Abstract

Purpose

The myocardium is largely dependent upon oxidation of fatty acids for the production of ATP. Cardiac contractile abnormalities and failure have been reported after acute emotional stress and there is evidence that catecholamines are responsible for acute stress-induced heart injury. We hypothesized that carnitine deficiency increases the risk of stress-induced heart injury.

Methods

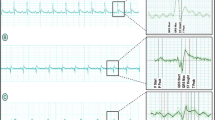

Carnitine deficiency was induced in Wistar rats by adding 20 mmol/L of sodium pivalate to drinking water (P). Controls (C) received equimolar sodium bicarbonate and a third group (P + Cn) received pivalate along with 40 mmol/L carnitine. After 15 days, 6 rats/group were used to evaluate function of isolated hearts under infusion of 0.1 μM isoproterenol and 20 rats/group were submitted to a single subcutaneous administration of 50 mg/kg isoproterenol.

Results

Isoproterenol infusion in C markedly increased the heart rate, left ventricular (LV) systolic pressure and coronary flow rate. In P rats, isoproterenol increased the heart rate and LV systolic pressure but these increases were not paralleled by a rise in the coronary flow rate and LV diastolic pressure progressively increased. Subcutaneous isoproterenol induced 15 % mortality rate in C and 50 % in P (p < 0.05). Hearts of surviving P rats examined 15 days later appeared clearly dilated, presented a marked impairment of LV function and a greater increase in tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) levels. All these detrimental effects were negligible in P + Cn rats.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that carnitine deficiency exposes the heart to a greater risk of injury when sympathetic nerve activity is greatly stimulated, for example during emotional, mental or physical stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rebouche CJ. Carnitine function and requirements during life cycle. Faseb j. 1992;6:3379–86.

Pons R, De Vivo DC. Primary and secondary carnitine deficiency syndromes. J Child Neurol. 1995;10:S8–S24.

Longo N, Amat di San Filippo C, Pasquali M. Disorders of carnitine transport and the carnitine cycle. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2006;142:77–85.

Magoulas PL, El-Hattab AW. Systemic primary carnitine deficiency: an overview of clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:68.

Evans AM, Fornasini G. Pharmacokinetics of L-carnitine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:941–67.

Brass EP. Pivalate-generating prodrugs and carnitine homeostasis in man. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:589–98.

Jia YY, Lu CT, Feng J, et al. Impact on L-carnitine homeostasis of short-term treatment with the pivalate prodrug tenofovir dipivoxil. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;113:431–5.

Boemer F, Schoos R, de Halleux V, Kalenga M, Debray FG. Surprising causes of C5-carnitine false positive results in newborn screening. Mol Genet Metab. 2014;111:52–4.

Ricciolini R, Scalibastri M, Carminati P, Arduini A. The effect of pivalate treatment of pregnant rats on body mass and insulin levels in the adult offspring. Life Sci. 2001;69:1733–8.

Broderick TL. Hypocarnitinaemia induced by sodium pivalate in the rat is associated with left ventricular dysfunction and impaired energy metabolism. Drugs R&D. 2006;7:153–61.

Rasmussen J, Nielsen OW, Lund AM, Køber L, Djurhuus H. Primary carnitine deficiency and pivalic acid exposure causing encephalopathy and fatal cardiac events. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36:35–41.

Cebelin M, Hirsch CS. Human stress cardiomyopathy. Hum Pathol. 1980;11:123–32.

Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JAC, et al. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:539–48.

Martin AS. The brain–heart connection. Circulation. 2007;116:77–84.

Templin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:929–38.

Analóczy Z Role of catecholamines in stress-induced heart disease. In: Beamish RE, Panagia V, Dhalla NS, editors. Pathogenesis of stress-induced heart disease. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff; 1985. p. 213–27.

Downing SE, Chen V. Myocardial injury following endogenous catecholamine release in rabbits. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1985;17:377–87.

Rona G Involvement of catecholamines in the development of myocardial cell damage. In: Beamish RE, Panagia V, Dhalla NS, editors. Pathogenesis of stress-induced heart disease. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff; 1985. p. 228–36.

