Abstract

The study aimed to examine the mechanism underlying the effect of basic psychological needs satisfaction (BPNs) on depression via feelings of safety or rumination in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Self-report questionnaires were distributed to 683 middle school students from Hubei province in China. Structural Equation Modelling was used to analyse the data. The results showed that basic psychological needs satisfaction exerted negative effects on adolescents’ depression in both a direct and an indirect way. In specific, basic psychological needs satisfaction not only directly reduced depression, but also indirectly reduced depression by the mediating role of feelings of safety, but not by rumination. Moreover, autonomy and relatedness, but not competence need satisfaction, indirectly reduced depression by the multiple mediating path from feelings of safety to rumination. The findings indicate satisfaction of basic psychological needs is important in increasing adolescents’ feelings of safety, reducing negative cognitions, and alleviating their depression level during the pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has not only raised a substantial threat to physical health and property, but also conducted a very negative effect on individuals’ mental health, leading to symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress responses [1, 2]. Especially adolescents, who are at a critical period of physical and mental development, are at higher risk of mental health problems than adults [3], such as depression frequently reported as a psychological disorder among adolescents during the pandemic [4]. Researchers found that the incidence of depressive symptoms in adolescents across 21 provinces in China reached 43.7% [5], which is significantly higher than before [6]. Therefore, adolescents’ depression in the context of the pandemic deserves more attention.

Although more help and intervention such as the government’s material support, teachers’ care, and psychologists’ service has been offered to adolescents during the pandemic, a higher prevalence of depression still exists among them. Zhou and Yao (2020) [7] suggested that the relieving effect of the above mentioned on adolescents’ mental problems depended on whether the support substantially fulfilled their basic psychological needs. According to Self-Determination Theory [8, 9], individuals’ behaviours and choices mainly derive from whether or not their basic psychological needs are satisfied. The theory proposes that the internalization of individual motivation is a natural process, which requires the support of “nutrition” to play the best function, which is the basic psychological needs (BPN) including autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Autonomy involves individuals’ need to experience volition and willingness, with which they can dominate their own behaviour; competence concerns the need to experience mastery and effectiveness when dealing with specific activities and tasks; and relatedness describes the need to belong and feel supported by others [8, 9]. When their basic needs are satisfied, individuals can interact with the environment autonomously, perceive higher levels of control and self-efficacy, and feel supported; these leads to greater well-being [10] and less depression [11], whereas failure to fulfil BPN is associated with more depression, anxiety, and other negative emotions [12, 13]. In light of this, studies had considered basic psychological need satisfaction as an important protective factor, and assessed its relation as an independent variable to mental problems [14,15,16]. Accordingly, we hypothesized that an important determinant of whether individuals experience depression during the pandemic is whether their psychological needs are fulfilled. Specifically, psychological need satisfaction may reduce the risk of adolescents’ depression [17, 18].

It is noteworthy that despite the satisfaction of the three BPN are closely interactive in adolescents’ mental status, they are unique constructs and may show different influence on adolescents’ depression. For instance, autonomy need satisfaction might be associated with greater vitality and lesser depression when implementing social distancing measures under the pandemic [14]. Hence, we will consider them as three constructs in this study when assessing the influencing mechanism of BPNs on adolescents’ depression.

Self-Determination Theory [8] also suggests that BPN satisfaction (BPNs) can affect individuals’ cognitive evaluation in stressful environments [19], which will indirectly affect depression. In fact, satisfaction of autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs help individuals to establish positive goals in a stressful environment and increase their motivation of using positive cognitive styles to cope with stressful events [20], thus may reduce negative cognition. Satisfaction of psychological needs can also directly enhance an individual’s feelings of control over a stressful environment, increase their coping efficacy, and prompt them to seek more social support [20], thereby increasing positive cognitions of the stressful environment and reduces negative rumination. Rumination refers to a negative way of thinking, which is manifested as repeatedly thinking about the painful emotion itself, the cause of the painful emotion, and various possible adverse consequences when encountering painful emotions, rather than solving the problem actively [21]. According to response styles theory [21], rumination (which is a passive and negative cognitive evaluation style) can lead to more negative emotions, make people be pessimistic about the external environment, and increase depression. Thus, rumination may be an important cognitive variable that mediates the effect of psychological need satisfaction on depression. Therefore, the satisfaction of psychological needs may inhibit ruminative thinking, thereby alleviating depression.

