Abstract

Conversations about climate change are crucially important for mobilizing climate action, as well as for processing emotions and finding meaning in times of crisis. However, limited guidance exists on how to successfully facilitate these discussions, especially among individuals with a wide range of beliefs, knowledge levels, and opinions about climate change. Here, we describe the Talk Climate Change project — an Oxford University student-led climate conversation campaign associated with the 2021 United Nations COP26 meeting. Over 1000 individuals across 40 countries held climate-related discussions. They then described their discussions in submissions to an interactive conversation map (www.talkclimatechange.org), along with messages to COP26. We reflect on the campaign’s outcomes and offer advice on overcoming barriers to effective climate dialogue; how to handle emotional responses; and other considerations for catalyzing meaningful and productive climate discussions. We call for a stronger focus on training conversational skills, providing context-specific discussion resources, and empowering diverse people to have conversations about climate change among their families, friends, coworkers, and communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

“How many of our friends and family members understand why COP26 is important or what it even is?”

This is the question that we, a group of graduate students at the University of Oxford asked ourselves in January 2021. There was already much speculation about the potential outcomes of the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), to be held in November 2021 in Glasgow, Scotland. COP is the annual meeting of parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change during which delegates assess and negotiate paths for mitigating and adapting to climate change (Evans et al. 2021). The outcomes of these negotiations affect all life on Earth. At the time, we were struck by the limited awareness of it beyond individuals directly involved in environmental work. When we mentioned COP26 to close contacts not engaged in the environmental movement in professional or personal contexts, the term was unfamiliar to most of them. Even among our fellow students, in the same country as the upcoming conference, awareness was surprisingly low. Public polling confirmed this perception. In September and October 2021, only 35% of people in Great Britain reported knowing of COP26 and understanding what it was about; this figure was even lower in the USA, where only 14% of Americans reported an awareness and understanding of it (Hudson et al. 2021).

Fortunately, awareness of COP26 increased during the conference, such as in the UK, where 60% of the public reported hearing a fair or significant amount about COP26 in November 2021 (Conner 2021). This was most likely associated with substantial media coverage of the conference (Boykoff et al. 2022). Nevertheless, that such a pivotal meeting could remain a matter relatively confined to the environmental community is not only troubling — it is also risky. Public engagement is crucial for climate action, especially as many decarbonization and adaptation solutions require public participation to ensure their success (Hügel & Davies 2020). For example, transitioning energy systems away from fossil fuels, such as through the construction of renewable energy infrastructure, can encounter significant opposition without community buy-in and support (Perlaviciute et al. 2018). A report commissioned by the UK’s Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy notes that effective public engagement is essential for successfully achieving net zero targets (Demski 2021). Likewise, public opinion and voting preferences can influence policy agendas (Brulle et al. 2012). A lack of awareness can also reduce the diversity of voices on the issue, allowing fossil fuel corporations and high polluting industries to dominate (Global Witness 2021), while excluding vulnerable and marginalized communities most susceptible to climate impacts (Sultana 2022).

We therefore decided to use COP26 as an opportunity to start a student-led conversation campaign to help broaden the range of individuals aware of and engaged in climate action. Our campaign (www.talkclimatechange.org) sought to inspire and track 26,000 climate conversations worldwide from June 2021 to November 2021. In this essay, we discuss our experiences designing the campaign and reflect on the lessons its outcomes hold for climate change communication.

2 Deficit versus dialogue

At first, we contemplated creating an informational website to educate others about COP26 and climate change more generally. This is the most common mode of science communication — known as the deficit model, one provides information and presumably it fills gaps in another’s understanding (Sturgis & Allum 2004). To be sure, it is vitally important that the scientific community continue to inform the public about advances in research and understanding. Nevertheless, researchers have for decades pointed out limitations of the deficit model, as it implies that attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors are based solely on knowledge, rather than a complex array of personal, contextual, cultural, and value-driven factors (Simis et al. 2016). It also tends to treat the public as a single entity when it is in fact composed of diverse groups and individuals.

As we sought to not only inform people beyond the environmental community about the conference but also find a way to feed their views and perspectives back to COP, we required a different approach. We also wanted to empower a diverse range of individuals — both including and beyond scientists — to start conversations. We therefore decided to follow a public engagement approach, also known as the dialogue model (Suldovsky 2017). In contrast to the deficit model, the dialogue model does not view communication as a one-way transfer of knowledge from expert to lay person. Instead, it seeks to break down divisions between technical and public spheres to facilitate spaces for the exchange of ideas, opinions, and information; at a practical level, this may entail interpersonal discussions and other public engagement opportunities that incorporate two-way communications (Wibeck 2014; Patenaude & Bloomfield 2022).

