Abstract

A typical acquisition protocol for multi-row detector computed tomography (MDCT) angiography is to obtain all phases of the cardiac cycle, allowing calculation of ejection fraction (EF) simultaneously with plaque burden. New MDCT protocols scanner, designed to reduce radiation, use prospectively acquired ECG gated image acquisition to obtain images at certain specific phases of the cardiac cycle with least coronary artery motion. These protocols do not we allow acquisition of functional data which involves measurement of ejection fraction requiring end-systolic and end-diastolic phases. We aimed to quantitatively identify the cardiac cycle phase that produced the optimal images as well as aimed to evaluate, if obtaining only 35% (end-systole) and 75% (as a surrogate for end-diastole) would be similar to obtaining the full cardiac cycle and calculating end diastolic volumes (EDV) and EF from the 35th and 95th percentile images. 1,085 patients with no history of coronary artery disease were included; 10 images separated by 10% of R–R interval were retrospectively constructed. Images with motion in the mid portion of RCA were graded from 1 to 3; with ‘1’ being no motion, ‘2’ if 0 to <1 mm motion, and ‘3’ if there is >1 mm motion and/or non-interpretable study. In a subgroup of 216 patients with EF > 50%, we measured left ventricular (LV) volumes in the 10 phases, and used those obtained during 25, 35, 75 and 95% phase to calculate the EF for each patient. The average heart rate (HR) for our patient group was 56.5 ± 8.4 (range 33–140). The distribution of image quality at all heart rates was 958 (88.3%) in Grade 1, 113 (10.42%) in Grade 2 and 14 (1.29%) in Grade 3 images. The area under the curve for optimum image quality (Grade 1 or 2) in patients with HR > 60 bpm for phase 75% was 0.77 ± 0.04 [95% CI: 0.61–0.87], while for similar heart rates the area under the curve for phases 75 + 65 + 55 + 45% combined was 0.92 ± 0.02. LV volume at 75% phase was strongly correlated with EDV (LV volume at 95% phase) (r = 0.970, P < 0.001). There was also a strong correlation between LVEF (75_35) and LVEF (95_35) (r = 0.93, P < 0.001). Subsequently, we developed a formula to correct for the decrement in LVEF using 35–75% phase: LVEF (95_35) = 0.783 × LVEF (75_35) + 20.68; adjusted R 2 = 0.874, P < 0.001. Using 64 MDCT scanners, in order to acquire >90% interpretable studies, if HR < 60 bpm 75% phase of RR interval provides optimal images; while for HR > 60 analysis of images in 4 phases (75, 35, 45 and 55%) is needed. Our data demonstrates that LVEF can be predicted with reasonable accuracy by using data acquired in phases 35 and 75% of the R–R interval. Future prospective acquisition that obtains two phases (35 and 75%) will allow for motion free images of the coronary arteries and EF estimates in over 90% of patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Typical acquisition protocols for coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) is to obtain all phases of the cardiac cycle (RR-interval) allowing calculation of ejection fraction (EF) simultaneously with plaque burden [1, 2]. Recently increased concern for radiation exposure has led to a shift towards adopting dose modulation acquisition protocols for CCTA imaging [3, 4]. These protocols target specific phases of the RR-interval that have been shown to produce the best coronary image quality, and predominantly unaffected by motion artifact.

Previous experience from electron beam computed tomography (EBCT) and MDCT, using retrospective overlapping helical acquisition (RS-OHA) technique, showed that image quality is best acquired at certain time phases of the cardiac cycle (referred to as the percentage time of the R–R interval) when the coronary arteries, especially the right coronary artery (RCA), are near still [3, 5, 6]. In all these studies, the 35 or 75% phases have shown to produce the most interpretable images [7–9]. However, the problem lies in volume measurement for end diastolic volume (EDV) and end systolic volume (ESV). Whereas ESV is the LV volume measured at the 35% phase, in more that 90% of the cases, the LV volume at 75% phase is never the actual EDV [3]. The latter is best measured at the 95% phase. Consequently, the adoption of prospective imaging protocols has made determining the true EDV on CT impossible, as images are only obtained at one phase range, which does not include the 95% phase.

