Abstract

Background

ACE inhibition results in secondary prevention of coronary artery disease (CAD) through different mechanisms including improvement of endothelial dysfunction. The Perindopril-Function of the Endothelium in Coronary artery disease Trial (PERFECT) evaluated whether long-term administration of perindopril improves endothelial dysfunction.

Methods

PERFECT is a 3-year double blind randomised placebo controlled trial to determine the effect of perindopril 8 mg once daily on brachial artery endothelial function in patients with stable CAD without clinical heart failure. Endothelial function in response to ischaemia was assessed using ultrasound. Primary endpoint was difference in flow-mediated vasodilatation (FMD) assessed at 36 months.

Results

In 20 centers, 333 patients randomly received perindopril or matching placebo. Ischemia-induced FMD was 2.7% (SD 2.6). In the perindopril group FMD went from 2.6% at baseline to 3.3% at 36 months and in the placebo group from 2.8 to 3.0%. Change in FMD after 36 month treatment was 0.55% (95% confidence interval −0.36, 1.47; p = 0.23) higher in perindopril than in placebo group. The rate of change in FMD per 6 months was 0.14% (SE 0.05, p = 0.02) in perindopril and 0.02% (SE 0.05, p = 0.74) in placebo group (0.12% difference in rate of change p = 0.07).

Conclusion

Perindopril resulted in a modest, albeit not statistically significant, improvement in FMD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

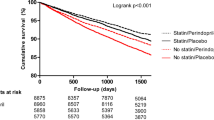

ACE inhibition has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality among a variety of patients, i.e. patients with congestive heart failure,[1–3], survivors of a myocardial infarction [4, 5], a-symptomatic patients with left ventricular dysfunction [6, 7], patients with acute myocardial infarction [8–11], post-myocardial infarction patients [6, 7, 12–14] and older high risk patients with documented coronary heart disease without heart failure and, in some, no left ventricular dysfunction [15]. Recently, the EUROPA trial expanded the evidence by showing that ACE inhibition reduces cardiovascular event risk by 20% among a relatively low risk population of patients with stable coronary heart disease without apparent heart failure [16]. In contrast, the PEACE trial study did not show a benefit of ACE inhibition over placebo [17].

Several mechanisms may explain the beneficial effects of ACE inhibition on morbidity and mortality [18]. One of them is the effect of ACE inhibition on shifting the balance between vasoconstrictive forces (angiotensin II) and vasodilatative forces (bradykinin and nitric oxide) towards vasodilatation [18]. Also, ACE inhibition may protect against endothelial apoptosis. These mechanisms lead to an improvement in endothelial dysfunction. The PERFECT study, as a sub-study to the EUROPA trial, was designed to verify the above mentioned pathophysiologic concept [19]. In the PERFECT study, B-mode ultrasonography of the brachial artery was be used to assess endothelial function in response to ischaemia (reactive hyperaemia) as measured by flow mediated vasodilatation (FMD).

The present paper describes the main findings of the PERFECT study.

2 Methods

2.1 Design

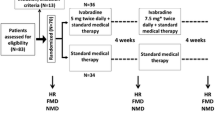

The rationale and design of the PERFECT study has been detailed elsewhere [19]. In short, the PERFECT study is a study nested within the EUROPA trial. The EUROPA trial is a three year double-blind, multi-centre, placebo-controlled randomised study that aims at studying the effect of the ACE-inhibitor perindopril on morbidity and mortality in over 12,000 patients with stable coronary artery disease without clinical heart failure [16]. The PERFECT study was designed as a parallel group randomised placebo controlled trial to determine the effect of perindopril (8 mg/day) on brachial artery endothelial function, as assessed by FMD.

After a run-in period of 4 weeks with 4 mg/day perindopril, participants were randomised to perindopril or placebo. The recruitment for the PERFECT study started in May 1998. Both the EUROPA trial and the PERFECT study finished recruitment in June 1999. In the PERFECT study 333 patients were recruited in 20 European centers (8 in Czech Republic, 1 in Germany, 2 in Greece, 4 in Netherlands, 4 in Poland and 1 in Sweden). Endothelial function, measured as FMD was assessed at the baseline visit, just before the run-in period. Follow-up B mode ultrasound for FMD assessment were performed at 6, 12, 24 and 36 months after randomisation.

In addition, an endothelial independent vasodilatation test (NTG) using nitroglycerine sublingually, was performed at baseline and at 36 months after randomisation. The NTG measurements were performed without withholding of used medications.

