Abstract

Molecular interactions governing the recently reported CO2/CO32− chemistry of cellulose/NaOH(aq) solutions are investigated using a cellulose analogue methyl-β-D-glucopyranoside in NaOH(aq) solutions under conditions feasible with cellulose dissolution. 1H, 13C and steady-state heteronuclear Overhauser effect NMR spectroscopy complemented by pH measurements reveal carbohydrate–CO32− interactions as an important component of this chemistry. However, depending on in which order carbohydrate and CO32− are brought together in NaOH(aq) this interaction is different with different implications on stability of the CO32− in the solution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Elucidating fundamental interactions of the attractive cellulose/NaOH(aq) solutions is a pre-requisite for rational development of these systems towards a new sustainable processing technology. Yet, after more than a century of scientific and industrial interest, cellulose/NaOH(aq) interactions still pose challenges on mechanistic comprehension, particularly intriguing being the still unresolved instability of the solutions manifested as a remarkably strong tendency for cellulose–cellulose associations. Over the years repeated efforts have been made to elucidate the stabilising interactions and structure of this system pointing out eutectic sodium hydroxide hydrates as the key solubilising species (Roy et al. 2001; Egal et al. 2007), along with deprotonation of dissolved cellulose (Bialik et al. 2016). Interestingly, despite the inherent affinity of alkaline solutions for CO2(g) (due to low temperature and high alkalinity) influence of CO2(g) on the molecular interactions in this system has never been considered. Recently our group investigated an overlooked incorporation of CO2(g) in these solutions going through a reaction with cellulose alkoxides and the formation of a transient cellulose carbonate readily hydrolysed to CO32− (Gunnarsson et al. 2017). Similar chemistry had previously been observed in alkaline alcohol solutions (Faurholt 1927; Song and Rochelle 2017). Studies of a model compound methyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (α-MeO-Glcp) enabling investigation by NMR spectroscopy, established a significant incorporation of CO32− through this route as it is kinetically favored over the well-known conversion of CO2 to CO32− by OH− due to a higher affinity of CO2 for carbohydrate alkoxides (Chiang et al. 2017; Song and Rochelle 2017). The conversion of CO2(g) to CO32−(aq) in NaOH(aq) was more than doubled in the presence of a α-MeO-Glcp (Gunnarsson et al. 2018). Surprisingly, this excess incorporation of CO32− was not accompanied with any additional pH decrement and indicated a strong impact on the tendency of cellulose chains to re-associate. Applied to cellulose solutions, this new knowledge will add to comprehensive understanding of the delicate cellulose–NaOH(aq) interplay along with the prospect of developing new means of functionalising and assembling cellulose structures from aqueous alkaline solutions. As such, this newly found dimension calls for further investigations of the CO2–cellulose/NaOH(aq) chemistry in terms of structural requirements on the carbohydrate, dissolution conditions, etc., where conditions relevant for cellulose dissolution are of particular interest. With the narrow range of conditions favouring dissolution of cellulose in mind, we here turn our attention to a model system feasible with these very conditions, including the use of a more relevant low molecular analogue, β-MeO-Glcp (Fig. 1). Relying on a detailed NMR analysis of chemical shifts, coupling constants and interactions via the heteronuclear Overhauser effect (HOE), we further investigate the fundamentals of the CO2(g) capturing chemistry under conditions applicable to cellulose solutions (in terms of temperature and NaOH(aq) concentration). A complementary analysis of accompanying pH changes provides additional insight in interactions affecting the NMR signature. While aiming at general understanding of this chemistry, the formation and faith of the main reaction product, CO32−(aq), is in focus.

Experimental

Materials and sample preparation

β-MeO-Glcp (< 99%), NaOH (< 98%), NaCl (99.5%), D2O (99.9%) and Na213CO2 (99 atom% 13C) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and used as received. Microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) Avicel PH-101, with a degree of polymerisation of 260, was purchased from FMC BioPolymer and used without further treatment.

