Abstract

Purpose

Updated evidence for the treatment of obesity in cancer survivors includes behavioural lifestyle interventions underpinning at least one theoretical framework. The aim of this systematic review was to assess the effectiveness of theory-based lifestyle interventions for the treatment of overweight/obesity in breast cancer survivors and to report effective behavioural change techniques (BCTs) and components used in these interventions.

Methods

Four databases were searched for RCTs published between database inception and July 2022. The search strategy included MeSH terms and text words, using the PICO-framework to guide the eligibility criteria. The PRISMA guidelines were followed. Risk-of-bias, TIDier Checklist for interventions’ content, and the extent of behaviour change theories and techniques application were assessed. To evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, trials were categorised as “very,” “quite,” or “non” promising according to their potential to reduce body weight, and BCTs promise ratios were calculated to assess the potential of BCTs within interventions to decrease body weight.

Results

Eleven RCTs met the inclusion criteria. Seven trials were classified as “very”, three as “quite” and one study was “non” promising. Studies’ size, design, and intervention strategies varied greatly, but the weight-loss goal in all studies was ≥ 5% of the initial body weight through a 500–1000 kcal/day energy deficit and a gradually increased exercise goal of ≥ 30 min/day. Social Cognitive Theory was the most commonly used theory (n = 10). BCTs ranged from 10 to 23 in the interventions, but all trials included behaviour goal setting, self-monitoring, instructions on the behaviour, and credible source. The risk-of-bias was “moderate” in eight studies and “high” in three.

Conclusion

The present systematic review identified the components of theory-based nutrition and physical activity behaviour change interventions that may be beneficial for the treatment of overweight/obesity in breast cancer survivors. The strategies mentioned, in addition to reported behavioural models and BCTs, should be considered when developing weight-loss interventions for breast cancer survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obesity has been suggested as an independent risk factor for breast cancer prognosis [1, 2]. Greater body mass index (BMI) and adiposity are linked to adverse outcome in women with breast cancer, including increased risk of recurrence and mortality, in addition to poorer quality of life and increased risk of developing co-morbidities, such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease [2,3,4,5,6]. However, observational studies have shown that lifestyle modification, especially the improvement of nutrition and physical activity, would potentially benefit breast cancer survival along with improvements in metabolic parameters and reduction in the risk of co-morbidities [3, 6].

Patients after cancer diagnosis seem to have higher level of motivation to change their lifestyle behaviours than they had before cancer diagnosis [7,8,9]. Interventions that promote healthy nutrition and physical activity have been proposed as an effective approach to support cancer survivors in lifestyle modification and weight loss [10, 11]. Current guidelines suggest that lifestyle modification could be successfully implemented through behavioural interventions [11, 12], especially when these are designed according to theoretical frameworks [13, 14]. Over the past years, many theories and models have been described in the literature, with Cognitive Behavioural Theory [15], Social Cognitive Theory [16] and the Transtheoretical Model [17] being the most commonly used theories in dietetic practice. Theory-based interventions facilitate an understanding of mechanisms of behaviour change providing the basis for developing more effective interventions [18]. This can be addressed by identifying the factors that influence behaviour called determinants, and select the appropriate behaviour change techniques to target behaviour [19]. Recent studies indicate that interventions delivered by credentialed healthcare professionals who are using behaviour change techniques may be more effective in improving patient health outcomes than dietary interventions which are not developed based on behavioural theories [13]. Effective behavioural change techniques in interventions for cancer survivors include goal setting, problem solving and social support [9].

Τhe implementation of lifestyle interventions in breast cancer survivors, however, is still limited [2, 12]. The majority of previous literature reviews focusses on the impact of body weight loss on breast cancer survival, without taking into account the methods used to achieve lifestyle modification or describing the treatment mechanisms and/or the behaviour change techniques used to successfully treat overweight/obesity in breast cancer survivors [1, 2, 4, 5]. Although there are few reviews focussing on lifestyle interventions in cancer survivors [2, 12, 20], reviews addressing breast cancer are scarce. Some reviews examine either the dietary [7, 21, 22], or the physical activity [21, 23,24,25] interventions, but not the combination of both lifestyle behaviours on weight control. A recently published review [26] focussed on weight-loss interventions in breast cancer survivors targeting different behaviours, such as ‘diet’, ‘exercise’, ‘psychosocial support’ and/or their combinations. Although all the interventions included resulted in a reduction in BMI, the subgroup analyses showed that interventions that combined multiple factors, such as ‘diet and exercise’ or ‘diet, exercise and psychosocial support’, led to greater improvements in anthropometric indices and weight status compared to ‘diet’-only interventions. Despite the fact that this systematic review and meta-analysis rigorously examines various elements and/or their combinations on weight loss in breast cancer survivors, the study does not focus on the interventions’ constructs and BCTs, which could facilitate behaviours modification, since this was not within their scope. Finally, even less reviews have examined the effectiveness of weight-loss intervention in breast cancer survivors based on their theoretical framework [22, 24, 25]. Given that multifactorial interventions may be more effective in managing body weight, identifying the elements and BCTs used in the most effective interventions may result in the greatest benefit in this population.

The aim of this systematic review was to assess the effectiveness of theory-based lifestyle interventions for the treatment of overweight/obesity in breast cancer survivors and to report effective behavioural models and strategies used in these interventions.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [27], and a PRISMA checklist is provided.

It has also been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO (CRD42021252827).

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The targeting population was female, adult, breast cancer survivors with BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 and without any active cancer therapy or any ongoing treatment, except of hormonal or immune therapy. The eligible interventions included both dietary and physical activity components targeting overweight/obesity with the use of at least one behaviour change theory or model. Randomized Control Trials (RCTs) with at least one control or comparison group of weight-loss interventions were eligible for inclusion. Original articles/studies published in English language, between database inception and July 2022 were included.

Animal studies, pharmacological studies, non RCT studies, RCTs not published in English, trials with breast cancer survivors with active cancer, trials without a specific theoretical framework such as lifestyle interventions with behavioral counselling in general, conference proceedings, letters, reviews or meta-analyses were excluded.