Furthermore, some researchers support that safety is necessary for human beings[22], which may affect their psychological outcomes [23]. Individuals who feel safe are more willing to share their traumatic experiences and emotions with others, which helps them more easily to seek support from others [24], directly alleviating their own depression [25]. Seeking support and help from others also prompts people to rethink their own negative experiences from the perspectives of others, which increases understanding of their own emotions and cognitive responses. It may also change their attention to negative experiences and help them to rethink such experiences [26]. All these factors reduce negative thinking and rumination on negative experiences, thereby alleviating depression [25]. Therefore, feelings of safety can not only directly alleviate depression, but also indirectly alleviate depression by reducing rumination.

Based on the Self-Determination Theory, it was proposed that the satisfaction of autonomy, competenceand relatedness needs, and the development of feelings of safety, can alleviate depression directly or indirectly through rumination. Moreover, according to López-Rodríguez and Hidalgo (2014) [23], there is a connection between the satisfaction of autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs and feelings of safety. For example, once an individual’s psychological needs are satisfied, they experience more certainty and control in coping with various situations, experience greater feelings of belonging, and gain more support [8, 9]. Because feelings of control, interpersonal safety, and belonging generate a sense of individual safety [27], satisfaction of an individual’s psychological needs can enhance their feelings of safety. Therefore, following this theory, we hypothesized that: autonomy, competence, and relatedness need satisfaction directly alleviates adolescents’ depression (Hypothesis 1, H1); autonomy, competence, and relatedness need satisfaction indirectly reduces depression through feelings of safety (H2a) and through rumination (H2b); autonomy, competence, and relatedness need satisfaction indirectly relieves depression by multiple mediating effects through feelings of safety via rumination (H3).

Health psychology research has recognized that psychological need satisfaction may interact with cognitive evaluation style in affecting psychological responses, but few studies have examined the combination of individual BPNs and cognitive evaluation styles to explore the mechanism by which they affect psychological responses [20]. In fact, integrating these two psychological aspects helps to understand the association between motivational and behavioural characteristics of psychological outcomes, and provides a foundation for follow-up studies. In addition, Deci and Ryan (1987) [28] have emphasized that although BPNs may affect psychological outcomes, there are differences between the effects of autonomy, competence, and relatedness need satisfaction on psychological outcomes in specific situations. For example, some studies show that competence and autonomy, but not relatedness, negatively predict depression in adolescents [29]. In contrast, Véronneau, Koestner, and Abela [30] found that only competence need satisfaction substantially alleviates depression symptoms. Therefore, whether these three kinds of psychological needs have different effects on depression needs further investigation. Moreover, compared with adults, adolescents are more likely to experience negative psychological consequences when facing major traumatic events, because the psychological development of adolescents is incomplete. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is regarded as a major traumatic event [31], we investigated the mechanism underlying the effects of autonomy, competence, and relatedness need satisfaction on depression via feelings of safety through rumination in adolescents.

Method

Participants

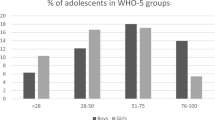

In July 2020, six months after the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic in China, we recruited adolescents by paper-pencil questionnaires from Hubei province, China. With the help of school teachers, we selected 12 classes in Grade one with no teaching activities. There were approximately 60 students in each class. Finally, 683 students were enrolled in this study. Of these, 341 (49.9%) were boys, 301 (44.1%) were girls, and 41 (6.0%) did not report their sex. The mean age was 16.06 years (standard deviation 0.56 years; range 15–18 years).

This study was approved by the research ethics committee of Hangzhou Normal University. All students in the selected classrooms attended school on the assessment date, and all agreed to participate in the investigation and completed self-report questionnaires. Participants were informed of the purpose of the study and the voluntary nature of participation before the survey. Written informed consent was obtained from all students and their guardians. Assessments were conducted under the supervision of trained psychology postgraduate students.