Solutions for characterisation of the chemical shift values and quantification of captured CO2 were prepared by dissolving NaCl (2.0 or 3.0 M) or NaOH (2.0 or 3.0 M) in D2O. The solutions were then cooled down to −5 °C. The cool solutions were then added to pre-weighed β-MeO-Glcp (0.4 M), let to dissolve and stored at +5 °C. CO2(g) was added for 120 s to the solutions, pre or post-dissolution of β-MeO-Glcp, by immersing a syringe into the solutions. The syringe was connected to a tube containing CO2(g), mounted with a regulator set to approximately 4 ml/min. A solution for the steady-state HOE experiment was prepared by dissolving NaOH (2.0 M) and Na213 CO2 (1.0 M) in D2O at room temperature and added to pre-weighed MCC (0.4 M) in a vial. The suspension was then vigorously shaken to obtain a homogeneous sample, transferred using a pipette to an NMR tube and put in a freezer at −20 °C. The frozen sample was then placed inside the magnet and thawed at +5 °C, which dissolves cellulose and gives a stable solution to perform measurements on.

The pH measurements were carried out by pre-cooling NaOH(aq) with a concentration of 0.5 M at +10 °C. The pH was then measured pre or post-dissolution of β-MeO-Glcp (0.4 M) with addition of CO2(g) for 120 s pre or post-dissolution of the β-MeO-Glcp according to the method above. The pH was measured using a HACH HQ430D Multimeter with an Intellical PHC705A1 pH probe.

Characterisation

All NMR experiments were run on an 800 MHz magnet equipped with a Bruker Avance HDIII console and a TXO cryoprobe. 1H NMR spectra were recorded with the relaxation delay and number of scans set to 5 s and 8, respectively.

13C NMR spectra were recorded with a low angle radio frequency pulse to minimise relaxation-weighting using a single pulse experiment with 1H decoupling during acquisition. Hence, the repetition delay and number of scans was set to 33.0 s and 64, respectively, for monitoring the amount of dissolved CO2 while a repetition delay of 5 s was used for the observation of chemical shift differences. A capillary containing D2O with 3-(trimethylsilyl)-1-propanesulfonic acid sodium salt (DSS) was placed inside the tube as internal reference.

A steady-state heteronuclear Overhauser effect (HOE) measurement was performed to observe if there is any specific interaction between the CO32−and MCC. A 1D HOE experiment was recorded using 13C labelled Na213 CO3 to transfer the magnetisation between the 13C to the 1H, which can be observed since all bonded H atoms of MCC are visible in a 1H NMR spectrum. A low power 90° radio frequency (RF) pulse was applied on resonance of the carbonate peak 100 times with a delay of 10 ms in between to saturate the carbonate signal. After a delay of 13 s, the 1H signal was excited with a strong short 90° RF pulse and recorded. The difference between two experiments, one with and one without saturation, indicates which sites interact with the carbonate. 1600 accumulations of the signal were recorded for both experiments at +5 °C.

Results and discussion

β-MeO-Glcp mediated uptake of CO2(g)

