Abstract

Youth- and parent-rated screening measures derived from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) and Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA) were compared on their psychometric properties as predictors of caseness in adolescence (mean age 14). Successful screening was judged firstly against the likelihood of having an ICD-10 psychiatric diagnosis and secondly by the ability to discriminate between community (N = 252) and clinical (N = 86) samples (sample status). Both, SDQ and DAWBA measures adequately predicted the presence of an ICD-10 disorder as well as sample status. The hypothesis that there was an informant gradient was confirmed: youth self-reports were less discriminating than parent reports, whereas combined parent and youth reports were more discriminating—a finding replicated across a diversity of measures. When practical constraints only permit screening for caseness using either a parent or an adolescent informant, parents are the better source of information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Screening measures of child and adolescent mental health are widely used for predicting caseness, i.e. to identify individuals who are at high risk of having at least one psychiatric disorder or, more broadly, a high enough level of dimensionally measured psychopathology to warrant further assessment. Pediatricians and family practitioners screening for caseness can thereby assess which of their patients are most likely to benefit from referral to the restricted specialist child and adolescent mental health services [1]. Epidemiologists may choose to screen for caseness in multi-phase surveys, reserving more detailed assessments for those who screen positive, plus a random sample of those who screen negative. Researchers too may use screening measures as part of determining who meets inclusion or exclusion criteria for specific research projects.

Discrepancies between youth and adult information on mental health symptoms are one of the most robust findings in child and adolescent psychiatry. Informants often disagree about the presence or absence of symptoms, reflecting reporter bias, situation-specific behaviour, or random variation in measurement [2, 3]. These discrepancies are a major challenge for child and adolescent psychiatrists and psychologists and contribute to the difficulties detecting significant effects for therapy interventions. For diagnostic decision making, different algorithms have been suggested for combining parent and youth information [3, 4].

When the focus is on preschool and early school-aged children, the screening information is likely to be collected from parents as the cognitive function of children limits their ability to report on symptoms. While parent and teacher reports are of high validity for assessing children, the assessment of adult patients relies heavily on self-report, as shown in meta-analysis [5]. Adolescence (age 11–17) can be seen as a transitional phase where parent reports as well as adolescent reports generate relevant data. In this instance, the choice of informant is less obvious—for example, should clinicians screen 11–17 year olds by collecting information from parents, children or both? While there is empirical support for the notion that a wider range of informants generally provides more discriminating information across the lifespan [2, 6, 7] trying to use multiple informants may undermine the aim of generating a good enough answer rapidly and economically, and thereby reduce the use of evidence-based assessments in clinics [8].

Information about how the choice of informant influences screening properties potentially allows practitioners to make a better informed choice about the optimal trade-off for their particular purposes [4]. The present study investigated this issue by comparing several scales that have been derived from two widely used screening measures of mental health problems; the brief Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [9, 10] and the extensive Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA) [11].

When comparing the relative merit of various scores and categories for screening purposes, the greatest challenge is to decide how to judge merit. If there were a gold standard that was generally accepted as an accurate measure of caseness, it would be simple to judge different approaches to screening against this gold standard [12]. Unfortunately, there is no universally recognized standard. While clinicians are often confident about their own judgment, it is noteworthy that the correlation between different clinicians is generally poor, so they cannot all be right. Standardized diagnostic interviews are generally more reliable than clinicians [13, 14], but that does not rule out the possibility that they are reliably wrong. Arbitrarily adopting one specific diagnostic interview as the gold standard would be problematic, making it impossible, for instance, to investigate whether a brief questionnaire might be a better screening measure than a detailed diagnostic interview if it has already been decided a priori that detailed diagnostic interviews are the gold standard against which brief questionnaires should be judged.