In this review, breast cancer survivors were defined as women who have received a diagnosis of breast cancer and having completed overall treatment, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and other cancer treatments, excluding hormone or immune therapy.

Search methods

A structured search was conducted, focussing on the 4 following databases: PubMed/Medline, Scopus, TripDatabase and Central/Cochrane. The search strategy included Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and text words. These terms were related to behavioural interventions, breast cancer survivors, obesity/overweight, and weight loss/BMI reduction, using the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) framework to guide the eligibility criteria. Consistently, the following terms were combined: (Breast Neoplasm OR breast cancer OR breast cancer survivors) AND (lifestyle intervention OR behavioural intervention OR behavioural intervention OR theory-based intervention OR theoretical framework) AND (obesity OR overweight) AND (weight loss OR weight-loss OR weight change OR weight management OR BMI reduction). No date, country or origin/ethnicity restrictions were applied. Publications were imported in Endnote, where data were checked, duplicates were removed, and the title and the abstract were screened. Additionally, reference lists of RCT studies were cross-matched and forward citation searching was conducted to detect additional studies that met the inclusion criteria. Moreover, the International Trials Registry was explored for ongoing trials. After the title screening, the remaining publications (n = 280) were uploaded in the Rayyan application [28] to complete the abstract screening process and the full-text review.

The research in the databases and the screening of the publications were independently implemented by two reviewers (M.P. and D.S.). Any disagreements during the screening process were discussed between M.P. and D.S and resolved through consultation with O.A.

The full search strategy is detailed in supplemental file 1.

Data extraction

Data on study characteristics (author, publication year, title, study design and duration), participants’ characteristics (age, BMI), cancer site, study groups, intervention duration, lifestyle modifications, behavioural change model and weight change outcome were extracted. Information was collected from both the original articles (the included publications) along with any protocol/study design, previous or subsequent publication of each study. Data were checked by three reviewers (M.P., D.S., C.C.).

Interventions’ description was recorded by M.P. using the TIDier (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) Checklist, including 12 categories “brief name”, “why”, “what (materials)”, “what (procedures)”, “who provided”, “how”, “where”, “when and how much”, “tailoring”, “modifications”, “how well (planned)” and “how well (actual)” [29]. Total set of TIDier Checklist is included in supplemental file 2.

The Theory Coding Scheme [30] was used to evaluate the way in which behavioural theory has been applied within interventions. The final Theory Coding Scheme comprises 19 items, of which items 1–11 assess how theory and targeted constructs were used to developing the intervention, while items 12–19 evaluate methodological issues concerning the use of theory in the basis of the study outcomes. Provided that one of the aims in this systematic review was to appraise the application of theory to interventions, we decided to code items 1–11 and exclude items 12–19. The included studies were examined for the use of their theoretical framework only by one reviewer (M.P.) according to the main publication about the development of Coding Theory [30] and definitions related to theoretical constructs [18, 19, 31,32,33]. To facilitate the coding, a record was created between the targeted theoretical constructs and the intervention techniques of each trial, and is available in supplemental file 2, along with the results of the Theory Coding Scheme.

The Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy [34] was used to identify the behaviour change techniques (BCTs) in the interventions. This taxonomy consists of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques which are utilised for specifying the active elements of behavioural change interventions. Each study was independently coded by two reviewers (M.P. and D.S.) and the disagreements were discussed and resolved through the third reviewer (C.C). The three reviewers (M.P., D.S. and C.C.) totally agreed to the final selection of BCTs for all the studies and were assisted by the definitions given from the main publication and supplementary material of the taxonomy along with the theoretical understanding of intervention evaluations [18, 19]. The BCTs taxonomy mapping of the studies is presented in supplemental file 2.

Data synthesis

Given the wide variety of the interventions’ content and design as well as the aims of this review, a meta-analysis was not appropriate. As a result, a narrative synthesis of the content and the promise of the interventions (based on criteria used in previous reviews by Gardner et al. and Moore et al.) was used as guidance for the development of more effective future interventions [35, 36].

Interventions’ content was assesses using the TIDier (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) Checklist [29]. Total set of TIDier Checklist is included in supplemental file 2.

Interventions’ promise classification system as described by Gardner [35] was used to assess the effectiveness of each study. According to this method, interventions were grouped into three categories of “promise” depending on their potential post-intervention reductions in participants’ body weight (statistically significant within and/or between group). Interventions were considered “very promising” if there were statistically significant reductions in participants’ body weight within the intervention group, and this reduction was greater than observed in at least one comparator arm (control group or at least one other intervention group). Interventions were considered “quite promising” if there were either statistically significant reductions in participants’ body weight within the intervention group, or reduction in at least one comparator arm. Interventions were considered “non-promising” if no statistically significant decreases were found neither within intervention arm nor between study arms. This classification ensured that studies with the strongest evidence of their efficacy were distinguished from those with weaker evidence. Interventions’ promise was estimated independently by two reviewers (M.P., C.C.).

The potential of BCTs within interventions for facilitating weight loss was calculated with a “promise ratio” for each BCT. The “promise ratio” of a BCT is defined as the ratio of the number of “very promising” and the number of “quite promising” interventions in which this BCT was present, divided by the number of “non-promising” interventions of which this BCT was a component. BCTs were considered as promising if there were featured in at least twice as many “promising” (very and quite) as “non-promising” interventions (promise ratio ≥ 2). BCTs found in two or more “promising” interventions but in none “non-promising” intervention were reported as the number of “promising” interventions in which a BCT featured and not as a ratio. A promise ratio was not calculated if only appeared in non-promising interventions or only appeared once. The higher the ratio, the more promising the BCT.

Risk of bias assessment

The revised version of Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) [37] was implemented for the included studies, examining the following five bias domains: randomization process; deviations from intended interventions; missing outcome data; measurement of the outcome; and selection of reported results. The robvis tool was used to visualize risk of bias assessment [38].

