Abstract

This study investigated how youth attachment anxiety and avoidance are associated with informant discrepancies of intrafamilial aggression within families where youth have clinically significant mental health challenges (N = 510 youth–parent dyads). Using polynomial regressions, we tested whether youth attachment avoidance and anxiety moderated the absolute magnitude of the association between youth- and parent-reports of aggression toward each other. Furthermore, difference scores were computed to test whether youth attachment was associated with the direction of youths’ reports of the frequency of aggression relative to parents (i.e., did youth under- or over-report). Dyads’ reports of youth-to-parent aggression were more strongly related at high than low levels of attachment anxiety. Results also revealed that youth attachment anxiety was associated with youth over-reporting of youth-to-parent and parent-to-youth aggression (relative to parents), whereas attachment avoidance was associated with youth over-reporting parent-to-youth aggression (relative to parents). These findings highlight the importance of understanding the source of informant discrepancies in social-emotional development and family functioning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The nature of people’s attachments with their primary caregivers is widely believed to shape their perceptions, interpretations, and responses to interpersonal behavior [1]. Different attachment styles may generate specific types of biases that influence social interactions. For example, individuals high in attachment anxiety appear to be better able to retrieve negative memories [2,3,4]. These attachment-related biases tend to be most pronounced during stressful conflicts with attachment figures [5]. Conflict between parents and youth are one such type of interaction that family members may perceive in diverging manners, depending on their attachment styles [6, 7]. Furthermore, unlike other outcomes (e.g., youth depression) for which discrepancies can be subject to contextual differences stemming from observing someone in different environments (e.g., at home versus at school), overt aggression between family members is not subject to these contextual effects as it is presumed to be equally visible to both informants. Yet, relatively little attention has been paid to the meaning of discrepancies between parents and youth in this domain.

The present study sought to address the gap in this literature by examining how youth attachment anxiety and avoidance related to the discrepancies between youth and parent reports of youth aggression toward parents as well as parent aggression toward youth. We examined these discrepancies from two perspectives: first, in terms of their magnitude—i.e., how strongly do parents and youth (dis)agree—and second, in terms directional differences—i.e., under what conditions do adolescents under- or over-report aggression, relative to their parents. Understanding the magnitude and direction of systematic discrepancies between youth and parent reports may hold important implications for researchers—who, for instance, may seek to understand diverging findings across informants—as well as clinicians—who, for example, may be interested in addressing discrepant perspectives about intrafamilial violence as a starting point for therapy.

Attachment Anxiety and Avoidance

Youth high in attachment insecurity (e.g., attachment anxiety or avoidance) are unlikely to expect parents to respond with sensitivity to their bids for a safe haven and secure base when called upon during periods of stress and challenge [8]. Attachment anxiety involves the overactivation of the attachment system and is associated with worrying that others will not be responsive in times of needs and thus the escalated expression of one’s attachment needs [9, 10]. Conversely, attachment avoidance involves a deactivation of the attachment system and is associated with masking or muting the expression of one’s attachment needs [10]. As these forms of attachment insecurity are associated with the distorted expression of attachment needs, they may “miscue” others who in turn respond in ways that perpetuate the cycle of insecurity, locking family members into non-productive and conflictual interaction patterns. In contrast, attachment security is associated with the clear communication of attachment needs and thus promotes a shared understanding of interpersonal intentions and interactions, increasing the likelihood of sensitive responsiveness [11, 12].

Attachment Insecurity and Perceptions of Interpersonal Conflict and Aggression

Research examining attachment-related biases among youth in their reporting of their own and others’ aggressive behavior is limited. Some studies have found that youth attachment security is related to more agreement between parent and youth reports of conflict and externalizing problems [13,14,15], but few have examined the unique ways that attachment anxiety and avoidance influence such biases. Among the few, Berger et al. [13] found that attachment anxiety was associated with greater absolute discrepancies (i.e., disagreements in either direction) between youth and parent reports of youth externalizing problems. They also found attachment anxiety was related to youths reporting higher levels of externalizing problems relative to their parents’ reports. Conversely, adolescent attachment avoidance was related to lower levels of absolute agreement between youth and mother (but not father) reports, and no directional differences in reporting higher or lower levels of symptoms than their parents.

Among adults, attachment insecurity has been associated with more disagreement between romantic partners’ reports of conflict in their relationship. For example, Campbell et al. [16] found that anxiously attached partners overreported the frequency and severity of relationship conflict, compared with their romantic partner. In another study, Overall et al. [17] found that participants’ attachment avoidance was associated with overreporting how intense their partners’ negative emotions were during conflict discussions. Similarly, Ehrlich et al. [18] found that attachment security was associated with smaller discrepancies in couples’ reports of marital conflict. In sum, extant studies appear to indicate that attachment anxiety and avoidance are related to greater discrepancies between informants. Furthermore, these findings suggest that attachment anxiety is generally associated with over-reporting one’s own externalizing and conflict behavior, whereas attachment avoidance is linked to over-reporting others’ negative emotional responding, which may generalize to aggressive behaviors.

