Abstract

Background

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination rates among adolescents are increasing in Minnesota (MN) but remain below the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% completion of the series. The goal of this study was to identify messaging and interventions impacting HPV vaccine uptake in MN through interviews with clinicians and key stakeholders.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured key participant interviews with providers and stakeholders involved in HPV vaccination efforts in MN between 2018 and 2019. Provider interview questions focused on messaging around the HPV vaccine and clinic-based strategies to impact HPV vaccine uptake. Stakeholder interview questions focused on barriers and facilitators at the organizational or state level, as well as initiatives and collaborations to increase HPV vaccination. Responses to interviews were recorded and transcribed. Thematic content analysis was used to identify themes from interviews.

Results

14 clinicians and 13 stakeholders were interviewed. Identified themes were grouped into 2 major categories that dealt with messaging around the HPV vaccine, direct patient–clinician interactions and external messaging, and a third thematic category involving healthcare system-related factors and interventions. The messaging strategy identified as most useful was promoting the HPV vaccine for cancer prevention. The need for stakeholders to prioritize HPV vaccination uptake was identified as a key factor to increasing HPV vaccination rates. Multiple providers and stakeholders identified misinformation spread through social media as a barrier to HPV vaccine uptake.

Conclusion

Emphasizing the HPV vaccine’s cancer prevention benefits and prioritizing it among healthcare stakeholders were the most consistently cited strategies for promoting HPV vaccine uptake. Methods to combat the negative influence of misinformation about HPV vaccines in social media are an urgent priority.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The HPV vaccine is recommended for administration to all adolescents in the USA for the prevention of HPV-related cancers and anogenital warts [1]. Uptake of the HPV vaccine in the USA has been lower than that of other adolescent vaccines and remains below the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% completion of the vaccine series [2]. HPV vaccine uptake rates also vary regionally and by state. In Minnesota, data from the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) indicate that the rate of uptake of the HPV vaccine among adolescents aged 13 to 17 in 2018 was 76.7% for one dose and 58.1% for completion of the series [3]. While these uptake rates compared favorably to the USA as a whole (68.1% for receipt of at least one dose and 51.1% for completion of the series), they remain below the Healthy People 2020 goal [3].

Clinician recommendations influence parents’ opinion of their adolescents’ receipt of the HPV vaccine [4, 5]. Multiple studies have linked a clinician’s recommendation to vaccinate adolescents for HPV to greater willingness to follow through with vaccination. Clinicians play an important role in ensuring that adolescents receive the HPV vaccine [4, 5]. Given their importance in discussing the HPV vaccine with adolescents and their parents, prior efforts have been made to assess clinicians’ opinions about prioritizing HPV vaccine delivery, structuring care teams to optimize vaccination efforts, and addressing barriers to vaccination [6]. There are also ongoing efforts to evaluate educational interventions targeted at clinicians to promote HPV vaccination [7]. Key stakeholders involved in HPV vaccination, such as those responsible for quality improvement initiatives at health maintenance organizations or affiliated with local and state health departments, can also play a role in supporting HPV vaccination.

In order to better understand what methods to employ to improve HPV vaccine uptake, we aimed to first understand what messages were perceived by clinicians and healthcare stakeholders that were thought to impact uptake of the HPV vaccine. Additionally, we aimed to gather further knowledge of best practices and innovative strategies being used to promote HPV vaccine uptake that would provide information to design future interventions. We performed a thematic content analysis of interviews conducted with practicing clinicians and HPV-focused stakeholders in Minnesota to address these aims.

Materials and methods

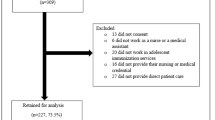

We conducted semi-structured key participant interviews with 14 clinicians and 13 key stakeholders in Minnesota regarding HPV vaccination. The interviews took place from July 2018 to August 2019. Clinicians were interviewed by an infectious disease fellow physician and PhD student in epidemiology. Stakeholder interviews were conducted by an Epidemiology PhD and the project’s principal investigator as well as a PhD student in epidemiology. We asked about effective messaging strategies, quality improvement initiatives, and support for HPV vaccine-related legislation in Minnesota. This research was considered exempt by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Key informant interviews were structured according to a guide comprised of questions asked of each clinician or stakeholder. Clinician and stakeholder interview questions were developed by a team consisting of an epidemiologist with experience involving development of HPV screening guidelines, other epidemiologists with experience conducting content analysis, and a practicing infectious disease fellow physician. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by study personnel.

