Abstract

Experience of bullying may be a significant risk factor for non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). This study had three aims: to systematically investigate the association between bullying and NSSI, analyze the possible mechanisms underlying the two phenomena, and evaluate any differences between bullying victimization and bullying perpetration with respect to NSSI. A systematic search about the association between bullying victimization and perpetration and NSSI was conducted using specific databases (PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct). The following keywords were used in all database searches: "bullying" AND "NSSI" OR "peer victimization" and NSSI. The searches in PubMed, Scopus and Science Direct revealed a total of 88 articles about bullying or peer victimization and NSSI. However, only 29 met our inclusion criteria and were used for the present review. Overall, all studies examined victimization; four studies also evaluated the effects of perpetration and one included bully-victims. According to the main findings, both being a victim of bullying and perpetrating bullying may increase the risk of adverse psychological outcomes in terms of NSSI and suicidality in the short and the long run. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review to systematically evaluate the relation between bullying victimization/perpetration and NSSI. The main results support a positive association. Future research should evaluate the possible role of specific mediators/moderators of the association between experience of bullying and NSSI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) can be defined as the deliberate, self-inflicted destruction of body tissue without suicidal intent and for purposes that are not socially sanctioned, for example via cutting, burning, biting or scratching skin [1]. This definition eliminates indirect self-harm (e.g., drug abuse, eating disorders), self-injurious behaviour with suicidal intent, and socially sanctioned behaviour, such as piercing or tattooing. The 12-month prevalence of NSSI among Chinese adolescents is estimated to be 29% [2] with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 17% in adolescents in the general population and up to 74% in adolescents with psychiatric disorders [3].

NSSI represents a serious public health concern for adolescents and young adults because it is associated with poorer social relationships and greater psychosocial impairment [4], higher rates of depression and anxiety [5], impulsivity [6], substance use, axis II personality disorders and lifetime suicidal attempts [7]. Among personality disorders, borderline personality disorder seems to be the most common among those engaging in NSSI, with avoidant and paranoid personality disorders diagnosed at relatively high rates as well.

Studies have long highlighted the role of traumatic stressor exposure, including child maltreatment, in the development of NSSI [6, 8], suggesting that NSSI may be understood as a coping strategy used to regulate and alleviate acute negative affect or affective arousal. In turn, several potential mediators of the relationship between trauma and NSSI have been identified, including shame, self-criticism, pessimism, dissociation, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), impulsivity, hyperarousal, emotion dysregulation and alexithymia [6, 9]. A significant stressor in childhood with both short-term and long-term impacts is bullying victimization. We carried out this systematic review to determine if bullying victimization and bullying preparation may be related to NSSI.

Bullying is defined by Olweus [10] as an "intentional, repeated, negative (unpleasant or hurtful) behaviour by one or more persons directed against a person who has difficulty defending himself or herself" (page 125). Important features of the phenomenon are behaviour intentionality, and psychological or physical power imbalance between bully and victim. Bullying can be direct or indirect. Direct bullying—i.e., physical and/or verbal aggression—includes hitting, pushing, kicking, stealing from, threatening, taunting, intimidating or teasing the person. Indirect forms of bullying may be gossiping, slandering, sabotaging and convincing peers to exclude the person. Vandalizing and cyberbullying are further forms of the phenomenon [11]. Worldwide, just over one in three adolescents aged between 13 and 15 years’ experience bullying [12].

Bullies may exhibit co-morbid conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression and oppositional or conduct disorder, and are more likely to be exposed to abuse and domestic violence, while victims often show low self-esteem and low social competence, and are more likely to be affected by depression or anxiety. Bully-victims, who are victims themselves and bully others, have been found to have high levels of anxiety, depression, peer rejection and isolation, and often have poor problem-solving skills and poor social competencies [11].