Researchers are increasingly recognizing that dialogue-driven approaches are vital for climate action. Conversations about climate change provide opportunities for reflection on the issue’s many different impacts, meanings, and emotional responses (Salamon & Gage 2020; Tait et al. 2022). For instance, studies have documented the effectiveness of climate community forums and citizen assemblies for public engagement (e.g., Devaney et al. 2020; Hanson 2018; Myers et al. 2017). During these sessions, citizens are typically exposed to climate science, but also offered the opportunity to engage in discussions and deliberation about the material. Furthermore, conversations hold communicative power. Goldberg et al. (2019) found that discussions among family and friends helped improve understanding of the scientific consensus that climate change is occurring and driven by human activities. On social media, some scientists have found conversational approaches, rather than didactic teaching, to be a more rewarding form of engagement about climate change (Hawkins et al. 2014). Conversational approaches can also help reach individuals less exposed to climate information and media coverage, such as in rural communities with limited Internet access (Mycoo 2015).

Despite the importance and effectiveness of climate conversations, such discussions among the public do not often happen. In the USA, in contrast to growing alarm about climate change, about 2/3 of Americans say they rarely or never talk about climate change (Leiserowitz et al. 2021). Some researchers have called this the climate spiral of silence (Maibach et al. 2016). According to the spiral of silence theory, individuals are less willing to express opinions that they believe are not shared by others, which in turn influences public opinion (Noelle-Neumann 1993). A spiral is a fitting metaphor for this silencing effect, as the less people hear others speak about climate change, the less they feel it is a socially acceptable topic for discussion, creating a vicious cycle. Researchers have found that those who care about climate change underestimate how much others care about it, which leads to self-silencing on the issue (Geiger & Swim 2016). A misunderstanding of how others feel about an issue is known as pluralistic ignorance, which is a common phenomenon for climate change (Sparkman et al. 2022). The notion of individual silence associated with a lack of social support is pertinent to a variety of societal issues, such as in the context of sexual violence and the #MeToo movement (Zacharek et al. 2017). Discussing climate change can also feel uncomfortable as it is a politically charged topic, which is, in part, a result of decades of campaigns by fossil fuel companies to sow doubt, division, and mistrust about the issue (Supran & Oreskes 2021).

Power dynamics are an additional consideration. As Bucchi and Trench (2021, p.7) note, conversations are “. . . not necessarily open and equitable. Many attributes can be a handicap to participation, including gender, educational level, ethnicity, and language. It takes conscious action to address these imbalances and exclusions.” This is particularly relevant to climate change as the environmental movement has been criticized for excluding women, people of color, Indigenous peoples, and poorer populations in the Global South who are not only the most vulnerable to climate change, but often least heard when it comes to climate decision-making (Okereke & Coventry 2016; Abimbola et al. 2021). Furthermore, climate change can be unpleasant, distressing, and awkward to discuss, especially amid significant political polarization and climate anxiety (Hickman et al. 2021). One may also feel unprepared to engage in climate change discussions due to a perceived lack of knowledge on the topic (Geiger et al. 2017). However, researchers have shown that climate change communication training can increase the frequency and quality of climate discussions (Swim et al. 2018).

Compared to the large number of studies incorporating a one-way climate communication model, there is limited evidence-based guidance on strategies for successfully encouraging climate conversations (Markowitz & Guckian 2018). There is growing empirical evidence that having climate conversation participants identify shared values (i.e., objects or ideals that individuals feel are worth protecting) can support positive conversational outcomes (Bloomfield et al. 2020). For example, van Swol et al. (2022) found that facilitating group discussions based on shared values was more effective toward building group consensus on climate change beliefs than discussions based purely around a climate change article. Establishing shared values has also been found to increase support for climate policies (Geiger et al. 2022). Drawing on her personal experiences and empirical literature, climate scientist Dr. Katharine Hayhoe advises finding ways to connect climate change to specific interests and values among diverse communities, e.g., among faith groups, talking about religious values of protecting living beings; among wine connoisseurs, how climate change impacts vineyards; among scuba divers, the impacts of warming oceans; etc. (Hayhoe 2021).

