Abstract

Human resilience to COVID-19 related stressors remains a pressing concern following the aftereffects of the pandemic and in the face of probable future pandemics. In response, we systematically scoped the available literature (n = 2030 records) to determine the nature and extent of research on emerging adults’ adaptive responses to COVID-19 stressors in the early stages of the pandemic. Using a multisystem resilience framework, our narrative review of 48 eligible studies unpacks the personal, relational, institutional and/or physical ecological resources that enabled positive emerging adult outcomes to COVID-18 stressors. We found that there is a geographical bias in studies on this topic, with majority world contexts poorly represented. Resources leading to positive outcomes foregrounded psychological and social support, while institutional and ecological supports were seldom mentioned. Multisystemic combinations of resources were rarely considered. This knowledge has valuable implications for understanding resilience in the context of other large-scale adverse conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Researcher attention to human resilience, or the capacity for positive outcomes (e.g., mental health) despite exposure to significant stress, continues to surge [1]. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which was announced by the World Health Organisation on 11 March, is implicit in this surge. Widespread pandemic-related threats to health and wellbeing animated calls to explain, and enable, human resilience to COVID-19 stressors [2]. While pandemic-related stressors prompted creative and innovative responses from some emerging adults (i.e., young people aged 18–29,[3], many faced significant risks to their physical and mental health [4]. Consequently, emerging adult resilience to pandemic-related stressors was labelled a particularly pressing agenda [5]. This scoping review interrogates researcher response to the latter.

The developmental phase of emerging adulthood is associated with specific tasks, including further education or training, career establishment, commitment to a long-term partner, and functional independence [3]. Failure to complete emerging adult developmental tasks results in immediate psychological distress and potentiates long-term negative impacts [6]. Accordingly, it is important to understand, and promote, emerging adult resilience to risks to developmental task fulfilment [7], including their resilience to COVID-19 stressors [5]. Nevertheless, previous reviews and meta-analyses have been inattentive to emerging adult resilience to COVID-19 stressors. They have instead foregrounded COVID-19 risks for emerging adult development, with emphasis on mental illness outcomes [8,9,10,11,12,13] and vaccination hesitancy [14].

In contrast to these risk-focused reviews, the current review considers the scope (i.e., extent, nature) of studies that investigated emerging adult resilience to COVID-19 stressors. In particular, it seeks to understand how emerging adult resilience was typically explained (i.e., which protective factors were associated with emerging adults’ positive outcomes). This intention is informed by a multisystemic resilience framework – i.e., the understanding that a composite of personal (biological or psychological), relational, institutional, and/or physical ecological (built and natural environment) resources enables positive outcomes in the face of significant stress [1, 15]. For instance, a pre-COVID study of emerging adult resilience to the challenges of structural violence in a South African context reported a combination of protective resources that included personal strengths (i.e., physical health; future-oriented agency), relational resources (i.e., caring family; supportive peers; enabling community), and built environment resources (i.e., an accessible recreation centre) [17].

Although the worst of the COVID pandemic appears to be over globally, the multisystemic sources of emerging adult resilience to COVID-19-related adverse conditions are incompletely understood. They need further investigation and documentation to contribute to the global knowledge base, not least because future pandemics are forecast [18]. While this information will be important for the wellbeing of all young people, its value is heightened for those living in majority world contexts [19]. Following Punch and Tisdall [20], we prefer ‘majority world’ and ‘minority world’ to the more conventional references to ‘the third world’/’Global South’ and ‘the first world’/’Global North’. The term ‘majority world’ signals that “the ‘majority’ of population, poverty, land mass and lifestyles is located in the former, in Africa, Asia and Latin America” [20], p. 241). In using this term, we nudge attention to the resilience of most of the world’s youth (i.e., vast numbers of young people who are typically over-exposed to chronic stress and under-represented in the literature).

Despite growing research on resources that supported young adults during COVID-19 times, no evidence synthesis has been done on these studies. A preliminary search in MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and the JBI Evidence Synthesis found no scoping or other systematic reviews with a multisystemic resilience focus on the topic. While there are multiple forms of evidence syntheses, we chose to conduct a scoping review. Scoping reviews aim to synthesise the literature to provide a broad overview of a specific topic, provide insight into how that topic has been researched, and inform future scientific inquiry [21]. Our review question, and inclusion/exclusion criteria were developed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) PCC (Participant; Concept; Context) framework [21]. The following broad question informed our scoping review: what resources supported the resilience of emerging adults (as evidenced in positive outcomes) during the early stages (i.e., January 2020 to June 2021) of the COVID-19 pandemic? Following vaccination rollout to the public (typically toward the end of 2020 in minority world contexts like North America and Europe and around mid-2021 in majority world countries; [22, 23], COVID-related distress was less pronounced than in earlier pandemic stages [24]. Earlier stages were generally characterised by lockdown-related disruptions to daily routine, education, livelihoods, and relationships, as well as significant contagion/mortality fears. Understanding what supported resilience to these stressors will advance pro-active preparation for future pandemics [18], with emphasis on championing resilience from the earliest stages of future pandemics.

