Abstract

Practicing newly acquired skills in different contexts is considered a crucial aspect of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for anxiety disorders (Peris et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 56:1043–1052, 2017; Stewart et al. Prof Psychol Res Pract 47:303–311, 2016). Learning to cope with feared stimuli in different situations allows for generalization of learned skills, and experiencing non-occurrence of the feared outcome helps in developing non-catastrophic associations that may enhance treatment outcomes (Bandarian-Balooch et al. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 47:138–144, 2015; Cammin-Nowak et al. J Clin Psychol 69:616–629, 2013; Kendall et al. Cogn Behav Pract 12:136–148, 2005; Tiwari et al. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 42:34–43, 2013). To optimize treatment outcome, homework is often integrated into CBT protocols for childhood anxiety disorders during and following treatment. Nevertheless, practicing at home can be challenging, with low motivation, lack of time, and insufficient self-guidance often listed as reasons for low adherence (Tang and Kreindler, JMIR Mental Health 4:e20, 2017). This conceptual review provides an overview of (1) how existing CBT childhood programs incorporate homework, and empirical evidence for the importance of homework practice, (2) evidence-based key elements of practice, and (3) how mHealth apps could potentially enhance practice at home, including an example of the development and application of such an app. This review therefore sets the stage for new directions in developing more effective and engaging CBT-based homework programs for childhood anxiety disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Experiencing fear or anxiety is part of development and is a normal response in threatening situations. However, when fear and/or anxiety is excessive, occurs in the absence of actual danger, and interferes with daily functioning, a child is likely to meet the criteria for an anxiety disorder (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). With a prevalence of 15–20%, anxiety disorders are among the most prevalent mental disorders that hinder children in their development (APA, 2013; Beesdo et al., 2009; Polanczyk et al., 2015). Children often meet criteria for more than one anxiety disorder at the same time and comorbidity with other disorders is high (Ollendick et al., 2008). Moreover, untreated childhood anxiety disorders are frequently associated with impairments in academic and social-emotional functioning and an increased risk of developing other psychopathology in adulthood (de Vries et al., 2019; Lieb et al., 2016; Rapee et al., 2009). The enormous impact of anxiety disorders on children’s development highlights the need for early and effective interventions for childhood anxiety disorders.

Over the past decades, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has received strong support and is considered the first-choice treatment for childhood anxiety disorders (Higa-McMillan et al., 2016; Warwick et al., 2017). CBT is inherently an integrative therapy (see Power, 2002) and therefore encompasses a broad range of treatment elements, such as exposure, cognitive restructuring, psychoeducation, parent involvement, relaxation, social skills training, mindfulness, and more, depending on the specific CBT program (e.g., Brave; Spence et al., 2006; Cool Kids; Rapee et al., 2006; Coping Cat; Kendall et al., 1990; One-Session Treatment; Öst & Ollendick, 2001). Even though CBT has been shown to be effective and the majority of children are free of their anxiety disorder(s) after treatment (Cartwright-Hatton et al., 2004), there is still room for improvement in treatment outcomes. Indeed, around 40% of youth receiving CBT are not free of their anxiety problems after treatment (James et al., 2013; Silverman et al., 2008; Warwick et al., 2017). In addition, a recent meta-analysis on relapse rates after CBT for youth anxiety showed an overall relapse rate of 10.5% across studies, and relapse rates did not differ between different primary anxiety disorder diagnoses (Levy et al., 2022). Thus, both long- and short-term treatment effectiveness could benefit from further refinement of treatment protocols.

During CBT, a significant focus is placed on extinction (or inhibitory learning), which refers to a learning process in which individuals develop a new, non-catastrophic association or representation in memory (e.g., ‘when I am confronted with a dog, nothing dangerous will happen’) that competes with the original catastrophic, fearful association (e.g., ‘when I am confronted with a dog, the dog will bite me’) (Craske et al., 2022). Considering that the old, fearful association is thought to still exist after creating the new, non-catastrophic association, there is a chance that the old association will be activated upon re-encountering the feared stimulus or situation in a new context (i.e., fear renewal; Craske et al., 2022). The chance of fear renewal can be minimized with practicing the newly learned skills in a broad range of contexts. This promotes generalization and reinforces the newly learned non-catastrophic association, thereby reducing the chance of relapse (Craske et al., 2014, 2022). The prescription and implementation of homework exercises is therefore considered crucial to learn CBT skills in different contexts and in real-life situations, outside the therapeutic context. In this manner, children learn that their feared outcome does not occur in a wide range of contexts. Indeed, many CBT programs incorporate home practice both during and after therapy in an effort to maintain treatment gains (Beck & Dozois, 2011; Öst & Ollendick, 2017; Tang & Kreindler, 2017).

One potential way to improve treatment outcome for childhood anxiety involves a renewed focus on the role of homework during and after treatment. While homework is considered an important element in most child CBT programs, few studies have specifically examined its effects on treatment outcomes, and the results are mixed (e.g., Arendt et al., 2016; Hughes & Kendall, 2007). Therefore, the overarching purpose of the current review is to provide an overview of the existing literature on homework in order to propose new directions for how homework could enhance treatment outcomes. More specifically, we focused on three aspects in our review: First, we provide a brief overview and examples of how treatment programs for childhood anxiety currently incorporate homework. Second, we describe the theoretical, evidence-based core elements that should be included in homework. Finally, we explore how digital health innovations, such as a smartphone application, could potentially facilitate the homework process. In this regard, we provide an example of the development of such an app.

Overview of How Homework is Incorporated in Current CBT Programs for Childhood Anxiety Disorders

Most homework practice in CBT programs for childhood anxiety disorders aligns with the scope and content of areas addressed during the sessions (see e.g., Power, 2002). Given CBT’s integrative nature, homework assignments therefore reflect the broad range of treatment elements, including, among others, exposure (e.g., practicing with exposure to a feared situation), cognitive restructuring (e.g., filling out cognitive restructuring exercises), and psychoeducation (e.g., reading materials on the rationale of CBT). Most often, this means that a child attends a session, discusses, or practices a specific topic together with the therapist, and then completes the associated homework assignments. Alternatively, the homework may involve preparation for an upcoming session or continued practice with previously learned skills.

The currently used childhood CBT programs are largely based on studies and programs originally developed for adults (e.g., Beck, 1976). One of the first studies reported on using behavioral techniques to overcome childhood anxiety was reported in the 1980s (King et al., 1988) and the first formalized CBT program for childhood anxiety disorders to also include homework assignments was published in 1990 (Kendall et al., 1990). Childhood anxiety CBT programs are most often generic in nature, meaning that they are not (anxiety) disorder specific. Examples of widely used generic child CBT programs for anxiety disorders are Coping Cat (Kendall & Hedtke, 2006a, 2006b), the Friends program (Barrett et al., 2000a, 2000b, 2000c), Cool Kids (Rapee et al., 2006), Think Good – Feel Good (Stallard, 2005), Discussing + Doing = Daring (DDD; Bögels, 2008), the BRAVE program (Spence et al., 2006), and the CHILLED program (Schniering & Rapee, 2020). There are also some programs designed for specific anxiety disorders, such as the One-Session Treatment (OST) for childhood specific phobias (Öst & Ollendick, 2001; based on Öst, 1989, 1997) and the Separation Anxiety Family Therapy, also known as the TAFF program, for childhood separation anxiety (Schneider et al., 2011).

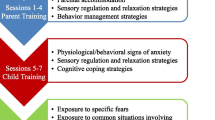

An example of one of the first generic programs where homework is integrated into the treatment protocol is Coping Cat (Kendall & Hedtke, 2006a, 2006b; Kendall et al., 1990). This program focusses on four major cognitive components: (1) recognizing anxious feelings and somatic reactions to anxiety, (2) identifying cognitions in anxiety-provoking situations, (3) developing a plan to help cope with the situation, and (4) evaluating the success of the coping strategies and self-reinforcement. Additionally, strategies such as modeling, in vivo exposure, role play, relaxation training, psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, and reinforced practice are used. Following each weekly session, children are assigned homework tasks aligned with the content of that specific session (Hudson & Kendall, 2002). Homework is reviewed at the beginning of each succeeding session and compliance is rewarded. The full CBT program aims to teach children several skills, and the skills that are addressed during the session are also part of the weekly homework for the child. For example, the first skill that is taught in Coping Cat is affect recognition. As a homework task, children are asked to write about a situation in which they felt scared or nervous and a situation in which they felt relaxed (Kendall & Hedke, 2006a, 2006b).

