Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the association between cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and esophageal adenocarcinoma survival, including stratified analysis by selected prognostic biomarkers.

Methods

A population-representative sample of 130 esophageal adenocarcinoma patients (n = 130) treated at the Northern Ireland Cancer Centre between 2004 and 2012. Cox proportional hazards models were applied to evaluate associations between smoking status, alcohol intake, and survival. Secondary analyses investigated these associations across categories of p53, HER2, CD8, and GLUT-1 biomarker expression.

Results

In esophageal adenocarcinoma patients, there was a significantly increased risk of cancer-specific mortality in ever, compared to never, alcohol drinkers in unadjusted (HR 1.96 95% CI 1.13–3.38) but not adjusted (HR 1.70 95% CI 0.95–3.04) analysis. This increased risk of death observed for alcohol consumers was more evident in patients with normal p53 expression, GLUT-1 positive or CD-8 positive tumors. There were no significant associations between survival and smoking status in esophageal adenocarcinoma patients.

Conclusions

In esophageal adenocarcinoma patients, cigarette smoking or alcohol consumption was not associated with a significant difference in survival in comparison with never smokers and never drinkers in fully adjusted analysis. However, in some biomarker-selected subgroups, ever-alcohol consumption was associated with a worsened survival in comparison with never drinkers. Larger studies are needed to investigate these findings, as these lifestyle habits may not only be linked to cancer risk but also cancer survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Esophageal cancer has a rising incidence and is the eighth most common cancer worldwide with 572,034 new diagnosis made in 2018 [1]. Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma continues to be the predominant esophageal cancer; however, in the last three to four decades, there has been a dramatic shift in the demographics of the histological sub-type of esophageal cancer diagnosed. In the developed world, there is a decreased incidence of squamous cell carcinoma, and a simultaneous increase in the incidence of adenocarcinoma [1, 2]. For example, in the USA, between 1975 and 2004, there was a 463% increase in esophageal adenocarcinoma and similar patterns have been seen in the UK, and Western Europe where the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma now outnumbers the incidence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [1, 3]. Esophageal adenocarcinoma 5-year survival rates in the Western world range from 10 to 18% [4, 5] and this is partially due to only 38% of patients being suitable to undergo treatment with a curative intent [6]. However, even within patients with localized disease that undergo attempted curative resection, the 5-year survival is still as low as 47% which highlights the need for additional research in an effort to improve survival rates [7].

The impact of lifestyle factors on esophageal adenocarcinoma development has been investigated extensively. For example, the BEACON consortium demonstrated a strong association between cigarette smoking and esophageal adenocarcinoma development [8], and therefore, it could be hypothesized that cigarette smoking may also impact upon survival in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Although there has been shown to be no association between alcohol consumption and esophageal adenocarcinoma risk [9], it is worthwhile investigating if alcohol consumption plays a role in prognosis as it is an easily modifiable risk factor and is known to have a synergistic effect with cigarette smoking in other cancers. However, only four published studies, including relatively small numbers of patients, have investigated the association between tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, and esophageal adenocarcinoma survival [10,11,12,13]. Our working group has published a recent meta-analysis combining two of these studies, which demonstrated no significant difference in esophageal adenocarcinoma survival in never-alcohol drinkers compared to moderate alcohol drinkers (HR 1.34 95% CI 0.95–1.89) [14]. Similarly, there were no associations with survival in esophageal adenocarcinoma patients who were current (HR 0.99 95% CI 0.73–1.36) or former (HR 0.88 95% CI 0.68–1.14) smokers, compared to never smokers [14]. This meta-analysis also investigated the association between these lifestyle factors and survival in other cancers of the digestive tract. Results demonstrated that cigarette smoking was associated with poorer survival in patients with colorectal, gastric, or pancreatic cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, or esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [14]. Alcohol consumption was associated with a poorer survival in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma or hepatocellular carcinoma [14]. Given the current dearth of research on the association between these lifestyle factors and esophageal adenocarcinoma survival, further studies are necessary.

