Abstract

Alzheimer disease (AD) is the most common progressive neurodegenerative disorder. AD causes enormous personal and economic burden to society as currently only limited palliative therapeutic options are available. The pathological hallmarks of the disease are extracellular plaques, composed of fibrillar amyloid-β (Aβ), and neurofibrillary tangles inside neurons, composed of Tau protein. Until recently, the search for AD therapeutics was focussed more on the Aβ peptide and its pathology, but the results were unsatisfying. As an alternative, Tau might be a promising therapeutic target as its pathology is closely correlated to clinical symptoms. In addition, pathological Tau aggregation occurs in a large group of diseases, called Tauopathies, and in most of them Aβ aggregation does not play a role in disease pathogenesis. The formation of Tau aggregates is triggered by two hexapeptide motifs within Tau; PHF6* and PHF6. Both fragments are interesting targets for the development of Tau aggregation inhibitors (TAI). Peptides represent a unique class of pharmaceutical compounds and are reasonable alternatives to chemical substances or antibodies. They are attributed with high biological activity, valuable specificity and low toxicity, and often are developed as drug candidates to interrupt protein–protein interactions. The preparation of peptides is simple, controllable and the peptides can be easily modified. However, their application may also have disadvantages. Currently, a few peptide compounds acting as TAI are described in the literature, most of them developed by structure-based design or phage display. Here, we review the current state of research in this promising field of AD therapy development.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Tauopathies are a variety of progressive neurodegenerative disorders, characterized by the deposition of the abnormally aggregated microtubule-associated protein Tau. They include about 20 diseases, e.g. Huntington disease (HD), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), argyrophilic grain disease (AGD), primary age-related tauopathy (PART), chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), and, most abundant, Alzheimer disease (AD) (Arendt et al. 2016).

Today, over 55 million people live with dementia worldwide, with forecasts reaching 78 million by 2030, and dementia is now the 7th leading cause of mortality globally (World Alzheimer Report 2021). AD is the most common cause for dementia, accounting for almost 70% of cases, and clinically characterized by memory loss, apathy and depression, impaired judgement, confusion, disorientation and other symptoms. Ageing is the main risk factor for AD. As there are only limited palliative therapeutic options for AD, the disease causes enormous personal and economic burden to society.

The pathological hallmarks of AD are extracellular plaques, composed of fibrillar amyloid-β (Aβ), and neurofibrillary tangles inside of neurons, composed of Tau, as already described by Alois Alzheimer in 1907 (Alzheimer et al. 1995).

Tau is a highly soluble and natively unfolded protein, mainly expressed in neurons, which is involved in the stabilization and organization of microtubules. Resulting from alternative splicing of 16 exons of the microtubule-associated protein Tau (MAPT) gene, located on chromosome 17q21, six isoforms are generated in the central nervous system (CNS). These can be divided into 4R Tau, containing 4 repeats (31–32 amino acids each), and 3R Tau, containing three repeats (lacking repeat 2; R2) (Wang and Mandelkow 2016).

The physiological functions of Tau are regulated by a variety of post-translational modifications, e.g. phosphorylation, glycation, acetylation, etc. In particular, the hyperphosphorylation of Tau is associated with its detachment from microtubules and pathological Tau aggregation (Morris et al. 2011).

Recent data have demonstrated that not only deposited fibrils (tangles) have toxic effects, but also that small, soluble protein oligomers play a fundamental role in AD pathology, as they cause synaptic and mitochondrial dysfunction. They might cause neurodegeneration a long time before protein fibrilization and deposition starts (Lasagna-Reeves et al. 2011; Kumar et al. 2014).

It has been shown that Tau assembly into paired helical filaments (PHFs) is strongly driven by two hexapeptide fragments within Tau: PHF6* (275-VQIINK-280) and PHF6 (306-VQIVYK-311). The PHF6 sequence is located at the beginning of the third repeat (R3) and can be found in all Tau isoforms. In contrast, the PHF6* sequence is placed at the beginning of the second repeat (R2) and is only present in four-repeat (4R) Tau isoforms. Both hexapeptide motifs show the highest predicted β-structure potential within the Tau sequence, and point mutations in the hexapeptide regions can change β-propensity, leading to an increase or decrease of aggregation (von Bergen et al. 2000, 2001; Barghorn et al. 2004).

The amyloid hypothesis states that in the progression of AD pathology, Aβ plaques appear first, leading to Tau hyperphosphorylation, tangle formation and neurodegeneration (Selkoe and Hardy 2016). However, the relationship and interplay of Aβ and Tau is still poorly understood. Recent data suggest that Tau pathology is not simply a downstream process of Aβ aggregation (Nisbet et al. 2015; Pourhamzeh et al. 2021).

Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging studies reveal that amyloid accumulation may predict the onset of Tau accumulation. However, Tau accumulation only predicts the onset of cognitive impairment, while the onset of Tau pathology occurs at the same time as the symptoms appear (Roe et al. 2013; Johnson et al. 2016; Hanseeuw et al. 2019). Pathological Tau aggregation, having a detrimental effect on neuronal function in preclinical models (Iqbal et al. 2005), spreads to various brain areas in a stereotypical pattern, correlating tightly with disease severity (Braak and Braak 1991). It has been demonstrated that Tau pathology spreads by intraneuronal transfer, a phenomenon denoted as “Tau pathology propagation”, in a prion-like way (Guo and Lee 2011; Holmes and Diamond 2014).