The research to date has clearly established that exposure to bullying is a significant risk factor for the emergence of psychological difficulties and psychopathology, regardless of pre-existing mental health symptomology, genetic predisposition or family history. For example, adolescent and adult outcomes of bullying victimization in childhood include anxiety, depression and internalizing problems, somatic problems, psychotic experiences, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and completed suicide, and at the same time low academic achievement and poor social skills. Importantly, recent studies show that as a traumatic experience involving repetition and helplessness, bullying victimization is also associated with symptoms of dissociation and PTSD [13]. Bullying perpetration has also been associated with several poor outcomes in the long-term, including delinquent and violent behaviour, impulsivity, psychopathy, suicidal ideation and suicidal/self-harm behaviour, completed suicide, substance use, unemployment and poor social skills [14, 15].

To summarize, involvement in bullying, and NSSI or self-harm behaviour were clearly related to each other although the this link has been not still investigated systematically. Given that it is imperative to undestand comprehensively the clinical profiles and risk for NSSI or self-harm in subjects who have been exposed to bullying as well as the mechanisms of the association between NSSI and bullying, the present study aims to systematically investigate the association between bullying and NSSI, and analyze the paths connecting the two phenomena. Moreover, as few investigators, to our knowledge, examined the differential effects of bullying victimization/perpetration on NSSI, this study aims to evaluate any differences between bullying victimization and bullying perpetration in terms of their links to NSSI. We hypothesized that bullying would be associated with an increased risk for NSSI without considering the possible moderating/mediating rol of other risk factors.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

We adopted the "Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses" guidelines [16]. We included studies that expressly mentioned the association between bullying and NSSI. In particular, we included in our systematic review studies with samples of adolescents/young adults (10–24 years) who have been exposed to bullying victimization or perpetration and manifest NSSI. Specifically, we did not consider the role of additional mediating/moderating risk factors as this would have been beyond the scope of the present review which is simply to identify the link between bullying victimization/perpetration and NSSI. When a title or abstract seemed to describe a study eligible for inclusion, the full-text article was obtained and closely examined to assess its relevance for our work. Our exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies without abstracts or with abstracts that did not explicitly mention the association between bullying and NSSI; (2) studies that were not published in English; and (3) systematic reviews or meta-analyses. Finally, articles that used qualitative research methods were completely excluded and only the articles conducted with the quantitative method were examined.

Information Sources

We conducted a systematic search of major electronic databases in medicine and social science (PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct) for papers relevant to our research topic. We also surveyed the bibliographies of the selected articles for relevant additional studies. Overall, selected papers covered the period between 1 January 2008 and 1 January 2021. Unfortunately, a meta-analysis could not be conducted because the studies measured bullying and NSSI in different ways.

Search Terms

The following keywords were used in all database searches: "bullying" AND "NSSI" OR "peer victimization" AND “NSSI”. Studies on generic self-harm or those not explicitly reporting NSSI were not included.

Selection of Studies and Data Collection Process

Papers were examined and selected in a two-step process to minimize biases. First, five independent researchers (GC, GA, CC, LF, and JN) carried out the literature search. Any disagreement between the five reviewers was resolved by discussion with the senior reviewers (EF, MA). Subsequently, full-text articles meeting our inclusion criteria were recovered and independently reviewed by EF and MA, who discussed the features of the studies in order to decide whether to include them in the review. If there was doubt about a particular study, then that study was put aside while awaiting for more information and was carefully re-examined for possible inclusion. Any disagreement at this step was settled by discussion between reviewers. Studies written in languages other than English, or lacking quantitative analyses, were not included. Figure 1 summarizes the main results of the search strategy (i.e., identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion process) used for selecting studies.

Summary Measures

The quality of the 29 studies used for this review was assessed using the following criteria: (1) representativeness of the sample (0–2 points); (2) presence and representativeness of comparison group (0–2 points); (3) presence of follow-up (0–2 points); (4) evidence-based measures of bullying (e.g., Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire, Peer Relations Questionnaire, Peer Experiences Questionnaire or other psychometric evaluation) (0–2 points); (5) evidence-based measures of NSSI (e.g. Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviours Interview, Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory, Self-Harm Inventory or other psychometric evaluation) (0–2 points); (6) presence of raters who identified independently the presence of bullying (0–2 points); (7) presence of raters who identified independently the presence of NSSI (0–2 points); and (8) statistical evaluation of interrater reliability (0–2 points). Specifically, for representativeness of the sample we intended samples of at least 200 adolescents or young adults including both males and females who are not necessarily students.

