Abstract

Background

The environments where parents spend time, such as at work, at their child’s school, or with friends and family, may exert a greater influence on their parenting behaviors than the residential neighborhoods where they live. These environments, termed activity spaces, provide individualized information about the where parents go, offering a more detailed understanding of the environmental risks and resources to which parents are exposed.

Objective

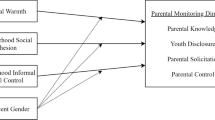

This study conducts a preliminary examination of how neighborhood context, social processes, and individual activity spaces are related to a variety of parenting practices.

Methods

Data were collected from 42 parents via door-to-door surveys in one neighborhood area. Survey participants provided information about punitive and non-punitive parenting practices, the locations where they conducted daily living activities, social supports, and neighborhood social processes. OLS regression procedures were used to examine covariates related to the size of parent activity spaces. Negative binomial models assessed how activity spaces were related to four punitive and five non-punitive parenting practices.

Results

With regards to size of parents’ activity spaces, male caregivers and those with a local (within neighborhood) primary support member had larger activity spaces. Size of a parent’s activity space is negatively related to use of punitive parenting, but generally not related to non-punitive parenting behaviors.

Conclusions

These findings suggest social workers should assess where parents spend their time and get socially isolated parents involved in activities that could result in less use of punitive parenting.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Brauer, F., & Castillo-Chávez, C. (2001). Mathematical models in population biology and epidemiology. New York: Springer.

Browning, C. R., & Soller, B. (2014). Moving beyond neighborhood: Activity spaces and ecological networks as contexts for youth development. Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research, 16(1), 165–196.

Burton, L. M., & Jarrett, R. L. (2000). In the mix, yet on the margins: The place of families in urban neighborhood and child development research. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1114–1135.

Chung, H. L., & Steinberg, L. (2006). Relations between neighborhood factors, parenting behaviors, peer deviance, and delinquency among serious juvenile offenders. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 319–331.

Cohen, S., Mermelstein, R., Kamarack, T., & Hoberman, H. (1985). Measuring the functional components of social support. In I. G. Sarason & B. R. Sarason (Eds.), Social support: Theory, research, and application (pp. 73–94). Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff.

Coiera, E. (2013). Social networks, social media, and social diseases. BMJ, 346, f3007.

Coohey, C. (2007). Social networks, informal child care, and inadequate supervision by mothers. Child Welfare, 68(6), 53–66.

Coulton, C., Crampton, D., Irwin, M., Spilbury, J., & Korbin, J. (2007). How neighborhoods influence child maltreatment: A review of the literature and alternative pathways. Child Abuse and Neglect, 31, 1117–1142.

Coulton, C., Korbin, J., & Su, M. (1999). Neighborhoods and child maltreatment: A multi-level study. Child Abuse and Neglect, 23(11), 1019–1040.

Crawford, T., Jilcott Pitts, S., McGuirt, J., Keyserling, T., & Ammerman, A. (2014). Conceptualizing and comparing neighborhood and activity space measures for food environment research. Health and Place, 30, 215–225.

Cuellar, J., Jones, D. J., & Sterrett, E. (2015). Examining parenting in the neighborhood context: A review. Journal of Child and Family Studies,. doi:10.1007/s10826-013-9826-y.

Dorsey, S., & Forehand, R. (2003). The relation of social capital to child psychosocial adjustment difficulties: The role of positive parenting and neighborhood dangerousness. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 25(1), 11–23.

El-Sayed, A. M., Scarborough, P., Seemann, L., & Galea, S. (2012). Social network analysis and agent-based modeling in social epidemiology. Epidemiologic Perspectives & Innovations, 9, 1–9.

Emery, C., Nguyen, H., & Kim, J. (2014). Understanding child maltreatment in Hanoi: Intimate partner violence, low self-control, and social and child care support. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29, 1228–1257. doi:10.1177/0886260513506276.

Freisthler, B., & Gruenewald, P. J. (2013). Where the individual meets the ecological: A study of parent drinking patterns, alcohol outlets and child physical abuse. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 27(6), 993–1000.

Freisthler, B., Holmes, M. R., & Price Wolf, J. (2014). The dark side of social support: Understanding the role of social support, drinking behaviors and alcohol outlets for child physical abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect, 38, 1106–1119. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.03.011.

Freisthler, B., & Maguire-Jack, K. (2015). Understanding the interplay between neighborhood structural factors, social processes, and alcohol outlets on child physical abuse. Child Maltreatment (in press).

Gaudin, J. M., Wodarski, J. S., Arkinson, M. K., & Avery, L. S. (1990). Remedying child neglect: Effectiveness of social network interventions. Journal of Applied Social Sciences, 15(1), 97–123.