Since the first CBT programs for childhood anxiety disorders were developed, several adaptations have been made. First, some programs that were only available face to face in the earlier years were later adapted to be followed at home, guided by a therapist. Often first as CD-ROM versions and later as full online programs, such as the computer assisted version of Coping Cat named Camp Cope a Lot (Khanna & Kendall, 2008), the Cool Kids program (Chatterton et al., 2019; Lyneham & Rapee, 2006; McLellan et al., 2015), the CHILLED plus program (online version of the Chilled program; Schniering et al., 2022), and the BRAVE online program (March et al., 2008, 2018; Spence et al., 2011). Several studies showed that these online programs were effective in reducing childhood anxiety (e.g., Khana & Kendall, 2010; Rapee et al., 2006; Stasiak et al., 2016; Wuthrich et al., 2012), and the BRAVE online program was also found to be as effective as the face-to-face program (Spence et al., 2011). To further elaborate on the content of one of these online CBT programs, we will have a closer look at BRAVE online. This program comprises 10 weekly child/adolescent sessions (ca. 60 min per session). The program is followed by two booster sessions, 1 and 3 months after completion of the initial program. During the 10 weekly online sessions, children and adolescents learn different anxiety management strategies together with their family from home, including recognition of the physiological symptoms of anxiety, relaxation strategies (progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, and deep breathing), cognitive strategies of coping self-talk and cognitive restructuring, graded exposure, problem-solving techniques, and self-reinforcement of “brave” behavior. Each session starts with a summary and quiz about the previous session and ends with a summary and quiz about the current session. Homework exercises are in line with the content of the sessions and are completed between sessions (e.g., a fear hierarchy or exposure task), and therapists provide feedback on the exercises (Spence et al., 2008).

A second adaption to the CBT programs is that some authors created modular versions of their integrated protocols. If the therapist chooses to work with a modular version of the protocol, this usually means that the child only completes the homework that belongs to the specific modules that are used. This means that not all children do the same homework assignments but may skip part of the homework or repeat some of the homework depending on their individual needs. An example of a modular program is the Discussing + Doing = Daring program (DDD, e.g., van Steensel et al., 2022). Originally, DDD was a face-to-face generic CBT program for childhood anxiety (Bögels, 2008), but was recently adapted to include separate modules (i.e., psychoeducation, task concentration, cognitive restructuring, relaxation and mindfulness, experiments, exposure, parental involvement, and relapse prevention). In the trial assessing this modular version (van Steensel et al., 2022), the modules psychoeducation and relapse prevention were mandatory in the first and last session, respectively. For all other sessions, therapists and clients collaboratively selected the modules. An advantage of working with modules is that the therapist can either skip or repeat certain sessions based on the individual needs of the child. There is some evidence suggesting that using a modular approach leads to better treatment outcomes for childhood anxiety disorders, although the evidence is still limited (e.g., van Steensel et al., 2022).

Empirical Evidence for the Importance of Homework

In the adult literature, several studies emphasize the importance of homework and find that homework compliance predicts treatment outcome (e.g., Schmidt & Woolway-Bickel, 2000; Westra et al., 2007). Three meta-analyses underscore the significant influence of homework compliance on treatment effectiveness across various symptoms, including anxiety (Kazantzis et al., 2010; Kazantzis et al., 2016; Mausbach et al., 2010; see also LeBeau et al., 2013). For example, in a meta-analysis of 23 studies conducted between 2000 and 2008, involving 2183 participants, a small-to-medium effect size for homework compliance was found on anxiety outcomes (Mausbach et al., 2010).

In the child literature, however, the empirical evidence for the importance of homework and the effect of homework compliance on treatment outcome on childhood anxiety is scarce, with only three empirical studies, and the evidence is far less conclusive (Arendt et al., 2016; Hughes & Kendall, 2007; Lee et al., 2019). Therefore, we also included studies here on other internalizing childhood disorders (depression: Clarke et al., 1992; Shrik et al., 2013; Simons et al., 2012; obsessive compulsive disorder [OCD)]: Park et al., 2014). One of the first studies reporting on the effect of homework compliance on treatment outcome in children was on depression (Clarke et al., 1992). Clarke and colleagues (1992) did not find any evidence for the effects of homework completion on treatment outcome. A later study by Shirk and colleagues (2013) on childhood depression confirmed these results. Hudson and Kendall (2002) were among the first to discuss the importance of homework specifically for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders; however, they did not empirically test whether homework compliance influenced treatment outcome. In 2007, Hughes and Kendall were the first to empirically test the effect of homework compliance in children with an anxiety disorder with their Coping Cat program. In this study, homework compliance did not predict treatment outcome. A later study using the Coping Cat program for children and adolescents confirmed these earlier findings (Lee et al., 2019). In line with these studies, Arendt and colleagues (2016) did not find an association between homework compliance and treatment outcome for Cool Kids, another generic CBT anxiety program.

One of the first studies to provide evidence that homework compliance-predicted treatment outcome was reported by Simons and colleagues (2012). They found that homework completion between treatment sessions predicted treatment outcome in adolescents with depression. Another study by Park and colleagues (2014) found evidence for the importance of homework compliance when studying the effects of d-cycloserine (DSC; DSC is used as an adjunctive medication and has been demonstrated to facilitate fear extinction) on homework compliance in a group of children with obsessive–compulsive disorder. They did not find that children who took DSC had a higher homework compliance than children who did not take DSC. However, they did find a significant main effect of homework compliance across conditions. Children with higher homework compliance showed more improvement in OCD symptom severity.

Reasons for these Mixed Findings

The previous section showed that, while the addition of homework practice in adults consistently adds to the effects of CBT, for children, studies are scarce, and the findings are mixed at best. Although these findings seem to downplay the importance of homework for CBT in childhood anxiety disorders, such a conclusion would be premature, as the evidence base is too small to draw strong conclusions. There are many important lessons that can be learned from the studies conducted so far and from the larger evidence base in adults. This section will critically review several methodological and theoretical factors addressing the mixed results on the effect of homework. In the following section, recommendations for homework programs are formulated based on these factors.

First, the mixed findings could be related to child, parent, and therapist factors. In general, individuals do not spend a lot of time on their homework assignments due to a variety of reasons, including lack of time, low motivation (Carroll et al., 2005; Detweiler & Whisman, 1999; Nock & Kazdin, 2005), lack of interest (Merry et al., 2012), not fully understanding the homework (Dozois, 2010), or (emotional) avoidance (Dobson et al., 2014; Hofmann, 2013). Additionally, especially in children, it is suggested that parents may also play a role in homework adherence (Arendt et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2019). Presumably, parents play an important role in facilitating homework exercises by providing support, resources, or simply enabling access to certain situations for exposure to occur (Clarke et al., 2015). A lack of support or resources may be one of the reasons why homework programs are not as effective as they could be (see also, Wilansky et al., 2016). Another reason that homework might not be as effective as it could be is due to therapist factors. For example, therapists might feel that they do not have sufficient time during the therapy session, perceive resistance of the child to do homework, or be concerned that the child is not able to handle the homework (Kelly & Deane, 2011). It seems important to take these child, parent, and therapist aspects into account when developing homework programs and evaluating the effects of homework in future studies.

