Abstract

In this work, the influence of the supermolecular structure of cellulosic fillers in chitosan matrix on the process of adsorption of calcium, magnesium and iron metal ion was analyzed, while using techniques such as: X-ray diffraction, flame atomic absorption spectrometry, FTIR spectroscopy, particle size analysis, and wettability angle. It has been shown that polymorphic form of cellulose significantly affects its particle size. The introduction of cellulosic filler into polymer matrix was responsible for changes in the sorption efficiency of chitosan composites. It was found that materials with nanocellulose II were characterized with the highest efficiency of adsorption. This interesting relationship has not been reported in the literature, yet. It is important especially in terms of designing composite materials with high adsorption capacity. In the presented paper this issue was discussed, taking into account crystallographic aspects as well as changes in the hydrophilicity of the surface of composite materials. Composite materials were also subjected to mechanical tests which showed some interesting increase in tensile strength when compared to the unfilled polymer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metal contamination of the environment is a serious problem because metals can be toxic, even in small amounts. Moreover, metals are non-biodegradable, they accumulate in living organisms and pose a great threat to health and life (Crini 2005).

Even metals such as magnesium and calcium, which are moved into the groundwater together with fertilizers, can limit the adsorption of other, needful elements. Thanks to water treatment processes it is possible to decrease the amount of Ca(II), Mg(II), and Fe(III) ion in water. However, diverse composition of industrial wastewater requires a variety of treatment methods, e.g. precipitation, oxidation and reduction, filtration, centrifugation, reverse osmosis, sedimentation, solvent extraction, evaporation, reverse osmosis flotation, electro-chemical removal, evaporative recovery, adsorption, etc. (Chong and Volesky 1995; Bhattacharyya and Gupta 2008; Mahvi 2008; Peijnenburg et al. 2015). Also ion exchange and sorption methods are eagerly used. The adsorption process is considered as one of the best water treatment methods due to the wide availability of different types of adsorbents. Popular adsorbents include: activated carbon (Hu et al. 2003), zeolites (Bosso and Enzweiler 2002), clays (Abollino et al. 2003), silica (Ghoul et al. 2003), biomass (Loukidou et al. 2003).

Unfortunately, it should be emphasized that main limitation of sorption methods is economic, due to high costs of adsorbents, as well as high costs of the sorbent regeneration process (Cestari et al. 2004; Alade et al. 2012). Thus, newly developed adsorbent should be not only effective but also relatively cheap.

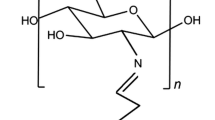

There are some biopolymers such as chitin, chitosan, sodium alginate that are characterized by good adsorption of heavy metals. A particularly interesting biopolymer is chitosan, which is a biodegradable, biocompatible, and antibacterial material. There are many reports reporting its application for sorption of various metals, e.g. Cr(VI) (Aydin and Aksoy 2009), Pb(II) (Leusch et al. 1995), Cu(II) (Negm et al. 2015), Hg(II) (Allouche et al. 2014), Cd(II) (Kyzas et al. 2014), Ni(II) (Heidari et al. 2013), Zn(II) (Milosavljevic et al. 2011), Co(II) (Minamisawaa et al. 1999), Mn(II) (Al-Wakeel et al. 2015). Sorption properties are a result of the formation of coordination bonds between amine groups of chitosan and heavy metal ion. It has been shown that the sorption activity of chitosan depends on the degree of crystallinity, the degree of deacetylation, and the content of amine groups. However, membranes made from pure chitosan are very brittle (Chatterjee et al. 2009), have low acid resistance (Zhou et al. 2009), low thermal stability (Cirini and Badot 2008), as well as low porosity and specific surface (Vakili et al. 2014). To eliminate these drawbacks and increase the efficiency of metal ion binding, a number of chemical or physical modifications of chitosan were carried out (Yang and Yuan 2001; Zhang and Chen 2002; Varma et al. 2004; Crini 2005; Bhatnagar and Sillanpaa 2009; Miretzky and Cirelli 2009; Boamah et al. 2015; Kumar et al. 2019).

Methods of chemical modification rely mainly on grafting and cross-linking reactions. Since cross-linking agents form covalent bonds with amine groups in chitosan the effect of this type of modification is an increase in the mechanical strength and chemical stability of chitosan membranes (Guibal 2004). Another method to increase sorption capacity is functionalization of chitosan by introducing new functional groups (Jayakumar et al. 2005; Vakili et al. 2014). Modification of chitosan properties can also be obtained by adding plasticizing compounds, e.g. polyethylene glycol, polyvinylpyrrolidone (Zeng and Fang 2004).

Recently, adsorption of heavy metals and dyes from wastewater with use of chitosan composites have aroused great interest. To date, many different fillers have been used, such as silica (Kalapathy et al. 2000), montmorillonite (Wang and Wang 2007), and kaolinite (Zhu et al. 2010). The introduction of fillers often results in increased porosity, specific surface, swelling and diffusivity (Zhang et al. 2016). Vijaya et al. (2008) dealt with the removal of Ni(II) ion using chitosan coated calcium alginate and chitosan coated silica. Also Ghaee et al. (2010) noted that increasing the silica content in chitosan resulted in increased porosity and at the same time copper ion adsorption efficiency. There are several work in which chitosan and perlite composites were used to adsorb metals such as Co(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) (Kalyani et al. 2009). Composites of chitosan and cotton that were reported to remove Au(II), Pb(II), Ni(II), Cd(II), and Cu(II), too (Zhang et al. 2008; Qu et al. 2009).

Particularly interesting material in terms of production of adsorbents is cellulose, a biopolymer containing β-1,4 glycosidic linked D-glucose units. It is insoluble in water and organic solvents that has a large number of functional groups, enabling its functionalization. There are several studies that used cellulose immobilization on chitosan. Sun et al. (2009) observed that the adsorption efficiency of chitosan was almost three times higher than that of chitosan and cellulose composite systems, although the polymer composite was more stable. Li and Bai (2005) noted that the crosslinking reaction between chitosan and cellulose improves acid resistance. Urbina et al. (2018) obtained chitosan membranes with bacterial cellulose for removing copper ion from aqueous wastewater. They found that composites had better mechanical properties as well as greater copper ion removal efficiency. Vinodhini et al. (2017) proved that a higher content of chitosan in chitosan/cellulose acetate material is responsible for achieving greater efficiency in removing metal ion, what is a result of higher content of amorphous phase.