Arakawa H, Kodama H, Matsuoka N, Yamaguchi I. Stress increases plasma enzyme activities in rats: differential effects of adrenergic and cholinergic blockades. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:1296–303.

Willis BC, Salazar-Cantú A, Silva-Platas C, et al. Impaired oxidative metabolism and calcium mishandling underlie cardiac dysfunction in a rat model of post-acute isoproterenol-induced cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;308:H467–77.

Costoli T, Bartolomucci A, Graiani G, Stilli D, Laviola G, Sgoifo A. Effects of chronic psycho-social stress on cardiac autonomic responsiveness and myocardial structure in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H2133–40.

Bianchi PB, Davis AT. Sodium pivalate treatment reduces tissue carnitines and enhances ketosis in rats. J Nutr. 1991;121:2029–36.

Bergmeyer HU. Methoden der enzymatischen analyse. Verlag Chemie: Weinheim; 1974.

Pace JA, Wannemacher RW, Neufeld HA Improved radiochemical assay for carnitine and its derivatives in plasma and tissue extracts. Clin Chem. 1978;24:32–5.

Ramesh CV, Malarvannan P, Jayakumar R, Jayasundar S, Puvanakrishnan R. Effect of a novel tetrapeptide derivative in a rat model of isoproterenol induced myocardial necrosis. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;187:173–82.

Rasmussen J, Thomsen JA, Olesen JH, Lund TM, Mohr M, Clementsen J, Nielsen OW, Lund AM. Carnitine levels in skeletal muscle, blood, and urine in patients with primary carnitine deficiency during intermission of L-carnitine supplementation. JIMD Rep. 2015;20:103–11.

Lopaschuk GD, Ussher JR, Folmes CD, Jaswal JS, Stanley WC. Myocardial fatty acid metabolism in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:207–58.

Dennis SC, Gevers W, Opie LH. Protons in ischemia: where do they come from; where do they go to? J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1991;23:1077–86.

Liu Q, Docherty JC, Rendell JC, Clanachan AS, Lopaschuk GD. High levels of fatty acids delay the recovery of intracellular pH and cardiac efficiency in post-ischemic hearts by inhibiting glucose oxidation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:718–25.

Hool LC. What cardiologists should know about calcium ion channels and their regulation by reactive oxygen species. Heart Lung Circ. 2007;16:361–72.

Garcia-Dorado D, Ruiz-Meana M, Inserte J, Rodriguez-Sinovas A, Piper HM. Calcium-mediated cell death during myocardial reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;94:168–80.

Betgem RP, de Waard GA, Nijveldt R, Beek AM, Escaned J, van Royen N. Intramyocardial haemorrhage after acute myocardial infarction. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12:156–67.

Burnstock G, Ralevic V. Purinergic signaling and blood vessels in health and disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;66:102–92.

Broderick TM, Christos SC, Wolf BA, et al. Fatty acid oxidation and cardiac function in the sodium pivalate model of secondary carnitine deficiency. Metabolism. 1995;44:499–505.

Sushamakumari S, Jayadeep A, Kumar JS, Menon VP. Effect of carnitine on malondialdehyde, taurine and glutathione levels in heart of rats subjected to myocardial stress by isoproterenol. Indian J Exp Biol. 1989;27:134–7.

Mathew S, Menon PV, Kurup PA. Effect of administration of carnitine on the severity of myocardial infarction induced by isoproterenol in rats. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1986;64:79–87.

Morris GS, Zhou Q, Wolf BA, et al. Sodium pivalate reduces cardiac carnitine content and increases glucose oxidation without affecting cardiac functional capacity. Life Sci. 1995;57:2237–44.

Takahashi R, Asai T, Murakami H, et al. Pressure overload-induced cardiomyopathy in heterozygous carrier mice of carnitine transporter gene mutation. Hypertension. 2007;50:497–502.

