Abstract

The aim of this study is to examine emotional school engagement and psychiatric symptoms among 6–9-year-old children with an immigrant background (n = 148) in their first years of school compared to children with a Finnish native background (n = 2430). The analyzed data consisted of emotional school engagement measures completed by children and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaires completed by both parents and teachers. Children with an immigrant background had lower self-reported emotional school engagement than children with a native background with reference to less courage to talk about their thoughts in the class and more often felt loneliness. Further, they reported that they had more often been bullies and seen bullying in the class. Children with an immigrant background had more emotional symptoms and peer problems reported by parents than children with a native background. However, teachers did not report any significant differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent evidence from the OECD Reviews of Migrant Education shows that immigrant adolescents are at risk of poor school success [1]. School success, in turn, is related to later work success and a lower rate of socioeconomic disadvantages and can thus be described as an indicator of current and future adaptive success of immigrant children [2]. In many cases, problems relating to poorer school success have their origin already in preadolescent years and it has been shown that weak school engagement and poor mental health early in the school career can predict later similar adverse outcomes [3, 4]. Consequently, it is important to improve mental health and strengthen the school engagement of immigrant children as early as possible to avoid possible negative outcomes. The majority of the European studies in the area of school engagement and mental health of immigrant children and adolescents focus on adolescents [5]. However, the first years of school are a crucial developmental period with distinct developmental tasks from those of adolescence [6]. In this article, the term “child” refers to a person under the age of 13 and “adolescent” refers to persons from 13–18 years of age. Despite the aforementioned knowledge, little information is available on school engagement and the mental health of children with an immigrant background in their first years of school in Europe [5].

School engagement is a broad concept that has been analyzed in several ways [7]. One approach is to divide it into emotional, behavioral and cognitive engagement [7, 8]: The emotional engagement describes the extent of children’s positive and negative reactions to school, teacher, and activities. The behavioral engagement encompasses participation in academic activities and conduct. The cognitive engagement generally refers to motivation to master learning tasks. Immigrant adolescents have been shown to have a weaker emotional school engagement compared to natives [9]. For children with an immigrant background, the emotional engagement can be regarded especially crucial considering that children who have positive feelings towards school are likely to succeed better in socio-cultural adaptation and coping with negative emotions [10, 11]. Thus in the present study we focused on the emotional aspect of school engagement.

The emotional school engagement is inversely related to emotional problems [12]. It has been proposed that emotionally engaged adolescents are protected from emotional problems by supportive relationships with teachers and peers [12, 13]. In adolescence, school engagement is generally described to decline during the adolescence years [12, 14], yet the majority of adolescents follow stable trajectories from moderate to very high levels of school engagement [15]. Immigrant adolescents seem to be at particular risk for a declining pattern of school engagement [2, 12]. It has been suggested that immigrant adolescents disengage from school to protect themselves from failures in school success [16].

The previous literature gives mixed results for the mental health status of immigrant children and adolescents. They have been reported to display either more [17,18,19,20] or fewer [21,22,23] psychiatric symptoms than the general population. These two perspectives are called migration morbidity and the immigrant paradox, respectively. From the migration morbidity perspective, immigrants compared to natives display lower mental health and overall adjustment including school success, whereas from the immigrant paradox perspective, immigrants display more positive outcomes than natives [5]. These contradictory results are considered to be associated with differences in migration background, ethnic minority position, cultural background, age, host population, and informants [24, 25]. A recent meta-analysis that combined the results of 51 studies reporting internalizing, externalizing and academic outcomes among immigrant children and adolescents in Europe found that the migration morbidity was better supported than the immigrant paradox [5]. To summarize, immigrant children and adolescents seem to have poorer mental health than natives [17, 18, 26, 27].

Only few European studies have been published on the psychiatric symptoms and the school engagement of children with an immigrant background addressing specifically pre-pubertal school children. In an Italian study, Dimitrova and Chasiotis [28] studied the association of immigrant status with psychosocial adjustment in Albanian and Serbian immigrants compared to Slovene and Italian native children. They found that 7–12-year-old immigrant children in Italy reported lower levels of emotional instability and aggression than native children, but these differences were not reported by teachers. A Swiss study, by von Grünigen et al. [29] showed that 5–6-year-old immigrant children were less accepted by peers and were more often victimized than their Swiss peers. Atzaba-Poria et al. [19] investigated the adjustment of 7–9-year-old Indian children living in Britain. Parents of the Indian children reported more internalizing problems in their children than British parents. No significant differences were found for externalizing or total problem behavior.