Each study was assessed independently by two reviewers (M.P. and D.S.) using the up-to-date information from the developers on RoB 2 such as the full guidance document and the key Cochrane resources for using RoB 2. Any discrepancies between them were resolved through discussion, and the final decision was made with their mutual consent. The overall risk of bias were defined as “low” or “high” or expressed as “some concerns” according to the assessment technique set out in the aforementioned tool and based on these criteria each study was rated as either “Low risk of bias” (for all domains), “Some concerns” (at least one domain raised some concerns but none high risk at any domain) or “High risk of bias” (at least one domain with high risk of bias or some concerns in multiple domains).

Inter-rater agreement

Inter-rater agreement was calculated for BCTs taxonomy, risk of bias assessment, and interventions’ promise classification, using percentage agreement and kappa (κ) (0–0.20 = slight agreement, 0.20–0.40 = fair agreement, 0.40–0.60 = moderate agreement, 0.60–0.80 = substantial agreement, and > 0.80 = nearly perfect agreement) [39].

Results

Search results

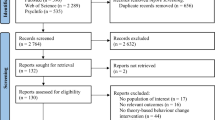

Database searches yielded a total of 1869 articles from Medline (n = 281), Scopus (n = 220), Tripdatabase (n = 1226), and Central/Cochrane (n = 142). Screening the references list, ten additional articles were found. After duplicates were removed, a total of 1643 articles were screened by title and abstract, with 73 articles being selected for full-text screening. Eleven RCT studies were included in this systematic review, meeting the inclusion criteria [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. The remaining 62 articles were excluded for a variety of reasons, including study design publication (n = 11), lack of theory-based interventions (n = 16), participants’ BMI < 25 kg/m2 (n = 3), non-RCT studies (n = 6), not weight loss as an outcome (n = 25), and pharmacological RCT (n = 1). The search results and selection process have been presented in the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram (Fig. 1). The full search strategy and the excluded studies are detailed in supplemental file 1.

Studies’ characteristics and content

Interventions differed greatly regarding the number of samples, with the ENERGY trial [40] including the most participants (n = 692) and the Stepping Stone study [44] including the fewest. Three studies [46, 49, 50] included approximately 300 participants, while the remaining six [41,42,43, 45, 47, 48] had less than 100 samples.

The main characteristics (sample, design, intervention, lifestyle modification goals, outcome goal) of the eleven studies are summarized in Table 1. For the extraction of the results, any protocol [51,52,53,54], and any previous or subsequent publication [55,56,57,58] of each study was taken into account.

Interventions’ content were recorded using TIDier Checklist in Table 2.

Interventions design and strategies

Interventions varied in their study design, but all of them had a control group. Specifically, most of them, seven of the eleven studies, had a 2-arm design [40, 42, 44, 46,47,48, 50] which means an intervention group and a control or a comparison group. Two of the studies had a 3-arm design [41, 45]. Specifically, in Dames trial [41]), a study involving 68 dyads of mothers breast cancer survivors and their daughters, the three groups included were the individual, the team (mothers and daughters) and the control group. The intervention given was the same for the individual and the team group, but in the first group a tailored diet and exercise were delivered individually to mothers and daughters while in the second group the intervention was given as a team, emphasising to the mother-daughter bond. In the LEAN study [45], 100 breast cancer survivors were divided into three groups: an in-person counselling group, a telephone counselling group and the control group. The intervention was the same for the counselling groups but it was given in a different manner, in-person or telephone-delivered. Finally, two studies had a 4-arm design [43, 49]. In the trial of Djuric et al., 48 breast cancer survivors were randomly assigned to one of the four groups: control, the commercial Weight Watchers program (WW), individualised counselling or a combination of the WW program and the individualised counselling. In the Wiser trial of Schmitz et al., 351 breast cancers survivors were randomized to either control or home-based exercise intervention or weight-loss intervention or the combined intervention (exercise and weight-loss). Every of these interventions was different to each group, as described in Table 1.

Most weight-loss interventions (n = 9) lasted 6 months [40, 41, 43, 45,46,47,48,49,50], except of one which lasted 16 weeks [42], and the Stepping Stone study whose length of duration was 12 weeks [44]. All the studies reported a follow-up phase.

Studies used a combination of widely different interventions strategies, such as in-person, telephone or mailed delivered interventions implementing either in group or individual sessions, including telephone contact, text messages, web-based platform and/or email guidance via newsletters. In more detail, in-person group sessions were included in four studies [40, 42, 44, 46], individual telephone sessions were included in three studies [47, 48, 50], in-person group meetings along with telephone individual counselling were used in two studies [43, 49], either in-person or telephone individual sessions was delivered in one study [45], and mailed intervention was delivered in one study [41]. As mentioned above, interventions’ strategies included in addition telephone contact [40, 42, 44], text messages [46, 48], web-based learning platform [47], and newsletters [40, 41, 46, 48, 50].

Self-Monitoring was the most common element of behaviour modifications in every intervention and it was implemented in all studies with food records or diaries and exercise logs. Many other tools of self-monitoring were utilised as well, including pedometers or shoes chips to record the daily steps [40,41,42,43,44,45, 48, 50], weight records [40, 45,46,47,48, 50], notebooks/workbooks/worksheets/booklets with educational material [40,41,42,43,44,45, 47,48,49,50], class activities [46], web-based resources [40, 41, 47], and digital videos [40].

Lifestyle modification

All the studies reported that weight loss interventions were developed with two main target behaviours: dietary and physical activity modifications.

Concerning the dietary modifications, the studies targeted firstly on an energy intake reduction and secondly on the diet quality and a healthier eating behaviour.

Upon these, seven to eleven studies reported a 500–1000 kcal daily energy deficit [40, 42, 43, 45, 46, 48, 50]. In two studies [47, 49] the energy intake depended between 1200 and 2200 kcal/day. Specifically, in Power-remote trial [47] the energy intake was 1200–2200 kcal/day depending on the initial body weight, and in Wiser trial [49] the daily caloric intake was restricted to 1200–1500 kcal/day. Finally, in two studies [41, 44] a reduced energy intake was reported without specifying the energy restriction. Extensively, in the Dames trial [41] dietary modification was either directed to lower-calorie substitutes or provided with guidance on portion control, but in the Stepping stone study [44] it was only reported a modification of diet to promote approximately 1 lb of weight loss per week, without any further details mentioned.