The primary aim of this study is to investigate the potential association between cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and esophageal adenocarcinoma survival. A secondary aim was to investigate the impact of these lifestyle factors on survival, according to the expression of the selected biomarkers, P53, HER2, GLUT1, and CD8 which have been shown to be associated with prognosis in esophageal adenocarcinoma [15,16,17,18].

A higher expression of P53, HER2, and GLUT1 has individually been shown to be associated with a worse survival in esophageal adenocarcinoma [19]. However, there have been a variety of other cancers which have been investigated with a similar methodology. In esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, heavy smokers have been shown to have a two-times higher odds of P53 mutation than non-smokers [20], and in lung cancer, frequent alcohol drinkers had a 4.6-fold increased odds of having a P53 mutation [21]. Several studies in breast cancer have not shown any association between alcohol consumption and HER2 receptor expression [22] and to date, no studies have reported on the impact of cigarette smoking or alcohol consumption on GLUT1 expression in any type of cancer. A higher CD8+ tumor expression in esophageal adenocarcinoma has been shown to be associated with a significantly improved overall survival [23]. Despite these findings, no previous studies have investigated the impact of smoking or alcohol consumption on esophageal adenocarcinoma survival according to strata of these biomarkers, which is an important consideration for future precision medicine initiatives. This study represents a molecular pathology epidemiology approach, which has not been extensively applied in esophageal cancer survival studies to date [24].

Methods

This study was performed and reported in line with the REMARK guidelines [25].

Patient selection

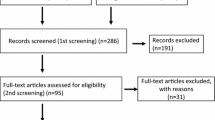

In this population-representative study, all patients in Northern Ireland who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection for esophageal adenocarcinoma between 1 January 2004 and 31 December 2012 were identified. There were 158 corresponding formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) esophageal adenocarcinoma resection specimens collected from the Northern Ireland Cancer Centre. Of these, matched clinical information was available for 137 patients, but seven patients (for the reasons outlined in Fig. 1) were excluded, leaving 130 patients for inclusion in the primary analysis. Relevant ethical approvals were obtained from the Northern Ireland Biobank (NIB12-0032 and NIB12-0062) and the Office for Research Ethics Committees Northern Ireland (ORECNI, 13/NI/0149) [26]. The staining and study of the biomarker CD8 was performed under the accelerator grant from Cancer Research UK (C11512/A20256 to PWH/MS-T).

Clinical data

Clinical data and information on study outcomes up until 31 December 2014 was retrieved via patient note review at the Northern Ireland Cancer Centre, as previously described [17]. Patient information included age at diagnosis, date of diagnosis, date of surgery, and patient sex. Tobacco smoking status was classified as never, current, and former smokers, as recorded within medical notes. Alcohol consumption was classified as never and ever drinkers, as recorded in patient notes. Those patients with an unknown smoking and alcohol status were also analyzed separately to evaluate if they had differential associations between exposures and survival outcomes.

Pathology reports from resection specimens were reviewed for tumor characteristics including tumor location, presence of lymphovascular invasion, circumferential resection margin status, tumor differentiation, and TNM stage. Tumor location was divided into lower third of esophagus (greater than 5 cm proximal to the esophagogastric junction), Siewert 1 (within 1–5 cm above the oesophagogastric junction), Siewert 2 (within 1 cm above and 2 cm below the oesophagogastric junction), and Siewert 3 (2–5 cm below the oesophagogastric junction) [27]. Pathological staging was defined according to International Union Against Cancer (UICC) TNM staging, 7th edition [28]. Finally, the date and cause of death were recorded, where applicable. The survival time was calculated from the day of diagnosis to the date of death.

Construction of tissue microarrays

A FFPE tissue block was selected from each resection specimen and triplicate 1 mm cores of tumor were embedded in a paraffin block using the Beecher Manual Arrayer® to enable tumor samples to be stained and scored.