In this study, we aim to describe the phase of the R–R interval in the cardiac cycle that produced the optimal images in regards to RCA motion for a large cohort of 1,085 patients undergoing RS-OHA 64-MDCT, gantry rotation speed 0.35 s, with various heart rates. We also studied whether the 75% phase can serve as a surrogate for end-diastole and whether it is accurate enough for EF calculations, with 35% phase as the end systolic phase of the cardiac cycle.

Methods

Patient population

The study includes data acquired from patients referred to our center (Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA) for cardiac computed tomography angiography (CCTA). 1,085 consecutive patients with no history of coronary artery disease (CAD) undergoing 64 detector row MDCT angiography from September, 2006 to September, 2008 were included. The various indications for the study included: chest pain, shortness of breath, abnormal or equivocal stress test, cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, or syncope. Patients were excluded if found to have an irregular heart rate, allergy to contrast medium or impaired renal function. This study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board of our hospital.

Patient preparation

The patients were prepared in usual manner as described in earlier studies. In brief, patients received explanation about the procedure and informed consent was obtained. Upon arrival to our center, if the patient’s base line HR was more than 80 bpm, 100 mg of atenolol was given orally and was asked to wait for 1 h. Alternatively, if the HR < 80 bpm the patient was attached to the scanner without any delay. On the scanner, if the HR was >60 bpm, intravenous (IV) metoprolol was administered in doses of 5 mg every 1 min until the HR was brought below 60 bpm or a total IV dose of 40 mg was given or the systolic blood pressure (SBP) dropped to <90 mm Hg. Intravenous diltiazem was also used to complement the beta blocker if needed. Three phase injection using a Dual Barrel Injector with contrast/saline mix was administered intravenously as follows: 5 ml/s for 12 s (60 ml contrast), then 5 ml/s for 10 s (50–20 ml contrast plus 30 ml saline) and finally 5 ml/s for 4 s (20 ml of saline), injection protocols were varied based upon patient characteristics (length of heart, heart rate, body habitus).

Image acquisition and analysis

Computed tomography angiography study was completed with 64-MDCT (Light Speed VCT, General Electric Medical System, Milwaukee, WI). The technique of the cardiac retrospective overlapping helical acquisition was completed utilizing a 0.35-s scan gantry rotation speed and a 64 × 0.625 mm slices. The pitch was automatically determined by the heart rate. The reconstruction field of view (SFOV) was small (12–17 cm, mean 15 cm) with a voxel size in 0.29 × 0.29 × 0.6 mm³. An energy setting of 120 kVp was used for patients weighing ≥85 kg. For patients who were <85 kg, an energy setting of 100 kVp was selected. The tube current or mA was 200–800; also determined based on the body habitus. The image reconstructions were done using 10 phases in 10% of each RR interval. The total scan time was about 5–6 s. Images were reviewed in consensus by two interpretors (MJB and SM) with each having more than 10 years experience in reading cardiac CTAs.

Of the 10 phases, the phase that provided the best image of the segment with minimal motion of mid portion of RCA was referred to as the optimal phase. The mid portion of the RCA was chosen as reference point in axial images, because this segment is most likely to be affected by the cardiac motion causing image artifact. Motion distance was defined as the distance from the center of the artery lumen to the tail of the motion. The grading system is shown in (Table 1; Fig. 1).

We randomly selected a cohort of 216 patients who met the following criteria: (1) All patients had excellent image quality obtained using the retrospective helical acquisition protocol with 10 sets of images present; (2) patients with EF < 50% were excluded. In this group of patients an independent interpretor (SM) measured ejection fraction using 35 and 95% of cardiac cycle as well as using 35 and 95% of the cardiac cycle as end systolic and end diastolic phases, respectively using the ‘Auto Ejection Fraction’ protocol on the workstation (Advantage 4.4, General Electric, Milwaulkee WI).

Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed using SPSS 15 statistical software. Categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-Square test and Continuous variables using student t-test. Area under the curve (AUC) was constructed to access image quality for HR > 60 bpm at various phases of RR interval.

The means of two independent variables, each with its own set of continuous data points, were compared using Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test as statistically necessary. Similarly, the Spearman’s or Pearson’s correlation tests were used to determine the association between continuous variables. For ejection fraction correlation, a linear regression model was used to determine statistically significant predictors of the continuous dependent variable (EDV or LVEF). A regression model residuals analysis including a regression studentized residual plot versus regression standardized predicted value plots and a regression standardized residual histogram distribution curve were used to test the regression model assumptions hold. For all analyses, a criterion for statistical significance was set at a 2-tailed P value < 0.05.