Our previous research has shown that the mechanical properties of chitosan/cellulose composites depend on the content of the nanometer fraction of fillers. As a result of the design and synthesis of ionic liquids and their use for cellulose modification, it is possible to obtain composite materials with controllable strength properties, e.g. composites with high elasticity and at the same time high breaking stress (Grząbka-Zasadzińska et al. 2019). These strength characteristics are extremely important in terms of designing new adsorbents.

The most popular polymorphic form of cellulose is so called native cellulose (cellulose I). However, some chemical processes, like mercerization, are known to be responsible for change of polymorphic from of cellulose I into cellulose II. The dissimilarity of cellulose II may exert a beneficial effect on some properties of fillers. It is known that the mechanical, dispersive, and morphological properties of composites are related to the polymorphic form of the cellulosic filler (Grząbka-Zasadzińska et al. 2018). We have shown many times, that the type of cellulose polymorph is a factor that not only determines the mechanical properties of composites, but also affects the supermolecular structure, morphology, phase transformation processes and topography of polymer composites (Borysiak 2012, 2013a).

The main purpose of this work was to analyze the influence of polymorphic form of cellulose and its particle size in chitosan matrix on the effectiveness of selected metal ion removal. To the best of our knowledge, these relationships have not yet been studied. Analysis of these issues is important to understand the relationship between supermolecular structure and the adsorption and mechanical properties of composite materials. This relationship is also believed to help to understand the mechanism of the adsorption process in biocomposites.

Experimental

Materials

Two types of cellulose were used in this work – Avicel PH-101 and Arbocel UFC 100 BRIGHT. Avicel PH-101 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Arbocel UFC 100 BRIGHT was supplied by J. Rettenmaier and Söhne. High molecular weight chitosan from crab shells (degree of deacetylation 75–85%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Pure sodium hydroxide, provided by Chempur, was used for preparation of 16% solution and subsequently used as mercerizing agent. Acetic acid 80%, purchased from POCH S.A., was diluted to 2% (v/v) solution and used for composite formation.

Salts (Ca(NO3)2 · 4H2O, Mg(NO3)2 · 6H2O, FeCl3 · 6H2O) used to prepare of aqueous solution of Ca(II), Mg(II) and Fe(III), respectively, were purchased from Avantor Performance Materials. Nitric acid and standard solutions of metals for AAS determination were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Native cellulose materials, before mercerization process, were named accordingly: Avicel PH-101 as cellulose I (C I) and Arbocel UFC 100 BRIGHT as nanocellulose I (CNC I).

Chemical modification of cellulose

Cellulose I was treated with 16% NaOH at room temperature. After 5 min of continuous stirring an excess of water was added to stop the mercerization process. The suspension was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. Finally, the produced cellulose II (C II) was washed with the excess of distilled water to remove NaOH and then dried in the air at 70 °C for 6 h. The same mercerization procedure was carried out for nanocellulose I. In result material named CNC II was obtained.

Preparation of cellulose/chitosan composites

Chitosan/(nano)cellulose composites were produced by solvent casting method. Firstly, chitosan was dissolved in 2% (v/v) CH3COOH. Secondly, suspension of (nano)cellulose (5% (w/w) of filler, in relation to dry mass of chitosan) in acetic acid was slowly added to chitosan solution, stirred for 5 min at 3000 rpm, and then homogenized using ultrasonic bath (30 min at 40 kHz, 100% power without heating). Mixtures were applied on Petri dishes and dried for 12 h at 35 °C. Obtained films were homogenous, no holes or big agglomerates were present.

Samples were named for ease of experiments and film characterization such as CHT/CNC I where stands for chitosan composite with 5% loading of nanocrystalline cellulose I.

Metal ion adsorption process

The sorption properties of chitosan membrane and cellulose/chitosan composites were performed using aqueous solutions of individual ion – magnesium(II), calcium(II) and iron(III) at a concentration 0.1 mM. The membrane samples at weight of 0.1 ± 0.0001 g were put into glass vials containing 10 mL of metal solution. The pH value during experiment was 5. The studies by Mahatmanti et al. (2016) showed that ion adsorption by chitosan is most effective for pH in the range 5–6. The choice of this pH solution is also confirmed by Gedam et al. (2018), in which the influence of the pH of solution on the adsorption process was studied. On the basis of a review of work of Mahatmanti et al (2016) and Gedam et al. (2018), it was assumed that at the chosen pH 5 the adsorption process occurs under optimal conditions for most elements. Based on the results of the study on the kinetics of the adsorption process, described in the paper Kaveeshwar et al. (2017), and Wu et al. (2010), in this paper aqueous solutions of nitrate (V) salts of alkali metals Ca(II), Mg(II) and sulphate (VI) heavy metal Fe(III), at the lowest concentration were studied.

After 1 h, the membranes were removed from metal solutions, put on Petri dishes and dried for 2 h at 95 °C.

Characterization of cellulosic fillers and composite materials

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

Before characterization samples were freeze-dried at – 50 °C, vacuum 0.33 mbar (Christ, model Alpha 1–2 LDplus). Materials were analyzed by means of X-ray diffraction using CuKα radiation at 30 kV and 25 mA anode excitation. The X-ray diffraction patterns were recorded for the angle range of from 5 to 40° in the step of 0.05°/3 s. Deconvolution of peaks was performed by the method proposed by Hindeleh and Johnson (1971), improved and programmed by Rabiej (1991).

Particle size

Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments Ltd.) employing the laser diffraction technique in the range of 0.6–6000 nm was applied to determine particle size and the dispersive properties of (nanometric) celluloses.

Flame atomic absorption spectrometry—FAAS

The samples of chitosan membrane and cellulose/chitosan composites at weight 0.5 g were mineralized with nitric acid (8 mL) in a semi-closed microwave mineralization MARSXpress system (CEM Corporation). After mineralization process, solutions were filtered and diluted of deionized water to 50 mL. The content of Mg, Ca, Fe in the samples was analyzed by means of FAAS, using a Spectra 280 AA spectrometer (Agilent Technologies). The calibration curve was prepared from the serial dilutions of standard solutions of examined elements. The final results were average values of three simultaneous measurements.