Finland has a relatively short history as an immigrant receiving country and the number of immigrants remains small [30]; in 2017, there were 384,000 (7.0%) individuals for whom either both parents or the only known parent had been born abroad [31]. However, Finland is one of the countries where immigrant adolescents are at particular risk of failing to achieve basic academic proficiency: They are more than twice as likely as adolescents without an immigrant background to fail if they have personal migration experience [1]. The adaptation and success of these immigrant generations are important for the development and stability of the country [1, 2]. Considering that adolescents’ academic proficiency is associated with school engagement early on in their school career, it is of utmost importance to study early school engagement in the first years of school [32]. The aim of this study is to examine self-reported emotional school engagement and psychiatric symptoms reported by both parents and teachers among 6–9-year-old children with an immigrant background in the first years of school compared to children with a Finnish native background.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

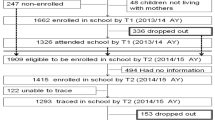

The data used was from a cluster randomized controlled trial of “Together at School” intervention program on children’s socio-emotional skills, carried out by the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL) during 2013–2014. A detailed description of the trial of “Together at School” intervention program and its data collection methodology has been reported elsewhere [33]. All Finnish primary schools were invited to participate in the study on the condition that the school had a minimum of two teachers who agreed to participate for the whole study period of two school years, and who were teaching the first, second or third grades. The data includes 79 Finnish primary schools with 3704 children [33].

Briefly, the cluster randomized controlled trial of “Together at School” was designed to evaluate children’s socio-emotional skills and mental health as primary outcomes, and related underlying mechanisms along with school and family-related factors as secondary outcomes. The informants consisted of children, parents, teachers and principals. All parents received an information letter regarding the intervention program and the aims of the study. The parents were informed about the voluntary nature of the participation in the data collection and a consent form for data collection was included in the information letter. The teachers and principals consented by agreement. The study protocol of “Together at school” intervention program was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare in Helsinki, Finland (27.9.2012) [33].

For the present analysis, the data collected from participants at the baseline in autumn 2013 was analyzed. Parents of altogether 2610 children participated at baseline and of these 2578 provided information on the question of their native language. The analyzed data consisted of the questions of emotional school engagement completed by the children themselves (n = 2353) and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaires (SDQ) completed by both parents (n = 2578) and teachers (n = 2376). A child with an immigrant background was defined as a child who had at least one parent with a foreign native language. The domestic languages are Finnish and Swedish. Of the 2578 children, 113 (4.4%) had one parent with a foreign native language and 35 (1.4%) had two parents with a foreign native language. A total of 2430 (94.3%) children had both parents with Finnish or Swedish as their native language. There were 974 children in the first grade (37.8%), 999 in the second grade (38.8%) and 605 (23.5%) children in the third grade. In Finland, first to third grade beginners normally cover children from ages 6 to 9 [34].

Measures

Demographic Details

The socio-demographic background information used were gender, school grade, family structure, mother’s basic educational level, parents’ employment status and the family’s self-reported economic situation. Family structure was composed of four categories: nuclear family, single parent family, blended family and other. Family structure was divided into two categories: nuclear family and other. Mother’s basic education was composed of three categories: lower than primary school, primary school and upper secondary school. Mother’s basic education was grouped into two categories: primary school or less and upper secondary school. Parents’ employment status was composed of seven categories: employed, entrepreneur, unemployed, disabled, stay-at-home parent, maternity or nursing leave and student. Parents’ employment status was grouped into two categories: unemployed or disabled and other. Parents reported the family’s economic situation. Parents estimated how easy or difficult it was to cover their living expenses with their income on a six-point scale. The family’s economic situation was grouped into two categories: satisfactory and difficult.

Self-reported Emotional School Engagement

Emotional school engagement was measured with a questionnaire specifically developed for the “Together at School” trial to explore the different aspects of emotional school engagement in a way that is comprehensible for small children. The statements of the questionnaire were created based on face validity while including the most widely applied aspects of emotional school engagement [35,36,37]. The children were asked to answer 14 statements with respect to school on a three-point scale. The statements measured emotional school engagement covering the child’s perceptions of the classroom atmosphere, their relationship with the teacher, their educational achievement, their sense of belonging at school, and bullying (see Table 2).