Method

To conduct the scoping review, we followed the steps originally advised by Arksey and O'Malley [25] and then others [21, 26, 27]. Reporting of the findings aligns with the PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [27].

Eligibility Criteria

To be included, papers needed to report (i) an empirical study (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods) that (ii) investigated any positive outcome among emerging adults (i.e., 18–29-year-olds; [3] exposed to COVID-19 related stress and (iii) the protective factor/s associated with those positive outcomes. In line with the resilience literature [28], a positive outcome in the face of COVID-related stressors could include physical health, mental health (e.g., limited/no symptoms of depression), subjective wellbeing, quality of life, engagement in education, and/or academic progress/achievement. However, we excluded studies that reported interventions to support these outcomes or that recommended/theorised how to achieve positive outcomes during COVID-challenged times. We excluded studies that implied that participants could be emerging adults (e.g., references to students), but that provided no proof (i.e., average age or age range consistent with emerging adulthood). We also excluded studies that had a range of participants (e.g., adolescents to elderly persons), but reported no findings that were specific to emerging adults.

Information Sources and Search

A trained research assistant (i.e., a research psychology Master’s student) searched for relevant academic journal publications using multiple databases: Africa-Wide, CINAHL, ERIC, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO (all via EBSCOhost platform); Medline (via Web of Science Clarivate Analytics); PubMed; Scopus (which includes contents of Embase); Web of Science Core Collection; and SciELO Citation Index. Given concerns about the quality of many COVID-19-related studies [29], we delimited eligibility to full-text journal papers. The search was conducted in September 2021 to retrieve eligible studies published between January 2020 and August 2021.

Because of extensive prior experience in conducting resilience-focused reviews [16, 30,31,32,33,34,35], we did not invite a librarian to draft the search strategy. We repeated the search terms from those reviews and added COVID-19. The search terms were: Resilien* or strengths or coping or hardiness or adaptation or grit or perseverance or protective factors or promotive factors or buffer* or positive adjustment or positive effects or benefits AND emerging adult or college student or young adult or early career or young people or youth AND COVID-19 or Coronavirus or 2019-ncov or sars-cov-2 or cov-19 or covid pandemic. The search terms were applied to titles, abstracts, and keywords/subject terms.

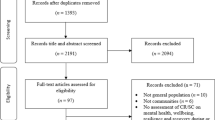

In total, the search yielded 2030 records (see Fig. 1). We exported a detailed view of each record into Endnote. We used this software to identify duplicates and ineligible records (n = 1331; see Fig. 1). Before deleting the duplicates, we verified that the record was in fact a duplicate. The removal of these records resulted in 699 records for screening.

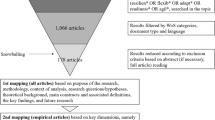

Two authors (AF; LT) screened the records. Using the blind procedure function in Rayyan software, they independently perused the titles and abstracts of all records to confirm record consistency with specified eligibility criteria (i.e., empirical study documenting positive emerging adult outcomes during COVID-19-challenged times and the protective factors associated with those outcomes). Following Saldana [36], they held consensus discussions to resolve the isolated discrepancies (n = 29; 4.1% of the records). The screening resulted in 117 records that were considered for selection. After a decision was made on the included studies, the reference lists of the included studies were screened to identify further eligible studies. No further eligible studies were found.

Selection of Sources of Evidence

A post-doctoral fellow (TA) and qualified research psychologist (GR) independently read the full texts to confirm their fit with the specified eligibility criteria. Following a consensus discussion to resolve the discrepancies in their assessments (n = 8; 6.8% of the records), they recommended exclusion of 69 full texts (see Fig. 1). Two authors (AN; KC) confirmed their recommendations.

Data Charting Process

To chart the data, AF and LT designed a data charting form. It included the study’s purpose; date/s when study conducted; geographical context; design; sample (size and specifics); positive outcomes and how they were measured/investigated; and factors that were associated with positive outcomes. Once they had piloted the chart with 10 full texts, they shared it with TA and GR who independently extracted data from the remaining full texts. AF, AN, KC, and LT confirmed and, where necessary, refined that data extraction.

Collating, Summarising and Reporting the Results

Guided by Petticrew and Roberts [37], and JBI's recent publication on qualitative content analysis in scoping reviews [38], we conducted a narrative synthesis. We tabulated essential aspects of the included studies, including their design, location, and positive outcome/s reported. We were particularly attentive to the protective factors associated with these outcomes. In line with the multisystemic resilience framework [1, 15], we considered the nature of these protective factors and how often that nature reflected a combination of factors (e.g., psychological strengths and social supports) versus single system factors (e.g., only psychological strengths).

Results

Our search generated 2030 records, of which 699 were screened after removal of duplicates and records marked as ineligible by automation tools. Of these, 117 full text articles were retrieved and assessed for eligibility, and 48 were subsequently included in the review (see Fig. 1). We summarise key details of the included studies in Table 1. In what follows, we provide an overview of these studies (i.e., where conducted, design detail, and positive outcomes of interest), before detailing patterns in the protective factors associated with the positive outcomes that the studies reported.

