Abstract

We synthesized an expert review of climate change implications for hydroecological and terrestrial ecological systems in the northern coastal temperate rainforest of North America. Our synthesis is based on an analysis of projected temperature, precipitation, and snowfall stratified by eight biogeoclimatic provinces and three vegetation zones. Five IPCC CMIP5 global climate models (GCMs) and two representative concentration pathways (RCPs) are the basis for projections of mean annual temperature increasing from a current average (1961–1990) of 3.2 °C to 4.9–6.9 °C (5 GCM range; RCP4.5 scenario) or 6.4–8.7 °C (RCP8.5), mean annual precipitation increasing from 3130 mm to 3210–3400 mm (3–9 % increase) or 3320–3690 mm (6–18 % increase), and total precipitation as snow decreasing from 1200 mm to 940–720 mm (22–40 % decrease) or 720–500 mm (40–58 % decrease) by the 2080s (2071–2100; 30-year normal period). These projected changes are anticipated to result in a cascade of ecosystem-level effects including: increased frequency of flooding and rain-on-snow events; an elevated snowline and reduced snowpack; changes in the timing and magnitude of stream flow, freshwater thermal regimes, and riverine nutrient exports; shrinking alpine habitats; altitudinal and latitudinal expansion of lowland and subalpine forest types; shifts in suitable habitat boundaries for vegetation and wildlife communities; adverse effects on species with rare ecological niches or limited dispersibility; and shifts in anadromous salmon distribution and productivity. Our collaborative synthesis of potential impacts highlights the coupling of social and ecological systems that characterize the region as well as a number of major information gaps to help guide assessments of future conditions and adaptive capacity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

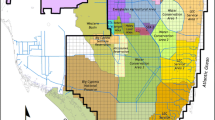

The northern coastal temperate rainforest of southeastern Alaska and British Columbia is the largest contiguous coastal temperate rainforest in the world, and yet there is limited synthesized information on transboundary climate change implications (Fig. 1). Steep, sloping watersheds where average winter temperatures are within a few degrees of freezing (Simpson et al. 2005), drain the Coast Range into estuaries of the eastern Pacific Ocean. This sharp environmental gradient results in a high degree of climatic sensitivity and changes in ecological communities over relatively short distances, our understanding of which would benefit from increased interdisciplinary collaboration. This paper represents the synthesis efforts of 15 regional resource experts to identify important social and ecological implications in the context of a long-term climate modeling exercise.

The governing watershed dynamics in this ecoregion can be grouped into three general categories: glacial melt, snowmelt, or rainfall systems (Edwards et al. 2013; Fig. 2). In lowland forest streams, the annual pattern of watershed discharge tracks the annual pattern of precipitation. These watersheds are predominantly found on island provinces (sections 2, 4, 5, and 6 in Fig. 1). Snowmelt watersheds are characterized by a spring snowmelt peak, a summer discharge minimum and an autumnal flow peak. These watersheds can be found on central parts of mountainous islands and in mainland provinces (1, 3, 7, and 8). Finally, high-elevation glacial watersheds export little water during winter and early spring, and have their main peak discharge during late spring to early fall. Glacial watersheds are found almost exclusively in mainland provinces (1, 3, and 8). Within this framework, a primary control on the timing and magnitude of stream flow is the proportion of the watershed that lies above the rain-snow transition zone, making the hydrology of this region particularly sensitive to changes in snowline elevation. For instance, water temperatures in rainfall dominated watersheds are 5–12 °C warmer during summer than snowmelt and glacial watersheds (Fellman et al. 2014).

Characteristic hydrographs for the three watershed types (glacial, snowmelt-dominated, and rain-dominated) in the coastal temperate rainforest of southeast Alaska and northern coastal British Columbia. Hydrographs are long term averages (30–60 years) from three individual representative streams in southeast Alaska, and are compared with long-term average precipitation in Juneau, Alaska, USA

Although species diversity is low relative to other rainforests globally, ecosystem productivity is extraordinarily high (Alaback 1996). For example, the total carbon stock in the forest and soils of the Tongass National Forest in southeast Alaska is 8 % of that in the conterminous United States (Leighty et al. 2006). Southeast Alaska (Halupka et al. 2003) and northern British Columbia (Temple 2005) contain a combined estimate of 7700 anadromous salmon streams with six Pacific salmonids (Oncorhynchus spp.). In southeast Alaska, salmon support an annual commercial and sport fisheries harvest of 30–70 million fish per year with a value estimated at $600 million to $1 billion (Waters 2010). Species distributions are consistent with island biogeography theory with a wide range of genetically isolated species or sub-species (Cook and MacDonald 2013). Rural human communities (approximately 50 % of the region’s population) are isolated by waterways and steep terrain, and rely on ferry, barge, and plane services for transportation. These communities rely on ecosystem services related to fish, wildlife, forests, water and scenery (Beier et al. 2008b; Crone and Mehrkens 2013; Patterson and Coelho 2009).

We synthesized an expert review of climate change implications for this region based on an analysis of projected temperature, precipitation, and snowfall. Each author was provided with a series of maps for each climate variable including the raw data from which to draw inferences. Implications for two general biophysical systems were considered—hydroecological (freshwater hydrology and fishes) and terrestrial ecological (vegetation and wildlife), and concluded with their associated ecosystem services. Five IPCC CMIP5 global climate models (GCMs) that performed well for the North Pacific were analyzed (Walsh et al. 2008; Radic and Clarke 2011): CCSM4, GFDL-CM3, GISS-E2-H, IPSL-CM5B-LR, and MRI-CGCM3. These were run for two representative concentration pathways (RCPs): RCP4.5 assumes medium-low global anthropogenic emissions and RCP8.5 assumes high emissions. The spatial climate modeling software ClimateWNA 4.85 (Wang et al. 2012b) and GIS were used to conduct the analysis at a 1-km resolution for the 2080s (2071–2100; 30-year normal period). Precipitation values were rounded to the nearest 10 mm. This climate tool is based on the PRISM climate model (Daly et al. 2002) and provides a historical mean (1961–1990) to which predicted changes can be compared. Biogeoclimatic zones with similar energy flow, vegetation and soils developed by the BC Forest Service (Meidinger and Pojar 1991) and the US Forest Service (USFS 2008) were used to stratify our analysis by eight geographic provinces and three vegetation zones: alpine (Coastal Alpine), subalpine (Mountain Hemlock), and lowland forest (Northern Coastal Hemlock/Pacific Silver Fir).