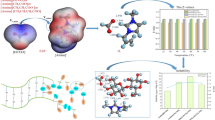

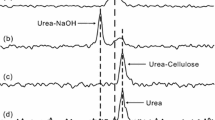

As expected β-MeO-Glcp (3.0 M samples) showed a significant difference in chemical shifts compared to the previously investigated α-anomer, proving the difference in orientation of the methyl group at position C1 to largely influence the chemical environment of the surrounding carbons in the ring (see Supplementary Information Fig. 1a) (Lemieux 1971) and probably also the interaction with CO2(g). Moreover, the alkali concentration appeared to change the NMR signature of the carbohydrate, as comparison between the 2.0 and 3.0 M systems showed that only some of the carbons of the β-MeOH-Glcp experienced a change in chemical shift upon increase in the alkali concentration (see Supplementary Information Fig. 1b). This was probably due to a difference in the hydroxyl exchange rate owing to the difference in pH, which consequently could affect the CO2(g) uptake of the system. With this in mind, further exploration of the CO2(g) uptake was performed on the 2.0 M NaOH(aq) solutions (comparable to cellulose solution conditions) and in the presence of the β-MeO-Glcp substrate. The uptake of CO2(g) by 2.0 M β-MeO-Glcp/NaOH(aq) estimated from the CO32− integral by quantitative 13C NMR is shown in Fig. 2.

In our previous study the presence of α-MeO-Glcp in 3.0 M NaOH(aq) was found to increase the uptake of CO2(g) regardless of whether it was added prior or after addition of the carbohydrate (Gunnarsson et al. 2018), i.e. whether by stabilising the already dissolved CO32−(aq) or by mediating incorporation of CO2(g) through organic carbonate and facilitate stabilisation of the subsequently formed CO32−. Interestingly, the β-anomer in 2.0 M, studied here, showed this effect only when dissolved in the NaOH(aq) prior to addition of CO2(g). When added to the solution already containing CO32−(aq), the stabilisation effect seemed to be reversed and a reduced CO32−(aq) peak could be measured (Fig. 2). This intriguing reduction of the CO32−(aq) peak cannot be attributed to a conversion of CO32−(aq) to CO2(g) at this high alkalinity, but could possibly indicate precipitation of the CO32− from the solution. In support to the precipitation possibility, the overall uptake of CO2(g) measured in this study (2.0 M NaOH(aq)) was higher compared to the previously studied 3.0 M NaOH(aq) (0.35 mol CO32−compared to 0.08 mol CO32− per mol carbohydrate-free NaOH(aq)), possibly due to a difference in viscosity reducing the reaction rate in the 3.0 M NaOH(aq). Attempts were made to confirm precipitation of Na2CO3(s) by light scattering, but no conclusive results could be obtained. Nevertheless, adding the carbohydrate to a solution containing already dissolved CO32−(aq) contributes poorly to stabilisation of this ion, unless present in low concentrations.

On the other hand, incorporation of CO32−(aq) introduced to a NaOH(aq) solution already containing dissolved carbohydrate (post-carbohydrate addition of CO2(g)) is remarkably facilitated by the presence of β-MeO-Glcp, just as in the case of the α-anomer (Gunnarsson et al. 2018). The uptake of CO2(g) increased, namely, from 0.35 mol CO32−/mol NaOH to 0.55 mol CO32−/mol NaOH when β-MeO-Glcp was present before the addition of CO2(g). The significantly higher content of CO32−(aq) in the solution does not, in this case, lead to precipitation but seems to be remarkably stabilised by the β-MeO-Glcp present in the solution prior to formation of CO32−(aq).

Notably, the total increase in the CO2(g) uptake due to presence of carbohydrate was equal in both the 3.0 M and 2.0 M system (0.2 mol/mol NaOH) which points out the critical role of the carbohydrate for the CO2(g) uptake.

The intriguing question is why stabilisation of the dissolved CO32− ions is more efficient when CO2(g) is introduced to the solution containing already dissolved carbohydrate (whether α or ß anomer)? Are there CO32− ions experiencing two different chemical surroundings: the CO32− ions hydrated prior to the addition of carbohydrate and those (significantly more abundant), formed and solvatised in the presence of carbohydrate? Here, the amphiphilic nature of the CO32− ion and its ability to form strong structures with water should be considered (Winkworth-Smith et al. 2016; Yadav and Chandra 2018).

In an effort to address these questions, changes in chemical shifts and coupling constants of the carbohydrate and chemical shifts of CO32− when added to the NaOH(aq) solution in different order were studied.