The Prevalence of Psychiatric Symptoms

The SDQ is widely used internationally and consists of a 25-item questionnaire to assess children’s psychiatric symptoms in five sub-scales: hyperactivity, emotional symptoms, conduct problems, problems with peers, and prosocial behavior [38, 39]. Separate questionnaires were completed by both teachers and parents. The SDQ and the background information form were available in Finnish and Swedish, and in the most spoken foreign languages in Finland: Albanian, Arabic, Chinese, English, Estonian, Russian, and Somali [33]. The Finnish version of SDQ has shown adequate psychometric properties [40].

Statistical Analysis

Socio-demographic characteristics and emotional school engagement were reported in frequencies separately for the two groups and comparison were tested using Pearson Chi-Square statistic. As the data used was clustered within schools and school class levels, multilevel (mixed) models were used to analyze associations between immigrant background and the outcome variables. The variance component in outcomes due to the school level was shown to be non-significant, and therefore the school level was excluded from the consecutive analysis. Analyses were conducted first with only the immigrant background as the independent variable (univariate) and this was followed by adjusting for socio-demographic background variables (multivariate), including gender, school grade, family structure, mother’s basic education, father’s employment status, mother’s employment status and family’s economic situation. The associations of immigrant background and emotional school engagement have been presented as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals obtained from generalized linear mixed models. Analyses on parent and teacher-reported SDQ were done using linear mixed models from which the estimated marginal means and their 95% confidence intervals as well as fixed effects estimates for immigrant background have been reported. Regarding the linear mixed models, three (out of 12) analyses had problems in estimation, and these (indicated in Table 4) were analyzed using ANOVA (i.e. not taking into account the clustering of data). The level for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software version 25.

Results

Participants

The background characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. There were fewer nuclear families in the immigrant background group (55.4%) compared to natives (76.7%). Parents’ unemployment or inability to work was more common in the immigrant background group among both fathers (11.5%) and mothers (17.6%) compared to natives (5.4% and 6.4%, respectively). Family’s subjective difficulty to cover expenses was greater in the immigrant background group (38.5%) than in the native background group (23.3%).

Emotional School Engagement

The frequencies of responses to the statements of emotional school engagement between the groups are reported in Table 2, and Table 3 shows results from the generalized linear mixed models analyzing these associations. In the unadjusted model, children with an immigrant background had less courage to talk about their thoughts in the class (Disagree p = 0.018, Neither agree or disagree p = 0.011), felt lonely more often (Disagree p = 0.001), had at least one friend in the class less often (Disagree p = 0.046) and they had bullied someone in their class more often (Disagree p = 0.001, Neither agree or disagree p = 0.044). These associations remained significant with the exception of ‘I have at least one friend in the class’ (p = 0.065), even when adjusted with socio-demographic factors. Additionally, in the adjusted model children with an immigrant background had more often seen someone in their class being bullied (Neither agree or disagree p = 0.049).

Psychiatric Symptoms

Table 4 shows associations between immigrant background and psychiatric symptoms reported by parents and teachers from linear mixed models. Parents in the immigrant background group reported more emotional symptoms (p < 0.001) and peer problems (p = 0.001) in their children than parents in the native background group. Additionally, parents in the immigrant background group reported higher scores for SDQ total difficulties in their children than the comparison group (p = 0.002). In the adjusted models these associations remained significant with the exception of SDQ total difficulties (p = 0.088). Teachers did not report any significant differences in psychiatric symptoms between the groups.

Discussion

This study showed that children with an immigrant background had lower self-reported emotional school engagement than native children with respect to classroom atmosphere and sense of belonging. They had less courage to talk about their thoughts in the class and felt lonely more than the children with a native background. In addition, children with an immigrant background more often reported that they had been bullies and seen bullying in the class. Children with an immigrant background had more emotional symptoms and peer problems reported by parents than children with a native background. Teachers did not report any significant differences in psychiatric symptoms between the two groups. The findings are discussed in detail below.

