Abstract

Purpose

There are racial and ethnic differences in endometrial cancer incidence and mortality rates; compared with Non-Hispanic White women, Black women have a similar incidence rate for endometrial cancer, but their mortality is higher. Pacific Islander women may also have worse outcomes compared to their White counterparts. We assessed tumor characteristics and adjuvant therapy by racial and ethnic group among endometrial cancer patients treated within the Military Health System, an equal access healthcare organization.

Methods

We retrospectively identified women diagnosed with invasive endometrial cancer among US Department of Defense beneficiaries reported in the Automated Central Tumor Registry database (year of diagnosis: 2001–2018). We compared tumor characteristics and receipt of adjuvant therapy across racial and ethnic groups using Chi-square or Fisher tests. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for risk of all cause mortality were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression models adjusting for age at diagnosis, adjuvant therapy, histology and stage.

Results

The study included 2574 endometrial cancer patients [1729 Non-Hispanic White, 318 Asian, 286 Black, 140 Pacific Islander and 101 Hispanic women]. Among all cases, a higher proportion of Black patients had non-endometrioid histology (46.5% versus ≤ 29.3% in other groups, P < 0.01) and grade 3–4 tumors (40.1% versus ≤ 29.3% in other groups, P < 0.01). In multivariable Cox models, compared with Non-Hispanic White cases, Black endometrial cancer patients had a higher mortality risk (HR 1.43, 95% CI, 1.13–1.83). There was no difference in mortality risk for other racial and ethnic groups.

Conclusion

Black patients with endometrial cancer presented with more aggressive tumor features and they had worse overall survival compared with patients in other racial and ethnic groups. Further study is needed to better direct preventive and therapeutic efforts in order to correct endometrial cancer disparities in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the western world and the fourth most common cancer overall in women in the United States [1]. Fortunately, 67% of patients present with localized disease which is associated with a 5-year relative survival rate of 95% [2]. However, unlike most cancers, the incidence and mortality of endometrial cancer has been rising [1]. Women with early menarche, late menopause, anovulation, unopposed estrogen use and obesity are at increased risk to develop endometrial cancer [3]. The obesity epidemic has been suggested as a possible driver of the rising incidence of endometrial cancer in the United States [4]. Obesity has a more pronounced association with the more common and less aggressive endometrioid endometrial cancer (EEC) which represents about 85% of cases [5]. Conversely, non-endometrioid endometrial cancer (non-EEC), is classically a more aggressive disease. Non-EEC, which disproportionately affects Non-Hispanic Black (hereafter referred to as Black) women [6], is increasing in incidence and has been suggested as the primary reason for the 1.9% annual increase in endometrial cancer mortality [1, 6]. Although Black women have similar age-adjusted incidence rates of endometrial cancer as their Non-Hispanic White (hereafter referred to as White) counterparts [6, 7], they have an 80% increased risk for mortality regardless of stage or histology [8]. There is ongoing research into the causes of this disparity including inquiries into age at time of presentation, sociodemographic characteristics, variability in somatic mutational pattern and standard of care delivery [9,10,11,12].

Two retrospective analyses of data from Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) and the National Cancer Database (NCD) reviewed adherence to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines and established standards of care, respectively, and found that Black patients and those of low socioeconomic status (regardless of race or ethnicity) were less likely to receive standard of care treatment when compared with White patients or those of higher socioeconomic status [8, 10]. Adjustment for perfect adherence to established standards of quality care in patients with stage III disease did not remove a statistically significant higher risk for all-cause mortality in Black versus White endometrial cancer patients [5-year overall survival (OS): HR 1.35, 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.22–1.50]. It is unknown what drives this disparity in outcomes but differences in access to care have been suggested as a possible cause [4].

The United States Department of Defense (DoD) military health system provides equal access to care for all beneficiaries regardless of race and ethnicity or socioeconomic background. The Automated Central Tumor Registry (ACTUR) was established in 1986 as the cancer registry system for the DoD. Previous studies using ACTUR data have shown a higher proportion of non-endometrioid histology in Black versus White endometrial cancer patients (48 versus 24%) and increased all-cause mortality in Black versus White patients (HR: 1.64, 95% CI = 1.19 to 2.27, adjusted for age at diagnosis, diagnosis period, tumor stage, histology, and receipt of adjuvant treatment) [13, 14]. The current study represents the largest ACTUR endometrial cancer study to date with the most contemporary study population and extends analysis to include additional racial and ethnic groups (i.e., Asian, Pacific Islander and Hispanic patients).