Statistical Approaches to Assessing Informant Discrepancies

In recent years, investigations on informant discrepancies have garnered increased attention and employed more advanced analytic approaches such as polynomial regression (see [19]). Polynomial regression allows researchers to test whether scores from one reporter increase or decrease in a stepwise manner with scores from a second reporter. Unlike most other tests of informant discrepancies, it allows for testing whether this relation follows a linear or higher-order function (e.g., quadratic, cubic, [20]). Polynomial regression analyses have increasingly been used in clinical psychology to understand the factors that are associated with discrepancies between parent–youth reports, for example by examining how disorganized attachment is associated with discrepancies between youth and parent reports of youths’ internalizing and externalizing symptoms [14]. Here, we employed polynomial regression analyses to investigate whether youth attachment anxiety and avoidance moderate the magnitude of the association between youth and parent reports of aggressive behaviors.

In addition to our polynomial regression analyses, we also examined whether youth anxiety and avoidance were related to youth under- or over-reporting instances of aggression, compared with parent reports, via difference scores. These have long been used to assess directional differences between parent and children reports of various constructs (e.g., [13]). Difference scores add important information beyond polynomial regression analyses because, even though a strong association may exist between reporters (indicating their scores increase or decrease in relation to each other), difference scores can show whether one reporter consistently provides higher or lower estimates than the other. Although most past research has used either polynomial regression or analysis of difference scores, applying both alongside each other provides a unique opportunity to examine both the (1) the magnitude of discrepancies between different reporters on the same construct, and (2) directional differences between reporters, helping to explain why one reporter may systematically provide higher or lower estimates relative to the other. Understanding both types of systematic differences may be valuable for researchers and clinicians when trying to make decisions around which informant type to collect data from, or to make sense of discrepancies in mean levels or covariances between youth and parent reports.

The Present Study

The aim of the present study was to examine whether youth attachment anxiety and avoidance were associated with discrepancies between youth and parent reports of youth-to-parent and parent-to-youth aggression. Using a sample of youth with clinically significant mental health problems and their parents, we examined the magnitude and direction of these discrepancies via two approaches. First, we used polynomial regression analyses to investigate whether youth attachment anxiety and avoidance moderated the magnitude of the relation between youth and parent reports of intrafamilial aggression. Second, in analyses using difference scores, we tested whether youth attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were associated with the direction of their reports on intrafamilial aggression (i.e., did youth under- or over-report) relative to their parents. Unlike previous studies, informants provided ratings on behaviors that only occur between the informants (i.e., aggression between youth and their parents), thus informant discrepancies could not be attributed to domain differences (e.g., observing youth at home versus school). In terms of absolute discrepancies, we expected that youth attachment anxiety and avoidance would be related to greater discrepancies between youth and parent reports of aggression in their relationship. In terms of directional differences, based on prior research, we expected attachment anxiety to be related to youth over-reporting of youth-to-parent aggression (relative to their parents’ reports), whereas we expected attachment avoidance to be related to youth over-reporting of parent-to-youth aggression (relative to their parents’ reports). We did not have specific hypotheses about how high attachment anxiety would relate to directional differences in youth reports of parent-to-youth aggression, or how attachment avoidance would relate to directional differences in youth reports of youth-to-parent aggression, as the findings on these relations have been less clear.

Method

Participants and Procedure

We obtained ethics approval for this study from the Research Ethics Board at Simon Fraser University, protocol #2011s0284. Participants were 510 birth parents (Mage = 42.64 years, SD = 6.86, range = 27.00–65.00; 86% mothers) and their children (Mage = 13.96 years, SD = 2.36, range = 7.34–19.04; 56.1% female) referred by community mental health centers, schools, and hospitals to participate in a parenting intervention for caregivers of youth with severe emotional and behavioral difficulties (i.e., the Connect Parenting Program). Parents reported on their ethnicity (74.7% White; 11.4% Indigenous; 7.1% Asian; 3.9% “other ethnicity”) as did their youth (65.1% White; 15.2% Indigenous; 5.7% Asian; 8.6% “other” ethnicities). Data for this study consisted of baseline assessments prior to treatment. Exclusion criteria for this study included low cognitive functioning, severe psychopathology (e.g., psychosis), and low fluency in English. In cases where both parents of youth participated in the research (N = 7), maternal reports were retained to avoid dependencies in the data. Consent to participate was provided by parents and assent by youth.

Measures

Intrafamilial Aggression. Participants completed the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-2; [21]), a widely used questionnaire that assesses engagement in physical and psychological aggression. Past research has found support for the psychometric properties of the CTS-2, including good internal consistency, reliability, validity, and factor structure [21,22,23,24]. Due to questionnaire space limitations, we employed a modified version of the CTS-2 to capture perpetration and victimization within the family in the past 6 months. Specifically, parents and their teens reported perpetration and victimization through physical (7 items) and psychological aggression (9 items) using a 4-point scale (1 = Never to 4 = Always). Total scores for perpetration and victimization were computed for parents and youth by summing their responses on items tapping physical and psychological aggression. This procedure yielded scores tapping (1) youth-to-parent aggression reported by youth, (2) youth-to-parent aggression reported by parents, (3) parent-to-youth aggression reported by youth, and (4) parent-to-youth aggression reported by parents. These measures showed good internal reliability in our data for youth reports of their physical (α = 0.84) and psychological (α = 0.86) aggression, as well as their parents’ physical (α = 0.88) and psychological (α = 0.88) aggression. Similarly, good internal reliability was demonstrated in measures of parent reports of their physical (α = 0.73) and psychological (α = 0.82) aggression, as well as youth physical (α = 0.89) and psychological (α = 0.89) aggression. Previous studies using this modified version of the CTS-2 have found similarly strong reliability and validity indices [25, 26].