2.2 Study population

The population enrolled in the PERFECT study is similar to that enrolled in the EUROPA trial [16]. In short, the main inclusion criteria are 18 years of age or above; documented coronary artery disease, not scheduled for re-vascularisation and informed consent obtained. Documented coronary heart disease includes a history of previous myocardial infarction (confirmed by ECG demonstrating Q waves in two contiguous leads and/or changes in cardiac enzymes more than or equal to twice the normal values) of at least 3 months prior to the selection visit, or, a history of PTCA or CABG of at least 6 months prior the selection visit, or, abnormal findings at coronary angiography (angiographical evidence of ≥70% narrowing of ≥1 major coronary artery according to visual analysis). Also, men with a history of chest pain documented by either a positive exercise test or by the development of regional wall motion abnormalities during stress echocardiography or nuclear scintigraphy or perfusion defects during scintigraphy perfusion imaging could be included.

The main exclusion criteria were clinical signs of heart failure requiring treatment; systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg; uncontrolled treated hypertension with systolic blood pressure >180 mmHg and/or a diastolic blood pressure >100 mmHg; use of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor inhibitors within 1 month prior to the first selection visit; renal failure with serum creatinine >150 μmol/l; serum potassium >5.0 mmol/l; liver disease with liver enzymes >3 times upper normal values; a history of stroke or cerebral transient ischaemic attacks within the preceding 3 months and known intolerance to ACE inhibitors.

All patients who participated in the main EUROPA study and had been enrolled in study centres that participated in the PERFECT study, were additionally invited to participate in the PERFECT study. All those patients that were willing and gave informed consent were considered as PERFECT participants. Since refusal rates for PERFECT were assumed to be independent of the treatment assignment, it was expected that the PERFECT participants would resembles closely the EUROPA participants.

2.3 PERFECT study measurements

The study outcomes were (1) absolute change in FMD percentage of the brachial artery between the 36 month measurement and the baseline measurement, (2) absolute change in FMD percentage of the brachial artery between the 6 month measurement and the baseline measurement, (3) Rate of change in FMD in 36 months.

2.4 Assessment of brachial artery flow mediated vasodilatation (FMD)

Preceding the start of the PERFECT study, a detailed training programme was implemented to ensure standardisation of the FMD measurements across all centers. Based on the performance during and after the training programme all sonographers entered the certification procedure.

Ultrasound examinations were performed using a Duplex scanner with a >7 MHz or 7–10 MHz linear array transducer, with on line ECG recording. The examinations were recorded on (S-)VHS videocassette and sent to a core laboratory for off line reading. The details of the measurement have been detailed elsewhere [19]. In short, patients were studied in supine position. Three ECG leads were attached. The arm was placed in a specifically developed splint to reduce arm movements during the procedure as much as possible and to allow for fixation of the ultrasound transducer. The blood pressure cuff was placed just below the elbow, and below the ultrasound transducer. After a 10 min rest, the brachial artery at the elbow was visualised using a ultrasound machine with a >7 MHz or 5–10 MHz linear array transducer. When a satisfactory longitudinal optimal image of the brachial artery was obtained, the position of the transducer was fixed in the holder. Three B-mode images showing the lumen diameter were frozen on the R-wave of the ECG to provide information for off-line measurement of the ‘baseline’ lumen diameter for the ischemia test. Then the blood pressure cuff was inflated to suprasystolic levels (50 mmHg above) for a four-minute period. During that time the sonographer checked whether the optimal image was steady. After deflation of the blood pressure cuff, ultrasound examination continued for 5 min. Every 15 s a B-mode image was frozen on the R-wave of the ECG (end-diastole) for off-line lumen diameter measurements [20, 21].

At baseline and at month 36 the effect of nitroglycerine was evaluated after the ischemia test using a similar procedure as described above. When a satisfactory longitudinal optimal image of the brachial artery was obtained, three B-mode images showing the lumen diameter were frozen on the R-wave of the ECG to provide information for off-line measurement of the ‘baseline’ lumen diameter for the nitroglycerine test. Then 400 μg of nitroglycerine were sublingually administered. The ultrasound examination continued for another 5 min. Every 15 s a B-mode image was frozen on the R-wave of the ECG (end-diastole) for off-line lumen diameter measurements.

The off line reading of the PERFECT Study ultrasound examinations was done using Brachial Tools®, version 3.2.6 (Medical Imaging Applications, Iowa, USA). In short, first the frozen images on videotape are digitised and put into a time sequence. Then the reader manually identifies the part of the brachial artery in which the boundaries are good and stable visualised in all these images. Next, the Brachial Tools® software detects the boundaries through all these images and provides numerical data on lumen diameters of all the images. The diameter at baseline was based on the average of the three frozen images. FMD was estimated as [maximal lumen diameter after ischemia − diameter at baseline]/diameter at baseline. The nitroglycerine response (flow independent vasodilatation) was estimated as [maximal lumen diameter after nitroglycerine − diameter at baseline]/diameter at baseline.