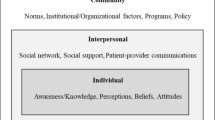

Thematic content analysis was used to analyze the data. The framework for content analysis was to identify key phrases involving messaging around the HPV vaccine and strategies to improve uptake among clinicians and healthcare-related stakeholders. Prior to conducting interviews, the coding scheme for clinician interviews was developed by an infectious disease fellow physician and MPH student based around pre-determined interview questions. The coding scheme for stakeholder interviews was developed by the project’s principal investigator.

The content of the transcribed interviews was independently reviewed by two researchers. Each reviewer first independently read through the entire text of each transcribed interview once and identified key words or phrases associated with barriers or facilitators to HPV vaccination. Subsequently, the key words and phrases that were identified were compared between the two researchers via a second read-through of each interview with patterns among the coded words used to identify specific themes. Identified themes were reviewed in research team sessions to further refine them and lessen the risk of individual reader bias.

Clinicians

A target sample size of fifteen individuals was set prior to clinician recruitment. Clinicians were included if they were physicians or nurse practitioners currently working in an ambulatory clinic in Minnesota and were involved in discussions about the HPV vaccine with their patients. Additionally, only clinicians who were able to order and prescribe the HPV vaccine were eligible to participate. Retired clinicians and those not actively engaged in an ambulatory primary care practice were excluded. Affiliates at the Minnesota chapter of the American Cancer Society and the Minnesota Department of Health aided in identifying clinicians for this study through purposive sampling. Outreach to clinicians occurred via e-mail contact by a research assistant. Potential participants were e-mailed the interview questions and a consent form prior to the interview. Consent to participate was confirmed via an e-mail reply message or verbally prior to the start of the interview.

Participants were asked a series of open-ended questions related to their communication about the HPV vaccine as shown in Table 1. Topics that were addressed included concerns related to receipt of the HPV vaccine, differences in messaging strategies used for different sexes and population subgroups, and quality improvement projects aimed at increasing uptake of the HPV vaccine within each clinician’s specific healthcare setting.

Stakeholders

We also interviewed thirteen key healthcare stakeholders operating in Minnesota who were identified via purposive sampling. Identification of stakeholders was achieved with the assistance of the Minnesota Health Department and the Minnesota Chapter of the American Cancer Society. Outreach to stakeholders occurred in the same manner as was done with clinicians.

Participants were asked a series of open-ended questions adapted from a previously published survey (Table 2) [8]. Questions were asked about facilitators for and barriers to receipt of HPV vaccination in Minnesota, perceptions about HPV vaccination at the organizational level, and HPV vaccination collaborations with stakeholders from across the state. Stakeholders were also asked about possible next steps for legislation to help improve HPV vaccine uptake rates statewide.

Results

A total of 27 semi-structured interviews were completed with 14 clinicians and 13 stakeholders. Upon completion of content analysis, we identified three larger thematic categories addressing messaging and interventions impacting HPV vaccine uptake. These three thematic categories included messaging pertaining to patient–clinician interactions around the HPV vaccine (Table 3), concerns around external messaging sources not involving direct patient–clinician interactions (Table 4), and interventions related to healthcare system-related factors (Table 5).

Patient–clinician interactions

Concerns regarding parental perceptions about the connection between the HPV vaccine and sexual activity featured commonly in both clinician and stakeholder interviews. Messaging around the impact of the HPV vaccine on sexual activity was the most frequently identified theme (for clinicians n = 11, for stakeholders n = 6). Interviewees often cited how parents would raise concerns that receipt of the HPV vaccine could result in early initiation of sexual activity and more frequent sexual encounters among adolescents. As one clinician expressed, “the parents have to [give] written consent in order to administer [the] HPV vaccine. And I would say the most common concern is about sexually transmitted virus [sic]. That’s why parents refuse it…” (Clinician 7). One stakeholder noted that “in my opinion, some of it is perception about, you know, you only need the vaccine if you are sexually active, and you are going to encourage sexually active behavior if you give your kid the HPV vaccine” (Stakeholder 2). Concerns that the age at which the vaccine was recommended was too young were noted by some clinicians and were related to concerns about addressing adolescent sexual activity— “Addressing the fact that you are offering a vaccine prior to sexual activity to young people starting at the age of eleven. That often takes parents aback quite a bit” (Clinician 9).