Measures

Pandemic exposure. We used the Epidemic Exposure Questionnaire developed by Zhen and Zhou [32] to measure the pandemic exposure of adolescents. The questionnaire comprised 10 items. A sample item was “My relatives are infected or quarantined”. Each item was scored as 0 (no) or 1 (yes); higher scores indicated more severe exposure to the pandemic.

Basic psychological need satisfaction. We used the BPNs Scale [33] to investigate the psychological need satisfaction of adolescents. The scale comprised nine items divided into three main dimensions: autonomy (e.g., “I have the rights to decide my behaviours and to express my views.”), competence (e.g., “I feel that I am a competent person.”), and relatedness need satisfaction (e.g., “I feel loved and cared for.”). Each item was scored on a 6-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 5 = completely agree). The scale had acceptable reliability (α = 0.75) in this study.

Feelings of safety. We used the revised Perceived Security Questionnaire to measure feelings of safety. The original questionnaire was developed by Liu and colleagues [34] to measure the perceived security of people affected by the Wenchuan earthquake. To measure the feelings of safety of adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic, we changed the context from ‘earthquake’ to ‘COVID-19 pandemic.’ After evaluating the items and language of the revised questionnaire by researchers in this area, we confirmed the adaptability of the revised questionnaire. The revised questionnaire comprised 10 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). A sample item was “I still feel warm since the outbreak of the pandemic.” Previous studies did similar revision and showed acceptable reliability [35]. The revised questionnaire also had acceptable reliability (α = 0.67) in this study.

Rumination. We used the rumination subscale of the Chinese revised version of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire [36] to measure the rumination of adolescents during the pandemic. The scale comprised four items scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). A sample item was “I’m addicted to the feelings and thoughts of what I’ve been through.” The scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = 0.85).

Depression. We used the Depression Scale for Children developed by Fendrich, Weissman, and Warner [37], translated and revised by Wang [38] to measure depression in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. The scale comprises 20 items scored on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = never, 3 = always). A sample item was “I feel depressed and unhappy.” Higher scores indicated more severe depression. The scale showed acceptable reliability (α = 0.79) in this study.

Data Analytical Strategies

SPSS 20.0 and Mplus 7.0 were used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis were used to examine the variable levels and the associations between variables. Structural Equation Modelling was used to analyse the mediation effect [39], testing the direct and indirect effects between BPNs and depression, and the significance of the mediation effect was tested using bias-corrected bootstrap testing [40].

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations between main variables

Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine the associations between pandemic exposure, autonomy, competence, and relatedness need satisfaction, feelings of safety, rumination, and depression. The results were shown in Table 1. Pandemic exposure was significantly and positively associated with depression (r = 0.16, p < 0.001), but significantly and negatively associated with competence need satisfaction and feelings of safety (r = -0.11, p < 0.01; r = -0.09, p < 0.05). The correlations between pandemic exposure and all other variables were not significant. The three types of need satisfaction were significantly and positively associated with feelings of safety (r = 0.39, p < 0.001; r = 0.42, p < 0.001; r = 0.49, p < 0.001), but significantly and negatively associated with depression (r = -0.38, p < 0.001; r = -0.47, p < 0.001; r = -0.50, p < 0.001). Autonomy and relatedness need satisfaction were marginally and negatively associated with rumination (r = -0.07, p < 0.1; r = -0.07, p < 0.1). Competence need satisfaction was significantly and negatively associated with rumination (r = -0.09, p < 0.05). Feelings of safety were significantly and negatively associated with rumination and depression (r = -0.20, p < 0.001; r = -0.50, p < 0.001). Rumination was significantly and positively associated with depression (r = 0.34, p < 0.001).

The mediating roles of feelings of safety and rumination

To test a mediation effect [39], we first used Structural Equation Modelling to test the direct effects of satisfaction of the three basic needs on depression. The direct model fit the data well, χ2(0) = 0.00, confirmatory fit index (CFI) = 1.00, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 1.00, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.00 (90% confidence interval [CI]: 0.00–0.00), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.00 [41]. The path analysis results showed that after controlling for pandemic exposure, autonomy, competence, and relatedness need satisfaction had direct and significant negative effects on adolescents’ depression (β = −0.16, p < 0.001; β = −0.20, p < 0.001; β = −0.32, p < 0.001), which supported H1 [42].