Methods

Study population

This study was conducted in patients of the DoD military health system who receive their medical care free of charge. Of the 9.6 million beneficiaries of the military health system, nearly half of them (active duty/reserve and family members) are provided allowances for housing and subsistence that are related to rank and time in service. There are equal opportunities for career advancement and educational opportunities for those who serve in the military. The authors of this paper understand that there are complex structural barriers to healthcare access that persist regardless of equal pay, housing and provider availability; however, the benefit of improved access to care on cancer-related outcomes has been demonstrated in several tumor types in patients treated within the military health system [15,16,17].

Data from the DoD ACTUR database were used to conduct this study. Briefly, the ACTUR database includes data on DoD beneficiaries (including active-duty military personnel, retirees and their dependents) who are diagnosed with cancer or receive cancer treatment at military facilities [13]. Local tumor registrars abstract and enter data for newly diagnosed cancer patients in consultation with gynecologic oncologists. Endometrial cancer was defined as International Classification of Diseases for Oncology 2nd or 3rd revision codes C54.0-54.9 and C55.9 (further details and exclusions are shown in Supplementary Table 1). This study included invasive endometrial cancer cases diagnosed between 2001 and 2018. Data were abstracted from the ACTUR in February 2021 on tumor histology, stage [local, regional, distant or unknown by combining Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) summary stage variables], grade [well (G1), moderate (G2), poor (G3), undifferentiated (G4) or unknown], information on the first course of treatment [surgery (yes/no); receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation] and vital status (all-cause mortality). Racial and ethnic groups were recorded in the registry database using: (1) information that is documented in the beneficiary medical record [which includes health data from the DoD, Department of Veterans Affairs and private sector partners) and outside/community records or documents]; (2) observations made by the treating/managing physicians; or (3) information obtained directly from the patient’s response to the Oncology/Registry Patient Questionnaire (when applicable).

We identified N = 2966 endometrial cancer cases and the following exclusions were applied: not invasive (N = 20); non-epithelial (N = 153); and cases that were not included in the five major racial and ethnic groups that were the focus of this study (N = 219) leaving 2574 cases for the study. In addition, we conducted survival analyses focusing on all cause mortality as the outcome. Death due to endometrial cancer could not be examined because data on the cause of death were not available for most patients. Additional exclusions were applied for the survival analysis: unknown vital status (N = 5); date of diagnosis was the same as the date of death (N = 2); no surgery (N = 157) or missing surgery (N = 31); missing stage (N = 61) leaving 2318 cases for survival analysis. This study was approved by institutional review boards at all participating institutions.

Statistical analysis

We evaluated whether there were differences in tumor characteristics and receipt of the first course of adjuvant therapy by racial and ethnic group using the Chi-square test or Fisher test for small sample sizes. We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the risk of all cause mortality across racial and ethnic groups. Person-time was calculated as the number of days between a patient’s date of diagnosis until the date of last contact or censoring, whichever occurred first. Multivariable models were adjusted for covariates selected a priori because of their known influence on risk of mortality: age at diagnosis (continuous); and receipt of the first course of adjuvant therapy [no adjuvant therapy (reference), radiation therapy, chemotherapy, radiation and chemotherapy, missing]. Multivariable models were stratified by: histology [EEC, non-EEC]; and stage [localized, regional, distant]. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using the method described by Grambsch and Therneau [18]. Histology and stage violated proportional hazards therefore these variables were included as strata terms in the model. No violation of proportional hazards was observed for age and adjuvant therapy.

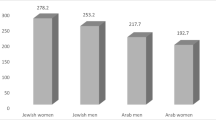

Receipt of adjuvant therapy (receipt of radiotherapy only, chemotherapy only or both) was taken as an indicator for the presence of adverse tumor characteristics that were not available in the current dataset, including invasion of for example the lymphovascular space, tumor size and myometrial invasion [19]; this has particular relevance for patient subgroups (e.g., low grade EEC) who would not typically receive adjuvant therapy. We classified cases according to their age at diagnosis (< 50 years and 50 + years) to approximate premenopausal and postmenopausal disease, respectively, similar to an earlier report [13]. There may be clinical, pathological and etiologic differences for women who develop premenopausal endometrial cancer; this concept has been explored in breast cancer [20] but not as we are aware for endometrial cancer. Descriptive analyses were age-standardized [21]. All statistical tests were two-sided and P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.1.0 [22].