The results of this study regarding the lower emotional school engagement of children with an immigrant background with respect to classroom atmosphere and sense of belonging are consistent with previous studies on the school engagement of immigrant adolescents. A large review analyzing the emotional and the cognitive school engagement of immigrant adolescents in 41 countries [9], found that immigrant adolescents had weaker emotional school engagement but greater cognitive engagement than native adolescents. Adolescents with better teacher support or classroom climate often had a greater sense of belonging at school and had better attitudes towards school than other adolescents. In a recent OECD review [1], adolescents with immigrant background had a weaker sense of belonging at school. This was influenced by cultural and linguistic differences between the country of origin and the host country. The adolescent’s sense of belonging at school was inversely related to the linguistic distance between the language spoken at home and the language at school [1]. Both peer and teacher support has been shown to have a positive effect on school engagement in younger elementary school children, whereas later in school life, only teacher support is shown to have a positive effect on school engagement [41].

In this study, children with an immigrant background reported that they had more often been bullies and seen bullying in the class than native children. It is important to note that bully and victim roles remain relatively stable from childhood to adolescence [42]. The findings on the association of immigrant or ethnic status and bullying involvement in childhood and adolescence are inconsistent: According to a recent review of Xu et al. [43], some studies have found less bullying perpetration or victimization among immigrants and ethnic minorities, whereas some studies have reported more bullying perpetration or victimization, or stated that being an immigrant does not have an association with bullying involvement. The findings of this study are in line with previous studies showing that immigrant children and adolescents have reported participating in bullying [27, 44, 45]. No significant associations were found between bullying victimization and immigrant background in this study, while previous studies in the early educational [46], and primary school [47] settings in Finland have found more victimization among immigrant children. However, the findings of this study are in accordance with a study among Norwegian youth [44].

With regard to bullying perpetration, it has been proposed that the need for peer acceptance and affiliation is associated with bullying perpetration [44]. Moreover, acculturation stress experienced by immigrant adolescents has been related to physical aggression [48]. Aggression may thus be a response to acculturative stress [49]. However, neither parents nor teachers reported more aggression concerning conduct problems in children with an immigrant background in this study. Understanding the types of bullying perpetration might help to shed light on this finding. The bullying perpetrators can be divided followingly: (1) the aggressive bully is impulsive and aggressive to any person; (2) the anxious bully is insecure and friendless and uses aggression to deal with this stress; (3) the passive bully is aggressive in order to protect himself and to belong to the group [50]. Acculturation stress is suggested to be associated with passive or anxious bullying [51]. The types of bullying perpetration and their associations with the conduct problems may well explain the results showing that children with an immigrant background reported more bullying perpetration than natives, but parents and teachers did not report any differences in conduct disorders between the groups.

This study supports the migration morbidity perspective, with reference to the higher prevalence of emotional symptoms and peer problems reported by parents in children with an immigrant background. In addition, the finding regarding the teacher reports that found no differences in psychiatric symptoms between the groups is in concordance with some previous studies reporting that teachers do not report differences in psychiatric symptoms between native and immigrant children or report less emotional symptoms in immigrant children than parents [23, 52, 53]. The finding of this study correlates favorably with the results of Jäkel et al. [52] who found that when comparing immigrant mothers with German native mothers, Turkish immigrant mothers rated their children’s and adolescents’ total difficulties, emotional symptoms, peer problems and prosocial behavior significantly higher, while there were no differences in the teachers’ ratings between the two groups. In a Dutch study of Vollebergh et al. [23], immigrant parents reported higher internalizing, social and attention problem rates for their daughters than native parents, whereas teachers perceived lower levels of internalizing and social problems especially in immigrant boys, and higher levels of externalizing problems in both immigrant boys and girls. In a Dutch study of Crijnen et al. [53], teachers did not report any differences in mental health between Turkish immigrant and native children and adolescents, but curiously Turkish immigrant teachers reported higher total and internalizing problems for immigrant children and adolescents than the Dutch teachers did. A Finnish study of Säävälä [54] examined school welfare personnel’s and parents’ conceptions of the wellbeing of immigrant children and adolescents and found that they stressed different factors as risks and resources. In views of the school welfare personnel being immigrant in itself does not compose any substantial risk for wellbeing, whereas immigrant parents and native language teachers fear negative attitudes based on ethnic or racial group constitutes a substantial risk for immigrant children’s and adolescents’ wellbeing. Moreover, it has been argued that child health professionals’ identification of psychiatric problems is poorly associated with parent reports regarding economic immigrant children [55]. The findings described here seem to imply that teachers report less psychiatric symptoms than immigrant parents for immigrant children and adolescents, especially in regard of internalizing symptoms. It may be argued that teachers detect immigrant children’s and adolescents’ academic and adaptive problems more easily than their psychiatric problems [56]. Furthermore, one possible explanation for the difference in findings in parent and teacher reports considering emotional symptoms and peer problems could be that children with an immigrant background might actually exhibit problems more differently at home than at school compared to children with a native background.

