Abstract

Therapist anxious distress when delivering child mental health treatment has been understudied as a factor that contributes to the underuse of some evidence-based interventions (EBIs), such as time-out for children with disruptive behaviors. This study investigated therapist anxious avoidance of time-out using a three-part, vignette-based survey design. Therapists (n = 198) read a vignette of an in-session time-out and reported on their personal anxious distress and likelihood of discontinuing the implementation of time-out. Therapists also provided open-ended descriptions of challenges to delivering time-out. Therapists reported moderate anxious distress at time points 1 and 2 and lower anxious distress at time 3 when the time-out had resolved. Most therapists endorsed some avoidance of time-out. Binomial logistic regression analyses indicated that increased anxious distress corresponded with an increased probability of avoiding time-out delivery in the future. Qualitative reports expanded on challenges to implementing time-out. Findings suggest the importance of addressing therapist anxious distress when implementing children’s mental health treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Providing evidence-based treatment to children and families is critical for ensuring the quality and effectiveness of care. However, most therapists do not provide evidence-based treatment [1, 2]. The field of implementation science has attempted to identify factors that impact the implementation and dissemination of evidence-based practices in community mental health agencies, to ensure that clients are receiving effective care. Leading implementation science frameworks focus on contextual factors [3], organizational factors [4], intervention characteristics [5], therapist factors [6, 7], and the interaction between these factors [8]. Models focusing on therapist factors have primarily investigated therapist attitudes [9], knowledge [10], and self-efficacy [11]. However, training therapists to increase knowledge of evidence-based treatments has not been found to ensure improve client outcomes [12]. Similarly, therapist attitudes towards evidence-based practices have been found to impact their uptake and sustainment, however attitudes do not entirely account for the omission of empirically-supported treatments in care provision [13].

Therapist anxiety has been proposed as an additional factor impacting the uptake of EBIs [14, 15]. In fact, preliminary research has suggested that higher rates of therapist anxiety, measured in one study as intolerance of uncertainty, are related to decreased use of evidence-based interventions, specifically exposure-based and behavioral experiments [16]. A systematic review of therapist non-adherence to evidence-based treatments identified six studies that investigated the role of therapist anxiety in treatment delivery [17]. Identified studies focused primarily on the delivery of CBT and exposure-based or behavioral interventions and found associations between therapist anxiety and decreased or minimized use of treatment elements likely to cause temporary anxiety in patients (i.e. exposures and behavioral experiments). Therapists have been found to prefer more emotionally benign elements of treatment, worrying less about providing psychoeducation [18] and opting for relaxation strategies over exposure-based interventions [1].

The impact of therapist anxiety on EBI delivery has been discussed primarily in the context of anxiety disorders [19, 20], OCD [21] eating disorders [16, 18], and suicide prevention [22, 23]. It has not yet been investigated in the context of parent behavior therapy, the leading treatment for childhood disruptive behaviors [24], despite ongoing obstacles to community implementation of behavioral parent therapy. Teaching caregivers to use time-out for youth disruptive behaviors is one component of treatment that has been identified as a key element in treating childhood externalizing symptoms (e.g. aggression, hyperactivity, oppositionality) [25, 26]. Time-out is a non-coercive behavioral strategy involving a temporary removal of parental attention and proximity [24]. When used effectively, time-out can ameliorate parental discipline by providing consistent and predictable limits and consequences, and offering children an opportunity to develop self-regulation skills [27]. Time-out is taught within the context of a warm, nurturing relationship as a response to aggression or other conduct problems. Treatments that include time-out either offer didactic instruction on how to implement time-out at home, or coach parents to practice delivering time-out in session [28]. When delivering in-session time-outs, therapists coach caregivers to implement the strategy effectively through in-vivo coaching, which has been found to improve the uptake of new parenting skills [29].

Despite positive outcomes associated with teaching caregivers to use time-out, it is the least used component of behavioral parent training (BPT) by community therapists [30]. Therapists have described time-out as unacceptable, reported negative beliefs about the strategy, and expressed concern that it may worsen child behavior and anxiety [31]. Many recent articles have tried to understand impediments to the use of time-out in children’s mental health treatment [32,33,34], with some focusing on therapist perspectives [35]. No articles to date have specifically investigated the role of a therapist’s experience of anxiety while implementing time-out and its impact on time-out implementation. Given that time-out can elicit temporary increases in both child and caregiver distress, especially when it is first practiced, it is possible that therapists similarly experience an increase in anxiety and distress (hereafter referred to as anxious distress) when teaching time-out in session, potentially leading to avoidance of using this important skill. Children’s emotions can become heightened, crying and screaming when time-out is implemented for the first time, eliciting an urge to end the time-out in order to appease the dysregulated child. Because delivering time-out can induce temporary anxiety for the child, caregiver, and therapist, it is an ideal intervention through which to study the role of therapist anxiety in implementation and potential maladaptive avoidance [14].