In accordance with the journal’s guidelines, we will provide our data for independent analysis by a selected team for the purposes of additional data analysis or for the reproducibility of this study in other centers if such is requested.

Results

When comparing age-standardized characteristics among endometrial cancer patients by racial and ethnic group, the percentage of fatal cases (death from all causes) was highest among Black women (33.1% followed by 29.4% in Hispanic patients, and ≤ 27.9% in other racial and ethnic groups) (Table 1). Endometrioid histology was most common in all racial and ethnic groups (range, 56.0% of Black patients to 74.7% of White patients) and Black patients had a higher proportion of serous histology (13.9% serous versus ≤ 5.5% in other racial and ethnic groups). The mean age at diagnosis and receipt of surgery was similar across racial and ethnic groups.

When comparing tumor characteristics and receipt of adjuvant therapy (an indicator of adverse tumor characteristics) across racial and ethnic groups, we observed significant differences for histology, stage and grade among all cases (P ≤ 0.04) and among cases who were age 50 + years at diagnosis (P ≤ 0.01) (Table 2). A higher percentage of Black patients had more aggressive tumor characteristics compared with most other racial and ethnic groups. For example, among cases who were age 50 + years at diagnosis, Black patients had a higher proportion of non-EEC histology (48.0% of Black patients versus ≤ 30.1% among other groups, P < 0.01) and grade 3–4 disease (41.2% of Black patients compared with ≤ 32.7% among other groups, P < 0.01). A higher percentage of Black and Asian patients were diagnosed with regional/distant stage disease (age 50 + years, 32.3% of Black, 32.7% of Asian patients compared with ≤ 28.8% for other racial and ethnic groups, P = 0.01). In contrast, in younger patients (age < 50 years) only grade differed by racial and ethnic group (grade 3–4 disease was observed in 33.3% of Black patients compared with ≤ 21.7% patients in other groups, P < 0.01).

Among low grade EEC cases, a lower proportion of Black patients had regional/distant stage disease (all ages, 5.8% versus ≥ 15.2%, compared to others P = 0.01) (Table 3). A smaller percentage of Black and Hispanic patients received adjuvant treatment (all ages, ≤ 13.1% versus 22.5–32.1% in other groups, P = 0.02). Similar patterns were observed among older (age 50 + years) cases. Differences by stage and receipt of adjuvant therapy across racial and ethnic groups were not observed among younger EEC cases.

In patients with localized disease, a higher percentage of Black patients had non-EEC histology (all ages, 35.4% versus ≤ 21.7% in other groups, P < 0.01) (Table 4). Black, Pacific Islander and Hispanic patients presented more often with high grade tumors (all ages, ≥ 19.6% compared to ≤ 11.8% in White and Asian patients, P < 0.01). A higher proportion of Black and Pacific Islander patients received adjuvant therapy (all ages, ≥ 25.7% versus ≤ 21.5% in others, P = 0.02). In patients > 50 years of age, these patterns remained with the exception that the receipt of adjuvant therapy was higher only in Pacific Islander patients (34.2%) versus other groups (≤ 24.2%, P = 0.02). In patients < 50 years of age, only differences by grade were observed across racial and ethnic groups (29.2% of Black patients had grade 3–4 disease versus ≤ 13.3% in others, P = 0.02).

In patients with regional/distant disease, a higher proportion of Black patients had non-EEC and high-grade tumors than other groups (70% versus ≤ 50%; 79.2% versus ≤ 55%, respectively, P < 0.01 for both) (Table 5). These differences retained statistical significance in patients ages 50 + years (P < 0.01 for both) but not in younger patients. Pacific Islander patients received adjuvant therapy more often than other groups (96.7% versus ≤ 82.8%, P < 0.01). This pattern remained in patients 50 years and older but not in younger patients.