Strengths and Limitations

This study adds to the limited body of the European literature of the school engagement and the psychiatric symptoms of children with an immigrant background in the first years of school. The multiple informants (child, parent, teacher) can be regarded as a strength of the study. That the children with an immigrant background formed a heterogeneous group with versatile backgrounds can be seen as a limitation. There are varying unknown reasons behind migration and the type and timing of parental or child’s personal migration and ethnic background all influence the child’s mental health outcome [18, 57]. Also the relatively low number of children with an immigrant background in the sample does not allow analyses in respect of ethnicity. Thus, this study is not comparable to studies focusing on specific immigrant groups. The use of a non-validated questionnaire to assess emotional school engagement can be regarded as a further limitation of the study.

Summary

The early school engagement and psychiatric symptoms in the first years of school are of great importance given their association to academic proficiency later in school life. This study explored emotional school engagement and psychiatric symptoms among 6–9-year-old children with an immigrant background in their first years of school compared to children with a Finnish native background. The results showed that children with an immigrant background in the first years of school had lower self-reported emotional school engagement and more psychiatric symptoms reported by parents when compared to natives. Teachers did not report any significant differences in psychiatric symptoms between the two groups. Overall, the findings imply that multiple assessment is to be recommended when identifying psychiatric symptoms of young children with an immigrant background. Moreover, these findings seem to highlight the need to establish school-based methods to support the school engagement and the mental health of children with an immigrant background in the first years of school.

References

OECD (2018) The resilience of students with an immigrant background. OECD, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264292093-en

Motti-Stefanidi F, Masten AS (2013) School success and school engagement of immigrant children and adolescents. Eur Psychol 18(2):126–135. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000139

Costello EJ, Maughan B (2015) Annual research review: optimal outcomes of child and adolescent mental illness. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56(3):324–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12371

Ladd GW, Buhs ES, Seid M (2000) Children’s initial sentiments about kindergarten: is school liking an antecedent of early classroom participation and achievement? Merrill-Palmer Q 40(2):255–279

Dimitrova R, Chasiotis A, van de Vijver F (2016) Adjustment outcomes of immigrant children and youth in Europe: a meta-analysis. Eur Psychol 21(2):150–162. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000246

Weiner IB, Easterbrooks MA, Lerner RM, Mistry J (2012) Handbook of psychology, developmental psychology. Wiley, Somerset

Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH (2004) School engagement. Rev Educ Res 74(1):59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

Lam S, Jimerson S, Wong BPH, Kikas E, Shin H, Veiga FH et al (2014) Understanding and measuring student engagement in school: the results of an international study from 12 countries. Sch Psychol Q 29(2):213–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000057

Chiu M, Pong S, Mori I, Chow B (2012) Immigrant students’ emotional and cognitive engagement at school: a multilevel analysis of students in 41 countries. J Youth Adolescence 41(11):1409–1425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9763-x

Fang L, Sun R, Yuen M (2016) Acculturation, economic stress, social relationships and school satisfaction among migrant children in urban China. J Happiness Stud 17(2):507–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9604-6

Blum RW, McNeely C, Nonnemaker J (2002) Vulnerability, risk, and protection. J Adolescent Health 31(1):28–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00411-1

Li Y, Lerner RM (2011) Trajectories of school engagement during adolescence. Dev Psychol 47(1):233–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021307

Whitlock JL (2006) Youth perceptions of life at school: contextual correlates of school connectedness in adolescence. Appl Dev Sci 10(1):13–29. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532480xads1001_2

Wang M, Eccles JS (2012) Social support matters: longitudinal effects of social support on three dimensions of school engagement from middle to high school. Child Dev 83(3):877–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01745.x

Janosz M, Archambault I, Morizot J, Pagani LS (2008) School engagement trajectories and their differential predictive relations to dropout. J Soc Issues 64(1):21–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00546.x

Motti-Stefanidi F, Masten A, Asendorpf JB (2015) School engagement trajectories of immigrant youth. Int J Behav Dev 39(1):32–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025414533428