Then we established a multiple mediation effects model with feelings of safety and rumination as mediators, which served as a bridge in the relation between basic needs satisfaction and depression and reveals the underlying mechanism of how basic needs satisfaction affect depression. The model was established by building the paths from needs satisfaction to feelings of safety, rumination, and depression, paths from feelings of safety and rumination to depression, and path from feelings of safety to rumination (see Fig. 1). This model showed a good fit with the data, χ2(0) = 0.00, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00 (90% CI: 0.00–0.00), SRMR = 0.00. The results showed that after controlling for pandemic exposure, autonomy, competence, and relatedness need satisfaction had significant negative effects on depression (β = −0.10, p = 0.005; β = −0.17, p < 0.001; β = −0.25, p < 0.001, respectively), significant positive effects on feelings of safety (β = 0.20, p < 0.001; β = 0.11, p = 0.007; β = 0.35, p < 0.001, respectively), but non-significant effects on rumination (β = −0.003, p = 0.944; β = −0.01, p = 0.770; β = 0.05, p = 0.336, respectively). Besides, feelings of safety and rumination had significant negative effects on depression (β = −0.21, p < 0.001; β = 0.25, p < 0.001). In addition, feelings of safety had significant negative effects on rumination (β = −0.21, p < 0.001).

Finally, we examined the significance of these mediation effects using bias-corrected bootstrap analysis. If the 95% confidence interval does not include 0 a path is significant [40]. Table 2 showed the bootstrap test results. These results indicated that satisfaction of the three BPN had significant negative effects on depression by adolescents’ feelings of safety as a mediator, but not by rumination as the paths from BPNs to rumination were non-significant, therefore H2a was supported, but H2b was not. Besides, Autonomy and relatedness, but not competence need satisfaction, had indirect and negative effects on adolescents’ depression by a multiple path from feelings of safety to rumination, partially supporting H3.

Discussion

This study examined the association between BPNs, feelings of safety, rumination, and depression in adolescents during the pandemic. We focused on the mechanism underlying the effect of BPNs on depression through feelings of safety and rumination. We found that BPNs (independently of feelings of safety and rumination) significantly and directly alleviates depression. Consistent with previous study results [17], such finding supported H1 and Self-Determination Theory [9, 43]. The pandemic led to adolescents’ negative emotions, but BPNs stimulated individuals’ positive motivations to achieve goals during the pandemic [43], and increased their autonomy and selectivity, feelings of efficacy in responding to the pandemic, and feelings of group belonging. All these factors could prompt individuals to seek available resources to actively cope with negative experiences, regulate their own emotions, improve their well-being, and reduce psychological pressure [44], which ultimately mitigated depression. For example, a survey of 87 Norwegian primary school students pointed out that maintaining a positive attitude towards the pandemic restrictions would bring more well-being and positive emotions, and reduce negative emotions [45].

In order to further understand how BPNs was associated with adolescents’ depression, we examined the mediating roles of feelings of safety and rumination in the relations between BPNs and depression, and found that BPNs indirectly reduced depression by enhancing adolescents’ feelings of safety, which was consistent with H2a. During the pandemic, adolescents had been quarantined at home for a long time. They couldn’t go outside for entertainment or meeting new friends as usual, bud had to take online classes. Such drastically different study and life routines might lead to their mental health problems [46]. It was especially important that adolescents adjusted to the quarantine lives, cherished and enjoyed the time with parents, and the time when their needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness were satisfied. Satisfaction of the three BPN may increase the effectiveness of an individual’s responses to the pandemic and related experiences, and improve their confidence in coping with these types of negative experiences. In addition, individuals may also experience more support from society and greater feelings of belonging [20]. Satisfaction of these three BPN helps to increase individuals’ feelings of certainty, control, and interpersonal safety, which enhances feelings of safety. If individuals feel safe, they are more willing to share their own experiences and emotions with others. This increases the likelihood that they will seek support and help from others [24] and respond to pandemic-related experiences actively, thereby alleviating depression caused by the pandemic.

However, against H2b, satisfaction of the three BPN did not affect depression via rumination. This was mainly because the direct association between BPNs and rumination was not significant. There were two possible reasons: the complete mediating effect of feelings of safety concealed the direct effect of BPNs on rumination. Alternatively, even if BPN were satisfied during the pandemic, sudden changes in the social environment caused by the pandemic increased individuals’ uncertainty about the future, resulting in an imbalance between their ideals and reality, which may have induced rumination [47]. Therefore, the satisfaction of psychological needs did not directly reduce rumination during the pandemic.