In the long term, the relative merit of different screening approaches may be established through studies of prognosis, biomarkers or response to treatment [15]. In the meanwhile, an appealing approach is based on combining two plausible assumptions that take the place of a gold standard. The first assumption is that youths drawn from psychiatric clinics are more likely on average to have psychiatric disorders than youths drawn from community samples (accepting that this prediction is only probabilistic, with some youths in clinics not having disorders, and with some untreated youths in the community having disorders). The second assumption is that when experienced clinicians review detailed information from standardized diagnostic interviews, those youths rated by the clinicians as having at least one psychiatric disorder are, on average, more likely to have a disorder than youths who are rated as not having any psychiatric disorder. In the absence of a gold standard, convergence between the results based on these two different assumptions is particularly convincing.

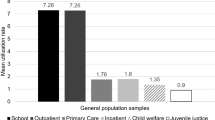

Previous investigations based on diagnostic interviews [16, 17] and rating scales [18–20] suggest that there is an informant gradient, with self-report information from youths (Y) having poorer screening properties than information from parents (P), and with the combination of youth and parent (PY) information providing the best screening properties (Y < P < PY). We hypothesized that this rank-ordering based on choice and combination of informants would hold across diverse approaches to screening, whether based on dimensions or categories; extensive or brief measures; or whether measures were based exclusively on symptoms, as opposed to including measures of impact that also consider how far these symptoms result in distress or social impairment (functional disability) for the young person. This hypothesis was tested by extracting various dimensional scales and categorical measures from the SDQ and the DAWBA which are outlined in the supplement table.

Method

Samples

The present study is based on samples from two different sites sharing a common language and much of their culture. The data was collected online from a community sample of N = 252 subjects from Mannheim, Germany and at clinical intake from a sample of N = 86 patients who attended the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Service of the Canton of Zurich, Switzerland. The Mannheim community sample is one arm of the IMAGEN sample described in more detail in [21]. Caucasian youths with diverse developmental backgrounds (socio economic status, cognitive and emotional development) were recruited from different high schools. The Zurich clinic sample is described in more detail in [22]. Family background characteristics such as socioeconomic status or information on parent respondents were not systematically assessed in the current study. For the present study only youths aged 11–17 years with full information on parent- and self-rated SDQ [9, 10] and DAWBA [11] were considered (N = 86). The mean age was 13.98 years (SD = 0.60 years, range 13–17 years) in the Mannheim community sample and 13.99 years (SD = 2.01 years, range 11–17 years) in the Zurich clinic sample (no significant difference; t = −0.04, df = 90. p = 0.970). As expected, the sex distribution was relatively even in the community sample (46.8 % male) and there was a significant male excess in the clinical sample (65.1 % male; χ2 = 8.59, df = 1, p = 0.003). The Zurich clinical study was approved by the local ethics committee of the Canton of Zürich and is registered as a randomized clinical trial (ISRCTN19935149). The Mannheim study was approved by the local ethics Committee of the University of Mannheim.

Measures

Subjects in both the community and clinical samples were assessed with the internet-based parent and youth versions of the SDQ [9, 10] and then DAWBA [11]. The SDQ is a questionnaire covering common mental health problem in children aged 2 to 17. The 20 items relating to emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity and peer problems can be summed to generate a total difficulty score ranging from 0 to 40. The SDQ has been shown to have dimensional as well as categorical qualities [23]. The SDQ is commonly administered with an impact supplement that asks whether the respondent thinks the youth has significant difficulties, and if so inquires about overall distress and social impairment—forming the basis for an impact score. In this study, the SDQ with impact supplement was administered to parents and to youths aged 11 or older.

The DAWBA [11] includes structured interview sections covering the major mental disorders, followed by a semi-structured part eliciting open-ended descriptions from respondents about areas of concern. Diagnostic predictions in line with ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria can be generated by computerized algorithms drawing on data from the structured questions, the DAWBA bands [24], and also by expert raters who review the answers of all informants to both structured and open-ended questions: these are what we subsequently refer to as expert diagnostic ratings. The DAWBA bands are based on an algorithm that combines the information from symptom and impact measures from all available respondents, e.g. parent report and adolescent report) It is not an average or an addition, but aims to follow the logic of the DSM and ICD classifications, e.g. giving more weight to symptoms of hyperactivity if reported across different situations and accompanied by impairment. The underlying logic and validation are reported in [25].