Alonso-Fernández L, Alonso-Fernández N, Jiménez-García R, Hernández-Barrera V, Palacios-Ceña D (2017) Mental health and quality of life among Spanish-born and immigrant children in years 2006 and 2012. J Pediatr Nurs 36:103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2017.05.005

Belhadj Kouider E, Koglin U, Petermann F (2014) Emotional and behavioral problems in migrant children and adolescents in Europe: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 23(6):373–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0485-8

Atzaba-Poria N, Pike A, Barrett M (2004) Internalising and externalising problems in middle childhood: a study of Indian (ethnic minority) and English (ethnic majority) children living in Britain. Int J Behav Dev 28(5):449–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250444000171

Hölling H, Kurth B, Rothenberger A, Becker A, Schlack R (2008) Assessing psychopathological problems of children and adolescents from 3 to 17 years in a nationwide representative sample: results of the German health interview and examination survey for children and adolescents (KiGGS). Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 17(S1):34–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-008-1004-1

Vaage AB, Tingvold L, Hauff E, Ta TV, Wentzel-Larsen T, Clench-Aas J et al (2009) Better mental health in children of Vietnamese refugees compared with their Norwegian peers—a matter of cultural difference? Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 3:34. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-3-34

Stevens G, Pels TVM, Bengi-Arslan L, Verhulst FC, Vollebergh WAM, Crijnen AAM (2003) Parent, teacher and self-reported problem behavior in The Netherlands—comparing Moroccan immigrant with Dutch and with Turkish immigrant children and adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 38(10):576–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-003-0677-5

Vollebergh W, ten Have M, Dekovic M, Oosterwegel A, Pels T, Veenstra R et al (2005) Mental health in immigrant children in the Netherlands. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 40(6):489–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0906-1

Stevens G, Vollebergh WAM (2008) Mental health in migrant children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49(3):276–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01848.x

IOM (2017) World Migration Report 2018. UN, New York. https://doi.org/10.18356/f45862f3-en

Curtis P, Thompson J, Fairbrother H (2018) Migrant children within Europe: a systematic review of children’s perspectives on their health experiences. Public Health 158:71–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.01.038

Stevens G, Walsh SD, Huijts T, Maes M, Madsen KR, Cavallo F et al (2015) An internationally comparative study of immigration and adolescent emotional and behavioral problems: effects of generation and gender. J Adolesc Health 57:587–594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.07.001

Dimitrova R, Chasiotis A (2012) Are immigrant children in Italy better adjusted than mainstream Italian children? Contrib Hum Dev 24:35–47. https://doi.org/10.1159/000331024

von Grünigen R, Perren S, Nägele C, Alsaker FD (2010) Immigrant children’s peer acceptance and victimization in kindergarten: The role of local language competence. Br J Dev Psychol 28(3):679–697. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151009X470582

OECD (2017) Finding the way: a discussion of the Finnish migrant integration system. OECD Publishing, Paris

Statistics Finland (2018) Statistical yearbook of Finland 2018. Statistics Finland, Helsinki

Ladd GW, Dinella LM (2009) Continuity and change in early school engagement. J Educ Psychol 101(1):190–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013153

Kiviruusu O, Björklund K, Koskinen H, Liski A, Lindblom J, Kuoppamäki H et al (2016) Short-term effects of the “Together at School” intervention program on children’s socio-emotional skills: a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychol 4(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-016-0133-4

Ministry of Education and Culture, Finnish National Agency of Education (2018) Finnish Education in a nutshell. Available at https://www.oph.fi/en/statistics-and-publications/publications/finnish-education-nutshell Accessed 8 Dec 2019

Fredricks JA, McColskey W (2012) The measurement of student engagement: a comparative analysis of various methods and student self-report instruments. In: Christenson SL, Reschly AL, Wylie C (eds) Handbook of research on student engagement. Springer, Boston, pp 763–782

Finn JD (1989) Withdrawing from school. Rev Educ Res 59(2):117–142. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543059002117

Voelkl KE (1997) Identification with School. Am J Educ 105(3):294–318. https://doi.org/10.1086/444158

Goodman R (1997) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38(5):581–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Stone LL, Otten R, Engels RC, Vermulst AA, Janssens JM (2010) Psychometric properties of the parent and teacher versions of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire for 4-to 12-year-olds: a review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 13(3):254–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-010-0071-2