An analysis of the 2019 Curious Climate Tasmania project, which sought to facilitate climate conversations between scientists and non-scientists, highlights the importance of establishing trust, agency to act, and a genuine back and forth exchange (Kelly et al. 2020). Likewise, the organization Climate Outreach advises establishing respect, asking questions, and practicing active listening to ensure a civil and effective discussion (Webster & Marshall 2019). Other organizations have trained youth to engage their parents about climate change, drawing upon motivational interviewing techniques, such as asking open-ended questions to encourage storytelling (ACE 2017). We incorporated these guidelines into our campaign strategy and build on them below.

3 The Talk Climate Change campaign

We launched the campaign in June 2021 and set a goal of encouraging and documenting 26,000 climate conversations by 1 November 2021 — the first day of COP26. The number 26,000 was a relatively arbitrary decision; we chose a number loosely related to COP26 that was ambitious and attention-grabbing, but not impossible to achieve. The conversations did not have to relate to COP26, but we used the occasion of the conference as a call to action. Conversations could be held over any medium, in person or online, so long as there was a back-and-forth dialogue. We built an associated website to serve as the platform for our campaign. The core structure of the website included a form in which anyone could submit information about their climate conversations and an interactive map showcasing climate conversations submitted from around the world (see www.talkclimatechange.org). Although we expected our participants to consist mostly of environmentally concerned individuals, we encouraged them to have conversations with others beyond the environmental community to help break the spiral of silence. We hoped that this would initiate opportunities for diverse individuals who do not frequently speak about climate change to understand, reflect upon, and find ways to support climate action. Engaging in these discussions (as well as viewing the resulting conversation map) could help counter perceptions of pluralistic ignorance by showing that people care about — and are talking about — the issue more than often assumed (Geiger & Swim 2016).

When deciding what and how much information to collect via the form, we did not want to make the process of filling out the form too arduous. We also needed to balance considerations of privacy, cybersecurity, and anonymity. Accordingly, we required submissions to include the first name of the person submitting, the first name of their conversation partner, their relationship, the location where the conversation took place (no more specific than city/town), the conversation content, and up to five pre-populated thematic tags describing the discussion content (e.g., “food” and “transport”). We offered participants an open-ended space to describe their conversations and the meaning they derived from them, as well as the option to write a message to COP26 (which we later presented at the conference) and to upload an image associated with the conversation. Initially, we allowed images of the participants or of objects or landscapes representative of the conversation topic; however, we ultimately deleted all images containing people from the dataset to provide full participant anonymity. For additional safety for minors, when submitters clicked a box that they were under 18 years old, the photo upload feature was disabled. As this article describes a non-identifiable dataset created prior to the conception of this publication, it was exempt from ethical approval in accordance with the University of Oxford's Central University Research Ethics Committee guidelines.

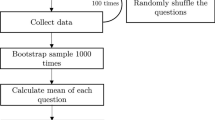

Figure 1 shows an example of a conversation submission. We also developed brief conversation prompts on a range of topics such as climate justice, nature-based solutions, and net zero, as well as a guide for educators to use in the classroom. The educator guide adapted general climate conversation guidance to the more structured environment of the classroom, including advice from a sustainability education expert, lesson plans, and a worksheet. Likewise, we collected brief conversation advice statements from 50 leading environmental scholars and activists from diverse backgrounds (e.g., age, expertise, gender, and race). These statements offer valuable expert perspectives on both the importance of climate conversations and practical strategies for facilitating effective discussions. We promoted the campaign on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Twitter, as well as via relevant external email newsletters. We also created a 1-min promotional video which introduced the campaign and provided instructions on how to participate. The conversation map, expert advice statements, guides, promotional video, and other materials remain available at www.talkclimatechange.org.

4 Campaign outcomes

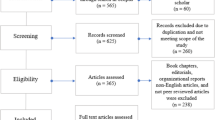

We received a total of about 500 climate conversation submissions, involving over 1,000 people, from 40 countries. The conversations took place among people with many kinds of relationships, including children, siblings, parents, grandparents, friends, co-workers, taxi drivers, nurses, strangers, and more. Conversations covered a wide range of topics (Table 1). We note that as self-reported data, the submissions represent how campaign participants perceived and reflected upon their discussions, rather than being necessarily complete, objective, or accurate accounts.