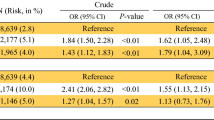

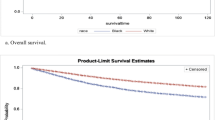

In the present study there was a mean follow-up of 6.7 years (SD = 4.6) between the date of endometrial cancer diagnosis and the date of death or censoring. Risk of all cause mortality was compared across racial and ethnic groups after accounting for age at diagnosis, receipt of adjuvant therapy, histology and stage. We observed that Black patients had a higher mortality risk (Black patients with any type of endometrial cancer compared with White cases, HR 1.43, 95% CI, 1.13–1.83) (Table 6). Notably, this pattern persisted among cases with low grade EEC (Black compared with White cases, HR 2.26, 95% CI, 1.41–3.64) and for patients who presented with regional/distant disease (Black compared with White cases, HR 1.62, 95% CI, 1.15–2.28). In contrast, there were no differences in mortality risk for Asian, Pacific Islander or Hispanic patients when compared with White patients.

Discussion

Prior publications have demonstrated increased rates of aggressive endometrial cancer histologies (non-EEC) in Black patients and associated worse survival [4, 12, 19]. Access to care has been postulated as a possible reason for worse survival in Black patients [23, 24] which prompted our inquiry into the ACTUR, a repository for data collected from patients treated in the Military Health System where access to care is universal. This study reaffirmed these trends in endometrial cancer including higher rates of non-EEC and high-grade histology in Black women [13, 14].

A novel finding in our study was that a higher percentage of Pacific Islander endometrial cancer patients received adjuvant therapy amongst all racial and ethnic groups and this persisted in most subgroup analyses. We did not however observe any consistent pattern of more aggressive endometrial tumor characteristics for Pacific Islander patients. The design of this study is better positioned to demonstrate differences in the receipt of adjuvant therapy because prior analyses have either not included Pacific Islander populations or have aggregated Pacific Islander with Asian patients [14, 25]. Including Asian and Pacific Islander patients together could mask aggressive endometrial cancer characteristics among the Pacific Islander population. In contrast, Asian women have been found to have similar rates of low grade tumors and EEC histology as White cases [26] and have improved overall and cancer-specific survival compared to other racial and ethnic groups [6] [26]. In the current study Asian women were more likely to have low grade tumors and EEC histology. We noted increased use of adjuvant treatment in Asian patients which is difficult to reconcile but, may be due to their increased presentation with more regional or distant stage disease. Regardless, it is of interest to further evaluate why a higher proportion of Pacific Islander patients received adjuvant treatment.

In the current study we observed that Black endometrial cancer patients had a higher risk of all cause mortality as compared with White patients. Inquiry into SEER and National Cancer Data Base (NCD) have reported similar increased mortality risk in Black women compared to White women across all ages [11, 27]. The SEER inquiry compared the patient’s age at diagnosis in relation to presentation with non-EEC tumors in Black and White women and they observed a trend toward increasing non-EEC histology in older women with a more pronounced increase for Black patients. In the review of ACTUR data presented here, there was concordance with the SEER data with no statistically significant difference in the proportion of cases with non-EEC in young women (< 50 years old) by race/ethnicity. However, there was a higher proportion of non-EEC histology in Black patients over the age of 50 compared to other racial and ethnic groups. There remain unknown drivers of aggressive disease that affect Black women variably.

Histologic typing of endometrial cancer has helped to dichotomize less aggressive (EEC) and more aggressive (non-EEC) disease however, molecular profiling has been tipped to add further stratification of aggressive disease. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) has been queried to investigate variance in molecular profiles of endometrial cancer and its association with outcome disparities. EEC is associated with microsatellite instability and mutations in PTEN, PIK3CA, KRAS, POLE and CTNNBI whereas non-EEC is associated with TP53, ARID1A and HER2 overexpression for example [4]. Another study evaluated differences in endometrial cancer molecular profiles between ethnicities and found that Black or African American women were more likely to harbor TP53 mutations (49%) versus White or Asian women who most often had mutations in PTEN (63% and 85%, respectively) [9]. As this data accumulates and molecular data continues to be used to drive treatment in oncology there is hope that a more targeted approach may be useful to address disparities in endometrial cancer.