Since the DAWBA bands are quick, cheap and standardized [24], they have been used as the only source of diagnostic ratings in some research studies e.g. [26]. However, most researchers and clinicians using the DAWBA rely on specially trained clinical expert raters; after reviewing the open-ended text comments and the coherence of different respondents’ answers, roughly 20 % of all diagnoses proposed by the DAWBA bands are revised by expert raters in an investigator-based process [11, 27]. In this study, the expert diagnostic ratings form the basis for one of the two key tests of validity: how well does each possible measure predict that the individual has at least one ICD-10 psychiatric disorder? In analyses, the DAWBA bands are used as dimensional measures, and also dichotomized as categorical measures of caseness. The supplement table provides a summary of all dimensional scales and dichotomous measures derived from the SDQ and DAWBA that have been used in the present study.

Statistical Analyses

For the five dimensional SDQ and DAWBA scales (see supplement table), the analyses compared the area under the curves (AUC) based on receiver operating characteristics (ROC) [28]. AUCs as a measure of excellence for predicting diagnosis should be interpreted as follows: poor (50–.70); moderate to fair (.70–.80); good (.80–.90), and excellent (.90–1.00) [28]. A critical z-ratio was calculated using a formula correcting for the non-independence of the scales [29].

For the eight dichotomous SDQ and DAWBA measures, the analyses present sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, efficiencies, and kappa coefficients. According to Landis and Koch, kappa coefficients between 0.21 and 0.4 indicate a fair agreement, between 0.41 and 0.6 a moderate agreement, and between 0.61 and 0.8 a substantial agreement [30]. In addition, differences between kappa coefficients were tested for significance by z-tests following the procedure described by Donner et al. and corrected for the missing square root in the denominator of the z-formula in the article [31].

Results

Among the 252 adolescents (118 males and 134 females) in the Mannheim community sample, 21 (8.3 %) received a DAWBA expert diagnostic rating (i.e. at least one ICD-10 diagnosis); 6 (2.4 %) had internalizing disorders (e.g. separation anxiety disorders, specific phobias, social phobias, generalized anxiety disorders, other anxiety disorders, posttraumatic stress disorders, obsessive compulsive disorders, depression, other affective disorders), 14 (5.6 %) had externalizing disorders (e.g. hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder), and 2 (0.8 %) had other disorders (e.g. autism, selective mutism, tic disorders, eating disorders). One patient showed co-morbid internalizing and externalizing disorders. Among the 86 adolescents (56 males and 30 females) in the Zurich clinic sample, 62 subjects (72.1 %) received a DAWBA expert diagnostic rating with 38 subjects (44.2 %) having internalizing disorders, 26 (30.2 %) externalizing disorders and 8 (9.3 %) other disorders. There were several co-morbid cases, see [22]. A total of 24 subjects (27.9 %) did not reach the threshold for any psychiatric disorder. As expected, the likelihood of having at least one psychiatric disorder differed significantly between the two samples, with a higher proportion of diagnoses in the clinic sample (χ2 = 140.70, df = 1, p < 0.001).