Second, only a handful of studies investigated the effect of homework on treatment outcome in childhood internalizing problems, including anxiety, and the large majority of these studies mention methodological issues as one of the reasons for the mixed findings. One of the issues that was discussed includes the use of different dependent variables, such as the time spent on homework, proportion of task completion, and number of tasks completed. Additionally, there was large variability across studies in when the effect of homework was measured, for example, during treatment, post-treatment, or during follow-up. In addition, another study suggested that it might be more difficult to reliably measure the amount of time spent on homework in children, as children might find it challenging to keep track of their practice time (Arendt et al., 2016). These different outcomes, differences in time of measurement, and reliability of the measurements may have led to different and therefore inconsistent findings (see also, Kazantzis et al., 2016). Alternatively, focusing on qualitative ways of looking at homework might yield different insights into possible strategies and outcomes. For example, a child might not spend much time on homework, but the time spent might be very meaningful and high in quality (see also, Kazantzis et al., 2016). Indeed, a study on adults with a panic disorder (Schmidt & Woolway-Bickel, 2000) found that the quality of homework was a better predictor of treatment outcome than the quantity of the homework. This hypothesis, however, has not been examined in children.

Third, theoretical factors should be discussed as possible explanations. As discussed above, the content of CBT-based homework programs generally reflects the broad scope of elements that forms the generic CBT programs for childhood anxiety. This is based on the principle that session content should be practiced at home to ensure adequate mastery of skills and to stimulate generalization of skills to the home environment and beyond (Kazantzis & L’Abate, 2005). However, due to a general lack of mechanistic research focusing on working mechanisms of CBT for child anxiety, it is unclear to what extent all these individual elements add to the efficacy of CBT for anxiety (Kazdin, 2018). It could theoretically be expected that certain homework assignments may tap more into core working mechanisms of CBT, whereas other homework assignments may not.

Leading theories of both the maintenance of anxiety disorders and the working mechanisms of CBT find common ground: a focus on correcting dysfunctional cognitions and anxious expectations using corrective techniques is key for treatment success (e.g., Beck, 1976; Craske et al., 2022; Spence & Rapee, 2016). In this regard, exposure is considered the most effective working element of CBT for childhood anxiety and involves the repeated confrontation with feared stimuli or situations in the absence of the feared outcome to correct these dysfunctional, anxious expectations, and beliefs (Craske et al., 2022; Crawley et al., 2013). This conclusion has found support in several studies in adult anxiety disorders (e.g., Craske et al., 2022; Pittig et al., 2023) and a handful of studies in the childhood anxiety disorders field (Kendall & Treadwell, 2007; Mobach et al., 2021; Whiteside et al., 2019). Practicing with feared stimuli or situations allows for generalization and successful experiences in developing non-catastrophic associations that may maximize treatment outcomes (Bandarian-Balooch et al., 2015; Cammin-Nowak et al., 2013; Kendall et al., 2005; Tiwari et al., 2013).

There is no theoretical reason to assume that homework assignments have a fundamentally different working mechanisms than CBT programs themselves. Therefore, if some aspects of a homework program are more important than others (e.g., exposure), the large variability (reflecting the full range of CBT elements) in homework programs included in the studies reviewed above may dilute the effects of certain homework assignments that reflect these supposed working elements of CBT. Indeed, some studies suggested this hypothesis as a possible explanation for their insignificant findings (Arendt et al., 2016; Hughes & Kendall, 2007; Parker et al., 2023). This reasoning was partly confirmed in one of the few studies that did find an effect of homework on treatment outcome (Park et al., 2014). In this study, the tested homework program almost exclusively consisted of exposure-related exercises and relapse prevention. Also, other studies in adults found evidence for the fact that homework adherence was found to be more important at certain times during treatment, such as at the start of treatment (Westra et al., 2007), which might indicate that some aspects or timing of homework might be important (Simpson et al., 2011; Westra et al., 2007).

Keeping in mind that (1) from a theoretical perspective, adherence to homework exercises during and after treatment are crucial and (2) the difficulties observed in clinical practice in obtaining sufficient homework compliance (see e.g., Hudson & Kendall, 2002; Lundkvist-Houndoumadi et al., 2016), a logical conclusion and recommendation would hence be to focus homework exercises on the theoretically important and empirically supported working elements. That is, exposure to break the avoidance cycle and correct dysfunctional cognitions and anxious expectations.

Key Elements of Homework for Childhood Anxiety Disorders

In the previous section, three overarching themes were discussed in relation to a general lack of homework effects for childhood anxiety in the studies conducted so far: child, parent, and therapist factors; methodological factors (e.g., quality and quantity of homework); and theoretical (homework content) factors. In this section, we have translated the shortcomings addressed above into structural, key elements that should be addressed to improve CBT-based homework programs for child anxiety. To this end, we have compiled a list of 11 key elements and conditions that evidence-based homework programs should consider and/or incorporate based on the literature. We have grouped these elements according to the three overarching themes discussed above, starting with the theoretical factors and working toward more specific child, parent, and therapist factors. See Table 1 for a concise overview of the key elements described below.

Theoretical factors:

-

1.

Setting the stage for expectancy violation. In formulating the homework exercises, a focus on expectancy violation and corrective learning instead of on fear reduction is key. Craske and colleagues (2022) recently formulated a theoretically and empirically supported exposure plan with key points that should be addressed when planning both guided and unguided exposure. The following principles should be adhered to maximize prediction error, remove distraction(s), remove safety behaviors and signals, and include mental rehearsal after the homework exposure exercises (see key element 9). A well-designed exposure exercise should include a focus on testing a specific anxious expectation about a feared stimulus or situation that the child rates as very believable (i.e., has a high threat expectancy rating). The exposure exercise should be set up in such a way that it includes a high chance of experiencing a disconfirmation of the anxious expectation. Maximizing the prediction error between what the child expects will happen (e.g., ‘The dog will bite me’) and what happens in reality (e.g., the dog licks the child’s hand and does not bite) is very important in increasing these chances. To reach this goal, it is paramount that safety signals and safety behaviors are removed (as much as possible) and no cognitive interventions aimed at reducing the believability of the threat expectancy (e.g., ‘how many children get bitten by a dog every year?’) precede the exposure exercise. It is beyond the scope of this article to review all principles in detail; please see Craske and colleagues (2022) for an in-depth discussion. Adequate therapist guidance and therapist modeling during guided exposure exercises within sessions can help with adhering to these rules (see key element #4). In addition, training the parents to guide the child with the more difficult homework exercises or ensuring that the necessary materials or situations are facilitated is necessary for a successful exposure exercise (see key element #11).

-

2.

Multiple contexts. In close connection to key element #1, it is important that exposure exercises are conducted in a variety of internal and external contexts (e.g., at home, different varieties of the same stimulus (e.g., different types of dogs/spiders) outside, different public places, different emotional states), and in a variety of circumstances (e.g., with/without parents, siblings present) to generalize and consolidate the learning coming out of the expectancy violation: what the child expects will happen does not take place in many different contexts and circumstances. Studies have shown that varied practice decreases the chance of fear/context renewal and, in the end, relapse (e.g., de Jong et al., 2019; Jacoby & Abramowitz, 2016; Maren et al., 2013). Homework exercises play an important role in achieving this goal, as the therapeutic context is often limited to practicing only a couple of these contexts and circumstances.

-

3.