Clinicians often also described fielding concerns from parents of adolescent patients about the safety of the HPV vaccine. Safety issues primarily came up around the idea that the vaccine may cause adverse side effects with one clinician noting “I get a lot of questions about side effects, ‘I’ve heard bad things’ or ‘I’ve heard that a child has fainted’ or something like that” (Clinician 3).

Influence of external messaging

Discussing vaccines in the context of cancer prevention was commonly cited as a messaging tool for promotion of the HPV vaccine (Table 4). Clinicians expressed how a focus on the benefits of cancer prevention from the HPV vaccine could turn the focus of patients’ parents away from concerns about sexual activity. “I think the concern about cancer and transmission rings home” (Clinician 7). This was the most utilized method of messaging strategy among all clinicians interviewed (n = 11) and a primary health outcome of HPV vaccination programs identified by stakeholders (n = 13).

Concerns surrounding misinformation being spread on social media were also very common. Clinicians described encounters with parents who found misinformation online and how challenging they found addressing misinformation about the vaccine could be. One clinician noted that misinformation derived from the internet could raise “emotional kinds of concerns that are really hyped up … It’s pretty intense. If you bought into it, you’d but into it hook, line, and sinker. It’s got a lot of fear-based drive to it” (Clinician 10). Stakeholders shared in this frustration but highlighted that some media campaigns to raise awareness have had positive results. As one stakeholder noted, “one way to engage in this information sharing is through social media usage, with newspaper articles, mainstream media, and credible news sources to leverage this information and make vaccination the norm” (Stakeholder 9).

Bringing in outside experiences during clinician–patient interactions was frequently noted as a method to help normalize the HPV vaccine and its benefits and counter misinformation derived from other sources. Some providers shared their positive personal experiences with the vaccine as one clinician noted that “I typically share that my children have gotten or will get it and that it’s our only vaccine that prevents cancer” (Clinician 10). Most clinicians noted the impact of making a strong recommendation to get the HPV vaccine as a priority to increase its uptake. As one clinician stated, “I think having a conversation with the families to make sure they understand why we’re doing it and the importance of it—the clinician-to-family conversation. We also present it as part of the recommended immunization series, but to use, it’s the same … It’s an important vaccine that we highly recommend” (Clinician 8).

Healthcare system-related factors

Stakeholders were asked about HPV vaccination at the organizational level. For most organizations, HPV vaccination had become more of a priority recently. However, it was often in competition with other organizational commitments: “Well, if I could say on a scale of 1 to 10, it’s not a 0 and it’s not a 10 … maybe an 8 because it is publicly reported” (Stakeholder 2).

Less than half of the clinicians we interviewed knew of ongoing quality improvement initiatives to increase HPV vaccine uptake within their organizations. Clinicians who noted quality improvement initiatives frequently cited local access expansion and clinic workflow measures as targets for increasing HPV vaccine uptake. Expanding access to the vaccine by offering it at venues outside the clinic was one commonly cited measure with a clinician noting “We also have started offering the HPV vaccine in our express clinics. We have two express clinics in the community where … they’re located at supermarkets” (Clinician 5). Changes addressing vaccines during the check-in process and leveraging the electronic medical record (EMR) system were also commonly employed to try to increase HPV vaccine uptake. One example of this was a clinician who noted that checking for vaccine receipt occurred at the time of any visit even outside of usual annual physicals—“If they’re in for any other visit outside of a yearly physical, then the rooming process includes checking the vaccine status for anybody even if it’s not for their annual visit …” (Clinician 10).

Partnerships precipitated by stakeholder groups with clinicians were felt to be crucial at improving HPV vaccine uptake. One stakeholder noted that “we have completed two rounds of a quality improvement initiative working with physicians not only in Minnesota but also in a five-state area to improve administration of first-dose HPV before age 13 for both boys and girls in their practice. We’ve seen those rates increase from 30 up to 70% as part of the second round of the quality improvement that we have done” (Stakeholder 6). For organizations in which stakeholders described an ongoing quality improvement initiative, the use of financial incentives for patients who have received the HPV vaccine was considered to result in high rates of success. One stakeholder noted that “we have member incentives in the form of [gift cards] that we are giving out to members when they get their full series of HPV vaccination” (Stakeholder 8).