This study is the first attempt to empirically examine whether therapist anxious distress leads to avoidance of teaching parents to use time-out, a core evidence-based intervention for children with externalizing disorders. This study will contribute to literature aiming to understanding mechanisms of therapist decision-making with respect to evidence-based practice implementation in children’s mental health. If therapist anxious distress is, in fact, causing therapists to avoid using time-out and to deprive parents of an important strategy in mitigating their children’s disruptive behavioral symptoms, results will have important implication for training therapists and improving the quality of care. Using a clinical vignette-based survey design, our primary aim was to identify whether therapists experience anxious distress when implementing time-out in session and whether that anxious distress leads to avoidance of time-out. We hypothesized that anxious distress would rise as time-out progresses and that higher levels of therapist anxious distress would lead to higher likelihood of avoiding time-out. Exploratory analyses will identify predictors of time-out avoidance by examining whether time-out avoidance varies as a function of client factors (a history of maltreatment vs no history of maltreatment) and therapist professional factors (i.e., BPT training, years of practice).

Methods

Participants

Participants (N = 198) included mental health professionals who had seen a child or adolescent client up to 2 months prior to completing the survey. Participants had the option to skip questions, or select N/A for certain questions. Due to these options, there was slight variability about which were included in each analysis (range 169–190 participants). The participants identified their primary work setting as being a private practice (34.5%) or community agency (31.6%). 89.9% of participants describe working with children as a major part of their work, with the remaining 10.1% describing it as a minor part of their work. Roughly 85.3% of recruited mental health professionals reported having a master’s degree and 61.8% reported prior BPT training. Participants reported using time-out with 49.9% of young children with behavioral disorders who present to their practices (SD = 32.38), with other interventions being more commonly used (e.g. positive parenting strategies, relaxation techniques, and feeling identification). Nine participants reported never using time-out. Reported average years of practice as a therapist was 9.6 years (SD = 8.6). See Table 1 for additional participant characteristics.

Procedures

Participants were recruited through emails sent to child and adolescent mental health professional listservs across the US and recruitment advertisements on child and adolescent mental health professional social media groups. Participants completed a 20-min anonymous Qualtrics survey in which they were eligible to consent to the study if they reported that they had seen a child or adolescent client in the last two months. Upon consent, participants were randomly assigned to one of two versions of a three-part clinical vignette in which the reason for a family referral to treatment was varied: (1) a family was referred to treatment due to child externalizing behaviors or (2) a family was referred to treatment due to a history of maltreatment by the caregiver. Throughout both versions of the vignette the child presents with externalizing behaviors in session and the therapist coaches the caregiver to administer a time-out to the child in response to defiance. Participant received a $10 incentive upon survey completion. All study procedures were deemed exempt by the University of California Santa Barbara and National Association of Social Workers Institutional Review Boards.

Clinical Vignette

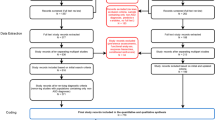

Therapists read one of two versions of a clinical vignette of a typical early time-out session a therapist might deliver within treatment for disruptive or externalizing behaviors. The only difference between the versions was the reason for referral (i.e., the presence or absence of a history of maltreatment by the caregiver). The vignette was divided into three parts (hereafter referred to as “time points”). Throughout the three-part clinical vignette, survey respondents were asked to imagine that they were coaching the caregiver in the delivery of time-out and to rate their personal level of distress and avoidance (likelihood of abandoning the time-out or not delivering it in the future) if the situation were occurring. The first portion (“time one”) of the three-part vignette described a scenario in which the therapist introduces time-out to the caregiver by coaching the caregiver to bring the child to the time-out chair because the child ignored the caregiver’s command. During this part of the vignette, the caregiver seems hesitant and resistant to utilizing time-out with her child and the child is evading his mother’s attempts to put him in the time-out chair. Next (“time two”), the caregiver guides the child to the time-out chair and the child’s disruptive behaviors worsen. The caregiver is later coached to leave the room with the toys. The child’s disruptive behaviors escalate further, and he prevents his mother from leaving the room. In the final part of the clinical vignette (“time three”), the caregiver leaves the room, and the child continues to cry and plead, but eventually stops. The caregiver is then coached to continue with the time-out sequence and the vignette ends with the child listening and following directions, despite being upset. See Fig. 1 for a detailed flow chart of the clinical vignette.

Measures

Participant Characteristics

Participants were asked to provide demographic information, including age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, and employment. Employment information included items that inquired about the mental health professionals’ training, years practiced, employment setting, populations served, and therapeutic strategies utilized.

Anxious Distress During Time-Out Implementation

At each time point of the clinical vignette, after the scenario was presented, participants were instructed to imagine themselves as the therapist and asked to rate their level of anxious distress at this point in the clinical encounter on an 11-point Likert-type scale from 0 (totally relaxed) to 10 (highest anxiety/distress that you have ever felt).