Overview of the Included Studies

Nineteen countries were represented in the included studies (i.e., Australia; Belgium; Canada; China; Ethiopia; Greece; India; Israel; Italy; Japan; Pakistan; Peru; the Philippines; Saudi Arabia; South Africa; Switzerland; the UK; the USA; Vietnam). Most studies were conducted in Asia and the Pacific (n = 23), with China being most prominent within that region (n = 15). Europe (n = 10), with emphasis on Italy (n = 7), was fairly well represented, as was North America (n = 8). Three studies were conducted in the Middle East, three in sub-Saharan Africa, and one in South America.

Most included studies employed a cross-sectional survey design (n = 36; see Table 1). These studies typically sampled college/university students in which young women represented the majority; sample sizes ranged from N = 131 [39] to N = 24,678 [40]. Longitudinal studies were scarce (n = 5), and in all instances relied on cohorts that were established prior to the COVID-19 pandemic [41,42,43,44,45]. Qualitative studies were also rare (n = 4), and except for Xu et al. [47], conducted in majority world countries (i.e., South Africa, [48], India, [49, 50]. Only one of the included studies, i.e., Son et al.’s [51] study with undergraduates in the USA, reported a mixed methods design.

In most included studies, the positive outcome of interest related to mental health (typically lower levels of psychological distress, including anxiety and depression). A handful of included studies (n = 6) focused on constructive management/avoidance of loneliness and/or lockdown fatigue. Only five of the included studies reported positive psychology outcomes (i.e., flourishing, quality of life; post-traumatic growth/positive change; life satisfaction). A single study reported knowing how best to avoid/limit COVID-19 contagion as a positive outcome [48].

Patterns in the Protective Factors Associated with Emerging Adult Resilience to COVID-19 Stress

As summarised in Table 1, the included studies reported a variety of protective factors associated with positive outcomes in the face of COVID-19-related challenges, including personal resources (e.g., constructive coping skills or an altruistic disposition), relational resources (e.g., supportive family or friends), and less often, institutional or ecological resources (e.g., employment; access to sports facilities or green spaces). Closer inspection of these protective factors showed two prominent patterns: inattention to multisystemic resilience resource combinations (i.e., personal resources dominated accounts of emerging adult resilience to COVID-19 stressors) and, when resource combinations were reported, psychological resources and social supports were preponderant. These patterns are detailed next.

Inattention to Multisystemic Resource Combinations

Most included studies (n = 29) did not report a combination of resources that were distributed across multiple systems (e.g., the self, family, and built environment). Instead, and as explained below, they typically reported only personal resources (n = 23). A few (n = 5) reported only relational resources (i.e., family, peers, and/or supportive professors) and associated social support, [43, 47, 52,53,54]. A single study reported neighbourhood factors only (i.e., childhood exposure to neighbourhood disadvantage) and theorised how this exposure facilitated psychological steeling that scaffolded positive responses to COVID-related challenges [41].

In the studies reporting personal strengths only, adaptive coping skills (e.g., hopeful meaning making, listening to music, judicious media use, or maintaining a daily routine) were prominently associated with positive outcomes (n = 9; [39, 44, 55,56,57,58,59,60,61]). Personal or psychological resilience was reported almost as regularly as coping skills (n = 8), but variably operationalised. Operationalisations included psychological capital [56], ego resilience [62], capacity to ‘bounce back’ [59, 63], and/or assets/resources at the level of the individual [46, 60, 64, 65].

Less commonly reported personal protective factors included being well informed about/enacting COVID-19 mitigation measures [40, 45, 66]. Similarly, only two studies associated young people’s altruistic or collectivist orientation with positive outcomes; both were conducted with young people from European countries that value family and community and encourage collectivist values [58, 68]. There was isolated consideration of the protective value of traditional and/or positive psychology constructs, including self-concept clarity [69]; sense of coherence Li, Xu, He et al., [70]; meaning in life [71], life satisfaction [62], mindfulness and flow [72], and internal locus of control [73].

Resource Combinations Foreground Psychological Resources and Social Supports

Nineteen studies associated multiple resources with emerging adult positive outcomes in the face of COVID-related stressors. Most (n = 13) reported a combination that drew on personal and relational factors [42, 49, 51, 67, 74,75,76,77,78, 80, 81, 83]. While these studies seldom specified details of the relational resources (e.g., they referred broadly to social support), four did specify family [42, 51, 78, 83], one referred to friends [51], and one included mental health practitioners [78]. Only two studies (i.e., [67, 81] specified that young people needed to experience the relationships in question as secure/having medium to high quality for them to be protective.