Flooding versus gradual exposure. While guidelines for adult exposure exercises have incorporated ‘flooding’ instead of gradual exposure for a longer time, child CBT programs still mostly include gradual exposure using a hierarchy of exposure exercises, starting with the easiest and least anxiety-provoking exercise and ending with the most difficult and fear-inducing exercise (Davis et al., 2019; Mobach et al., 2020). For spider phobia, an example of gradual exposure is starting with looking at pictures of spiders before progressing to more fear-provoking exercises, such as looking at live spiders or handling them. Flooding, in contrast, does not follow a fear hierarchy. Instead, it may incorporate starting with exercises that provoke more fear, potentially including the intended end goal of therapy, such as handling live spiders. Flooding has been associated with larger reductions in dysfunctional anxious expectations during exposure exercises in adults with anxiety disorders (Craske et al., 2022). However, in child anxiety, to the best of our knowledge, there have not been any studies specifically testing flooding versus gradual exposure in relation to treatment outcome or reduction in critical maintenance mechanisms of anxiety disorders. This being said, a study by de Jong and colleagues (2023) has compared gradual exposure in small steps versus exposure in larger steps. The results indicated that large steps were not more effective than taking small steps in reaching the child’s goals and in anxiety severity at post-treatment. The authors discuss the likely explanation that taking smaller steps resulted in children being exposed to a larger variety of fearful stimuli/situations, which (in relation to key element #1 and #2) likely led to more generalization of the learned outcomes. In conclusion, these findings lead to repetition of the message above that abiding by the expectancy violation set-up in combination with exposure in multiple contexts is important. Nonetheless, more research on the possible differences in efficacy between flooding and gradual exposure in childhood anxiety should be included on the agenda for future research.

-

4.

Mental rehearsal. Including mental rehearsal in-between sessions and before and after homework exercises can act as an augmentation strategy to exposure-based exercises. Mental rehearsal has two important advantages: it stimulates and strengthens retrievability of the learning experience (compared to the original fear association) from memory and enhances motivation for future exposure exercises (McGlade & Craske, 2021). Homework programs can incorporate various forms of mental rehearsal and memory consolidation, including taking pictures/videos of successful exposure experiences and including the initial anxious expectation and the newly formulated realistic expectation. These tools can stimulate the child to reflect on these experiences and enhance consolidation into memory, which may increase feelings of self-efficacy and can aid in restructuring dysfunctional cognitions (Beidas et al., 2010). For possibilities in including mental rehearsal in exposure practice and a discussion on the potential working mechanisms of mental rehearsal (e.g., prolonged [imaginal] exposure), see also McGlade and Craske (2021).

Methodological factors

-

5.

Personalized exposure exercises. Guidelines for formulating homework exercises explicitly include personalizing the exposure exercises to ensure that the exercises match the skill-level and personal characteristics of the child (see Tompkins, 2002, for guidelines). Personalizing exposure exercises acknowledges the heterogeneity of each anxiety disorder and each child (Peterman et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017) and the large variety of anxious expectations children with anxiety disorders present with during treatment. For example, not all children with a social anxiety disorder fear negative evaluation by adults (APA, 2013). Giving all children with a social anxiety disorder an exercise focused on exposure to possible scrutiny by an adult would fail to meet the needs of the child that does not feel fearful for this exposure assignment, possibly resulting in a lack of commitment to the homework exercise. Integration of an adequate case conceptualization is therefore paramount.

-

6.

Psychoeducation. Psychoeducation plays a large role in the beginning of exposure-based CBT and is hence included in all CBT protocols. Psychoeducation is crucial to increase understanding of how anxiety complaints are maintained and how exercises can help the child to reduce their anxiety complaints. It is a way of preparing the client for therapy by providing information on the complaints and treatment rationale. Additionally, it can help with normalization, establishing a good working relationship between therapist and client and increasing engagement with therapy (see Grills et al., 2023 for an extensive review on the role of psychoeducation in childhood CBT). Starting treatment with psychoeducation can thus increase motivation in both children and parents and ensure client and therapist are in agreement on the treatment goals and approach. However, the importance of continuous psychoeducation on the how and why of exposure exercises to ensure adequate practice at home is often underestimated. For example, repeating the message that safety behaviors play an important role in maintaining anxiety just before an exposure exercise could motivate the child to leave their safety behavior behind when doing the exposure exercise. Additionally, providing easy access to psychoeducation about homework- and CBT-related topics in a homework program offers low-level support to parents and their child whenever they need to have access to information when outside of the therapeutic context. It is important to mention that there is evidence for the effectiveness of psychoeducation as an intervention by itself (e.g., Baourda et al., 2022), but the added value of psychoeducation in relation to homework has not yet been tested.

-

7.

Contingency management. Contingency management is a standard component in treatment for childhood anxiety (e.g., Kendall, 1990; Podell et al., 2010; Rapee et al., 2009) and should be considered an important component of homework programs as well. Stimulating a child’s engagement in homework exercises, however, should be based on theory (Kazantzis & Miller, 2022). Operant conditioning principles have guided engagement principles in therapy for the last several decades (e.g., Becker et al., 2012; Skinner, 1968), stating that behavior that is reinforced is more likely to be repeated in future. Incorporating rewards and reinforcements can be done in various ways, including positive feedback after completed exercises and allowing the child to choose rewards (e.g., selecting what to eat for dinner or engaging in family activities). Contingency management is also often easily implemented in mHealth programs, where gamification is gaining momentum (e.g., Dennis & O’Toole, 2014). Gamification of mHealth for homework programs has the potential to include gaming elements (e.g., unlocking fun games after successful completion of homework exercises or collecting points) that have been associated, among other things, with improved adherence to health interventions and enhanced intrinsic and extrinsic user motivation (Dennis & O’Toole, 2014; Ferreira et al., 2014). Directly connecting a child’s goals to a certain, self-chosen reward can, therefore, stimulate the child to reach their goals.

Child, parent, and therapist factors

-

8.

Therapist guidance and clear instructions. Homework programs can be self-guided or therapist guided, which may also vary depending on the phase of the therapy that the homework program is used in (during treatment versus after treatment). Therapist-guided homework programs can include all sorts of different forms of support, ranging from automated reminders of the completed homework exercises to regularly scheduled telephone contact with the therapist. To the best of our knowledge, no research has been done specifically on the role of therapist support in CBT homework programs. In general, studies have shown that regular contact with a therapist during online or bibliotherapy CBT formats substantially increases usage of the program, improves treatment outcomes, and is related to lower dropout rates (see for a review, Baumeister et al., 2014; Marks & Cavanagh, 2009; Stasiak et al., 2016). Specifically, for mHealth-supported treatment, inclusion of therapist support tends to be more effective as it increases accountability and motivation (Wright et al., 2019).

-

9.

Self-monitoring. Self-monitoring can take on many forms, including asking the child for specifics on the exercise (e.g., ‘what did you do during the exercise?’) and how the child feels (e.g., ‘how anxious are you now?’). Although many of these questions are helpful, key questions that should be asked focus on what the child has learned with regards to their anxious expectation to enhance expectancy violation (Craske et al., 2022, see also key element #1) and memory consolidation (Beidas et al., 2010, see also key element #4). Including some form of self-monitoring in a homework program guides the child toward what needs to be consolidated in learning before and after the exercise, can greatly enhance reflection on what is learned (i.e., ‘did your anxious expectation come true’), and holds an important place in a self-guided exposure exercise. In this way, self-monitoring is a means to an end, namely enhancing expectancy violation and memory consolidation.

-

10.

Involvement of parents. Although the inclusion of parental involvement has not led to better treatment outcomes on the treatment level (see for a systematic review, Byrne et al., 2023) for childhood anxiety, involving parents could enhance the likelihood of completing homework exercises. Parents play an important role in facilitating the child with the right materials and situations (e.g., arranging a car ride to a certain setting or ensuring that siblings are out of the house to decrease distractions) outside of the treatment context. Involving parents early in the treatment process as ‘facilitators’ to ‘transfer control’ (Ginsburg et al., 1995; Wei & Kendall, 2014), giving parents instructions on what to look out for during the exposure exercises (e.g., safety behaviors), and directing them to the homework forms to be completed before and after the exercise can be effective (Manassis et al., 2014) and facilitate (qualitatively good) homework completion. It is crucial, however, to remind parents of the importance of their role in the exposure exercises, provide psychoeducation on family accommodation, and highlight the possibility of acting as a safety person to ensure setting the stage for adequate expectancy violation (Byrne et al., 2023; Craske et al., 2022; Lebowitz et al., 2016).

-

11.