Healthier eating modifications varied between the eleven studies. Nine studies recommended increased daily intake of fruits and vegetables [40, 42,43,44, 46,47,48,49,50], and in six studies the recommendation was specified in at least 5 or more servings of fruits and vegetables per day [43, 44, 46,47,48,49]. Similarly, six studies recommended an increment in daily fibre or grains intake [40, 42, 43, 45, 49, 50]. Seven of the studies targeted reduction in fat intake with a dietary fat goal of at least < 35% of total energy intake [43,44,45,46,47,48, 50]. Just one study recommended a decrease in sugar consumption [45].

Physical activity modifications were implemented through various guidelines. All studies recommended an increase in aerobic exercise and four of them targeted on a daily goal of 10,000 steps [40, 44, 45, 48]. Seven of the studies additionally included strength training [40,41,42, 46, 48,49,50], of which five of them specified a muscle strengthening goal of at least 2 times per week [40,41,42, 48, 49]. Four studies suggested an increase in daily lifestyle physical activity [40, 42, 43, 48]. A progressive exercise intervention with a step-wise increase in time and intensity of physical activity was recommended by eight of the studies [40, 42, 45,46,47,48,49,50].

Each study determined its aerobic exercise goal differently; thus, in six studies, the aerobic exercise goal was approximately 150–200 min per week [41, 44,45,46, 49, 50], whereas in five studies, it was > 200 min minutes per week [40, 42, 43, 47, 48].

It is worth mentioning that 82% of the studies (n = 9) reported that dietary and/or exercise recommendations were in agreement with the official guidelines of several international organisations [40, 41, 43,44,45,46,47,48, 50].

Body weight change goal

Nine of the eleven studies reported a specific weight loss goal ranging between 5–10% of the initial body weight [40, 43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50], while in the remaining two studies the outcome goal was targeted at any body weight reduction [41, 42]. The final outcomes for the weight loss of each study are shown in Table 3.

Risk of bias

From the ten included studies, none had low risk of bias, three of them found at high risk and eight studies arose some concerns considering the bias. Two domains were judged to have low risk of bias in all studies, namely bias due to missing outcome data and bias in measurement of the outcome. Bias arising from the randomization process was found to be low in nine to eleven studies, while bias in selection of the reported result was found to be low in eight to eleven studies. Bias due to deviations from intended interventions was judged high risk in two studies and of some concerns in the remaining studies. Lack of blinding of participants and assessors to the interventions and non-appropriate analysis used to estimate the effect of assignment to the intervention were the most common sources of potential bias across the studies. Risk of bias judgement for each study is included in Fig. 2 [38] and in detail in supplemental file 3. Excep for the included papers, any protocol and any previous or subsequent publication of each study were considered for the extraction of results. Inter-rater reliability was substantial (61.3%; κ = 0.694, p < 0.001).

Results of synthesis

Intervention promise

Seven studies were classified as “very promising” [42, 43, 45, 46, 48,49,50], three studies as “quite promising” [40, 41, 47], and only one study as “non-promising” [44]. Inter-rater agreement was moderate (81.8%; κ = 0.593, p < 0.004).

The “very promising” category included five of the eight studies with some concerns in the risk of bias assessment and two of the three studies with high bias, as shown in Table 3. The “quite promising” studies included three trials with some concerns about bias, while the “non-promising” study had a high bias. The heterogeneity of the studies’ characteristics discourages effective comparisons between the different categories of interventions’ promise.

Behaviour change theory

The most common theoretical framework used was Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) in ten studies, either alone [43, 45, 47, 48, 50] or in combination with other theoretical models [40, 41, 44, 46, 49]. In the ENERGY trial [40], SCT was combined with the Cognitive Behavioural Treatment of Obesity (CBT-OB), which includes cognitive therapy techniques with the goal of optimising maintenance of weight loss. In Dames trial [41], SCT was combined with the Transtheoretical Model of Change (TTM), while in the Stepping Stone study [44] with the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB). Finally, the Socio-Ecological Model (SEM) was additionally used in the Moving Forward trial [46], and the Behavioural Self-Management Theory in the Wiser trial [49]. Seven of the aforementioned studies [40, 44, 46,47,48,49,50] utilised strategies of behavioural weight loss programs, such as the Motivational Interviewing Technique (MIT).

Only one study, the Healthy Weight Management (HWM) study [42] was guided by the Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and its components.

According to the coding of the Theory Coding Scheme, all trials mentioned the targeted theoretical constructs relevant to behaviour (item 2) and their correlation with the intervention techniques (items 7–9, 11), contrariwise no trials selected participants based on theory-related constructs (item 4). Additionally, 10 trials [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49] reported using theory to select or develop the intervention (item 5) and 7 trials [40,41,42,43,44,45, 50] to tailor the intervention to the needs of the participants (item 6). Finally, 9 trials [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48] linked all theory-relevant constructs to at least one intervention technique (item 10).

Behaviour change techniques (BCTs)

The studies varied widely in the techniques used to implement their interventions, which complicated the mapping of BCTs. Forty-two different BCTs were identified across the eleven studies. Based on the BCT taxonomy classification studies included in this review used 10–23 BCTs. The “very promising” interventions included 11–23 BCTs, the “quite promising” between 10 and 20 BCTs and the “non-promising” intervention included 14 BCTs. As shown in Table 4, the “promising” (very and quite) studies used mainly the following BCTs: In ten studies, 1.1 Goal setting (behaviour), 2.3 Self-monitoring of behaviour, 4.1 Instruction on how to perform the behaviour, and 9.1 Credible source; in nine studies, 1.2 Problem solving, and 2.2 Feedback on behaviour; in eight studies, 1.3 Goal setting (outcome), and 8.7 Graded tasks; in seven studies, 1.4 Action planning, and 6.1 Demonstration of the behaviour, and in six studies, 2.4 Self-monitoring of outcome(s) of behaviour.