2 Climate model results

Our analyses projected an overall regional increase in mean annual temperature (MAT) and mean annual precipitation (MAP), and a decrease in annual precipitation as snow (PAS) (Figs. 3 and 4). Based on projections for five IPCC CMIP5 global climate models (GCMs) and two representative concentration pathways (RCPs), predicted mean annual temperature will increase from a current average (1961–1990) of 3.2 °C to 4.9–6.9 °C (5 GCM range; RCP4.5 scenario) or 6.4–8.7 °C (RCP8.5), mean annual precipitation is predicted to increase from 3130 mm to 3210–3400 mm (3–9 % increase; RCP4.5) or 3320–3690 mm (6–18 % increase; RCP8.5), and total precipitation as snow is anticipated to decrease from 1200 mm to 940–720 mm (22–40 % decrease; RCP4.5) or 720–500 mm (40–58 % decrease; RCP8.5) by the 2080s (2071–2100; 30-year normal period).

Histograms of mean annual temperature (MAT), mean annual precipiation (MAP), and precipitation as snow as water equivalent (PAS). These were stratified by eight biogeoclimatic provinces and three vegetation zones: alpine, subalpine and lowland forest. The historical normals (1961–1990) are presented next to a five global climate model ensemble average with range bars (CCSM4, GFDL-CM3, GISS-E2-H, IPSL-CM5B-LR, and MRI-CGCM3) from the IPCC CMIP5 scenarios RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 for the 2080s (2071–2100; 30-year normal period)

A map series of potential climate change showing the current mean annual temp (MAT), mean annual precipitation (MAP), and precipitation as snow as water equivalent (PAS) compared to corresponding projections for the 2080s (2071–2100; 30-year normal period) using a five global climate model ensemble average (CCSM4, GFDL-CM3, GISS-E2-H, IPSL-CM5B-LR, and MRI-CGCM3) from the IPCC CMIP5 scenarios RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5

Projected changes in climate variables generally followed a high to low pattern along two gradients, from north to south and from mainland to the outer coast; with northern mainland areas showing the greatest change in temperature and precipitation and southern island provinces exhibiting the least (Figs. 3 and 4). For example, averages changes for MAT by the 2080s across vegetation zones showed a north-south and mainland to outer coast trend. Yakutat showed the largest average increase of 2.9 °C (0.9 °C SD over 5 GCMs) in RCP4.5 and Mainland increased 4.7 °C (1.0 °C SD) in RCP8.5; Haida Gwaii exhibited the smallest increase with 2.2 °C (0.7 °C SD) to 3.6 (0.8 °C SD) in projected change. The pattern of change for MAP primarily followed a mainland mountain to low-elevation outer coast trend. Yakutat received the largest average increase in MAP with 290 mm in RCP4.5 (160 mm SD) and 490 mm (220 mm SD) in RCP8.5; Nass Kitimat changed the least with increases of 130 mm in RCP4.5 (100 mm SD) to 270 mm in RCP8.5 (190 mm SD). Changes in PAS showed a mainland to outer coast trend, with Yakutat showing the largest decrease of 540 mm (120 mm SD) in RCP4.5 and 830 mm (130 mm SD) in RCP8.5; Haida Gwaii showed the smallest decline of 280 mm (60 mm SD) in RCP4.5 and 380 mm (30 mm SD) in RCP8.5.

Projected increases in MAT showed a uniform pattern of change on average across vegetation zones with 2.5 °C (0.8 SD; RCP4.5) and 4.2 °C (1.0 SD; RCP8.5). Alpine showed the largest increases in MAP and largest decreases in PAS. Projections for MAP in alpine showed an increase of 240 mm (120 mm SD) in RCP4.5 and 460 mm (200 mm SD) in RCP8.5. Alpine PAS decreased by 540 mm (140 mm SD) in RCP4.5 and 830 mm (120 mm SD) in RCP8.5.

3 Implications for freshwater hydrology and fishes

Currently, the average freshwater discharge in our study area is approximately 780 km3/year, or roughly twice the magnitude of the annual discharge of the Mississippi River Basin (Morrison et al. 2011; Neal et al. 2010). Projected declines in PAS are anticipated to moderate the storage of water as snow, thereby changing the magnitude and timing of seasonal snowmelt runoff (Shanley and Albert 2014). As the rain-snow transition zone increases in elevation in response to increased MAT, less PAS will be stored in seasonal snowfields or ice (Fig. 4). Therefore, runoff patterns are expected to transition toward lower elevation watershed types, shifting from glacial to snow melt and from snow melt to rainfall-dominated (Fig. 2). In southeast Alaska, snow melt-dominated watersheds have already shifted towards higher winter stream flows and lower summer time stream flows during the warm phase of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO; Neal et al. 2002), and based on modeling results, we anticipate this trend will be more prevalent in the future.

Whereas the greatest projected decreases in PAS are for alpine habitats in the mainland provinces (1, 3, 7 and 8), southern island provinces (5 and 6) may show the first signs of transitioning from snow to rain-dominated systems because their mean winter temperature is closer to the freezing threshold. Mainland provinces (1, 3, 7 and 8), however, may be more prone to rain-on-snow and flooding events with the increasing spring and summer temperatures melting subalpine and alpine snowpacks (Fig. 4).