Borg A, Kaukonen P, Joukamaa M, Tamminen T (2014) Finnish norms for young children on the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Nord J Psychiatry 68(7):433–442. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2013.853833

Demir M, Leyendecker B (2018) School-related social support is associated with school engagement, self-competence and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in Turkish immigrant students. Front Educ 3:83. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00083

Zych I, Ttofi MM, Llorent VJ, Farrington DP, Ribeaud D, Eisner MP (2020) A longitudinal study on stability and transitions among bullying roles. Child Dev 91(2):527–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13195

Xu M, Macrynikola N, Waseem M, Miranda R (2020) Racial and ethnic differences in bullying: review and implications for intervention. Aggress Violent Behav 50:101340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.101340

Fandrem H, Strohmeier D, Roland E (2009) Bullying and victimization among native and immigrant adolescents in Norway. J Early Adolesc 29(6):898–923. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431609332935

Jansen PW, Mieloo CL, Dommisse-van Berkel A, Verlinden M, van der Ende J, Stevens G et al (2016) Bullying and victimization among young elementary school children : the role of child ethnicity and ethnic school composition. Race Soc Probl 8(4):271–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-016-9182-9

Kirves L, Sajaniemi N (2012) Bullying in early educational settings. Early Child Dev Care 182(3–4):383–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2011.646724

Strohmeier D, Kärnä A, Salmivalli C (2011) Intrapersonal and interpersonal risk factors for peer victimization in immigrant youth in Finland. Dev Psychol 47(1):248–258. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020785

Beiser M, Hamilton H, Rummens JA, Oxman-Martinez J, Ogilvie L, Humphrey C et al (2010) Predictors of emotional problems and physical aggression among children of Hong Kong Chinese, Mainland Chinese and Filipino immigrants to Canada. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 45(10):1011–1021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0140-3

Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, Prinzie P, Boelen PA, van der Schoot M, Telch MJ (2011) Prospective linkages between peer victimization and externalizing problems in children: a meta-analysis. Aggress Behav 37(3):215–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20374

Pearce J (1991) What can be done about the bully? In: Elliot M (ed) Bullying: a practical approach to coping for schools. Pearson Education Limited, Harlow, pp 70–89

Messinger AM, Nieri TA, Villar P, Luengo MA (2012) Acculturation stress and bullying among immigrant youths in Spain. J Sch Violence 11(4):306–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2012.706875

Jäkel J, Leyendecker B, Agache A (2015) Family and individual factors associated with turkish immigrant and german children’s and adolescents’ mental health. J Child Fam Stud 24(4):1097–1105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9918-3

Crijnen AAM, Bengi-Arslan L, Verhulst FC (2000) Teacher-reported problem behaviour in Turkish immigrant and Dutch children: a cross-cultural comparison. Acta Psychiatr Scand 102(6):439–444. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102006439.x

Säävälä M (2012) The burden of difference? School welfare personnel’s and parents’ views on wellbeing of migrant children in Finland. Finn Yearb Popul Res 47(47):31

Reijneveld SA, Harland P, Brugman E, Verhulst FC, Verloove-Vanhorick SP (2005) Psychosocial problems among immigrant and non-immigrant children Ethnicity plays a role in their occurrence and identification. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 14(3):145–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-005-0454-y

Margari L, Pinto F, Lafortezza ME, Lecce PA, Craig F, Grattagliano I et al (2013) Mental health in migrant schoolchildren in Italy: teacher-reported behavior and emotional problems. Neuropsych Dis Treat 9:231–241. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S37829

Silwal S, Lehti V, Chudal R, Suominen A, Lien L, Sourander A (2019) Parental immigration and offspring post-traumatic stress disorder: a nationwide population-based register study. J Affect Disord 249:294–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.02.002

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all participants and all research assistants involved.

Funding

Open access funding provided by National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL).. This work was supported by a grant from the Alli Paasikivi Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. The study protocol has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare in Helsinki, Finland (27.9.2012).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Parents provided informed consents for the participation of their children.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Parviainen, H., Santalahti, P. & Kiviruusu, O. Emotional School Engagement and Psychiatric Symptoms among 6–9-Year-old Children with an Immigrant Background in the First Years of School in Finland. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 52, 1071–1081 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-01086-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-01086-2