Avoidance of Time-Out

Avoidance was measured at each time point. Avoidance during the first two time points of the three-part vignette was measured by asking participants to rate the likelihood that they would continue the time-out sequence with the caregiver and child on a 7-point Likert-type scale from 1 (not at all likely) to 7 (extremely likely). Therapists also had the option to select “N/A (I would not have chosen to use time-out with this family because it is not appropriate)”. Avoidance at time three was measured by asking the participant first to rate the likelihood that they would continue to using time-out with the current family in the future and then the likelihood that they would use time-out with other families in the future on a 7-point Likert-type scale from 1 (not at all likely) to 7 (extremely likely). Higher likelihood of continuing with the time-out sequence indicated lower levels of avoidance.

Time-Out Administration Challenges

To evaluate specific challenges to delivering time-out, participants were asked to describe these challenges in an open-ended item after reading the clinical vignette.

Data Analytic Plan

A mixed method design was utilized, in which both quantitative and qualitative data were collected simultaneously. Qualitative evaluation was secondary to the quantitative assessment (QUAN + qual; [36]). That is, quantitative analyses were utilized to understand therapist distress and how it relates to avoidance of time-out. Qualitative analyses were then used to explore the ways in which anxious distress and avoidance were identified and reported by therapists when describing challenges to delivering time-out through coded open-ended responses.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics, repeated measures ANOVA, and logistic regression models were run to understand differences in reported anxious distress and avoidance at each time point of the three-part clinical scenario and with future families. Avoidance was dichotomized and analyzed using logistic regression models to examine differences among therapists endorsing no avoidance on the Likert scale and therapists endorsing at least some avoidance across time points and with future families. Therapists indicating N/A (I would not have chosen to use time-out with this family because it 1 is not appropriate) were excluded from avoidance analyses. We also ran all models categorizing therapists that reported N/A as demonstrating at least some avoidance and the models revealed the same results. Linear regression models were also run with avoidance measured on a continuous scale in which therapists rated their likelihood of continuing the time-out sequence at each time point. For interpretation purposes, avoidance scores were reverse scored so that higher scores indicated greater avoidance, such that 0 = low avoidance and 6 = high avoidance. Logistic regression analyses were then used to examine predictors of time-out use with future families. Exploratory bivariate correlations were run to investigate associations between previous use of time-out with young children with disruptive behaviors and anxiety and avoidance at each time point.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Of the 198 therapists who responded to the survey, 153 expanded on challenges to implementing time-out with children with disruptive behaviors. Open-ended responses were coded following recommendations for qualitative data analyses in implementation science described by Palinkas et al. [36], and the National Cancer Institute [37]. A coding team of two coders read all open-ended responses and developed a coding manual that included relevant codes. Coders then analyzed the open-ended responses to determine if they met the previously established codes by assigning the responses with a 0 (No) or 1 (Yes) for each code. The authorship team then reviewed the codes and conducted further thematic analysis to identify themes.

Results

Anxious Distress and Avoidance over Time

On average, therapists reported the highest levels of anxious distress at time 2 of the scenario (M = 5.25; SD = 1.88). Levels of therapist anxious distress were lower at time 1 (M = 4.49; SD = 1.88) and were the lowest, on average, at time 3 (M = 2.71; SD = 1.81). A repeated measures ANOVA with a Greenhouse–Geisser correction indicated that therapist-reported levels of anxious distress differed statistically across the three time points of the clinical vignette (F(1.638, 307.984) = 212.266, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis with a Bonferroni adjustment demonstrated that anxious distress ratings significantly differed between time 1 and time 2 (0.762, p < 0.001), time 1 and time 3 (− 1.778, p < 0.001), and time 2 and time 3 (− 2.540, p < 0.001). See Fig. 2 for a visualization of therapist reported anxious distress across the three time points.

At time 1, 24 therapists indicated that they would not have chosen to use time-out at all because they perceived it as inappropriate. At time 2, 26 therapists indicated that they would not have delivered time-out. Of those that did report time-out avoidance levels on the Likert-type scale, reverse-coded time-out avoidance levels ranged from 0 (low avoidance) to 6 (high avoidance) at each timepoint, and were similar across time 1 (M = 2.04; SD = 1.92) and time 2 (M = 2.10; SD = 2.00). Time-out avoidance was lowest at time 3 of the three-part scenario (M = 1.40; SD = 1.72). Repeated measures ANOVA showed that therapist reported levels of time-out avoidance with the family in the clinical scenario across the three time points differed significantly (F(2, 320) = 32.579, p < 0.001). The difference across times 1 and 2 was not significant (0.062, p = 1.000). The difference in time-out avoidance was significant across time 1 and time 3 (− 0.640, p < 0.001), and time 2 and time 3 (− 0.702, p < 0.001). Figure 3 demonstrates therapist reported avoidance across the three time points.

