I-position and family social support, individual subscales explained less than 5% of the variance, which is slightly lower than our initial assumption of 7%. Additionally, although path a demonstrated a medium effect size, path b showed a small effect size. This suggests that a larger sample size, ideally at least 391 participants per gender, would have been more appropriate to fully capture these effects. We believe these insights highlight areas where future research can build on our findings with a larger sample and enhanced statistical power.

Conclusions

Notwithstanding the above limitations, our findings make several contributions. Theoretically, they shed light on two factors that may contribute to individuals’ mental well-being and life satisfaction: DoS and social support. Moreover, DoS is a significant dimension among men and women alike, while social support is crucial mainly among women. For men, a high level of DoS is an important resource that can increase resilience and consequently mental well-being, whereas for women DoS contributes directly to mental well-being. Hence, the study highlights that resilience plays a significant role in mediating the relationship between two dimensions of DoS (emotional reactivity and I-position) and mental well-being among males only.

Practical Contribution

We suggest that family therapists help clients improve their mental well-being by working on interactions with families of origin and social support systems. Specifically, we strongly recommend increasing I-position, that is, helping patients express their desires and feelings, and fulfill their needs and aspirations, without adhering to external or familial expectations. Additionally, our results suggest that women’s social support systems should be strengthened when they experience poor mental well-being, whereas for men, it would be better to help strengthen their sense of resilience so as to improve their mental well-being. Programs focusing on fostering emotional balance and encouraging open expression of emotions and needs could potentially enhance resilience and subsequently improve mental well-being.

The study emphasizes the significance of family relationships and social support. Educators, caregivers, and parents can take away insights into the long-term benefits of nurturing balanced and communicative family environments that contribute to men’s resilience and mental well-being, and to women’s mental well-being.

In sum, our findings offer valuable insights for both theoretical research and practical interventions. The study’s theoretical and practical contributions provide a comprehensive perspective on the interplay between family dynamics, social support, resilience, mental well-being, and life satisfaction.

Data Availability

The data is accessible from the editors upon a reasonable request.

References

Abu-Sharkia, S., Ben-Ari, O. T., & Mofareh, A. (2020). Secondary traumatization and personal growth of healthcare teams in maternity and neonatal wards: The role of differentiation of self and social support. Nursing & Health Sciences, 22(2), 283–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12710.

Bajaj, B., & Pande, N. (2016). Mediating role of resilience in the impact of mindfulness on life satisfaction and affect as indices of subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 93, 63–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.005.

Biadsy-Ashkar, A., & Peleg, O. (2013). The relationship between differentiation of self and satisfaction with life amongst Israeli women: A cross cultural perspective. Health, 5(9), 1467–1477. https://doi.org/10.4236/health.2013.59200.

Booth, A., Fan, E., Meng, X., & Zhang, D. (2019). Gender differences in willingness to compete: The role of culture and institutions. The Economic Journal, 129(618), 734–764. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12583.

Bowen, M. (1978). Family therapy in clinical practice. Jason Aronson.

Carter, C. S. (1998). Neuroendocrine perspectives on social attachment and love. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 23(8), 779–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(98)00055-9.

Chen, X., Cai, Z., He, J., & Fan, X. (2020). Gender differences in life satisfaction among children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21, 2279–2307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00169-9.

Cholankeril, R., Xiang, E., & Badr, H. (2023). Gender differences in coping and psychological adaptation during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 993. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20020993.

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Tay, L. (Eds.). (2018). Handbook of well-being. Noba Scholar.

Frederick, T., Purrington, S., & Dunbar, S. (2016). Differentiation of self, religious coping, and subjective well-being. Mental Health Religion & Culture, 19, 553–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2016.1216530.

Frydenberg, E. (Ed.). (2002). Beyond coping: Meeting goals, visions, and challenges. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med:psych/9780198508144.001.0001.

Galambos, N. L., Fang, S., Horne, R. M., Johnson, M. D., & Krahn, H. J. (2018). Trajectories of perceived support from family, friends, and lovers in the transition to adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35(10), 1418–1438. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407517717360.

Garmezy, N. (1991). Resilience and vulnerability to adverse developmental outcomes associated with poverty. American Behavioral Scientist, 34(4), 416–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764291034004003.

Graham, D. B., & Brisini, K. S. C. (2021). Social support in families. In A. L. Vangelisti (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of family communication. Routledge.

Guo, X., Huang, J., & Yang, Y. (2022). The association between differentiation of self and life satisfaction among Chinese emerging adults: The mediating effect of hope and coping strategies and the moderating effect of child maltreatment history. International Journal of Environmental & Research Public Health, 19(12), 7106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127106.

Hankin, B. L., & Abramson, L. Y. (2001). Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability–transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin, 127(6), 773–796. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773.