Quality scores therefore could range from 0 to 16. Studies were differentiated according to their quality, as follows: (1) good quality (10–16 points), if most or all the criteria were satisfied or, if they were not met, the study conclusions were considered very robust; (2) moderate quality (4–9 points), if some criteria were met or, if they were not met, the study conclusions were considered robust; and (3) low quality (0–3 points), where few criteria were met or the conclusions were not considered robust.

Results

Study Sample

The searches in PubMed, Scopus and Science Direct revealed a total of 89 possibly relevant articles about bullying perpetration or victimization and NSSI. Overall, for bullying and NSSI, the search in PubMed generated 20 articles, and the search in Scopus generated 24 articles; the search in Science Direct generated 5 articles. For victimization and NSSI, the search in Pubmed generated 14 articles, the search in Scopus generated 16 articles, and the search in Science Direct generated 4 articles. Moreover, we extracted another 6 studies from the reference lists of these articles. Out of all these, 60 were excluded because they were duplicates, or were without an abstract, or had an abstract that did not explicitly mention NSSI and bullying or victimization, or were not written in English, or were on self-mutilation or self-harm and not NSSI, or did not use a quantitative analysis. A total of 29 studies met our inclusion criteria and were therefore used for the present review.

Study Types and Sample Characteristics

Overall, 20 cross-sectional studies including a total of 37,012 individuals, 8 longitudinal follow-up studies including 7379 individuals, and 1 retrospective study including 7,048 individuals were considered. Samples were mostly non-clinical, except for one study with major depressive disorder (MDD) and dysthymia patients, three studies with psychiatric patients and one study with ADHD patients. For the most part, subjects were adolescents or young adults, except for one study which was with adults.

Study Quality Assessment

According to our quality score system, the mean quality score of the 20 cross-sectional studies was 4.2; the mean score of the 8 longitudinal studies was 5.25; the quality score of the retrospective study was 4. The most relevant characteristics of the studies included in the present review are summarized in Table 1.

Studies Showing an Association Between Bullying/peer Victimization and NSSI

The majority of the studies in our review showed links, especially for bullying victimization. For example, in the longitudinal study of Giletta et al. [17], after accounting for depressive symptoms, peer victimization differentiated adolescents in the high trajectory of suicide ideation and NSSI from those in the low and moderate trajectories of suicide ideation and NSSI. In the clinical study of Vergara et al. [18] which explicitly tested the roles of both victimization and perpetration, bullying victimization, but not perpetration, was uniquely associated with the frequency of recent NSSI thoughts and behaviours. Interestingly, however, perpetration was significantly associated with the number of suicide attempts in the past month. There was also some evidence for the importance of considering type of victimization. For example, overt but not relational victimization was significantly correlated with NSSI at baseline, for boys, in the sample of Heilbron et al. [19]. It is important to note however that most studies in our review explored bullying victimization/perpetration alongside other putative risk factors, and we discuss these studies in the next section. Some of them also investigated mediators and moderators (which, broadly speaking, index social support) of the association between bullying victimization/perpetration and NSSI. We discuss these in detail as well.

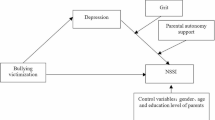

The Role of Other Putative Risk Factors

Peer victimization, alexithymia, depression, anxiety, impulsivity and lower mindfulness were all risk factors for NSSI, whereas self-compassion and higher self-esteem were protective factors in Garisch and Wilson’s [5] study. Relatedly, social self-confidence, intended as social self-worth and perceived social-self competence, was, when low, a risk factor of NSSI onset in the study of Victor et al. [20]. Other risk factors were peer victimization, and, for girls, harsh parental punishment. Self-criticism and depressive symptoms mediated the relationship between peer victimization and NSSI in the study of Xavier et al. [21].