For these reasons, amongst others, Tau has come increasingly into focus for AD therapeutics research as an alternative or complement to Aβ-targeted therapeutic approaches (Lovestone and Manji 2020; Soeda and Takashima 2020). Several potential therapeutic substances targeting Aβ pathology, such as Aβ antibodies, secretase inhibitors or Aβ aggregation inhibitors, have failed in clinical trials due to numerous reasons. This however is similar to essentially all advanced clinical trials on AD (Cummings et al. 2018). Only the Aβ oligomer-targeting antibody Aducanumab has recently obtained a tentative FDA approval. However, this decision is still highly controversial, and the efficacy of Aducanumab has still to be proven in future clinical studies (Knopman et al. 2021; Mullard 2021; Walsh et al. 2021).

In order to reduce Tau pathology in AD, a variety of small molecules, including modulators of post-translational modifications and aggregation inhibitors of Tau, have been described. Most of them are in the preclinical stage (Bulic et al. 2013). Fourteen molecules have already entered clinical phases, but only the compound LMTM, a derivative of methylene blue, is currently under clinical investigation in phase III (Wang et al. 2021). According to the Alzforum webpage, earlier clinical trials with methylene blue derivatives failed (https://www.alzforum.org/therapeutics/lmtm).

Peptides, composed of two or more (up to 100) amino acids, represent a unique class of pharmaceutical compounds and are reasonable alternatives to chemical substances. Physiologically, they act as key regulators of biological functions and are attributed with high biological activity, valuable specificity, and in most cases, low toxicity (Lien and Lowman 2003; Danho et al. 2009). The preparation of peptides is simple, controllable and the peptides can be easily modified (Liu et al. 2016). They are often developed as drug candidates to interrupt protein–protein interactions. Currently, more than 400 peptide drugs are under clinical investigation, 60 are already approved in the USA, Europe or Japan (Lee et al. 2019).

Peptide drugs might also have disadvantages such as biological instability and membrane and blood–brain barrier impermeability (Henninot et al. 2018), but at least some peptides were demonstrated to cross cell membranes or/and the blood–brain barrier (Pappenheimer et al. 1997; Funke et al. 2010; Dammers et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2020; Malhis et al. 2021; Aillaud et al. 2022). The problem of in vivo instability due to proteases can be overcome by chemical modification or the usage of D-amino acid peptides (Liu et al. 2010; Leithold et al. 2016; Lee et al. 2019). D-amino acid peptides have already been shown to be protease resistant and less immunogenic than the respective L-peptides (Schumacher et al. 1996; Chalifour et al. 2003; Sadowski et al. 2004).

Currently, a few peptide compounds developed as TAI have been described in the literature. All of them are still in preclinical stages, but one compound has already been successfully tested in AD mouse models. Here, we review the current state of research in this interesting and promising field of AD therapy development. The main results of current studies are summarized in Table 1. See Fig. 1 as a summary on (D)-Peptide generation for application as TAI.

(D)-Peptide generation for application as Tau aggregation inhibitors (TAI). A Methods for identification of TAI peptides. (1) Phage display procedure. Target molecule immobilized on solid phase is incubated with a phage display library. Specific library phages bind to the target molecule and unbound phages are removed by washing. Bound library phages are eluted and then amplified in E. coli. Finally, the amplified phages are used in the next biopanning round. After serval rounds, phage DNA can be analyzed to obtain therapeutic peptides. (2) Principle of mirror image phage display. Target molecule is used as D-enantiomer in the selection process. Biopanning is performed with phages presenting L-peptides. Finally, the D-enantiomeric form of the selected L-peptide is synthesized. (3) Another method of peptide identification offers in silico modelling using a variety of software. B Binding sites of established peptides summarized in this article

Methods: Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We have scanned novel publications listed on PubMed weekly since 2010 using the search terms “Alzheimer disease” and “Tau”. In addition, we performed searches using the terms “Tau”, aggregation inhibitors” and “peptides” and have analysed review articles on Tau aggregation inhibitors in general. All publications we have found reporting on peptides as Tau aggregation inhibitors to develop therapeutics for AD were included in this review article.

Literature Overview

Peptides Selected by Structure-Based Rational Design

The first study on Tau aggregation inhibiting peptides developed by computer-aided, structure-based design was published in 2011 by the group of David Eisenberg. The authors used a known crystal structure of the dual β-sheet “steric zipper” Tau segment VQIVYK (PHF6 sequence, located in R3 of Tau) as a template to design peptide aggregation inhibitors (Sievers et al. 2011). The “Rosetta” software (Kuhlman et al. 2003) was used to find non-natural peptides to target and block the ends of the PHF6 fibrils.

A tight interface was designed between the peptide and the fibril end to hinder addition of new building blocks. Four D-amino acid peptides were found, of which one, D-tlkivw, inhibited fibril formation of the PHF6-segment, but also of K12 and K19, two Tau constructs which lack the repeat R2 (Friedhoff et al. 1998), as shown by Thioflavin S (ThS) assays and electron microscopy (EM). Scrambled versions and the diastereomer, L-TLKIVW, were significantly less effective in inhibition of fibril formation. The position of the D-amino acid inhibitor at the end of fibrils of Tau K19 could be visualized using EM. Evaluation of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy data suggested a binding of D-tlkivw to PHF6 fibrils with an apparent dissociation constant of 2 µM, while the D-peptide seemed not to interact with monomers (Sievers et al. 2011).