Attachment Anxiety and Avoidance. Youth completed the Adolescent Attachment Anxiety & Avoidance Inventory (AAAAI; [27]; previously the Comprehensive Adolescent Parent Attachment Inventory), a measure adapted from Brennan et al.’s [28] Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (ECRS). Consistent with other self-report measures of attachment, two super-ordinate factors consistently emerge from this 36-item measure: attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance [27, 29,30,31,32]. In this study, due to questionnaire space limitations, we employed a shortened version of the AAAAI, which included 16 items with the highest factor loadings from the original scale such as “I need a lot of reassurance that I am loved by my parent” (attachment anxiety) and “I try to avoid getting too close to my parent” (attachment avoidance). Items were rated using a 7-point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 7 = Strongly Agree). The scale has shown strong psychometric properties—including clear factor structure and strong convergent validity—in community and clinical samples [30, 33, 34]. Others who have used similar adaptations of the ECRS have also found strong psychometrics [35, 36]. In the present study, internal reliability for attachment anxiety and avoidance measures was strong (αs = 0.83 and 0.90, respectively).

Data Analytic Plan

Polynomial Regression Analyses

Four hierarchical polynomial regression analyses were conducted, each predicting youth-reports of youth or parent aggression from parent-reports of the same aggressive behavior. For each model, parent and youth sex and age were entered into the first step of each regression to control for potential confounds. For each model, the second step included five terms: parent reported aggression, youth attachment anxiety or avoidance, the two aforementioned terms squared, and the interaction term between parent-reported aggression. In two of the models, youth attachment anxiety was included as a predictor in this step and in two other models, youth attachment avoidance was included. The third and final step in the hierarchical regressions included higher order terms. We included the squared terms (in Step 2) to prevent interaction terms from reflecting quadratic effects of informant reports, which is important to consider when one cannot assume informant agreement is strictly linear (see [37]). Furthermore, in line with recommendations from Edwards [20], we modeled interactions with these quadratic terms (in Step 3), to avoid underestimating the complexity of associations within our data. Significant and marginally significant interaction terms were interpreted using the Johnson–Neyman (JN) technique [38], which allowed us to identify the values of the moderator (i.e., regions of significance) at which the relation between the predictor and dependent variable is significant. Polynomial regression analyses had sufficient power (0.80) to detect relatively small effects f2 = 0.03, using a two-tailed test with a p value of 0.05—for comparison, Cohen [39] labeled f2 = 0.02 as a small effect and f2 = 0.15 as a medium effect.

Difference Score Analyses Multiple regression analyses were conducted using standardized youth-parent conflict discrepancy scores to examine whether youth attachment anxiety or avoidance was related to aggression under- or over-reporting relative to parents. Like our polynomial analyses, we ran four models, each predicting difference scores for each type of aggression (i.e., youth-to-parent and parent-to-youth) from each type of attachment insecurity (i.e., anxiety and avoidance). In line with guidelines from De Los Reyes and Kazdin [40], difference scores were computed by standardizing all scores and subtracting youth reports from parent reports of aggression. We entered parent and youth sex and age as predictors in Step 1 to control for their potential effects. We entered either attachment anxiety or avoidance in Step 2. Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 25. The data that support all the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations are summarized in Table 1 and show that parents and youth reported slightly higher levels of aggression perpetrated towards them compared to aggression perpetrated by them. Specifically, parent reports of youth-to-parent aggression (M = 3.22, SD = 0.98) exceeded youth reports of their own aggression (M = 2.93, SD = 0.82; t(450) = 6.57, p < 0.001). Similarly, youth reports of parent-to-youth aggression (M = 2.98, SD = 0.97) exceeded parent reports of their own aggression (M = 2.69, SD = 0.55, t(453) = 6.72, p < 0.001). Nonetheless, parent and youth reports of youth-to-parent and parent-to-youth aggression were significantly correlated (r = 0.47, p < 0.001 and r = 0.37, p < 0.001, respectively). Next, we describe the results from our polynomial regression analyses, starting with how attachment anxiety predicts informant discrepancies of youth-to-parent and then parent-to-youth aggression. We then report the next set of analyses, but with youth attachment avoidance. Thereafter, we report the results of parallel analyses using difference scores, presented in the same order as they were for polynomial regression analyses.