2.5 Sample size considerations

At the start of the preparations of the PERFECT study in 1998, an estimate of what was considered a clinically relevant difference in FMD from baseline varied between 1.8 and 6.7% in the published literature. In a study among subjects who underwent coronary angiography, the positive predictive value of FMD less than 3% in predicting coronary endothelial dysfunction was 95% [22]. It had been argued that in clinical trials the number of subjects needed should be such that at least a 2% difference in FMD is detectable [23]. In an earlier study performed by our group, among 32 healthy volunteers the mean FMD was 7.7% (SD 5.0) [24]. Since the present study is a multi-centre which generally increases the variability in the FMD measurements compared to single-centre studies, the sample size calculation is to be considered conservative.

With a 90% power, a two-sided alpha of 5%, an absolute difference in FMD of 2.0% can be assessed with a sample size of 131 subjects in each arm of the trial. With an anticipated 10% drop-out rate in the EUROPA trial, a total of 288 subjects needed to be randomised.

2.6 Data analysis

General characteristics of the study population were given according to the intention to treat principle (ITT). The ITT population comprised patients who had a 6 month FMD measurement for the analyses on 6 month change in FMD. For 36 month change the ITT population comprised patients with 36 month FMD data. For the rate of change analyses, the ITT population comprised of all those patients who had at least one 6 month baseline FMD value. Those patients who had no follow-up FMD measurements or those who had inadequate measurements were excluded for the statistical analyses. Absence to compliance of treatment was not a reasons to exclude patients from the analyses.

For each patient the difference in FMD at 6 month and baseline was calculated (FMD value at 6 months − FMD value at baseline). A similar approach was used for 36 month difference in FMD. Next, linear regression analyses were applied to study whether the 6 month or 36 month differences in FMD differed between treatment groups using difference in FMD as dependent variable and treatment assignment as independent variable. No adjustments were additionally made since the treatment assignment was achieved using a randomisation procedure. These analyses were carried out using SPSS statistical package (version 12.0). This analytic approach had a priori been decided upon although we recognise that for the 36 month effects the reduction in sample size due to the absence of 36 month measurements could be considerable.

To evaluate differences in rate of change of FMD between treatment groups a random effects model was applied using SAS statistical software (version 8.1). Apart from the assumption that the change in FMD is linear over time, we made no assumptions for the intercept (random) of the model and for correlation structure (unstructured) between repeated FMD measurements. The primary model FMD percentage as outcome, and had as independent variables assigned treatment group, visit time from baseline, and the interaction term time × group assignment. Rate of change was estimated per 6 month intervals. The advantage of using a random effects model above the earlier mentioned analytic approaches is that all FMD measurements that have been performed during the study will be used in the analyses and thereby increasing the power.

Although this is a randomised controlled trial and therefore in principle adjustment for other variables is not needed, we did perform analyses where adjustments were made for study center and for those factors that were imbalanced at baseline (gender, chest pain, hypertension).

Reproducibility of the FMD measurement was assessed using the information of the FMD measurement at baseline and at the 6 month visit in the placebo group. Overall reproducibility, i.e., reflecting the combined variability due to between and within sonographer, and between and within reader and between visit aspects, was evaluated using Intraclass correlation coefficient.

3 Results

The general characteristics of the 333 randomised participants are given in Table 1. Overall the characteristics, including the brachial artery measurements were well balanced between treatment groups except for some factors. The perindopril group comprised more men and more patients with a history of hypertension. In contrast, chest pain was less common. Out of these 333 subjects information on FMD was considered too poor in 20 subjects to be evaluated in the study. These subjects (9 in the perindopril group) were therefore not used in the further analyses with FMD. Figure 1 depicts the distribution of the FMD measurements at baseline (top) and the nitroglycerine response measurements (bottom) among the participants. Follow-up measurement of FMD at 6 month visit, 12 month visit, 24 months and 36 month visits were done in 325, 324, 319, and 301 patients, respectively. Of those, the FMD scans indicated of sufficient quality were 310, 292, 293 and 268, respectively. For NTG measurements at baseline and end of study these figures were 330, 286, 304 and 258, respectively. Data on the reproducibility of the FMD measurement was based on 145 repeat scans within a 6 month time frame, and combined the effects of variance due to the assessment (technical and biological) and due to the offline measurement. The latter has been documented earlier [19], and showed an Intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.65 for the ischemia test. The overall reproducibility was moderate with an Intraclass correlation of 0.12 (p = 0.25). Restriction to centers with higher reproducibility findings did not materially affect the main findings, therefore results pertaining to all participants are presented.