Details of the BCTs used in each study are included in supplemental file 2. Inter-rater agreement was almost perfect (98%; κ = 0.929, p < 0.001).

Discussion

In this systematic review, the elements of the included interventions, such as intervention strategy (duration, sessions, tools), behaviour change models and techniques, behavioural components (diet and exercise goals) and primary outcomes (weight loss goal) were recorded. Studies differed significantly in terms of sample size, design, and interventions, but the dietary, physical activity, and weight loss goals were consistent across all trials. Interventions with larger sample sizes were assumed to be less biased and more promising. According to the findings of the present study, the “promising” interventions [40,41,42,43, 45,46,47,48,49,50] were more likely to include all or most of all of the aforementioned characteristics. Specifically, it was observed that the “promising” behavioural interventions treating obesity in breast cancer survivors had a six-month duration of treatment, followed by in-person group or individual sessions, either individual telephone sessions, or their combination. The weight loss target was at least 5% of the initial body weight, through a 500–1000 kcal daily energy deficit, tailored according to patients’ personalized energy needs. Behavioural modification aimed to increase consumption of fruits, vegetables and fibre and to reduce dietary fat along with a gradually increased exercise goal of at least 30 min per day. Self-monitoring was identified as the most important mediator of behavioural modification with the application of food record, exercise logs and pedometers as the best self-monitoring tools, and complementary tools such as weight records and educational materials. Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) was the theoretical framework that was most commonly used in the effective interventions, while the ten most frequently included behaviour change techniques were behaviour goal setting, self-monitoring of behaviour, instructions on how to perform the behaviour, credible source, problem solving, behaviour feedback, outcome goal setting, graded tasks, action planning, and demonstration of the behaviour.

The findings of the present systematic review are in line with the Weight Loss and Health Goals and Intervention Strategies Guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults [59]. The Expert Panel of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Obesity Society recommend that the most effective behavioural weight loss treatment is an in-person, high-intensity (≥ 14 sessions in 6 months) comprehensive weight loss intervention provided in individual or group sessions by a trained healthcare professional or a nutrition professional, with the following principal components: a moderate reduced-calorie diet designed to induce an energy deficit of ≥ 500 kcal/d, a program of increased physical activity equal to ≥ 30 min/d the most days of the week and, the use of behavioural therapy, and methods such as self-monitoring to facilitate adherence to diet and exercise guidelines [59]. These recommendations suggest that there is evidence to support that comprehensive lifestyle interventions consisting of diet, physical activity, and behavioural therapy result in optimal weight loss in 6 months with frequent, initially weekly sessions in overweight and obese individuals. Furthermore, long-term interventions or a follow-up phase of more than 2 years duration could optimize weight loss maintenance and any potentially benefits on cancer end points [60]. Concerning the mode of interventions’ delivery, the on-site (face-to-face) treatment in group or individual sessions could benefit overweight and obese individuals [59], while telephone-based or smart phone applications interventions that target lifestyle behaviour were found to be effective in cancer survivors [61].

The majority of the studies included in this review had a weight loss target of 5–10% of the initial body weight and are consistent with the findings of other reviews [10, 62]. It has been described that although sustained weight loss of as little as 3–5% of body weight may lead to clinically meaningful reductions in glycemic measures, in blood pressure and in some cardiovascular risk factors, a greater weight loss produces better health benefits [59, 63]. Moreover, the guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults suggest a weight loss goal of 5–10% of baseline body weight within 6 months and continued intervention contact and support after initial weight loss treatment is associated with better maintenance of lost weight [59]. Lifestyle interventions for cancer survivors appear to still focus on outcomes related to diet, fitness and cancer-related psychosocial factors [12]. To determine the behaviours and outcome goals, most of the studies use the recommendations for lifestyle changes, consistent with dietary and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors [64,65,66]. According to these guidelines, adult survivors should aim to exercise at least 150 min per week of moderate to vigorous physical activity above their usual activities, including strength training at least 2 days per week, and adapt a healthy plant-based diet with high consumption of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains to achieve an increased intake of fibre along with limited consumption of processed and red meat. A recent meta-analysis of observational studies in European countries found moderate certainty that adherence to breast cancer guidelines was associated with increased overall and disease-free survival, enhancing the rigorous adoption and implementation of breast cancer guidelines in the clinical setting [67].

Interventions underpinned by behaviour change theories and utilizing various behaviour change techniques were found to be more effective than those not based on any theory. Hence, the use of behaviour change theories and strategies is highly recommended by many official guidelines [3]. The American Dietetic Association encourage health care professionals to practice behavioural therapy for planning effective nutrition counselling interventions [14]. Although, the use of a behavioural therapy is suggested, it remains unclear which theory is the most effective improving the participants’ behaviour, according to a recent review article about the use of behaviour change theories in lifestyle interventions for cancer survivors [22]. In the present review, SCT was the most frequently used theory, similarly to the findings of other reviews of behaviour change interventions targeting obesity in cancer survivors [22, 24, 62]. Michie et al. suggested that using a theory to influence intervention effectiveness should be combined with the appropriate intervention components [30]. Behaviour Change Techniques (BCTs) used in RCTs are auxiliary for the identification of the strategies implemented in each intervention. It has been found that goal setting (1.3), problem solving (1.2) and social support (3.1) along with self-monitoring (2.3) are effective behavioural change techniques to lose weight in a helpful and manageable manner [13, 14]. Additionally with these four BCTs, credible source (9.1), instruction on how to perform the behaviour (4.1) and feedback of behaviour (2.2) were the most commonly used strategies in weight loss interventions for cancer survivors [22, 24, 62]. The importance of the role of a credible source, such as oncology counselor, has been highlighted in providing evidence-based information on the association of breast cancer and diet and physical activity in daily life in developing interventions effectively [68], and additionally in identifying the most important determinants of lifestyle changes in cancer survivors [69]. Moreover, it has been suggested that weight management interventions delivered by healthcare professionals can be effective for weight loss for up to 6 months [70]. The current findings concerning BCTs are in agreement with the aforementioned outcomes.