Resource combinations seldom reported institutional supports. Exceptions included reference to effective public health campaigns [48], opportunity for employment and/or education [84, 85], and media-facilitated information that was trustworthy [79]. Similarly, combinations rarely included resources in the physical ecology. The only study to explicitly report physical ecological resources was Oswald et al. [85]. In addition to secure employment, social interaction and hopefulness, this Australian study associated unintentional or intentional contact with nature (e.g., outdoor garden) with young people’s capacity to flourish. Two other studies implied physical ecological resources in the resource combinations they reported. While detailing ways that Indian young adults coped adaptively with COVID-related stressors, Suhail et al. [50] reported a participant’s account of taking their dog for a walk and of appreciating nature. Similarly, Golemis et al. [86] included sporting and religious activity in the resource combination that protected Greek participants thereby suggesting access to outdoor/indoor spaces that facilitated sporting activity.

Discussion

Our aim with this paper was to scope the literature to determine the nature and extent of researcher response to calls to account for human resilience—especially emerging adult resilience—to COVID-19 stressors [2, 5]. In particular, we were interested in understanding how emerging adult resilience was typically accounted for during the early stages of the pandemic (i.e., patterns in the protective factors associated with emerging adults’ positive outcomes). We believe that these insights are pivotal to emerging adult resilience to subsequent pandemics, but also to how researchers conceptualise future emerging adult resilience studies.

Our review points to a geographical bias in studies of emerging adult resilience to COVID-19 stress. While it is heartening that researcher response to calls to investigate emerging adult resilience included young people from multiple countries across multiple regions, studies in Asia and the Pacific (especially China) were predominant, followed by North America (especially the USA) and Europe (especially Italy). This apparent bias could relate to the pandemic originating in Asia (specifically China) and/or European countries (including Italy) and the USA reporting of the highest COVID-19 infection rates globally [87]. However, it is also possible that it is a sign of researchers being under-attentive to emerging adults in majority world contexts like Africa and South America. Certainly, this trend was reported in pre-COVID-19 reviews of young people’s mental health (e.g., [16, 88]. Given the relentless challenges that demand resilient responses from young people in majority world contexts like South America and Africa [89], and the concerns that future pandemics will (again) have disproportionately negative impacts on disadvantaged majority world youth [19], it is important that studies of their resilience be fast-tracked.

Our review also identified a sampling bias in studies of emerging adult resilience to COVID-19 stress, in that college/university students dominated the samples. While college and university closures and the introduction of virtual classes meant that students were particularly vulnerable to stress during the early stages of the pandemic [90], the over-representation of students in the studies we reviewed raises questions about the applicability of the findings to emerging adults not involved in employment, education, or training (NEET). Pre-Covid, NEETs were already a growing population in need of intervention [91]. COVID-related disruptions to livelihoods and economies make understanding of resilience among NEET emerging adults even more pressing.

Of most concern, however, is that our review shows that studies of emerging adult adaptation to early pandemic stressors were inclined to perpetuate outdated understandings of resilience as a solo endeavour. More studies reported personal strengths than studies reporting resource combinations. While personal strengths are important resilience-enablers, they cannot fully account for why stress-exposed young people show positive outcomes [28]. Instead, as multisystemic resilience frameworks show, positive outcomes are co-enabled by a combination of resources that go beyond personal strengths [1, 15], also among emerging adults [17, 92].

While it was reassuring to see that 19 studies did not restrict what enabled positive outcomes to personal strengths, most (n = 13) of these studies reported an attenuated combination (i.e., personal and relational resources). If emerging adult resilience is to be optimized, particularly during pandemic-challenged times, then more studies like that of Oswald et al. [85] are urgently needed. Their study was distinguished by its explicit investigation of multiple resources and multiple system levels, including the physical ecology. Future studies of emerging adult resilience need to be purposefully multisystemic. Put differently, they need to be designed to investigate the biological, psychological, relational/social, institutional, and physical ecology resources that matter for emerging adult resilience and to consider how identified resource combinations are responsive to situational and cultural context [15]. Moreover, they need to consider what the optimal number of resources in such a resource combination might be [93]. The latter is particularly important in pandemic-challenged times that are associated with austerity and resource constraints.

Limitations

Early adaptive responses, like those documented in this review, might differ from those in later stages of the pandemic, especially once vaccines were freely available [94]. A follow-up review would address this limitation. In addition, the focus on student samples limits the generalizability of findings beyond this group. The exclusion of grey literature from the review means that some unpublished studies that present different findings are not reflected here.

Conclusion

The decline in pandemic related stressors should not breed complacency. Future pandemics are likely [18]. A takeaway from our review of what enabled the resilience of emerging adults during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic is that preparation aimed at advancing resilience to future pandemics must shift its focus from individual resources to resource combinations rooted in multiple systems. In doing so, optimal preparation will require special attention to the capacity of education, health, economic and built/natural ecology systems to support emerging adult resilience. Continued inattention to these broader systems will force emerging adults and their families/friends to continue to take primary responsibility for positive adjustment to future stressors and support the longevity of neoliberal agendas.