The evidence for the independent role of depressive symptoms however is not consistent. These were not significantly associated with NSSI in the study of Mossige et al. [22], while physical and non-physical abuse by peers was. Conversely, the role of impulsivity was important rather consistently. For example, both impulsivity and bullying victimization were significant predictors of NSSI in the studies of Bakken and Gunter [23] and Keenan et al. [24]. In the latter study, decreases in assertiveness during childhood but also initial levels of self-reported depression were associated with later risk for NSSI. Impulsivity predicted NSSI in the longitudinal study of Meza et al. [25], and peer victimization partially mediated their relationship. Also consistent was the evidence for the role of exposure to and response to trauma. For example, PTSD was highlighted as a risk factor for NSSI by Christoffersen et al. [26] and Dhingra et al. [27]. Relatedly, alexithymia, potentially associated with trauma, was found to be associated with NSSI by Garisch and Wilson [5]. Stressful life events moderated the significant relationship between peer victimization and NSSI in the study of Wang and Liu [28], and depression mediated this association but only among girls.

There is also emerging evidence that the effects of these, and other related, putative risk factors may change by sexual orientation. In the study of DeCamp and Bakken [29], peer victimization, fighting, substance use, sexual behaviour, depression, and unhealthy dieting behaviours were generally associated with NSSI and suicidal ideation. The association between peer victimization and NSSI was not significant for sexual minority youth, although McCauley et al. [30] found that, when adjusted for demographics and exposure to childhood adversities, peer victimization remained a significant predictor of NSSI only in sexual minority adolescents.

The Role of Social Support

In the study of Giletta et al. [17], friend support and friendlessness distinguished between the high and low and between the moderate and low NSSI trajectories, respectively. Social connectedness and support from both parents and other adults were significant protective factors in both studies by Taliaferro et al. [31, 32] on sexual minority youth. In Taliaferro et al.’s [32] study showing a significant association between bullying victimization and NSSI in transgender/gender non-conforming youth, bullying perpetration differentiated the ‘NSSI group’ from the ‘no self-harm group’, good relationships with parents and non-parental adults constituted a protective factor, whereas mental health problems, depression and being teased because of gender expression were risk factors. In an earlier study, Taliaferro et al. [31] found similar results for bisexual youth questioning their sexual orientation, but not for homosexual youth: social connectedness moderated the relationship between risk factors and NSSI/suicidality, while depressive symptomatology was a strong risk factor. Earlier, Christoffersen et al. [26] found that the effect of bullying victimization was partially mediated by generic social support, and Giletta et al. [33] found that feeling unsupported by one’s family was related to risk of reporting NSSI independently of peer victimization and depressive symptoms.

There is much evidence for the moderating role of social support as well. Family cohesion and self-compassion moderated the relationship between bullying victimization and NSSI in the study of Jiang et al. [34]. In the study of Alfonso et al. [35], high belief in life possibilities represented a protective factor for NSSI and being bullied a risk factor. Parental monitoring was not a protective factor for NSSI in the sample of Jantzer and colleagues [36], while being a victim of bullying, especially social and cyber bullying, had particularly strong relationships with occasional and repetitive NSSI. Parental support, a different and more affective component of the parent–child relationship, partially moderated the association between bullying victimization and NSSI in the study of Claes et al. [37], while depressive mood partially mediated it. The role of nonfamilial support as a moderator was highlighted in two studies. Esposito et al. [38] found that a specific form of lack of social support, i.e. peer rejection, interacted with bullying victimization on the probability of engagement in NSSI, although being a bully increased the probability of engaging in NSSI independently of peer rejection. Hilt et al. [39] had earlier shown that quality of peer communication moderated the relationship between peer victimization and engaging in NSSI for both positive social reinforcement (i.e., getting attention) and negative social purposes (i.e., escape from interpersonal task demands). Finally, Noble et al. [40] suggested that social support from the broader environment, i.e., trust in school staff, was a protective factor for NSSI, while being bullied was a risk factor. Overall, only one study [36] was related to cyberbullying victimization which showed an especially strong relationship with repetitive NSSI.