Glacial watersheds currently contribute approximately 30 % of total freshwater discharge in southeast Alaska (Neal et al. 2010), and 95 % of glaciers in this region are losing volume, some at among the highest rates on earth (Berthier et al. 2010; Larsen et al. 2007; Pike et al. 2008). As increased MAT causes glacier mass balance to become more negative, stream flow in glacier-dominated watersheds will initially increase and then eventually decrease as glaciers retreat to occupy only a small fraction (<10 %) of the watershed (Casassa et al. 2009; Moore et al. 2009). This pattern initially may be most pronounced in the southern portions of mainland provinces (3 and 8) with smaller glaciers. In watersheds with a high percentage of ice cover (1 and 3), the initial runoff increase could be substantial (>50 %; Adalgeirsdottir et al. 2006) and will likely exceed climate-driven runoff changes expected from other components of the water budget (Jansson et al. 2003). However, in the long term, loss of ice is anticipated to contribute to lower water yields. Increases in climate-driven discharge are already evident in the few glacial watersheds with temporally extensive stream flow records (Neal et al. 2002).

Runoff from glaciers also has pronounced impacts on water temperature and clarity (Fellman et al. 2014; Hood and Berner 2009; Moore et al. 2009) and riverine concentrations of bioavailable organic matter (Bhatia et al. 2010; Hood et al. 2009), phosphorus (Hodson et al. 2004; Hood and Scott 2008), and micronutrient iron (Schroth et al. 2011). The unique suite of solutes associated with glacial runoff can influence biogeochemistry and productivity in downstream freshwater and near-shore marine ecosystems (e.g., Fellman et al. 2010). Stream flow and stream temperature affect production and timing of benthic fauna that forms much of the food base for freshwater fishes in lowland forest streams (Wipfli 1997; Wipfli and Baxter 2010). Changes in flow, temperature, and nutrient dynamics in freshwater ecosystems influence fish abundance across life-history stages (Bryant 2009). For example, high-flows during the winter incubation period increase salmonid embryo mortality, causing steep declines in adult returns (e.g., pink salmon [O. gorbuscha] and coho salmon [O. kisutch] in Glacier Bay; Milner et al. 2013).

Salmonids are a cold-water species with high critical thermal maxima (e.g., ~29 °C in juvenile coho salmon; Konecki et al. 1995), although most salmonid functions (incubation, feeding, growth) are compromised when temperatures exceed ~12–15 °C (Richter and Kolmes 2005). Dramatic declines in gamete viability have been observed in pink salmon in southeast Alaska when stream temperatures exceed 15 °C during the spawning run (A. Gharrett, pers. communication, 2013). As ectotherms, fish are strongly governed by temperature. Demographic studies have shown that salmonid run timing has shifted and is more temporally compressed (Kovach et al. 2012, 2013, 2015). For example, coho salmon currently return to Auke Creek in southeast Alaska to spawn 17 days earlier than they did in the 1970s (Kovach et al. 2013). However, increased summer temperatures in Auke Lake increase the biomass of juvenile coho and sockeye salmon (O. nerka) smolts the following fall (Kovach et al. 2014), implying that moderately higher temperatures will positively affect some salmon life history stages while negatively impacting others. The diversity of salmon species and life histories will likely be an important source of resilience to climate change throughout the northern coastal temperature rainforest in the future (Kovach et al. 2015).

Winter high flows may be particularly important to monitor for scour of salmon eggs from the gravel (Montgomery et al. 1999; Shanley and Albert 2014). The nests of larger females should be more resistant to scour; however increasing temperatures during the marine phase can lead to smaller adult size in salmonids (Jonsson et al. 2012), thus compounding the effects of warming. According to the climate projections, scour may initially be most pronounced in northern mainland provinces (1 and 3) with increased MAT and MAP. Acute temperature-driven physiological and from snow melt to rainfall-dominated likely to occur during summer months in provinces with a higher likelihood of low flows and diminished snowpack (5, 6 and 7), although increased MAP could mediate lower flows in some watersheds. Temperature-related phenological shifts are expected throughout a fish’s life cycle, but phenological changes are likely to be most pronounced during spawning migrations (mid-summer to fall). Marine-derived nutrients and energy are anticipated to be less available to those species whose own phenologies do not track shifts in these migrations. However, because marine subsidies propagate through freshwater and riparian ecosystems (Wipfli and Baxter 2010), effects might occur in other seasons as well.

Warmer temperatures are expected to slowly influence the lowland forest landscape towards a greater proportion of deciduous trees, especially Alnus spp. (Implications for terrestrial ecosystems—vegetation and wildlife section, this paper), leading to allochthonous litter inputs that are more concentrated in autumn and higher food quality for riparian and aquatic food webs (Wipfli 1997; Wipfli and Baxter 2010). Alnus, an N fixer, rapidly colonizes deglaciating watersheds and will therefore potentially increase nitrate abundance in adjacent streams through increases in soil nitrogen pools (Hood and Scott 2008).

Among glacial watersheds in mainland provinces (1, 3, and 8), near-term increases in summer glacial runoff is anticipated to buffer increases in water temperatures, potentially reducing the likelihood that marginal glacial streams become optimal for spawning and development, but in the long term, diminishing glacial influence may also lead to warmer, more thermally optimal streams supporting increased production of food for stream-rearing salmonids as well as conditions for salmon development and spawning (Fellman et al. 2014; Milner et al. 2009). For example, the warm phase of the PDO has also been correlated with high commercial harvest of salmon in Alaska (Mote et al. 2003). The effect of climate change on local marine subsidies will depend on the amount of suitable spawning habitat, species’ phenologies, and fluctuations in anadromous fish populations.

Sea-level is projected to rise under current climate change scenarios, due to thermal expansion of seawater, melting of land ice, and changes in liquid storage on land (Church et al. 2013). IPCC projections for 2081–2100 range from 0.4 to 0.63 m above 1986–2005 levels (ibid), and vary considerably geographically due to variable changes in ocean temperature and salinity related to changes in ocean circulation. In northern southeast Alaska (1, 2, and northern 3), however, sea level is decreasing by as much as ~3 cm/year as a result of isostatic rebound from glacier mass loss (Larsen et al. 2005). Sea-level changes have important implications for coastal tidal wetlands and salmonid rearing habitats (e.g., Bryant 2009). Some models predict that 20–60 % of the world’s tidal wetlands will be lost this century due to sea level rise (e.g., Craft et al. 2009).