Polynomial Regression Analyses

Attachment Anxiety and Youth and Parent Reports of Aggressive Behavior

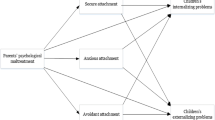

Youth-to-Parent Aggression Results from the hierarchical polynomial regression analyses (see Table 2) showed that parent reports of youth-to-parent aggression significantly predicted youth reports of their own aggressive behavior, as did the quadratic term of parent reports of youth aggression. Youth attachment anxiety, but not its quadratic term, significantly predicted youth reports of youth-to-parent aggression. Key to our predictions, the interaction term between parent report of youth aggression and attachment anxiety was also significant (b = 0.08, SE = 0.03, p = 0.007), but not in our expected direction—the association between parent and youth reports of youth aggression was stronger at higher rather than lower levels of youth attachment anxiety. We illustrated this effect using the interActive plotting utility ([41], see Fig. 1). The Johnson–Neyman technique indicated that the effect of parent reports of youth aggression on youth reports of youth aggression was significant across all values of youth attachment anxiety.

Parent-to-Youth Aggression Results from the hierarchical polynomial regression (see Table 2) showed that parents’ reports of their own aggression and its quadratic term significantly predicted youth reports of parent-to-youth aggression. Youth attachment anxiety, but not its quadratic term, also predicted youth reports of parent-to-youth aggression. The interaction term between parent reports of parent-to-youth aggression and youth attachment anxiety, however, was not significant, indicating that youth attachment anxiety was not related to the strength of agreement between informants on parent-to-youth aggression. Parent and youth age and sex were not significant predictors of youth reports of parent-to-youth aggression.

Attachment Avoidance and Youth and Parent Reports of Aggressive Behavior

Youth-to-Parent Aggression Parent reports of youth-to-parent aggression and its quadratic term significantly predicted youth reports of youth-to-parent aggression (see Table 3). Attachment avoidance also significantly predicted youth reports of youth-to-parent aggression. The squared term of attachment avoidance was not significant, however. The interaction between parent reports of youth aggression and youth attachment avoidance fell below significance (b = − 0.04, SE = 0.02, p = 0.08), but was in the hypothesized direction (i.e., we expected the association between parent and youth reports of youth aggression to be stronger at lower levels of youth attachment avoidance). Parent and youth age and sex were not significant predictors of youth reports of youth-to-parent aggression.

Parent-to-Youth Aggression Parent reports of parent aggression and its quadratic term significantly predicted youth reports of parent aggression (see Table 3). Attachment avoidance was also a significant predictor. The quadratic term of attachment avoidance did not significantly predict youth reports of parent aggression, however. Additionally, the interaction between parent reports of parent aggression and youth attachment avoidance was not significant (b = − 0.09, SE = 0.06, p = 0.11), but was consistent with the direction we predicted (i.e., that youth attachment avoidance would be associated with more informant discrepancies). Youth and parent age and sex were not significant predictors of youth reports of parent-to-youth aggression.

Difference Score Analyses

Attachment Anxiety and Youth and Parent Reports of Aggressive Behavior

Youth-to-Parent Aggression Consistent with prior findings, our results revealed that the effect youth attachment anxiety was significant, with youth reporting higher levels of youth-to-parent aggression relative to parents (b = − 0.100, SE = 0.039, p = 0.011; see Table 4). In terms of control variables, we found youth sex was significant, with girls tending to report higher levels of their aggression relative to their parents (b = − 0.216, SE = 0.100, p = 0.031).

Parent-to-Youth Aggression Findings revealed that the effect of youth attachment anxiety was significant, with youth reporting higher levels of parent-to-youth aggression relative to parents (b = − 0.099, SE = 0.043, p = 0.021; see Table 4). In terms of control variables, only the effect sex was significant, with girls tending to report higher level of parental aggression relative to parents (b = − 0.220, SE = 0.108, p = 0.043).

Attachment Avoidance and Youth and Parent Reports of Aggressive Behavior

Youth-to-Parent Aggression We found no effect of youth attachment avoidance on difference scores of youth-to-parent aggression (p = 0.318; see Table 5). Again, the effect of sex was significant, with girls reporting higher levels of their own aggression relative to their parents (b = − 0.220, SE = 0.100, p = 0.027).

Parent-to-Youth Aggression In line with previous findings, we found that the effect of youth attachment avoidance was significant, with youth reporting more parent-to-youth aggression relative to parents (b = − 0.198, SE = 0.037, p < 0.001; see Table 5). In terms of control variables, we found an effect of gender, with girls tending to report higher levels of parent-to-youth aggression relative to their parents (b = − 0.224, SE = 0.108, p = 0.039).

Discussion

A rapidly growing body of research has highlighted the role of systematic discrepancies between informants, especially parents and youth, when assessing youth social-emotional functioning [42, 43]. With a clinical sample of youth and their parents, the current study sought to examine how two aspects of youth attachment insecurity (anxiety and avoidance) were associated with discrepancies of familial aggression between youth and parents in two ways: first, in terms of the magnitude of their discrepancy, and second, in terms of the direction of their discrepancy (i.e., whether youth under- or over-report relative to parents). Unlike previous studies, parent and adolescent dyads reported on aggression they perpetrated towards each other, meaning that discrepancies between their reports could not be attributed to domain differences (e.g., parents being unable to observe youth aggression at school as well as at home). We hypothesized that higher levels of youth attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance would be related to less absolute agreement on ratings of intrafamilial aggression. We also expected that, relative to parents, youth attachment anxiety would be related to over-reporting their own (i.e., youth-to-parent) aggression, and youth attachment avoidance would be related to over-reporting parents’ (i.e., youth-to-parent) aggression. The findings partially confirmed our hypotheses.