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 1360–1380.

Guterman, N. B., Lee, S. J., Taylor, C. A., & Rathouz, P. (2009). Pa-rental perceptions of neighborhood processes, stress, personal control, and risk for physical child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse and Neglect, 33(12), 897–906.

Hoffman, M. L. (1983). Affective and cognitive processes in moral internalization. In E. T. Higgins, D. N. Ruble, & W. W. Hartup (Eds.), Social cognition and social development: A sociocultural perspective (pp. 236–274). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Inagami, S., Cohen, D. A., & Finch, B. K. (2007). Non-residential neighborhood exposures suppress neighborhood effects on self-rated health. Social Science and Medicine, 65, 1779–1791.

Jones, M., & Pebley, A. R. (2014). Redefining neighborhoods using common destinations: Social characteristics of activity spaces and home Census tracts compared. Demography, 51, 727–752.

Kamruzzaman, M., & Hine, J. (2012). Analysis of rural activity spaces and transport disadvantage using a multi-method approach. Transport Policy, 19, 105–120.

Kermack, W. O., & McKendrick, A. G. (1927). A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 115, 700–721. doi:10.1098/rspa.1927.0118.JSTOR94815.

Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 309–337.

Limber, S. P., & Hashima, P. Y. (2002). The social context: What comes naturally in child protection. In G. B. Melton, R. A. Thompson, & M. A. Small (Eds.), Toward a child-centered, neighborhood-based child protection system: A report of the consortium on children, families, and the law (pp. 41–66). Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group.

Matthews, S. A. (2011). Spatial polygamy and the heterogeneity of place: Studying people and place via geocentric methods. In L. M. Burton, S. P. Kemp, M. Leung, S. A. Matthews, & D. T. Takeuchi (Eds.), Communities, neighborhoods, and health: Expanding the boundaries of place (Vol. 1, pp. 35–55). New York, NY: Springer.

Molnar, B. E., Buka, S. L., Brennan, R. T., Holton, J. K., & Earls, F. (2003). A multi-level study of neighborhoods and parent-to-child physical aggression: Results from the project on human development in Chicago neighborhoods. Child Maltreatment, 8, 84–97.

Noach, E. (2011). Are rural women mobility deprived? A case study from Scotland. Sociologia Ruralis, 51(11), 79–97.

Oates, R. K., Davis, A. A., Ryan, M. G., & Stewart, L. F. (1979). Risk factors associated with child abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect, 3, 547–553.

Parker, K., & Wang, W. (2013). Modern parenthood: Roles of moms and dads converge as they balance work and family. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Sampson, R. J., Morenoff, J. D., & Earls, F. (1999). Beyond social capital: Spatial dynamics of collective efficacy for children. American Sociological Review, 64, 633–660.

Sastry, N., Pebley, A. R., & Zonta, M. (2002). Neighborhood definitions and the spatial dimension of daily life in Los Angeles (CCPRWorking Paper 033-04). Los Angeles: California Center for Population Research, University of California–Los Angeles.

Straus, M. A. & Fauchier, A. (2011). Manual for the dimensions of discipline inventory (DDI). Durham, NH: Family Research Laboratory, University of New Hampshire. http://pubpages.unh.edu/~mas2/

Thompson, R. A. (2014). Social support and child protection: Lessons learned and learning. Child Abuse and Neglect,. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.06.011.

Van Leeuwen, K. G., Fauchier, A., & Straus, M. A. (2012). Assessing dimensions of parental discipline. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 34(2), 216–231. doi:10.1007/s10862-012-9278-5.

Whipple, E. E., & Richey, C. A. (1997). Crossing the line from physical discipline to child abuse: How much is too much? Child Abuse and Neglect, 21(5), 431–444. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(97),00004-5.

Widom, C. S. (1989). Does violence beget violence? A critical examination of the literature. Psychological Bulletin, 106(1), 3. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.106.1.3.

Wolock, I., & Magura, S. (1996). Parental substance abuse as a predictor of child maltreatment re-reports. Child Abuse and Neglect, 20, 1183–1193.

Funding

This project was supported by Grant Number P60-AA-006282 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and a faculty fellowship from the John Randolph and Dora Haynes Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism or the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical standard

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Freisthler, B., Thomas, C.A., Curry, S.R. et al. An Alternative to Residential Neighborhoods: An Exploratory Study of How Activity Spaces and Perception of Neighborhood Social Processes Relate to Maladaptive Parenting. Child Youth Care Forum 45, 259–277 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-015-9329-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-015-9329-7