In addition, we found that autonomy and relatedness, but not competence need satisfaction had multiple indirect and negative effects on depression via feelings of safety through rumination (See Table 2), which partially supported H3. Competence need satisfaction was less associated with feelings of safety than autonomy and relatedness need satisfaction. In fact, satisfaction of the need for autonomy may increase the autonomy of individual behaviour, increase feelings of control over the environment, and alleviate the negative effect of threat, which may substantially increase feelings of safety [48]. Satisfaction of the need for relatedness can increase feelings of belonging and the perception of social support [8, 9]. This puts individuals in a supportive, understanding, and safe environment, and may also increase their feelings of safety [25]. However, the satisfaction of competence needs mainly improves coping efficacy [9], and has a weaker effect on feelings of safety. Individuals who feel safe tend to reveal their own experiences and emotions, which helps them to view their experiences from different perspectives and reconstruct a positive understanding of themselves, others, and the world during the pandemic [26]. It also helps individuals to reduce negative rumination about pandemic-related experiences, thereby alleviating depression. Because there was a weak association between competence need satisfaction and feelings of safety, even though feelings of safety affect depression via rumination, competence need satisfaction could not affect depression via feelings of safety through rumination. In the bootstrap analysis, which extracted 2000 samples, the indirect path from competence need satisfaction to depression via feelings of safety through rumination became non-significant. These results supported Self-Determination Theory [8, 9] and indicated that satisfaction of psychological needs was important in increasing adolescents’ feelings of safety, reducing negative cognitions, and alleviating depression during the pandemic. These results could inform practical depression interventions for adolescents in the pandemic or post-pandemic periods. Such interventions should seek to satisfy adolescents’ psychological needs by providing help and support and to alleviate their depression by increasing feelings of safety and reducing negative cognitions.

Several limitations should be noted in this study. First, the cross-sectional research design was difficult to sufficiently clarify the change of associations and causality between the variables over time, therefore, future research could use a longitudinal design to investigate these questions. Second, only including a sample of adolescents exposed to COVID-19 pandemic might limit the generalizability of the current results, researchers can deepen the findings by expanding other samples in other phases of the pandemic. Third, many factors might mediate the relationship between BPNs, but current study only selected the feelings of safety and rumination according to related theories, thus more mediators can be considered in the future study. Finally, frustration of BPN represented a stronger and more threatening experience than the mere absence of its fulfilment [49], hence taking frustration of BPN into consideration would benefit our deeper understanding of adolescents’ plight under the lasting COVID-19 pandemic.

Summary

We investigated the mediators of the association of autonomy, competence, and relatedness need satisfaction with depression in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results showed that satisfaction of these three psychological needs had direct and negative effects on depression, and exerted indirect and negative effects on depression via feelings of safety. Autonomy and relatedness need satisfaction had multiple indirect and negative effects on depression via feelings of safety through rumination. These results provided important theoretical and practical implications for the follow-up research and practice on adolescent mental health.

References

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, McIntyre RS et al (2020) A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun 87:40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028

Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, Lui LMW, Gill H, Phan L et al (2020) Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J Affect Disord 277:55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

Wu S, Sun B (2021) How adaptability influences student engagement under COVID-19: Mediation effects of academic emotion [in Chinese].Contemp Educ Sci(08):87–95

Murata S, Rezeppa T, Thoma B, Marengo L, Krancevich K, Chiyka E et al (2021) The psychiatric sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic in adolescents, adults, and health care workers. Depress Anxiety 38(2):233–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23120

Zhou S, Zhang L, Wang L, Guo Z, Wang J, Chen J et al (2020) Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 29(6):749–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01541-4

Gladstone TRG, Schwartz JAJ, Pössel P, Richer AM, Buchholz KR, Rintell LS (2021) Depressive symptoms among adolescents: Testing vulnerability–stress and protective models in the context of COVID–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-021-01216-4. Child Psychiat Hum D