First, in contrast to our hypothesis, we found that youth attachment anxiety was related to more agreement between youth and parent reports of youth aggression toward their parents. One possible explanation is that attachment anxiety, which is characterized by amplified expressions of needs to attachment figures [9], may increase the visible incidents of conflictual interactions between youth and their parents and thereby increase their agreement about conflict in the relationship, particularly when conflict is instigated by youth [44]. In families where youth are high in attachment anxiety, parents and youth may share a heightened cognitive understanding of youth aggressive behavior and attachment needs, but parents may lack the capacities to respond to their adolescents’ needs sensitively. This may explain a relatively high degree of agreement within these dyads, while accounting for the relatively high level of attachment anxiety experienced by youths. Furthermore, we did not find a parallel significant effect for parents’ aggression toward their youth, although the effect was in the same direction (i.e., higher levels of attachment anxiety related to more agreement on parent-to-youth aggression). Here, we examined youth reports of attachment anxiety to their parents in relation to informant discrepancies but did not examine parent reports of youth attachment. Examining whether parents’ reports of youth attachment predict further discrepancies between informants makes for a promising future research question.

Second, we found that the relations between attachment avoidance and discrepancies between youth and parents’ reports of either type of aggression (i.e., youth-to-parent and parent-to-youth) fell below significance. Still, the observed effects were in line with our expected direction which were drawn from prior theory and research showing that attachment avoidance is associated with suppression in the expression of attachment needs. Masked or muted communication of attachment needs could constrict communication and undermine a shared view between youths and parents about the level of conflict in the relationship [44]. One potential explanation for these null findings is that youths’ own attachment avoidance may be systematically related to how they self-report their avoidance—for instance, youth who experience high levels of attachment avoidance may downplay their degree of avoidance, thereby attenuating statistical relations between self-reports of attachment avoidance and informant discrepancies. But it is also conceivable that the effects of attachment avoidance on informant discrepancies are relatively small in magnitude.

Next, moving beyond absolute discrepancies, we found that youth attachment insecurity was also related to the direction of their reports’ discrepancies of intrafamilial aggression relative to their parents. As predicted, we found youth attachment anxiety was related to youth over-reporting their perpetration of aggression toward their parents, relative to their parents’ reports. For youth high in attachment anxiety, their preoccupation with securing their parents attention and love may lead them to ruminate about past aggression toward their parents, consolidating these memories, and potentially exacerbating their perceptions of their misdemeanors toward their parents, deepening their attachment anxiety [4]. In contrast, we found that youth attachment avoidance was related to youth over-reporting their parents’ perpetration of aggression toward them, relative to their parents’ reports. This is not surprising given that attachment avoidance is associated with expectations that others will reject or respond punitively to their expression of attachment needs, thus priming their vigilance and perception of threat in others’ behaviors. These adolescents’ sensitivity to detecting such aggression is likely key in perpetuating their masked or muted expression of their attachment needs. In turn, their parents may lack awareness of the impact of their aggressive behavior on their teens and, consequently, fail to alter their behavior [45].

The current study is unique in multiple ways. First, it involved assessing informant discrepancies of aggression between youth and parents—behaviors both parties would be directly involved in—which allows us to rule out domain differences as a source of informant discrepancies. Second, it brought together the use of hierarchical polynomial regression to examine the magnitude of the association between youth and parent ratings of aggression in relation to attachment anxiety and avoidance, as well as the use of difference scores to explore youth over- versus under-estimation of aggression relative to parent reports. As Berger et al. [13] note, multiple indices are useful in elucidating the nature and scope of attachment related biases. As previously discussed, a stronger or weaker association between youth and parent ratings of aggression does not necessarily preclude youth biases toward under- or overestimation of aggression relative to parent reports. Using linear regressions, we found that youth attachment anxiety was associated with youth reporting higher levels of parent-directed aggression than was reported by their parents. As previously noted, anxious attachment reflects hyperactivation of the attachment system, escalated expression of attachment needs, and an approach-based orientation in relationships. Our results suggest that youth with high attachment anxiety are likely sensitive about their aggression toward their parents, which would undoubtedly trigger even more anxiety [4], leading to higher reports of these behaviors compared to parents. Yet, youth anxiety was not related to youth reporting higher levels of parent-perpetrated aggression than that reported by parents.

In contrast, while youth attachment avoidance was not related to youth reporting higher or lower levels of aggression toward parents (compared to parent reports), avoidance was related to youth reporting higher levels of parent-perpetrated aggression (compared to parent reports). Intriguingly, as previously discussed, attachment avoidance is related to deactivation of the attachment system. Our results are interesting in that they suggest that even though the expression of attachment needs might be muted in youth high in attachment avoidance, they are no less sensitive to and may overestimate parental aggression toward them. Indeed, their sensitivity to detecting such aggression is likely key in perpetuating avoidance and masked expressions of attachment needs. In turn, their parents may lack awareness of the impact of their aggressive behavior on their adolescent and, consequently, fail to alter their behavior [45].