FTIR spectroscopy—attenuated total reflection (ATR)

Spectra were registered using a Nicolet iS5 spectrophotometer by Thermo Fisher Scientific with Fourier transform at a range of 4000–500 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1, registering 32 scans.

Wettability angle

Measurements of contact angle (CA) with water were carried out using Dataphysics OCA 200 instrument. All measurements were carried out at 298 ± 0.1 K. A drop of 0.2 µL was automatically pushed out of the capillary and deposited on a solid surface of the sample.

Tensile properties

Tensile properties of produced composite films were defined using Zwick and Roell Allround-Line Z020 TEW testing machine. Samples of 10 mm width and thickness ca.100 µm were tested with speed 5 mm/min and initial force 0.2 N in accordance to standard ISO 527–3. The arithmetic mean of seven replicate determinations was taken into consideration in each case.

Results and discussion

Supermolecular structure of fillers

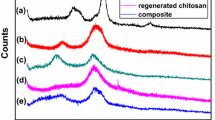

WAXS technique was used to assess supermolecular structure of cellulosic fillers. An analysis of patterns shown in Figs. 1 and 2. confirm that the polymorphic conversion from C I into C II and CNC I into CNC II was successful. Deconvolutions of all XRD patterns are presented in Supplementary Materials.

Figures 1 and 2 show diffractograms of samples with peaks assigned to respective crystallographic planes. The X-ray patterns for C I and CNC I samples indicate the occurrence of peaks at angles of 2Ө = 15°; 16.5°; 22.5° and 34.5° (French 2014).

After mercerization (C II and CNC II samples) the diffraction patterns have changed. Theoretically, in mercerized samples the first peak, coming from (-110) plane, should be located at 2Ө = 12.5°(French 2014). Although, in this study we observed only a very broad peak at ca. 14°. This was quite surprising and unfortunately, we found no fully convincing reason for that. It seems possible that this one, broad peak is a result of overlapping two peaks from (1-10) and (110) planes, originating from cellulose I that was not fully converted to cellulose II. However, if that was a case, we should also observe peak at 2Ө = 22.5°, which was not present. Thus, this issue remains unsolved.

For C II and CNC II all other peaks were in line with literature data (French 2014). The crystalline peak at 2Ө = 23° disappeared and instead two weaker peaks at 2Ө = 20° and 2Ө = 22° were observed. These peaks came from the lattice planes (110) and (200) or (020), respectively. That indicates formation of (nano)cellulose II and proves that the use of 16% aqueous NaOH solution allowed for conversion of cellulose I into cellulose II. This is consistent with literature reports which show that the use of NaOH with a concentration higher than 10% allows for effective conversion of native cellulose into cellulose II (Yue et al. 2013).

Another aspect, in addition to the polymorphic conversion that occurs during the mercerization process, is the reduction in the degree of crystallinity. This is due to the conversion of some crystalline regions into amorphous ones. The results of the research show also that mercerization was responsible for some reduction in the degree of crystallinity. For micrometric cellulose I and cellulose II it was ca. 70% and 47%, respectively. For nanometric cellulose I it was 68% versus 43% for nanometric cellulose II. The existence of a similar relationship was also demonstrated in other publications (Yue et al. 2013). What is interesting, polymorphic conversion was slightly more efficient in nanometric samples.

X-ray studies confirmed the polymorphic conversion of cellulose, which allowed in the next stage for analysis of the effect of crystal structure of cellulose on efficiency of removal of metals ion, which effect has not been studied so far.

Particle size of fillers

Studies on the size distribution of particles showed a relationship between the crystallographic modification and the size of cellulose particles. Particle size distributions of cellulose I and cellulose II were already presented in our previous studies (Grząbka-Zasadzińska et al. 2018). It showed that mercerization process caused the decrease in particle sizes from ~ 48 µm for C I up to ~ 40 µm for C II.

Results obtained for CNC I and CNC II are given in Fig. 3.

For CNC I a significant amount of the micrometer fraction was noted. Particles were also characterized with wide distribution of particle size (78.8–4800 nm). However, particles with diameter between 78.8 nm and 142 nm accounted for 58.6% of the sample. It should also be emphasized that according to the accepted IUPAC nomenclature, nanofillers are materials in which at least one dimension does not exceed 100 nm. However, in the presented work Arbocel UFC 100 BRIGHT was named as CNC I. The adopted nomenclature resulted from significant disproportions in the particle size of the analyzed materials, and its introduction primarily served to distinguish particles with a size close to 100 nm from cellulose with a clearly micrometric dimension ≥ 2670 nm.

The obtained results of particle size distribution for CNC II showed that the mercerization process led to the reduction of particle size and the obtained filler was characterized by a much narrower range of particle diameters (50.8–142 nm). It is worth emphasizing that no micrometer fraction was found for this filler. The mercerization process of CNC I resulted in both polymorphic conversion of cellulose and also obtaining only the nanometric fraction (below 150 nm).

Sorption process

The concentration of magnesium, calcium, and iron adsorbed by chitosan film and cellulose/chitosan composites determined by means of FAAS is presented in Table 1.

The results given in Table 1 prove that all tested samples demonstrated ability of sorption of Ca(II), Mg(II) and Fe(III) from aqueous solutions. The most effective sorption was observed for calcium ion. Among tested samples, the most effective sorption ability with regard to all metal ion was observed for CHT/CNC II. The sorption efficiency of this composite was higher than for chitosan membrane about four, two, and five times as regard to Mg(II), Ca(II), and Fe(III), respectively. Satisfactory results of Ca(II) sorption were observed also for chitosan with cellulose I (CHT/C I). Moreover, all tested composites were characterized with higher sorption of Ca(II) and Fe(III) than chitosan membrane itself. Materials containing cellulose I (CHT/C I) showed higher sorption properties as regard to Ca(II) and Mg(II) than composite with cellulose II (CHT/C II). On the contrary, composite containing nanocellulose I (CHT/CNC I) adsorbed less of Ca(II) and Mg(II) than composite with nanocellulose II (CHT/CNC II). These results indicated that crystal form of cellulose influences on its sorption properties.