Numerous conversation submissions indicated plans to pursue further individual climate actions post-discussion, such as reducing personal energy use, engaging in activism, and more regularly having discussions. For instance:

My friend and I talked about how to support environmental and climate objectives through professional careers that are not specifically focused on these issues. We discussed the personal and ethical debates surrounding choice of profession/vocation and the trade-offs of working directly for a climate-focused org with those of working for a large company not focused on climate but with substantial potential to support climate goals. . . We didn't make any decisions related to our own careers, but we did decide to continue these important conversations in the months and years ahead.

Messages to COP26 expressed a wide range of sentiments. The most common messages urged countries to increase the ambition of their emissions reduction targets, diversify climate leaders and voices represented at the conference, and generally take the threat of climate change more seriously. For example:

Our message to COP26 is that we want desperately to show world governments and industry leaders that the world can be saved and that it's not hopeless, but we have to act now. Individual change can only do so much because so much is based on a global industrial scale. I want my sister to grow up in a world where she can still thrive.

Our website received over 15,000 visits from over 120 countries and a high level of engagement on social media (e.g., over 100,000 Twitter impressions on our campaign launch announcement alone and 25,000 views of our campaign video). This suggests that there was significant interest in learning more about our campaign, as well as in viewing conversations submitted by others (regardless of whether these visitors ultimately participated). The campaign was also featured in a WIRED Magazine article on ways to act on climate change (WIRED 2021). We made special efforts to elevate submissions from Global South countries by, for instance, highlighting them in our email newsletters and social media posts. We organized a range of climate conversation events, including running a climate conversation activity for children and their families during the London Science Museum’s “Future Explorers” program, participating in the UK’s “Great Big Green Week,” and holding workshops among community and interfaith groups where we trained participants to have effective climate conversations. We also worked to engage students, faculty, and staff across our university. The project was presented at COP26 as part of a Paris Committee on Capacity Building panel and other outreach activities during the conference.

5 Lessons for climate change communication

Based on our experiences conducting the campaign and upon subsequent reflection on its outcomes, we offer five lessons for effectively facilitating climate conversations among individuals with differing beliefs, opinions, and knowledge levels about climate change. These suggestions build on the prior literature described above and are intended for environmental communication practitioners seeking to increase both the quantity and quality of climate conversations in diverse settings.

5.1 Affirm the importance of climate conversations

The submissions to our interactive map from 40 countries exhibit a remarkably meaningful and rich array of climate conversations, covering a diversity of topics discussed by people with varying relationships. Numerous submissions mentioned plans to build on initial discussions to incorporate other ways of taking action on climate change. Yet while the quality of participation was excellent, we fell far short of our goal of 26,000 submissions. As described, this stands in contrast to the significant online engagement we received both in visits to our website and engagement on social media from around the world. This disparity suggests that many people were interested in the campaign but ultimately did not participate. This is not entirely surprising; catalyzing climate conversations can be difficult, which is, after all, why we started the campaign in the first place. Research in the USA shows that even among those most alarmed about climate change, only about a third participate in climate activism (Goldberg et al. 2021). The total number of submissions may also reflect the limited resources of a student project conducted on a volunteer basis, as well as the short time window of the campaign.

Speaking up about a topic as unsettling as climate change is not easy — it takes courage. Therefore, encouraging climate conversations is, in part, a matter of incentives. Participants need to be reminded of the importance of these conversations for inspiring both individual behavior change and climate activism targeted at policymakers and other stakeholders, as well as for providing opportunities for dialogue on this enormous societal issue. Although a single discussion may not immediately lead to dramatic impacts, at scale thousands of discussions hold immense power. Furthermore, many individuals ultimately find these discussions rewarding, even if they can feel somewhat awkward to start. As one participant described:

A number of practical actions emerged [from the conversation], which were previously unclear. I left the meeting feeling much more able to make a positive difference through my everyday words and actions.

Likewise, in order to fight feelings of pluralistic ignorance and alienation (Geiger & Swim 2016), campaign organizers should make participants feel part of a larger conversation effort. Tracking conversations, as we did on our interactive map, is one way of achieving this; on the other hand, the time and effort required to submit a conversation summary adds an additional barrier to participation. This is likely another factor for why we did not receive as many submissions as hoped. Structured venues and events, such as Climate Cafés (Tait et al. 2022), can also help facilitate climate discussions.