Table 1 shows findings from the ROC analyses for the prediction of sample status and expert diagnostic rating for the five dimensional scores. The AUC values were above 0.8-except for the two youth scores predicting sample status which fell slightly below- and may thus be regarded as very good [28]. When comparing the various scores by critical z-ratios, 6 of the 8 comparisons supported the informant gradient and the other 2 comparisons were non-significant: the Parent-SDQ outperformed the Youth-SDQ for predicting sample status (AUC 0.912 vs. 0.749, z = 5.304, p < 0.001) and for predicting expert ratings of any ICD-10 disorder (AUC 0.879 vs. 0.809, z = 2.383 p = 0.009); the Parent-DAWBA band outperformed the Youth-DAWBA band for predicting sample status (AUC 0.838 vs. 0.707, z = 3.512, p < 0.001) but not for predicting expert ratings of any ICD-10 disorder (AUC 0.859 vs. 0.823, z = 0.963, p = 0.168.); the Parent-Youth-DAWBA band was not more accurate than the Parent-DAWBA band for predicting sample status (AUC 0.822 vs. 0.838, z = −0.870, p = 0.192) but was more accurate for predicting expert ratings of any ICD-10 disorder (AUC 0.909 vs. 0.859, z = 2.469, p = 0.007); and the Parent-Youth-DAWBA band was more accurate than the Youth-DAWBA band for predicting both sample status (AUC 0.822 vs. 0.707, z = 4.326, p < 0.001) and expert ratings of any ICD-10 disorder (AUC 0.909 vs. 0.823, z = 3.442, p < 0.001).

The predictions based on the eight dichotomous predictors to sample status are shown in Table 2. Whereas specificity was highly satisfactory for all eight predictors, it is noteworthy that sensitivity was poorer for Youth-based measures.

The informant gradient was supported by all 4 comparisons by critical z-ratios : high Parent-SDQ score outperformed high Youth-SDQ score (z = 4.95, p < 0.001); high Parent-SDQ symptom + impact outperformed high Youth-SDQ symptom + impact (z = 5.36, p < 0.001); high Parent-DAWBA band outperformed high Youth-DAWBA band (z = 2.25, p = 0.012); and high Parent-Youth-DAWBA band outperformed high Parent-DAWBA band (z = 2.34, p = 0.010).

The Table 3 shows the predictions based on the same eight dichotomous predictors to expert diagnostic ratings in the combined community and clinical samples. Mirroring the findings described in the previous paragraph, all 4 comparisons by critical z-ratios again supported the informant gradient: high Parent-SDQ score outperformed high Youth-SDQ score (z = 4.39, p < 0.001); high Parent-SDQ symptom + impact outperformed high Youth-SDQ symptom + impact (z = 4.71, p < 0.001); high Parent-DAWBA band outperformed high Youth-DAWBA band (z = 2.25, p = 0.012); and high Parent-Youth-DAWBA band outperformed high Parent -DAWBA band (z = 2.96, p = 0.002).

Visual inspection of Tables 3 and 4 shows that the general pattern of results is similar whether screening properties are judged from analyses of sample status (Table 2) or clinical expert ratings (Table 3). This was evaluated statistically by a consistency analysis for single measures; the intraclass correlation was 0.85 (95% CI 0.41–0.97), p = 0.001.

Though the rank-ordering of the kappa coefficients was generally similar whether judged by sample status or clinical rating, there were some significant differences as shown in Table 4. For DAWBA bands, but not for SDQ-derived measures, the kappa coefficients were significantly lower (by an average of 0.15) when judged by clinical status rather than by expert rating.

Discussion

This study assessed the screening properties of SDQ and DAWBA dimensional scales and dichotomous measures in both a clinical and a community sample. As expected the two samples differed significantly in the frequency of psychiatric diagnoses. The study has confirmed and extended previous findings on an information gradient relevant to the assessment of adolescents (11–17 years): self-reports are less predictive of caseness than are parent reports; while the combination of parent and self-reports generally does best. This superiority is in keeping with conclusions from previous studies [16, 17, 20, 32, 33] that combining parent and youth reports improves the detection of adolescent psychopathology. When, for financial or other practical reasons, only the parent or the adolescent can be assessed in order to predict caseness, then our findings suggest that parents will generally be the informants of choice. For screening purposes, studies or services with constrained resources may restrict themselves to just parent reports for screening purposes—the present study suggests that the loss of discriminative power that results from not collecting youth self-report is moderate rather than massive.