4 Implications for terrestrial ecosystems—vegetation and wildlife

A key feature of current vegetation patterns is the disturbance ecology of frequent wind, snow and ice storms from fall through early spring (Alaback et al. 2013). These winter storms not only constrain growing seasons for vegetation, but also have important effects on associated soil ecosystems (D’Amore and Hennon 2006), nutrient cycling (D’Amore et al. 2010) and forest regeneration rates (Alaback 1982). For example, Alaska yellow-cedar (Callitropsis nootkatensis) decline appears to be closely related to changes in transient snow—reduced snowpacks affect soil insulation, causing fine root damage and mortality in areas with poor drainage (Hennon et al. 2012).

Given projected increases in MAT, we expect distribution shifts in individual species and ecological communities (Hamann and Wang 2006; Wolken et al. 2011). Some wide spread genetically diverse species, such as western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) and Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis), are expected to colonize new habitats rapidly (Farr and Harris 1979; Gavin and Hu 2006). Other species, such as the cedars and many understory plants are expected to change more slowly, due to both regeneration requirements and low genetic diversity (Gilliam 2007; Bunnell and Kremsater 2012) that may lead to new plant communities (Oakes et al. 2014).

Projected increases in MAP suggest that lowland coastal forests will remain characteristically wet places (Fig. 3). Hydrologic changes (previous section, this paper) in the occurrence and intensity of flooding events could lead to changes in the nature and extent of riparian forest disturbance dynamics (Naiman et al. 1998). Assuming that seasonality of precipitation does not change significantly, fire will remain unimportant as a disturbance agent, but higher MAT is anticipated to increase the incidence and severity of insects and disease in lowland forests (Haughian et al. 2012; Hennon et al. 2012). Exceptions to this general rule are anticipated where periodic droughts and fires do occasionally occur i.e., in the southern provinces (6, 7 and 8) (Haughian et al. 2012). This impact is projected to increase in severity, as MAT is also projected to increase (Figs. 3 and 4). Decomposition rates are also anticipated to increase, and some wetlands (bogs, fens etc.) may become productive forests, as has occurred in the past (e.g., Neiland 1971).

Subalpine and alpine habitats are anticipated to undergo more rapid changes than lowland forests. For example, Wang et al. (2012a) suggest that British Columbia’s coastal alpine habitat will shift upward in elevation more than 200 m by the 2080s. Alpine habitat MATs are projected to exceed current subalpine habitat MAT by the 2080s (temperatures that trees currently grow) in all the island provinces (2, 4, 5, and 6) in RCP4.5, and most of the mainland provinces (3, 7, and 8) with the exception of Yakutat in RCP8.5. At the same time, accumulated PAS in alpine habitats will on average decline by 15–54 % across provinces for RCP4.5 and 27–74 % in RCP8.5. The combination of warmer alpine MAT and lower snowpacks are anticipated to raise the elevation of treeline (Wang et al. 2012a), moving treeline to mountaintops, and resulting in a regional loss of high elevation tundra ecosystems. Subalpine vegetation can occur at relatively low elevations due to the persistence of snow in the late spring and early summer, and the high frequencies of snow avalanches (due to steep topography and wet heavy snow). With projected reductions in snowpack, however, the lower boundary of the subalpine habitats is anticipated to increase in elevation.

Climate, vegetation, and weather interact to affect wildlife in the region through food availability and habitat quality, which affect species fitness and demography. Populations of animals and resource selection in northern climates are often determined by the weather severity (Brinkman et al. 2011; Person and Russell 2010). For example, the availability of salmon greatly influences habitat quality for brown bear (Ursus arctos) (Hilderbrand et al. 1999). When salmon populations move or decline as a result of weather and climate-driven changes in hydrology, brown bear populations will also move or decline. Persistent deep alpine and subalpine snow forces mountain goats (Oreamnos americanus) and Sitka black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus sitkensis) to move to lowland forest habitat (Schoen and Kirchhoff 1990; White et al. 2011); condensing winter range and reducing habitat carrying capacity. Deep snow also increases energetic costs by hindering locomotion and restricting movement among forage patches (Parker et al. 1984). Cold, rainy weather in the spring potentially increases thermoregulatory demands and parental investment in wildlife species.

Future climate predictions, however, may cumulatively reduce the severity of ecological and niche limitations on wildlife. Projected increases in MAT may expand lowland forest habitat available to ungulates during the winter and reduce energetic costs (Parker et al. 1984). Future projections of PAS suggest that deep snow may no longer be a limiting factor for deer in the southern and island provinces (5, 6 and 7). Where PAS is still anticipated in the future (1, 2, 3 and 4), snow accumulation and persistence may decline and alleviate winter stress for wildlife. Further, a longer growing season may increase food availability for wildlife in the spring when energy demand of winter-stressed individuals is high. Any negative effects of potentially increasing rain-on-snow and other icing events may be short lived because winter temperatures in the region typically fluctuate close to freezing.

Wildlife habitats associated with coastal and estuarine wetlands are anticipated to undergo changes due to sea-level rise and an increase in the frequency and severity of storm surges (Michener et al. 1997). The direct ecological effects of sea-level rise include coastal inundation, flood damage, increased erosion, and saline water intrusion (Nicholls and Cazenave 2010); with associated changes in wetland community structure (Craft et al. 2009). Wildlife species dependent on these habitats, such as brown bears (Schoen et al. 1994), Vancouver Canada geese (Branta canadensis fulva; Fox 2008), and shorebirds (Iverson et al. 1996) are anticipated to see declines in essential seasonal habitats in southern provinces not experiencing isostatic rebound (6, 7, 8 and southern 3, 4, and 5; Larsen et al. 2005).