However, whether the D-peptide inhibits full-length Tau (TauFL) aggregation was not demonstrated in this article, as only shortened K12 and K19 Tau constructs missing R2 with enhanced aggregation propensity were used. Therefore, the very similar PHF6* sequence is missing in both constructs. Later, the group reported that D-tlkivw was not able to inhibit TauFL aggregation, suggesting that TAI compounds based on the PHF6 sequence might be less effective in aggregation inhibition of TauFL (Seidler et al. 2018).

In 2018, the same group reported on structures of fibrils of a VQIINK (PHF6*) containing segment, forming steric zippers, as determined by the cryo EM method micro electron diffraction (MicroED) (Seidler et al. 2018). Those structures were the starting point for the design of PHF6* inhibitor peptides that block TauFL aggregation and seeding. Bulky amino acid sidechains were modelled into the structure and amino acids were identified that could interfere with the two possible interfaces observed.

Two inhibitors derived from the PHF6* sequence, MINK and WINK, were found to inhibit TauFL fibril formation in Thioflavin T (ThT) assays. However, while WINK showed no detectable self-aggregation, MINK was found to self-aggregate to a certain extent. Both inhibitors could reduce the ability of exogenous TauFL fibrils to seed intracellular Tau in HEK293 biosensor cells expressing Tau-K18-(P301S)-EYFP in a dose-dependent way, whereas the VQIVYK (PHF6) targeted inhibitor D-tlkivw inhibited seeding poorly (IC50 value of 52.2 µM, compared to 22.6 and 28.9 µM for MINK and WINK, respectively).

A variety of possible phase 2 inhibitors were designed on the basis of a second structural polymorph of PHF6* amyloid fibrils, revealing another possible interface. MINK was redesigned to incorporate another steric clash to disrupt the third interface. The most effective inhibitor peptide, W-MINK, blocked TauFL fibril seeding even more successfully than MINK, with IC50 = 1.1 µM. Together, the results indicate that VQIINK (PHF6*) is, in comparison to PHF6, a superior target for TAI (Seidler et al. 2018). In this study, however, only one single PHF6 targeting peptide, developed in their own group, D-tlkivw, was used for comparison.

In 2019, the group of Eisenberg reported evidence supporting the hypothesis that Aβ-induced cross-seeding of Tau could promote tangle formation in AD. The idea was then to find peptide inhibitors able to prevent Aβ aggregation and to block the binding site of Aβ with Tau (Griner et al. 2019), presumably PHF6 and PHF6*, as already hypothesized (Guo et al. 2006; Miller et al. 2011). The authors used microED to determine the atomic structure of an Aβ steric zipper fibril-like fragment, Aβ16-26, containing the hereditary mutation D23N.

A Rosetta-based strategy was used to design capping peptide inhibitors on a search model of Aβ16-22. After the first round of design, four L-peptides and two D-peptides were selected for further characterization. None of the inhibitors was toxic to cells as shown in MTT-tests (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-didiphenyltetrazolium bromide), but only one inhibitor, designated D1, eliminated toxic effects of Aβ1-42 on Neuro-2a (N2a) cells at a 10 molar excess.

In a second round of design, six new inhibitors, designated D1a-D1f, were selected and tested. Two of them, D1b and D1d, reduced Aβ1-42 toxicity on N2a cells efficiently in a tenfold excess and equimolar ratio. D1, D1b and D1d elicited a dose-dependent response, and the IC50 value was estimated to be less than 1 µM. D1b and D1d were more effective than D1 in reducing fibril formation. The L-amino acid form of D1 did not reduce cell toxicity, as judged by MTT assay. The reduction of Aβ toxicity could be explained by a dose-dependent inhibition of Aβ aggregation, as demonstrated by ThT assays and transmission electron microscope (TEM) analysis. Antibody studies indicated that the inhibitors reduced Aβ oligomers as well as Aβ fibrils. In addition, the reduction of pre-formed Aβ aggregate toxicity by inhibitors D1b and D1d could be demonstrated with D1d being more effective, and there was evidence that pre-formed fibrils were either capped or coated.

Next, the authors could show that Aβ aggregates were able to seed Tau aggregation in Tau biosensor cells expressing Tau-K18 (P301S) EYFP, suggesting that there is an interaction between Tau and Aβ in the microtubule-binding domain. The inhibitor peptides were able to reduce seeding of Tau by aggregated Aβ, D1b being most effective. In addition, D1, D1b and D1d were able to reduce aggregation of Tau monomers, as demonstrated by ThT assays. They were not general amyloid inhibitors, as aggregation of human islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) and α-Synuclein was not inhibited. The inhibitors also prevented TauFL fibril seeding in Tau biosensor cells, D1b being the most effective inhibitor (IC50 value of 4.5 µM, 75 µM for D1d). Tau mutant experiments in Tau biosensor cells lead to the conclusion that D1b acted on the PHF6 and PHF6* segments of Tau. The authors hypothesized that PHF6 and PHF6* might share common structural features with the Aβ core. They could also demonstrate that seeding in Tau biosensor cells by amyloid species in brain-derived tissue from patients with AD or with progressive nuclear palsy could be prevented by D1b (Griner et al. 2019).

Peptides Selected by (Mirror Image) Phage Display or Other

In 2016, the Funke group published the first of a series of articles describing the selection of D-amino acid peptides against Tau or peptides thereof. Phage display selections were performed using fibrils of the D-amino acid hexapeptide VQIVYK (PHF6). The selected D-amino acid peptides bound to PHF6 fibrils, Tau isoform fibrils such as 3RD-Tau (K19), as well as to TauFL fibrils, and modulated the aggregation of the respective Tau form, as demonstrated by ThT-tests and dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Dammers et al. 2016). In silico modelling suggested a binding motif similar to that of the tlkivw-D-peptide, developed by the Eisenberg group to bind PHF6 (Sievers et al. 2011). The D-peptides described by Dammers et al. were able to penetrate cells and slightly reduced the number of ThS-positive cells in an inducible N2aTauRDΔK280 cell culture model. The studies on the D-peptides were not pursued further because of D-peptide-mediated cytotoxicity (Dammers et al. 2016).