Taken together, these two indices suggest that youth attachment insecurity may introduce both common and unique biases in parent-youth perceptions of aggression. Specifically, attachment anxiety was related to a stronger association between youth and parent reports of youth-to-parent aggression. Furthermore, both youth attachment anxiety and avoidance were related to overestimating youth-to-parent and parent-to-youth aggression, respectively, relative to parents. Importantly, these two sets of findings are congruent with attachment theory and the conceptualization of attachment anxiety versus attachment avoidance.

Clinical Implications

Understanding that parents and youth differ in their reports of parent and youth behaviors is critical to assessing and responding to the clinical needs of families [46]. The source of these discrepancies can range from contextual influences (e.g., ratings based on home or school observation), to the types of information being assessed, and critical affective, cognitive, or interpersonal factors at play. Traditionally, we have viewed divergent reports as a nuisance, clouding our ability to discern an objective truth, and in some instances this is true. Yet recent work has pointed to richness of discrepancies in elucidating the underlying challenges in communication experienced in dyadic or family relationships and the need for tailored clinical approaches [42].

Youth attachment anxiety may present different challenges in youth and/or family therapy than youth attachment avoidance. While youth with attachment anxiety tend to overestimate their aggression toward their parents, our results suggest that the association between youth and parents reports of youth aggression grows stronger as attachment anxiety increases. This shared perspective offers a starting point for exploring the attachment-related meanings of youth aggression in their relationship with parents, and alternative ways that youth might learn to cue their parents about their needs, as well as the importance of sensitive parent responsiveness. Our results regarding youth attachment avoidance were less clear and failed to reach significance, however the directions of our findings were consistent with the view that as youth avoidance increases, youth and parent reports of aggressive behavior increasingly diverge. High attachment avoidance was also related to youth overestimating their parents’ aggression toward them, relative to their parents’ reports. At its core, attachment avoidance represents the tendency to deactivate the attachment system and to distance oneself from others to avoid anticipated rejection or more. As a result, development of a therapeutic relationship with a youth, or within family therapy can be very challenging and must first focus on establishing shared trust and a shared understanding within family communication.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study offers some valuable insight, it is not without limitations. First, our study focused on how youth attachment was associated with informant discrepancies, but did not speak to how parent attachment influences their reporting of intrafamilial violence. Attachment is inherently a relational construct and is best understood through research that adopts a dyadic and transactional framework to understand how interpersonal interactions shape communication and attachment relationships over time. Further research is needed to better understand these processes. Second, the present sample was comprised mostly of mothers (86%), which limits generalizability to father–child relationships. Third, this study examined the role of youth attachment anxiety and avoidance in relation to youth and parent reports of intrafamilial aggression in a sample of families where youth have clinically significant levels of mental health problems. While attachment related biases should be evident in samples where youth exhibit fewer behavioral problems, the magnitude of these effects might be less pronounced because of lower levels of attachment insecurity, intrafamilial aggression, or both. Replications with community samples of families would be needed to evaluate whether these findings generalize beyond families of youth with clinical levels of behavioral problems. Conversely, parents included in our sample had enrolled in a parenting group (but were yet to start the intervention) and may have been more attuned to their children’s emotional or behavioral than parents in comparable situations who did not seek this service. Lastly, the results of our study are correlational, so we cannot rule out the possibility that the informant discrepancies we detected were not caused by factors other than youth–parent attachment insecurity, such as family functioning.

Conclusion

In summary, this study provided new insights into how youth attachment insecurity is associated with discrepancies in youth versus parent reports of intrafamilial aggression using a clinical sample. These findings demonstrate that some of these discrepancies are systematically related to youth attachment insecurity. We found that high levels of youth attachment anxiety were associated with fewer absolute discrepancies between parent and youth reports of youth-to-parent aggression. We also found that youth attachment anxiety was associated with youth over-reporting youth-to-parent aggression (relative to parents), whereas attachment avoidance was associated with youth over-reporting parent-to-youth aggression (relative to parents). Our findings suggest that service providers ought to consider adolescents’ attachment with their caregivers to contextualize potentially systematic discrepancies between youth and other informants when assessing and evaluating the progress of their youth clients.

Summary

A growing body of research on youth social-emotional development has highlighted the importance of understanding the systematic sources of discrepancies between informants, especially parents and youth. In this study, we investigated whether youth attachment anxiety and avoidance were associated with discrepancies between parents and youth with clinically significant levels of mental health problems (N = 510 dyads; youth Mage = 13.96 years, range = 7.34–19.04). Unlike previous studies, parent and youth dyads reported on aggression they overtly perpetrated towards each other, meaning that discrepancies could not be attributed to informants being (un)able to observe those they are reporting on in different domains (e.g., parents being unable to observe youth aggression at school as well as at home).

Both parents and youth reported on parent-to-youth and youth-to-parent physical and psychological aggression via the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-2), and youth reported on their attachment anxiety and avoidance with their parent via the Adolescent Attachment Anxiety and Avoidance Inventory (AAAAI). We assessed informant discrepancies using two analytic techniques: polynomial regressions, which tested the absolute magnitude of association between youth and parents, as well as difference scores, which tested the direction of youth reports of the frequency of aggression relative to parent reports (i.e., did youth under- or over-report by comparison).