Limitations of this study include small sample size when stratifying by racial and ethnic groups which may have limited our ability to identify meaningful differences in subgroups (age < 50 years in particular). Hispanic patients constituted a small subgroup in this study and when viewed in comparison to other groups represented a middling risk profile however, with increased power we could have better characterized these patients. In the ACTUR there were three methods of race and ethnicity reporting; two of the methods were based on self-report from the patient while the third method involved physician reports. Physician reported race and ethnicity is less reliable than self-reports from the patients. This could lead to misclassification of race and ethnicity and may attenuate risk estimates towards the null. Another limitation was the difficulty in stratifying on race and ethnicity as the groups included in this study cannot capture the diversity they represent (e.g., Pacific Islander: Native Hawaiian, Guamanian or Chamorro, Tongan, etc.). Furthermore, data were unavailable on body mass index, smoking status and on variables that are required to define the receipt of guideline concordant treatment [including detailed information on primary treatment (type of surgery, adjuvant treatment) and International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging]. Our study relied on registry data obtained by pathology reports generated at multiple sites which could lead to imprecise classification of histologic subtypes. It would therefore be useful to confirm these results in studies that have implemented a centralized pathology review. The primary strength of this study is that the Pacific Islander population was included and queried.

In summary, we observed more aggressive tumor features (non-endometrioid and high-grade histology) in Black patients and a higher proportion of Pacific Islander patients received adjuvant therapy. It has been hypothesized that differences in access to care may contribute in part to the observed racial and ethnic disparities in endometrial cancer mortality. Thus our goal was to determine whether there were differences in mortality risk across racial and ethnic groups in an equal access to care environment. Compared with White endometrial cancer patients, Black patients had a 1.4-fold higher risk of all cause death; these differences in mortality risk persisted in our US Military system study population where patients have equal access to healthcare. This supports the hypothesis that factors other than access to care may contribute to the observed racial and ethnic disparities in endometrial cancer mortality.

Data Availability

This study used data from the data from the U.S. DoD ACTUR database which are not publically available due to privacy concerns. Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A, Cancer Statistics (2021) CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33. Epub 2021/01/13. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654. PubMed PMID: 33433946

Siegel RL, Miller K, Jemal A (2021) Cancer Facts & Figs. In: Society AC, editor. 2021

Kaaks R, Lukanova A, Kurzer MS (2002) Obesity, endogenous hormones, and endometrial cancer risk: a synthetic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 11(12):1531–1543 Epub 2002/12/24. PubMed PMID: 12496040

Lu KH, Broaddus RR, Endometrial Cancer (2020) N Engl J Med 383(21):2053–2064 Epub 2020/11/19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1514010. PubMed PMID: 33207095

Setiawan VW, Yang HP, Pike MC, McCann SE, Yu H, Xiang YB et al (2013) Type I and II endometrial cancers: have they different risk factors? J Clin Oncol 31(20):2607–2618 Epub 2013/06/05. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.48.2596

Clarke MA, Devesa SS, Harvey SV, Wentzensen N (2019) Hysterectomy-corrected uterine Corpus Cancer Incidence Trends and differences in relative survival reveal racial disparities and rising rates of nonendometrioid cancers. J Clin Oncol 37(22):1895–1908 Epub 2019/05/23. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.00151

Giaquinto AN, Miller KD, Tossas KY, Winn RA, Jemal A, Siegel RL (2022) Cancer statistics for african American/Black people 2022. CA Cancer J Clin 72(3):202–229 .21718. PubMed PMID: 35143040

Huang AB, Huang Y, Hur C, Tergas AI, Khoury-Collado F, Melamed A et al (2020) Impact of quality of care on racial disparities in survival for endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 223(3) Epub 2020/02/29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.021. 396 e1- e13

Guttery DS, Blighe K, Polymeros K, Symonds RP, Macip S, Moss EL (2018) Racial differences in endometrial cancer molecular portraits in the Cancer Genome Atlas. Oncotarget 9(24):17093–17103 Epub 2018/04/24. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.24907

Rodriguez VE, LeBron AMW, Chang J, Bristow RE (2021) Guideline-adherent treatment, sociodemographic disparities, and cause-specific survival for endometrial carcinomas. Cancer 127(14):2423–2431 Epub 2021/03/16. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33502

Tarney CM, Tian C, Wang G, Dubil EA, Bateman NW, Chan JK et al (2018) Impact of age at diagnosis on racial disparities in endometrial cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol 149(1):12–21 Epub 2017/08/13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.07.145

Cote ML, Ruterbusch JJ, Olson SH, Lu K, Ali-Fehmi R (2015) The growing Burden of Endometrial Cancer: a major racial disparity affecting Black Women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 24(9):1407–1415 Epub 2015/08/21. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0316

Oliver KE, Enewold LR, Zhu K, Conrads TP, Rose GS, Maxwell GL et al (2011) Racial disparities in histopathologic characteristics of uterine cancer are present in older, not younger blacks in an equal-access environment. Gynecol Oncol 123(1):76–81 Epub 2011/07/12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.06.027