Discussion

Our study identified themes around messaging and interventions involving HPV vaccine uptake commonly encountered by clinicians and healthcare-related stakeholders practicing in Minnesota. The most commonly encountered concern raised by adolescents’ parents about the HPV vaccine during clinic visits involved its impact on sexual activity. The messaging strategy most consistently recommended among interviewees was the promotion of the HPV vaccine as a cancer prevention vaccine. Several clinicians in our study described the benefit of framing the vaccine solely in terms of its cancer prevention benefit. This insight is prescient given that efforts in other states to evaluate barriers to HPV vaccine uptake have shown that a lack of understanding about the link between cancer and the HPV vaccine is common among parents of adolescents [9, 10]. The lack of prioritization of the HPV vaccine among healthcare systems and other stakeholders within Minnesota was another important finding from this study as many clinicians noted that they were not involved with any direct quality improvement projects focused on raising HPV vaccine uptake rates in their clinics. However, there seemed to be increasing awareness of the importance of HPV vaccine administration, particularly as measures are being taken to publicly report this data in Minnesota. Increasing awareness of the benefits of increasing HPV vaccine uptake among healthcare organizations operating within Minnesota would be a good starting point for improving HPV vaccine uptake rates.

Additionally, concerns about misinformation related to the impact of social media were common among both clinician and stakeholder interviewees. Also mentioned were quality improvement initiatives and media campaigns that utilize electronic media to counter misinformation and promote the benefits of the HPV vaccine. There is an emerging literature around the possibility of utilizing social media to better understand concerns related to the HPV vaccine [11]. Some studies have analyzed how the content of messages posted on social media platforms drive varying levels of engagement and the routes through which they link to sites providing information about the HPV vaccine [11,12,13]. A method to leverage social media platforms to directly reach target populations who would benefit from receipt of the HPV vaccine has also been examined [14]. Specific quality improvement projects that incorporate electronic medical records and other electronic or social media were mentioned by several clinicians and stakeholders as a means to improve HPV vaccine uptake rates. Our study has helped to highlight these for future interventions that could be deployed to improve HPV vaccine uptake rates in Minnesota and elsewhere.

Our sampling strategy for identifying interviewees is a potential limitation of this study given that many of our interviewees were drawn from Minnesota’s largest metropolitan areas, potentially decreasing the viewpoints of residents of more rural parts of the state. However, we worked in conjunction with the Minnesota Department of Health to identify areas of lower vaccine uptake within Minnesota and did specific outreach in those counties of the state found to have HPV vaccine uptake rates that were below the statewide average. An additional limitation of our study was its small number of interviewees, which could reduce the perceived number of factors identified in our study as being significant to a larger group of clinicians or stakeholders (e.g., vaccine perception among specific population subgroups). However, our sampling methods allowed for outreach to interviewees over a broad geographic area within Minnesota, resulting in capture of a diverse breadth of attitudes around HPV vaccination. This can help us to build upon prior studies on this topic in Minnesota that utilized a narrower scope of recruitment [15, 16]. The results will allow for the design of more targeted qualitative and quantitative studies to evaluate factors that may be more pertinent to our state, such as the effect of including HPV vaccination as a community measure.

Conclusion

In conclusion, clinicians and stakeholders working within Minnesota highlighted consistent messages expressed by patients and their family members that were often grounded in a lack of knowledge about the HPV vaccine or misinformation. These factors could contribute to hesitancy to receive the HPV vaccine and account for issues with increasing HPV vaccine uptake to the Healthy People 2020 target of 80% completion of the vaccine series among adolescents.

Messaging methods to counter misinformation were also described as were techniques involving quality improvement projects being implemented in some clinics as previously described. These included providing a strong provider recommendation to receive the HPV vaccine, focusing on cancer prevention benefits of the vaccine, normalizing the vaccine as part of a standard set of immunizations, leveraging clinic workflow and EMR systems, using social media campaigns to promote awareness and factual information about the vaccine, and utilizing novel strategies such as financial incentives to promote vaccine uptake. The information gleaned from this study will be informative for designing clinical interventions at a larger scale to help increase HPV vaccine uptake. While this study was conducted within Minnesota, the lessons learned can be applied more generally to other communities outside the state.

Data availability

Transcribed interviews are maintained electronically at the University of Minnesota and are available for viewing upon request.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Recommended child and adolescent immunization schedule for ages 18 years or younger, United States, 2019. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/imz/child-adolescent.html#note-hpv.