Endemic species may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change due to habitat change coupled with limited migration potential in the naturally fragmented and glacier-bounded island archipelago. As MAP and MAT increase in the island provinces (2, 4, 5, 6 and portions of 7), which tend to be the hotspots of endemism in this area, critical aspects of ecological niches are anticipated to also change, and these conditions may trigger extirpations (Cook and MacDonald 2013).

Temperature-related shifts of wildlife ranges northward (Root et al. 2003) may increase interspecific competition, especially for endemic species. However, the isolated geography may slow immigration to the region compared to other parts of North America. Little is known how interactions in wildlife communities may change as the climate becomes more tolerable for southern species currently at the northern extent of their range.

5 Implications for ecosystem service benefits

Increased MAT and MAP coupled with decreased PAS are anticipated to primarily affect ecosystem services that regulate water quality, water quantity, greenhouse gas fluxes and nutrient fluxes (or subsidies). Changing hydrologic regimes could alter the distribution and productivity of fisheries, dependability on hydropower, and desirable tourism activities (e.g., wildlife viewing)—three key pillars of local and regional economies in southeast Alaska and northern coastal British Columbia (Crone and Mehrkens 2013).

The legacy of industrial-scale forest management in southeast Alaska and northern coastal British Columbia has continued influence on both the supply and demand of forest products in the region. Harvesting of wood fiber and fuel is seen as less sensitive to projected climatic changes than the existing constraints on logging in the region (Albert and Schoen 2013; Beier 2011). However, the climate-driven decline of Alaska yellow-cedar across the region has resulted in localized but geographically widespread areas (2, 4, and 5) of high-value salvage logs that may be processed locally into high value wood products (Beier et al. 2008a). Accelerated forest growth rates, if driven by MAT warming, may in turn increase the quantity but decrease the tight grain quality (especially for spruce and cedar) of forest products from second-growth forests, relative to those harvested from primary forests during the 20th century. Greater attention to greenhouse emissions and renewable energy alternatives may promote more widespread use of pre-commercial second-growth forests for biomass energy.

Climate change impacts on ecosystem services related to fish and wildlife populations will undoubtedly influence their many beneficiaries in the region, which include subsistence, commercial and recreational users (Beier et al. 2008b). Wild food sources remain vital to cultural activities for residents, especially in remote First Nation and Alaskan Native communities. Commercial fisheries remain essential in many communities in addition to a rapidly growing guide and outfitter sector (Colt et al. 2007). For fisheries, climate changes that disrupt the regular timing and distribution of salmon runs (Kovach et al. 2013) may reduce fishing success. Conflicts among fisheries may emerge if potentially negative impacts reduce the allowable catch. Related changes that disrupt estuarine systems and near-shore food webs (Schoch et al. 2013) could also impact the availability of shellfish that support locally important subsistence and personal use fisheries. On land, Sitka black-tailed deer are the most harvested game species in southeast Alaska (Brinkman et al. 2011) and because their population movements are sensitive to changing snow patterns, hunters may experience increased difficulty locating deer on traditional hunting grounds or in accessible areas (Brinkman et al. 2009). Overall, if traditional hunting and fishing grounds become less productive or predictable due to climate change, it remains to be seen whether residents, business owners and visitors will continue to either seek or ‘capture’ these ecosystem service benefits.

6 Synthesis and conclusion

Our collaborative synthesis of potential climate change impacts across biophysical systems highlights the coupling of social and ecological dynamics that characterize the northern coastal temperate rainforest of North America. The sharp environmental gradient from icefields to coastal estuaries creates a unique climate sensitivity to warmer and seasonally wetter climate projections with elevated snowlines. Globally, projected increases in days above freezing are only comparable to the southern Andes in South America as well as central and northern parts of Europe and Asia (Meehl et al. 2004; Sillmann et al. 2013). The southern Andes and northern Europe contain temperate rainforest ecosystems (Dellasala et al. 2011) that may provide opportunities for shared learning internationally. Finer scale monitoring and systematic placement of additional long-term hydro-meteorological stations will improve capacity to evaluate assumptions and uncertainty associated with global climate models that do not account for the significance of local variability (e.g., Wright and Stevens 2012). Greater research integration (e.g., interagency collaborations) will provide better insights into the complexity and coupling within and between ecosystems and climate for policy and planning direction. Most information needs cited as a part of this review process (Table 1) relate to improved modeling of changes in hydrology, and the social and ecological consequences of those changes. Immediate recognition and prioritization of our findings is critical because of the rapid rate of change anticipated, and the relatively high dependence on the cultural and provisional ecosystem services in the northern coastal temperate rainforest of southeast Alaska and British Columbia.

References

Adalgeirsdottir G, Johannesson T, Bjornsson H, Palsson F, Sigurdsson O (2006) Response of Hofsjokull and southern Vatnajokull, Iceland, to climate change. J Geophys Res 111. doi:10.1029/2005JF000388

Alaback PB (1982) Dynamics of understory biomass in Sitka Spruce Western Hemlock forests of southeast Alaska. Ecology 63:1932–1948

Alaback PB (1996) Biodiversity patterns in relation to climate in the temperate rainforests of North America. In: Lawford R, Alaback PB, Fuentes ER (eds) High latitude rain forests of the west coast of the Americas: climate, hydrology, ecology and conservation. Ecological studies 113. Springer, Berlin, pp 105–133

Alaback PB, Nowacki G, Saunders S (2013) Disturbance ecology of the temperate rainforests of Southeast Alaska and adjacent British Columbia. In: Schoen JW, Orians G (eds) North Pacific temperate rainforests: ecology and conservation. University of Washington Press, Seattle, pp 73–88

Albert DM, Schoen JW (2013) Use of historical logging patterns to identify disproportionately logged ecosystems within temperate rainforests of southeastern Alaska. Conserv Biol 27:774–784

Beier C (2011) Factors influencing adaptive capacity in the reorganization of forest management in Alaska. Ecol Soc 16:40

Beier C, Sink SE, Hennon PE, D’Amore DV, Juday GP (2008a) Twentieth-century warming and the dendroclimatology of declining yellow-cedar forests in southeastern Alaska. Can J For Res 38:1319–1334