The findings of the present systematic review should be considered under the light of its strengths and limitations. Regarding the strengths, two independent reviewers performed the selection and the rating process and a third independent reviewer solved any disagreements. Secondly, the PRISMA guidelines for reporting a systematic review were followed [27] and the methodological quality of each study was assessed based on the Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) [37]. Moreover, only RCT studies were included to maximize the quality of the studies being reviewed and the BCT taxonomy was used [34] to code the interventions. This measure makes the behavioural interventions comparable and allows future researchers to review methods used in detail. Regarding the limitations, the included publications were in English language, so non-English articles may have been missed. There is also a high risk of publication bias. All of the included studies were RCTs, and ten to eleven interventions (90.9%) were found “promising” compared to a solely “non-promising” intervention. “Promising” interventions are more likely to be published, which may imply that “non-promising” interventions found in non-RCT trials were not considered in this review, skewing the results. No meta-analysis was conducted in the present review due to the large heterogeneity of the included studies, thus quantitative approaches, such as regression-based assessments for determining whether there is a skew to effect, were not assessed, nor were the moderator effects of publication bias, as is recommended. Since such tests generally assume a single population size effect, inferences of publication bias are dangerous in the face of heterogeneity [71]. Additionally, coding of the theory coding scheme and the behaviour change techniques depended on the reporting quality, quantity and accuracy within the RCTs, and these varied considerably. Although the current review was based on the publications of each study, the majority of the studies referred to a protocol paper and the Authors tried to contact the corresponding authors of the trials that did not have a full description of the intervention [42, 43]. Only one author was reached [43], therefore any details concerning the interventions’ content may be lacking. Finally, in this review is that most studies were rated as having some concerns or a high risk of bias due to the lack of blinding of participants and assessors, suggesting that the body of evidence presented should be carefully considered.

Conclusions

Considering the unique needs of breast cancer survivors, lifestyle interventions should include behavior modifications in diet, physical activity and psychosocial factors according to the official guidelines with the use of behavioural theory and the suitable behavioural change techniques. The completion of the initial cancer treatment signals a critical period, in which breast cancer survivors may adopt healthy behaviours thus maintain or adopt a healthy body weight. The identification of the optimal methods targeting obesity seems vital for lowering the risk of cancer recurrence and overall mortality. The taxonomy can help with the understanding of behaviour change tools used in the interventions; thus, the need for stronger identification of the components of the intervention using a taxonomy of behavioural change techniques should be highlighted. The findings of this systematic review may enable healthcare professionals to include the reported elements and BCTs in their behavioural interventions in order to help breast cancer survivors to improve their lifestyle, control their body weight and maintain the changes more effectively.

Data availability

All datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Jiralerspong S, Goodwin PJ (2016) Obesity and breast cancer prognosis: evidence, challenges, and opportunities. J Clin Oncol 34(35):4203–4216. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.68.4480

Ligibel JA, Basen-Engquist K, Bea JW (2019) Weight management and physical activity for breast cancer prevention and control. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 39:e22–e33. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_237423

Chan DS, Norat T (2015) Obesity and breast cancer: not only a risk factor of the disease. Curr Treat Options Oncol 16(5):22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-015-0341-9

Jackson SE, Heinrich M, Beeken RJ, Wardle J (2017) Weight loss and mortality in overweight and obese cancer survivors: a systematic review. PLoS One 12(1):e0169173. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169173

Lee K, Kruper L, Dieli-Conwright CM, Mortimer JE (2019) The impact of obesity on breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Curr Oncol Rep 21(5):41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-019-0787-1

Vance V, Mourtzakis M, McCargar L, Hanning R (2011) Weight gain in breast cancer survivors: prevalence, pattern and health consequences. Obes Rev 12(4):282–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00805.x

Burden S, Jones DJ, Sremanakova J, Sowerbutts AM, Lal S, Pilling M et al (2019) Dietary interventions for adult cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011287.pub2

Jaffee EM, Dang CV, Agus DB, Alexander BM, Anderson KC, Ashworth A et al (2017) Future cancer research priorities in the USA: a lancet oncology commission. Lancet Oncol 18(11):e653–e706. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30698-8

Ligibel JA, Alfano CM, Courneya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Burger RA, Chlebowski RT et al (2014) American society of clinical oncology position statement on obesity and cancer. J Clin Oncol 32(31):3568–3574. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.58.4680

Lake B, Damery S, Jolly K (2022) Effectiveness of weight loss interventions in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open. 12(10):e062288. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-062288

Ligibel JA, Alfano CM, Hershman D, Ballard RM, Bruinooge SS, Courneya KS et al (2015) Recommendations for obesity clinical trials in cancer survivors: American society of clinical oncology statement. J Clin Oncol 33(33):3961–3967. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.63.1440

Pekmezi DW, Demark-Wahnefried W (2011) Updated evidence in support of diet and exercise interventions in cancer survivors. Acta Oncol 50(2):167–178. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2010.529822

Rigby RR, Mitchell LJ, Hamilton K, Williams LT (2020) The use of behavior change theories in dietetics practice in primary health care: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Acad Nutr Diet 120(7):1172–1197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2020.03.019

Spahn JM, Reeves RS, Keim KS, Laquatra I, Kellogg M, Jortberg B et al (2010) State of the evidence regarding behavior change theories and strategies in nutrition counseling to facilitate health and food behavior change. J Am Diet Assoc 110(6):879–891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2010.03.021

Beck A (1993) Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. Penguin, New York

Bandura A (1998) Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol Health 13(4):623–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870449808407422

Prochaska JO, Norcross JC, DiClemente V (1994) Changing for good: a revolutionary six-stage program for overcoming bad habits and moving your life positively forward. Avon Books Inc, New York

Michie S, Abraham C (2004) Interventions to change health behaviours: evidence-based or evidence-inspired? Psychol Health 19(1):29–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/0887044031000141199