Sorption properties of chitosan-based composites depend on the type of the filler used. The sorption ability of chitosan membrane blended with rice hull ash silica and polyethylene glycol as regard to Ca(II) was reported to be lower than to Mg(II) (Mahatmanti et al. 2016). On the other hand, the sorption properties of chitosan-alginate membrane were found to be higher as regard to Ca(II) than Mg(II) (Cahyaningrum and Herdyastuti 2011).

The sorption of Fe(III) by cellulose/chitosan composites was lower than sorption of Ca(II) and Mg(II), but it was more effective than for chitosan. Sorption of Fe(III) for composites was 2.5 and 4.8 times higher, for CHT/C I and CHT/CNC II, respectively, than chitosan membrane. The results obtained by Radomski et al. (2014) indicated that chitosan/aspartic acid copolymer cured with ethylene glycol showed lower sorption ability as regard iron ion (0.140 mg g−1) than chitosan (0.240 mg g−1). It is worth emphasizing that all composites examined in this paper have achieved higher concentration of adsorbed iron. CHT/CNC II composite adsorbed over five times more iron than materials tested by Radomski et al. (2014).

The FTIR spectra of pure chitosan sample (A) and metal loaded forms (B-F) shown in Figs. 4, 5 and 6 confirm AAS results presented in Table 1.

The interpretation of FTIR spectrum of pure chitosan based on literature data are presented in Table 2 (Silva et al. 2012; Soundarrajan et al. 2013; Zhao et al. 2014; Okoya and Adeodun 2017).

Figures 4, 5 and 6 (B-F) show the FTIR spectra of cellulose/chitosan composites loaded with Ca(II), Mg(II), and Fe(III) ion. An interesting phenomenon is the shift in the position and intensity of the bands after metal binding. The FTIR spectra of CHT/CNC II biosorbent indicate the presence of predominant peaks at 3355 cm−1 (–OH and –NH stretching vibrations), 2927 cm−1 (–CH stretching vibration), 1538 cm−1 (–NH bending vibration), 1380 cm−1 (–NH deformation vibration), and 1064 cm−1 (–CO stretching vibration). This reveals that all functional groups originally present in chitosan and its composites are still present, even after interaction with Ca(II), Mg(II), and Fe(III) ion (Vijaya et al. 2008).

The FTIR spectra of the cellulose/chitosan composites after adsorption were very similar to the spectra of unfilled chitosan after adsorption. However, some noticeable differences have been observed in the intensity of bands. Namely, the peak at 3355 cm−1, corresponding to the stretching vibrations of –OH and –NH2 became broader and of higher intensity, indicating some interaction between these groups and Ca(II), Mg(II), and Fe(III) ion. Bands near 1064 cm−1 in pure chitosan are usually attributed to the C–O and C–N stretching vibrations. The intensity of these characteristic bands significantly decreased in the spectrum of the CHT/CNC II complex with calcium, magnesium, and iron, indicating that C–O and C–N groups are involved in coordination of these ion. Moreover, bands appearing in spectra in the range of 615 and 558 cm−1 can be attributed to the stretching vibrations of N–Ca, Mg or Fe and O–Ca, Mg or Fe (Perelshtein et al. 2013).

In Mahatmanti’s paper (Mahatmanti et al. 2016) a mechanism of binding various metal ion by chitosan was proposed. In comparison to zinc, calcium and magnesium ion were adsorbed less effectively. The authors explain that ionic bond between calcium and magnesium ion and hydroxyl and amino groups in chitosan is unstable and breaks easily, especially in a polar solvent, e.g. water. However, the other work (Piątkowski et al. 2010) showed that magnesium and calcium do not react with chitosan or these interactions are too weak to stabilize the resulting complex. During the adsorption, due to the cationic nature of chitosan, negative charge residues compete with metal ion. In addition, differences in the efficiency of iron, magnesium and calcium ion adsorption may also result from their different valence that has an impact on the mechanism of chelate formation.

The sorption results clearly indicate a significance of the type of cellulose filler used for filling chitosan. It was shown that composites containing cellulose II with nanometric sizes (CHT/CNCII) adsorbed metal ion the best.

On the basis of the results obtained in this paper, it follows that the efficiency of metal ion adsorption in composites is a result of two factors: crystal structure of cellulose and particle size of cellulose fillers. The first factor to consider is polymorphism of cellulose. Quillin et al. (1993) maintain that the pyranose rings on the face of cellulose II are not aligned in a "flat" manner as is the case with cellulose I (Quillin et al. 1993). The importance of matching the cellulose crystal structure to other components (i.e. polymer) has been described in many papers (Wittman and Lotz 1990; Quillin et al. 1993; Felix and Gatenholm 1994; Son et al. 2000; Borysiak 2012, 2013b). This aspect plays also a decisive role in the nucleation process. Therefore, it can be assumed that parameters of crystal lattice of cellulose II correspond better with size of metal ion, thus increasing interactions and consequently enhancing sorption efficiency. However, in this research high ion adsorption was obtained only when nanometric cellulose II was used. Composites with micrometric cellulose II were not so effective, which suggest the presence of some synergy. High efficiency of calcium, magnesium, and iron ion adsorption can be obtained using chitosan composites containing both, filler with polymorphic form of cellulose II and its nanometer fraction. The presence of only cellulose nanometric filler (CNC I) did not guarantee high adsorption efficiency.

Wettability studies

Analysis of the results given in Table 3 shows that all of the tested samples were hydrophobic (contact angle > 90°). For almost all samples values of water CA were comparable and in range from 107.3° to 110.3°. Surprisingly, contact angle for CHT/CNC II sample was different, it was only 96°. Such situation was not observed for any other material. Figure 7 presents photos of samples during CA tests.

Chitosan itself is known to have low interaction with water. This is due to protonated amine groups (NH3+) disposed in chitosan backbone that appear while dissolution in acid solution (formation of cationic polymer). Migration of positive charges to sample surface results in weakening its adhesion with polar molecules of water (Mathur and Narang 1990).

In this study four different cellulose types were used as fillers for chitosan. However, when compared to pristine chitosan, only in case of one material its hydrophobicity was reduced. It is clear that CNC II filler was responsible for decrease of the contact angle value. The reasons for this phenomenon are complex and require consideration of two main factors: polymorphic form and size of filler.