Immunohistochemistry staining and scoring

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed within the Northern Ireland Molecular Pathology Laboratory at Queen’s University Belfast, following approval by the Northern Ireland Biobank. To enable biomarker expression to be evaluated, slides were scanned on an Aperio AT2 scanner, and viewed as digital images on Xplore (PathXL) and then manually scored. The validated antibodies and techniques used for immunohistochemical staining are presented in Table 1. Detailed scoring methods are described below for the biomarkers investigated (HER2, p53, GLUT1, and CD8), which were all chosen due to previous publications demonstrating their prognostic ability and/or prevalent staining in esophageal adenocarcinoma tumors [15,16,17,18]. Their interaction with lifestyle factors to influence prognosis is not yet known, and this analysis should be regarded as hypothesis-generating.

p53

The p53 staining was performed as previously described [29]. The nuclear staining intensity and percentage of the tumor cell’s nucleus staining positive in sections of TMA cores were assessed by two independent observers and a final agreement on discordant results was made. Scoring was based on intensity (0 = no staining, 1 = weak, 2 = moderate, and 3 = strong staining observed) and the percentage of tumor cells staining positive (0–100%). These two scores were multiplied to give an H-score between 0 and 300. Triplicate scores were taken for each patient and the maximum score was used for statistical analysis. Patients were then divided into tertiles of p53 expression with the cutoffs for the tertiles being < 80, 80 to < 240, and > 240 which was based on the distribution of p53 expression scores for the included patients. For this study, we describe the middle tertile of 80 to < 240 as the normal range of p53 expression.

GLUT1

GLUT1 has been identified as a marker of poor prognosis in esophageal adenocarcinoma but its interaction with lifestyle factors is not known [17]. Staining was scored by three independent observers as previously described [17], with agreement made on discordant results. If any cancer cell membrane or cytoplasm stained positive for GLUT1. the tumor was considered to be GLUT1-positive and patients were enabled division into groups of GLUT1-positive and GLUT1-negative tumors.

HER-2

HER2 expression was evaluated by assessing the degree of expression in the tumor cell population. Staining was scored by three observers in keeping with the accepted method in the UK and USA as follows: HER2 0− negative no staining or membrane staining is < 10% of cancer cells, 1+ negative faint/barely perceptive membrane staining in more than 10% of the cancer cells, 2+ equivocal weak to moderate complete membrane staining in more than 10% of cancer cells or < 30% with strong complete membrane staining, and 3+ is considered positive and involves strong complete membrane staining in more than 30% of cancer cells [30]. Following application of these scoring methods, patients were divided into HER-2-positive and HER-2-negative tumor categories.

CD8

Scoring for CD8 was performed by two independent observers with a final agreement made on discordant results. A semiquantitative scoring system was employed for CD8 characterization based on the intensity of staining within intratumoural tissue. A score of 3 indicates strong CD8 expression, 2 moderate expression, 1 low or weak expression, and 0 absence. Patients were divided into groups of either CD8-positive (1, 2, 3) or CD8-negative tumors.

Statistical analysis

Patient demographics and tumor characteristics according to smoking status and alcohol consumption were compared using chi-squared tests.

Overall survival (death from any cause) and cancer-specific survival (death from oesophageal adenocarcinoma) were evaluated using Cox proportional hazards regression models for unadjusted and adjusted results. The variables included in the adjusted analysis were age at diagnosis, gender, tumor nodal status, circumferential resection margin, tumor differentiation, lymphovascular invasion, and tumor location. In further analyses, alcohol consumption and smoking status were mutually adjusted for each other. Adjustments for tumor T stage did not influence the model, and therefore, it was omitted from final survival analysis.

Hypothesis-generating survival analysis was performed for smoking and alcohol status stratified by categories of tumor biomarker expression. There were different numbers of patients within each biomarker study as not all cores taken from the TMA from each biomarker staining had the presence of tumor . There were 130 TMA cores included for p53, 130 for HER-2, 129 for GLUT-1, and 100 for CD8. In this analysis, patients were divided into never and ever smokers compared to the never, current, and former used in the primary analysis as the latter, due to relatively small sample sizes in these strata. Stata version 14.2 (College Station, TX, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Patient demographics and tumor characteristics

Of the total 130 oesophageal adenocarcinoma patients in this study, 78% were male and 22% were female and the majority of patients were over 60 years old (70%). The majority of tumors were located at the gastro-esophageal junction (84.6%), with Siewert 1 tumors the most common (50.8%), followed by Siewert 2 (25.4%) and Siewert 3 (8.5%).