The current study has extended previous findings by demonstrating that an information gradient is apparent across a wide variety of screening approaches, whether dimensional or categorical; respondent or investigator based, whether based on a brief questionnaire or on a much more extensive assessment; and whether conducted with or without consideration of impact (i.e. distress and social incapacity) as measured in a psychometrically sound way [10, 34]. It is worth noting, however, that this study may have underestimated the benefits of obtaining adolescent self-report because it focused on the prediction of caseness (i.e. any psychiatric disorder) in younger teenagers. It is plausible that the incremental information of self-report may be more evident for older teenagers as in the study by Smith [35] There are good reasons to integrate discrepant diagnostic information according to rules of evidence and not solely based on statistical test or computerized algorithms, as shown in the study of Jensen et al [6]. The DAWBA expert diagnostic process may be seen as an attempt to integrate discrepant information beyond computerized algorithms. Further studies are needed to show which informant serves best for which age group and disorder, as judged by outcome studies or biomarkers [36]. While there is broad agreement that there are benefits in obtaining parent and/or teacher information in the assessment of child psychopathology [37, 38], the assessment of adult psychopathology relies mostly on self-reports even though Achenbach showed that cross-informant data is relevant across the life span [5]. The results of the current study support the use of supplementing adolescent self report – the effect is sufficiently marked and consistent that it would be surprising if cross-informant data did not add to predictive power at least for younger adults, and perhaps more generally.

As discussed in the introduction, our comparison of the screening properties of information obtained from different informants (or combinations of informants) would ideally have based on validation against gold standard assessments; but in the absence of a universally accepted gold standard, we used instead two sets of assumptions that will be plausible to a wide range of child mental health specialists: firstly, that caseness is more likely in clinical than community samples (validation by prediction of sample status), and secondly that caseness is more likely in children assigned diagnoses on the basis of standardized psychiatric assessments, including open-ended descriptions of symptoms (validation by prediction of clinical diagnosis). It is worth emphasizing that these are predictions about what will be true on average in large samples – not about what is indisputably true in any one instance. We chose to use both sample status and clinical diagnosis because they have complementary advantages and limitations: clinical diagnosis is generally more persuasive for clinicians, but potentially introduces some circularity since the expert diagnostic rating draws on both the SDQ and DAWBA bands; By contrast, sample status has the advantage of being independent of both SDQ and DAWBA bands. Our analyses based on these two approaches to validation led to similar conclusions, as is apparent from a comparison of Tables 2 and 3, and from a substantial intraclass correlation coefficient. This convergence can be seen as an internal replication that strengthens the evidence for our findings.

This study of screening is focused on predicting caseness rather than predicting the type of disorder. We did not have the sample size needed to examine the extent to which parent and youth reports contribute differently to the more specific prediction of the type of disorder, e.g. internalizing or externalizing – a significant limitation given the evidence for significant variation in parent-child concordance by type of disorder [25, 32, 39–41].

In conclusion, studies or services with constrained resources may sometimes choose to restrict themselves to just parent reports for screening purposes—the present study suggests that the loss of discriminative power that results from not collecting youth self-report is moderate rather than massive.

Summary

This study compared the predictive validity of thirteen different screening scales and measures derived from two different instruments: the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) and Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA) in a combined sample of young teenagers recruited from a community sample (N = 252) or a clinic sample (N = 86). We tested the hypothesis that in the prediction of caseness, there is an informant gradient with self reports from youths less suited than parent reports; and with parent reports less suited than the combination of parent and youth reports. Using Receiver Operation Characteristic (ROC) analyses and kappa statistics, both, SDQ and DAWBA measures were successfully predicting the presence of an ICD-10 disorder as well as clinic sample status. Kappa statistics confirmed the hypothesis that there was an informant gradient: youth self-reports were less useful than parent reports for predicting diagnosis, whereas combined parent and youth reports were more discriminating—a finding replicated across a diversity of SDQ and DAWBA scales and measures.

For clinical and research purposes, parent and youth information should be considered whenever possible to assess psychiatric illness in young teenagers, but when practical considerations mean that only one informant can be used in screening for caseness, that informant should generally be the parent.