Results

Optimal image quality with respect to RCA motion

In this cohort of 1,085 patients, 757 patients were males (69.76%) and the average HR of this group was 56.72 ± 9.43 beats per minute (range 33–140). (Table 2). The distribution of image quality was 958 (88.3%) Grade 1, 113 (10.42%) Grade 2 and 14 (1.29%) Grade 3 images. The distribution of optimal images (Grades 1 and 2) was stratified based on HR and phase at which it was acquired (Table 3).

Utilizing 75% phase of the R–R interval to capture images for HR < 60 gave an interpretable image quality in 93.2% of the patients (P ≤ 0.001), while using 4-phase [35% + 45% + 55% + 75%] for HR > 60 bpm gave an interpretable image in 92.4% of the patients (P = 0.0001) [Interpretable image: Grades 1 and 2]. Figure 2 and Table 4, shows the two models (75% phase and 4 phases [35% + 45% + 55% + 75%]) created to assess the ability of the R–R interval to predict interpretable images in 64 slice MDCT. The area under the curve (AUC) for optimal images for HR > 60 bpm was 0.77 ± 0.04 [95% CI: 0.61–0.87, P = 0.008] in 75% phase. For HR > 60 bmp, the AUC for optimal images in phases 35% + 45% + 55% + 75% of RR interval combined was 0.92 ± 0.02 [95% CI: 0.83–0.96, P ≤ 0.001].

Comparison of ejection fraction utilizing 75% phase as end-diastole vs. 95% phase of the RR interval

In this group, 63.4% (137/216) were males, 2.3% (5/216) were smokers, 20.8% (45/216) were diabetic, 32.4% (70/216) had dyslipidemia, 44.4% (96/216) were hypertensive and 52.3% (113/216) had a family history of CAD.

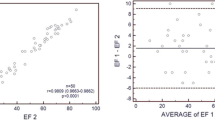

Of the parameters tested for an association with EDV, we found LV volume at 75% phase, age, weight, height, heart rate, and LV mass to be correlated with EDV. Two-tailed t-tests were performed on the difference between the mean EDV of several subgroups of patients (Table 5). A similar analysis was performed to identify predictors of LVEF (Table 6).We then incorporated all the variables that were found to be associated with EDV and LVEF into two multivariable linear regression analyses: one studied the correlation of these variables with EDV and the other with LVEF. The following formulas were the outcomes of the analyses:

-

1.

EDV = [1.048 × (LV volume 75%)] + [0.014 × (LV mass)] + (0.223 × heart rate) − 14.83 (Adj. R 2 0.94, P < 0.001)

-

2.

LVEF = [0.78 × LVEF (75_35)] + (0.12 × heart rate) + (0.066 × age) + 10.47 (Adj. R 2 0.89, P < 0.001)

To further analyze our regression models, we studied the residuals and their variance. We transformed the regression residuals to standardized residuals and then constructed a histogram plot that showed normal distribution of standardized residuals. Figure 3 is a scatterplot of the studentized residuals for the dependent variable LVEF using 95 and 35% phases versus the standardized predicted value for that regression model. Figure 4 is a similar scatterplot for dependent variable LV volume at 95% phase. Both scatter plots show that the residuals have a random distribution around zero and that the degree of scatter appears constant across the predicted values. Considering use in daily clinical practice, we also derived abridged versions of the above 2 formulas and plotted their corresponding graphs (Figs. 5, 6).

Abridged formulas:

-

1.

EDV = 1.064 × (LV volume at 75%) + 14.43 (Adj. R 2 linear = 0.94, P < 0.001)

-

2.

LVEF = 0.782 × LVEF (75_35) + 20.76 (Adj. R 2 0.87, P < 0.001).