The group then employed another mirror-image phage display procedure to identify PHF6* fibril binding D-peptides. The identified D-amino acid peptide MMD3 and its inverse version, designated MMD3rev, inhibited fibrillization of the PHF6* hexapeptide, the repeat domain of Tau as well as TauFL in vitro, as demonstrated by Thioflavin assays. DLS, pelleting assays and atomic force microscopy (AFM) demonstrated that MMD3 prevented the formation of Tau fibrils rich in β-sheets by an interesting mechanism, partitioning Tau into large amorphous aggregates. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) data demonstrated binding of MMD3 and MMD3rev to PHF6*- and TauFL fibrils, while NMR measurements suggested that they bound to monomeric TauFL only with rather low affinity (Malhis et al. 2021). The binding mode to PHF6* fibrils resembled the binding mode of the W-MINK peptide, developed by the Eisenberg group to block PHF6* fibrils (Seidler et al. 2018). The PHF6* targeting peptides MMD3 and MMD3rev identified were able to penetrate neuronal cells (Malhis et al. 2021).

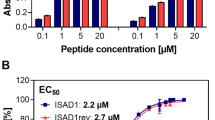

Recently, the group aimed at the generation of D-peptides which bind to TauFL. TauFL binding D-peptides are of great therapeutic interest because they can potentially inhibit aggregation of the Tau protein at the beginning of the fibrillation cascade. The D-peptides binding to TauFL could stabilize the non-toxic and physiologic form and prevent the oligomerization process in the earliest phases of the fibrillization pathway. First, a TauFL binding L-peptide, ISAL1, was selected and synthesized as D- and retro-inverse form (ISAD1 and ISAD1rev). The D-peptides were characterized with respect to their specificity for Tau conformers (monomers and aggregates) and their therapeutic potential. Using ELISA and fluorescein amidite (FAM)-labelled peptides, binding of the peptides to both TauFL and TauFL fibrils was demonstrated. The aggregation-prone hexapeptide motif within Tau, PHF6, was identified as a possible binding site of the most promising D-peptide ISAD1. ISAD1 inhibited fibrillization of TauFL and a wide variety of disease-relevant Tau isoforms (TauRDΔK280, TauFLΔK280, TauFL−A152T, TauFL−P301L). Similar to the D-peptide binding PHF6* described above, it was found that the D-peptides reduced regular Tau fibril formation by forming large non-fibrillar, non-toxic aggregates, which were ThT negative. They were examined in more detail with respect to their particle size in DLS, pelleting assay and western blot. ISAD1 and ISAD1rev were tested in cell culture, where it was evident that the peptides were taken up by neuronal Tau expressing cells and accumulated in the cytosol. The peptides were non-toxic to cells and prevented Tau fibril-mediated cell toxicity of externally added and internally expressed Tau (Aillaud et al. 2022).

In 2020, Zhang and colleagues reported a study similar to that of Dammers et al., 2016. Mirror image phage display was performed on PHF6 fibrils to obtain D-peptides inhibiting the formation of PHF6 fibrils, as demonstrated by ThT assays and EM. The D-peptide p-NH (nitmnsrrrrnh) was able to enter neuronal cells and inhibited Tau hyperphosphorylation and fibrillization. After intranasal application, it improved the cognitive abilities of TauP301S transgenic mice, reducing NFT formation (Zhang et al. 2020).

In 2021, Kondo and colleagues reported on hepta-histidines (7H), which unexpectedly inhibited R3-Tau aggregation in a dose-dependent way, as shown by DLS and EM. 7H was originally investigated as an inhibitor on Ku70 and Huntingtin protein interaction. The peptide transiently contacted Tau at multiple sites with a possible preference for PHF6*. Addition of the trans-activator of transcription (TAT)-sequence to 7H increased its cell permeability. In human neurons differentiated from homozygous TauP301S-induced pluripotent stem (iPS)-cells, (TAT)-7H inhibited Tau phosphorylation at Ser202 and Thr205 (Kondo et al. 2021).

Discussion

Peptides, especially D-amino acid peptides, can be interesting alternatives to small chemical molecules or antibodies. Cell and blood–brain barrier permeability are possible advantages of at least some peptides over therapeutic antibodies, which might have a higher affinity towards their target molecules but cross membranes only poorly (Matsson et al. 2016). Compared to small chemical molecules, the larger binding surface of therapeutic peptides might be of advantage, promising a more successful inhibition of protein–protein interactions (Petta et al. 2016). All of the peptides reviewed here have IC50 values between 1 and 50 µM. The question of whether further optimization of the peptides therapeutic properties might be necessary, will need to be evaluated in animal studies.

As peptides are produced synthetically, they can easily be modified and optimized to fulfil the demands of the pharmaceutical industry. Using methods such as alanine-scans, one can investigate which of the amino acids are essential to perform the desired biological functions (Morrison and Weiss 2001). Amino acid scanning techniques, including pepspot membranes, or molecular modelling approaches allow optimization with respect to e.g. peptide affinity (Funke and Willbold 2012; Eustache et al. 2016; Klein et al. 2016).