References

Costello EJ, Egger H, Angold A (2005) 10-year research update review: the epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44:972–986

De Los Reyes A, Kazdin A (2005) Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: a critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychol Bull 131:183–509

De Los Reyes A, Thomas SA, Goodman KL, Kundey SMA (2013) Principles underlying the use of multiple informants’ reports. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 9:123–149

Piacentini JC, Cohen P, Cohen J (1992) Combining discrepant diagnostic information from multiple sources: are complex algorithms better than simple ones? J Abnorm Child Psychol 20:51–63

Achenbach TM, Krukowski RA, Dumenci L, Ivanova MY (2005) Assessment of adult psychopathology: meta-analyses and implications of cross-informant correlations. Psychol Bull 131:361–382

Jensen PS, Rubio-Stipec M, Canino G, Bird HR, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME et al (1999) Parent and child contributions to diagnosis of mental disorder: are both informants always necessary? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38:1569–1579

Ramirez Basco M, Bostic JQ, Davies D, Rush AJ, Witte B, Hendrickse W et al (2000) Methods to improve diagnostic accuracy in a community mental health setting. Am J Psychiatry 157:1599–1605

Jensen-Doss A, Hawley KM (2010) Understanding barriers to evidence-based assessment: clinician attitudes toward standardized assessment tools. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 39:885–896

Goodman R (1997) The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38:581–586

Goodman R (1999) The extended version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 40:791–799

Goodman R, Ford T, Richards H, Gatward R, Meltzer H (2000) The Development and Well-Being Assessment: description and initial validation of an integrated assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 41:645–655

Kraemer HC, Measelle JR, Ablow JC, Essex MJ, Boyce WT, Kupfer DJ (2003) A new approach to integrating data from multiple informants in psychiatric assessment and research: mixing and matching contexts and perspectives. Am J Psychiatry 160:1566–1577

Jensen AL, Weisz JR (2002) Assessing match and mismatch between practitioner-generated and standardized interview-generated diagnoses for clinic-referred children and adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol 70:158–168

Rettew DC, Lynch AD, Achenbach TM, Dumenci L, Ivanova MY (2009) Meta-analyses of agreement between diagnoses made from clinical evaluations and standardized diagnostic interviews. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 18:169–184

Jensen-Doss A, Weisz JR (2008) Diagnostic agreement predicts treatment process and outcomes in youth mental health clinics. J Consult Clin Psychol 76:711–722

Jensen P, Roper M, Fisher P, Piacentini J, Canino G, Richters J et al (1995) Test-retest reliability of the diagnostic interview schedule for children (DISC 2.1). Parent, child, and combined algorithms. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52:61–71

Schwab-Stone ME, Shaffer D, Dulcan MK, Jensen PS, Fisher P, Bird HR et al (1996) Criterion validity of the NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version 2.3 (DISC-2.3). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 35:878–888

Becker A, Hagenberg N, Roessner V, Woerner W, Rothenberger A (2004) Evaluation of the self-reported SDQ in a clinical setting: do self-reports tell us more than ratings by adult informants? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 13(Suppl 2):II17–II24

Gizer IR, Waldman ID, Abramowitz A, Barr CL, Feng Y, Wigg KG et al (2008) Relations between multi-informant assessments of ADHD symptoms, DAT1, and DRD4. J Abnorm Psychol 117:869–880

van Dulmen MHM, Egeland B (2011) Analyzing multiple informant data on child and adolescent behavior problems: predictive validity and comparison of aggregation procedures. Int J Behav Dev 35:84–92

Schumann G, Loth E, Banaschewski T, Barbot A, Barker G, Buchel C et al (2010) The IMAGEN study: reinforcement-related behaviour in normal brain function and psychopathology. Mol Psychiatry 15:1128–1139

Aebi M, Kuhn C, Metzke CW, Stringaris A, Goodman R, Steinhausen HC (2012) The use of the development and well-being assessment (DAWBA) in clinical practice: a randomized trial. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 21:559–567