Zhou X, Yao B (2020) Social support and acute stress symptoms (ASSs) during the COVID-19 outbreak: Deciphering the roles of psychological needs and sense of control. Eur J Dev Psychol 11:1779494. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1779494

Deci EL, Ryan RM (2000) The “What” and “Why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq 11(4):227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2017) Self-Determination Theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation development and wellness. Guilford Press, New York, NY

Kanat-Maymon Y, Antebi A, Zilcha-Mano S (2016) Basic psychological need fulfillment in human-pet relationships and well-being. Pers Individ Differ 92:69–73. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Tang M, Wang D, Guerrien A (2020) A systematic review and meta-analysis on basic psychological need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in later life: Contributions of Self-Determination Theory. Psych J 9(1):5–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.293

Vansteenkiste M, Ryan RM (2013) On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as an unifying principle. J Psychother Integr 23(3):263–280. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032359

Wu C, Rong S, Zhu F, Chen Y, Guo Y (2018) Basic psychological need and its satisfaction [in Chinese]. Adv Psychol Sci 26(6):117–127. https://doi.org/10.1001/10.3724/SP.J.1042.2018.01063

Behzadnia B, FatahModares S (2020) Basic psychological need-satisfying activities during the COVID-19 outbreak. Appl Psychol Health Well-Being 12(4):1115–1139. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12228

Šakan D, Žuljević D, Rokvić N (2020) The role of basic psychological needs in well-being during the COVID-19 outbreak: A Self-Determination Theory perspective. Front Public Health 8:583181. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.583181

Varsamis P, Halios H, Katsanis G, Papadopoulos A (2021) The role of basic psychological needs in bullying victimisation in the family and at school. J Psychol Couns Sch 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2021.9

Emery AA, Toste JR, Heath NL (2015) The balance of intrinsic need satisfaction across contexts as a predictor of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. Motiv Emot 39(5):753–765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-015-9491-0

Wei M, Shaffer PA, Young SK, Zakalik RA (2005) Adult attachment, shame, depression, and loneliness: The mediation role of basic psychological needs satisfaction. J Couns Psychol 52(4):591–601. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.591

Skinner E, Edge K (2002) Self-determination, coping, and development. In: Deci EL, Ryan RM (eds) Handbook of self-determination research. University of Rochester Press, Rochester, NY, pp 297–337

Ntoumanis N, Edmunds J, Duda JL (2009) Understanding the coping process from a Self-Determination Theory perspective. Brit J Health Psych 14(2):249–260. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910708X349352

Nolen-Hoeksema S (1991) Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. J Abnorm Psychol 100(4):569–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.100.4.569

Sheldon KM, Elliot AJ, Kim Y, Kasser T (2001) What is satisfying about satisfying events? Testing 10 candidate psychological needs. J pers soc psychol 80(2):325–339. https://doi.org/10.1037//O022-3514.80.2.325

López-Rodríguez VA, Hidalgo A (2014) Security needs: Some considerations about its integration into the Self-Determination Theory (SDT). Dirección y Organización. 52:46–58. https://doi.org/10.37610/dyo.v0i52.446

Edmondson AC, Kramer RM, Cook KS (2004) Psychological safety, trust, and learning in organizations: A group-level lens. In: Kramer RM, Cook KS (eds) Trust and Distrust in Organizations: Dilemmas and Approaches. Russel Sage Foundation, New York, pp 239–272

Zhen R, Quan L, Zhou X (2018) How does social support relieve depression among flood victims? The contribution of feelings of safety, self-disclosure, and negative cognition. J Affect Disord 229:186–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.087

Zhou X, Wu X, Wang W, Tian Y (2018) The relation between repetitive trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder: Understanding the roles of feelings of safety and cognitive reappraisal [in Chinese]. Psychol Dev Edu 34(1):90–97. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2018.01.11

An L, Cong Z, Wang X (2004) Research of high school students’ security and the relatied factors [in Chinese]. Chin Ment Health J 18(10):717–719

Deci EL, Ryan RM (1987) The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol 53(6):1024–1037. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1024

Deng L, Xin X, Xu J (2019) Relation of anxiety and depression symptoms to parental autonomy support and basic psychological needs satisfaction in senior one students [in Chinese]. Chin Ment Health J 33(11):82–87. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2019.11.014