Recently, it was demonstrated that therapeutic D-amino acid peptides can be absorbed systematically after oral or intranasal administration (Pappenheimer et al. 1997; Funke et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2020). The Aβ-binding D-peptide D3 (amino acid sequence rprtrlhthrnr) reduced plaque load and cerebral inflammation of AD mouse models after oral treatment, and the cognitive performance was significantly increased if compared to untreated control mice (Funke et al. 2010). D3-derivatives demonstrate excellent blood–brain barrier permeability and were successfully optimized with respect to their therapeutic potential (Jiang et al. 2015; Klein et al. 2016; Leithold et al. 2016). The D3-derivative RD2 recently passed a first clinical study in men (Kutzsche et al. 2020), clinical studies of phase two are planned.

The D3 and RD2 sequences contain arginines, so do the sequences of the D-peptidic TAI p-NH described by Zhang and colleagues (Zhang et al. 2020) and the (TAT)-7H TAI peptide described by Kondo and colleagues (Kondo et al. 2021). Already in 2017, Nadimidla and colleagues found that poly-L arginine hydrochloride inhibited aggregation of PHF6 and a PHF6* containing fragment as well as of Tau mutant protein P301L (Nadimidla et al. 2017). The impact of arginines and arginine-rich peptides is very interesting and was reviewed by Mamsa and Meloni in 2021 in detail (Mamsa and Meloni 2021).

Most of the peptides described as TAI target the PHF6 or the PHF6* sequence motifs of Tau. It remains to be seen which of the sites is the more potent driver for Tau aggregation and therefore the more interesting target for TAI. Seidler and colleagues suggested that PHF6* is the most promising target for the development of TAI (Seidler et al. 2018). In our group, we did not find serious differences in preliminary in vitro studies using D-amino acid peptides selected against PHF6 or PHF6* (Malhis et al. 2021). It is known that in vivo PHF6* within R2 is present in AD patients only in 50% of neuronal Tau (3R vs. 4R Tauopathies, see (Goedert et al. 1989)). Recent cryo-EM studies even demonstrated that Tau fibrils extracted from AD brains have a core composed of R3, R4 and ten residues beyond the end of R4 (Fitzpatrick et al. 2017), suggesting that PHF6 might be the most valuable target for development of TAI. On the other hand, Seidler et al. hypothesized that the core of the fibrils was not the primary driver of aggregation, but might serve as a solvent-excluded scaffold that can cluster PHF6* together in the fuzzy coat, which poises the solvent-exposed VQIINK steric zippers for seeding (Seidler et al. 2018).

Fitzpatrick and colleagues have also shown that Tau filaments extracted from patients with different tauopathies differ in structure (Fitzpatrick et al. 2017). The implications of this and the different TAI described in this review have not yet been tested. Only in vivo studies can answer the question which of the peptides presented in this review will be the most promising leads for AD therapy research. Until now, successful animal studies have only been performed for p-NH as described by Zhang and colleagues (Zhang et al. 2020).

Conclusion

In recent years, a variety of peptide compounds acting as Tau aggregation inhibitors were developed as a promising therapeutic approach towards Alzheimer disease. In particular. the suitability of D-amino acid peptides for possible in vivo applications has already been demonstrated. Most of the peptides already described in the literature were developed by structure-based design or phage display selections. The therapeutic properties of those peptides were summarized in this manuscript. Molecular insight into the binding mode of different peptides was gained by in silico modelling. Some of the identified Tau-targeting peptides were able to penetrate neuronal cells, reduce Tau phosphorylation or improved cognitive abilities of Tau transgenic mice, making them interesting for AD therapy. Future studies are needed to demonstrate which of the peptides can be developed into a therapeutic compound for the treatment of AD.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- 7H:

-

Hepta-histidine

- Aβ:

-

Amyloid-β

- AD:

-

Alzheimer disease

- AFM:

-

Atomic force microscopy

- AGD:

-

Argyrophilic grain disease

- APP:

-

Amyloid-precursor-protein

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- CTE:

-

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy

- D23N:

-

Hereditary mutation in Aβ

- DLS:

-

Dynamic light scattering

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- EM:

-

Electron microscopy

- EYFP:

-

Enhanced yellow fluorescent protein

- FAM:

-

Fluorescein amidite

- FDA:

-

Food and drug administration

- hIAPP:

-

Human islet amyloid-precursor-protein

- HD:

-

Huntington disease

- iPS:

-

Induced pluripotent stem cells

- K18:

-

Construct of 4R Tau

- K19:

-

Construct of 3R Tau

- Ku70:

-

DNA repair subunit protein

- MAPT:

-

Microtubule associated protein Tau

- MicroED:

-

Micro electron diffraction

- MTT:

-

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-didiphenyltetrazolium bromide

- N2a:

-

Neuronal-2a cell line

- NFTs:

-

Neurofibrillary tangles

- NMR:

-

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- P301S:

-

Missense mutation

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- PHFs:

-

Paired helical filaments

- PART:

-

Primary age-related tauopathy

- PS1:

-

Presenilin-1

- PSP:

-

Progressive supranuclear palsy

- R1-4:

-

Microtubule binding repeats 1–4

- RD:

-

Repeat domain

- TAI:

-

Tau aggregation inhibitors

- TAT:

-

Trans-activator of transcription

- TauFL :

-

Full-length human Tau (441 amino acids)

- TauRDΔK :

-

Pro-aggregant repeat domain Tau mutant ΔK280

- TauFLΔK :