Discussion

Minimizing radiation exposure through ECG triggered X-ray tube activation is a step towards making coronary CTA safer. Using the RS-OHA technique, where the X-ray beam is continuously on, all phases of the cardiac cycle are available. Using the SSPA technique where the X-ray beam is on only at targeted points of the RR interval significantly decreases the radiation exposure, but does not allow for end-diastole (95th percentile) to be obtained [1, 10, 11]. Selecting the targeted intervals that produce the best image quality is HR dependent. In our study we reviewed coronary CTAs performed by 64-MDCT on 1,085 patients to determine optimum phases of R–R interval in regards to image quality at varying heart rates. We found that, whereas targeting the 75% phase of the cardiac cycle (R–R interval) produced >90% of the best image quality at HR < 60 bpm, heart rates of >60 and <70 bpm reduced the frequency of optimal image quality to 84%, and HR > 70 bpm decreased it further to 43%. Furthermore, at HR > 60 bpm, a significant proportion of best image quality is produced at the 35, 45 and 55% phases of the R–R interval. Hence, based on our results, for patients with HR > 60 bpm reconstructing images at the 35, 45, 55 and 75% phases produced interpretable images in 92% of the cases.

Coronary artery motion, among others, remains to be a significant cause of artifact in images produced by 64-MDCT [12]. Peak velocities of motion were found to be caused by ventricular systole, diastole and atrial contraction. Among the 3 epicardial vessels, the RCA displayed the highest mean motion velocity (50–69.5 mm/s) followed by the left circumflex, then the left anterior descending [13, 14]. Not surprisingly, since coronary motion is primarily determined by ventricular and atrial motion, coronary motion increases with increasing HR. Moreover, with increasing HR all the phases of the cardiac cycle are affected to varying degrees; thus shifting the coronary motion velocity peaks and troughs [14]. To further support this observation, in a previous EBCT study, Mao et al. [3] showed that among the various segments of the R–R interval, TR (ventricular diastole) and TP (ventricular diastole (TR) excluding PR duration) were subjected to the most variation in comparison to PR (from beginning of P wave to R peak) and RT segments (from R peak to the end of T wave) in electrocardiogram (ECG) with increasing HR. Hence, whereas at HR < 60 bpm RCA motion velocity is minimal at 75% phase, at HR > 60 bpm minimal RCA motion velocity is seen at earlier phases closer to “ventricular systole” (35 and 45% R–R interval phases). In line with the latter observation, our results showed better RCA image quality in the 45 and 55% interval phases for patients with HR > 70 bpm. Brodoefel et al. [15] in their study involving 100 patients without heart rate control concluded that along with calcification, heart rate variability significantly impairs image quality of coronary vessels while using Dual-source CT. A similar study [4] on 60 patients but with HR < 75 bpm showed no significant difference in image quality score for the total coronary segments comparing SSAP CT angiography to RS-OHA CT angiography. Earls et al. [16], in a cohort of 203 patients (82 underwent RS-OHA CT and 121 underwent SSPA) and HR < 70 bpm, found comparable image quality with the 2 techniques but with reduced radiation exposure in SSPA. Frydrychowicz et al. [17], suggested that the ‘60% phase’ portrayed the best image quality in HR controlled patients while Leschka et al. [18], on 125 patients obtained best image quality in the 50–80% range of the R–R interval in >50% of the coronary segments. The best reconstruction time shifted to end systole (25–40% of the R–R interval) with higher HR. Pannu et al. [19] in a group of 50 patients with a mean HR of 59.8 bpm. Have shown that 70% phase produces the best images and that the mid-RCA is the most affected segment by cardiac motion. Based on this, we suggest that for patients undergoing 64-MDCT and with a HR > 60 bpm, either retrospective triggering or snap shot pulse acquisition (SSPA) with a wide range of acquisition be applied (35–75%).

In the present study in a smaller cohort of 216 patients with EF > 50% and no evidence of MI, we showed that that LV volume measured at the 75% phase can serve as surrogate for EDV (LV volume at 95% phase), and therefore be used to calculate LVEF with reasonable accuracy. EDV is associated with several parameters, however, only LV volume at 75%, LV mass and heart rate remained as statistically significant independent predictors of EDV in a multivariable linear regression analysis. We therefore derived two equations for estimating EDV and LVEF: a comprehensive equation including LV volume at the 75% phase, heart rate and LV mass; and an abridged form that includes only LV volume at the 75% phase which we believe will be easier to use in a clinical setting. A significant radiation dose reduction can be obtained by performing prospectively triggered scans in comparison to retrospective ECG-gated CT scan with dose modulation for functional evaluation. For example, in a study using dual source CT scan, an average radiation dose was 9.0 mSv for the retrospective CT protocol with dose modulation vs. 2.9 mSv for the prospective CT protocol (both use 120 kV and result in similar image quality). Therefore, using two prospective scans against one retrospective scan would give approximately 36% dose reduction (5.8 vs. 9.0 mSv) [20].