Summary

This scoping review provides a detailed overview of the nature and extent of empirical research on emerging adults’ adaptive responses to COVID-19 stressors in the early stages of the pandemic. Following PRISMA guidelines, we included 48 studies of emerging adult resilience to COVID-19 stressors. Using a multisystem resilience framework and narrative review approach, we found that most studies reported person-focused or individualised accounts of young people’s resilience (despite such narrow accounts being disparaged by recent developments in resilience science). Multisystemic combinations of resources were rarely considered (despite new developments in resilience science pointing to the salience of a mix of multisystemic resources to youth resilience). When studies did report a combination of resources, they foregrounded psychological and social supports and seldom mentioned institutional and ecological supports. There was also a geographical bias in the included studies, with the majority world contexts of Africa and Latin America poorly represented. This synthesis advances a multisystemic research agenda informed by resilience studies that are purposefully designed to measure biological, psychological, social, institutional, and environmental resources in order to more fully account for young people’s capacity to respond adaptively to significant stress. Also, these studies should purposefully end the historic researcher neglect of young people in majority world contexts, with special attention to young people in Africa and Latin America.

Data Availability

Included publications are marked with * in the reference list; the extracted data are included in Table 1.

References

Masten AS, Lucke CM, Nelson KM, Stallworthy IC (2021) Resilience in development and psychopathology: multisystem perspectives. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 17(1):521–549. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-081219-120307

Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH et al (2020) Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 7:547–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

Arnett JJ (2000) Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol 55(5):469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

Mudiriza G, De Lannoy A (2020) Youth emotional well-being during the COVID-19-related lockdown in South Africa. SALDRU, UCT, Cape Town. (SALDRU Working Paper No. 268). https://www.opensaldru.uct.ac.za/bitstream/handle/11090/991/2020_268_Saldruwp.pdf?sequence=1

OECD. (2020, June 11). Youth and COVID-19: Response, recovery and resilience. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/youth-and-covid-19-response-recovery-and-resilience-c40e61c6/

Arnett JJ, Žukauskienė R, Sugimura K (2014) The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: implications for mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry 1(7):569–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00080-7

Burt KB, Paysnick AA (2012) Resilience in the transition to adulthood. Dev Psychopathol 24(2):493–505. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579412000119

Wang C, Wen W, Zhang H, Ni J, Jiang J, Cheng Y, Zhou M, Ye L, Feng Z, Ge Z, Luo H, Wang M, Zhang X, Liu W (2021) Anxiety, depression, and stress prevalence among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2021.1960849

Buizza C, Bazzoli L, Ghilardi A (2022) Changes in college students mental health and lifestyle during the covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Adolesc Res Rev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-022-00192-7

Chang J-J, Ji Y, Li Y-H, Pan H-F, Su P-Y (2021) Prevalence of anxiety symptom and depressive symptom among college students during COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 292:242–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.109

Elharake JA, Akbar F, Malik AA, Gilliam W, Omer SB (2022) Mental health impact of COVID-19 among children and college students: a systematic review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-021-01297-1

Lee Y, Jeon YJ, Kang S, Shin JI, Jung Y-C, Jung SJ (2022) Social media use and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in young adults: a meta-analysis of 14 cross-sectional studies. BMC Public Health 22(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13409-0

Mao J, Gao X, Yan P, Ren X, Guan Y, Yan Y (2021) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health and learning of college and university students: a protocol of systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 11(7):e046428. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046428

Geng H, Cao K, Zhang J, Wu K, Wang G, Liu C (2022) Attitudes of COVID-19 vaccination among college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis of willingness, associated determinants, and reasons for hesitancy. Hum Vaccin Immunother 18(5):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2054260

Ungar M, Theron L (2020) Resilience and mental health: how multisystemic processes contribute to positive outcomes. Lancet Psychiatry 7(5):441–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30434-1

Theron LC, Abreu-Villaça Y, Augusto-Oliveira M, Brennan CH, Crespo-Lopez ME, de Paula Arrifano G, Glazer L, Gwata N, Lin L, Mareschal S, Sartori L, Stieger L, Trotta A, Hadfield K (2022) A systematic review of the mental health risks and resilience among pollution-exposed adolescents. J Psychiatr Res 146:55–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.12.012

Theron LC, Murphy K, Ungar M (2022) Multisystemic resilience: learning from youth in stressed environments. Youth Soc 54(6):1000–1022. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X211017335

Michie S, West R (2021) Sustained behavior change is key to preventing and tackling future pandemics. Nat Med 27(5):749–752. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01345-2

Kyeremateng R, Oguda L, Asemota O (2022) COVID-19 pandemic: health inequities in children and youth. Arch Dis Child 107(3):297–299. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2020-320170

Punch S, Tisdall EKM (2012) Exploring children and young people’s relationships across Majority and Minority Worlds. Child Geogr 10(3):241–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2012.693375

Peters MD, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, McInerney P, Godfrey CM, Khalil H (2020) Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth 18(10):2119–2126. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbies-20-00167

Ekwebelem OC, Yunusa I, Onyeaka H, Ekwebelem NC, Nnorom-Dike O (2021) COVID-19 vaccine rollout: will it affect the rates of vaccine hesitancy in Africa? Public Health 197:e18–e19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2021.01.010