Park AB, Darcy KM, Tian C, Casablanca Y, Schinkel JK, Enewold L et al (2021) Racial disparities in survival among women with endometrial cancer in an equal access system. Gynecol Oncol. Epub 2021/07/31. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.07.022. PubMed PMID: 34325938

Lin J, Hu H, Shriver CD, Zhu K (2022) Survival among breast Cancer patients: comparison of the U.S. Military Health System with the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End results Program. Clin Breast Cancer 22(4):e506–e16 PubMed PMID: 34961733

Lin J, Kamamia C, Brown D, Shao S, McGlynn KA, Nations JA et al (2018) Survival among Lung Cancer Patients in the U.S. Military Health System: a comparison with the SEER Population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 27(6):673–679 Epub 2018/03/14. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-17-0822

Dew A, Darmon S, Lin J, Ware J, Roswarski JL, Shriver CD et al (2022) Survival among patients with multiple myeloma in the U.S. military health system compared to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and end results (SEER) program. J Clin Oncol 40(16suppl):6524. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.6524

Grambsch P, Therneau T (1994) Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 81:515–526

Felix AS, Brasky TM, Cohn DE, Mutch DG, Creasman WT, Thaker PH et al (2018) Endometrial carcinoma recurrence according to race and ethnicity: an NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group 210 study. Int J Cancer 142(6):1102–1115 Epub 2017/10/25. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31127

Nichols HB, Schoemaker MJ, Wright LB, McGowan C, Brook MN, McClain KM, in the National Cancer Institute Cohort Consortium (2017) The premenopausal breast Cancer collaboration: a Pooling Project of Studies participating. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 26(9):1360–1369 Epub 20170609. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-17-0246

Feskanich D, Hankinson SE, Schernhammer ES (2009) Nightshift work and fracture risk: the Nurses’ Health Study. Osteoporos Int 20(4):537–542 Epub 2008/09/04. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-008-0729-5

Team RC (2021) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria

Bregar AJ, Alejandro Rauh-Hain J, Spencer R, Clemmer JT, Schorge JO, Rice LW et al (2017) Disparities in receipt of care for high-grade endometrial cancer: a National Cancer Data Base analysis. Gynecol Oncol 145(1):114–121 Epub 2017/02/06. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.01.024

Sud S, Holmes J, Eblan M, Chen R, Jones E (2018) Clinical characteristics associated with racial disparities in endometrial cancer outcomes: a surveillance, epidemiology and end results analysis. Gynecol Oncol 148(2):349–356 Epub 2017/12/26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.12.021

Kost ER, Hall KL, Hines JF, Farley JH, Nycum LR, Rose GS et al (2003) Asian-pacific Islander race independently predicts poor outcome in patients with endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 89(2):218–226 Epub 2003/04/26. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00050-7

Mahdi H, Schlick CJ, Kowk LL, Moslemi-Kebria M, Michener C (2014) Endometrial cancer in asian and american Indian/Alaskan native women: tumor characteristics, treatment and outcome compared to non-hispanic white women. Gynecol Oncol 132(2):443–449 PubMed PMID: 24316310

Mukerji B, Baptiste C, Chen L, Tergas AI, Hou JY, Ananth CV et al (2018) Racial disparities in young women with endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 148(3):527–534 Epub 2018/01/09. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.12.032

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Michele Beck and John McGeeney who assisted with extracting data from the ACTUR database for this study.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Daniel Desmond, Zhaohui Arter, Jeffrey Berenberg and Melissa Merritt contributed to the study conception and design. Daniel Desmond, Zhaohui Arter and Jeffrey Berenberg assisted with the acquisition of data. Data analysis was performed by Melissa Merritt. All of the authors interpreted the results of the data analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Daniel Desmond and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

The authors certify that the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The Tripler Army Medical Center committee has approved this study as Exempt Human Subjects research.

Consent to participate

This is an observational study involving analysis of secondary data only. There was no direct interaction with human subjects for this study.

Disclaimer

The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS), the Department of Defense (DoD) or the Departments of the Army, Navy, or Air Force.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Desmond, D., Arter, Z., Berenberg, J.L. et al. Racial and ethnic differences in tumor characteristics among endometrial cancer patients in an equal-access healthcare population. Cancer Causes Control 34, 1017–1025 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-023-01716-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-023-01716-9