-

Full-length Tau mutant ΔK280

- TauFL − A152T :

-

Full-length Tau mutant A152T

- TauFL − P301L :

-

Full-length Tau mutant P301L

- TEM:

-

Transmission electron microscopy

- ThT:

-

Thioflavin-T

- ThS:

-

Thioflavin-S

References

Aillaud I, Kaniyappan S, Chandupatla RR, Ramirez LM, Alkhashrom S, Eichler J, Horn AH, Zweckstetter M, Mandelkow E, Sticht H, Funke SA (2022) A novel D-amino acid peptide with therapeutic potential, designated ISAD1, inhibits aggregation of disease relevant pro-aggregant mutant Tau and prevents Tau toxicity in vitro. Alzheimers Res Ther 14:15

Alzheimer A, Stelzmann RA, Schnitzlein HN, Murtagh FR (1995) An English translation of Alzheimer’s 1907 paper, “Über eine eigenartige Erkankung der Hirnrinde.” Clin Anat 8:429–431. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.980080612

Arendt T, Stieler JT, Holzer M (2016) Tau and tauopathies. Brain Res Bull 126:238–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.08.018

Barghorn S, Davies P, Mandelkow E (2004) Tau Paired helical filaments from Alzheimer’s disease brain and assembled in vitro are based on β-structure in the core domain †. Biochemistry 43:1694–1703. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi0357006

Braak H, Braak E (1991) Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 82:239–259

Bulic B, Pickhardt M, Mandelkow E (2013) Progress and developments in tau aggregation inhibitors for Alzheimer disease. J Med Chem 56:4135–4155. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm3017317

Chalifour RJ, McLaughlin RW, Lavoie L, Morissette C, Tremblay N, Boulé M, Sarazin P, Stéa D, Lacombe D, Tremblay P, Gervais F (2003) Stereoselective interactions of peptide inhibitors with the beta-amyloid peptide. J Biol Chem 278:34874–34881. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M212694200

Cummings J, Lee G, Ritter A, Zhong K (2018) Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2018. Alzheimers Dement (NY) 4:195–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trci.2018.03.009

Dammers C, Yolcu D, Kukuk L, Willbold D, Pickhardt M, Mandelkow E, Horn AHC, Sticht H, Malhis MN, Will N, Schuster J, Funke SA (2016) Selection and characterization of Tau binding -enantiomeric peptides with potential for therapy of Alzheimer disease. PLoS ONE 11:e0167432. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167432

Danho W, Swistok J, Khan W, Chu X-J, Cheung A, Fry D, Sun H, Kurylko G, Rumennik L, Cefalu J, Cefalu G, Nunn P (2009) Opportunities and challenges of developing peptide drugs in the pharmaceutical industry. Adv Exp Med Biol 611:467–469

Eustache S, Leprince J, Tufféry P (2016) Progress with peptide scanning to study structure-activity relationships: the implications for drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov 11:771–784. https://doi.org/10.1080/17460441.2016.1201058

Fitzpatrick AWP, Falcon B, He S, Murzin AG, Murshudov G, Garringer HJ, Crowther RA, Ghetti B, Goedert M, Scheres SHW (2017) Cryo-EM structures of tau filaments from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 547:185–190. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature23002

Friedhoff P, von Bergen M, Mandelkow EM, Davies P, Mandelkow E (1998) A nucleated assembly mechanism of Alzheimer paired helical filaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:15712–15717

Funke SA, Willbold D (2012) Peptides for therapy and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Pharm Des 18:755–767

Funke SA, van Groen T, Kadish I, Bartnik D, Nagel-Steger L, Brener O, Sehl T, Batra-Safferling R, Moriscot C, Schoehn G, Horn AHC, Müller-Schiffmann A, Korth C, Sticht H, Willbold D (2010) Oral treatment with the d-enantiomeric peptide D3 improves the pathology and behavior of Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice. ACS Chem Neurosci 1:639–648. https://doi.org/10.1021/cn100057j

Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Jakes R, Rutherford D, Crowther RA (1989) Multiple isoforms of human microtubule-associated protein tau: sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 3:519–526

Griner SL, Seidler P, Bowler J, Murray KA, Yang TP, Sahay S, Sawaya MR, Cascio D, Rodriguez JA, Philipp S, Sosna J, Glabe CG, Gonen T, Eisenberg DS (2019) Structure-based inhibitors of amyloid beta core suggest a common interface with Tau. Elife. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.46924

Guo JL, Lee VM-Y (2011) Seeding of normal Tau by pathological Tau conformers drives pathogenesis of Alzheimer-like tangles. J Biol Chem 286:15317–15331. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M110.209296

Guo J-P, Arai T, Miklossy J, McGeer PL (2006) Abeta and tau form soluble complexes that may promote self aggregation of both into the insoluble forms observed in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:1953–1958. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0509386103

Hanseeuw BJ, Betensky RA, Jacobs HIL, Schultz AP, Sepulcre J, Becker JA, Cosio DMO, Farrell M, Quiroz YT, Mormino EC, Buckley RF, Papp KV, Amariglio RA, Dewachter I, Ivanoiu A, Huijbers W, Hedden T, Marshall GA, Chhatwal JP, Rentz DM, Sperling RA, Johnson K (2019) Association of amyloid and tau with cognition in preclinical Alzheimer disease: a longitudinal study. JAMA Neurol 76:915–924. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1424

Henninot A, Collins JC, Nuss JM (2018) The current state of peptide drug discovery: back to the future? J Med Chem 61:1382–1414. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00318