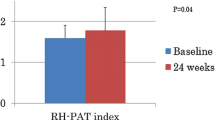

In Fig. 2 the FMD response over time is presented. An improvement is seen in the perindopril group, starting after 12 months, whereas in the placebo group the trend is towards no change over time.

The mean change in FMD between baseline and 36 months was 0.91% (SD 3.77) in the perindopril group and 0.35% (SD 3.63) in the placebo group. The change in FMD of the brachial artery between the 36 month measurement and the baseline measurement was 0.55 % (95% confidence interval −0.42 1.47; p value 0.23) higher in the perindopril group compared to placebo. This statistically non-significant difference constitutes a relative improvement in FMD of 20% (=0.55/2.74). This analysis was based on measurements available at both baseline and 36 month of 256 participants. Adjustment for center or for imbalances at baseline did not materially affect the magnitude, direction or significance of the intention-to-treat estimate.

The change in flow-mediated vasodilatation of the brachial artery between the 6 month measurement and the baseline measurement between treatment groups was −0.12% (95% CI −0.87, 0.85; p value 0.97). This analysis was based on measurements available at both baseline and 6 months of 294 participants. Adjustment for center or for imbalances at baseline did not materially affect the magnitude, direction or significance of the intention-to-treat estimate.

The rate of change in endothelial function per 6 months as estimated by a random effect model using data of all participants was 0.14% (SE 0.05, p = 0.02) in the perindopril group and 0.02% (SE 0.05, p = 0.74) in the placebo group (Fig. 3) The difference in rate of change in FMD between the treatment arms was 0.12% (p = 0.07). Adjustment for center or for imbalances at baseline did not materially affect the magnitude, direction or significance of the intention-to-treat estimate.

No difference in nitroglycerine response results at 36 months was found between perindopril and placebo. Mean values (SD) were 8.2% (5.4) and 8.8% (5.4), respectively.

4 Discussion

The PERFECT study was designed to evaluate whether long-term administration of perindopril improves endothelial dysfunction in patients with stable CAD and without clinical heart failure. Our findings, analysed in two ways, indicate that long-term use of perindopril is compatible with an improvement in FMD, although these findings were not statistically significant. The rate of change in endothelial function per 6 months showed a significant improvement over time in the perindopril group, where the comparison with placebo showed that these improvements bordered on statistical significance (p of 0.07).

The mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of ACE inhibition are complex, and include inhibition of angiotensin II production with, subsequently, a reduction of its negative effects on the vascular system. Through coupling to the angiotensin II type 1 receptor, angiotensin II leads to vasoconstriction, vascular inflammation with an increase in pro-inflammatory genes, adhesion molecules and macrophage recruitment, an increased uptake and oxidation of LDL by endothelial cells and oxyradical production leading to endothelial dysfunction. Furthermore, it stimulates sympathetic activation and aldosterone release, adding to vasoconstriction and endothelial dysfunction. ACE inhibitors may positively affect endothelial dysfunction by decreasing angiotensin II production alone. However, equally or possibly more important is their effect on bradykinin. Through coupling to the bradykinin B2 receptor bradykinin results in NO and endothelial-derived hyperpolarizing factor. In addition it promotes prostacyclin release. As a consequence, bradykinin is not only a strong vasodilator, it also inhibits, through NO production, vascular smooth muscle cell growth and migration, improves endothelial function, inhibits the expression of cell adhesion molecules, prevents platelet adhesion, and restores the fibrinolytic balance by tPA production. As such, bradykinin effectively counteracts the deleterious effects of angiotensin II. The improvement of endothelial function with ACE inhibition is bradykinin-dependent [25]. Of importance, not all ACE inhibitors increase bradykinin production to a similar extent. This depends, amongst other factors, on tissue affinity of the ACE inhibitor. Perindopril is one of the few ACE inhibitors with profound tissue affinity [26]. It increases bradykinin significantly more than enalapril despite similar effects on circulating angiotensin II [27]. Also, perindopril increases bradykinin levels at lower doses than needed to reduce angiotensin II levels [28]. Indirectly, the pivotal role of bradykinin on endothelial function is suggested by the observation that perindopril, but not an angiotensin receptor antagonist telmisartan, improves endothelium-dependent vasodilatation, after long-term treatment despite similar anti-hypertensive effects [29]. The PERTINENT study, another sub-study of EUROPA, provides further evidence in support for the improvement in endothelial function observed in the PERFECT study [50]. PERTINENT studied the effect of 8 mg perindopril versus placebo after one year treatment on plasma markers of atherosclerosis, neurohormonal activation and apoptosis. A significant reduction in angiotensin II and cytokine levels was found together with a reduction in apoptosis. Of importance, bradykinin increased significantly accompanied by an increase in ecNO synthase in perindopril but not in placebo treated patients. These data from a similar patient population as in PERFECT provide evidence that pivotal mechanisms in endothelial function are improved by perindopril treatment and could lead to an improvement in endothelial function, as indicated in PERFECT.