Beier CM, Patterson TM, Chapin FS III (2008b) Ecosystem services and emergent vulnerability in managed ecosystems: a geospatial decision-support tool. Ecosystems 11:923–938

Berthier E, Schiefer E, Clarke GKC, Menounos B, Remy F (2010) Contribution of Alaskan glaciers to sea-level rise derived from satellite imagery. Nat Geosci 3:92–95

Bhatia MP, Das SB, Longnecker K, Charette MA, Kujawinski EB (2010) Molecular characterization of dissolved organic matter associated with the Greenland ice sheet. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 74:3768–3784

Brinkman TJ, Chapin FS III, Kofinas GP, Person DK (2009) Linking hunter knowledge with forest change to understand changing deer harvest opportunities in intensively logged landscapes. Ecol Soc 14:36

Brinkman TJ, Person DK, Chapin FS III, Smith WP, Hundertmark KJ (2011) Estimating abundance of Sitka black-tailed deer using DNA from fecal pellets. J Wildl Manag 75:232–242

Bryant MD (2009) Global climate change and potential effects on Pacific salmonids in freshwater ecosystems of southeast Alaska. Clim Chang 95:169–193

Bunnell FL, Kremsater LL (2012) Migrating like a herd of cats: climate change and emerging forests in British Columbia. BC J Ecosyst Manag 13:1–24

Casassa G, Lopex P, Pouyand B, Escobar F (2009) Detection of change in glacial runoff in alpine basins: examples form North America, the Alps, central Asia and the Andes. Hydrol Process 23

Church JA, Clark PU, Cazenave A, Gregory JM, Jevrejeva S, Levermann A, Merrifield MA, Milne GA, Nerem RS, Nunn PD, Payne AJ, Pfeffer WT, Stammer D, Unnikrishnan AS (2013). Climate Change 2013: The physical science basis. Contribution of the working group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. pp 1137–1216

Colt S, Dugan D, Fay G (2007) The regional economy of southeast Alaska. Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of Alaska Anchorage, Anchorage, Alaska. www.iser.uaa.alaska.edu/Publications/SoutheastEconomyOverviewfinal4.pdf. Accessed 11 Oct 2013

Cook JA, MacDonald SO (2013) Island Life: coming to grips with the insular nature of southeast Alaska and adjoining coastal British Columbia. In: Schoen JW, Orians G (eds) North Pacific temperate rainforests: ecology and conservation. University of Washington Press, Seattle, pp 19–42

Craft C, Clough J, Ehman J, Joye S, Park R, Pennings S, Guo HY, Machmuller M (2009) Forecasting the effects of accelerated sea-level rise on tidal marsh ecosystem services. Front Ecol Environ 7:73–78

Crone LK, Mehrkens JR (2013) Indigenous and commercial uses of the natural resources of the north pacific rainforest with a focus on southeast Alaska and Haida Gwaii. In: Orians G, Schoen J (eds) North Pacific temperate rainforests: ecology and conservation. University of Washington Press, Seattle, pp 89–126

Daly C, Gibson WP, Taylor GH, Johnson GL, Pasteris P (2002) A knowledge-based approach to the statistical mapping of climate. Clim Res 22:99–113

D’Amore DV, Hennon PE (2006) Evaluation of soil saturation, soil chemistry, and early spring soil and air temperatures as risk factors in yellow-cedar decline. Glob Chang Biol 12:524–545

D’Amore DV, Fellman JB, Edwards RT, Hood E (2010) Controls on dissolved organic matter concentrations in soils and streams from forested wetland and sloping bog in southeast Alaska. Ecohydrology 3:249–261

Dellasala D, Alaback PB, Spribille T, von Wehrden H, Nauman RS (2011) Just what are temperate and boreal rainforests? In: Dellasala DA (ed) Temperate and boreal rainforests of the world. Island Press, Washington

Edwards RT, D’Amore DV, Norberg E, Biles F (2013) Riparian ecology, climate change, and management in North Pacific Coastal Rainforests. In: Orians G, Schoen J (eds) North Pacific temperate rainforests: ecology and conservation. University of Washington Press, Seattle, pp 43–72

Evans MR (2012) Modelling ecological systems in a changing world. Phil Trans R Soc B 367:181–190

Farr WA, Harris S (1979) Site index of Sitka spruce along the Pacific coast related to latitude and temperatures. For Sci 25:145–153

Fellman J, Spencer RGM, Edwards R, D’Amore DV, Hernes PJ, Hood E (2010) The impact of glacier runoff on the biodegradability and biochemical composition of terrigenous dissolved organic matter in near-shore marine ecosystems. Mar Chem 121:112–122

Fellman JB, Nagorski S, Pyare S, Vermilyea AW, Scott D, Hood E (2014) Stream temperature response to variable glacier cover in coastal watersheds of southeast Alaska. Hydrol Process 28:2062–2073. doi:10.1002/hyp.9742

Fox T (2008) Winter ecology of Vancouver Canada geese in southeast Alaska. Thesis, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho

Gavin DG, Hu FS (2006) Spatial variation of climatic and non-climatic controls on species distribution: the range limit of Tsuga heterophylla. J Biogeogr 33:1384–1396

Gilliam FS (2007) The ecological significance of the herbaceous layer in temperate forest ecosystems. Bioscience 57:845–858

Halupka KC, Willson M, Bryant MD, Everest FH, Gharrett AJ (2003) Conserving of population diversity of Pacific salmon in southeast Alaska. N Am J Fish Manag 23:1057–1086

Hamann A, Wang T (2006) Potential effects of climate change on ecosystem and tree species distribution in British Columbia. Ecology 87:2773–2786

Haughian SR, Burton PJ, Taylor SW, Curry CL (2012) Expected effects of climate change on forest disturbance regimes in British Columbia. BC J Ecosyst Manag 13:1–24