Carey RN, Connell LE, Johnston M, Rothman AJ, de Bruin M, Kelly MP, Michie S (2019) Behavior change techniques and their mechanisms of action: a synthesis of links described in published intervention literature. Ann Behav Med 53(8):693–707. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kay078

Davies NJ, Batehup L, Thomas R (2011) The role of diet and physical activity in breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer survivorship: a review of the literature. Br J Cancer 105(Suppl 1):S52-73. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.423

Spark LC, Reeves MM, Fjeldsoe BS, Eakin EG (2013) Physical activity and/or dietary interventions in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review of the maintenance of outcomes. J Cancer Surviv 7(1):74–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-012-0246-6

Sremanakova J, Sowerbutts AM, Todd C, Cooke R, Burden S (2021) Systematic review of behaviour change theories implementation in dietary interventions for people who have survived cancer. Nutrients. 13(2):612. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020612

Bluethmann SM, Vernon SW, Gabriel KP, Murphy CC, Bartholomew LK (2015) Taking the next step: a systematic review and meta-analysis of physical activity and behavior change interventions in recent post-treatment breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 149(2):331–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-014-3255-5

Liu MG, Davis GM, Kilbreath SL, Yee J (2022) Physical activity interventions using behaviour change theories for women with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv 16:1127–1148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01104-9

Rossi A, Friel C, Carter L, Garber CE (2018) Effects of theory-based behavioral interventions on physical activity among overweight and obese female cancer survivors: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Integr Cancer Ther 17(2):226–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735417734911

Shaikh H, Bradhurst P, Ma LX, Tan SY, Egger SJ, Vardy JL (2020) Body weight management in overweight and obese breast cancer survivors. Cochrane Database System Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012110.pub2

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 339:b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A (2016) Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 5:210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Hoffmann TC, Walker MF, Langhorne P, Eames S, Thomas E, Glasziou P (2015) What’s in a name? The challenge of describing interventions in systematic reviews: analysis of a random sample of reviews of non-pharmacological stroke interventions. BMJ Open 5:e009051

Michie S, Prestwich A (2010) Are interventions theory-based? Development of a theory coding scheme. Health Psychol 29(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016939

Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S (2012) Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci 7:37. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-37

Kwasnicka D, Dombrowski SU, White M, Sniehotta F (2016) Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: a systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychol Rev 10(3):277–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2016.1151372

Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A (2005) “Psychological theory” group: making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 14(1):26–33. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2004.011155

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W et al (2013) The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med 46(1):81–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6

Gardner B, Smith L, Lorencatto F, Hamer M, Biddle SJ (2016) How to reduce sitting time? A review of behaviour change strategies used in sedentary behaviour reduction interventions among adults. Health Psychol Rev. 10(1):89–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2015.1082146

Moore SA, Hrisos N, Flynn D et al (2018) How should long-term free-living physical activity be targeted after stroke? A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 15:100. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0730-0

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I et al (2019) RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 366:l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

McGuinness LA, Higgins JPT (2020) Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): an R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res Syn Meth. 12:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1411

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33(1):159–174 (PMID: 843571)

Rock CL, Flatt SW, Byers TE, Colditz GA, Demark-Wahnefried W, Ganz PA et al (2015) Results of the exercise and nutrition to enhance recovery and good health for you (ENERGY) trial: a behavioral weight loss intervention in overweight or obese breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 33(28):3169–3176. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2015.61.1095

Demark-Wahnefried W, Jones LW, Snyder DC, Sloane RJ, Kimmick GG, Hughes DC et al (2014) Daughters and mothers against breast cancer (DAMES): main outcomes of a randomized controlled trial of weight loss in overweight mothers with breast cancer and their overweight daughters. Cancer 120(16):2522–2534. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28761

Mefferd K, Nichols JF, Pakiz B, Rock CL (2007) A cognitive behavioral therapy intervention to promote weight loss improves body composition and blood lipid profiles among overweight breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 104(2):145–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-006-9410-x

Djuric Z, DiLaura NM, Jenkins I, Darga L, Jen CK, Mood D et al (2002) Combining weight-loss counseling with the weight watchers plan for obese breast cancer survivors. Obes Res 10(7):657–665. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2002.89

Sheppard VB, Hicks J, Makambi K, Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, Demark-Wahnefried W, Adams-Campbell L (2016) The feasibility and acceptability of a diet and exercise trial in overweight and obese black breast cancer survivors: the stepping STONE study. Contemp Clin Trials 46:106–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2015.12.005

Harrigan M, Cartmel B, Loftfield E, Sanft T, Chagpar AB, Zhou Y et al (2016) Randomized trial comparing telephone versus in-person weight loss counseling on body composition and circulating biomarkers in women treated for breast cancer: the lifestyle, exercise, and nutrition (LEAN) study. J Clin Oncol 34(7):669–676. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2015.61.6375

Stolley M, Sheean P, Gerber B, Arroyo C, Schiffer L, Banerjee A et al (2017) Efficacy of a weight loss intervention for African American breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 35(24):2820–2828. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.71.9856

Santa-Maria CA, Coughlin JW, Sharma D, Armanios M, Blachford AL, Schreyer C et al (2020) The effects of a remote-based weight loss program on adipocytokines, metabolic markers, and telomere length in breast cancer survivors: the POWER-remote trial. Clin Cancer Res 26:3024–3034. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-19-2935

Reeves M, Winkler E, Mccarthy N, Lawler S, Terranova C, Hayes S et al (2017) The living well after breast cancer™ pilot trial: a weight loss intervention for women following treatment for breast cancer. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol 13:125–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajco.12629

Schmitz KH, Troxel AB, Dean LT, DeMichele A, Brown JC, Sturgeon K et al (2019) Effect of home-based exercise and weight loss programs on breast cancer-related lymphedema outcomes among overweight breast cancer survivors: the WISER survivor randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 5(11):1605–1613. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2109