There have been several studies performed on the effect of ACE inhibition and endothelial function as measured by FMD of the brachial artery (Table 2) [30–42]. Most studies were single centre studies, had a limited number of subjects enrolled (varying from 9 to 46), and were of short duration (from postprandial effect to 6 months). The designs applied were mostly cross-over trials. Overall, the effects varied from beneficial effects on FMD response to no effect at all without consistency in patient groups. That severely limits direct comparison with our results. In PERFECT the first FMD measurement after randomisation was at 6 months. No difference in FMD was found at 6 months between treatment groups. Our study is unique in that we studied long term effects of intervention on FMD. A recent review of studies on the long term effect of ACE inhibition on endothelial function, as assessed by a variety of measurements (vascular response and/or plasma markers) concluded that for CAD patient results are consistently showing an improvement in endothelial function [43]. This is substantiated by the results from trials showing that coronary endothelial dysfunction improves after 6 months of treatment with ACE inhibitors [44].

Some aspects of the study need some consideration to appreciate the findings. Firstly, the initial sample size estimation was based on assumptions that came from cross-sectional studies, since longitudinal data were not available. When we perform a posterior power calculation based on the availability of 240 subjects using actually observed data on the difference between baseline and 36 months in FMD in the control arm (0.35% with a SD 3.63), we had a 80% power to detect a difference in change from baseline between the perindopril group and the placebo group of 1.3%, assuming a two sided alpha of 0.05. Our power to detect a 2% difference, as was originally proposed, was even higher. However, our power to detect the currently observed difference of 0.55% was only 20%, suggesting that we can not really exclude the fact that perindopril may have an effect on endothelial function. Secondly, it has been documented that the value of FMD measurement may be affected considerably by life style habits, such as recent physical activity, smoking, and food intake, technical aspects of the measurement, such as cuff location, and concomitant drug treatment, such as statins [45–48]. Furthermore, the reproducibility of the FMD measurement in situations where lifestyle factors were controlled optimally, may be moderate with coefficients of variation between 25–50%, indicating that within person variability may be considerable [49]. This in general leads to attenuation of the magnitude of the relations under study. Although in PERFECT a uniform training and FMD methodology was used, the study was a multicenter trial, which compared to single center studies generally increases variability as shown by our reproducibility findings. This was one of the reasons we applied a random effect model to increase the power of the study to detect meaningful differences between treatment arms.

The baseline FMD value in our population was low, similar to that found in other studies in CAD patients [48], and may indicate the presence of endothelial dysfunction in this group. The effect of ACE inhibition on FMD over time was modest, although significant. This may be partially attributed to the fact that most of our patients were using multiple drugs that improve endothelial function as well, for example statins [49]. This may have reduced our ability to demonstrate the full benefit of ACE inhibition per se.

In conclusion, appreciating the variability in the FMD measurement and the widespread use of other drugs that may affect FMD, our findings are compatible with the notion that the beneficial effects of perindopril on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the EUROPA study may be at least partly explained by an improvement in endothelial function.