Goodman A, Goodman R (2009) Strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a dimensional measure of child mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48:400–403

Goodman A, Heiervang E, Collishaw S, Goodman R (2011) The ‘DAWBA bands’ as an ordered-categorical measure of child mental health: description and validation in British and Norwegian samples. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46:521–532

Goodman R, Renfrew D, Mullick M (2000) Predicting type of psychiatric disorder from Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) scores in child mental health clinics in London and Dhaka. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 9:129–134

Viner RM, Booy R, Johnson H, Edmunds WJ, Hudson L, Bedford H et al (2012) Outcomes of invasive meningococcal serogroup B disease in children and adolescents (MOSAIC): a case-control study. Lancet Neurol 11:774–783

Foreman D, Morton S, Ford T (2009) Exploring the clinical utility of the Development And Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA) in the detection of hyperkinetic disorders and associated diagnoses in clinical practice. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50:460–470

Hsiao JK, Bartko JJ, Potter WZ (1989) Diagnosing diagnoses. Receiver operating characteristic methods and psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry 46:664–667

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ (1983) A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology 148:839–843

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33:159–174

Donner A, Shoukri MM, Klar N, Bartfay E (2000) Testing the equality of two dependent kappa statistics. Stat Med 19:373–387

Cantwell DP, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR (1997) Correspondence between adolescent report and parent report of psychiatric diagnostic data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:610–619

De Los Reyes A, Augenstein TM, Wang M, Thomas SA, Drabick DA, Burgers DE et al (2015) The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychol Bull 141:858–900

Stringaris A, Goodman R (2013) The value of measuring impact alongside symptoms in children and adolescents: a longitudinal assessment in a community sample. J Abnorm Child Psychol 41:1109–1120

Smith SR (2007) Making sense of multiple informants in child and adolescent psychopathology: a guide for clinicians. J Psychoeduc Assess 25:139–149

Stoyanov D, Machamer P, Schaffner KF (2013) In quest for scientific psychiatry: toward bridging the explanatory gap. Philos Psychiatr Psychol 20:261–273

Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT (1987) Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychol Bull 101:213–232

Johnson S, Hollis C, Marlow N, Simms V, Wolke D (2014) Screening for childhood mental health disorders using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: the validity of multi-informant reports. Dev Med Child Neurol 56:453–459

De Los Reyes A, Bunnell BE, Beidel DC (2013) Informant discrepancies in adult social anxiety disorder assessments: links with contextual variations in observed behavior. J Abnorm Psychol 122:376–386

Ford T, Last A, Henley W, Norman S, Guglani S, Kelesidi K et al (2013) Can standardized diagnostic assessment be a useful adjunct to clinical assessment in child mental health services? A randomized controlled trial of disclosure of the Development and well-being assessment to practitioners. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 48:583–593

Goodman R, Ford T, Simmons H, Gatward R, Meltzer H (2003) Using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) to screen for child psychiatric disorders in a community sample. Int Rev Psychiatry 15:166–172

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Goodman is owner of Youthinmind Ltd, which produces no-cost and low-cost websites related to the SDQ and DAWBA. Dr. Banaschewski served in an advisory or consultancy role for Hexal Pharma, Lilly, Medice, Novartis, Otsuka, Oxford outcomes, PCM scientific, Shire and Viforpharma. He received conference attendance support and conference support or received speaker’s fee by Lilly, Medice, Novartis and Shire. He is/has been involved in clinical trials conducted by Lilly, Shire and Viforpharma. The present work is unrelated to the above grants and relationships. During the last 3 years, Dr. Steinhausen served in an advisory or consultancy role or as speaker for Medice and Shire. The present work is unrelated to the above grant and relationships. All other authors report no conflict of interests with the present study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuhn, C., Aebi, M., Jakobsen, H. et al. Effective Mental Health Screening in Adolescents: Should We Collect Data from Youth, Parents or Both?. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 48, 385–392 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0665-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0665-0