End diastolic volume is achieved at the end of diastolic filling, which starts at mitral valve opening and ends at mitral valve closure. Since the diastolic period is characterized by early filling (E), diastasis and late filling (A—atrial kick dependent) phases, then the volume of blood in the LV at 75% is essentially dependent on where the 75% time point is relative to the subsequent diastolic phases. The well known predictors of E and A are: age, gender, LV hypertrophy [21], ischemic disease [22], DM type 2 (independent of LVH), valvular heart disease, heart rate (which includes intrinsically the QT, TP and PR intervals) [23] and preload [24]. These variables were mostly reported to be predictors of LV volume at the 95% phase (EDV), but not all of them were found to be statistically significant independent predictors in our final regression equation. Several reasons can account for this. One reason is that the more subtle or weaker associations may not have become apparent due to the small sample size (N = 216). We note that whereas Doppler echocardiography remains the reference standard to derive E and A velocities [25], echo derivation of LV mass is limited with the need for mathematical model assumptions [as evidenced by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)] [26]. Contrastingly, previous studies have shown that cardiac CT can accurately quantify LV mass and volumes compared with cardiac [27–29] MRI.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. We looked at RCA to access motion and predicted the interpretability of the study. The circumflex coronary artery is the second most common artery affected by motion, and this was not assessed in this study. We acquired images at 10% intervals, some studies have constructed the images at 5% of intervals but experience at our center has not seen any added benefit of further segmentation of image sets.

We did not separately include the QT, TP and PR intervals in our regression model for ejection fraction calculation. Failing to include these intervals is a limitation that is a consequence of the study’s retrospective design. Several groups, including ours, have demonstrated that with heart rate variation these intervals are affected to varying degrees [3], and therefore the 75% time point of the RR-interval might vary as well. Additionally, given that ECG documentation was not available to include in our analysis, we cannot make note of the presence of a conduction problem that could have impacted our results (e.g. first degree atrio-ventricular block).

It should also be mentioned that the CCTA protocol includes giving beta blockers and nitrates (100% of our cohort received both), which can further affect both heart rate and preload. However, this is the standard protocol used at most centers. Additionally, our results cannot be extrapolated to patients with heart failure (LV EF < 50%) or evidence of MI (aneurysms in particular).

Not all the patients can be scanned using prospective—ECG triggered CT image acquisition e.g. in patients with atrial fibrillation. The maximum dose saving is achieved using the shortest acquisition window, which does not allow any flexibility in post-acquisition phase adjustment. This can potentially result in sub-optimal image quality and compromise the diagnostic value of the exam. The LVEF (75_35) values calculated from a retrospective ECG-gated scan and two prospective scans triggered at 35 and 75% of the R–R interval are not going to be necessarily the same, especially for patients with some heart rate variability. An ideal study design should compare the “true LVEF(75_35)” calculated from the two prospective scans with a “gold standard LVEF” calculated from the best end-systolic and best end-diastolic phases obtained using either retrospective CT or MRI. This study would be hard to conduct using retrospective CT due to exponential radiation exposure in human beings.

Conclusions

We demonstrate in a cohort of 1,085 patients that the optimal RCA image quality using a 64 MDCT scanner is heart rate dependent. For HR < 60 bpm the 75% phase of the R–R interval should provide adequate image quality in more than 90% of the cases. However, short of better HR control, when the HR is >60 bpm acquiring 4 phases (75, 35, 45 and 55%) will produce an interpretable study in >90% of CT angiographies. While using dose-modulation protocols in CCTA to reduce radiation exposure in order to estimate EDV and LV EF, we should aim to acquire both the 35 and 75% phases.

Thus, prospective acquisition protocols that obtain two phases (35 and 75%) will allow for motion free images of the coronary arteries and will potentially estimate EF in all patients suitable for prospective triggering. Future prospectively designed large-scale studies aimed at eliminating some, if not all, of the above cited limitations can be extremely useful and promising.