Using polynomial regressions, we found that dyads’ reports of youth-to-parent aggression showed more agreement at high versus low levels of attachment anxiety. Using difference scores, we also found that youth attachment anxiety was associated with youth over-reporting (relative to parents) on youth-to-parent and parent-to-youth aggression, whereas attachment avoidance was associated with youth over-reporting (relative to parents) on parent-to-youth aggression. The findings point to the importance of understanding attachment as a source of informant discrepancies between in social-emotional development and family functioning.

Data Availability

The data and materials that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the last author.

References

Bretherton I (1992) The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Dev Psychol 28(5):759–775. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.28.5.759

Mikulincer M (1995) Attachment style and the mental representation of the self. J Pers Soc Psychol 69(6):1203–1215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.6.1203

Mikulincer M, Florian V (1998) The relationship between adult attachment styles and emotional and cognitive reactions to stressful events. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS (eds) Attachment theory and close relationships. Guilford Press, New York, pp 143–165

Mikulincer M, Orbach I (1995) Attachment styles and repressive defensiveness: the accessibility and architecture of affective memories. J Pers Soc Psychol 68(5):917–925. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.5.917

Pietromonaco PR, Barrett LF (1997) Working models of attachment and daily social interactions. J Pers Soc Psychol 73(6):1409–1423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.6.1409

Feeney BC, Cassidy J (2003) Reconstructive memory related to adolescent-parent conflict interactions: the influence of attachment-related representations on immediate perceptions and changes in perceptions over time. J Pers Soc Psychol 85(5):945–955. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.945

Tolmacz R, Bachner-Melman R, Lev-Ari L, Almagor K (2022) Interparental conflict and relational attitudes within romantic relationships: the mediating role of attachment orientations. J Soc Pers Relat 39(6):1648–1668. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075211061617

Fearon RP, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH, Lapsley AM, Roisman GI (2010) The significance of insecure attachment and disorganization in the development of children’s externalizing behavior: a meta-analytic study. Child Dev 81(2):435–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01405.x

Collins NL, Feeney BC (2004) Working models of attachment shape perceptions of social support: evidence from experimental and observational studies. J Pers Soc Psychol 87(3):363–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.363

Mikulincer M, Shaver PR (2022) Enhancing the “broaden-and-build” cycle of attachment security as a means of overcoming prejudice, discrimination, and racism. Attach Hum Dev 24(3):260–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2021.1976921

Kurtz SM, Silverman JD (1996) The Calgary-Cambridge Referenced Observation Guides: an aid to defining the curriculum and organizing the teaching in communication training programmes. Med Educ 30(2):83–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.1996.tb00724.x

Leibowitz J, Ramos-Marcuse F, Arsenio WF (2002) Parent-child emotion communication, attachment, and affective narratives. Attach Hum Dev 4(1):55–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730210123157

Berger LE, Jodl KM, Allen JP, Davidson BM (2005) When adolescents disagree with others about their symptoms: differences in attachment organization as an explanation of discrepancies between adolescent-, parent-, and peer-reports of behavior problems. Dev Psychopathol 17:509–528. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579405050248

Borelli JL, Palmer A, Vanwoerden S, Sharp C (2019) Convergence in reports of adolescents’ psychopathology: a focus on disorganized attachment and reflective functioning. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 48:568–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2017.1399400

Ehrlich KB, Cassidy J, Dykas MJ (2011) Reporter discrepancies among parents, adolescents, and peers: adolescent attachment and informant depressive symptoms as explanatory factors. Child Dev 82(3):999–1012. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01530.x

Campbell L, Simpson JA, Boldry J, Kashy DA (2005) Perceptions of conflict and support in romantic relationships: the role of attachment anxiety. J Pers Soc Psychol 88(3):510–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.510

Overall NC, Fletcher GJ, Simpson JA, Fillo J (2015) Attachment insecurity, biased perceptions of romantic partners’ negative emotions, and hostile relationship behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol 108(5):730–749. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038987

Ehrlich KB, vanDellen MR, Felton JW, Lejuez CW, Cassidy J (2019) Perceptions about marital conflict: individual, dyadic, and family level effects. J Soc Pers Relat 36(11–12):3537–3553. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519829846

Laird RD, LaFleur LK (2016) Disclosure and monitoring as predictors of mother–adolescent agreement in reports of early adolescent rule-breaking behavior. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 45(2):188–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2014.963856

Edwards JR (1994) Regression analysis as an alternative to difference scores. J Manag 20(3):683–689. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639402000311

Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB (1996) The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2) development and preliminary psychometric data. J Fam Issues 17(3):283–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251396017003001

Lucente SW, Fals-Stewart W, Richards HJ, Goscha J (2001) Factor structure and reliability of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales for incarcerated female substance abusers. J Fam Violence 16(4):437–450. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012281027999

Newton RR, Connelly CD, Landsverk JA (2001) An examination of measurement characteristics and factorial validity of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale. Educ Psychol Meas 61(2):317–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164401612011