Firstly, each cellulose polymorph has some unique properties that result from different supermolecular structure of the material. Cellulose II, called regenerated cellulose too, is less crystalline and has bigger size of elementary cell than cellulose I. Moreover, structure of cellulose II is looser and less packed than in native cellulose. It is a high affinity between molecules of water and polar groups of cellulose that causes films of regenerated cellulose to be among the most hydrophilic polymeric films (Lindman et al. 2017). Secondly, as follows the analysis of DLS results, particles of CNC II were definitely smaller (50.8–142 nm) than particles of C II (~ 40 µm) or even CNC I (78.8–4800 nm). The reduction in particle size was also associated with an increase in the amount of free -OH groups.

The results of wettability tests correlate well with adsorption studies. CHT/ CNC II composites were characterized with the highest sorption capability and the highest hydrophilicity. In this system, the metal ion found in the solution could much easier move to the interior of the bulk, where they could be coordinated by the functional groups of chitosan and thus adsorbed.

Tensile properties of composites

Tensile tests were performed to calculate Young’s modulus (YM), tensile strength (TS), and elongation at break (EB) parameters. The obtained data are presented in Table 4.

Introduction of each filler into polymer matrix resulted in increase of YM parameter. However, the highest value of the Young's modulus (2.52 GPa) was noted for CHT/CNC I composite and it was over ten times higher than for unfilled chitosan (0.24 GPa).

It can be also seen that polymorphic form of filler used had an influence on YM—higher values of this parameter were observed for composites with CNC I and C I fillers than in case of CNC II and C II. Surprisingly, it is not possible to unambiguously determine the influence of the size of the particles used. In case of native celluloses (C I and CNC I) higher values of YM were obtained if nanometric filler was used and for mercerized fillers (C II and CNC II) this trend was reversed.

Tensile strength for all composites was higher than for chitosan. Films with CNC I were characterized with definitely the highest TS, almost 75 MPa while chitosan reached only 24.9 MPa. This parameter was affected not only by polymorphic form of filler but also its size. It is evident that higher values were achieved when native cellulose was used. It also noticeable that composites with nanometric fillers exhibited higher tensile strength than films with micrometric celluloses. It is believed that the increase of particle size of reinforcement causes an enhanced debonding of the filler from polymer matrix. During dynamic loading of composites with large diameter particles the filler is separated from the matrix, which results in formation of free spaces. This phenomenon was not observed for composites with small filler particles.

As expected, introduction of cellulosic fillers into chitosan matrix resulted in sharp decrease of elongation at break. Interestingly, EB for composite with CNC I was found to be 50.4%, while for chitosan it was 42.2%. Achieving such high elasticity value for composite is extremely important because in most cases introduction of even a small amount of filler into polymer matrix causes EB parameter to drop. This is due to the high stiffness of cellulosic fillers that limit the elasticity of the material (Samir et al. 2004; Dai et al. 2015; Hosseini et al. 2015).

In view of above it is obvious that the tensile properties of composites depended strongly on the polymorphic variety and size of cellulosic filler used.

Composites with cellulose II are often characterized by lower values of tested parameters than materials with native cellulose, what is in agreement with other studies. Tests carried out on composites with wood proved that alkalization of wood was responsible for the reduction of mechanical properties (Marcovich et al. 2001). Other researchers also did not confirm the positive effect of mercerization on the macroscopic properties of composites (Ichazo et al. 2001; Pimenta et al. 2008; Borysiak 2013b; Borysiak and Grząbka-Zasadzińska 2016; Grząbka-Zasadzińska et al. 2018).

In general, it can be seen that composites with nanometric filler were characterized by higher mechanical parameters than micrometric composites (except for YM for mercerized fillers). That is due to higher effectiveness of stress transfer between matrix and nanometric filler (Fu et al. 2008). It is also in line with other researches showing that modulus of composites increases as the particle size decreases (Grząbka-Zasadzińska et al. 2019).

However, since particles of CNC II were found to be smaller than particles of CNC I one could expect that CHT/CNC II composites would exhibit better mechanical properties than CHT/CNC I. In fact, it is more complicated as two factors have to be taken into account: (1) negative effect of mercerization mentioned above, (2) agglomeration of nanometric fillers. As we showed in our previous work (Grząbka-Zasadzińska et al. 2019) characteristic feature of samples containing significant amounts of nanometric size particles, up to 220 nm, was their tendency to form micrometric agglomerates.

Conclusions

In this work, we analyzed the influence of supermolecular structure and dispersive properties of cellulose on the effectiveness of the metal ion adsorption in chitosan composites. It was shown that after mercerization CNC II had a particle size in the range of 50–120 nm, while starting CNC I had not only nanometric (80–120 nm) but also micrometric fraction (ca. 3–4 µm). Composites of chitosan and various types of cellulosic fillers were subjected to adsorption tests in aqueous solutions of following metal ion: Ca(II), Mg(II), and Fe(III).

Results of FAAS and FTIR tests showed some interesting, unreported relationship between the structure of the filler and effectiveness of the sorption process. It was found that the efficiency of metal ion sorption depends on two parameters—polymorphic form and size of the filler. The highest efficiency of adsorption (for all metal ion) was noted when filler with nanometric size of particles and supermolecular structure characteristic for cellulose II was used. Micrometric cellulose II did not guarantee such high efficiency.

In addition, it is worth noting, that composites with nanometric cellulose with polymorphic form of cellulose I, did not exhibit high adsorption efficiency. This results from ion of metal matching the dimensions of crystal lattice of cellulose. Nonetheless, the mechanism of this adsorption process is still not fully examined. Therefore, we plan to carry out further analysis using XPS method or desorption tests that could provide more insight into mechanism of sorption of metal ion on such biocomposites.

Contact angle studies have shown that composites with nanometric cellulose II had higher wettability of the surface. It ensures greater hydrophilicity and, consequently, affinity to aqueous metal ion solutions. From an application point of view, it is important that all chitosan composites were characterized by higher strength than the chitosan matrix.

Data availability

Data available within the article or its supplementary materials.

Code availability

Non applicable.