Véronneau M, Koestner RF, Abela JRZ (2005) Intrinsic need satisfaction and well–being in children and adolescents: An application of the Self–Determination Theory. J Soc Clin Psychol 24(2):280–292. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.24.2.280.62277

Shevlin M, Hyland P, Karatzias T (2020) Is posttraumatic stress disorder meaningful in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic? A response to Van Overmeire’s commentary on Karatzias (2020). J Trauma Stress 33 (5): 866–868. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22592

Zhen R, Zhou X (2020) Predictive factors of public anxiety under the outbreak of COVID-19 [in Chinese]. J Appl Psychol 26(2):99–108. https://doi.org/CNKI:SUN:YXNX 0.2020-02-001

Sheldon KM, Niemiec CP (2006) It’s not just the amount that counts: Balanced need satisfaction also affects well-being. J pers soc psychol 91(2):331–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.2.331

Liu L, Tang Y, Zhang J, Deng L, Lei D, Liu H (2009) The relation between perceived security and PTSD of Wenchuan Earthquake survivors [in Chinese]. Adv Psychol Sci 17(3):547–550. https://doi.org/10.1360/972009-782

Quan L, Zhen R, Yao B, Zhou X (2017) Traumatic exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder among flood victims: Testing a multiple mediating model. J Health Psychol 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317707568

Zhu X, Luo F, Yao S, Auerbach RP, Abela JRZ (2007) Reliability and validity of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire – Chinese version [in Chinese]. Chin J Clin Psychol 21(2):121–124. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1005-3611.2007.02.004

Fendrich M, Weissman MM, Warner V (1990) Screening for depressive disorder in children and adolescents: Validating the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale for children. Am J Epidemiol 131(3):538–551. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115529

Wang X (1993) Rating scales for mental health (Chinese Mental Health Journal · Supplement). China Association for Mental Health, Beijing

Cheung MWL (2007) Comparison of approaches to constructing confidence intervals for mediating effects using Structural Equation Models. Struct Equ Modeling 14(2):227–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510709336745

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2008) Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 40(3):879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Wen Z, Hou T, Herbert M (2004) Structural equation model testing: Cutoff criteria for goodness of fit indices and chi-square test [in Chinese]. Acta Psychol Sinica 36(2):186–194

Taylor AB, MacKinnon DP, Tein JY (2008) Tests of the three-path mediated effect. Organ Res Methods 11(2):241–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428107300344

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2000) The darker and brighter sides of human existence: Basic psychological needs as a unifying concept. Psychol Inq 11(4):319–338. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1104_03

Auclair-Pilote J, Lalande D, Tinawi S, Feyz M, de Guis E (2021) Satisfaction of basic psychological needs following a mild traumatic brain injury and relationships with post-concussion symptoms, anxiety, and depression. Disabil Rehabil 43(4):507–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1630858

Martiny SE, Thorsteinsen K, Parks-Stamm EJ, Olsen M, Kvalo M (2021) Children’s well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: Relationships with attitudes, family structure, and mothers’ Well-being. Eur J Dev Psychol 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2021.1948398

Commodari E, Rosa VLL (2020) Adolescents in quarantine during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: Perceived health risk, beliefs, psychological experiences and expectations for the future. Front Psychol 11:559951. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.559951

Ye B, Wu D, Im H, Liu M, Wang X, Yang Q (2020) Stressors of COVID-19 and stress consequences: The mediating role of rumination and the moderating role of psychological support. Child Youth Serv Rev 118(2):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105466

Normoyle J (1980) Locus of Control Beliefs, Territoriality and Feeling of Safety in Elderly Urban Women. Loyola University Chicago

Vansteenkiste M, Ryan RM, Soenens B (2020) Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motiv Emot 44:1–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09818-1

Funding

This study was supported by National Youth Project for National Social Sciences Fund of China (Education; CHA200259).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LS, XW, and RZ collected the data, ZL, LS, RZ, and XZ performed data analysis, ZL, LS, and RZ wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hangzhou Normal University.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Thank the teachers and students in the participating school for their time and support.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Shen, L., Wu, X. et al. Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Depression in Adolescents During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Roles of Feelings of Safety and Rumination. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 55, 219–226 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-022-01395-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-022-01395-8