5.2 Build conversational skills

Based on anecdotal feedback, we realized that another barrier to participation was a feeling of discomfort and lack of preparation for engaging in climate conversations, reflecting the aforementioned empirical findings on climate discussions (e.g., Geiger et al. 2017). We therefore began conducting climate conversation workshops in which we explained barriers to effective environmental communication, explored potential conversation topics, described how to handle emotional responses, and practiced listening skills. This included an active listening exercise sometimes taught in mindfulness courses in which participants listen to someone else speak for several minutes and are not permitted to respond verbally (body language reactions are allowed). They then switch roles to experience what it feels like to truly be heard. As Oxford University economist Kate Raworth noted in her submission of conversation advice to our website:

If you begin with curiosity, empathy and genuine listening, you’ll find that a topic that once seemed so hard to crack open can suddenly turn into a lively discussion that flows towards action.

These training sessions proved helpful as participants reported feeling more comfortable with the prospect of engaging in climate discussions.

Like any other communication technique, interpersonal dialogue is a skill that can always be improved. Further evidence-based guidance for having effective climate conversations and training associated skills would be beneficial. A foundational understanding of scientific, social, and policy aspects of climate change can also build one’s confidence to engage in discussions on the topic.

5.3 Tailor the conversation

Among the skills we taught in our conversation workshops, a helpful technique is considering the background, beliefs, interests, and values of one’s conversation partner and framing the discussion accordingly (Swim et al. 2018; Hayhoe 2021). In practice, this means asking pertinent questions to explore what others care about and seeking to link these interests to climate action. This approach helps facilitate more personally meaningful and relevant discussions. The most frequent thematic tags listed above (Table 1) reflect how campaign participants sought to make their discussions relevant to their conversation partners’ lives by discussing their personal carbon footprints, social dimensions of climate change, and local weather. For instance, one participant tailored a discussion based on his conversation partner’s political views:

I talked to a conservative family member about their concerns about the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act and helped them feel better about measures being taken to preserve the US’s economy while environmental regulations are put in place. I hope this opened the door for future conversations with my conservative family members about the climate.

Others used extreme weather events as a basis for discussions:

After an unprecedented heatwave, it’s easy to start this kind of conversation.

Tailoring a conversation requires careful listening, authenticity, and trust. Tailoring can be conducted transparently, rather than in a manipulative manner; communicators can openly explain that they would like to explore how climate change is relevant to their conversation partner's interests, rather than attempting to do so covertly.

5.4 Give space for diverse emotional responses

Climate change can evoke a wide range of emotions with varying levels of intensity (Brosch 2021). For many, it may evoke strongly negative feelings such as anger, fear, guilt, and worry (Hickman et al. 2021), as well as feelings of uncertainty (Moser 2014). It is important to affirm the validity of different kinds of emotional responses to climate change and acknowledge that there is no single appropriate way to feel about the issue. Climate conversationalists should therefore provide a safe space for individuals to express how they truly feel without fear of judgment or retribution. As Dr. Britt Wray, Stanford University, explained in a contribution to our campaign:

To meet this distress, we need to have socially supportive conversations with others who can legitimize these concerns, reckon with feelings rather than dismiss them, and provide the creative environment in which people can strategize about how they’re going to show up in the world, as individuals and collectives, to meet the moment.

Communicators should not view conversations as a debate to be won; rather, they should see them as an opportunity for mutual learning. On a more practical level, we also encouraged our campaign participants to check that their conversation partners were comfortable discussing the topic and explain that they could end the discussion at any time. Likewise, environmental communicators are not obliged to remain in conversations with individuals who do not reciprocate kindness and respect.

5.5 Provide resources for distinct conversational settings

To successfully facilitate climate conversations, one must consider among whom discussions occur, in what venues they take place, and to what extent individuals feel empowered to participate. Different locales, such as businesses, classrooms, and community centers, can benefit from specially tailored conversation resources and training suited to their needs and context. As a teacher from Islamabad, Pakistan, described in her submission:

As a class we talked about how climate change is the most pressing environmental issue we are faced with today . . . We hope to spread our knowledge about climate change with our school community soon and start a discussion on how we as a school community can help take action.

Different resources are clearly needed to support a teacher engaging her class (e.g., by providing climate action activities relevant and accessible to students), compared to conversations among companies, governments, communities, and other contexts.

One of the most memorable experiences of our campaign was running a climate conversations activity booth at the London Science Museum for children and their families. We prepared a set of conversation prompts about climate change designed for children, such as their feelings about being in nature, protecting animals, and sustainability in their schools. We guided parents and guardians to have these conversations for about 10–15 min, with their children subsequently filling out a worksheet describing their discussion (Fig. 2). It also proved a useful opportunity to educate families about COP26, and many wrote messages to the conference. We estimate that a total of about 450 children and their parents/guardians participated in climate conversations at the museum. We were surprised by the number of people who told us it was the first conversation they ever had with their children about climate change. Many of them found it to be an emotionally moving experience.