Zaqout A, Daghfal J, Alaqad I, Hussein SA, Aldushain A, Almaslamani MA, Abukhattab AS, Omrani AS (2021) The initial impact of a national BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine rollout. Int J Infect Dis 108:116–118. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.26.21256087

Yang X, Xiong Z, Li Z, Li X, Xiang W, Yuan Y, Li Z (2020) Perceived psychological stress and associated factors in the early stages of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic: evidence from the general Chinese population. PLoS One 15(12):e0243605. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243605

Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 8(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O'Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, Moher D (2014) Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol 67(12), 1291–1294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W et al (2018) PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 169(7):467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-0850

Masten AS (2014) Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. Guilford Publications, New York City

Khatter A, Naughton M, Dambha-Miller H, Redmond P (2021) Is rapid scientific publication also high quality? Bibliometric analysis of highly disseminated COVID-19 research papers. Learn Pub 34(4):568–577. https://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1403

Fouché A, Fouche DF, Theron LC (2020) Child protection and resilience in the face of COVID-19 in South Africa: a rapid review of C-19 legislation. Child Abuse Neglect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104710

Haffejee S, Theron L (2017) Resilience processes in sexually abused adolescent girls: a scoping review of the literature. South Afr J Sci 113(9/10):9. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2017/20160318

Jefferis TC, Theron LC (2018) Explanations of resilience in women and girls: how applicable to black South African girls. Women’s Studies Int Forum 69:195–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2018.03.006

Theron LC (2020) Resilience of sub-Saharan children and adolescents: a scoping review. Transcult Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461520938916

Theron LC, Theron AMC (2010) A critical review of studies of South African youth resilience, 1990–2008: review article. S Afr J Sci. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajs.v106i7/8.252

Van Breda AD, Theron LC (2018) A critical review of South African child and youth resilience studies, 2009–2017. Child Youth Serv Rev 91:237–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.06.022

Saldana J (2009) The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage

Petticrew M, Roberts H (2008) Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken

Pollock D, Peters MD, Khalil H, McInerney P, Alexander L, Tricco AC, Evans C, de Moraes EB, Godfrey CM, Pieper D, Saran A, Munn Z (2022) Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth 21(3):520–532. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbies-22-00123

*Mushquash AR, Grassia E (2021) Coping during COVID-19: Examining student stress and depressive symptoms. J Am Coll Health 70(8):2266–2269. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1865379

*Guan J, Wu C, Wei D, Xu Q, Wang J, Lin H, Wang C, Mao Z (2021) Prevalence and factors for anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic among college students in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(4974):1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094974

*Bleil EM, Appelhans BM, Thomas AS, Gregorich SE, Marquez N, Roisman GI, Booth-LaForce C, Crowder K (2021) Early life predictors of positive change during the coronavirus disease pandemic. BMC Psychol 9(83):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00586-7

*Hyun S, Wong GTF, Levy-Carrick NC, Charmaran L, Cozier Y, Yip T, Hahm C, Liu CH (2021) Psychosocial correlates of posttraumatic growth among US young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res 302:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114035

*Porter C, Favara M, Hittmeyer A, Scott D, Jiménez AS, Ellanki R, Woldehanna T, Duc LT, Craske MG, Stein A (2021) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety and depression symptoms of young people in the global south: evidence from a four-country cohort study. BMJ Open 11(e049653):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049653

*Shanahan L, Steinhoff A, Bechtiger L, Murray AL, Nivette A, Hepp U, Ribeaud D, Eisner M (2020) Emotional distress in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence of risk and resilience from a longitudinal cohort study. Psychol Med. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172000241X

*Zhang K, Lin Z, Peng Y, Li L (2021) A longitudinal study on psychological burden of medical students during COVID-19 outbreak and remission period in China. Eur J Psychiatry 35(2021):234–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpsy.2021.06.003

*Zhang L, Wang L, Liu Y, Zhang J, Zhang X, Zhao J (2021) Resilience predicts the trajectories of college students’ daily emotions during COVID-19: a latent growth mixture model. Front Psychol 12(648368):1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648368

*Xu Y, Gibson D, Pandey T, Jiang Y, Olsoe B (2021) The lived experiences of Chinese international college students and scholars during the initial COVID-19 quarantine period in the United States. Int J Adv Couns 43:534–552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-021-09446-w

*Gittings L, Toska E, Medley S, Cluver L, Logie CH, Ralayo N, Chen J, Mbithi-Dikgole J (2021) ‘Now my life is stuck!’: Experiences of adolescents and young people during COVID-19 lockdown in South Africa. Glob Public Health 16(6):947–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1899262

*Raj T, Bajaj A (2021) Living alone in lockdown: impact on mental health and coping mechanisms among young working adults. Curr Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01511-2

*Suhail A, Iqbal N, Smith J (2021) Lived experiences of Indian Youth amid COVID-19 crisis: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Int J Soc Psychiatry 67(5):559–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020966021

*Son C, Hedge S, Smith A, Wang X, Sasangohar F (2020) Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: interview survey study. J Med Internet Res 22(9):e21279. https://doi.org/10.2196/21279