Goodwin PJ, Segal RJ, Vallis M, Ligibel JA, Pond GR, Robidoux A et al (2014) Randomized trial of a telephone-based weight loss intervention in postmenopausal women with breast cancer receiving letrozole: the LISA trial. J Clin Oncol 32(21):2231–2239. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2013.53.1517

Reeves MM, Terranova CO, Erickson J, Job JR, Brookes DS, McCarthy N et al (2016) Living well after breast cancer randomized controlled trial protocol: evaluating a telephone-delivered weight loss intervention versus usual care in women following treatment for breast cancer. BMC Cancer 16:830. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2858-0

Rock CL, Byers TE, Colditz GA, Demark-Wahnefried W, Ganz PA, Wolin KY et al (2013) Reducing breast cancer recurrence with weight loss, a vanguard trial: the exercise and nutrition to enhance recovery and good health for you (ENERGY) trial. Contemp Clin Trials 34(2):282–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2012.12.003

Stolley MR, Sharp LK, Fantuzzi G, Arroyo C, Sheean P, Schiffer L et al (2015) Study design and protocol for moving forward: a weight loss intervention trial for African-American breast cancer survivors. BMC Cancer 15:1018. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-2004-4

Winkels RM, Sturgeon KM, Kallan MJ, Dean LT, Zhang Z, Evangelisti M et al (2017) The women in steady exercise research (WISER) survivor trial: the innovative transdisciplinary design of a randomized controlled trial of exercise and weight-loss interventions among breast cancer survivors with lymphedema. Contemp Clin Trials 61:63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2017.07.017

Appel L, Clark J, Yeh H, Wang N, Coughlin J, Daumit G et al (2011) Comparative effectiveness of weight-loss interventions in clinical practice. N Engl J Med 365:1959–1968. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1108660

Pakiz B, Flatt SW, Bardwell WA, Rock CL, Mills PJ (2011) Effects of a weight loss intervention on body mass, fitness, and inflammatory biomarkers in overweight or obese breast cancer survivors. Int J Behav Med 18(4):333–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-010-9079-8

Tometich DB, Mosher CE, Winger JG, Badr HJ, Snyder DC, Sloane RJ et al (2017) Effects of diet and exercise on weight-related outcomes for breast cancer survivors and their adult daughters: an analysis of the DAMES trial. Support Care Cancer 25(8):2559–2568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3665-0

Wadden TA, Volger S, Sarwer DB, Vetter ML, Tsai AG, Berkowitz RI et al (2011) A two-year randomized trial of obesity treatment in primary care practice. N Engl J Med 365(21):1969–1979. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1109220

Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Donato KA et al (2014) Guidelines (2013) for managing overweight and obesity in adults. Obesity 22:S1–S410. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee

Chlebowski RT, Reeves MM (2016) Weight loss randomized intervention trials in female cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 34(35):4238–4248. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2016.69.4026

Goode AD, Lawler SP, Brakenridge CL, Reeves MM, Eakin EG (2015) Telephone, print, and Web-based interventions for physical activity, diet, and weight control among cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 9(4):660–682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0442-2

Hoedjes M, van Stralen MM, Joe STA, Rookus M, van Leeuwen F, Michie S, Seidell JC, Kampman E (2017) Toward the optimal strategy for sustained weight loss in overweight cancer survivors: a systematic review of the literature. J Cancer Surviv. 11(3):360–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0594-8

Williamson DA, Bray GA, Ryan DH (2015) Is 5% weight loss a satisfactory criterion to define clinically significant weight loss? Obesity (Silver Spring) 23(12):2319–2320. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21358

Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Meyerhardt J, Courneya KS, Schwartz AL et al (2012) Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin 62(4):243–274. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21142

Robien K, Demark-Wahnefried W, Rock CL (2011) Evidence-based nutrition guidelines for cancer survivors: current guidelines, knowledge gaps, and future research directions. J Am Diet Assoc 111(3):368–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2010.11.014

Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, Henry KS, Mackey HT, Cowens-Alvarado RL et al (2016) American cancer society/American society of clinical oncology breast cancer survivorship care guideline. J Clin Oncol 34(6):611–635. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21319

Ricci-Cabello I, Vasquez-Mejia A, Canelo-Aybar C, de Guzman EN, Perez-Bracchiglione J, Rabassa M et al (2020) Adherence to breast cancer guidelines is associated with better survival outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies in EU countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 20(1):920. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05753-x

Jia T, Liu Y, Fan Y, Wang L, Jiang E (2022) Association of healthy diet and physical activity with breast cancer: lifestyle interventions and oncology education. Front. Public Health. 10:797794. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.797794

Hoedjes M, Nijman I, Hinnen C (2022) Psychosocial determinants of lifestyle change after a cancer diagnosis: a systematic review of the literature. Cancers (Basel) 14(8):2026. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14082026

Epton T, Keyworth C, Goldthorpe J, Calam R, Armitage CJ (2022) Are interventions delivered by healthcare professionals effective for weight management? A systematic review of systematic reviews. Public Health Nutr 25(4):1071–1083. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021004481

Johnson BT, Hennessy EA (2019) Systematic reviews and meta-analyses in the health sciences: best Practice methods for research syntheses. Soc Sci Med 233:237–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.035

Acknowledgments

The publication of the article in OA mode was financially supported by HEAL-Link.

Funding

Open access funding provided by HEAL-Link Greece. The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MP and OA conceived the review and formulated the research question. MP, OA and IH developed the search strategy. MP and DS conducted the searches and the screening, independently. MP, DS and CC conducted the data extraction. MP conducted the original draft preparation with input from OA, IH, CC, DS, YT, ES and OA supervised the study. All authors provided critical input for important intellectual content, reviewed the manuscript and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

IARC disclaimer

Where authors are identified as personnel of the International Agency for Research on Cancer / World Health Organization, the authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy or views of the International Agency for Research on Cancer/World Health Organization.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Perperidi, M., Saliari, D., Christakis, C. et al. Identifying the effective behaviour change techniques in nutrition and physical activity interventions for the treatment of overweight/obesity in post-treatment breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Cancer Causes Control 34, 683–703 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-023-01707-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-023-01707-w