With respect to dichotomized avoidance, at time 1, 44 therapists (25.3%) were not likely to avoid time-out at all and 130 therapists (74.7%) reported at least some avoidance. At time 2, 47 therapists (27.8%) were not likely to avoid time-out and 122 therapists (72.2%) reported at least some avoidance. At time 3, 72 therapists (37.9%) were not likely to avoid using time-out with the same family and other families in the future and 118 therapists (62.1%) reported at least some avoidance using time-out with the same family and other families in the future.

Relationship Between Anxious Distress and Time-Out Avoidance

Table 2 shows results from the logistic regression models that examined the relationship between levels of anxious distress and time-out avoidance (0 = Not likely to avoid; 1 = At least some avoidance) at each time point during the three-part clinical scenario. Time 1 anxious distress did not relate to time-out avoidance at time 1 (OR 0.988; 95%CI [0.820, 1.191]), nor did time 2 anxious distress relate to time 2 time-out avoidance (OR 1.017; 95%CI [0.846, 1.222]). However, as anxious distress increased at time 3, therapists were 1.366 times more likely to endorse time-out avoidance when delivering time-out with the same family in the vignette (95%CI [1.135, 1.645]) and 1.445 times more likely to endorse time-out avoidance when delivering time-out with future families (95%CI [1.192, 1.751]).

Table 3 shows the results from the linear regression models that tested the relationship between therapist-reported anxious distress and time-out avoidance, when avoidance was treated continuously. Consistent with the logistic regression models, time 1 anxious distress did not relate to time-out avoidance at time 1 (B = − 0.094, p = 0.264), nor did time 2 anxious distress relate to time 2 time-out avoidance (B = 0.052, p = 0.554). However, higher time 3 anxious distress was associated with greater therapist time-out avoidance when asked about future use of time-out with the same family in the vignette (B = 0.423, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.13, a medium effect) and when delivering time-out with future families (B = 0.4, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.12, a medium effect).

Predictors of Future Time-Out Use

Table 4 presents the results from the logistic regression analyses used to examine predictors of time-out use with future families (0 = Not likely to avoid; 1 = At least some avoidance). Prior BPT training was associated with less time-out avoidance with future families (OR 0.260, 95%CI [0.128, 0.530]). Presence or absence of a history of maltreatment in the clinical vignette (95%CI [0.598, 2.155]) and number of year practicing (95%CI [0.980, 1.057]) did not relate to therapist reported use of time-out with future families.

Previous Therapist Time-Out Use and Current Anxious Distress and Avoidance

Table 5 presents bivariate correlations used to investigate the relationship between previous time-out use by therapists in their practices and anxious distress and avoidance in the current vignette. The percent of young children with disruptive behaviors with whom therapists report using time-out was significantly correlated with anxious distress at time 3, and avoidance at each timepoint. Use of time-out with a higher percentage of clients was associated with lower anxious distress at time 3, and lower avoidance at each timepoint.

Qualitative Results

Therapists described multiple challenges to delivering time-out with youth with disruptive behaviors. Challenges reported fell into four primary themes, including time-out eliciting too much distress in the parent or child, time-out eliciting anxiety/distress in the therapist, time-out being difficult to implement with consistency and follow-through, and time-out being ineffective. Themes are described below and additional illustrative quotes are found in Table 6.

Many of the responses provided by therapists highlighted a concern about parent or child distress, with therapists explaining that time-out is “distressing to children, distressing to parents.” Regarding caregiver distress specifically, therapists stated that “parents not being able to stay regulated and calm,” and “parent fear” are both challenges to implementing time-out. Regarding children, they described that “time-out provokes more distress than many young children can bear.” In addition to frequently reporting that one of the primary challenges to delivering time-out is the caregivers’ and child’s distress, respondents described their (the therapists’) own distress as an obstacle to implementation. One described it challenging to “coach the parent in a calm, confident manner,” and others described time-out as “causing serious distress for all parties involved.” Another explained that they struggled to “tolerate how much distress [time-out] would cause in the clients and their parents.”

Therapists also reported that time-out is difficult to implement, due to challenges to “parents maintaining consistency and committing the time to proper use, [and] the parents’ ability to follow through in an appropriate manner.” Many therapists described challenges to parental consistency and practical difficulties to getting the child into time-out, and difficulties “convincing parents who have tried time-out before that it could be more effective if it is practiced differently.” Therapists also described their own beliefs about time-out being ineffective, reporting, for example, that “it’s not effective for long term behavioral change and leads to power struggles between parents and children.”

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate therapist anxious distress implementing time-out and avoidance of implementing time-out, and to further understand challenges to its implementation. Results of this study indicate that, as was hypothesized, anxious distress increased as the time-out progressed, but decreased at its resolution. Regarding whether therapist anxious distress is associated with time-out avoidance, findings both confirmed and disconfirmed aspects of this hypothesis. Higher anxious distress during the time-out delivery (at time 2) did not increase the likelihood of abandoning the time-out midway, in contrast with the study’s hypothesis. However, higher anxious distress at the time-out’s resolution (time 3) predicted a higher likelihood of avoiding time-out in the future with both the same client and with other clients.