Healthy People 2020 (2014). HPV vaccine, adolescents, 2008–2012. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/national-snapshot/hpv-vaccine-adolescents-2008%E2%80%932012

Minnesota Department of Health. (2019). Adolescent immunization coverage in Minnesota. https://www.health.state.mn.us/people/immunize/stats/adol/coverdata.html

Rosenthal S, Weiss TW, Zimet G, Ma L, Good M, Vichnin M (2011) Predictors of HPV vaccine uptake among women aged 19–26: importance of a physician’s recommendation. Vaccine 29:890–895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.12.063

Kester L, Zimet G, Fortenberry JD, Kahn J, Shew M (2013) A national study of HPV vaccination of adolescent girls: rates, predictors, and reasons for non-vaccination. Maternal Child Health J 17:879–885. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-012-1066-z

Chuang E, Cabrera C, Mak S, Glenn B, Hochman M, Bastani R (2017) Primary care team- and clinic level factors affecting HPV vaccine uptake. Vaccine 35:4540–4547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.028

Rosen BL, Bishop JM, McDonald SL, Kahn JA, Kreps GL (2018) Quality of web-based educational interventions for clinicians on human papillomavirus vaccine: content and usability assessment. JMIR Cancer. https://doi.org/10.2196/cancer.9114

Cartmell KB, Young-Pierce J, McGue S, Alberg AJ, Luque JS, Zubizarreta M, Brandt HM (2018) Barriers, facilitators, and potential strategies for increasing HPV vaccination: a statewide assessment to inform action. Papillomavirus Res 5:21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pvr.2017.11.003

Dilley SE, Peral S, Straugh JM, Scarinci IC (2018) The challenge of HPV vaccination uptake and opportunities for solutions: lessons learned from Alabama. Prev Med 113:124–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.05.021

Mroz S, Zhang X, Williams M, Conlon A, LoConte NK (2017) Working to increase vaccination for human papillomavirus: A survey of Wisconsin stakeholders, 2015. Prev Chronic Dis. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd14.160610

Lama Y., Hu D., Jamison A., Quinn S.C., Broniatowski D.A. (2019). Characterizing trends in human papillomavirus vaccine discourse on Reddit (2007–2015): An observational study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 5(1), Article e12480. https://doi.org/10.13016/8hlj-3xnd

Keim-Malpass J, Mitchell EM, Sun E, Kennedy C (2017) Using Twitter to understand public perceptions regarding the #HPV Vaccine: Opportunities for public health nurses to engage in social marketing. Public Health Nurs 34(4):316–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12318

Massey P.M., Alex Budenz M.A., Leader A., Fisher K., Klassen A., Yom-Tov E. (2018). What drives health professionals to tweet about #HPVvaccine? Identifying strategies for effective communication. Prev Chronic Dis 15, Article 170320. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd15.170320

Mohanty S, Leader AE, Gibeau E, Johnson C (2018) Using Facebook to reach adolescents for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination. Vaccine 36:5955–5961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.08.060

Abakporo U, Hussein A, Begun JW, Shippee T (2018) Knowledge, beliefs and attitudes of somali men in Olmsted County, Minnesota, U.S., on the human papillomavirus vaccine and cervical cancer screening. J Immigr Minor Health 20(5):1230–1235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0642-0

Lambert L (2014) Knowledge of HPV, perception of risk, and intent to obtain HPV vaccination among sampled male university students at Minnesota State University, Mankato. (Publication No. 304) [Master’s thesis, Minnesota State University – Mankato]. Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1303&context=etds

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of collaborators from the Minnesota Department of Health in providing statewide data regarding HPV vaccine uptake in Minnesota and the Minnesota chapter of the American Cancer Society in assisting with identifying interview participants.

Funding

Supported by a Healthcare Delivery Research Program grant from the National Cancer Institute Division of Cancer Control & Population Sciences (NCI 5P30CA077598-19). Dr. Yared was supported by the National Institutes of Health Infectious Disease Training in Clinical Investigation Grant (T32 AI055433-11A1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yared, N., Malone, M., Welo, E. et al. Challenges related to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake in Minnesota: clinician and stakeholder perspectives. Cancer Causes Control 32, 1107–1116 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-021-01459-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-021-01459-5