6 Conclusion

This article has described our experiences designing and conducting a climate conversations campaign in the lead-up to COP26. We hope our campaign’s successes and challenges serve as a useful model for environmental advocates pursuing similar dialogue-driven approaches for public engagement. In the near future, we plan to offer our conversational map as a free online tool for environmental groups to encourage discussions about climate change and related issues as part of their campaigning efforts. Like any communication technique, conversational skills can always be improved, especially when grappling with sensitive, emotionally charged issues. More resources and training opportunities should be made available to help environmental practitioners, researchers, and advocates facilitate effective interpersonal dialogue in diverse settings. Amid significant political polarization, conversations about climate change can help break down barriers and echo chambers, opening new possibilities for cooperation and progress. Furthermore, climate conversations can also help elevate voices less often heard and offer new ideas and solutions. As Dr. Anthony Leiserowitz, Director of the Yale University Program on Climate Change Communication, explained in a contribution to our campaign:

Climate change can seem overwhelming, but each of us has this superpower - of talking with and engaging the people we love, who talk to other people, who talk to other people, who talk to other people, until everyone is talking about it, which changes public and political will for climate action. And it all starts with a simple conversation!

Our campaign was born out of the simple idea to use the power of dialogue to engage people about the complex and often emotionally charged issue of climate change. By encouraging participants to listen, learn, and approach climate conversations openly and empathetically, we successfully empowered diverse individuals to speak up about climate change in their local communities. This helps fight the climate spiral of silence. Ultimately, we hope this model can help support a ground-up increase in political and social action on climate change and other pressing societal challenges.

Data availability

Further details about the student initiative that forms the basis of this publication are available at www.talkclimatechange.org.

References

Abimbola O, Kwesi Aikins J, Makhesi-Wilkinson T, Roberts E (2021) Racism and climate (In) Justice. How racism and colonialism shape the climate crisis and climate action. Washington, DC: Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung Washington, DC.

ACE (2017) The power of conversation: training youth to lead climate conversations with parents. https://acespace.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/The-Power-of-Conversation_-ACE-Climate-Conversations-Executive-Summary.pdf. Accessed 8 Apr 2022

Bloomfield EF, Van Swol LM, Chang C-T, Willes S, Ahn PH (2020) The effects of establishing intimacy and consubstantiality on group discussions about climate change solutions. Sci Commun 42(3):369-394. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547020927017

Boykoff M, Katzung J, Nacu-Schmidt A, Pearman O (2022) A review of media coverage of climate change and global warming in 2021 [online]. Media and Climate Change Observatory, Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado. http://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/icecaps/research/media_coverage/summaries/special_issue_2021.html. Accessed 6 Sept 2022

Brosch T (2021) Affect and emotions as drivers of climate change perception and action: a review. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, Human Response to Climate Change: From Neurons to Collective Action 42:15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.02.001

Brulle RJ, Carmichael J, Jenkins JC (2012) Shifting public opinion on climate change: an empirical assessment of factors influencing concern over climate change in the U.S., 2002–2010. Climatic Change 114:169–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-012-0403-y

Bucchi M, Trench B (2021) Rethinking science communication as the social conversation around science. JCOM 20, Y01. https://doi.org/10.22323/2.20030401

Conner J (2021) What impact did COP26 have on public opinion? [online]. YouGov. https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2021/11/22/what-impact-did-cop26-have-public-opinion. Accessed 6 Sept 2022

Demski C (2021) Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/969428/net-zero-public-engagement-participation-research-note.pdf. Accessed 7 Apr2022

Devaney L, Torney D, Brereton P, Coleman M (2020) Ireland’s citizens’ assembly on climate change: lessons for deliberative public engagement and communication. Environ Commun 14:141–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2019.1708429

Evans S, Gabbatiss J, McSweeney R, Chandrasekhar A, Tandon A, Viglione G, Hausfather Z, You X, Goodman J, Hayes S (2021) COP26: key outcomes agreed at the UN climate talks in Glasgow [online]. Carbon Brief. https://www.carbonbrief.org/cop26-key-outcomes-agreed-at-the-un-climate-talks-in-glasgow/. Accessed 17 Sept 2022