Table 2 presents the patient demographics and tumor characteristics across categories of smoking and alcohol status. There was no difference by patient sex, tumor site, lymphovascular invasion status, circumferential resection margin status, tumor differentiation, tumor T stage, or surgical nodal status according to categories of smoking and alcohol status. Current and former smokers were more likely to be older than non-smokers (p = 0.02).

Survival analysis

There were 75 patients who died during a maximum of 9 (median 2.5) years of follow-up, with 70 of these patients having a recorded cause of death as esophageal adenocarcinoma and 5 dying due to other causes.

When comparing ever with never-alcohol consumption for overall survival analysis, there was almost a two-fold increased risk of mortality in unadjusted analysis (HR 1.96 95% CI 1.13–3.38) although this was not statistically significant when adjusted analysis was performed (HR 1.70 95% CI 0.95–3.04). In cancer-specific survival analysis, a similar pattern was observed when comparing ever versus never-alcohol drinkers with a worsened survival in unadjusted analysis (HR 1.99 95% CI 1.12–3.55) and adjusted analysis (HR 1.70 95% CI 0.93–3.11). Mutually adjusting for smoking status did not alter the results shown. These results are presented in Table 3.

Regarding smoking status, there was no apparent difference in overall or cancer-specific survival in either current or former smokers compared to never smokers in both unadjusted and adjusted analysis as shown in Table 3. Additional adjustment for alcohol status did not impact on either set of survival analyses.

Stratified survival analysis by biomarker expression

The unadjusted association between alcohol consumption and survival in esophageal adenocarcinoma patients according to tumor biomarker expression categories are presented in Table 4. The previously observed increased risk of death for alcohol consumers was more evident in patients within the normal tertile of p53 expression (HR 11.8 95% CI 1.55–89.7), GLUT-1-positive (HR 2.40 95% CI 1.31–4.41), CD 8-positive (HR 2.77 95% CI 1.26–6.09), and HER 2-positive tumors (HR 7.00 95% CI 0.85–57.6), although the latter did not reach statistical significance.

The association between smoking status and survival in esophageal adenocarcinoma patients according to tumor biomarker expression categories is presented in Table 5. No associations between smoking status and survival in esophageal adenocarcinoma were observed according to high or low expression of p53, or positive/negative status for HER2, GLUT-1, or CD8.

Discussion

In this population-representative study, patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma who consumed alcohol had a poorer survival than never drinkers, although statistical significance became attenuated in fully adjusted analyses. In our hypothesis-generating analysis stratified by biomarker expression levels, patients who were ever-alcohol drinkers and had tumors with positive expression of GLUT1, CD8, or were in the middle tertile of p53 expression had significantly poorer survival. Smoking status was not associated with outcomes in patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma, and these non-significant observations remained in the analyses stratified by selected biomarker expression levels.

To our knowledge, only three studies and one meta-analysis have previously investigated the association between alcohol consumption and survival in esophageal adenocarcinoma [10, 12,13,14]. A contributing factor to this lack of research may be the short life expectancy associated with this disease, meaning it is difficult to study epidemiological factors in relation to survival. Although none of the adjusted results in these studies reached statistical significance, some did demonstrate a non-significant poorer survival in esophageal adenocarcinoma patients who were alcohol drinkers in line with the current study findings [10, 12,13,14]. It should be noted that previous studies included both curative and palliative patients, whereas the current study only included patients undergoing treatment with a curative intent. Therefore, by focusing on the patients with the most favorable prognosis, we maximized the opportunity to see any effect of these lifestyle factors on survival. For example, in a study reported by Thrift et al., 38% of patients were palliative and a difference in survival outcomes between lifestyle groups may be more difficult to identify [12].

The largest study to date was performed in Australia and included 362 patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma [12]. Alcohol consumption was assessed by providing questionnaires which assessed patient consumption between the ages of 0–29, 30–49, and > 50 which was then used to divide patients into groups of average lifetime alcohol consumption of < 1 drink, 1–6, 7–20 ,and greater than 20 drinks per week with one drink considered to be equivalent to 10 g of alcohol. In adjusted analysis, when comparing outcomes in the groups who consumed alcohol regularly to the group who consumed less than 1 drink per week, there was no significant difference in outcomes, although in the group who drank 7–20 drinks per week, there was a trend of worse survival (HR 1.52 95% CI 0.98–2.37) [12].