Co-creation and user-friendliness. Regardless of the format of the homework program (e.g., paper based, online, or smartphone application based), the homework program should be user-friendly and based on generic guidelines for improving homework outcomes (Dozois, 2010; Wilansky et al., 2016). These guidelines include, among others, the importance of shared decision-making, formulation of clear and specific exercises, and the discussion of dysfunctional attitudes related to non-compliance (e.g., ‘I can’t do homework, because….’). Many of these guidelines follow the general process of co-creation. Co-creation plays an important role in the formulation of homework assignments, as well as in formulating the homework program itself. Treatment-seeking children and their families represent a wide range of different backgrounds, developmental stages, and wishes. Co-creating homework programs with these end-users (i.e., the child and their parents, therapists) can increase the chance that the homework program format has an easy interactive format and can be easily incorporated into a child’s life and treatment program. A user-centered iterative development process that involves all end-users, including children, families, researchers, and therapists (and IT specialists in the case of mHealth), is therefore important and increases the chance that children and their families adequately benefit from their exposure exercises (McCurdie et al., 2012).

Toward a New Way of Incorporating and Delivering Homework in Current CBT Programs

When developing and evaluating new ways to incorporate homework in current CBT programs for childhood anxiety disorders, it is important to consider the different aspects described in the previous sections. The key question is how to optimally integrate these 11 elements into existing CBT programs and how to best deliver homework. Historically, homework programs have been delivered through paper-and-pencil methods, often in the form of booklets or loose forms provided to a child after a session. One option is to directly adapt these paper-and-pencil booklets. An advantage of adapting the booklets is that it might be less work, the child can easily go back in the booklet or look at it after treatment, and the child can easily show the booklet to others. Disadvantages of these programs, however, are that the therapist have limited insight into the child’s activities at home and cannot easily help the children at home when the child is facing problems. Additionally, the child needs to remember to bring the paper-and-pencil booklets, and the booklets are usually printed and follow a standard order, which might not suit every child.

Another option is to leverage technological solutions for the delivery and adaptation of existing homework programs. While online CBT programs already incorporate technology and can utilize the aforementioned 11 points to further enhance their programs, face-to-face programs could also benefit from incorporating technological solutions as an add-on to their existing programs, facilitating home practice. Blended care, such as mHealth apps, holds the potential to overcome some of the challenges outlined in the previous section (Tang & Kreindler, 2017). For instance, an app could provide guidance on exercises and necessary preparations, better individualize the program by selecting or creating exercises tailored to the specific child, provide information about home practice, send reminders, incorporate motivational game elements, and track progress to provide therapists with insight into the homework process (Berry & Lai, 2014; Muroff & Robinson, 2022). Additionally, apps have certain advantages over online environments; they are generally more user-friendly, can be used offline (unlike online environments that always require an internet connection), and can store photos and videos only on the child’s private device, avoiding the need for uploads to an online environment, which is a large advantage with regard to privacy.

The use of mHealth apps is indeed on the rise, reflecting the growing interest in leveraging technology to enhance mental health care (Hollis et al., 2017). Currently, a multitude of Mhealth apps are available, offering exercises to address anxiety complaints. However, these apps are seldomly tested for effectiveness. Despite the consensus about the need for an evidence-based approach to childhood anxiety (Higa-McMillan et al., 2016), a review about childhood anxiety apps by Bry and colleagues (2018) concluded that approximately half of the publicly available apps featured only one of the evidence-based features listed above and merely about one-fourth included two or more evidence-based features. Unfortunately, none of these apps cover the complete range of evidence-based features. Since the publication of Bry’s et al.’s review in 2018, there have been no notable improvements in this area.

Currently, several mHealth apps are available for childhood anxiety that were developed within the academic setting, including MindClimb (Newton et al., 2020), REACH (Stoll et al., 2017), SmartCAT 2.0 (Silk et al., 2020), and Anxiety Coach (Carper, 2017; Whiteside, 2016; Whiteside et al., 2019). These apps were designed as add-ons to individual or group-based CBT, primarily aiming to assist youth in completing homework assignments between therapy sessions. Each of these apps incorporates some of the eleven mentioned aspects discussed earlier. For instance, all three apps feature a form of self-monitoring; MindClimb uses questions before and after each exercise and provides an overview of schedules events (Newton et al., 2020), REACH uses daily diary reporting (Patwardhan et al., 2015; Stoll et al., 2017), and Anxiety Coach tracks anxiety levels (Carper, 2017; Whiteside, 2016; Whiteside et al., 2019). They also include contingency management, such as positive messages and points are awarded for an event ladder completion in MindClimb (Newton et al., 2020), and digital points in SmartCAT 2.0 (Pramana et al., 2018; Silk et al., 2020). However, there are still important evidence-based elements that are either missing or under development. Only Anxiety Coach has consistently prioritized exposure as its main focus, utilizing a database of non-individualized exercises. The app does not allow for fully tailored fear hierarchies, but it does enable therapists to include individualized exercises (Carper, 2017; Whiteside, 2016; Whiteside et al., 2019). It should be noted, however, that SmartCAT 2.0 has made significant advancements in this regard. In contrast to the initial version, it now includes individualized exercises suggested by the therapist (Pramana et al., 2018; Silk et al., 2020). Since these apps are typically used as an add-on to therapy with a professional, it is crucial to comprehensively evaluate the full programs. This is particularly important as the quality of elements, such as exposure exercises, can vary significantly, and the mere inclusion of exposure exercises does not guarantee alignment with the key elements described earlier.

Thus, while current traditional CBT programs address some important aspects of homework and recently developed apps incorporate certain features, it is noteworthy that no single program currently integrates all essential elements while emphasizing the key working elements of CBT. Moreover, it is important to acknowledge that the effectiveness of these programs depends on how well therapists are trained in their ability to connect the face-to-face sessions to the homework program. What is needed is a comprehensive treatment package that integrates face-to-face or online treatment with an evidence-based homework program, possibly delivered through an app. This approach would ensure that all therapists undergo thorough training to maximize its effectiveness. The next section aims to bridge this gap by presenting a cohesive and well-integrated program, covering the in-session program, homework program, and how therapists are trained to seamlessly integrate these components into one comprehensive package.

Development of a New Way to Enhance Homework in CBT for Childhood Anxiety Disorders

In order to address the 11 key features described before, a new homework program, The Kids Beat Anxiety (KibA) homework program (Klein et al., 2023), was recently developed as an add-on to an existing childhood CBT program. Specifically designed to enhance the One-Session Treatment (OST) protocol for childhood-specific phobias (Ollendick et al., 2015; Öst & Ollendick, 2001), this comprehensive OST program starts with an extensive intake to assess the specific phobia and identify any additional concerns. Next, a cognitive behavioral analysis is conducted to fully understand the child's dysfunctional beliefs and factors influencing their fear, such as context, companions, or the size of the feared object. The cognitive analysis is followed by a three-hour massed exposure session, a key part of OST. During this session, children engage in practice with various stimuli (e.g., three different dogs of different sizes and activity levels) under the therapist’s guidance, with the aim of achieving significant progress (for more details, see Öst & Ollendick, 2001; Ollendick et al., 2015). To sustain and extend these improvements, continued practice outside of therapy is vital, and this is where the KibA homework program comes into play.

One week following the massed exposure session, the therapist and the family reflect together on the progress made in the session and the therapist emphasizes the importance of continuing practice at home for at least four weeks. During this session, the therapist explains the homework procedure and provides guidance on what to do in case of a setback. The KibA app, primarily focusing on exposure, becomes an essential tool during this period.