Holmes BB, Diamond MI (2014) Prion-like properties of Tau protein: the importance of extracellular Tau as a therapeutic target. J Biol Chem 289:19855–19861. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.R114.549295

Iqbal K, Del Alonso AC, Chen S, Chohan MO, El-Akkad E, Gong C-X, Khatoon S, Li B, Liu F, Rahman A, Tanimukai H, Grundke-Iqbal I (2005) Tau pathology in Alzheimer disease and other tauopathies. Biochim Biophys Acta 1739:198–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.09.008

Jiang N, Leithold LHE, Post J, Ziehm T, Mauler J, Gremer L, Cremer M, Schartmann E, Shah NJ, Kutzsche J, Langen K-J, Breitkreutz J, Willbold D, Willuweit A (2015) Preclinical pharmacokinetic studies of the tritium labelled D-enantiomeric peptide D3 developed for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 10:e0128553. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128553

Johnson KA, Schultz A, Betensky RA, Becker JA, Sepulcre J, Rentz D, Mormino E, Chhatwal J, Amariglio R, Papp K, Marshall G, Albers M, Mauro S, Pepin L, Alverio J, Judge K, Philiossaint M, Shoup T, Yokell D, Dickerson B, Gomez-Isla T, Hyman B, Vasdev N, Sperling R (2016) Tau positron emission tomographic imaging in aging and early Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 79:110–119. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24546

Klein AN, Ziehm T, Tusche M, Buitenhuis J, Bartnik D, Boeddrich A, Wiglenda T, Wanker E, Funke SA, Brener O, Gremer L, Kutzsche J, Willbold D (2016) Optimization of the all-D peptide D3 for abeta oligomer elimination. PLoS ONE 11:e0153035. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153035

Knopman DS, Jones DT, Greicius MD (2021) Failure to demonstrate efficacy of aducanumab: an analysis of the EMERGE and ENGAGE trials as reported by biogen, December 2019. Alzheimers Dement 17:696–701. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12213

Kondo K, Ikura T, Tanaka H, Fujita K, Takayama S, Yoshioka Y, Tagawa K, Homma H, Liu S, Kawasaki R, Huang Y, Ito N, Tate S-I, Okazawa H (2021) Hepta-histidine inhibits Tau aggregation. ACS Chem Neurosci 12:3015–3027. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.1c00164

Kuhlman B, Dantas G, Ireton GC, Varani G, Stoddard BL, Baker D (2003) Design of a novel globular protein fold with atomic-level accuracy. Science 302:1364–1368. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1089427

Kumar S, Tepper K, Kaniyappan S, Biernat J, Wegmann S, Mandelkow EM, Müller DJ, Mandelkow E (2014) Stages and conformations of the Tau repeat domain during aggregation and its effect on neuronal toxicity. J Biol Chem 289:20318–20332. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.554725

Kutzsche J, Jürgens D, Willuweit A, Adermann K, Fuchs C, Simons S, Windisch M, Hümpel M, Rossberg W, Wolzt M, Willbold D (2020) Safety and pharmacokinetics of the orally available antiprionic compound PRI-002: a single and multiple ascending dose phase I study. Alzheimers Dement (NY) 6:e12001. https://doi.org/10.1002/trc2.12001

Lasagna-Reeves CA, Castillo-Carranza DL, Sengupta U, Clos AL, Jackson GR, Kayed R (2011) Tau oligomers impair memory and induce synaptic and mitochondrial dysfunction in wild-type mice. Mol Neurodegener 6:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1326-6-39

Lee AC-L, Harris JL, Khanna KK, Hong J-H (2019) A comprehensive review on current advances in peptide drug development and design. Int J Mol Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20102383

Leithold LHE, Jiang N, Post J, Ziehm T, Schartmann E, Kutzsche J, Shah NJ, Breitkreutz J, Langen K-J, Willuweit A, Willbold D (2016) Pharmacokinetic properties of a novel D-peptide developed to be therapeutically active against toxic beta-amyloid oligomers. Pharm Res 33:328–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-015-1791-2

Lien S, Lowman HB (2003) Therapeutic peptides. Trends Biotechnol 21:556–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2003.10.005

Liu H, Funke SA, Willbold D (2010) Transport of Alzheimer disease amyloid-beta-binding D-amino acid peptides across an in vitro blood-brain barrier model. Rejuvenation Res 13:210–213. https://doi.org/10.1089/rej.2009.0926

Liu M, Li X, Xie Z, Xie C, Zhan C, Hu X, Shen Q, Wei X, Su B, Wang J, Lu W (2016) D-peptides as recognition molecules and therapeutic agents. Chem Rec 16:1772–1786. https://doi.org/10.1002/tcr.201600005

Lovestone S, Manji HK (2020) Will we have a drug for Alzheimer’s disease by 2030? The view from pharma. Clin Pharmacol Ther 107:79–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.1685

Malhis M, Kaniyappan S, Aillaud I, Chandupatla RR, Ramirez LM, Zweckstetter M, Horn AHC, Mandelkow E, Sticht H, Funke SA (2021) Potent Tau aggregation inhibitor D-peptides selected against Tau-repeat 2 using mirror image phage display. ChemBioChem 22:3049–3059. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.202100287

Mamsa SSA, Meloni BP (2021) Arginine and arginine-rich peptides as modulators of protein aggregation and cytotoxicity associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Front Mol Neurosci 14:759729

Matsson P, Doak BC, Over B, Kihlberg J (2016) Cell permeability beyond the rule of 5. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 101:42–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2016.03.013