NMR signature of the CO2(g) uptake

In line with previous observations, the 13C chemical shifts for the β-MeO-Glcp in NaOH(aq) moved towards higher values compared to the reference solution in NaCl(aq). Given the high pH of these solutions (theoretical pH at 25 °C is 14.3), this change indicates deprotonation of one or several of the hydroxyl groups on the β-MeO-Glcp since the carbons exhibit an electron-deshielding effect (Isogai et al. 1987). The change observed in 1H NMR chemical shifts (i.e. move towards lower chemical shift values due to the shielding effect) also concurs with the previously observed deprotonation signature. The largest change in chemical shift, in both the 13C and 1H NMR measurements, was observed for the C3 and H3 position in the β-MeO-Glcp (see Supplementary information). Given a relatively low acidity of the hydroxyl in position 3, it is not likely that the large change can be attributed to deprotonation at this position but rather to a change in the surrounding environment induced by the deprotonation of one of the neighboring hydroxyl groups in position 2 and 4, a hypothesis not yet thoroughly investigated.

Addition of CO2(g) to the NaOH(aq) system prior or after the dissolution of β-MeO-Glcp, displaced the 13C NMR peaks to lower chemical shifts, with the accomplished displacement being significantly larger when adding CO2(g) after the dissolution of the carbohydrate (post-carbohydrate addition). In the case of post-carbohydrate addition of CO2(g), a significantly higher amount of CO32−(aq) is produced, which probably is partly responsible for the observed larger change in chemical shift. However, it should be kept in mind that CO32−(aq) incorporation in this case (post-carbohydrate addition) occurs through a different route—a reaction between the deprotonated carbohydrate and CO2(aq) via formation of a carbohydrate carbonate intermediate and might, as such, result in CO32− with different solvatisation and interactions additionally affecting the chemical shifts of the carbohydrate (Fig. 3) (Gunnarsson et al. 2018). This assumption is consistent with the change in chemical shifts between the pre- or post-carbohydrate addition of CO2(g) being different for different C atoms. This indicates different carbohydrate–CO32− interactions in the two cases, whether due to changed actual carbohydrate–CO32− association or changed structuring of the solvatising water around these. The largest difference could be observed for position C3 and C5.

The estimated spin–spin couplings (see Supplementary information) agreed well with the other reports in the literature (Stenutz et al. 2002). Analysis of the spin–spin couplings informs on molecular orientation between the adjacent protons and, thus, conformational changes in these two cases concurred with this observation: a change in the 3JHH couplings of the β-MeO-Glcp could only be observed upon addition of CO2(g) to the NaOH(aq) after dissolution of carbohydrate. A difference by 1 Hz could be observed for one of the couplings on the H6R proton, which by applying the Karplus equation indicates a change to a larger population with the hydroxymethyl group adopting the gauche–trans (gt) orientation (Stenutz et al. 2002; Angles d’Ortoli et al. 2015). In native cellulose crystals, the hydroxymethyl group is, namely, predominantly oriented away from the ring oxygen (a 180° torsional angle O5–C5–C6–O6, trans) and close to the C4 (a 60° torsional angle C4–C5–C6–O6, gauche), referred to as a trans–gauche (tg) conformation. Upon dissolution, the other two available populations (gauche–gauche (gg) with the both torsional angles of 60° and gauche–trans with the torsional angle O5–C5–C6–O6 being 60° and C4–C5–C6–O6 adapting 180°) will significantly increase. This proton couples both to another proton (H6S) on the same carbon (C6) and to the proton (H5) on the neighboring carbon (C5). The change for only one of the protons on the C6 carbon makes it reasonable to argue that it is the coupling to H5 that is affected by the post-carbohydrate addition of CO2(g). Unfortunately, the equal change for H5 could not be observed due to overlap with H3. Interestingly, the same proton is affected upon dissolution of the β-MeO-Glcp in NaOH(aq) (the only 3JHH changes observed when going from NaCl(aq) to NaOH(aq) solvent) due to the well-known conformation change of the primary hydroxyl from tg to gt in aqueous solutions (Horii et al. 1983; Bergenstråhle-Wohlert et al. 2016). Addition of CO2(g) prior to carbohydrate did not affect the 3JHH couplings. These findings further strengthen the indication of different carbohydrate–CO32−(aq) interactions in the case of CO2(g) introduction prior and after the carbohydrate.