*Li X, Wu H, Meng F, Li L, Wang Y, Zhou M (2020) Relations of COVID-19-related stressors and social support with Chinese college students’ psychological response during the covid-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry 11:551315. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.551315

*Pompili S, Tata DD, Bianchiy D, Lonigro A, Zammuto M, Baiocco R, Longobardi E, Laghi F (2021) Food and alcohol disturbance among young adults during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy: risk and protective factors. Eating Weight Disord Stud Anorexia Bulimia Obesity 27:769–780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01220-6

*Woznicki N, Arriaga AS, Caporale-Berkowitz NA, Parent MC (2020) Parasocial relationships and depression among LGBQ emerging adults living with their parents during COVID-19: the potential for online support. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers 8(2):228–237

*Alsolais A, Alquwez N, Alotaibi KA, Alqarni AS, Almalki M, Alsolami F, Almazan J, Cruz JP (2021) Risk perceptions, fear, depression, anxiety, stress and coping among Saudi nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Ment Health 30(2):194–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.1922636

*Dongmei LI (2020) Influence of the youth’s psychological capital on social anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak: the mediating role of coping style. Iran J Public Health 49(11):2060–2068. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v49i11.4721

*Eden AL, Johnson BK, Reinecke L, Grady SM (2020) Media for coping during COVID-19 social distancing: stress, anxiety, and psychological well-being. Front Psychol 11:1–21. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577639

*Kornilaki EN (2021) The psychological effect of COVID-19 quarantine on Greek young adults: risk factors and the protective role of daily routine and altruism. Int J Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12767

*LaBrague LJ, Ballad CA (2020) Lockdown fatigue among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: predictive role of personal resilience, coping behaviors, and health. Perspect Psychiatr Care 57(4):1905–1912. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12765

*Savitsky B, Findling Y, Ereli A, Hendel T (2020) Anxiety and coping strategies among nursing students during the covid-19 pandemic. Nurse Educ Pract 46:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102809

*Vidas D, Larwood JL, Nelson NL, Dingle GA (2021) Music listening as a strategy for managing covid-19 stress in first-year university students. Front Psychol 12(647065):1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647065

*Padmanabhanunni A, Pretorious TB (2021) The loneliness–life satisfaction relationship: the parallel and serial mediating role of hopelessness, depression and ego-resilience among young adults in South Africa during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(7):1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073613

*Padmanabhanunni A, Pretorious TB (2021) The unbearable loneliness of COVID-19: COVID-19-related correlates of loneliness in South Africa in young adults. Psychiatry Res 296:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113658

*Tan Y, Huang C, Geng Y, Cheung SP, Zhang S (2021) Psychological well-being in Chinese college students during the covid-19 pandemic: roles of resilience and environmental stress. Front Psychol 12(671553):1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.671553

*Ye B, Zhou X, Im H, Liu M, Wang XQ, Yang Q (2020) Epidemic rumination and resilience on college students’ depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating role of fatigue. Front Public Health 8(560983):1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.560983

*Khalid A, Younas MW, Khan H, Khan MS, Malik AR, Butt AU, Ali B (2021) Relationship between knowledge on COVID-19 and psychological distress among students living in quarantine: an email survey. AIMS Public Health 8(1):90–99. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2021007

*Germani A, Buratta L, Delvecchia E, Gizzi G, Mazzeschi C (2020) Anxiety severity, perceived risk of covid-19 and individual functioning in emerging adults facing the pandemic. Front Psychol 11(567505):1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567505

*Germani A, Buratta L, Delvecchia E, Mazzeschi C (2020) Emerging adults and COVID-19: the role of individualism-collectivism on perceived risks and psychological maladjustment. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(10):3497. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103497

*Alessandri G, De Longis E, Golfieri F, Crocetti E (2021) Can self-concept clarity protect against a pandemic? A daily study on self-concept clarity and negative affect during the covid-19 outbreak. Identity 21(1):6–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2020.1846538

*Li M, Xu Z, He X, Zhang J, Song R, Duan W, Liu T, Yang H (2021) Sense of coherence and mental health in college students after returning to school during COVID-19: the moderating role of media exposure. Front Psychol 12:687928. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.687928

*Lin L (2020) Longitudinal associations of meaning in life and psychosocial adjustment to the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Br J Health Psychol 26(2):525–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12492

*Sweeny K, Rankin K, Cheng X, Hou L, Long F, Meng Y, Azer L, Zhou R, Zhang W (2020) Flow in the time of COVID-19: findings from China. PLoS One 15(11):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242043

*Xia Y, Fan Y, Liu T, Ma Z (2021) Problematic Internet use among residential college students during the COVID-19 lockdown: a social network analysis approach. Journal of Behavioural Addictions 10(2):253–262. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2021.00028

*Agbaria Q, Mokh AA (2021) Coping with stress during the coronavirus outbreak: the contribution of big five personality traits and social support. Int J Ment Heal Addict 20(3):1854–1872. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00486-2

Hou J, Yu Q, Lan X (2021) COVID-19 Infection risk and depressive symptoms among young adults during quarantine: the moderating role of grit and social support. Front Psychol 11:1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577942