These findings are aligned with research indicating that therapist anxiety contributes to drift from evidence-based interventions [17], and adds implementation insights related to working with young children to literature that has primarily focused on interventions for adults. The findings also suggest that therapist anxious distress may not lead to premature termination of a time-out midway through, but that if the therapist’s anxious distress does not adequately resolve at the time-out’s end, their decisions about future use of the EBI may be impacted. Interestingly, the clinical vignette ends with a successful time-out, in which the child complies with the parent’s request. Despite the successful resolution, 62.1% of therapists reported at least some avoidance of using time-out in the future. Although this likelihood of avoidance decreased from time points 1 and 2 of the vignette, it remains high, suggesting that even experiencing a successful time-out delivery and resolution may not mitigate the impact a therapist’s anxious distress has on their future treatment decisions. It would be interesting to know what would decrease the likelihood of avoidance, if not a successful in-session time-out delivery. Given that prior BPT training was associated with lower avoidance in the current study, it is possible that greater understanding of the purpose of time-out, its theoretical justification, or more experiences of using it successfully may mitigate anxious distress or the impulse to abandon the intervention. In fact, the associations found in exploratory analyses between higher therapist use of time-out in their practices and reported lower anxious distress and avoidance in the clinical vignettes provides initial evidence that more experience with the procedure may mitigate the impulse to abandon it.

Qualitative findings expanded on quantitative results in this study, providing insight into particular challenges therapists experience that may contribute to their own anxious distress and subsequent avoidance of delivering time-out. Specifically, therapists described their own fears and discomfort delivering time-out, with particular focus on the distress it could cause the caregiver or child. They perceived the intervention to be ineffective and difficult to implement in practical ways, as well. These findings further indicate that a greater understanding of the procedure, including how to implement it successfully, its theoretical justification, and outcomes for families and children, may decrease therapist distress and increase effective implementation. These findings also point to the importance of preparing clinicians in advance for how to emotionally regulate common affective responses to implementing time-out. Future research on implementation strategies could investigate the impact of both didactic training addressing theory, justification, and procedures, and experiential training on therapist perceptions and uptake of time-out.

Given that therapist anxious distress at time point 3 increased the likelihood of avoiding time-out in the future, addressing therapist anxious distress during and after an intervention may improve clinical decision-making. Therapists should potentially be trained specifically to manage their own anxious distress during treatment. In fact, developing implementation interventions that address therapist distress, such as helping therapists learn to manage their own anxious reactions, has been recommended [14, 38]. A recent study found that 12 therapists who underwent experiential training reported improved attitudes towards exposure, one underused EBI [39]. While this intervention did not specifically evaluate therapist anxiety, experiential training may have decreased therapist anxiety, leading to more positive attitudes towards the practice. Therapist anxiety sensitivity has also been found to predict lower clinical proficiency in delivering exposure therapy [40]. In Harned and colleagues’ study, therapists who reported higher fear of anxious sensations at baseline demonstrated lower proficiency in delivering exposure therapy after receiving training in it. It was hypothesized that these therapists may have engaged in more anxiety-mitigating strategies during delivery, in an attempt to alleviate their and their client’s discomfort. Unfortunately, these strategies render the intervention less effective. Therapist concerns referenced in open-ended responses in the current study, describing worry about the client’s or one’s own distress, may reflect a similar fear of eliciting temporarily distressing sensations. Therapists whose anxious distress contributes to time-out avoidance, as well as those whose anxiety-sensitivity contributes to hesitant and less effective service-delivery may benefit from trainings that specifically teach them to manage their own anxiety during treatment delivery.

The present study was limited in that it relied on therapist self-report. Outcomes were evaluated based on therapist reports about hypothetical behaviors and avoidance, which may or may not closely approximate their in-session actions. It may be challenging to accurately measure avoidance, given that practitioners may be hesitant to admit that they would avoid engaging in a best-practice, particularly if their avoidance is based on anxious distress. For this reason, we measured intention to use time-out, which we believed clinicians would report more honestly, and used the reverse score as a measure of avoidance. Strength of intention to use a practice is frequently used in implementation research [41]. Previous research has found that strength of reported intention to use an evidence-based practice does predict subsequent use of that practice. In one study, teachers who reported a strong intention to use a practice were 5.2 times more likely to actually use the practice than teachers who had weak intentions to use them [42]. Additionally, similar ratings of intention to use a practice have been used in previous studies, and such scales have been found to be predictive of subsequent clinician behavior (i.e. use of specified EBI) [43, 44]. Despite these efforts to measure avoidance as accurately as possible, future research would benefit from live observations of time-out delivery, or from other methods of assessing in-session behavior, such as review of clinical documentation or ecological momentary assessment (EMA), which could capture self-reports throughout the week as therapists go about delivering services [45]. EMA gathered during time-out delivery in practice would provide real-time insight into therapists’ anxious distress and desire to abandon implementation while circumventing the inaccuracy or recall or imagined vignettes.