Evaluation of the chemical shift of CO32−(aq) in the studied solutions harmonise to large extent with these findings (Table 1). The chemical shift of the CO32−(aq) in a carbohydrate-free NaOH(aq) and in the solutions where CO2(g) was added prior to carbohydrate were equal, namely 171.1 ppm. On the other hand, when CO2(g) was added after dissolution of carbohydrate, the chemical shift of the CO32−(aq) decreased to 169.2 ppm. As formation of HCO3−(aq) (and a fast exchange between the CO32−(aq) and HCO3−(aq) resulting in a peak at the average of the two species) can be excluded at this high pH, the reduction of the chemical shift of the CO32−(aq) implies formation of this ion in a different chemical environment. Possibly, the reaction between the deprotonated β-MeO-Glcp and the added CO2(g) going through formation of a transient carbohydrate carbonate (although not observed as a new intermediate peak) leads to β-MeO-Glcp–CO32− associations different from those established when CO32−(aq) is formed in a carbohydrate free NaOH (aq) prior to the carbohydrate addition.

Of course, having in mind the significantly larger CO2(g) uptake when added after the dissolution of the carbohydrate (Fig. 2), the observed alterations of the NMR signature of b-MeO-Glcp (chemical shifts and 3JHH) and CO32−(aq) (chemical shifts) could be partly attributed to partly attributed to a larger amount CO32−(aq) present in the system creating different surroundings. Still, as the change in chemical shift between the pre- and post-carbohydrate addition of CO2(g) varies for different C-atoms, there are likely other interaction differences than those originating merely from variations in the CO32−(aq) concentration. Our previous attempts on elucidating chemical shift variations as a function of increasing CO32−(aq) concentration indicated indeed different variation patterns for pre- and post-carbohydrate addition (Gunnarsson et al. 2018).

The obvious possibility of pH variations affecting deprotonation and, thus, giving rise to variations in ∆δ among the C-atoms could be excluded by establishing approximately equal final pH values for both cases (as will be seen further down).

An effort was made to distinguish between the different CO32−(aq) in the system by lowering the temperature in the NMR experiment since the chemical shift value is an average of the different chemical structures of a molecule in solution and a decrease in temperature will slow down the kinetics of the system and allow several species to be observed. Unfortunately, this approach could not be applied due to the fact that CO32−(aq) precipitates below 0 °C, which would affect the dynamics and change the properties of the system.

Comparison to changes in pH

Interactions of the system with CO2 should be closely related to pH, why pH changes—carrying additional information of the dynamics of the system—were monitored. Incorporation of CO32−(aq) is supposedly accompanied by a reduction of pH, even though the route going through formation of a carbohydrate carbonate was observed to consume relatively low amount of OH− leading to a comparably modest pH lowering (Table 2). The pH values measured for reference solutions and NaOH(aq) solutions with CO2 and β-MeO-Glcp added in different order are shown in Table 2, while the overall decrease in pH is shown in Table 3.

Deprotonation of β-MeO-Glcp could be observed as a reduction of pH upon dissolution in NaOH(aq). Interestingly, when CO32−(aq) is present in the system prior to carbohydrate dissolution (i.e. when CO2 is added prior to the dissolution of the β-MeO-Glcp) the deprotonation effect is even more pronounced, indicating that CO32−(aq) facilitates deprotonation of the β-MeO-Glcp (Fig. 4).