Kuwajima M, Lu K, Sei M, et al. Characteristics of cardiac hypertrophy in the juvenile visceral steatosis mouse with systemic carnitine deficiency. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:773–81.

Lahjouji K, Elimrani I, Wu J, Mitchell GA, Qureshi IA. A heterozygote phenotype is present in the jvs +/− mutant mouse livers. Mol Genet Metab. 2002;76:76–80.

Koizumi A, Nozaki J, Ohura T, et al. Genetic epidemiology of the carnitine transporter OCTN2 gene in a Japanese population and phenotypic characterization in Japanese pedigrees with primary systemic carnitine deficiency. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2247–54.

Amat di San Filippo C, MR T, Mestroni L, LD B, Longo N. Cardiomyopathy and carnitine deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;94:162–6.

Scaglia F, Wang Y, Singh RH, et al. Defective urinary carnitine transport in heterozygotes for primary carnitine deficiency. Genet Med. 1998;1:34–9.

Di Liberato L, Arduini A, Rossi C, Di Castelnuovo A, et al. L-Carnitine status in end-stage renal disease patients on automated peritoneal dialysis. J Nephrol. 2014;27:699–706.

Converse Jr RL, Jacobsen TN, Toto RD, et al. Sympathetic overactivity in patients with chronic renal failure. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1912–8.

Abrahamsson K, Mellander M, Eriksson BO, et al. Transient reduction of human left ventricular mass in carnitine depletion induced by antibiotics containing pivalic acid. Br Heart J. 1995;74:656–9.

Burke AP, Virmani R. Pathophysiology of acute myocardial infarction. Med Clin North Am. 2007;91:553–72.

Willerson JT, Ridker PM Inflammation as a cardiovascular risk factor. Circulation. 2004;109:II2–II10.

Gasparyan AY Cardiovascular risk and inflammation: pathophysiological mechanisms, drug design, and targets. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:1447–9.

Lee BJ, Lin JS, Lin YC, Lin PT. Antiinflammatory effects of L-carnitine supplementation (1000 mg/d) in coronary artery disease patients. Nutrition. 2015;31:475–9.

Vescovo G, Ravara B, Gobbo V, et al. L-carnitine: a potential treatment for blocking apoptosis and preventing skeletal muscle myopathy in heart failure. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;283:C802–10.

Jiang F, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Wu J, Yu L, Liu S. L-carnitine ameliorates the liver inflammatory response by regulating carnitine palmitoyltransferase I-dependent PPARγ signaling. Mol Med Rep 2015

Hua X, Su Z, Deng R, Lin J, Li DQ, Pflugfelder SC. Effects of L-carnitine, erythritol and betaine on pro-inflammatory markers in primary human corneal epithelial cells exposed to hyperosmotic stress. Curr Eye Res. 2015;40:657–67.

Ussher JR, Wang W, Gandhi M, Keung W, et al. Stimulation of glucose oxidation protects against acute myocardial infarction and reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;94:359–69.

Heusch G, Libby P, Gersh B, et al. Cardiovascular remodelling in coronary artery disease and heart failure. Lancet. 2014;383:1933–43.

Arduini A, Bonomini M, Savica V, Amato A, Zammit V. Carnitine in metabolic disease: potential for pharmacological intervention. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;120:149–56.

Acknowledgments

This work was in part supported by funds from: Programma Operativo Nazionale [01_00937] - MIUR “Modelli sperimentali biotecnologici integrati per lo sviluppo e la selezione di molecole di interesse per la salute dell’uomo”. The authors are gratefull Daniela Heuberger for the excellent technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

There are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication for Prof. Mario Bonomini. Dr. Pietro Lo Giudice and Dr. Arduino Arduini confirm that they are employees of Sigma Tau Pharmaceuticals and CoreQuest Sagl, respectively.

Ethical Approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giudice, P.L., Bonomini, M. & Arduini, A. A Moderate Carnitine Deficiency Exacerbates Isoproterenol-Induced Myocardial Injury in Rats. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 30, 119–127 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-016-6647-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-016-6647-4