Hong, J., Walid, H., Tarek Abou Ali, M. B., Saleh, N. O., Hammoudi, S. F., Lee, J., Junseok, A., & Jangho, J. (2022). Mediation effect of self-efficacy and resilience on the psychological well-being of Lebanese people during the crises of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Beirut explosion. Frontiers in Psychology, 122. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.733578.

Houaoglu, F. B., & Işık, E. (2022). The role of self-construal in the associations between differentiation of self and subjective well-being in emerging adults. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02527-4.

Hsieh, C. M., & Tsai, B. K. (2019). Effects of social support on the stress–health relationship: Gender comparison among military personnel. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, 1317. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16081317.

Jankowski, P. J., Sandage, S. J., & Crabtree, S. A. (2022). The psychometric challenges of implementing wellbeing assessment into clinical research and practice: A commentary on assessing mental wellbeing using the mental health continuum–short form: A systematic review and meta-analytic structural equation modeling. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 29(4), 457–460. https://doi.org/10.1037/cps0000090.

Joshanloo, M. (2018). Gender differences in the predictors of life satisfaction across 150 nations. Personality and Individual Differences, 135, 312–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.07.043.

Kerr, M., & Bowen, M. (1988). Family evaluation: An approach based on Bowen theory. Norton.

Kraiss, J. T., Klooster, T., Moskowitz, P. M., J. T., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2020). The relationship between emotion regulation and well-being in patients with mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152189.

Kulick, L., & Ryan, P. (2005). Spousal relations, strategies for coping with home–work conflict, and well-being: A comparative analysis of jewish and arab women. Megamot, 43, 633–658. (Hebrew).

Kvadsheim, E., Sørensen, L., Fasmer, O. B., Osnes, B., Haavik, J., Williams, D. P., & Koenig, J. (2022). Vagally mediated heart rate variability, stress, and perceived social support: A focus on sex differences. Stress (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 25(1), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890.2022.2043271.

Leahy-Warren, P., McCarthy, G., & Corcoran, P. (2011). First-time mothers: Social support, maternal parental self-efficacy and postnatal depression. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 388–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03701.x.

MacKay, L. M. (2017). Differentiation of self: Enhancing therapist resilience when working with relational trauma. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 38(4), 637–656. https://doi.org/10.1002/anzf.1276.

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.227.

Matud, M. P., Ibáñez, I., Bethencourt, J. M., Marrero, R., & Carballeira, M. (2003). Structural gender differences in perceived social support. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(8), 1919–1929. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00041-2.

Moksnes, U. K., Bjørnsen, H. N., Eilertsen, M. E. B., & Espnes, G. A. (2020). The role of perceived loneliness and sociodemographic factors in association with subjective mental and physical health and well-being in Norwegian adolescents. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 50(4), 432–439. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494821997219.

Monticone, C. (2023). Gender differences in financial literacy and resilience. In joining forces for gender equality: What is holding us back?. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/a9f80ab9-en.

Moza, D., Lawrie, S. I., Maricuțoiu, L., Gavreliuc, A., & Kim, H. (2021). Not all forms of independence are created equal: Only being independent the right way is associated with self-esteem and life satisfaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 606354. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.606354.

Nakamura, J. S., Delaney, S. W., & Diener, E. (2022). Are all domains of life satisfaction equal? Differential associations with health and well-being in older adults. Quality of Life Research, 31, 1043–1056. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02977-0.

Okan, Y., & Deniz, M. E. (2022). The mediating role of self-compassion and cognitive flexibility in the relationship between differentiation of self and subjective well-being. Cukurova University Faculty of Education Journal, 51(3), 1642–1680. https://doi.org/10.14812/cuefd.1074927.

Peleg, O. (2002). Bowen theory: A study of differentiation of self and students’ social anxiety and physiological symptoms. Contemporary Family Therapy, 24, 355–369. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015355509866.

Peleg, O. (2008). The relation of differentiation of self and marital satisfaction: What can be learned from married people over the life course? The American Journal of Family Therapy, 36, 388–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180701804634.

Peleg, O. (2022). The relationship between type 2 diabetes, differentiation of self, and emotional distress: Jews and arabs in Israel. Nutrients, 14, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14010039.

Peleg, O., & Grandi, C. (2019). Family and anxiety: Are there differences between Israeli and Italian students? International Journal of Psychology, 54(6), 816–827. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12535.

Peleg, M., & Peleg, O. (2023). Personality and family risk factors for poor mental well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20, 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010839.

Peleg, O., Boniel-Nissim, M., & Tzischinsky, O. (2022). The mediating role of emotional distress in the relationship between differentiation of self and the risk of eating disorders among young adults. Clinical Psychiatry, 8(6). https://doi.org/10.35841/2471-9854-8.6.144.