Participating PERFECT centers

CZECH REPUBLIC: CESKY KRUMLOV: J. Florian, MD (principal investigator), V. Kuchar, MD; BRNO: B. Semrad, MD (principal investigator), J. Ziembova, MD, J. Schildberger, MD; PILSEN, H. Rosolova, MD (principal investigator), V. Jankovych, MD; PRAQUE: R. Spacek, MD (principal investigator), P. Stanka; PRAQUE: J. Hradec, MD (principal investigator), J. Malik, MD; TABOR: J. Charouzek, MD (principal investigator) V. Jirka, MD; PRAGUE: P. Jansky (principal investigator), Koelbel, MD; SLANY: G. Marcinek, MD (principal investigator), M. Votypka-Pecha; BRNO: L. Groh (principal investigator), I. Hofirek, L. Nechvatal. GERMANY: MUNICH: C. von Schacky, MD, PhD (principal investigator), S. Stoerk, MD, P. Markov. GREECE: ATHENS: Gialavos, MD, (principal investigator), A. Androulakis, MD; ATHENS: J. Lekakis, MD, C. Papamichael, MD. NETHERLANDS: HARDERWIJK: R. Dijkgraaf, MD (principal investigator), Y.Jansen-Timmer, H. Bralts; HENGELO: J.J.J. Bucx, MD (principal investigator until 01/01/2000), H. Droste, MD (principal investigator from 01/01/2000), G. Assink; EMMEN: L.F.M. van de Merkhof, MD (principal investigator), R. Vinke; ROTTERDAM: van Nierop, MD (principal investigator), I.M. Toonder, E. Korten. POLAND: KRAKOW: A.Gackkowski, MD (principal investigator); KRAKOW: T. Zielinsky, MD (principal investigator), T. Rywik, MD; KATOWICE: A.M. Wnuk-Wonjar, MD (principal investigator), C. Vita; KATOWICE: M. Tendera, MD (principal investigator), M. Kazmierski; SWEDEN: MALMO: J. Persson, MD (principal investigator), G. Osting;

Endothelial function core laboratory

Vascular Imaging Center Utrecht, Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands. Michiel Bots, MD, PhD; Ronald P. Stolk, MD, PhD; Rudy Meijer, Dicky Mooiweer-Bogaerdt ; Frank Leus, Brigitte Wernert, Eefje Spithoven, (http://www.juliuscenter.nl/research facilities/vascular imaging center)

EUROPA Executive Committee

Bertrand M, Ferrari R, Fox K, Remme W.J, Simoons M.

EUROPA Steering Committee

Aldershville J, Denmark; Hildebrandt P, Bassand JP, France; Cokkinos D, Greece; Toutouzas P, Greece, Eha J, Estonia; Erhardt L,Sweden; Erikssen J, Noway; Grybauskas R, Lithuania; Kalnins U, Latvia; Karsch K, Sechtem U, Germany; Keltai M, Hungary; Klein W, Austria; Luescher T, Switzerland; Mulcahy D, Ireland; Nieminen M, Finland; Oto A, Ozsaruhan O, Turkey; Paulus W, Belgium; Providencia L, Portugal; Remme W J, the Netherlands; Riecansky I,Slovakia; Ruzyllo W, Poland; Santini U, Tavazzi L, Italy; Soler-Soler J, Spain; Widimsky P, Czech Republic.

References

CONSENSUS Trial Study Group. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure: results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). N Engl J Med 1987;316:1429–35.

Kjekshus J, Swedberg K, Snapinn S. Effects of enalapril on long-term mortality in severe congestive heart failure: CONSENSUS trial group. Am J Cardiol 1992;69:103–7.

SOLVD Investigators. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 1991;325:293–302.

Acute Infarction Ramipril Efficacy (AIRE) Study Investigators. Effect of ramipril on mortality and morbidity of survivors of acute myocardial infarction with clinical evidence of heart failure. Lancet 1993;342:821–8.

Hall AS, Murray GD, Ball SG. Follow-up study of patients randomly allocated ramipril or placebo for heart failure after acute MI: AIRE Extension (AIREX) study. Lancet 1997;349:1493–7.

Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E, Moye LA, Basta L, Brown EJ Jr, Cuddy TE, et al. Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the survival and ventricular enlargement trial. The SAVE Investigators. N Engl J Med 1992;327:669–77.

SOLVD Investigators. Effect of enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions. N Engl J Med 1992;327:685–91.

Swedberg K, Held P, Kjekshus J, Rasmussen K, Ryden L, Wedel H. Effects of the early administration of enalapril on mortality in patients with acute MI: results of the Cooperative New Scandinavian Enalapril Survival study II (CONSENSUS-11). N Engl J Med 1992;327:678–84.

Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico. GISSI-3: effects of lisinopril and transdermal glyceryl trinitrate singly and together on six-week mortality and ventricular function after acute MI. Lancet 1994;343:1115–22.

ISIS-4 (Fourth International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. ISIS-4: a randomized factorial trial assessing early oral captopril, oral mononitrate and intravenous magnesitun sulphate in 58,050 patients with suspected acute MI. Lancet 1995;345:669–85.

Survival of MI Long-term Evaluation (SMILE) Study Investigators, Ambrosioni E, Borghi C, Magnani B. The effect of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor zofenopril on mortality and morbidity after anterior MI. N Engl J Med 1995;332:80–5.