Additional limitations include that this study did not gather information about therapist current caseload; although the study asked therapists to consider a specific vignette-based case, it is possible that caseload or setting may impact decisions about whether to use time-out with clients or not. A final limitation in this study was the potential conflation of the terms anxiety and distress when asking therapists to report how they were feeling during the vignette. Although the scale went from “totally relaxed” to “highest anxiety/distress that you have ever felt,” it is possible that therapists interpreted this scale in different ways, with some feeling worried about how the time-out would go, and others finding it upsetting for other reasons. At the same time, distress is often used as a term in the anxiety treatment literature to assess perceptions of anxiety and distress in given situations, as in Subjective Units of Distress (SUDS). It would be beneficial to understand more about the specific physiological sensations and cognitions therapists envisioned when reporting on their anxious distress, to confirm the cause of any subsequent avoidance. By collecting qualitative responses, we have begun to disentangle specific therapist concerns and reactions to delivering time-out, however the nature of their anxious distress should be further investigated. Despite its limitations, this study provides initial insight into an important factor shaping the implementation of an important EBI for young children; teaching caregivers to safely and effectively use time-out.

Despite limitations, this article contributes to a more robust understanding of treatment fidelity and clinical decision-making. Prior research on how therapist factors impact EBI implementation has focused on therapist attitudes, beliefs, and self-efficacy. Few studies have specifically investigated therapist subjective reports of experiencing anxious distress while delivering an intervention, and how this may impact their decision-making. Since time-out can be a particularly challenging intervention to implement and teach, and is currently the focus of much public discourse in the parenting community [27, 32], it is a useful EBI to investigate. While researchers have attempted to understand controversy about time-out [27, 46], this is the first to explore therapist subjective experiences of anxious distress while delivering the intervention. Attending to systemic factors that impact the implementation of EBIs, such as training, leadership, and agency culture, as well as client factors, is important, considering therapist anxious distress may further support the implementation and delivery of EBIs, and help ensure that clients are receiving clinically-indicated evidence-based care. It will be important to develop implementation interventions specifically addressing therapist anxious distress in the future.

Summary

Many leading evidence-based interventions (EBIs) in psychosocial treatment are complex. One understudied factor that contributes to the underuse of complex EBIs is a therapist’s own anxious distress, particularly regarding EBI components that elicit temporary distress in the client (e.g., exposure therapy for anxiety, time-out for externalizing disorders). Therapist anxious distress may lead to avoidance of the EBI, impeding implementation. Therapist anxious distress when delivering child mental health treatment may contribute to the underuse of some evidence-based interventions, such as time-out for children with disruptive behaviors. This study investigated therapist anxious distress and avoidance related to coaching caregivers to use time-out using a three-part, vignette-based survey design. Therapists (n = 198) read a vignette describing a time-out. At three different points throughout the vignette, therapists reported on their personal anxious distress via Subjective Units of Distress (SUDS) and their likelihood of discontinuing the implementation of time-out in session. Binomial logistic regression analyses examined the relationship between self-reported anxious distress at all 3 time points and likelihood of avoiding time-out to test the hypothesis that elevated anxious distress would be related to higher likelihood of avoiding time-out. Therapists were also asked about challenges to delivering time-out. Open-ended responses were thematically analyzed to further understand avoidance of time-out. Therapists reported moderate levels of anxiety at time points 1 (M = 4.49; SD = 1.88) and 2 (M = 5.25; SD = 1.88) and lower levels of anxiety at time 3 when the time-out had resolved (M = 2.71; SD = 1.81). Most therapists endorsed at least some avoidance of (likelihood of discontinuing) time-out at time 1 (n = 130, 74.7%) time 2 (n = 122, 72.2%), and time 3 (n = 118, 62.1%). Binomial logistic regression analyses at each time point indicated that increased anxious distress corresponded with an increased probability of avoiding time-out delivery only at time point 3 with the current family in the future (OR 1.366; 95%CI [1.135, 1.645]) and other families in the future (OR 1.445; 95%CI [1.192, 1.751]). Qualitative reports expanded on challenges therapists perceived to implementing time-out, including their own distress, the child or parents’ distress, difficulties with parental consistency, and perceiving time-out as ineffective. Findings suggest the potential utility of directly addressing therapist anxiety when providing training and consultation in certain complex EBIs.