Studies Not Showing an Association Between Bullying/peer Victimization and NSSI

The few studies showing no links are all on clinical samples. In a study conducted on the relatives of patients with bipolar disorder, Stewart et al. [41] found that being bullied was not significantly associated with lifetime NSSI, but mood disorder and substance use disorder were. In a clinical sample of adolescents with MDD and dysthymia, Stewart et al. [42] found that peer victimization was not associated with NSSI in the past month, but different subtypes of peer victimization were associated with suicide plans and attempts. In the clinical sample of girls studied by Adrian et al. [43], peer victimization was not predictive of NSSI in the previous month after controlling for depression severity. There were, instead, significant effects for emotion dysregulation and internalizing psychopathology.

Discussion

Most of the studies considered mediating/moderating factors, with several focusing on the role of the broader social context, suggesting that the broader social context is important for understanding both NSSI and bullying. For example, we included only one study related to cyberbullying [36] as this study differentiating the various subtypes of bullying [36], social and cyberbullying demonstrated particularly serious impacts. With respect to the evidence about the role of the social context in the relationship between bullying and NSSI, this may be best discussed by level. At the level of the peer group, for instance, peer support, friend support [17], social connectedness [32], generic social support [26], and absence of peer rejection [38] were all found to be protective factors, and in some cases partially mediated the effect of being bullied on NSSI. In the study by Hilt et al. [39], peer victimization was associated with engaging in NSSI for social reinforcement, and quality of peer communication moderated this relationship. At the level of the family context, parent connectedness [31], family support [33] family cohesion (Jiang et al., 2016) and parent support [37] were highlighted as important factors, and the latter two factors moderated the relationship between peer victimization and NSSI. Finally, at the level of the broader environment, the quality of relationships with non-parental adults [31], trust in school staff [40], and perceived school safety [31] were identified as important protective factors.

Of course, NSSI has long been recognized as serving as an emotion-regulation strategy as well, regardless of any social functions it may serve. Indeed, most of the studies we reviewed suggest strong links with depressive symptomatology which in fact frequently mediates the relationship between bullying and NSSI. Some studies, similarly to Giletta et al. [17], found that the relationship between bullying and NSSI persisted after accounting for depressive symptoms, while others, such as Adrian et al.’s [42], found that depression explained away the association, and Wang and Liu [28] found that the relationship was mediated by depression only among girls. The importance of viewing NSSI under this light is suggested by studies showing protection or mediation by the following factors: self-compassion [34], belief in life possibilities [35], self-esteem [5], social self-confidence [20], and low self-criticism [21].

Another interesting pattern that emerged in our review was that impulsivity was likely very important in the association we examined. Some studies [23, 29] found that NSSI was associated with several other impulsive and risky behaviours. Conversely, the role of self-control was highlighted by both Keenan et al. [24] and Meza et al. [25]. Interestingly, based on the study of Meza et al. (2016), peer victimization mediated the relationship between poor self-control and NSSI, suggesting that peer victimization may be itself influenced by impulsivity.

Main Strengths and Limitations/shortcomings

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review to systematically evaluate the relationship between bullying victimization and perpetration and NSSI. However, our results should be considered in the light of the following limitations. First, as anticipated in the Methods section we could not conduct a meta-analysis because the studies measured bullying and NSSI in different ways. Second, the inclusion/exclusion of specific studies may be influenced by our own points of view and experience. Third, findings may have been hampered by recall bias. Fourth, important aspects of bullying such as severity, duration, intensity, and age at occurrence were not taken into account in all studies; these should be considered routinely in future studies. Fifth, in some studies NSSI was measured as a lifetime occurrence while in others it was measured over a very narrow and very specific time window (e.g., in the past month). Sixth, in some studies protective and risk factors were treated as confounders and in others they were specifically tested as mediators or moderators. Seventh, in some studies NSSI was evaluated controlling for depressive symptoms, demographics or adversity exposures, while in others it was not. Finally, some studies did not include comparison groups, or used special or clinical samples, or were single-gender investigations.

In conclusion, the results of this systematic review support the positive association between bullying victimization/perpetration and NSSI, and suggest the existence of a relationship between bullying victimization/perpetration and suicidal behavior which is linked with specific biological abnormalities [44, 45]. Importantly, intervention strategies might be implemented based on the mentioned link between bullying victimization and NSSI with school interventions that should provide regularly psychological counseling to guarantee the early and appropriate identification of emotional distress in students. Overall, school-based programs should perform timely anti-bullying programs to actively reduce the negative burden of bullying with both parents and teachers should provide attention and survaillance to adolescents and young adults in order to attenuate peer victimization and eventually perpetration experiences. Finally, future interventions need to be designed to prevent peer victimization even minimizing the influence of stressors associated with impairments of parent–child relationships and dysregulated coping strategies [28].