Rutherford JD, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, Davis BR, Flaker GC, Kowey PR, et al. Effects of captopril on ischemic events after MI: results of the Survival And Ventricular Enlargement trial (SAVE investigators). Circulation 1994;90:1731–8.

Yusuf S, Pepine CJ, Garces C, Pouleur H, Salem D, Kostis J, et al. Effect of enalapril on MI and unstable angina in patients with low ejection fractions. Lancet 1992;340:1173–78.

Borghi C, Ambrosioni E. Evidence-based medicine and ACE inhibition. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1998;32:S24–35.

Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G. Effects of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients: the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation study investigators. N Engl J Med 2000;342:145–53.

The European Trial on Reduction of Cardiac Events with Perindoril in Stable Coronary Artery Disease Investigators. Efficacy of perindopril in reduction of cardiovasacular events among patients with stable coronary artery disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre trial (EUROPA). Lancet 2003;362:782–88.

Braunwald E, Domanski MJ, Fowler SE, Geller NL, Gersh BJ, Hsia J, et al. Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition in stable coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2058–68.

Khalil ME, Basher AW, Brown EJ Jr, Alhaddad IA. A remarkable medical story: benefits of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in cardiac patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:1757–64.

Bots ML, Remme WJ, Luscher TF, Grobbee DE. Perindopril-Function of the Endothelium in Coronary Artery Disease: The PERFECT study–substudy of EUROPA: rationale and design. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2002;16:227–36.

de Roos NM, Bots ML, Katan MB. Replacement of dietary saturated fatty acids by trans fatty acids lowers serum HDL cholesterol and impairs endothelial function in healthy men and women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001;21:1233–7.

van Venrooij FV, Van De Ree MA, Bots ML, Stolk RP, Huisman MV, Banga JD. Aggressive lipid lowering does not improve endothelial function in type 2 diabetes: the Diabetes Atorvastatin Lipid Intervention (DALI) Study: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1211–6.

Celermajer DS, Adams MR, Clarkson P, Robinson J, McCredie R, Donald A et al. Passive smoking and impaired endothelium dependent arterial dilatation in healthy young adults. N Eng J Med 1996;334:150–4.

Anderson TJ, Uehata A, Gerhard MD, Meredith IT, Knab S, Delagrange D et al. Close relation of endothelial function in the human coronary and peripheral circulations. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;26:1235–41.

Wilmink HW, de Kleijn MJ, Bots ML, Bak AA, van der Schouw YT, Engelen S, et al. Lipoprotein (a) is associated with endothelial function in healthy postmenopausal women. Atherosclerosis 2000;153:249–54.

Hornig B, Kohler C, Drexler H. Role of bradykinin in mediating vascular effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in humans. Circulation 1997;95:1115–8.

Zhuo JL, Mendelsohn FA, Ohishi M. Perindopril alters vascular angiotensin-converting enzyme, AT(1) receptor, and nitric oxide synthase expression in patients with coronary heart disease. Hypertension 2002;39:634–8.

Su JB, Barbe F, Crozatier B, Campbell DJ, Hittinger L. Increased bradykinin levels accompany the hemodynamic response to acute inhibition of angiotensin-converting enxyme in dogs with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1999;34:700–10.

Campbell DJ, Kladis A, Duncan AM. Effects of converting-enzyme inhibitors on angiotensin and bradykinin peptides. Hypertension 1994;23:439–49.

Ghiadoni L, Magagna A, Versari D, Kardasz I, Huang Y, Taddei S, et al. Different effect of antihypertensive drugs on conduit artery endothelial function. Hypertension 2003;41:1281–86.

de Roos NM, Bots ML, Schouten EG, Katan MB. Within-subject variability of flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery in healthy men and women: implications for experimental studies. Ultrasound Med Biol 2003;29:401–6.

Yavuz D, Koc M, Toprak A, Akpinar I, Velioglu A, Deyneli O, et al. Effects of ACE inhibition and AT1-receptor antagonism on endothelial function and insulin sensitivity in essential hypertensive patients. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 2003;4:197–203.

Tezcan H, Yavuz D, Toprak A, Akpinar I, Koc M, Deyneli O et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on endothelial function and insulin sensitivity in hypertensive patients. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 2003;4:119–23.

Ghiadoni L, Magagna A, Versari D, Kardasz I, Huang Y, Taddei S, et al. Different effects of antihypertensive drugs on conduit artery endothelial function. Hypertension 2003;41:1281–86.