The second largest study was carried out by Trivers et al. who performed a multicentered population-based case–control study in the USA with 293 cases of esophageal adenocarcinoma of various stages. In their unadjusted analysis, there was no significant difference in survival between never drinkers and ever drinkers (HR 1.08 95% CI 0.81–1.44) [10]. The third study, a nationwide case–control study performed by Sundelof et al. in Sweden [13] included 177 patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma of which 102 underwent esophagectomy and 75 did not. Alcohol intake was based on consumption 20 years prior to the questionnaire and was divided into never, 1–15 g per week, 16–70 g per week, and more than 70 g per week. There was no difference in survival in any of the alcohol drinker groups compared to the never group [13].

The studies by Thrift et al. and Sundelof et al. were able to be combined in a previous meta-analysis, and although results did not reach a level of statistical significance, they suggested that survival may be worse for moderate drinkers compared to never drinkers (HR 1.34 95% CI 0.95–1.89) [14]. However, there was a lack of dose–response association observed, since weaker survival estimates were reported when heavy alcohol consumption was compared to never consumption (HR 1.01 95% CI 0.70–1.47) [14]. Unfortunately, we were unable to assess dose–response associations for alcohol and smoking, due to the lack of reporting this level of detail in the hospital case notes, which were retrospectively reviewed. Although alcohol is not associated with the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma [9], these results suggest that there is an association with survival and highlights the necessity of larger studies to investigate these findings further in order to inform potential adjuvant lifestyle interventions.

A limited number of studies have investigated the association between tobacco smoking and survival in patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma, and their results are in agreement with our findings [10,11,12,13]. In a meta-analysis by McMenamin et al., these studies were combined and there was no significant difference in survival outcomes when comparing current (HR 0.99 95% CI 0.73–1.36) or former (HR 0.88 95% CI 0.68–1.14) smokers with never smokers, respectively [14]. Our hypothesis-generating results exploring the association between tobacco smoking and survival in esophageal adenocarcinoma patients according to the expression of selected biomarkers also did not reveal significant associations.

The hypothesis-generating results within the alcohol status categories were more interesting and highlight the necessity of further research in this area. To date, there has only been one study (performed on the same cohort of patients as this study) which has investigated the role of GLUT1 as a biomarker in esophageal adenocarcinoma, and positive expression was associated with a poorer prognosis [17]. This is, however, the first study to identify a potential interaction between alcohol, GLUT1 expression, and survival in esophageal adenocarcinoma. The poorer outcomes in ever drinkers with CD8 positive, or normal p53, tumor expression indicate that further mechanistic studies are warranted to verify the biological plausibility of a potential underlying interaction with alcohol intake in relation to prognosis.

This study has several strengths. It adds to the small pool of studies that have been performed in this area and compliments their findings. Furthermore, it is the first study to apply molecular epidemiology pathology methods to study the interaction between lifestyle factors, biomarker expression, and survival. This study has a number of limitations. Firstly, the collected data did not include details on patient comorbidities and therefore adjustments were not made for these in the survival analysis. Secondly, this study has a relatively small sample size, particularly for stratified analyses by biomarker expression, although our cohort size of 130 patients is typical of this relatively rare disease site. Nevertheless, our study provides support for future larger studies to be conducted. Thirdly, all patients in this study had surgically resectable disease, meaning this cohort represents patients with more favorable prognosis, and we cannot deduce if smoking or alcohol consumption impacts upon the outcome in patients with more advanced disease.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that ever-alcohol consumption may have a negative impact on survival in patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma and in particular those patients with CD8- or GLUT1-positive tumors, or with expression of p53 within the middle tertile. However, cigarette smoking was not shown to be associated with survival in patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma. Larger studies are needed to confirm these findings as lifestyle advice could potentially be promoted not just on the basis of decreasing the risk of developing cancer or other medical diagnoses but also for improving outcomes should a patient receive an esophageal adenocarcinoma diagnosis. Studies are also required to investigate the impact of lifestyle change such as cigarette smoking and alcohol cessation at the time of a cancer diagnosis as lifestyle advice could form patients part of a patient’s treatment strategy.