Geiger N, Sarge MA, Comfort RN (2022) An examination of expertise, caring, and salient value similarity as source factors that garner support for advocated climate policies. Environ Commun. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2022.2080242

Geiger N, Swim JK (2016) Climate of silence: pluralistic ignorance as a barrier to climate change discussion. J Environ Psych 47:79–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.05.002

Geiger N, Swim JK, Fraser J (2017) Creating a climate for change: interventions, efficacy and public discussion about climate change. J Environ Psych 51:104–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.03.010

Global Witness (2021) Hundreds of fossil fuel lobbyists flooding COP26 climate talks (online). https://www.globalwitness.org/en/press-releases/hundreds-fossil-fuel-lobbyists-flooding-cop26-climate-talks/. Accessed 16 Sept 2022

Goldberg M, Wang X, Marlon J, Carman J, Lacroix K, Kotcher J, Rosenthal S, Maibach E, Leiserowitz A (2021) Segmenting the climate change alarmed: active, willing, and inactive. Yale University and George Mason University. New Haven, CT: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication

Goldberg MH, van der Linden S, Maibach E, Leiserowitz A (2019) Discussing global warming leads to greater acceptance of climate science. PNAS 116:14804–14805. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1906589116

Hanson LL (2018) Public deliberation on climate change: lessons from Alberta Climate Dialogue. Athabasca University Press.

Hawkins E, Edwards T, McNeall D (2014) Pause for thought. Nature. Clim Change 4:154–156. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2150

Hayhoe K (2021) Saving us: a climate scientist’s case for hope and healing in a divided world. Simon and Schuster

Hickman C, Marks E, Pihkala P, Clayton S, Lewandowski RE, Mayall EE, Wray B, Mellor C, van Susteren L (2021) Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey. The Lancet Planetary Health 5:e863–e873. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3

Hudson J, Morini P, Hudson D (2021) Public attitudes towards climate & COP-26: views from France, Germany, Great Britain, and the U.S. [Online]. Development Engagement Lab. https://www.developmentcompass.org/storage/del-cop26-and-climate-20211026-final-1-1635696422.pdf. Accessed 8 Feb 2023

Hügel, S., Davies, A.R., 2020. Public participation, engagement, and climate change adaptation: a review of the research literature. WIREs Climate Change 11, e645. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.645

Kelly R, Nettlefold J, Mossop D, Bettiol S, Corney S, Cullen-Knox C, Fleming A, Leith P, Melbourne-Thomas J, Ogier E, van Putten I, Pecl GT (2020) Let’s talk about climate change: developing effective conversations between scientists and communities. One Earth 3:415–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.09.009

Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Rosenthal S, Kotcher J, Carman J, Neyens L, Marlon J, Lacroix K, Goldberg M (2021) Climate change in the American mind, September 2021. Yale University and George Mason University. New Haven, CT: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication

Maibach E, Leiserowitz A, Rosenthal S, Roser-Renouf C, Cutler M (2016) Is there a climate “spiral of silence” in America?. Yale University and George Mason University. New Haven, CT: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication

Markowitz EM, Guckian ML (2018) Climate change communication: challenges, insights, and opportunities, in: Clayton, S., Manning, C. (Eds.), Psychology and Climate Change. Academic Press, pp. 35–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813130-5.00003-5

Moser SC (2014) Communicating adaptation to climate change: the art and science of public engagement when climate change comes home. WIREs Climate Change 5:337–358. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.276

Mycoo M (2015) Communicating climate change in rural coastal communities. Int J Clim Change Strat Manag 7:58–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-04-2013-0042

Myers CD, Ritter T, Rockway A (2017) Community deliberation to build local capacity for climate change adaptation: the Rural Climate Dialogues Program, in: Leal Filho, W., Keenan, J.M. (Eds.), Climate change adaptation in North America: fostering resilience and the regional capacity to adapt, climate change management. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-53742-9_2

Noelle-Neumann E (1993) The spiral of silence: public opinion–our social skin. University of Chicago Press

Okereke C, Coventry P (2016) Climate justice and the international regime: before, during, and after Paris. WIREs Climate Change 7:834–851. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.419

Otto IM, Donges JF, Cremades R, Bhowmik A, Hewitt RJ, Lucht W, Rockström J, Allerberger F, McCaffrey M, Doe SSP, Lenferna A, Morán N, van Vuuren DP, Schellnhuber HJ (2020) Social tipping dynamics for stabilizing Earth’s climate by 2050. PNAS 117:2354–2365. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1900577117

Patenaude HK, Bloomfield EF (2022) Topical analysis of nuclear experts’ perceptions of publics, nuclear energy, and sustainable futures. Front Commun 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2022.762101

Perlaviciute G, Schuitema G, Devine-Wright P, Ram B (2018) At the heart of a sustainable energy transition: the public acceptability of energy projects. IEEE Power and Energy Magazine 16:49–55. https://doi.org/10.1109/MPE.2017.2759918

Salamon MK, Gage M (2020) Facing the climate emergency: how to transform yourself with climate truth. New Society Publishers.