Ellis GR, Nightingale AK, Blackman DJ, Anderson RA, Mumford C, Timmins G, et al. Addition of candesartan to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor therapy in patients with chronic heart failure does not reduce levels of oxidative stress. Eur J Heart Fail 2002;4:193–9.

Bae JH, Bassenge E, Lee HJ, Park KR, Park CG, Park KY, et al. Impact of postprandial hypertriglyceridemia on vascular responses in patients with coronary artery disease: effects of ACE inhibitors and fibrates. Atherosclerosis 2001;158:165–71.

Cheetham C, O’Driscoll G, Stanton K, Taylor R, Green D. Losartan, an angiotensin type I receptor antagonist, improves conduit vessel endothelial function in type II diabetes. Clin Sci (Lond) 2001;100:13–7.

Schalkwijk CG, Smulders RA, Lambert J, Donker AJ, Stehouwer CD. ACE-inhibition modulates some endothelial functions in healthy subjects and in normotensive type 1 diabetic patients. Eur J Clin Invest 2000;30:853–60.

Anderson TJ, Elstein E, Haber H, Charbonneau F. Comparative study of ACE-inhibition, angiotensin II antagonism, and calcium channel blockade on flow-mediated vasodilation in patients with coronary disease (BANFF study). J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:60–6.

McFarlane R, McCredie RJ, Bonney MA, Molyneaux L, Zilkens R, Celermajer DS, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition and arterial endothelial function in adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 1999;16:62–6.

Koh KK, Bui MN, Hathaway L, Csako G, Waclawiw MA, Panza JA, et al. Mechanism by which quinapril improves vascular function in coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 1999;83:327–31.

Wilmink HW, Banga JD, Hijmering M, Erkelens WD, Stroes ES, Rabelink TJ. Effect of angiotenisn converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor antagonism on post prandial endothelial function. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;34:140–45.

Mullen MJ, Clarkson P, Donald AE, Thomson H, Thorne SA, Powe AJ, et al. Effect of enalapril on endothelial function in insulin dependent diabetic patients: a randomised double blind study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;31:1330–35.

Mancini GB. Long term use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors to modify endothelial dysfunction: a review of clinical investigations. Clin Invest Med 2000;23:144–61.

Mancini GB, Henry GC, Macaya C, O’Neill BJ, Pucillo AL, Carere RG, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition with quinapril improves endothelial vasomotor dysfunction in patients with coronary artery disease. The TREND (Trial on Reversing ENdothelial Dysfunction) Study. Circulation 1996;94:258–65.

Plotnick GD. Corretti M. Vogel RA. Effect of antioxidant vitamins on the transient impairment of endothelium-dependent brachial artery vasoactivity following a single high-fat meal. JAMA 1997;278:1682–6.

Wilmink HW, Twickler MB, Banga JD, Dallinga-Thie GM, Eeltink H, Erkelens DW, et al. Effect of statin versus fibrate on postprandial endothelial dysfunction: role of remnant-like particles. Cardiovasc Res 2001;50:577–82.

Bots ML, Westerink J, Rabelink TJ, de Koning EJC. Assessment of flow mediated vasodilatation of the brachial artery: effects of technical aspects of the FMD measurement on the FMD response. Eur Heart J 2005;26:363–8.

Dupuis J, Tardif JC, Cernacek P, Theroux P. Cholesterol reduction rapidly improves endothelial function after acute coronary syndromes. The RECIFE (reduction of cholesterol in ischemia and function of the endothelium) trial. Circulation 1999;99:3227–33.

Simons LA, Sullivan D, Simons J, Celermajer DS. Effects of atorvastatin monotherapy and simvastatin plus cholestyramine on arterial endothelial function in patients with severe primary hypercholesterolaemia. Atherosclerosis 1998;137:197–203.

Ceconi C, Fox KM, Remme WJ, Simoons ML, Bertrand M, Parrinello G, et al. ACE inhibition with perindopril and endothelial function. Results of a substudy of the EUROPA study: PERTINENT. Cardiovasc Res 2007;73:237–46.

Acknowledgement

The PERFECT study is supported by a grant (protocol no CL3-O949O-144) from Institut de Recherches Internationales SERVIER (IRIS), Paris, France.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

The EUROPA-PERFECT investigators are listed at the end of the article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bots, M.L., Remme, W.J., Lüscher, T.F. et al. ACE Inhibition and Endothelial Function: Main Findings of PERFECT, a Sub-Study of the EUROPA Trial. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 21, 269–279 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-007-6041-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-007-6041-3