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68:394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492

Arnold M, Soerjomataram I, Ferlay J, Forman D (2015) Global incidence of oesophageal cancer by histological subtype in 2012. Gut 64:381–387. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308124

Pennathur A, Gibson MK, Jobe BA, Luketich JD (2013) Oesophageal carcinoma. Lancet 381(9864):400–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60643-6

Oesophageal cancer survival statistics | Cancer Research UK (2014) Available from https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/oesophageal-cancer/survival

Van Hagen P, Hulshof MCCM, van Lanschot JJB, Steyerberg EW, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BPL, Richel DJ, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, Hospers GAP, Bonenkamp JJ, Cuesta MA, Blaisse RJB, Busch ORC et al (2012) Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1112088

Varagnuam M, Park MH, Sinha S, Cromwell D, Maynard N, Crosby T, Trudgill N, Michalowski J, Salvador A, Napper R (2018) National Oesophago-Gastric Cancer Audit 2018, p 52

Shapiro J, van Lanschot JJB, Hulshof MCCM, van Hagen P, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BPL, van Laarhoven HWM, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, Hospers GAP, Bonenkamp JJ, Cuesta MA, Blaisse RJB, Busch ORC et al (2015) Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for oesophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS): long-term results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 16:1090–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00040-6

Cook MB, Kamangar F, Whiteman DC, Freedman ND, Gammon MD, Bernstein L, Brown LM, Risch HA, Ye W, Sharp L, Pandeya N, Webb PM, Wu AH et al (2010) Cigarette smoking and adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: a pooled analysis from the international BEACON consortium. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 102:1344–1353. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq289

Freedman ND, Murray LJ, Kamangar F, Abnet CC, Michael B, Nyrén O, Ye W, Wu AH, Bernstein L, Brown LM, Mary H (2012) Alcohol intake and risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma: a pooled analysis from the BEACON Consortium. Gut. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2010.233866

Trivers KF, De Roos AJ, Gammon MD, Vaughan TL, Risch HA, Olshan AF, Schoenberg JB, Mayne ST, Dubrow R, Stanford JL, Abrahamson P, Rotterdam H, West AB et al (2005) Demographic and lifestyle predictors of survival in patients with esophageal or gastric cancers. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 3:225–230

Spreafico A, Coate L, Zhai R, Xu W, Chen Z-F, Chen Z, Patel D, Tse B, Brown MC, Heist RS, Dodbiba L, Teichman J, Kulke M et al (2017) Early adulthood body mass index, cumulative smoking, and esophageal adenocarcinoma survival. Cancer Epidemiol 47:28–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2016.11.009

Thrift AP, Nagle CM, Fahey PP, Smithers BM, Watson DI, Whiteman DC (2012) Predictors of survival among patients diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction. Cancer Causes Control 23:555–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-012-9913-1

Sundelöf M, Lagergren J, Ye W (2008) Patient demographics and lifestyle factors influencing long-term survival of oesophageal cancer and gastric cardia cancer in a nationwide study in Sweden. Eur J Cancer 44:1566–1571

McMenamin ÚC, McCain S, Kunzmann AT (2017) Do smoking and alcohol behaviours influence GI cancer survival? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2017.09.015

Gowryshankar A, Nagaraja V, Eslick GD (2014) HER2 status in Barrett’s esophagus & esophageal cancer: a meta analysis. Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2013.039

Fléjou J-F, Muzeau F, Potet F, Lepelletier F, Fékété F, Hénin D (1994) Over expression of the p53 tumor suppressor gene product in esophageal and gastric carcinomas. Pathol—Res Pract 190:1141–1148. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0344-0338(11)80440-1

Blayney JK, Cairns L, Li G, McCabe N, Stevenson L, Peters CJ, Reid NB, Spence VJ, Chisambo C, McManus D, James J, McQuaid S, Craig S et al (2018) Glucose transporter 1 expression as a marker of prognosis in oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.24906