Rasheed, N., Fatima, I., I., & Tariq, O. (2022). University students’ mental well-being during COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of resilience between meaning in life and mental well-being. Acta Psychologica, 227, 103618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103618.

Reevy, G. M., & Maslach, C. (2001). Use of social support: Gender and personality differences. Sex Roles, 44, 437–459. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011930128829.

Sadeghi, M., Barahmand, U., & Roshannia, S. (2020). Differentiation of self and hope mediated by resilience: Gender differences. Canadian Journal of Family & Youth, 11. https://doi.org/10.29173/cjfy29489.

Saltzman, L. Y., Hansel, T. C., & Bordnick, P. S. (2020). Loneliness, isolation, and social support factors in post-COVID-19 mental health. Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000703.

Sardella, A., Lenzo, V., Basile, G., Musetti, A., Franceschini, C., & Quattropani, M. C. (2022). Gender and psychosocial differences in psychological resilience among a community of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 12(9), 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12091414.

Skowron, E. A. (2004). Differentiation of self, personal adjustment, problem solving, and ethnic group belonging among persons of color. Journal of Counseling & Development, 82(4), 447–456. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2004.tb00333.x.

Skowron, E. A., & Friedlander, M. (1998). The differentiation of self inventory: Development and initial validation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 28, 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.45.3.235.

Skowron, E. A., & Schmitt, T. A. (2003). Assessing interpersonal fusion: Reliability and validity of a new DSI FWO subscale. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 29, 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01201.x.

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972.

Soliman, D., Frydenberg, E., Liang, R., & Deans, J. (2021). Enhancing empathy in preschoolers: A comparison of social and emotional learning approaches. Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 38(1), 64–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/20590776.2020.1839883.

Suchocka, L., Krajewska, E., & Pasek, M. (2020). The need for social support and the functioning of individuals in a health-limiting condition. Humanities and Social Sciences, 27(4), 155–164. https://doi.org/10.5114/amos.2020.100004.

Tang, C., & Zhao, L. (2024). Gender social norms and gender gap in math: Evidence and mechanisms. Applied Economics, 56(17), 2039–2057. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2023.2178631.

Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411 – 29. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.107.3.411. PMID: 10941275.

Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., Parkinson, J., Secker, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2007). The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5, 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-63.

Tindle, R., Hemi, A., & Moustafa, A. A. (2022). Social support, psychological flexibility and coping mediate the association between COVID-19 related stress exposure and psychological distress. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 8688. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12262-w.

Walker, S. A., Pinkus, R. T., Olderbak, S., & MacCann, C. (2023). People with higher relationship satisfaction use more humor, valuing, and receptive listening to regulate their partners’ emotions. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04432.

Walsh, F. (2017). Strengthening family resilience (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Wettstein, M., Nowossadeck, S., & Vogel, C. (2022). Well-being trajectories of middle-aged and older adults and the Corona pandemic: No COVID-19 effect on life satisfaction, but increase in depressive symptoms. Psychology & Aging, 37(2), 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000664.

Wright, M. O., Masten, A. S., & Narayan, A. J. (2013). Resilience processes in development: Four waves of research on positive adaptation in the context of adversity. In S. Goldstein & R. B. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 15–37). Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3661-4_2.

Yıldırım, M., & Arslan, G. (2022). Exploring the associations between resilience, dispositional hope, preventive behaviors, subjective well-being, and psychological health among adults during early stage of COVID-19. Current Psychology, 41(8), 5712–5722. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01177-2.

Yıldırım, M., & Belen, H. (2018). The role of resilience in the relationships between externality of happiness and subjective well-being and flourishing: A structural equation model approach. Journal of Positive Psychology & Wellbeing, 3(1), 62–76. https://www.journalppw.com/index.php/JPPW/article/view/85.

Zautra, A. J., Arewasikporn, A., & Davis, M. C. (2010). Resilience: Promoting well-being through recovery, sustainability, and growth. Research in Human Development, 7(3), 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2010.504431.

Zeka, B., & Alhassan, A. L. (2023). Gender disparities in financial resilience: Insights from South Africa. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 14, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1028754.

Zimet, G. D., Dahkem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1). https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Helene Hogri for her valuable contribution in editing the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Max Stern Academic College of Emek Yezreel.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Research involving human participants and/or animals

The research involves human participants.

Informed Consent

All participants provided their informed consent by signing a form, which was presented on the first page of the questionnaire.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peleg, O., Peleg, M. Is Resilience the Bridge Connecting Social and Family Factors to Mental Well-Being and Life Satisfaction?. Contemp Fam Ther (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-024-09707-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-024-09707-x