References

Abollino O, Aceto M, Malandrino M, Sarzanini C, Mentasti E (2003) Adsorption of heavy metals on Na-montmorillonite. Effect of pH and organic substances. Water Res 37:1619–1627. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1354(02)00524-9

Alade AO, Amuda OS, Ibrahim AO (2012) Isothermal studies of adsorption of acenaphthene from aqueous solution onto activated carbon produced from rice (Oryza sativa) husk. Desal Water Treat 46:87–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443994.2012.677514

Allouche FN, Guibal E, Mameri N (2014) Preparation of a new chitosan-based material and its application for mercury sorption. Colloids Surf A 446:224–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2014.01.025

Al-Wakeel KZ, Abd El-Monem H, Khalil MMH (2015) Removal of divalent manganese from aqueous solution using glycine modified chitosan resin. J Environ Chem Eng 3:179–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2014.11.022

Aydin YA, Aksoy ND (2009) Adsorption of chromium on chitosan: optimization, kinetics and thermodynamics. Chem Eng 151:188–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2009.02.010

Bhatnagar A, Sillanpaa M (2009) Applications of chitin- and chitosan-derivatives for the detoxification of water and wastewater—a short review. Adv Colloid Interface 152:26–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cis.2009.09.003

Bhattacharyya KG, Gupta SS (2008) Adsorption of a few heavy metals on natural and modified kaolinite and montmorilonite: a review. Adv Collioid Interface Sci 140:114–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cis.2007.12.008

Boamah PO, Huang Y, Hua M, Zhang Q, Wu J, Onumah J, Sam-Amoah LK, Boamah PO (2015) Sorption of heavy metal ion onto carboxylate chitosan derivatives—a mini-review. Ecotox Environ Safe 116:113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.01.012

Borysiak S (2012) Influence of wood mercerization on the crystallisation of polypropylene in wood/PP composites. J Therm Anal Calorim 109:595–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-012-2221-x

Borysiak S (2013a) Fundamental studies on lignocellulose/polypropylene composites: effects of wood treatment on the transcrystalline morphology and mechanical properties. J Appl Polym Sci 127:1309–1322. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.37651

Borysiak S (2013b) Influence of cellulose polymorphs on the polypropylene crystallization. J Therm Anal Calorim 113:281–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-013-3109-0

Borysiak S, Grząbka-Zasadzińska A (2016) Influence of the polymorphism of cellulose on the formation of nanocrystals and their application in chitosan/nanocellulose composites. J Appl Polym Sci 133:42864. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.42864

Bosso S, Enzweiler J (2002) Evaluation of heavy metal removal from aqueous solutions onto scolecite. Water Res 36:4795–4800. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1354(02)00208-7

Cahyaningrum SE, Herdyastuti N (2011) Soption of Mg(II) and Ca(II) metal ion on chitosan-alginate membrane. J Mat Sci Eng A 1:87–92

Cestari AR, Vieira EFS, dos Santos AGP, Mota JA, de Almeida VP (2004) Adsorption of anionic dyes on chitosan beads. 1. The influence of the chemical structures of dyes and temperature on the adsorption kinetics. J Colloid Interface Sci 280:380–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2004.08.007

Chatterjee S, Lee DS, Lee MW, Woo SH (2009) Nitrate removal from aqueous solutions by cross-linked chitosan beads conditioned with sodium bisulfate. J Hazard Mater 166:508–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.11.045

Chong KH, Volesky B (1995) Description of two-metal biosorption equilibria by Langmuir-type models. Biotechnol Bioeng 47:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.260470406

Cirini G, Badot PM (2008) Application of chitosan, a natural aminopolysaccharide for dye removal from aqueous solutions by adsorption processes using batch studies: a review of recent literature. Prog Polym Sci 33:399–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.11.001

Crini G (2005) Recent developments in polysaccharide–based materials used as adsorbents in wastewater treatment. Prog Polym Sci 30:38–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2004.11.002

Dai L, Qiu C, Xiong L, Sun Q (2015) Characterisation of corn starch-based films reinforced with taro starch nanoparticles. Food Chem 174:82–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.11.005

Felix JM, Gatenholm P (1994) Effect of transcrystalline morphology on interfacial adhesion in cellulose/polypropylene composites. J Mater Sci 29:3043–3049. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01117618

French AD (2014) Idealized powder diffraction patterns for cellulose polymorphs. Cellulose 21(2):885–896. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-013-0030-4

Fu SY, Feng XQ, Lauke B, Mai YW (2008) Effects of particle size, particle/matrix interface adhesion and particle loading on mechanical properties of particulate–polymer composites. Compos B Eng 39:933–961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2008.01.002

Gedam AH, Narnaware P, Kinhikar V (2018) Blended composites of chitosan: adsorption profile for mitigation of toxic Pb (II) ion from water. Chitin-Chitosan-Myriad Funct Sci Technol 6:99–118

Ghaee A, Shariaty-Niassar AM, Barzin J, Matsuura T (2010) Effects of chitosan membrane morphology on copper ion adsorption. Chem Eng J 165:46–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2010.08.051

Ghoul M, Bacquet M, Morcellet M (2003) Uptake of heavy metals from synthetic aqueous solutions using modified PEI-silica gels. Water Res 37:729–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1354(02)00410-4

Grząbka-Zasadzińska A, Skrzypczak A, Borysiak S (2019) The influence of the cation type of ionic liquid on the production of nanocrystalline cellulose and mechanical properties of chitosan-based biocomposites. Cellulose 26:4827–4840. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-019-02412-1

Grząbka-Zasadzińska A, Smułek W, Kaczorek E, Borysiak S (2018) Chitosan biocomposites with enzymatically produced nanocrystalline cellulose. Polym Compos 39:448–456. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.24552

Guibal E (2004) Interactions of metal ion with chitosan-based sorbents: a review. Sep Purif Technol 38:43–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2003.10.004

Heidari A, Younesi H, Mehraban Z, Heikkinen H (2013) Selective adsorption of Pb(II), Cd(II), and Ni(II) ion from aqueous solution using chitosan–MAA nanoparticles. Int J Biol Macromol 61:251–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.06.032

Hindeleh AM, Johnson DJ (1971) The resolution of multipeak data in fibre science. J Phys D Appl Phys 4(2):259–263. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/4/2/311