During the session, the therapist and the child (along with parents) collaboratively create 10 individualized exposure exercises that focus on expectancy violation and corrective learning (key elements 1, 5, 10). Each exercise includes three difficulty levels to create multiple contexts (key element 2). For example, an exercise might involve “walking to the playground next to the dog park,” with levels ranging from walking with a parent during peak dog-walking times (bronze) to going alone during a quiet period (silver) or during busy dog-walking hours (gold). The child is allowed to freely choose from the first three exercises and whether they want to do the easier or more difficult version of an exercise. After completing 5 out of 9 levels of the first three exercises, the next three exercises are unlocked. In this way, gradual exposure is combined with flooding (key element 3). Prior to and following each exercise, children answer different questions to self-monitor their result (key element 9) and to be able to challenge their expectancies (key element 1). Besides discussing the individualized exposure exercises, the therapists and the family also discuss individualized rewards that can be earned by completing the exposure exercises and its associated goals. An example of a goal is to take photos and videos during an exposure exercise and to later re-watch these photos and videos which help with mental rehearsal (key element 4). The child earns coins by completing exposure exercises and achieving goals, which they can exchange in the store for a reward. Parents are asked to provide a surprise reward, which the child can earn by completing the program (key element 7). In addition, the app includes instructions and psychoeducation in case the child forgets anything about the instruction or has a setback (key element 6).

Children use the app for four weeks at home with the goal of practicing on a daily basis, and the therapist provides weekly contact to discuss progress and to address potential challenges (key element 8). Importantly, all therapists receive training in the OST procedure and app usage, including guidance for massed exposure sessions and examples of suitable exercises and rewards. Initial case supervision and ongoing sessions are offered to ensure effective implementation. The app was built in co-creation and is currently tested on effectiveness in a randomized controlled trial (key element 11).

Please find a further elaboration of all features of the KibA homework program based on the 11 recommendations and its development process in appendices A and B. Appendix A provides a comprehensive understanding of how this homework program is designed, and appendix B provides an overview of the development and implementation. A summary of the key elements is also provided in Tables 2 and 3, and Fig. 3 provides screenshots of the app, highlighting its main features.

Discussion

The purpose of the current review was to give an overview of the existing literature on CBT-based homework programs for childhood anxiety in order to provide new directions for enhancing treatment outcomes utilizing homework programs. More specifically, we focused on three aspects in our review. First, we provided a brief overview and examples of how treatment programs for childhood anxiety incorporate homework. Following this, we presented an overview of the empirical literature available on the effect of homework on treatment outcomes in childhood CBT programs. Second, we described the key elements that are important to be included in homework based on the available evidence. Third, we explored how digital health innovations, such as an app, could facilitate the homework process, including an example of the development of such an app.

The literature review indicates that CBT programs, including programs for childhood anxiety disorders (e.g., Bögels, 2008; Kendal & Hedtke, 2006a, 2006b; Ollendick et al., 2015; Rapee et al., 2006; Spence et al., 2006), have generally emphasized between-session and post-treatment homework practice. However, most programs for childhood anxiety disorders are generic in nature, and homework often directly mirrors the broad range of topics that are addressed during the sessions. While there are enough reasons to incorporate homework in childhood CBT programs and adult studies found small-to-medium effect sizes for homework compliance on anxiety outcomes, empirical research in childhood anxiety disorders is scarce (we only found three studies that specifically focused on childhood anxiety; Arendt et al., 2016; Hughes & Kendall, 2007; Lee et al., 2019). We therefore focused on empirical research in childhood internalizing disorders in our review, revealing mixed results. Several reasons were mentioned that could explain these mixed results including the (1) (theoretical) content that is addressed during the homework, (2) methodological issues, and (3) child, parent, and therapist factors. Clearly, more research is needed to investigate the effects of homework on treatment outcomes in childhood anxiety disorders. These considerations can guide the optimization of homework program content and inform future studies aimed at building an evidence base for CBT-based homework programs for childhood anxiety.

A first step in optimizing homework programs is to critically evaluate their content, considering both theoretical foundations and empirical evidence regarding potential active components of homework. Empirical studies suggest that certain aspects of homework may be more effective than others (Park et al., 2014; Simpson et al., 2011; Westra & Dozois, 2007). For instance, homework activities like reading through psychoeducation material or completing cognitive restructuring exercises may be less effective than engaging in actual exposure exercises, which could more optimally make use of the efforts invested by children and their families in completing homework exercises. This aligns with recent developments in both adult and childhood CBT, emphasizing a growing focus on the active elements of CBT. The consensus in adult CBT studies for anxiety is that cognitive restructuring and exposure are primary, active elements driving CBT, as demonstrated in various studies (e.g., Beck, 1976; Craske et al., 2022). Unfortunately, there is currently a lack of studies in children investigating the working mechanisms or crucial elements of CBT for childhood anxiety (e.g., Kendall & Treadwell, 2007; Mobach et al., 2021; Radtke et al., 2021; van Steensel et al., 2022). Clearly, more research is needed to better understand the factors influencing treatment outcomes, especially as most homework follows the in-session content. Particularly considering that (1) from a theoretical perspective, adherence to homework exercises during and after treatment are crucial and (2) the difficulties observed in clinical practice in obtaining sufficient homework compliance (see, Hudson & Kendall, 2002; Lundkvist-Houndoumadi et al., 2016). A logical conclusion and recommendation would be to design homework exercises based on the theoretically important and empirically supported working elements. That is, exposure to correct dysfunctional cognitions and anxious expectations.

Secondly, in addition to critically assessing the content of current CBT programs and associated homework, we must consider child, parent, and therapist factors. In general, practicing at home can be challenging due to factors, such as low motivation, lack of time, insufficient self-guidance, emotional avoidance, and difficulty understanding the assignments, as often noted in the literature as reasons for low adherence (Tang & Kreindler, 2017). Furthermore, a lack of parental support or concerns from therapists about the child’s ability to handle the homework, along with time constraints during the therapy session to discuss the homework (Kelly & Deane, 2011), may negatively affect homework practice in children. Therefore, it is important to consider these different factors when designing, delivering, and evaluating homework programs. Collaboration with children, parents, and therapists in the design of homework programs is essential. Additionally, providing therapists with effective training on delivering optimal treatment is important for the successful implementation of homework.

Finally, several methodological issues were mentioned that are informative to take into account when evaluating homework programs in future studies. There is, for example, some indication that homework in a specific stage of the treatment is more important than in other stages (Simpson et al., 2011; Westra & Dozois, 2007). Also, some studies found that focusing on qualitative aspects (such as quality of the homework) rather than on quantitative aspects (such as number of minutes spent on the homework) better predicted treatment outcome. Moreover, how homework adherence is measured (e.g., during treatment vs following treatment) may give different effects, and it seems a challenge to reliably measure homework adherence, especially in children. In this respect using an Mhealth technology, such as an app, could solve part of the problems as it automatically tracks the number of completed exercises, when the child spends time on homework and total time spent per activity.

To further facilitate the re-evaluation of current homework programs, eleven key elements, based on the most recent theoretical and empirical insights and research, were provided that are important to take into account when redesigning and evaluating homework for CBT programs for childhood anxiety disorders. As a first attempt to develop a homework program that includes all mentioned important elements, we developed the KibA homework program including an app for children with a specific phobia that could serve as an example of how homework could be improved. While developing this program, we learned three lessons that are important to take into account when developing a new homework program. First, the feedback from the child panel and therapist panel led to several major improvements in the program. As a result, we added more game elements, changed the layout to include more attractive colors, included more child-friendly instructions, and made the app more standalone with a monitoring role for therapists. Second, providing mock-up versions of the program in an early stage and the beta-versions quite early in the process helped the panels to visualize what the program could look like. This helped the panels to provide detailed feedback and recommendations for newer versions which was very helpful for the IT team that did not have any experience in making software especially for children with an anxiety disorder. Third, the close collaboration between researchers, IT specialists, and the end-users was instrumental in our end product. Researchers were crucial in order to provide theory-based features. IT specialists made sure the app was well designed and programmed and followed all privacy and data management requirements. The end-user feedback was crucial for user-friendliness. This qualitative feedback from all parties enhanced our understanding of the importance of co-developing a mHealth with end-users, and our understanding of the importance of multiple testing rounds to develop user-friendly mHealth apps (Barnum, 2020).