References

Kopp AF, Kuttner A, Trabold T, Heuschmid M, Schroder S, Claussen CD (2004) Multislice CT in cardiac and coronary angiography. Br J Radiol 77:87–97

Schoenhagen P, Halliburton SS, Stillman AE et al (2004) Noninvasive imaging of coronary arteries: current and future role of multi-detector row CT. Radiology 232:7–17

Mao S, Lu B, Takasu J, Oudiz RJ, Budoff MJ (2003) Measurement of the RT interval on ECG records during electron-beam CT. Acad Radiol 10(6):638–643

Hirai N, Horiguchi J, Fujioka C, Kiguchi M, Yamamoto H, Matsuura N, Kitagawa T, Teragawa H, Kohno N, Ito K (2008) Prospective versus retrospective ECG-gated 64-detector coronary CT angiography: assessment of image quality, stenosis, and radiation dose. Radiology 248(2):424–430 Epub 2008 Jun 23

Wintersperger BJ, Nikolaou K, von Ziegler F, Johnson T, Rist C, Leber A, Flohr T, Knez A, Reiser MF, Becker CR (2006) Image quality, motion artifacts, and reconstruction timing of 64-slice coronary computed tomography angiography with 0.33-second rotation speed. Invest Radiol 41(5):436–442

Lu B, Mao SS, Zhuang N, Bakhsheshi H, Yamamoto H, Takasu J, Liu SC, Budoff MJ (2001) Coronary artery motion during the cardiac cycle and optimal ECG triggering for coronary artery imaging. Invest Radiol 36(5):250–256

Matsuura N, Horiguchi J, Yamamoto H, Hirai N, Tonda T, Kohno N, Ito K (2008) Optimal cardiac phase for coronary artery calcium scoring on single-source 64-MDCT scanner: least interscan variability and least motion artifacts. AJR Am J Roentgenol 190(6):1561–1568 PMID: 18492907

Francone M, Napoli A, Carbone I, Cavacece M, Nardis PG, Lanciotti K, Visconti S, Bertoletti L, Di Castro E, Catalano C, Passariello R (2007) Noninvasive imaging of the coronary arteries using a 64-row multidetector CT scanner: initial clinical experience and radiation dose concerns. Radiol Med 112(1):31–46 Epub 2007 Feb 22

Weustink AC, Mollet NR, Pugliese F, Meijboom WB, Nieman K, Heijenbrok-Kal MH, Flohr TG, Neefjes LA, Cademartiri F, de Feyter PJ, Krestin GP (2008) Optimal electrocardiographic pulsing windows and heart rate: effect on image quality and radiation exposure at dual-source coronary CT angiography. Radiology 248:792–798

Lalande S, Johnson BD (2008) Diastolic dysfunction: a link between hypertension and heart failure. Drugs Today (Barc) 44(7):503–513 Review. PMID: 18806901 [PubMed-indexed for MEDLINE]

Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, St John Sutton M, Stewart W (2005) Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s guidelines and standards committee and the chamber quantification writing group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 18(12):1440–1463

Schroeder S, Achenbach S, Bengel F, Burgstahler C, Cademartiri F, de Feyter P, George R, Kaufmann P, Kopp AF, Knuuti J, Ropers D, Schuijf J, Tops LF, Bax JJ, Working Group Nuclear Cardiology and Cardiac CT, European Society of Cardiology, European Council of Nuclear Cardiology (2008) Cardiac computed tomography: indications, applications, limitations, and training requirements: report of a Writing Group deployed by the Working Group Nuclear Cardiology and Cardiac CT of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Council of Nuclear Cardiology. Eur Heart J 29(4):531–556 Epub 2007 Dec 15

Mao S, Lu B, Oudiz RJ, Bakhsheshi H, Liu SC, Budoff MJ (2000) Coronary artery motion in electron beam tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr 24(2):253–258

Husmann L, Leschka S, Desbiolles L, Schepis T, Gaemperli O, Seifert B, Cattin P, Frauenfelder T, Flohr TG, Marincek B, Kaufmann PA, Alkadhi H (2007) Coronary artery motion and cardiac phases: dependency on heart rate implications for CT image reconstruction. Radiology 245(2):567–576 Epub 2007 Sep 11

Brodoefel H, Burgstahler C, Tsiflikas I, Reimann A, Schroeder S, Claussen CD, Heuschmid M, Kopp AF (2008) Dual-source CT: effect of heart rate, heart rate variability, and calcification on image quality and diagnostic accuracy. Radiology 247(2):346–355 Epub 2008 Mar 27