Future research should evaluate the role of specific mediators and moderators of these associations.

Summary

The present review aimed to explore the association between bullying perpetration/victimization and NSSI. We examined 29 studies investigating this relationship. All the studies examined victimization; 4 studies also evaluated the effects of perpetration and 1 studied bully-victims. According to the main findings, both bullying perpetration and bullying victimization increase the risk of NSSI, in line with other studies showing both being risk factors for adverse outcomes, although the evidence for the role of victimization was more consistent. Bullying perpetration was associated with NSSI or suicide attempts only. The bullying perpetration/NSSI relationship was partially mediated by depression in the study of Claes and colleagues [37], and, importantly, was independent of peer rejection in the sample of Esposito and colleagues [38], although in that study bully-victims were significantly more involved in NSSI only at high levels of peer rejection. The association between bullying perpetration and NSSI, and particularly suicide attempts, may be related to impulsivity, anger (turned against the self or others), sensation-seeking or self-punishment. These findings may help to early detect and rapidly recognize those who experienced bullying as a specific group at risk for NSSI and suicidal behaviours.

References

International Society for the Study of Self-Injury (2007) Definition of non-suicidal self-injury. http://www.itriples.org/isss-aboutself-i.html. Accessed 28 Mar 2020.

Tang J, Li G, Chen B, Huang Z, Zhang Y, Chang H, Wu C, Ma X, Wang J, Yu Y (2018) Prevalence of and risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury in rural China: results from a nationwide survey in China. J Affect Disord 226:188–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.051

Olsen MH, Morthorst B, Pagsberg AK, Heinrichsen M, Møhl B, Rubæk L, Bjureberg J, Simonsson O, Lindschou J, Gluud C, Jakobsen JC (2021) An Internet-based emotion regulation intervention versus no intervention for non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: a statistical analysis plan for a feasibility randomised clinical trial. Trials 22:456. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-021-05406-2

Martin J, Bureau JF, Cloutier P, Lafontaine MF (2011) A comparison of invalidating family environment characteristics between university students engaging in self-injurious thoughts & actions and non-self-injuring university students. J Youth Adolesc 40:1477–1488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9643-9

Garisch JA, Wilson MS (2015) Prevalence, correlates, and prospective predictors of non-suicidal self-injury among New Zealand adolescents: cross-sectional and longitudinal survey data. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 9:28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-015-0055-6

Ford JD, Gómez JM (2015) The relationship of psychological trauma and dissociative and posttraumatic stress disorders to nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidality: a review. J Trauma Dissociation 16:232–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2015.989563

Nock MK, Joiner TE Jr, Gordon KH, Lloyd-Richardson E, Prinstein MJ (2006) Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Res 144:65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010

Serafini G, Canepa G, Adavastro G, Nebbia J, Belvederi Murri M, Erbuto D, Pocai B, Fiorillo A, Pompili M, Flouri E, Amore M (2017) The Relationship between childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry 8:149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00149

De Berardis D, Fornaro M, Orsolini L, Valchera A, Carano A, Vellante F, Perna G, Serafini G, Gonda X, Pompili M, Martinotti G, Di Giannantonio M (2017) Alexithymia and suicide risk in psychiatric disorders: a mini-review. Front Psychiatry 8:148. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00148

Olweus D, Limber SP (2010) Bullying in school: evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus bullying prevention program. Am J Orthopsychiatry 80:124–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01015.x

Shetgiri R (2013) Bullying and victimization among children. Adv Pediatr 60:33–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yapd.2013.04.004

UNICEF UNCsF (2018) An Everyday Lesson #ENDviolence in schools. NY, USA. https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/An_Everyday_Lesson-ENDviolence_in_Schools.pdf. Accessed 28 Mar 2020.