Hosseini SF, Rezaei M, Zandi M, Farahmandghavi F (2015) Fabrication of bio-nanocomposite films based on fish gelatin reinforced with chitosan nanoparticles. Food Hydrocolloid 44:172–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2014.09.004

Hu Z, Yijiu LL, Ni Y (2003) Chromium adsorption on high-performance activated carbons from aqueous solutions. Sep Purif Technol 31:13–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1383-5866(02)00149-1

Ichazo MN, Albano C, González J, Perera R, Candal MV (2001) Polypropylene/wood flour composites: treatments and properties. Compos Struct 54(2–3):207–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0263-8223(01)00089-7

Jayakumar R, Prabaharan M, Reis R, Mano JF (2005) Graft copolymerized chitosan—present status and applications. Carbohydr Polym 62:142–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2005.07.017

Kalapathy U, Proctor A, Shultz J (2000) Production and properties of flexible sodium silicate films from rice hull ash silica. Bioresour Technol 72:99–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-8524(99)00112-1

Kalyani S, Veera MB, Siva KN, Krishnaiah A (2009) Competitive adsorption of Cu(II), Co(II) and Ni(II) from their binary and tertiary aqueous solutions using chitosan-coated perlite beads as biosorbent. J Hazard Mater 170:680–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.05.106

Kaveeshwar AR, Sanders M, Ponnusamy SS, Depan D, Subramaniam R (2017) Chitosan as a biosorbent for adsorption of iron (II) from fracking wastewater. Polym Adv Technol 29(2):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pat.4207

Kumar S, Krishnakumar B, Sobral Abilio JFN, Koh J (2019) Bio-based (chitosan/PVA/ZnO) nanocomposites film: Thermally stable and photoluminescence material for removal of organic dye. Carbohydr Polym 205:559–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.10.108

Kyzas GZ, Siafaka PI, Lambropoulou DA, Lazaridis NK, Bikiaris DN (2014) Poly(itaconic acid)-grafted chitosan adsorbents with different cross-linking for Pb(II) and Cd(II) uptake. Langmuir 30:120–131. https://doi.org/10.1021/la402778x

Leusch L, Holan ZR, Volesky B (1995) Biosorption of heavy metals (Cd, Cu, Ni, Pb, Zn) by chemically reinforced biomass of marine algae. J Chem Technol Biot 62:279–288. https://doi.org/10.1002/jctb.280620311

Li N, Bai R (2005) Copper adsorption on chitosan-cellulose hydrogel beads: behaviors and mechanism. Sep Purif Technol 42:237–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2004.08.002

Lindman B, Medronho B, Alves L, Costa C, Edlund H, Norgren M (2017) The relevance of structural features of cellulose and its interactions to dissolution, regeneration, gelation and plasticization phenomena. Phys Chem Chem Phys 19(35):23704–23718. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7CP02409F

Loukidou MX, Matis KA, Zouboulis AJ, Liakopoulou-Kyriakidou M (2003) Removal of As(V) from wastewaters by chemically modified fungal biomass. Water Res 37:4544–4552. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1354(03)00415-9

Mahatmanti FW, Nuryono N, Narsito N (2016) Adsorption of Ca(II), Mg(II), Zn(II), and Cd(II) on chitosan membrane blended with rice hull ash silica and polyethylene glycol. Indones J Chem 16(1):45–52. https://doi.org/10.22146/ijc.21176

Mahvi A (2008) Application of agricultural fibers in pollution removal from aqueous solutions. Int J Environ Sci Technol 5:275–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03326022

Marcovich N, Aranguren M, Reboredo M (2001) Modified woodflour as thermoset fillers Part I. Effect of the chemical modification and percentage of filler on the mechanical properties. Polymer 42(2):815–825. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-3861(00)00286-X

Mathur NK, Narang CK (1990) Chitin and chitosan, versatile polysaccharides from marine animals. J Chem Educ 67:938–942. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed067p938

Milosavljevic NB, Ristić MD, Perić-Grujić AA, Filipović JM, Štrbac SB, Rakočević ZL, Kalagasidis Krušić MT (2011) Sorption of zinc by novel pH-sensitive hydrogels based on chitosan, itaconic acid and methacrylic acid. J Hazard Mater 192:846–854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.05.093

Minamisawaa H, Iwanami H, Arai N, Okutani T (1999) Adsorption behavior of cobalt(II) on chitosan and its determination by tungsten metal furnace atomic absorption spectrometry. Anal Chim Acta 378:279–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-2670(98)00641-2

Miretzky P, Cirelli AF (2009) Hg(II) removal from water by chitosan and chitosan derivatives: a review. J Hazard Mater 167:10–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.01.060

Negm NA, El Sheikh R, El-Farargy AF, Hassan HHH, Bekhit M (2015) Treatment of industrial wastewater containing copper and cobalt ion using modified chitosan. J Ind Eng Chem 21:526–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2014.03.015

Okoya A, Adeodun S (2017) Adsorption efficiency of chitosan-coated carbon for industrial effluent treatment. IJSER 8(5):1503–1509

Peijnenburg WJ, Baalousha M, Chen J, Chaudry Q, Von Der Kammer F, Kuhlbusch TA, Lead J, Nickel C, Quik JT, Renker M (2015) A review of the properties and processes determining the fate of engineered nanomaterials in the aquatic environment. Crit Rev Env Sci Tec 45:2084–2134. https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2015.1010430

Perelshtein I, Ruderman E, Perkas N, Tzanov T, Beddow J, Joyce E, Mason TJ, Blanes M, Molla K, Patlolla A, Frenkel AI, Gedanken A (2013) Chitosan and chitosan–ZnO-based complex nanoparticles: formation, characterization, and antibacterial activity. J Mater Chem B 1:1968–1976. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3TB00555K

Piątkowski M, Bogdał D, Radomski P, Jarosiński A (2010) Application of chemically modified chitosan in metal ion’ sorption. Czasopismo Techniczne 1:257–266

Pimenta MT, Carvalho AJ, Vilaseca F, Girones J, López JP, Mutjé P, Curvelo AAS (2008) Soda-treated sisal/polypropylene composites. J Polym Environ 16(1):35–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-008-0080-0