Conclusion

The current review contributes to a growing body of support, suggesting the need for a critical re-evaluation of CBT programs for childhood anxiety disorders to enhance treatment outcomes (e.g., Craske et al., 2022; James et al., 2013; Levy et al., 2022). This review especially focused on the influence of homework on treatment outcome, recognizing that improving the quality of homework might have the potential to help children overcome their fears, reduce anxieties, and minimize relapse following treatment (Kazantzis et al., 2016). The lack of impact observed in current homework programs on treatment outcomes was explored, along with recommendations for future studies. To further guide the re-evaluation of current homework programs several recommendations for future studies were provided, along with a list of eleven key elements. These key elements, grounded in the most recent theoretical and empirical literature, are important considerations when (re-)designing and evaluating homework for CBT programs for childhood anxiety disorders.

As an example how to enhance the effectiveness of homework programs, we developed the KibA homework program, including an app, as part of the One-Session Treatment program commonly used to treat childhood-specific phobias. While we designed the app for children with a specific phobia, our app could easily be modified to incorporate homework for other anxiety disorders or other mental health disorders if found effective in our randomized clinical trial (Klein et al., 2023). Given that exposure is used as a treatment for various disorders, such as obsessive–compulsive disorder, panic disorder, separation anxiety, social anxiety, and more, the app might also facilitate home practice in these mental health disorders. Furthermore, with adjustments in program layout and instructions, the app might extend its utility to other age groups. The KibA homework program, including the app, is relatively standalone, with therapists adding individualized exercises and rewards via the online dashboard. This balance between autonomy and therapist involvement aims to support and motivate children while holding them accountable. In terms of future research, we hope that this review sets the stage and stimulates further investigation into redesigning and evaluating the effect of homework programs, including mHealth apps, in the treatment of various clinical child disorders.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

Arendt, K., Thastum, M., & Hougaard, E. (2016). Homework adherence and cognitive behaviour treatment outcome for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 44(2), 225–235.

Bandarian-Balooch, S., Neumann, D. L., & Boschen, M. J. (2015). Exposure treatment in multiple contexts attenuates return of fear via renewal in high spider fearful individuals. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 47, 138–144.

Baourda, V. C., Brouzos, A., Mavridis, D., Vassilopoulos, S. P., Vatkali, E., & Boumpouli, C. (2022). Group psychoeducation for anxiety symptoms in youth: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 47(1), 22–42.

Barnum, C. M. (2020). Usability testing essentials: Ready, set... test!. Morgan Kaufmann.

Barrett, P. M., Lowry-Webster, H., & Turner, C. (2000a). FRIENDS program for children: Parents’ supplement. Australian Academic Press.

Barrett, P. M., Lowry-Webster, H., & Turner, C. (2000b). FRIENDS program for children: Group leaders manual. Australian Academic Press.

Barrett, P. M., Lowry-Webster, H., & Turner, C. (2000c). FRIENDS program for children: Participants workbook. Australian Academic Press.

Baumeister, H., Reichler, L., Munzinger, M., & Lin, J. (2014). The impact of guidance on Internet-based mental health interventions—A systematic review. Internet Interventions, 1(4), 205–215.

Becker, E. M., Becker, K. D., & Ginsburg, G. S. (2012). Modular cognitive behavioral therapy for youth with anxiety disorders: A closer look at the use of specific modules and their relation to treatment process and response. School Mental Health, 4, 243–253.

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. International University Press.

Beck, A. T., & Dozois, D. J. (2011). Cognitive therapy: Current status and future directions. Annual Review of Medicine, 62, 397–409.

Beesdo, K., Knappe, S., & Pine, D. S. (2009). Anxiety and Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents: Developmental Issues and Implications for DSM-V. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 32(3), 483–524.

Beidas, R. S., Benjamin, C. L., Puleo, C. M., Edmunds, J. M., & Kendall, P. C. (2010). Flexible applications of the Coping Cat Program for anxious youth. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 17(2), 142–153.

Berry, R. R., & Lai, B. (2014). The emerging role of technology in cognitive–behavioral therapy for anxious youth: A review. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 32, 57–66.

Bögels, S. M., & Appelboom, C. (2008). Behandeling van angststoornissen bij kinderen en adolescenten: Met het cognitief-gedragstherapeutisch protocol Denken+ Doen. Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Bry, L. J., Chou, T., Miguel, E., & Comer, J. S. (2018). Consumer smartphone apps marketed for child and adolescent anxiety: A systematic review and content analysis. Behavior Therapy, 49(2), 249–261.

Byrne, S., Cobham, V., Richardson, M., & Imuta, K. (2023). Do Parents enhance cognitive behavior therapy for youth anxiety? An overview of systematic reviews over time. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 1–16.

Cammin-Nowak, S., Helbig-Lang, S., Lang, T., Gloster, A. T., Fehm, L., Gerlach, A. L., Ströhle, A., Deckert, J., Kircher, T., Hamm, A. O., Alpers, G. W., Arolt, V., & Wittchen, H. U. (2013). Specificity of homework compliance effects on treatment outcome in CBT: Evidence from a controlled trial on panic disorder and agoraphobia. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(6), 616–629.

Carper, M. M. (2017). Multimedia field test thinking about exposures? There’s an app for that! Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 24(1), 121–127.

Carroll, K. M., Nich, C., & Ball, S. A. (2005). Practice makes progress? Homework assignments and outcome in treatment of cocaine dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(4), 749.

Cartwright-Hatton, S., Roberts, C., Chitsabesan, P., Fothergill, C., & Harrington, R. (2004). Systematic review of the efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapies for childhood and adolescent anxiety disorders. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(4), 421–436.

Chatterton, M. L., Rapee, R. M., Catchpool, M., Lyneham, H. J., Wuthrich, V., Hudson, J. L., Kangas, M., & Mihalopoulos, C. (2019). Economic evaluation of stepped care for the management of childhood anxiety disorders: Results from a andomized trial. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 53(7), 673–682.

Clarke, G., Hops, H., Lewinsohn, P. M., Andrews, J., Seeley, J. R., & Williams, J. (1992). Cognitive-behavioral group treatment of adolescent depression: Prediction of outcome. Behavior Therapy, 23(3), 341–354.

Clarke, A. T., Marshall, S. A., Mautone, J. A., Soffer, S. L., Jones, H. A., Costigan, T. E., Patterson, A., Jawad, A. F., & Power, T. J. (2015). Parent attendance and homework adherence predict response to a family–school intervention for children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(1), 58–67.

Craske, M. G., Treanor, M., Conway, C. C., Zbozinek, T., & Vervliet, B. (2014). Maximizing exposure therapy: An inhibitory learning approach. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 58, 10–23.

Craske, M. G., Treanor, M., Zbozinek, T. D., & Vervliet, B. (2022). Optimizing exposure therapy with an inhibitory retrieval approach and the OptEx Nexus. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 152, 104069.

Crawley, S. A., Kendall, P. C., Benjamin, C. L., Brodman, D. M., Wei, C., Beidas, R. S., Podell, J. L., & Mauro, C. (2013). Brief cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious youth: Feasibility and initial outcomes. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20(2), 123–133.

Davis, T. E., III., Ollendick, T. H., & Öst, L. G. (2019). One-session treatment of specific phobias in children: Recent developments and a systematic review. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 15, 233–256.

De Jong, R., Lommen, M. J., de Jong, P. J., & Nauta, M. H. (2019). Using multiple contexts and retrieval cues in exposure-based therapy to prevent relapse in anxiety disorders. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 26(1), 154–165.

De Jong, R., Lommen, M. J., van Hout, W. J., Kuijpers, R. C., Stone, L., de Jong, P., & Nauta, M. H. (2023). Better together? A randomized controlled microtrial comparing different levels of therapist and parental involvement in exposure-based treatment of childhood specific phobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 100, 102785.

Dennis, T. A., & O’Toole, L. J. (2014). Mental health on the go: Effects of a gamified attention-bias modification mobile application in trait-anxious adults. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(5), 576–590.