Plexousakis SS, Kourkoutas E, Giovazolias T, Chatira K, Nikolopoulos D (2019) School bullying and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms: the role of parental bonding. Front Public Health 7:75. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00075

Wolke D, Lereya ST (2015) Long-term effects of bullying. Arch Dis Child 100:879–885. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2014-306667

Klomek AB, Sourander A, Niemela S, Kumpulainen K, Piha J, Tamminen T, Almqvist F, Gould MS (2009) Childhood bullying behaviors as a risk for suicide attempts and completed suicides: a population-based birth cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48:254–261. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e318196b91f

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 151:W65-94. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

Giletta M, Prinstein MJ, Abela JR, Gibb BE (2015) Trajectories of suicide ideation and non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents in mainland china: peer predictors, joint development, and risk for suicide attempts. J Consult Clin Psychol 83:265–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038652

Vergara GA, Stewart JG, Cosby EA, Lincoln SH, Auerbach RP (2019) Non-Suicidal self-injury and suicide in depressed adolescents: impact of peer victimization and bullying. J Affect Disord 245:744–749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.084

Heilbron N, Prinstein MJ (2010) Adolescent peer victimization, peer status, suicidal ideation, and nonsuicidal self-injury: examining concurrent and longitudinal associations. Wayne State Univ Press 2010:388–419. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.0.0049

Victor S, Hipwell AE, Stepp SD, Scott LN (2019) Parent and peer relationships as longitudinal predictors of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury onset. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 13:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-018-0261-0

Xavier A, Pinto Gouveia J, Cunha M (2016) Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence: the role of shame, self-criticism and fear of self-compassion. Child Youth Care Forum 45:571–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-016-9346-1

Mossige S, Huang L, Straiton M, Roen K (2016) Suicidal ideation and self-harm among youths in Norway: associations with verbal, physical and sexual abuse. Child Fam Soc Work 21:166–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12126

Bakken NW, Gunter WD (2012) Self-cutting and suicidal ideation among adolescents: gender differences in the causes and correlates of self-injury. Deviant Behav 33:339–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2011.584054

Keenan K, Hipwell AE, Stepp SD, Wroblesk K (2014) Testing an equifinality model of nonsuicidal self-injury among early adolescent girls. Dev Psychopathol 26:851–862. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579414000431

Meza JI, Owens EB, Hinshaw SP (2016) Response inhibition, peer preference and victimization, and self-harm: longitudinal associations in young adult women with and without ADHD. J Abnorm Child Psychol 44(2):323–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0036-5

Christoffersen MN, Møhla B, DePanfilisc D, Vammenda KS (2015) Non-suicidal self-injury—does social support make a difference? An epidemiological investigation of a Danish national sample. Child Abuse Negl 44:106–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.10.023

Dhingra K, Boduszek D, Sharratt K (2015) Victimization profiles, non-suicidal self-injury, suicide attempt, and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomology: application of latent class analysis. J Interpers Violence 31:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515576967

Wang Q, Liu X (2019) Peer victimization, depressive symptoms and non-suicidal self-injury behavior in Chinese migrant children: the roles of gender and stressful life events. Psychol Res Behav Manag 12:661–673. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S215246

DeCamp W, Bakken NW (2016) Self-injury, suicide ideation, and sexual orientation: differences in causes and correlates among high school students. J Inj Violence Res 8:15–24. https://doi.org/10.5249/jivr.v8i1.545

McCauley HL, Montano G, Miller E (2016) Bullying and childhood adversity as predictors of non-suicidal self-injury among sexual minority adolescents in healthy Allegheny teen survey. Poster Abstracts/58:S86eS118.