Qu RJ, Sun CM, Wang MH, Ji CN, Xu Q (2009) Adsorption of Au(II) from aqueous solutions using cotton fiber/chitosan composite adsorbents. Hydrometallurgy 100:65–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2009.10.008

Quillin DT, Caulfield DF, Koutsky JA (1993) Crystallinity in the polypropylene/cellulose system. I. Nucleation and crystalline morphology. J Appl Polym Sci 50:1187–1194. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.1993.070500709

Rabiej S (1991) A comparison of two X-ray diffraction procedures for crystallinity determination. Eur Polym J 27:947–954. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-3057(91)90038-P

Radomski P, Piątkowski M, Bogdał D, Jarosiński A (2014) Zastosowanie chitozanu oraz jego modyfikowanych pochodnych do usuwania śladowych ilości metali ciężkich ze ścieków przemysłowych. CHEMIK 68(1):39–48

Samir MASA, Alloin F, Sanchez JY, Dufresne A (2004) Cellulose nanocrystals reinforced poly(oxyethylene). Polymer 45(12):4149–4157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2004.03.094

Silva S, Braga C, Fook M, Raposo C, Carvalho L, Canedo E (2012) Application of Infrared Spectroscopy to analysis of chitosan/clay nanocomposites. In: Infrared spectroscopy—materials science, engineering and technology. ISBN: 978-953-51-0537-4. InTech. https://doi.org/10.5772/35522

Son SJ, Lee YM, Im SS (2000) Transcrystalline morphology and mechanical properties in polypropylene composites containing cellulose treated with sodium hydroxide and cellulase. J Mater Sci 35:5767–5778. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004827128747

Soundarrajan M, Gomathi T, Sudha PN (2013) Understanding the adsorption efficiency of chitosan coated carbon on heavy metal removal. IJSRP 3(1):1–10

Sun XQ, Peng B, Jing Y, Chen J, Li DQ (2009) Chitosan(chitin)/cellulose composite biosorbents prepared using ionic liquid for heavy metal ion adsorption. AIChE J 55:2062–2069. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.11797

Urbina L, Guaresti O, Requies J, Gabilondo N, Eceiza A, Corcuera MA, Retegi A (2018) Design of reusable novel membranes based on bacterial cellulose and chitosan for the filtration of copper in wastewater. Carbohyd Polym 193:362–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.007

Vakili M, Rafatullah M, Salamatinia B, Abdullah AZ, Ibrahim MH, Tan KB, Gholami Z, Amouzgar P (2014) Application of chitosan and its derivatives as adsorbents for dye removal from water and wastewater: a review. Carbohyd Polym 113:115–130

Varma AJ, Deshpande SV, Kennedy JF (2004) Metal complexation by chitosan and its derivatives: a review. Carbohydr Polym 55:777–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2003.08.005

Vijaya Y, Popuri SR, Boddu VB, Krishnaiah A (2008) Modified chitosan and calcium alginate biopolymer sorbents for removal of nickel (II) through adsorption. Carbohyd Polym 72:261–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2007.08.010

Vinodhini PA, Sangeetha K, Gomathi T, Sudha PN, Venkatesan J, Anil S (2017) FTIR, XRD and DSC studies of nanochitosan, cellulose acetate and polyethylene glycol blend ultrafiltration membranes. Int J Biolog Macromol 104:1721–1729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.03.122

Wang L, Wang A (2007) Adsorption characteristics of Congo Red onto the chitosan/montmorillonite nanocomposite. J Hazard Mater 147:979–985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.01.145

Wittman JC, Lotz B (1990) Epitaxial crystallization of polymers on organic and polymeric substrates. Prog Polym Sci 15:909–948. https://doi.org/10.1016/0079-6700(90)90025-V

Wu F, Tseng R, Juang R (2010) A review and experimental verification of using chitosan and its derivatives as adsorbents for selected heavy metals. J Environ Manag 91:798–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.10.018

Yang Z, Yuan Y (2001) Studies on the synthesis and properties of hydroxyl azacrown ether-grafted chitosan. J Appl Polym Sci 82:1838–1843. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.2026

Yue Y, Han G, Wu Q (2013) Transitional properties of cotton fibers from cellulose I to cellulose II structure. BioRes 8(4):6460–6471. https://doi.org/10.15376/biores.8.4.6460-6471

Zeng M, Fang Z (2004) Preparation of sub-micrometer porous membrane from chitosan/polyethylene glycol semi-IPN. J Membr Sci 245:95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2004.08.004

Zhang GY, Qu RJ, Sun CM, Ji CN, Chen H, Wang CH (2008) Adsorption for metal ion of chitosan coated cotton fiber. J Appl Polym Sci 110:2321–2327. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.27515

Zhang L, Zeng Y, Cheng Z (2016) Removal of heavy metal ion using chitosan and modified chitosan: a review. J Mol Liq 214:175–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2015.12.013

Zhang LM, Chen DQ (2002) An investigation of adsorption of lead(II) and copper(II) ion by water-insoluble starch graft copolymers. Colloids Surface A 205:231–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-7757(02)00039-0

Zhao J, Zhu YJ, Wu J, Zheng JQ, Zhao XY, Lu BQ, Chen F (2014) Chitosan-coated mesoporous microspheres of calcium silicate hydrate: environmentally friendly synthesis and application as a highly efficient adsorbent for heavy metal ion. J Colloid Interf Sci 418(27):208–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2013.12.016

Zhou L, Liu J, Liu Z (2009) Adsorption of platinum (IV) and palladium (II) from aqueous solutions by thiourea-modified chitosan microspheres. J Hazard Mater 172:439–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.07.030

Zhu HY, Jiang R, Xiao L (2010) Adsorption of an anionic dye by chitosan/kaolin/γ-Fe2O3 composites. Appl Clay Sci 48:522–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2010.02.003

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Polish Ministry of Education and Science.

Funding

This work was supported by the Polish Ministry of Education and Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

No Human Participants and/or Animals were involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grząbka-Zasadzińska, A., Ratajczak, I., Król, K. et al. The influence of crystalline structure of cellulose in chitosan-based biocomposites on removal of Ca(II), Mg(II), Fe(III) ion in aqueous solutions. Cellulose 28, 5745–5759 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-021-03899-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-021-03899-3