Simis MJ, Madden H, Cacciatore MA, Yeo SK (2016) The lure of rationality: why does the deficit model persist in science communication? Public Underst Sci 25:400–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662516629749

Sparkman G, Geiger N, Weber EU (2022) Americans experience a false social reality by underestimating popular climate policy support by nearly half. Nat Commun 13:4779. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32412-y

Sturgis P, Allum N (2004) Science in society: re-evaluating the deficit model of public attitudes. Public Underst Sci 13:55–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662504042690

Suldovsky B (2017) The information deficit model and climate change communication. Oxford Res Encyclopedia of Clim Sci. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.013.301

Sultana F (2022) The unbearable heaviness of climate coloniality. Political Geography 102638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102638

Supran G, Oreskes N (2021) Rhetoric and frame analysis of ExxonMobil’s climate change communications. One Earth 4:696–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.04.014

Swim JK, Geiger N, Sweetland J, Fraser J (2018) Social construction of scientifically grounded climate change discussions. In: Clayton S, Manning C (eds) Psychology and climate change: from denial and depression to adaptation and resilience. Elsevier, pp 65–93

Tait A, O’Gorman J, Nestor R, Anderson J (2022) Understanding and responding to the climate and ecological emergency: the role of the psychotherapist. British J Psychotherapy. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjp.12776

van Swol LM, Bloomfield EF, Chang C-T, Willes S (2022) Fostering climate change consensus: the role of intimacy in group discussions. Public Underst Sci 31:103–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625211020661

Webster R, Marshall G (2019) The #TalkingClimate handbook: how to have conservations about climate change in your daily life. Climate Outreach. https://climateoutreach.org/reports/how-to-have-a-climate-change-conversation-talking-climate/. Accessed 17 Sept 2022

Wibeck V (2014) Enhancing learning, communication and public engagement about climate change - some lessons from recent literature. Environ Educ Res 20(3):387–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.812720

WIRED (2021) Actions you can take to tackle climate change. https://www.wired.com/story/actions-you-can-take-to-tackle-climate-change/amp. Accessed 7 Apr2022

Zacharek S, Dockterman E, Edwards HS (2017) “TIME person of the year 2017: the silence breakers.” TIME. http://time.com/time-person-of-the-year-2017-silence-breakers. Accessed 7 Sept 2022

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the many people across our university and around the world who participated in our conversation campaign and supported us in other ways, including providing guidance and resources, testing the web platform, and promoting the project among personal networks and communities. We specifically thank Jory Fleming, Macarena Carmona Schwartzmann, Ben Harwood, Melissa Bradshaw, Jill Kubit, Deb Morrison, Gary Belkin, Alice Chautard, Erica Nielsen, Oxford University Environmental Change and Management alumni, and the 50 climate experts who provided conversation advice statements for our website. Lastly, we express our thanks to three anonymous reviewers whose feedback significantly strengthened this paper.

Funding

The campaign described in this article was supported by funding from the following sources:

1. University of Oxford, Van Houten Fund

2. University of Oxford, Environmental Change Institute

3. University of Oxford, Oxford Climate Society

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JE: conceptualization, project administration, writing – original draft and editing

AM: conceptualization, manuscript review and editing, project administration

MPS: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, manuscript review and editing, project administration

BK, ZS, WF: project support, manuscript review and editing

AC: campaign website design and technical support

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

As this article is based on a non-identifiable dataset created prior to the conception of this publication, it was exempt from ethical approval in accordance with University of Oxford Central University Research Ethics Committee guidelines.

Consent to participate

Participants in the campaign gave their consent to submit their climate conversations to the campaign website.

Consent for publication

The campaign participants gave their consent for their climate conversations to be published.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ettinger, J., McGivern, A., Spiegel, M.P. et al. Breaking the climate spiral of silence: lessons from a COP26 climate conversations campaign. Climatic Change 176, 22 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-023-03493-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-023-03493-5