Earls JP, Berman EL, Urban BA, Curry CA, Lane JL, Jennings RS, McCulloch CC, Hsieh J, Londt JH (2008) Prospectively gated transverse coronary CT angiography versus retrospectively gated helical technique: improved image quality and reduced radiation dose. Radiology 246(3):742–753 Epub 2008 Jan 14

Frydrychowicz A, Pache G, Saueressig U, Föll D, Kotter E, Langer M, Bley TA (2007) Comparison of reconstruction intervals in routine ECG-pulsed 64-row-MSCT coronary angiography in frequency controlled patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 30(1):79–84

Leschka S, Wildermuth S, Boehm T, Desbiolles L, Husmann L, Plass A, Koepfli P, Schepis T, Marincek B, Kaufmann PA, Alkadhi H (2006) Noninvasive coronary angiography with 64-section CT: effect of average heart rate and heart rate variability on image quality. Radiology 241(2):378–385 Epub 2006 Sep 11

Pannu HK, Jacobs JE, Lai S, Fishman EK (2006) Coronary CT angiography with 64-MDCT: assessment of vessel visibility. AJR Am J Roentgenol 187(1):119–126

Alkadhi H, Stolzmann P, Scheffel H, Desbiolles L, Baumüller S, Plass A, Genoni M, Marincek B, Leschka S (2008) Radiation dose of cardiac dual-source CT: the effect of tailoring the protocol to patient-specific parameters. Eur J Radiol 68:385–391

Lalande S, Johnson BD (2008) Diastolic dysfunction: a link between hypertension and heart failure. Drugs Today (Barc) 44(7):503–513 Review. PMID: 18806901 [PubMed-indexed for MEDLINE]

Nakae I, Matsuo S, Matsumoto T, Mitsunami K, Horie M (2008) Clinical significance of diastolic function as an indicator of myocardial ischemia assessed by 16-frame gated myocardial perfusion SPECT. Ann Nucl Med 22(8):677–683 Epub 2008 Nov 4. PMID: 18982470 [PubMed-in process]

Bombardini T, Gemignani V, Bianchini E, Venneri L, Petersen C, Pasanisi E, Pratali L, Alonso-Rodriguez D, Pianelli M, Faita F, Giannoni M, Arpesella G, Picano E (2008) Diastolic time–frequency relation in the stress echo lab: filling timing and flow at different heart rates. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 21:6–15

Drighil A, Madias JE, Mathewson JW, El Mosalami H, El Badaoui N, Ramdani B, Bennis A (2008) Haemodialysis: effects of acute decrease in preload on tissue Doppler imaging indices of systolic and diastolic function of the left and right ventricles. Eur J Echocardiogr 9(4):530–535 Epub 2008 Mar 27

Movsowitz HD, Movsowitz C, Jacobs LE, Kotler MN (1993) Pitfalls in the echo-Doppler diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Echocardiography 10(2):167–179

O’Dell WG, McCulloch AD (2000) Imaging three-dimensional cardiac function. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2:431–456. doi:10.1146/annurev.bioeng.2.1.431

Nasir K, Katz R, Mao S, Takasu J, Bomma C, Lima JA, Bluemke DA, Kronmal R, Carr JJ, Budoff MJ (2008) Comparison of left ventricular size by computed tomography with magnetic resonance imaging measures of left ventricle mass and volumes: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2(3):141–148 Epub 2008 Jan 31

Raman SV, Shah M, McCarthy B, Garcia A, Ferketich AK (2006) Multi-detector row cardiac computed tomography accurately quantifies right and left ventricular size and function compared with cardiac magnetic resonance. Am Heart J 151(3):736–744

Lessick Jonathan, Mutlak Diab, Rispler Shmuel, Ghersin Eduard, Dragu Robert, Litmanovich Diana, Engel Ahuva, Reisner ShimonA, Agmon Yoram (2005) Comparison of multidetector computed tomography versus echocardiography for assessing regional left ventricular function. Am J Cardiol 96(7):1011–1015

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Isma’eel, H., Hamirani, Y.S., Mehrinfar, R. et al. Optimal phase for coronary interpretations and correlation of ejection fraction using late-diastole and end-diastole imaging in cardiac computed tomography angiography: implications for prospective triggering. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 25, 739–749 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-009-9481-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-009-9481-y