Hennon PE, D’Amore DV, Schaberg PG, Wittwer DT, Shanley CS (2012) Shifting climate, altered niche, and a dynamic conservation strategy for Yellow-cedar in the North Pacific coastal rainforest. Bioscience 62:147–158

Hilderbrand GV, Schwartz CC, Robbins CT, Jacoby ME, Hanley TA, Arthur SM, Servheen C (1999) Importance of meat, especially salmon, to body size, population productivity, and conservation of North American brown bears. Can J Zool 77:132–138

Hodson A, Mumford P, Lister D (2004) Suspended sediment and phosphorus in proglacial rivers: bioavailability and potential impacts upon the P status of ice-marginal receiving waters. Hydrol Process 18:2409–2422

Hood E, Berner L (2009) Effects of changing glacial coverage on the physical and biogeochemical properties of coastal streams in southeastern Alaska. J Geophys Res 114, G03001. doi:10.1029/2009JG000971

Hood E, Scott DT (2008) Riverine organic matter and nutrients in southeast Alaska affected by glacial coverage. Nat Geosci 1:583–587

Hood E, Fellman J, Spencer RGM, Hernes PJ, Edwards R, D’Amore DV, Scott D (2009) Glaciers as a source of ancient and labile organic matter to the marine environment. Nature 462:1044–1047

Iverson GC, Warnock SE, Butler RW, Bishop MA, Warnock N (1996) Spring migration of western sandpipers along the Pacific coast of North America: a telemetry study. Condor 98:10–21

Jansson P, Hock R, Schneider T (2003) The concept of glacier storage: a review. J Hydrol 282:116–129

Jonsson B, Finstad AG, Jonnson N (2012) Winter temperature and food quality affect age at maturity: an experimental test with Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Can J Fish Aquat Sci 69:1817–1826

Konecki JT, Woody CA, Quinn TP (1995) Critical thermal maxima of coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) fry under field and laboratory acclimation regimes. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 73:993–996

Kovach RP, Gharrett AJ, Tallmon DA (2012) Genetic change for earlier migration timing in a pink salmon population. Proc R Soc Lond B 279:3861–3869

Kovach RP, Joyce JE, Echave JD, Lindberg MS, Tallmon DA (2013) Earlier migration timing, decreasing phenotypic variation, and biocomplexity for multiple salmonid species. PLoS ONE 8:e53807

Kovach RP, Joyce JE, Vulstek SC, Barrientos EB, Tallmon DA (2014) Variable effects of climate and density on the juvenile ecology of two salmonids in an Alaskan lake. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 71:799–807

Kovach RP, Ellison SC, Pyare S, Tallmon DA (2015) Temporal patterns of adult salmon migration across Southeast Alaska. Glob Chang Biol. Accepted. doi:10.1111/gcb.12829

Larsen CF, Motyka RJ, Freymueller JT, Echelmeyer KA, Ivins ER (2005) Rapid viscoelastic uplift in southeast Alaska caused by post-Little Ice Age glacial retreat. Earth Planet Sci Lett 237:548–560. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2005.06.032

Larsen CF, Motyka RJ, Arendt AA, Echelmeyer KA, Geissler PE (2007) Glacier changes in southeast Alaska and northwest British Columbia and contribution to sea level rise. J Geophys Res 112. doi:10.1029/2006JF000586

Leighty WW, Hamburg SP, Caouette JP (2006) Effects of management on carbon sequestration in forest biomass in southeast Alaska. Ecosystems 9:1051–1065

Meehl GA, Tebaldi C, Nychka D (2004) Changes in frost days in simulations of twentyfirst century climate. Clim Dyn 23:495–511

Meidinger DV, Pojar J (1991) Ecosystems of British Columbia, Special Report No. 6, BC Ministry of Forests. Victoria, B.C.

Michener WK, Blood ER, Bildstein KL, Brinson MM, Garden LR (1997) Climate change, hurricanes and tropical storms, and rising sea level on coastal wetlands. Ecol Appl 7:770–801

Milner AM, Brown LE, Hannah DM (2009) Hydroecological response of river systems to shrinking glaciers. Hydrol Process 23:62–77

Milner AM, Robertson AL, McDermott MJ, Klarr MJ, Brown LE (2013) Major flood disturbance alters river ecosystem evolution. Nat Clim Chang 3:137–141

Montgomery DR, Beamer EM, Pess GR, Quinn TP (1999) Channel type and salmonid spawning distribution and abundance. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 56:377–387

Moore RD, Fleming SW, Menounos B, Wheate R, Fountain A, Stahl K, Holm K, Jakob M (2009) Glacier change in western North America: influences on hydrology, geomorphic hazards and water quality. Hydrol Process 23:42–61

Morrison J, Foreman MGG, Masson D (2011) A method for estimating monthly freshwater discharge affecting British Columbia. Atmosphere-Ocean 50:1–8

Mote PW, Parson EA, Hamlet AF, Keeton WS, Lettenmaier D, Mantua N, Miles EL, Peterson DW, Peterson DL, Slaughter R, Snover AK (2003) Preparing for climatic change: the water, salmon, and forests of the Pacific Northwest. Clim Chang 61:45–88

Naiman RJ, Fetherston KL, McKay SJ, Chen J (1998) Riparian forests. In: Naiman RJ, Bilby RE (eds) River ecology and management: lessons from the Pacific Coastal Ecoregion. Springer, New York

Neal EG, Walter MT, Coffeen C (2002) Linking the pacific decadal oscillation to seasonal stream discharge patterns in southeast Alaska. J Hydrol 263:188–197

Neal EG, Hood E, Smikrud K (2010) Contribution of glacier runoff to freshwater discharge into the Gulf of Alaska. Geophys Res Lett 37, L06404. doi:10.1029/2010GL042385

Neiland B (1971) The forest-bog complex of southeast Alaska. Vegetatio 22:1–63

Nicholls RJ, Cazenave A (2010) Sea level rise and its impact on coastal zones. Science 328:1517–1520