Taliaferro LA, McMorris BJ, Rider GN, Eisenberg ME (2018) Risk and protective factors for self-harm in a population-based sample of transgender youth. Arch Suicide Res 23:1–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2018.1430639

Taliaferro LA, Muehlenkamp JJ (2017) Nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidality among sexual minority youth: risk factors and protective connectedness factors. Acad Pediatr 17:715–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.11.002

Giletta M, Scholteb RHJ, Engelsb RCME, Ciairanoa S, Prinsteinc MJ (2012) Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: a cross-national study of community samples from Italy, the Netherlands and the United States. Psychiatry Res 197:66–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.02.009

Jiang Y, You J, Hou Y, Du C, Lin MP, Zheng X, Ma C (2016) Buffering the effects of peer victimization on adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: the role of self-compassion and family cohesion. J Adolesc 53:107–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.09.005

Alfonso ML, Kaur R (2012) Self-injury among early adolescents: identifying segments protected and at risk. J Sch Health 82:537–547. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2012.00734.x

Jantzer V, Haffner J, Parzer P, Resch F, Kaess M (2015) Does parental monitoring moderate therelationship between bullying and adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior? A community-based self-report study of adolescents in Germany. BMC Public Health 15:583. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1940-x

Claes L, Luyckx K, Baetens I, Van de Ven M, Witteman C (2015) Bullying and victimization, depressive mood, and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: the moderating role of parental support. J Child Fam Stud 24:3363–3371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0138-2

Esposito C, Bacchini D, Affuso G (2019) Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and its relationships with school bullying and peer rejection. Psychiatry Res 274:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.018

Hilt LM, Cha CB, Nolen-Hoeksema S (2008) Nonsuicidal self-injury in young adolescent girls: moderators of the distress-function relationship. J Consult Clin Psychol 76:63–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.63

Noble RN, Sornberger MJ, Toste JR, Heath NL, McLouth R (2011) Safety first: the role of trust and school safety in non-suicidal self-injury. McGill J Educ/Revue des sciences de l’éducation de McGill 46:423–441. https://doi.org/10.7202/1009175ar

Stewart JG, Valeri L, Esposito EC, Auerbach RP (2018) Peer victimization and suicidal thoughts and behaviors in depressed adolescents. Abnorm Child Psychol 46:581–596. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0304-7

Adrian M, Zeman J, Erdley C, Whitlock K, Sim L (2019) Trajectories of non-suicidal self-injury in adolescent girls following inpatient hospitalization. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 24:831–846. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104519839732

Baiden P, Stewart SL, Fallon B (2017) The mediating effect of depressive symptoms onthe relationship between bullying victimization andnon-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: findings from community and inpatient mentalhealth settings in Ontario, Canada. Psychiatry Res 255:238–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.018

Pompili M, Gibiino S, Innamorati M, Serafini G, Del Casale A, De Risio L, Palermo M, Montebovi F, Campi S, De Luca V, Sher L, Tatarelli R, Biondi M, Duval F, Serretti A, Girardi P (2012) Prolactin and thyroid hormone levels are associated with suicide attempts in psychiatric patients. Psychiatry Res 200:389–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.05.010

Pompili M, Shrivastava A, Serafini G, Innamorati M, Milelli M, Erbuto D, Ricci F, Lamis DA, Scocco P, Amore M, Lester D, Girardi P (2013) Bereavement after the suicide of a significant other. Indian J Psychiatry 55:256–263. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.117145

Wilcox HC, Fullerton JM, Glowinski AL, Benke K, Kamali M, Hulvershorn LA, Stapp EK, Edenberg HJ, Roberts GMP, Ghaziuddin N, Fisher C, Brucksch C, Frankland A, Toma C, Shaw AD, Mitchell PB, Nurnberger JI (2017) Traumatic stress interacts with bipolar disorder genetic risk to increase risk for suicide attempts. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 56:1073–1080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.09.428

Acknowledgements

This work was developed within the framework of the DINOGMI Department of Excellence of MIUR 2018-2022 (Law 232/2016).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Genova within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each author substantially contributed to the paper. GS conceived and discussed the study hypothesis and wrote the main part of the paper. GC, GA, CC, JN, and MF carried out the methodological search on the research topic, provided help in selecting papers, contributed to reviewing the literature and added contributions to the methodology and the discussion sections. AAg and AAm contributed with draft preparation and writing—review and editing. MA and EF provided the most intellectual component and supervised the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Serafini, G., Aguglia, A., Amerio, A. et al. The Relationship Between Bullying Victimization and Perpetration and Non-suicidal Self-injury: A Systematic Review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 54, 154–175 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-021-01231-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-021-01231-5