Just as shown in our previous study, in spite of higher incorporation of CO32− in the case of post-carbohydrate addition of CO2(g) almost equal final pH of the solutions (whether CO2(g) was added prior or after the carbohydrate) could be measured. This excludes the possibility of pH variations being responsible for the observed changes of the NMR peaks and once again points out displacement of chemical shifts as a strong indication of carbohydrate–CO32− interactions in the case of post-carbohydrate addition of CO2(g).

Taken together, our results strongly suggest a specific interaction between the CO32− formed through the carbohydrate carbonate chemistry upon post-carbohydrate addition, observed as changed NMR-signature of the carbohydrate (Δδ, 3JHH) and CO32−(aq) (decreased chemical shift), along with modest changes in pH accompanying this significant incorporation of CO32−. On the other hand, the CO32−(aq) present in the solution prior to carbohydrate addition seems to promote deprotonation of the added carbohydrate, while showing tendency itself to possibly precipitate upon carbohydrate addition. The question is whether this type of the CO32− also associates to carbohydrate. To address this question steady-state HOE experiments were employed.

Is there association between CO32− and cellulose?

The results obtained from both NMR and pH measurements all point towards an interaction between CO32− and β-MeO-Glcp when dissolved in NaOH(aq), particularly in the case of post-carbohydrate addition of CO2(g). Therefore, an attempt was made to probe whether there actually is an association between the CO32−(aq) introduced to the system prior to addition of carbohydrate (in this case microcrystalline cellulose, MCC) by measuring steady-state HOE on MCC dissolved in NaOH(aq) in the presence of 13CO32−. The concept of a steady-state HOE measurement is to saturate a specific site of a molecule and, use the magnetisation transfer via the Overhauser effect, to other nuclei to probe their proximity. Here, the 13CO32− was saturated while a 1H spectrum of dissolved MCC was recorded. Conventional 1D HOESY experiments that require strong heteronuclear dipolar couplings were also tested without success. If the 13CO32− is located sufficiently close to the MCC to allow for magnetisation transfer, it will be observed as a change in intensity of the measured proton peaks. Indeed, the intensity for all the MCC protons decreased by the saturation of the 13CO32− signal, which thereby proves an association between the 13CO32− and the MCC (Fig. 5). However, the decrease in intensity observed for all the protons indicates a non-specific association and a fast exchange between the 13CO32− and the MCC, which motivates further studies of this interaction.

Conclusions

The CO32−(aq) formed in NaOH(aq) solutions of a cellulose analogue β-MeO-Glcp, through incorporation of CO2(g) shows different interactions with the carbohydrate depending on when (relative to the carbohydrate) it is introduced. When present in the solution prior to addition of the carbohydrate it seems to be capable of facilitating deprotonation of the incoming carbohydrate. Even though HOESY measurements confirm a non-specific association between cellulose and CO32−(aq), this CO32−(aq) is likely poorly stabilised by the carbohydrate and prone to precipitate at higher concentrations. On the other hand, CO32− formed through addition of CO2(g) to a system containing already dissolved carbohydrate seems to be stabilised by the very presence of carbohydrate most likely promoted by a specific reaction with carbohydrate alkoxides accompanied by a conformational change of the primary hydroxyl group. In this case a significantly higher amount of CO32− is incorporated in the solutions through the previously described carbohydrate carbonate route responsible for modest OH− consumption and, thus, comparably modest pH change. The high amount of introduced CO32− along with its anticipated stabilising interaction with the carbohydrate is likely one of the main reasons behind the significant decrease of the chemical shifts (of both carbohydrate and CO32−) in the case of post-carbohydrate addition of CO2.

Still, one of the most intriguing questions remains to be further elucidated: why is the CO32−(aq) formed through the post-carbohydrate addition of CO2 stabilised in the β-MeO-Glcp/NaOH(aq) solution, while the CO32−(aq) formed by OH− reaction with CO2 prior to dissolution of β-MeO-Glcp is not?