Data Availability

The open-ended responses generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available to protect the identities of participants, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Becker-Haimes EM, Okamura KH, Wolk CB, Rubin R, Evans AC, Beidas RS (2017) Predictors of clinician use of exposure therapy in community mental health settings. J Anxiety Disord 49:88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JANXDIS.2017.04.002

Beidas RS, Williams NJ, Becker-Haimes EM, Aarons GA, Barg FK, Evans AC, Jackson K, Jones D, Hadley T, Hoagwood K, Marcus SC, Neimark G, Rubin RM, Schoenwald SK, Adams DR, Walsh LM, Zentgraf K, Mandell DS (2019) A repeated cross-sectional study of clinicians’ use of psychotherapy techniques during 5 years of a system-wide effort to implement evidence-based practices in Philadelphia. Implement Sci 14(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13012-019-0912-4/TABLES/3

Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SMC (2011) Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res 38(1):4–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7

Stadnick NA, Lau AS, Barnett M, Regan J, Aarons GA, Brookman-Frazee L (2018) Comparing agency leader and therapist perspectives on evidence-based practices: associations with individual and organizational factors in a mental health system-driven implementation effort. Adm Policy Ment Health 45(3):447–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10488-017-0835-9

Barnett M, Brookman-Frazee L, Regan J, Saifan D, Stadnick N, Lau A (2017) How intervention and implementation characteristics relate to community therapists’ attitudes toward evidence-based practices: a mixed methods study. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res 44(6):824–837. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-017-0795-0

Beidas RS, Edmunds J, Ditty M, Watkins J, Walsh L, Marcus S, Kendall P (2014) Are inner context factors related to implementation outcomes in cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth anxiety? Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res 41(6):788–799. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10488-013-0529-X/TABLES/3

Powell BJ, Mandell DS, Hadley TR, Rubin RM, Evans AC, Hurford MO, Beidas RS (2017) Are general and strategic measures of organizational context and leadership associated with knowledge and attitudes toward evidence-based practices in public behavioral health settings? A cross-sectional observational study. Implement Sci 12(1):64. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13012-017-0593-9/TABLES/3

Becker-Haimes EM, Williams NJ, Okamura KH, Beidas RS (2019) Interactions between clinician and organizational characteristics to predict cognitive-behavioral and psychodynamic therapy use. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res 46(6):701–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10488-019-00959-6/METRICS

Aarons GA (2005) Measuring provider attitudes toward evidence-based practice: consideration of organizational context and individual differences. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 14(2):255–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.008

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC (2009) Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 4(1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

Shapiro CJ, MacDonell KW, Moran M (2021) Provider self-efficacy in delivering evidence-based psychosocial interventions: a scoping review. Implement Res Pract 2:263348952098825. https://doi.org/10.1177/2633489520988258

Frank HE, Becker-Haimes EM, Kendall PC (2020) Therapist training in evidence-based interventions for mental health: a systematic review of training approaches and outcomes. Clin Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12330

Jensen-Doss A, Haimes EMB, Smith AM, Lyon AR, Lewis CC, Stanick CF, Hawley KM (2018) Monitoring treatment progress and providing feedback is viewed favorably but rarely used in practice. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res 45(1):48–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0763-0

Becker-Haimes EM, Klein CC, Frank HE, Oquendo MA, Jager-Hyman S, Brown GK, Brady M, Barnett ML (2022) Clinician maladaptive anxious avoidance in the context of implementation of evidence-based interventions: a commentary. Front Health Serv. https://doi.org/10.3389/FRHS.2022.833214

Levita L, Salas Duhne PG, Girling C, Waller G (2016) Facets of clinicians’ anxiety and the delivery of cognitive behavioral therapy. Behav Res Ther 77:157–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BRAT.2015.12.015

Mulkens S, de Vos C, de Graaff A, Waller G (2018) To deliver or not to deliver cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders: replication and extension of our understanding of why therapists fail to do what they should do. Behav Res Ther 106:57–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.05.004

Speers AJH, Bhullar N, Cosh S, Wootton BM (2022) Correlates of therapist drift in psychological practice: a systematic review of therapist characteristics. Clin Psychol Rev 93:102132. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CPR.2022.102132

Turner H, Tatham M, Lant M, Mountford VA, Waller G (2014) Clinicians’ concerns about delivering cognitive-behavioural therapy for eating disorders. Behav Res Ther 57:38–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.003

de Jong R, Lommen MJJ, van Hout WJPJ, de Jong PJ, Nauta MH (2020) Therapists’ characteristics associated with the (non-)use of exposure in the treatment of anxiety disorders in youth: a survey among Dutch-speaking mental health practitioners. J Anxiety Disord 73:102230. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JANXDIS.2020.102230

Deacon BJ, Farrell NR, Kemp JJ, Dixon LJ, Sy JT, Zhang AR, McGrath PB (2013) Assessing therapist reservations about exposure therapy for anxiety disorders: the therapist beliefs about exposure scale. J Anxiety Disord 27(8):772–780. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JANXDIS.2013.04.006

Scherr SR, Herbert JD, Forman EM (2015) The role of therapist experiential avoidance in predicting therapist preference for exposure treatment for OCD. J Contextual Behav Sci 4(1):21–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCBS.2014.12.002

LoParo D, Florez IA, Valentine N, Lamis DA (2019) Associations of suicide prevention trainings with practices and confidence among clinicians at community mental health centers. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav 49(4):1148–1156. https://doi.org/10.1111/SLTB.12498

Roush JF, Brown SL, Jahn DR, Mitchell SM, Taylor NJ, Quinnett P, Ries R (2018) Mental health professionals’ suicide risk assessment and management practices. Crisis 39(1):55–64. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/A000478