Vega EM, O’Leary KD (2007) Test–retest reliability of the revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2). J Fam Violence 22(8):703–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-007-9118-7

Hayre RS, Goulter N, Moretti MM (2019) Maltreatment, attachment, and substance use in adolescence: direct and indirect pathways. Addict Behav 90:196–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.10.049

Moretti MM, Bartolo T, Craig S, Slaney K, Odgers C (2014) Gender and the transmission of risk: a prospective study of adolescent girls exposed to maternal versus paternal interparental violence. J Res Adolesc 24(1):80–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12065

Moretti MM, Obsuth I (2009) Effectiveness of an attachment-focused manualized intervention for parents of teens at risk for aggressive behaviour: the Connect Program. J Adolesc 32(6):1347–1357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.07.013

Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR (1998) Self-report measurement of adult attachment: an integrative overview. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS (eds) Attachment theory and close relationships. Guilford Press, New York, pp 46–76

McKay S, Steiger AR (2003) Perceptions of parenting and attachment avoidance and anxiety: further validation of the Comprehensive Adolescent-Parent Attachment Inventory. Poster presented at the Biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development (SRCD), Tampa, Florida.

Moretti MM, Obsuth I, Craig SG, Bartolo T (2015) An attachment-based intervention for parents of adolescents at risk: mechanisms of change. Attach Hum Dev 17(2):119–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2015.1006383

Steiger AR (2003) Preliminary validation of the Comprehensive Adolescent–Parent Attachment Inventory. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, Canada

Steiger A, Moretti MM, Obsuth I (2009) An examination of complex interactions between parenting and attachment in the prediction of adolescent externalizing behavior. Poster presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Denver, USA

Craig SG, Sierra Hernandez C, Moretti MM, Pepler DJ (2021) The mediational effect of affect dysregulation on the association between attachment to parents and oppositional defiant disorder symptoms in adolescents. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 52:818–828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-01059-5

Dys SP, Balanji S, Thornton EM, McIntyre CL, Kristen A, Craig SG, Moretti MM (2023) Psychometric evaluation of the Adolescent Attachment Anxiety and Avoidance Inventory Short Form. Manuscript in preparation

Konishi C, Hymel S (2014) An attachment perspective on anger among adolescents. Merrill-Palmer Q 60(1):53–79. https://doi.org/10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.60.1.0053

Wong TK, Konishi C, Cho SB (2020) Paternal and maternal attachment: a multifaceted perspective on adolescents’ friendship. J Child Fam Stud. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01552-z

Laird RD, De Los Reyes A (2013) Testing informant discrepancies as predictors of early adolescent psychopathology: why difference scores cannot tell you what you want to know and how polynomial regression may. J Abnorm Child Psychol 41:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9659-y

Johnson PO, Neyman J (1936) Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Stat Res Mem 1:57–93

Cohen JE (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc, Hillsdale, New Jersey

De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE (2004) Measuring informant discrepancies in clinical child research. Psychol Assess 16(3):330–334. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.16.3.330

McCabe C, Kim D, King K (2018) Improving present practices in the visual display of interactions. Adv Methods Pract Psychol Sci 1(2):147–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245917746792

De Los Reyes A, Epkins CC, Asmundson GJG, Augenstein TM, Becker KD, Becker SP et al (2023) Editorial statement about JCCAP’s 2023 special issue on informant discrepancies in youth mental health assessments: observations, guidelines, and future directions grounded in 60 years of research. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 52(1):147–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2022.2158843

De Los Reyes A, Epkins CC (2023) Introduction to the special issue. A dozen years of demonstrating that informant discrepancies are more than measurement error: toward guidelines for integrating data from multi-informant assessments of youth mental health. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 52(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2022.2158843

Ehrlich KB, Richards J, Lejuez CW, Cassidy J (2016) When parents and adolescents disagree about disagreeing: observed parent-adolescent communication predicts informant discrepancies. J Res Adolesc 26:380–389. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12197

Karavasilis L, Doyle AB, Markiewicz D (2003) Associations between parenting style and attachment to mother in middle childhood and adolescence. Int J Behav Dev 27(2):153–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/0165025024400015

De Los Reyes A, Talbott E, Power T, Michel J, Cook CR, Racz SJ, Fitzpatrick O (2022) The Needs-to-Goals Gap: how informant discrepancies in youth mental health assessments impact service delivery. Clin Psychol Rev 92:102–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102114

Acknowledgements

We thank all the youth and parents who participated in our study.

Funding

This study was supported with a grant to M.M. by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR; Team Grant 251560) and the Canada Research Chairs program (CRC-2021-00302).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EMT drafted the manuscript, EMT, SPD, and CSH ran analyses. EMT and MMM conceptualized the study. SPD, CSH, RJS, and MMM, provided critical revisions to the manuscript. MMM supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Ethical Approval

All participants provided informed consent prior to participating in the study. This study received ethics approval from the Simon Fraser University Office of Research Ethics [protocol #2011s0284].

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thornton, E.M., Dys, S.P., Sierra Hernandez, C. et al. Parent–Youth Attachment Insecurity and Informant Discrepancies of Intrafamilial Aggression. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-023-01662-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-023-01662-2