*Jin L, Hao Z, Huang J, Akram HR, Saeed MF, Ma H (2021) Depression and anxiety symptoms are associated with problematic smartphone use under the COVID-19 epidemic: the mediation models. Child Youth Serv Rev 121:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105875

Lardone A, Sorrentino P, Giancamilli F, Palombi T, Simper T, Mandolesi L, Lucidi F, Chirico A, Galli F (2020) Psychosocial variables and quality of life during the COVID-19 lockdown: a correlational study on a convenience sample of young Italians. PeerJ 8:e10611. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10611

*Li Y, Peng J (2021) Does social support matter? The mediating links with coping strategy and anxiety among Chinese college students in a cross-sectional study of COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 21(1298):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11332-4

*Li M, Liu M, Yang Y, Wang Y, Xiaoshi Y, Wu H (2020) Psychological impact of health risk communication and social media on college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-Sectional Study. J Medical Internet Res 22(11):1–13. https://doi.org/10.2196/20656

*Marchini S, Zaurino E, Bouziotis J, Brondino N, Delvenne V, Delhaye M (2020) Study of resilience and loneliness in youth (18–25 years old) during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown measures. J Commun Psychol 49:468–480. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22473

*Nola M, Guiot C, Damiani S, Brondino N, Miliani R, Politi P (2021) Not a matter of quantity: quality of relationships and personal interests predict university students’ resilience to anxiety during CoViD-19. Curr Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02076-w

*Nomura K, Minamizono S, Maeda E, Kim R, Iwata T, Hirayama J, Ono K, Fushimi M, Goto T, Mishima K, Yamamoto F (2021) Cross-sectional survey of depressive symptoms and suicide-related ideation at a Japanese national university during the COVID-19 stay-home order. Environ Health Prev Med 26(30):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-021-00953-1

Liu CH, Zhang E, Wong GTF, Hyun S, Hahm HC (2020) Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical implications for U.S. young adult mental health. Psychiatry Res 290:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113172

*Hu Y, Morrison Gutman L (2021) The trajectory of loneliness in UK young adults during the summer to winter months of COVID-19. Psychiatric Res 303:114064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114064

*Oswald TK, Rumbold AR, Kedzior SGE, Kohler M, Moore VM (2021) Mental health of young Australians during the COVID-19 pandemic: exploring the roles of employment precarity, screen time, and contact with nature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpsy.2021.06.003

*Golemis A, Voitsidis P, Parlapani E, Nikopoulou VA, Tsipropoulou V, Karamouzi P, Giazkoulidou A, Dimitriadou A, Kafetzopoulou C, Holvena V, Diakogiannis I (2021) Young adults’ coping strategies against loneliness during the COVID-19-related quarantine in Greece. Health Promotion Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114064

Elflein, J. (2022, December 22). Rate of COVID-19 cases in the most impacted countries worldwide as of December 22, 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1174594/covid19-case-rate-select-countries-worldwide/

Rother H, Etzel RA, Shelton M, Paulson JA, Hayward RA, Theron LC (2021) Impact of extreme weather events on Sub-Saharan African child and adolescent mental health: the implications of a systematic review of sparse research findings. J Climate Change Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100087

Sankoh O, Sevalie S, Weston M (2018) Mental health in Africa. Lancet Glob Health 6(9):e954–e955. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30303-6

Alomyan H (2021) The impact of distance learning on the psychology and learning of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Instruct 14(4):585–606. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2021.14434a

Mawn L, Oliver EJ, Akhter N, Bambra CL, Torgerson C, Bridle C, Stain HJ (2017) Are we failing young people not in employment, education or training (NEETs)? A systematic review and meta-analysis of re-engagement interventions. Syst Rev 6:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0394-2

Theron LC, Levine D, Ungar M (2021) African emerging adult resilience: insights from a sample of township youth. Emerg Adulthood 9(4):360–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696820940077

Sherr L, Haag K, Tomlinson M, Rudgard WE, Skeen S, Meinck F, Du Toit SM, Roberts S, Gordon SL, Desmond C, Cluver L (2023) Understanding accelerators to improve SDG-related outcomes for adolescents–an investigation into the nature and quantum of additive effects of protective factors to guide policy making. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278020

Reile R, Kullamaa L, Hallik R, Innos K, Kukk M, Laidra K, Nurk E, Tamson M, Vorobjov S (2021) Perceived stress during the first wave of COVID-19 outbreak: results from nationwide cross-sectional study in Estonia. Front Public Health 9:564706. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.564706

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Pretoria. This review was funded by the National Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences, South Africa [grant number: JNI20/1009].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LT conceptualized the review, with input from KC and AF. All authors contributed to review process. LT led the write up with input from KC and AF. All other authors provided editorial input.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

Authors have none to declare.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable: this systematic review involved no human/animal participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Theron, L.C., Cockcroft, K., Annalakshmi, N. et al. Emerging Adult Resilience to the Early Stages of the COVID-Pandemic: A Systematic Scoping Review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-023-01585-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-023-01585-y