Kaminski JW, Claussen AH (2017) Evidence base update for psychosocial treatments for disruptive behaviors in children. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 46(4):477–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2017.1310044

Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL (2009) Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. J Consult Clin Psychol 77(3):566–579

Wyatt Kaminski J, Valle LA, Filene JH, Boyle CL (2008) A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. J Abnorm Child Psychol 36(4):567–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10802-007-9201-9/TABLES/7

Dadds MR, Tully LA (2019) What is it to discipline a child: what should it be? A reanalysis of time-out from the perspective of child mental health, attachment, and trauma. Am Psychol 74(7):794–808. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000449

Eyberg S (1988) Parent-child interaction therapy. Child Fam Behav Ther 10(1):33–46. https://doi.org/10.1300/J019v10n01_04

Shanley JR, Niec LN (2010) Coaching parents to change: the impact of in vivo feedback on parents’ acquisition of skills. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 39(2):282–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410903532627

Brookman-Frazee L, Stadnick NA, Lind T, Roesch S, Terrones L, Barnett ML, Regan J, Kennedy CA, Garland FA, Lau AS (2021) Therapist-observer concordance in ratings of EBP strategy delivery: challenges and targeted directions in pursuing pragmatic measurement in children’s mental health services. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res 48(1):155–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10488-020-01054-X

Woodfield MJ, Cargo T, Barnett D, Lambie I (2020) Understanding New Zealand therapist experiences of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) training and implementation, and how these compare internationally. Child Youth Serv Rev 119:105681. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHILDYOUTH.2020.105681

Morawska A, Sanders M (2011) Parental use of time out revisited: a useful or harmful parenting strategy? J Child Fam Stud 20:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-010-9371-x

Quetsch LB, Nancy Wallace MM, Amy Herschell MD, McNeil CB (2015) Weighing in on the time-out controversy. An empirical perspective. Clin Psychol 68(2):4–19

Woodfield MJ, Cargo T, Merry SN, Hetrick SE (2021) Barriers to clinician implementation of parent-child interaction therapy (Pcit) in new zealand and australia: what role for time-out? Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(24):13116. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH182413116/S1

Woodfield MJ, Brodd I, Hetrick SE (2022) Time-out with young children: a parent-child interaction therapy (PCIT) practitioner review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(1):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH19010145/S1

Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Horwitz S, Chamberlain P, Hurlburt M, Landsverk J (2011) Mixed method designs in implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res 38(1):44–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0314-z

Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute (2018) Qualitative methods in implementation science [White paper]. Retrieved from https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/sites/default/files/2020-09/nci-dccps-implementationscience-whitepaper.pdf

Pittig A, Kotter R, Hoyer J (2019) The struggle of behavioral therapists with exposure: self-reported practicability, negative beliefs, and therapist distress about exposure-based interventions. Behav Ther 50:353–366

Frank HE, Rifkin LS, Sheehan K, Becker-Haimes EM, Crane ME, Phillips KE, Palitz Buinewicz SA, Kemp J, Benito K, Kendall PC (2023) Therapist perceptions of experiential training for exposure therapy. Behav Cogn Psychother 51:214–229. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465822000728

Harned MS, Dimeff LA, Woodcock EA, Contreras I (2013) Predicting adoption of exposure therapy in a randomized controlled dissemination trial. J Anxiety Disord 27(8):754–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JANXDIS.2013.02.006

Wolk CB, Becker-Haimes EM, Fishman J, Affrunti NW, Mandell DS, Creed TA (2019) Variability in clinician intentions to implement specific cognitive-behavioral therapy components. BMC Psychiatry 19(1):1–7

Fishman J, Beidas R, Reisinger E, Mandell DS (2018) The utility of measuring intentions to use best practices: a longitudinal study among teachers supporting students with autism. J Sch Health 88(5):388–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/JOSH.12618

Godin G, Belanger-Gravel A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J (2008) Healthcare professionals’ intentions and behaviours: a systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implement Sci 3(36):1–12

Presseau J, Johnston M, Francis JJ, Hrisos S, Stamp E, Steen N et al (2014) Theory based predictors of multiple clinician behaviors in the management of diabetes. J Behav Med 37(4):607–620

Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR (2008) Ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 4:1–32. https://doi.org/10.1146/ANNUREV.CLINPSY.3.022806.091415/CITE/REFWORKS

Canning MG, Jugovac S, Pasalich DS (2021) An updated account on parents’ use of and attitudes towards time-Out. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 54:436–449

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Quantitative data analysis was conducted by HS. Integration of qualitative and quantitative findings was performed by all authors. All authors drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

This study was reviewed and determined exempt by the University of California, Santa Barbara Internal Review Board.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Klein, C.C., Salem, H., Becker-Haimes, E.M. et al. Therapist Anxious Distress and Avoidance of Implementing Time-Out. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-024-01706-1

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-024-01706-1