Detweiler, J. B., & Whisman, M. A. (1999). The role of homework assignments in cognitive therapy for depression: Potential methods for enhancing adherence. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6(3), 267.

De Vries, Y. A., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Borges, G., Bruffaerts, R., Bunting, B., Caldas-de-Almeida, J. M., Cia, A. H., de Girolamo, G., Dinolova, R. V., Esan, O., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Hu, C., Karam, E. G., Karam, A., Kawakami, N., Kiejna, A., et al. (2019). Childhood generalized specific phobia as an early marker of internalizing psychopathology across the lifespan: Results from the World Mental Health Surveys. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 1–11.

Dobson, K. S., Quigley, L., & Dozois, D. J. (2014). Toward an integration of interpersonal risk models of depression and cognitive-behaviour therapy. Australian Psychologist, 49(6), 328–336.

Dozois, D. (2010). Understanding and enhancing the effects of homework in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(2), 157–161.

Ferreira, C., Guimarães, V., Santos, A., & Sousa, I. (2014). Gamification of stroke rehabilitation exercises using a smartphone. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare (pp. 282–285).

Ginsburg, G. S., Silverman, W. K., & Kurtines, W. K. (1995). Family involvement in treating children with phobic and anxiety disorders: A look ahead. Clinical Psychology Review, 15(5), 457–473.

Grills, A. E., DiBartolo, P. M., & Bowman, C. (2023). Psychoeducation: anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Handbook of child and adolescent psychology treatment modules, 59–73.

Higa-McMillan, C. K., Francis, S. E., Rith-Najarian, L., & Chorpita, B. F. (2016). Evidence base update: 50 years of research on treatment for child and adolescent anxiety. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45(2), 91–113.

Hofmann, S. G. (2013). The pursuit of happiness and its relationship to the meta-experience of emotions and culture. Australian Psychologist, 48(2), 94–97.

Hollis, C., Falconer, C. J., Martin, J. L., Whittington, C., Stockton, S., Glazebrook, C., & Davies, E. B. (2017). Annual research review: Digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems: A systematic and meta-review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(4), 474–503.

Hudson, J. L., & Kendall, P. C. (2002). Showing you can do it: Homework in therapy for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(5), 525–534.

Hughes, A. A., & Kendall, P. C. (2007). Prediction of cognitive behavior treatment outcome for children with anxiety disorders: Therapeutic relationship and homework compliance. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 35(4), 487–494.

Jacoby, R. J., & Abramowitz, J. S. (2016). Inhibitory learning approaches to exposure therapy: A critical review and translation to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 49, 28–40.

James, A. C., James, G., Cowdrey, F. A., Soler, A., & Choke, A. (2013). Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Wiley.

Jones, R. B., Stallard, P., Agha, S. S., Rice, S., Werner-Seidler, A., Stasiak, K., Kahn, J., Simpson, S. A., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Rice, F., Evans, R., & Merry, S. (2020). Practitioner review: Co-design of digital mental health technologies with children and young people. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(8), 928–940.

Kazantzis, N., & L’Abate, L. (2005). Theoretical foundations. In N. Kazantzis, F. P. Deane, K. R. Ronan, & L. L’Abate (Eds.), Using homework assignments in cognitive behavior therapy. Routledge.

Kazantzis, N., & Miller, A. R. (2022). A comprehensive model of homework in cognitive behavior therapy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 46(1), 247–257.

Kazantzis, N., Whittington, C., & Dattilio, F. (2010). Meta-analysis of homework effects in cognitive and behavioral therapy: A replication and extension. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(2), 144.

Kazantzis, N., Whittington, C., Zelencich, L., Kyrios, M., Norton, P. J., & Hofmann, S. G. (2016). Quantity and quality of homework compliance: A meta-analysis of relations with outcome in cognitive behavior therapy. Behavior Therapy, 47(5), 755–772.

Kazdin, A. E. (2018). Child psychotherapy research: Issues and opportunities. Developmental Science and Psychoanalysis (pp. 193–223). Routledge.

Khanna, M. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2008). Computer-assisted CBT for child anxiety: The coping cat CD-ROM. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 15, 159–165.

Khanna, M. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2010). Computer-assisted cognitive behavioral therapy for child anxiety: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 737.

Kelly, P. J., & Deane, F. P. (2011). Improving therapeutic use of homework: Suggestions from mental health clinicians. Journal of Mental Health, 20(5), 456–463.

Kendall, P. C., & Hedtke, K. A. (2006a). Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for Anxious Children: Therapist Manual (3rd ed.). Workbook Publishing.

Kendall, P. C., & Hedtke, K. A. (2006b). The Coping Cat Workbook (2nd ed.). Workbook Publishing.

Kendall, P. C., Kane, M., Howard, B., & Siqueland, L. (1990). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious children: Treatment manual. Department of Psychology, Temple University.

Kendall, P. C., Robin, J. A., Hedtke, K. A., Suveg, C., Flannery-Schroeder, E., & Gosch, E. (2005). Considering CBT with anxious youth? Think Exposures. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 12(1), 136–148.

Kendall, P. C., & Treadwell, K. R. (2007). The role of self-statements as a mediator in treatment for youth with anxiety disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(3), 380.

King, N. J., Hamilton, D. I., & Ollendick, T. H. (1988). Children’s phobias: A behavioural perspective. Wiley.

Klein, A. M., Hagen, A., Rahemenia, J., de Gier, E., Rapee, R. M., Nauta, M., de Bruin, E., Biesters, J., van Rijswijk, L., Bexkens, A., Baartmans, J. M. D., Mobach, L., Zimmermann, R., Krause, K., Bögels, S. M., Ollendick, T. H., & Schneider S. (2023). Combining one-session treatment with app-based technology to enhance the treatment of childhood specific phobias: A study protocol of a multicenter pragmatic randomized controlled trial.

LeBeau, R. T., Davies, C. D., Culver, N. C., & Craske, M. G. (2013). Homework compliance counts in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 42(3), 171–179.

Lebowitz, E. R., Panza, K. E., & Bloch, M. H. (2016). Family accommodation in obsessive-compulsive and anxiety disorders: A five-year update. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 16(1), 45–53.

Lee, P., Zehgeer, A., Ginsburg, G. S., McCracken, J., Keeton, C., Kendall, P. C., Birmaher, B., Sakolsky, D., Walkup, J., Peris, T., Albano, A. M., & Compton, S. (2019). Child and adolescent adherence with cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety: Predictors and associations with outcomes. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(sup1), S215–S226.

Levy, H. C., Stevens, K. T., & Tolin, D. F. (2022). Research Review: A meta-analysis of relapse rates in cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders in youth. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(3), 252–260.

Lieb, R., Miché, M., Gloster, A. T., Beesdo-Baum, K., Meyer, A. H., & Wittchen, H. U. (2016). Impact of specific phobia on the risk of onset of mental disorders: A 10-year prospective-longitudinal community study of adolescents and young adults. Depression and Anxiety, 33(7), 667–675.

Lundkvist-Houndoumadi, I., Thastum, M., & Nielsen, K. (2016). Parents’ difficulties as co-therapists in CBT among non-responding youths with anxiety disorders: Parent and therapist experiences. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 21(3), 477–490.

Lyneham, H. J., & Rapee, R. M. (2006). Evaluation of therapist-supported parent-implemented CBT for anxiety disorders in rural children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(9), 1287–1300.

Manassis, K., Lee, T. C., Bennett, K., Zhao, X. Y., Mendlowitz, S., Duda, S., Saini, M., Wilansky, P., Baer, S., Barrett, P., Bodden, D., Cobham, V. E., Dadds, M. R., Flannery-Schroeder, E., Ginsburg, G., Heyne, D., Hudson, J. L., Kendall, P. C., Liber, J., & Wood, J. J. (2014). Types of parental involvement in CBT with anxious youth: A preliminary meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(6), 1163.

Marks, I., & Cavanagh, K. (2009). Computer-aided psychological treatments: Evolving issues. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 5, 121–141.