Oakes LE, Hennon PE, O’Hara KL, Dirzo R (2014) Long-term changes in a temperate forest impacted by climate change. Ecosphere 5:art135. doi:10.1890/ES14-00225.1

Parker KL, Robbins CT, Hanley TA (1984) Energy expenditures for locomotion by mule deer and elk. J Wildl Manag 48:474–488

Patterson TM, Coelho DL (2009) Ecosystem services: foundations, opportunities, and challenges for the forest products sector. For Ecol Manag 257:1637–1646

Person DK, Russell AL (2010) Correlates of mortality in an exploited wolf population. J Wildl Manag 72:1540–1549

Pike RG, Spittlehouse DL, Bennett KE, Egginton VN, Egginton VN, Tschaplinski PJ, Murdock TQ, Werner AT (2008) Climate change and watershed hydrology: Part II—hydrologic implications for British Columbia. Streamline Watershed Manag Bull 11:8–13

Radic V, Clarke GKC (2011) Evaluation of IPCC models’ performance in simulating late-twentieth-century climatologies and weather patterns over North America. J Clim 24:5257–5274

Richter A, Kolmes SA (2005) Maximum temperature limits for Chinook, coho, and chum salmon, and steelhead trout in the Pacific Northwest. Rev Fish Sci 12:23–49

Root TL, Price J, Hall KR, Schneider SH, Rosenzweig C, Pounds AJ (2003) Fingerprints of global warming on wild animals and plants. Nature 421:57–60

Schoch GM, Albert DM, Shanley CS (2013) An estuarine habitat classification for a complex fjordal island archipelago. Estuar Coasts. doi:10.1007/s12237-12013-19622-12233

Schoen JW, Kirchhoff MD (1990) Seasonal habitat use by Sitka black-tailed deer on Admiralty Island, Alaska. J Wildl Manag 54:371–378

Schoen JW, Flynn RW, Suring LH, Titus K, Beier LR (1994) Habitat-capability model for brown bear in southeast Alaska. Int Conf Bear Res Manag 9:327–337

Schroth AW, Crusius J, Chever F, Bostick BC, Rouxel OJ (2011) Glacial influence on the geochemisty of riverine iron fluxes to the Gulf of Alaska and effects of deglaciation. Geophys Res Lett 38. doi:10.1029/2011GL048367

Shanley CS, Albert DA (2014) Climate change sensitivity index for Pacific Salmon habitat in southeast Alaska. PLoS ONE 9(8):e104799. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104799

Sillmann J, Kharin VV, Zwiers FW, Zhang X, Bronaugh D (2013) Climate extremes indices in the CMIP5 multimodel ensemble: Part 2. Future climate projections. J Geophys Res Atmos 118:2473–2493. doi:10.1002/jgrd.50188

Simpson JJ, Hufford GL, Daly C, Berg JS, Fleming MD (2005) Comparing maps of mean monthly surface temperature and precipitation for Alaska and adjacent areas of Canada produced by two different methods. Arctic 58:137–161

Temple N (2005) Salmon in the Great Bear Rainforest. Raincoast Conservation Society, Victoria, BC, Canada. www.raincoast.org/files/publications/reports/Salmon-in-the-GBR.pdf. Accessed 11 Oct 2013

USFS (2008) Tongass land and resource management plan: final Environmental Impact Statement. Volume 1 R10-MB-603c. Alaska Region, Juneau, Alaska

Walsh JE, Chapman WL, Romanovsky V, Christensen JH, Stendel M (2008) Global climate model performance over Alaska and Greenland. J Clim 21:6156–6174

Wang T, Campbell EM, O’Neill GA, Aitken SN (2012a) Projecting future distributions of ecosystem climate niches: uncertainties and management applications. For Ecol Manag 279:128–140

Wang T, Hamann A, Spittlehouse DL, Murdock TQ (2012b) ClimateWNA—high-resolution spatial climate data for western North America. J Appl Meteorol 51:16–29

Waters E (2010) Economic contributions and impacts of salmonid resources in southeast Alaska. TCW Economics, Sacramento, CA. www.americansalmonforest.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/EconReportFull.pdf. Accessed 11 Oct 2013

White KS, Pendleton GW, Crowley D, Griese H, Hundertmark KJ, McDonough T, Nichols L, Robus M, Smith CA, Schoen JW (2011) Mountain goat survival in coastal Alaska: effects of age, sex, and climate. J Wildl Manag 75:1731–1744

Wipfli MS (1997) Terrestrial invertebrates as salmonid prey and nitrogen sources in streams: contrasting old-growth and young-growth riparian forests in southeastern Alaska. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 54:1259–1269

Wipfli MS, Baxter CV (2010) Linking ecosystems, food webs, and fish production: subsidies in salmonid watersheds. Fisheries 35:373–387

Wolken JM, Hollingsworth TN, Rupp TS, Chapin FS, Trainor SF, Barrett TM, Sullivan PF, McGuire AD, Euskirchen ES, Hennon PE, Beever EA, Conn JS, Crone LK, D’Amore DV, Fresco N, Hanley TA, Kielland K, Kruse JJ, Patterson T, Schuur EAG, Verbyla DL, Yarie J (2011) Evidence and implications of recent and projected climate change in Alaska’s forest ecosystems. Ecosphere 2:art124

Wright PA, Stevens T (2012) Designing a long-term ecological change monitoring program for BC Parks: ecological monitoring in British Columbia’s parks. BC J Ecosyst Manag 13:87–100

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Wilburforce Foundation and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation for funding C.S. Shanley to conduct the climate modeling and manuscript drafting. Wilburforce, along with the North Pacific Landscape Conservation Cooperative, provided support to M. I. Goldstein and S. Pyare for stimulating cross-boundary collaboration. Alaska EPSCoR NSF award #OIA-1208927 and the state of Alaska supported S. Pyare during the drafting of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Shanley, C.S., Pyare, S., Goldstein, M.I. et al. Climate change implications in the northern coastal temperate rainforest of North America. Climatic Change 130, 155–170 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-015-1355-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-015-1355-9