Thomas GJ, Primrose JN, Mellows T, McCormick Matthews LH, Bailey IS, Byrne JP, Bateman AC, Sahota SS, Bateman AR, Ottensmeier CH, Harris S, Noble F, Underwood TJ, et al (2016) Tumour infiltrating lymphocytes correlate with improved survival in patients with oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-016-1826-5

McCormick Matthews LH, Noble F, Tod J, Jaynes E, Harris S, Primrose JN, Ottensmeier C, Thomas GJ, Underwood TJ (2015) Systematic review and meta-analysis of immunohistochemical prognostic biomarkers in resected oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer 113:107–118. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.179

Wu XC, Zheng YF, Tang M, Li XF, Zeng R, Zhang JR (2015) Association between smoking and p53 mutation in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Clin Oncol 27:337–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2015.02.007

Ahrendt SA, Chow JT, Yang SC, Wu L, Zhang M, Jen J, Sidransky D (2000) Alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking increase the frequency of p53 mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer 60:3155–3159

Hirko KA, Chen WY, Willett WC, Rosner BA, Hankinson SE, Beck AH, Tamimi RM, Eliassen AH (2016) Alcohol consumption and risk of breast cancer by molecular subtype: Prospective analysis of the nurses’ health study after 26 years of follow-up. Int J Cancer 138:1094–1101. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29861

Zheng X, Song X, Shao Y, Xu B, Hu W, Zhou Q, Chen L, Zhang D, Wu C, Jiang J (2018) Prognostic role of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in esophagus cancer: a meta-analysis. Cell Physiol Biochem 45:720–732. https://doi.org/10.1159/000487164

Hamada T, Keum NN, Nishihara R, Ogino S (2017) Molecular pathological epidemiology: new developing frontiers of big data science to study etiologies and pathogenesis. J Gastroenterol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-016-1272-3

Altman DGDDG, McShane LLM, Sauerbrei W, Taube SSE, Gion M, Clark G et al (2012) Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK): explanation and elaboration. BMC Med. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-10-51

Lewis C, McQuaid S, Clark P, Murray P, McGuigan T, Greene C, Coulter B, Mills K, James J (2018) The Northern Ireland Biobank: a cancer focused repository of science. Open J Bioresour. https://doi.org/10.5334/ojb.47

Curtis NJ, Noble F, Bailey IS, Kelly JJ, Byrne JP, Underwood TJ (2014) The relevance of the Siewert classification in the era of multimodal therapy for adenocarcinoma of the gastro-oesophageal junction. J Surg Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.23484

Rice TW, Blackstone EH (2013) Esophageal cancer staging. Thorac Surg Clin. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thorsurg.2013.07.004

Boyle DP, Mcart DG, Irwin G, Wilhelm-Benartzi CS, Lioe TF, Sebastian E, Mcquaid S, Hamilton PW, James JA, Mullan PB, Catherwood MA, Harkin DP, Salto-Tellez M (2014) The prognostic significance of the aberrant extremes of p53 immunophenotypes in breast cancer. Histopathology. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.12398

Walker RA, Bartlett JMS, Dowsett M, Ellis IO, Hanby AM, Jasani B, Miller K, Pinder SE (2008) HER2 testing in the UK: Further update to recommendations. J Clin Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2007.054866

Acknowledgments

The samples used in this research were received from the Northern Ireland Biobank which has received funds from HSC Research and Development Division of the Public Health Agency in Northern Ireland and the Friends of the Cancer Centre. Funding for tumor staining for CD8 was obtained from Cancer Research UK as part of the accelerator programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Northern Ireland Biobank (NIB12-0032 & NIB12-0062) and the Office for Research Ethics Committees Northern Ireland (ORECNI, 13/NI/0149)) and within the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

McCain, R.S., McManus, D.T., McQuaid, S. et al. Alcohol intake, tobacco smoking, and esophageal adenocarcinoma survival: a molecular pathology epidemiology cohort study. Cancer Causes Control 31, 1–11 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-019-01247-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-019-01247-2