References

Angles d’Ortoli T, Sjöberg NA, Vasiljeva P et al (2015) Temperature dependence of hydroxymethyl group rotamer populations in cellooligomers. J Phys Chem B 119:9559–9570. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b02866

Bergenstråhle-Wohlert M, Angles d’Ortoli T, Sjöberg NA et al (2016) On the anomalous temperature dependence of cellulose aqueous solubility. Cellulose 23:2375–2387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-016-0991-1

Bialik E, Stenqvist B, Fang Y et al (2016) Ionization of cellobiose in aqueous alkali and the mechanism of cellulose dissolution. J Phys Chem Lett 7:5044–5048. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b02346

Chiang C-Y, Lee D-W, Liu H-S (2017) Carbon dioxide capture by sodium hydroxide–glycerol aqueous solution in a rotating packed bed. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 72:29–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2017.01.023

Egal M, Budtova T, Navard P (2007) Structure of aqueous solutions of microcrystalline cellulose/sodium hydroxide below 0 C and the limit of cellulose dissolution. Biomacromol 8:2282–2287. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm0702399

Faurholt C (1927) Studies on monoalkyl carbonates. II. The formation of monoalkyl carbonic acids or their salts on dissolving carbon dioxide in aqueous solutions of alcohols of different degrees of acidity. Z Phys Chem B 126:85–104

Gunnarsson M, Theliander H, Hasani M (2017) Chemisorption of air CO2 on cellulose: an overlooked feature of the cellulose/NaOH(aq) dissolution system. Cellulose 24:2427–2436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-017-1288-8

Gunnarsson M, Bernin D, Åsa Östlund, Hasani M (2018) The CO2 capturing ability of cellulose dissolved in NaOH(aq) at low temperature. Green Chem 20:3279–3286. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8GC01092G

Horii F, Hirai A, Ryozo K (1983) Solid-state 13C-NMR study of conformations of oligosaccharides and cellulose. Polym Bull 10:357–361

Isogai A, Ishizu A, Nakano J (1987) Dissolution mechanism of cellulose in SO2–amine–dimethylsulfoxide. J Appl Polym Sci 33:1283–1290. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.1987.070330419

Lemieux RU (1971) Effects of unshared pairs of electrons and their solvation on conformational equilibria. Pure Appl Chem 25:527. https://doi.org/10.1351/pac197125030527

Roy C, Budtova T, Navard P, Bedue O (2001) Structure of cellulose–soda solutions at low temperatures. Biomacromol 2:687–693. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm010002r

Song D, Rochelle GT (2017) Reaction kinetics of carbon dioxide and hydroxide in aqueous glycerol. Chem Eng Sci 161:151–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2016.11.048

Stenutz R, Carmichael I, Widmalm G, Serianni AS (2002) Hydroxymethyl group conformation in saccharides: structural dependencies of 2JHH, 3JHH, and 1JCH spin–spin coupling constants. J Org Chem 67:949–958. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo010985i

Winkworth-Smith CG, MacNaughtan W, Foster TJ (2016) Polysaccharide structures and interactions in a lithium chloride/urea/water solvent. Carbohydr Polym 149:231–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.04.102

Yadav S, Chandra A (2018) Structural and dynamical nature of hydration shells of the carbonate ion in water: an ab initio molecular dynamics study. J Phys Chem B 122:1495–1504. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b11636

Acknowledgments

Open access funding provided by Chalmers University of Technology. This work has been carried out as a part of the framework of Avancell—Center for Fiber Engineering, which is a research collaboration between Södra Innovation and Chalmers University of Technology. The author thanks the Södra Skogsägarnas Foundation for Research, Development and Education for their financial support. The Swedish NMR Center is acknowledged for spectrometer time.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gunnarsson, M., Bernin, D. & Hasani, M. The CO2/CO32−chemistry of the NaOH(aq) model system applicable to cellulose solutions. Cellulose 27, 621–628 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-019-02782-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-019-02782-6