Miller Y, Ma B, Nussinov R (2011) Synergistic interactions between repeats in tau protein and Aβ amyloids may be responsible for accelerated aggregation via polymorphic states. Biochem 50:5172–5181. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi200400u

Morris M, Maeda S, Vossel K, Mucke L (2011) The many faces of Tau. Neuron 70:410–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.009

Morrison KL, Weiss GA (2001) Combinatorial alanine-scanning. Curr Opin Chem Biol 5:302–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00206-4

Mullard A (2021) FDA approval for Biogen’s aducanumab sparks Alzheimer disease firestorm. Nat Rev Drug Discov 20:496. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41573-021-00099-3

Nadimidla K, Ismail T, Kanapathipillai M (2017) Tau peptides and tau mutant protein aggregation inhibition by cationic polyethyleneimine and polyarginine. Biopolymers. https://doi.org/10.1002/bip.23024

Nisbet RM, Polanco JC, Ittner LM, Götz J (2015) Tau aggregation and its interplay with amyloid-β. Acta Neuropathol 129:207–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-014-1371-2

Pappenheimer JR, Karnovsky ML, Maggio JE (1997) Absorption and excretion of undegradable peptides: role of lipid solubility and net charge. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 280:292–300

Petta I, Lievens S, Libert C, Tavernier J, de Bosscher K (2016) Modulation of protein-protein interactions for the development of novel therapeutics. Mol Ther 24:707–718. https://doi.org/10.1038/mt.2015.214

Pourhamzeh M, Joghataei MT, Mehrabi S, Ahadi R, Hojjati SMM, Fazli N, Nabavi SM, Pakdaman H, Shahpasand K (2021) The interplay of Tau protein and β-amyloid: while tauopathy spreads more profoundly than amyloidopathy, both processes are almost equally pathogenic. Cell Mol Neurobiol 41:1339–1354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10571-020-00906-2

Roe CM, Fagan AM, Grant EA, Hassenstab J, Moulder KL, Maue Dreyfus D, Sutphen CL, Benzinger TLS, Mintun MA, Holtzman DM, Morris JC (2013) Amyloid imaging and CSF biomarkers in predicting cognitive impairment up to 7.5 years later. Neurology 80:1784–1791. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182918ca6

Sadowski M, Pankiewicz J, Scholtzova H, Ripellino JA, Li Y, Schmidt SD, Mathews PM, Fryer JD, Holtzman DM, Sigurdsson EM, Wisniewski T (2004) A synthetic peptide blocking the apolipoprotein E/beta-amyloid binding mitigates beta-amyloid toxicity and fibril formation in vitro and reduces beta-amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Am J Pathol 165:937–948

Schumacher TN, Mayr LM, Minor DL, Milhollen MA, Burgess MW, Kim PS (1996) Identification of D-peptide ligands through mirror-image phage display. Science 271:1854–1857

Seidler PM, Boyer DR, Rodriguez JA, Sawaya MR, Cascio D, Murray K, Gonen T, Eisenberg DS (2018) Structure-based inhibitors of tau aggregation. Nature Chem 10:170–176. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.2889

Selkoe DJ, Hardy J (2016) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol Med 8:595–608. https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.201606210

Sievers SA, Karanicolas J, Chang HW, Zhao A, Jiang L, Zirafi O, Stevens JT, Münch J, Baker D, Eisenberg D (2011) Structure-based design of non-natural amino-acid inhibitors of amyloid fibril formation. Nature 475:96–100. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10154

Soeda Y, Takashima A (2020) New insights into drug discovery targeting Tau protein. Front Mol Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2020.590896

von Bergen M, Friedhoff P, Biernat J, Heberle J, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E (2000) Assembly of tau protein into Alzheimer paired helical filaments depends on a local sequence motif ((306)VQIVYK(311)) forming beta structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:5129–5134

von Bergen M, Barghorn S, Li L, Marx A, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E (2001) Mutations of tau protein in frontotemporal dementia promote aggregation of paired helical filaments by enhancing local beta-structure. J Biol Chem 276:48165–48174. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M105196200

Walsh S, Merrick R, Milne R, Brayne C (2021) Aducanumab for Alzheimer’s disease? BMJ 374:n1682. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1682

Wang Y, Mandelkow E (2016) Tau in physiology and pathology. Nat Rev Neurosci 17:5–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2015.1

Wang L, Bharti KR, Pavlov PF, Winblad B (2021) Small molecule therapeutics for tauopathy in Alzheimer’s disease: walking on the path of most resistance. Eur J Med Chem 209:112915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112915

World Alzheimer Report (2021) Alzheimer’s disease international

Zhang X, Zhang X, Zhong M, Zhao P, Guo C, Li Y, Wang T, Gao H (2020) Selection of a d-enantiomeric peptide specifically binding to PHF6 for inhibiting Tau aggregation in transgenic mice. ACS Chem Neurosci 11:4240–4253. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00518

Acknowledgements

We thank Richard Fry for revision of English language.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by a grant (no. 17001) of Alzheimer Forschung Initiative e.V. (AFI) to SAF, a grant of TechnologieAllianzOberfranken (TAO) to IA and a scholarship of Landeskonferenz der Frauenbeauftragten (LaKoF), Bavaria, Germany, to IA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors have contributed to the manuscript text and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aillaud, I., Funke, S.A. Tau Aggregation Inhibiting Peptides as Potential Therapeutics for Alzheimer Disease. Cell Mol Neurobiol 43, 951–961 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10571-022-01230-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10571-022-01230-7